Training Foundation Models on a Full-Stack AMD Platform: Compute, Networking, and System Design (2511.17127v1)

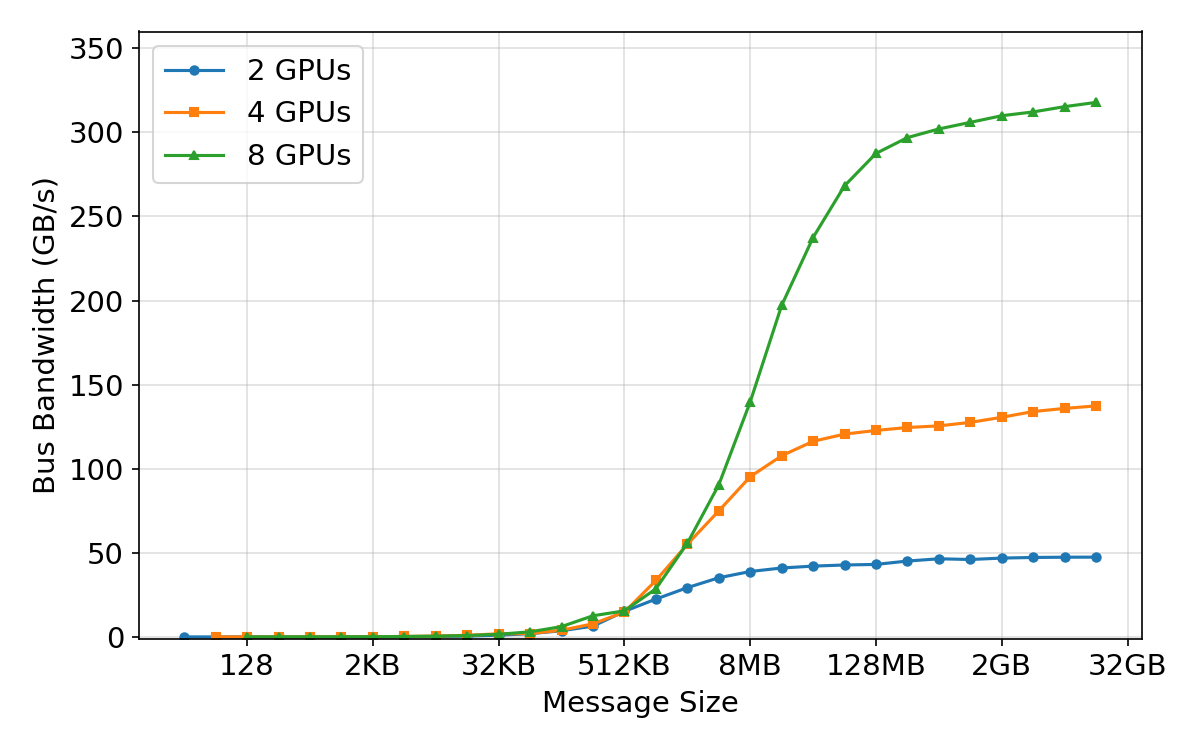

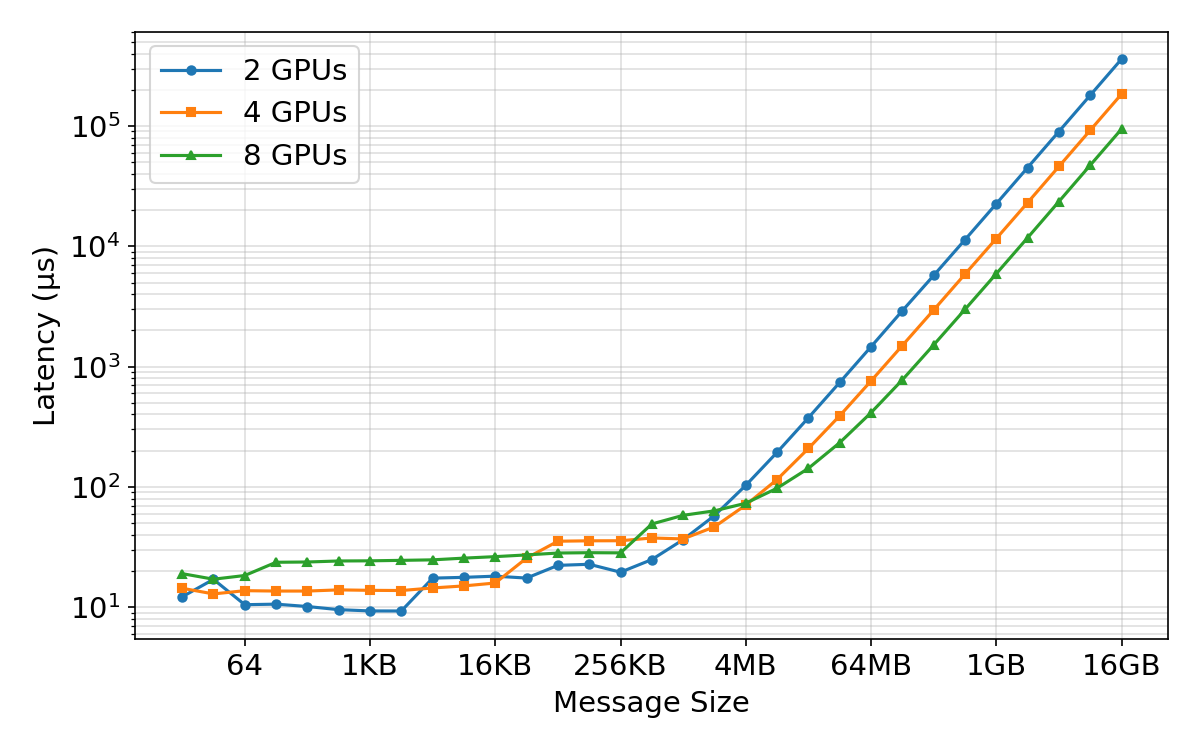

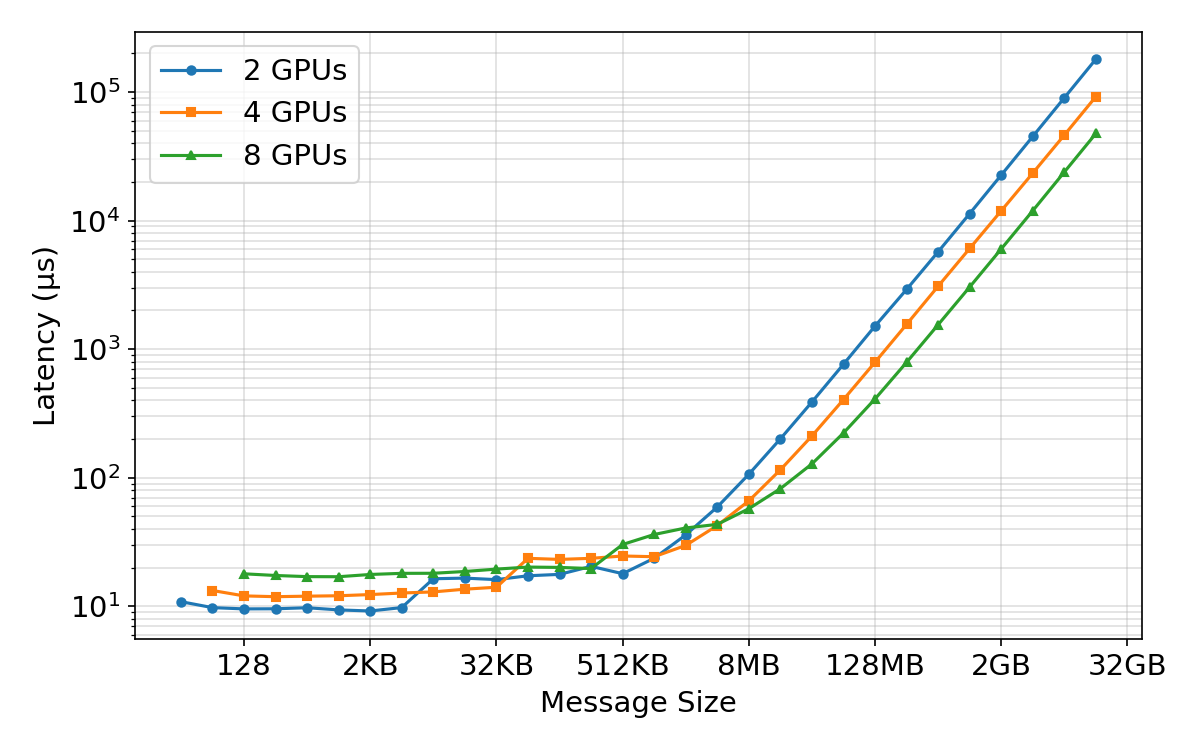

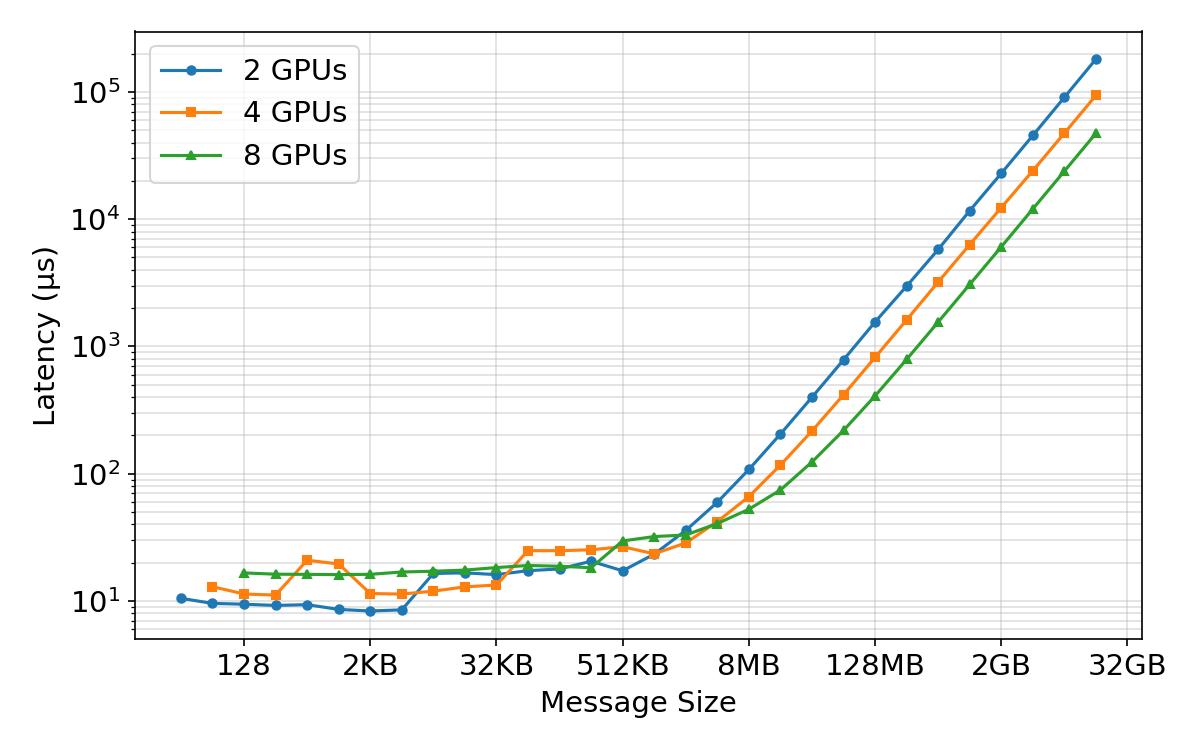

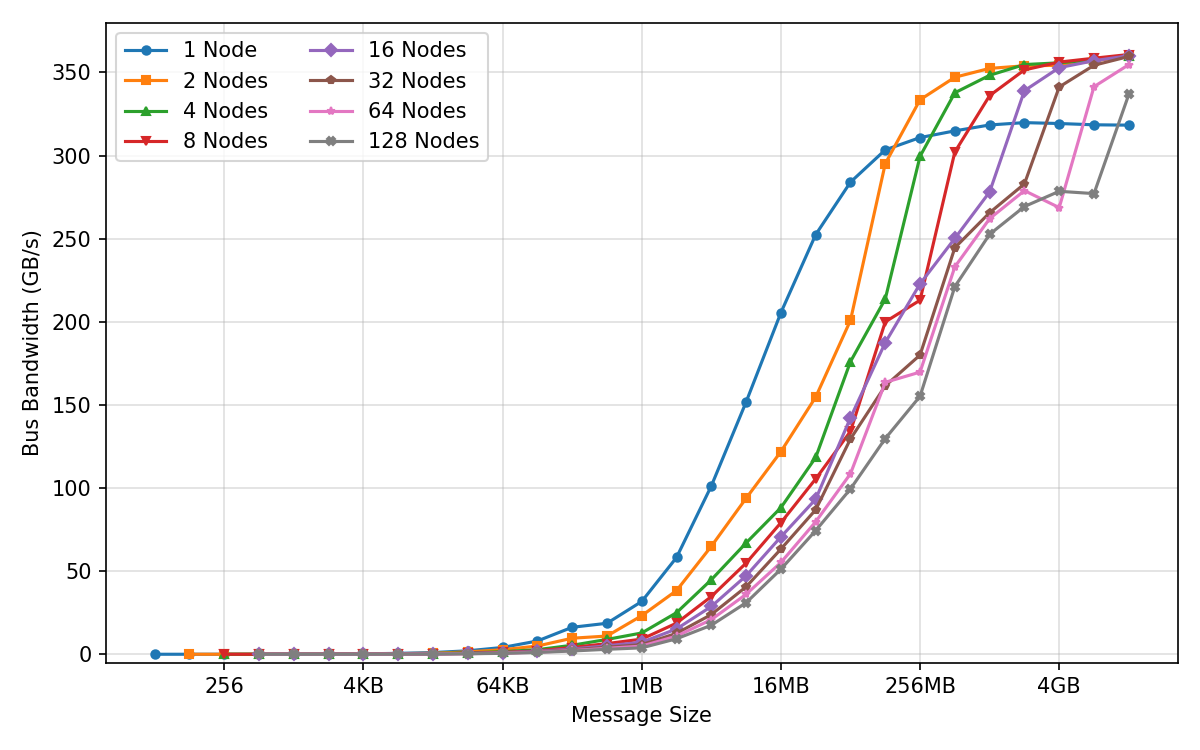

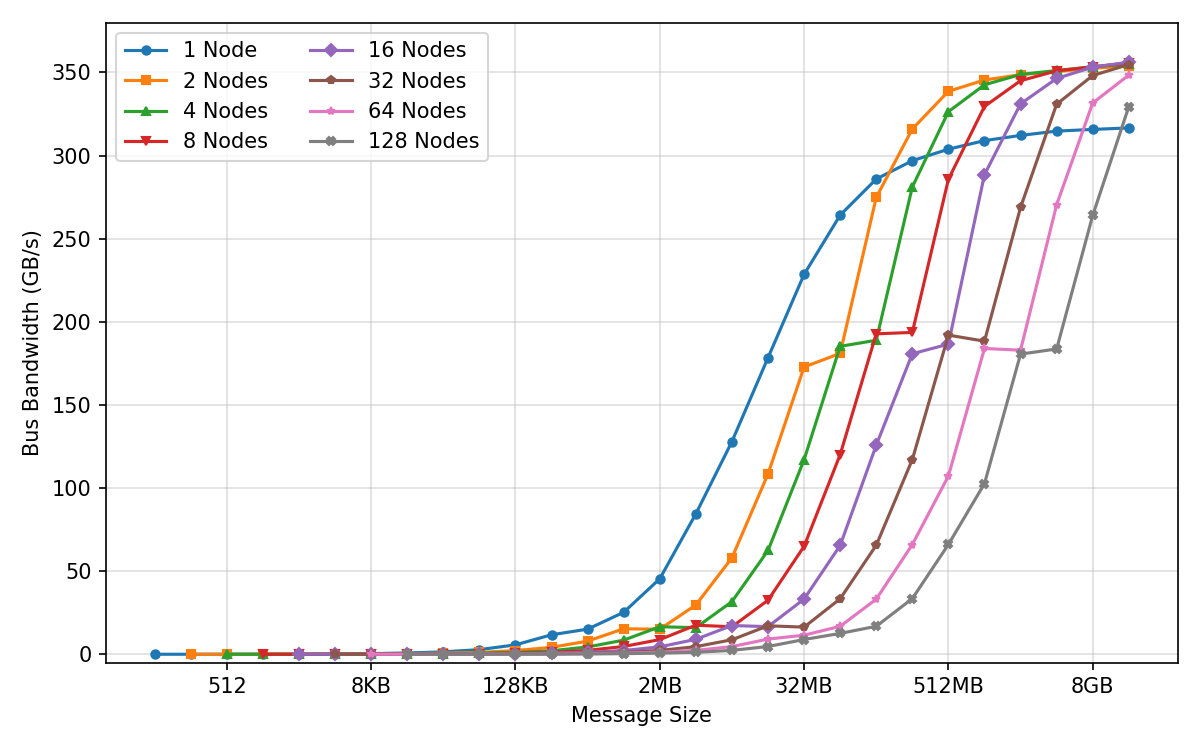

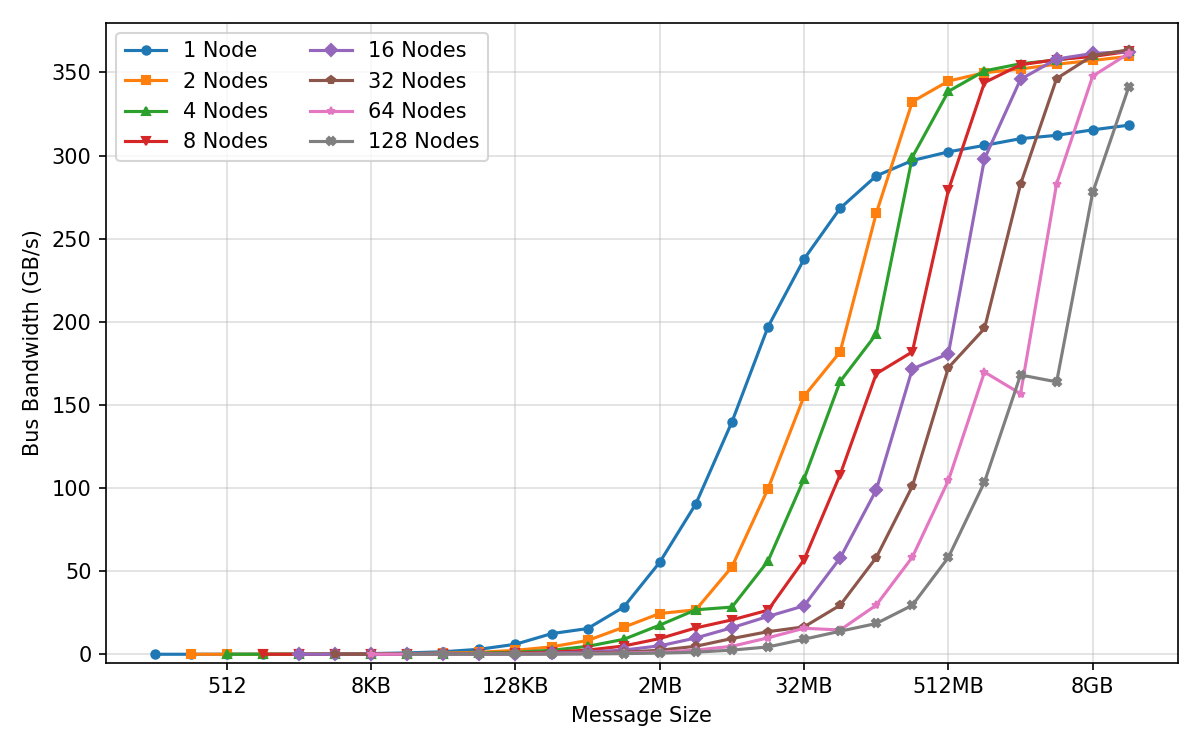

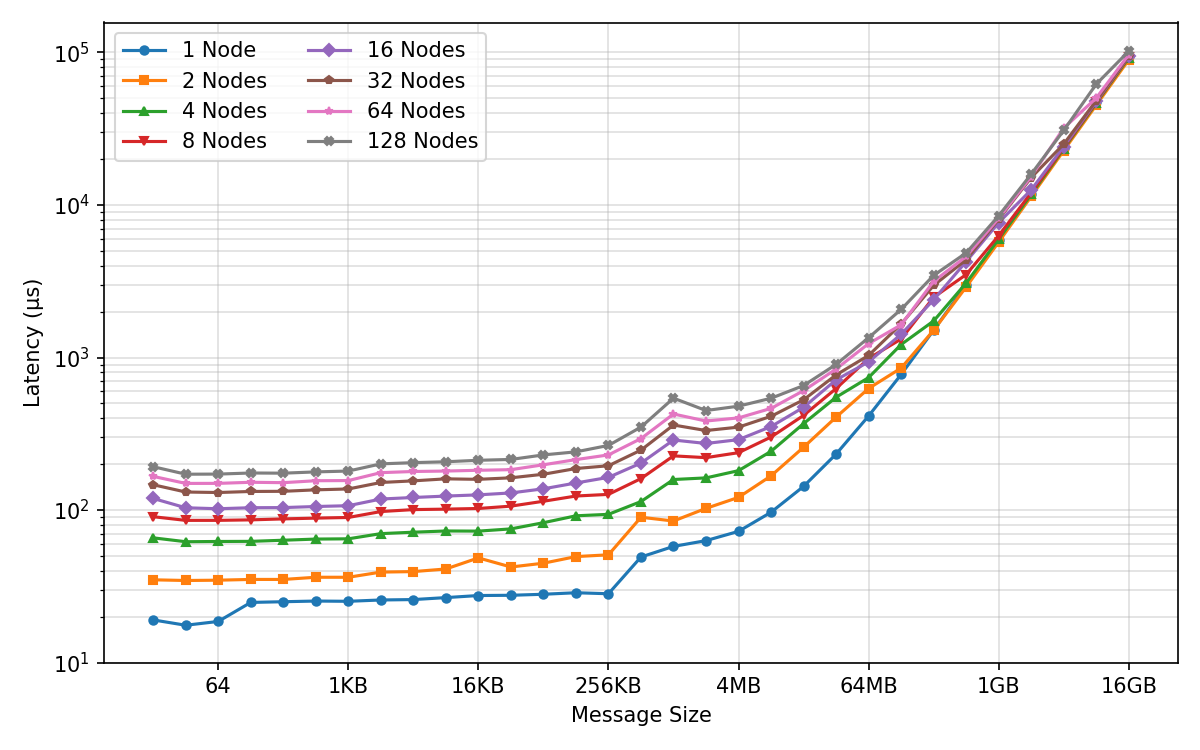

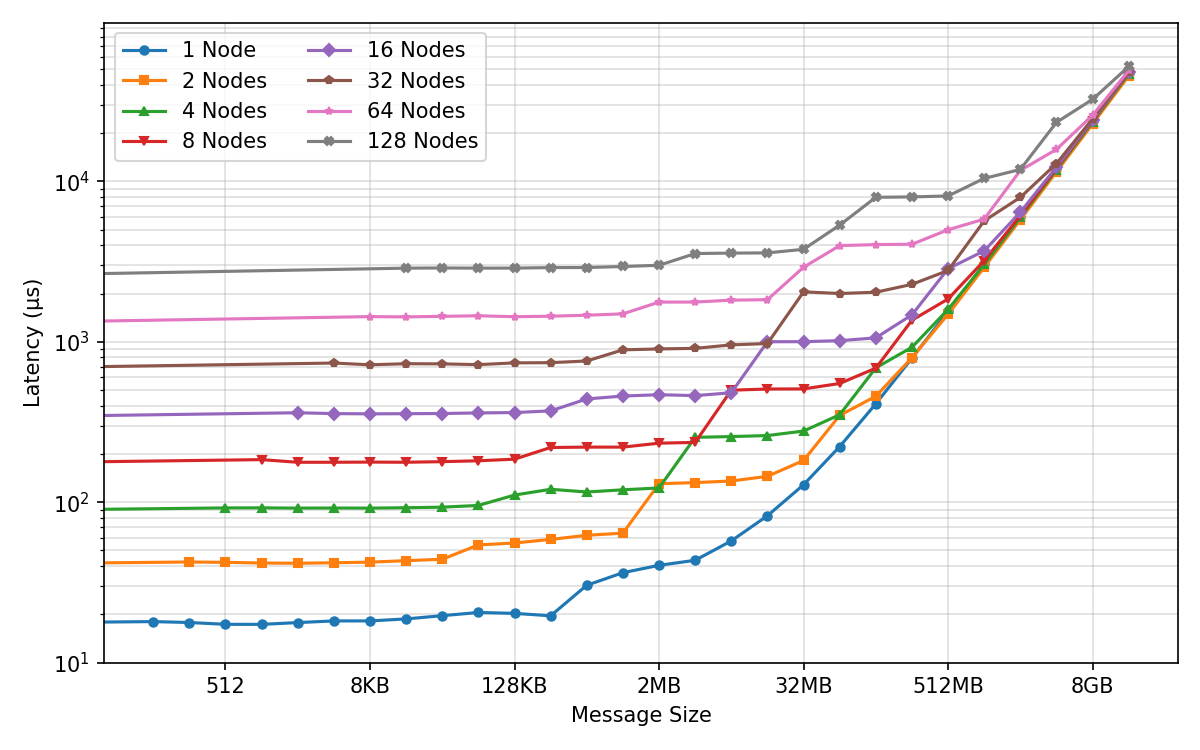

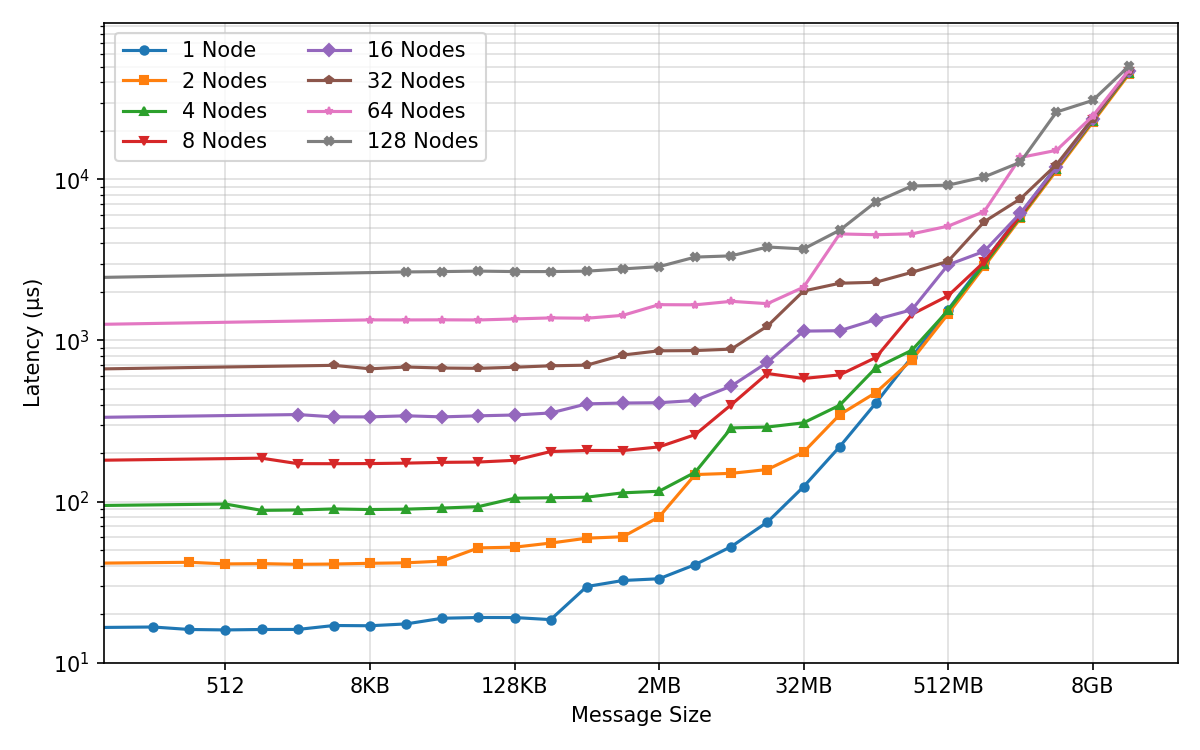

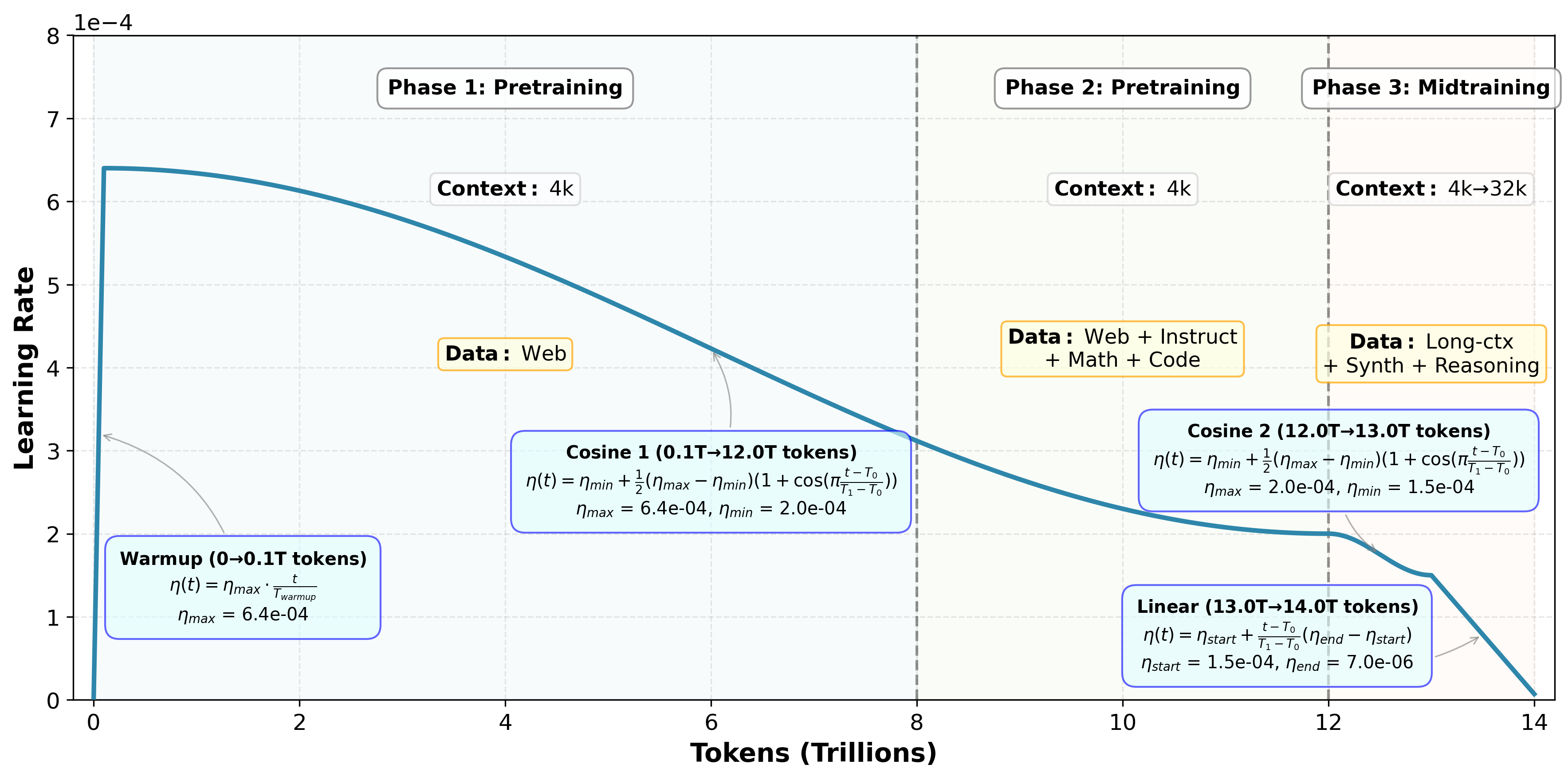

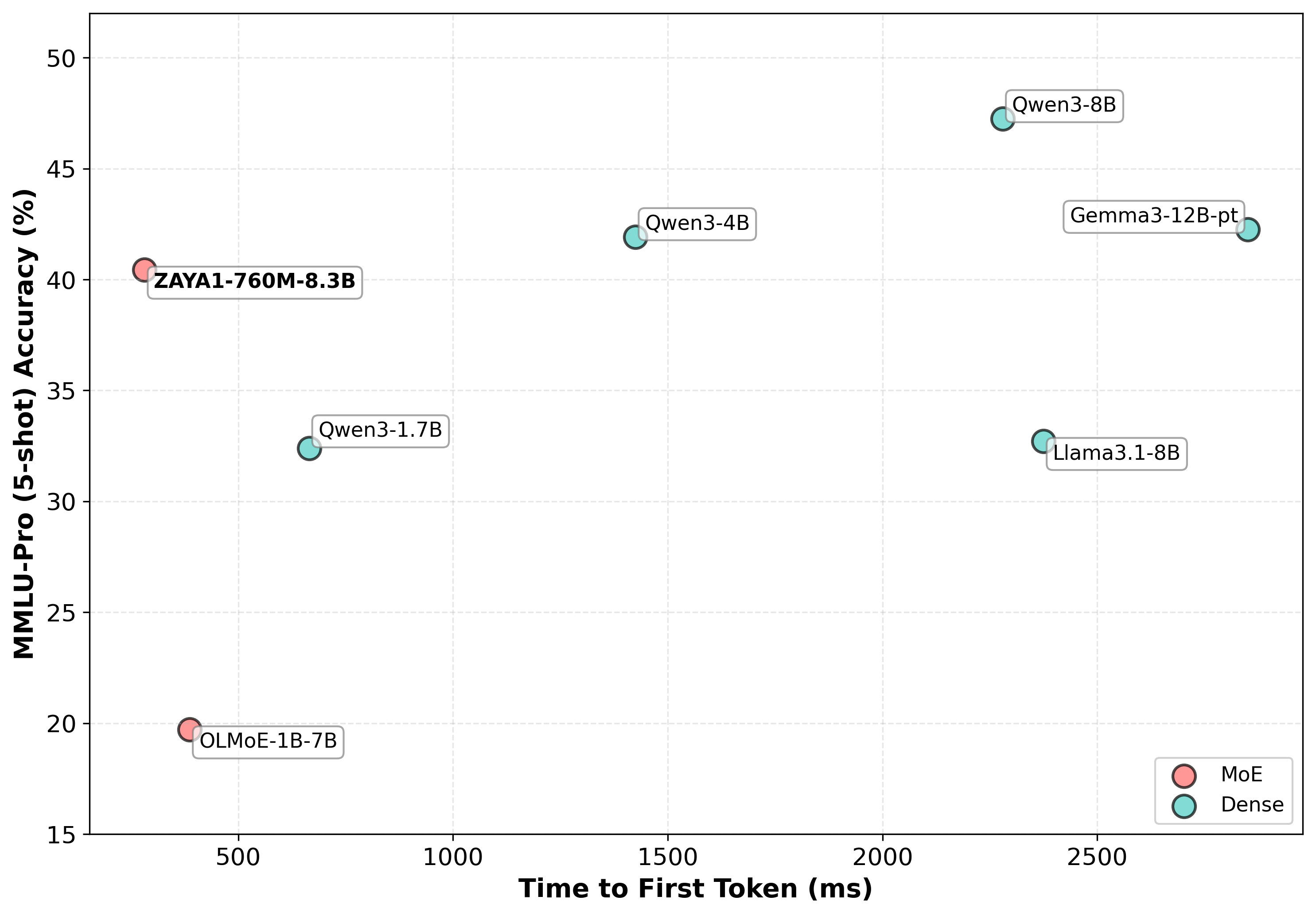

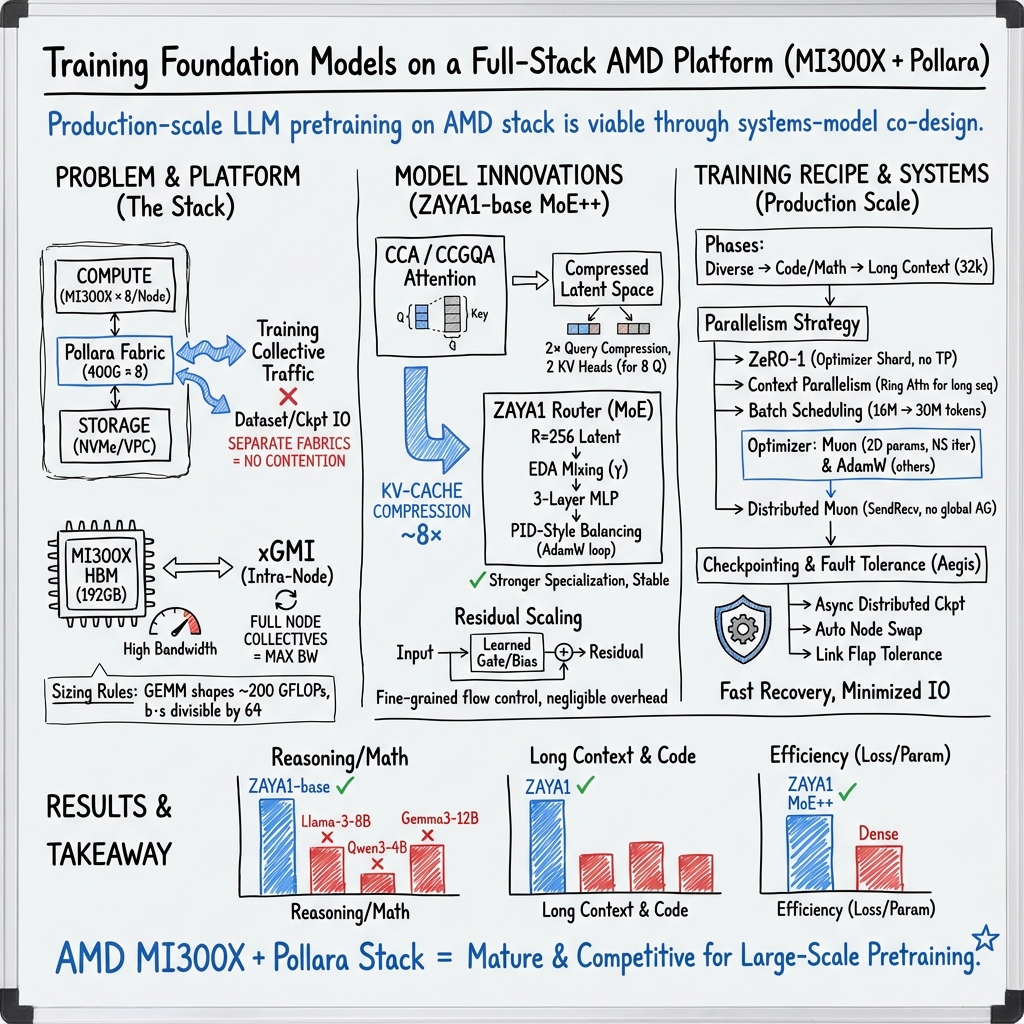

Abstract: We report on the first large-scale mixture-of-experts (MoE) pretraining study on pure AMD hardware, utilizing both MI300X GPUs with Pollara interconnect. We distill practical guidance for both systems and model design. On the systems side, we deliver a comprehensive cluster and networking characterization: microbenchmarks for all core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast) across message sizes and GPU counts on Pollara. To our knowledge, this is the first at this scale. We further provide MI300X microbenchmarks on kernel sizing and memory bandwidth to inform model design. On the modeling side, we introduce and apply MI300X-aware transformer sizing rules for attention and MLP blocks and justify MoE widths that jointly optimize training throughput and inference latency. We describe our training stack in depth, including often-ignored utilities such as fault-tolerance and checkpoint-reshaping, as well as detailed information on our training recipe. We also provide a preview of our model architecture and base model - ZAYA1 (760M active, 8.3B total parameters MoE) - which will be further improved upon in forthcoming papers. ZAYA1-base achieves performance comparable to leading base models such as Qwen3-4B and Gemma3-12B at its scale and larger, and outperforms models including Llama-3-8B and OLMoE across reasoning, mathematics, and coding benchmarks. Together, these results demonstrate that the AMD hardware, network, and software stack are mature and optimized enough for competitive large-scale pretraining.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper is like a field report from engineers who trained a large AI LLM using only AMD hardware (AMD MI300X GPUs and AMD’s Pollara network). They didn’t just train a model—they carefully measured how fast the hardware, memory, and network really are for this kind of work, tuned their software to match, and built a model called ZAYA1 that performs competitively with well-known models. Their goal was to show that the “full-stack” AMD setup is ready for serious, large-scale AI training.

What questions were they trying to answer?

Here are the main questions the team set out to answer:

- Can we train big, modern AI models efficiently using a complete AMD setup (GPUs, network, software)?

- How fast are the key parts—GPU compute, GPU memory, and networking—when used the way AI training actually uses them?

- What model shapes and settings (like layer sizes) work best on AMD MI300X GPUs?

- What tricks and tools (like fault tolerance and smart saving) are needed to keep long training runs stable and efficient?

- Can a model trained on this setup match or beat other strong models?

How did they do it?

To make this clear, think of the whole training system as a city with highways (networks), power plants (GPUs), and city planners (software). The authors:

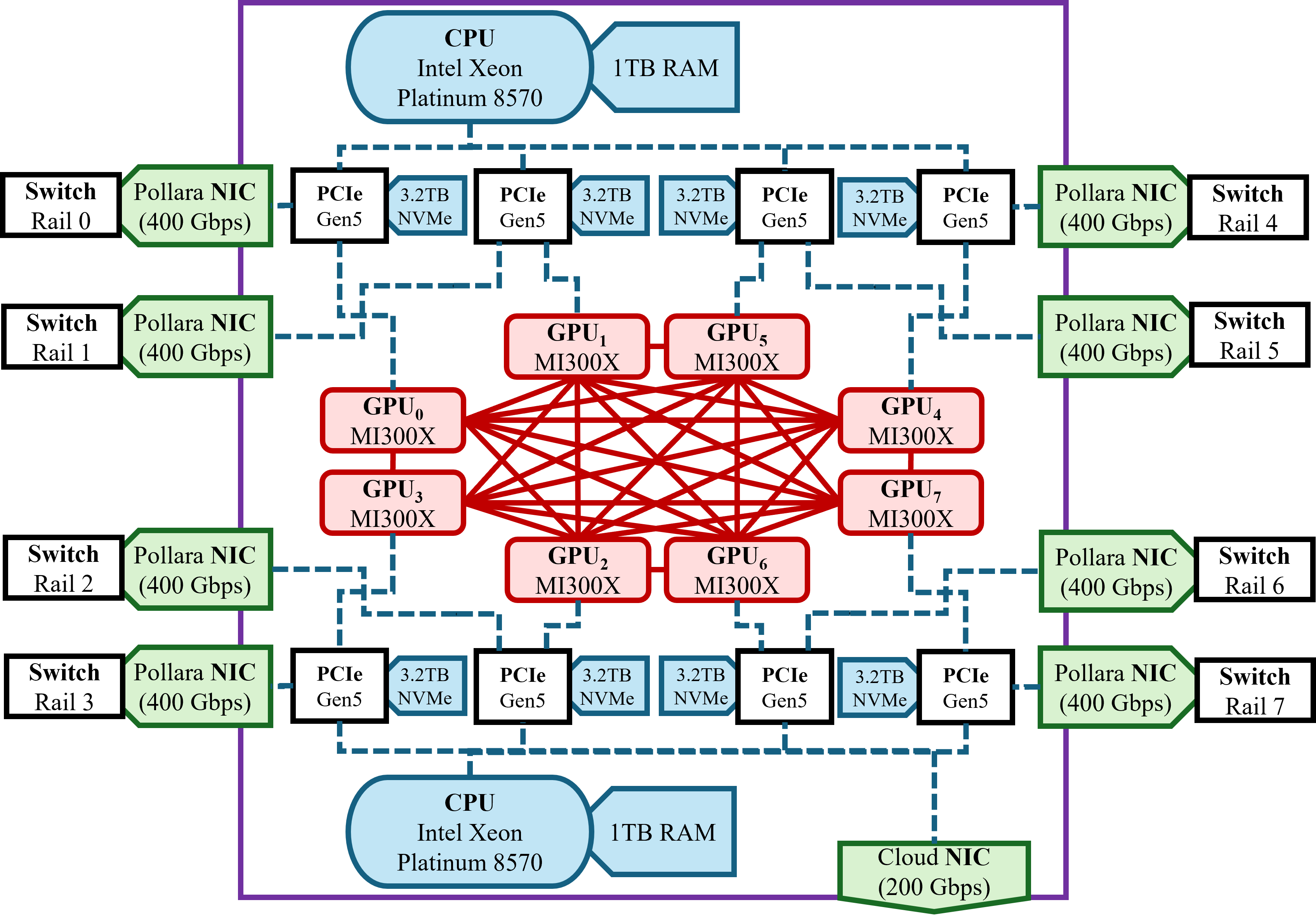

- Built the “city”: Each computer (node) has 8 AMD MI300X GPUs. Each GPU has its own super-fast network cable (a 400 Gbps Pollara NIC), like giving every car its own lane onto the highway. Inside a node, GPUs talk over a fast local link (InfinityFabric). There are two separate networks: one for training “chatter” between GPUs (the Pollara fabric) and one for file I/O like loading data and saving checkpoints (like having a separate road for delivery trucks so they don’t block commuters).

- Timed everything with “stopwatches” (microbenchmarks):

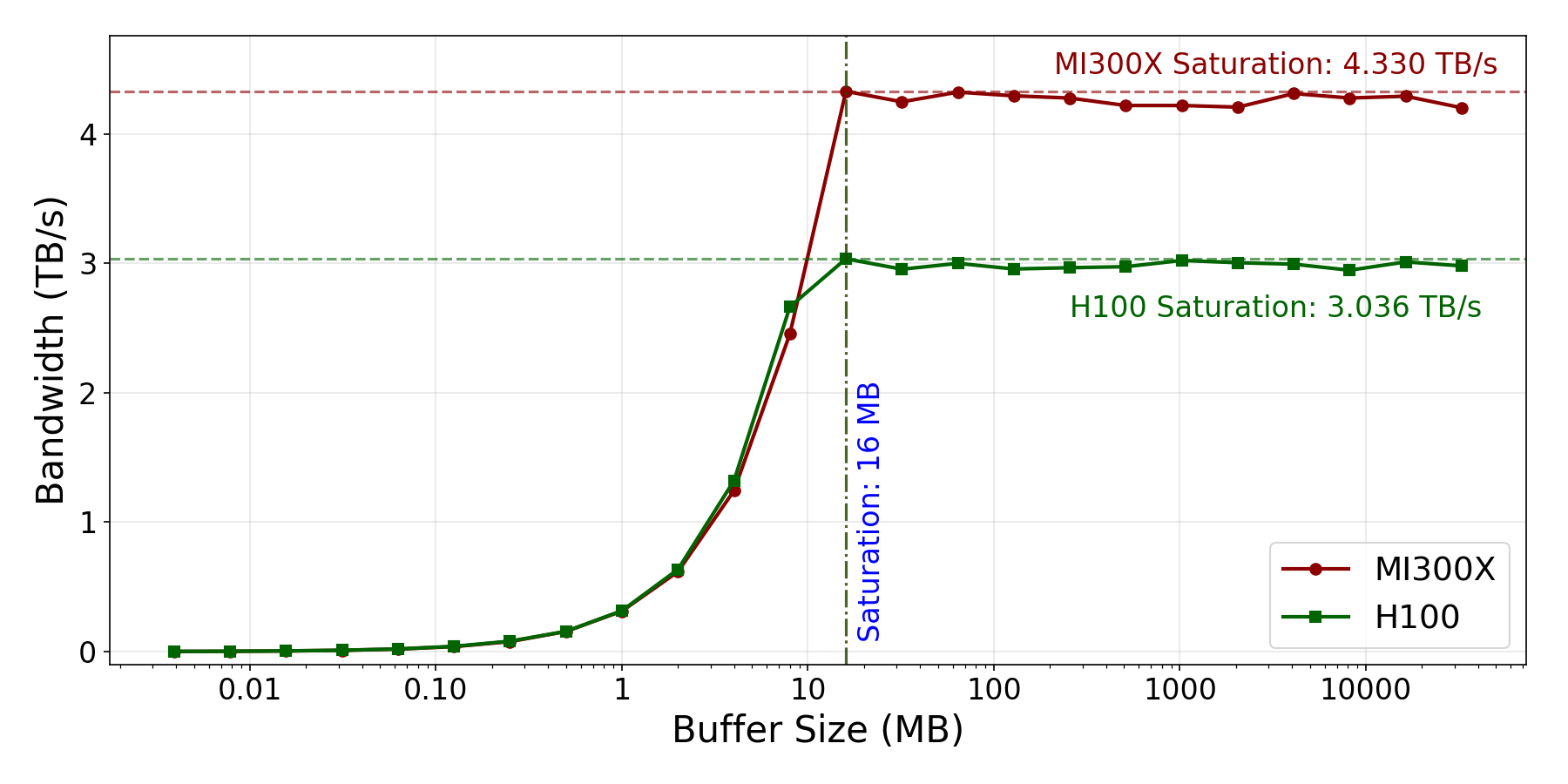

- Memory bandwidth: How fast can the GPU read/write its HBM memory? They used realistic tests (not just special show-off tests) to match real training behavior.

- Compute speed: They tested many sizes of matrix multiplications (GEMMs), which are the bread-and-butter math of AI models, and picked the fastest algorithms for each size.

- Network “group calls” (collectives): They measured how fast standard operations like all-reduce and all-gather run when many GPUs share information. They varied message sizes and number of GPUs to find the sweet spots.

- Designed the model to fit the hardware (like tailoring a suit):

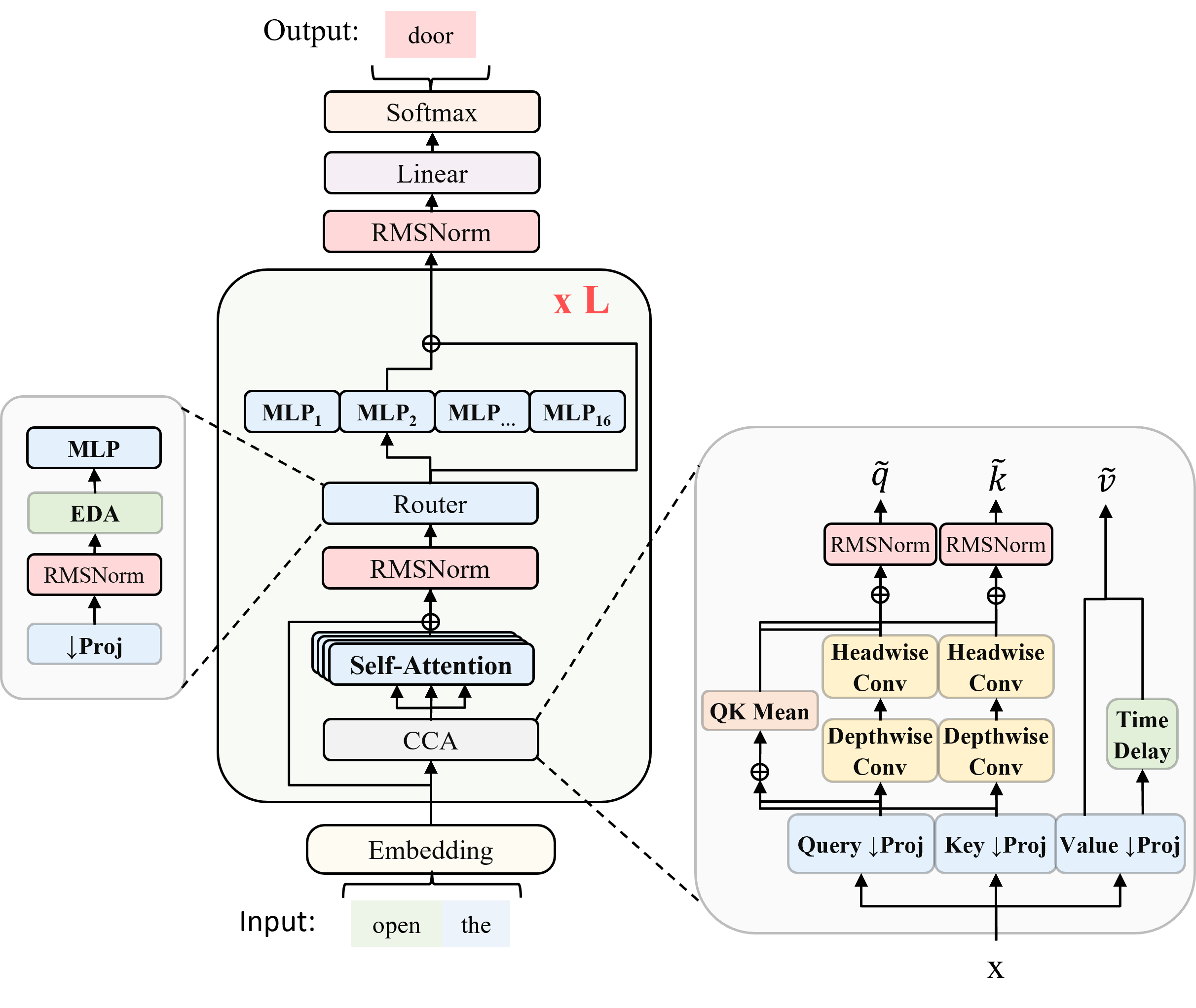

- They created ZAYA1, a mixture-of-experts (MoE) transformer. Think of MoE like a team of specialists: for each token, the model picks the best expert to handle it rather than making everyone work on everything.

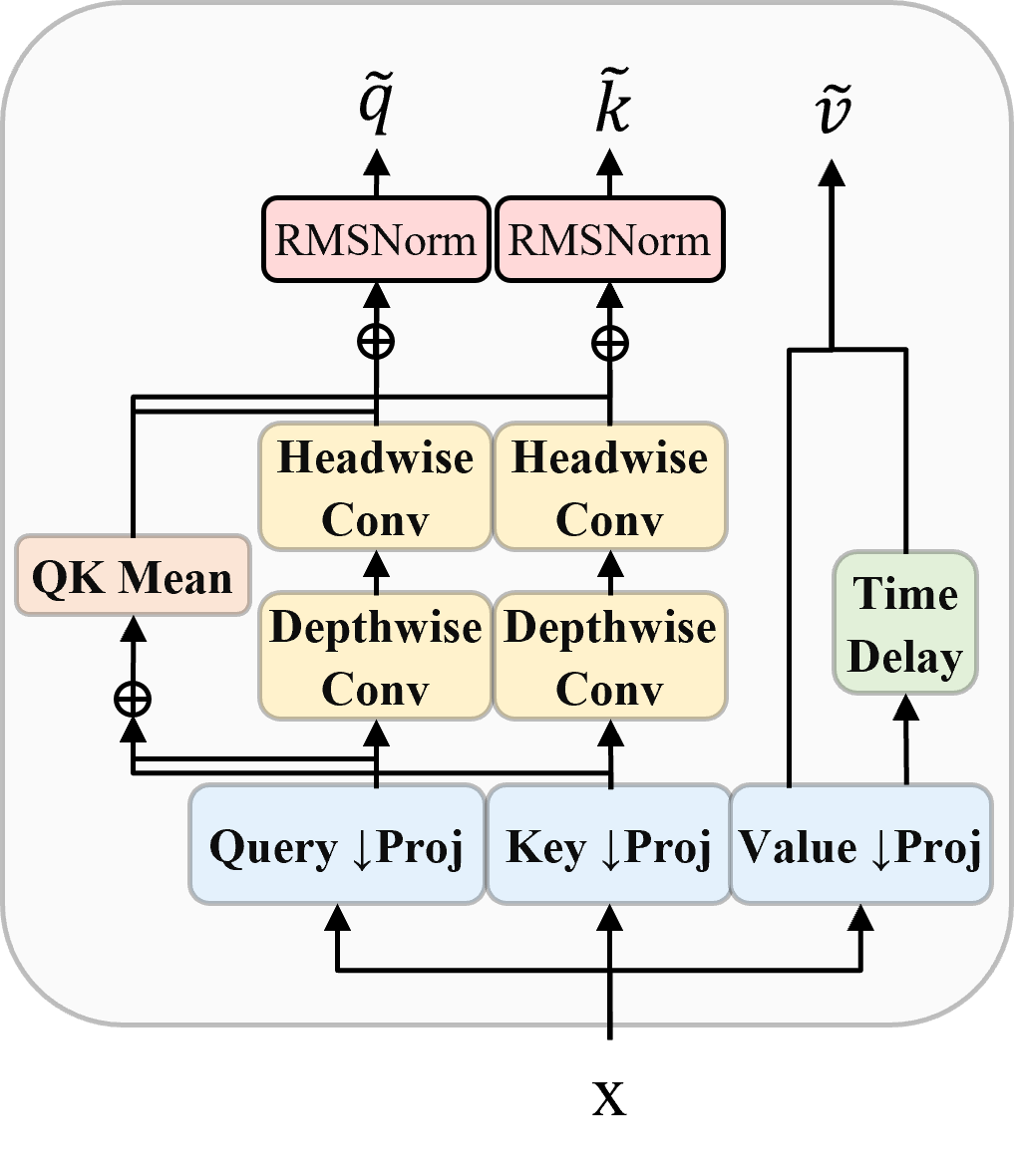

- They used CCA (Compressed Convolutional Attention), which does attention in a smaller “compressed” space, like taking notes instead of copying entire pages. This cuts compute and memory, especially for long inputs.

- They improved the “router” (the part that picks which expert handles which token) by using a small neural network (an MLP) with a memory of past choices (EDA). This helps specialists truly specialize and stay balanced.

- They added residual scaling, like giving each layer a volume knob to control how much information passes through.

- They tuned sizes (like hidden dimensions and head counts) to the shapes that AMD hardware likes best.

- Kept training stable and efficient:

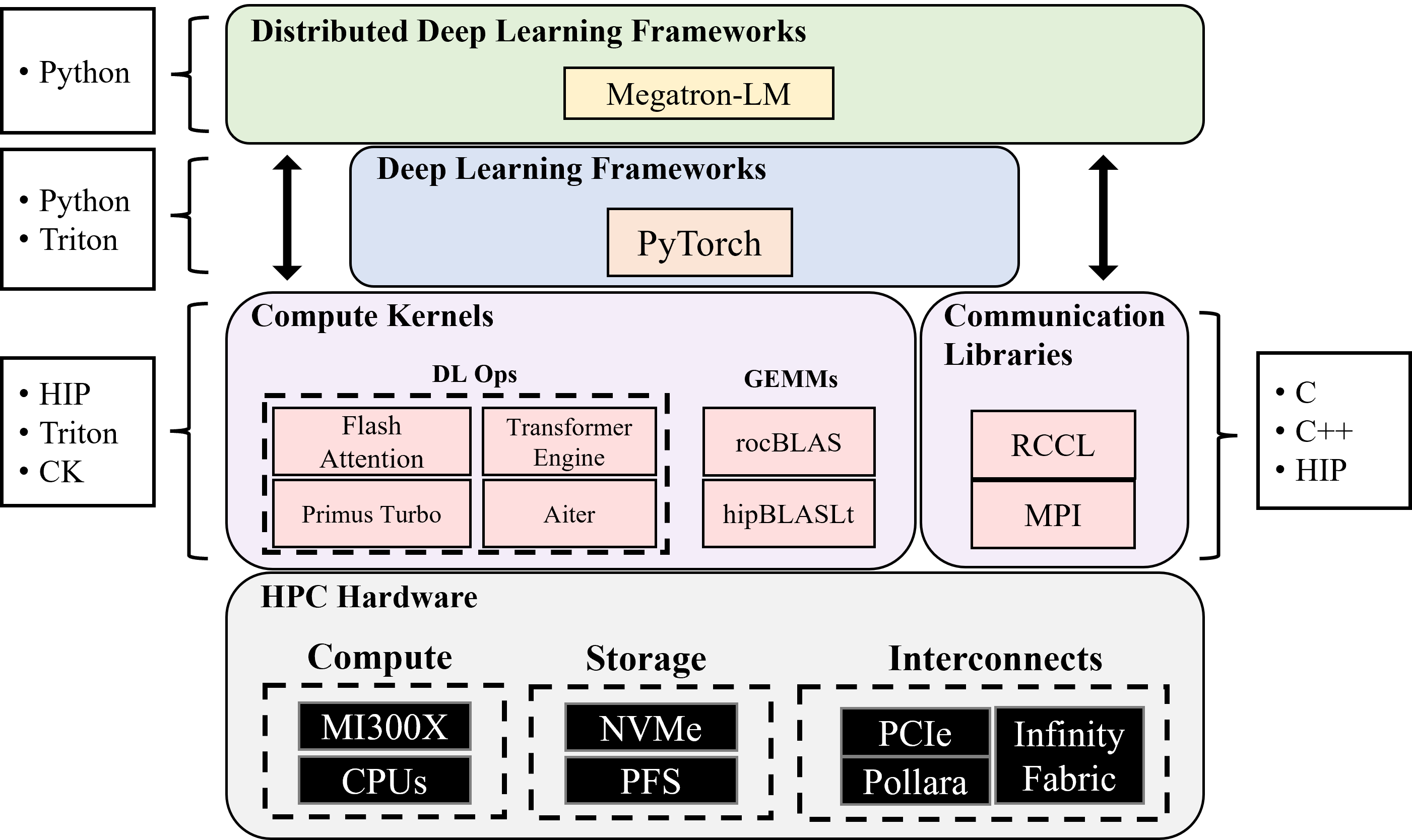

- They used Megatron-LM adapted to AMD’s ROCm stack, plus tools from AMD’s Primus.

- They used the Muon optimizer, which is memory-friendlier than AdamW and works well at large batch sizes.

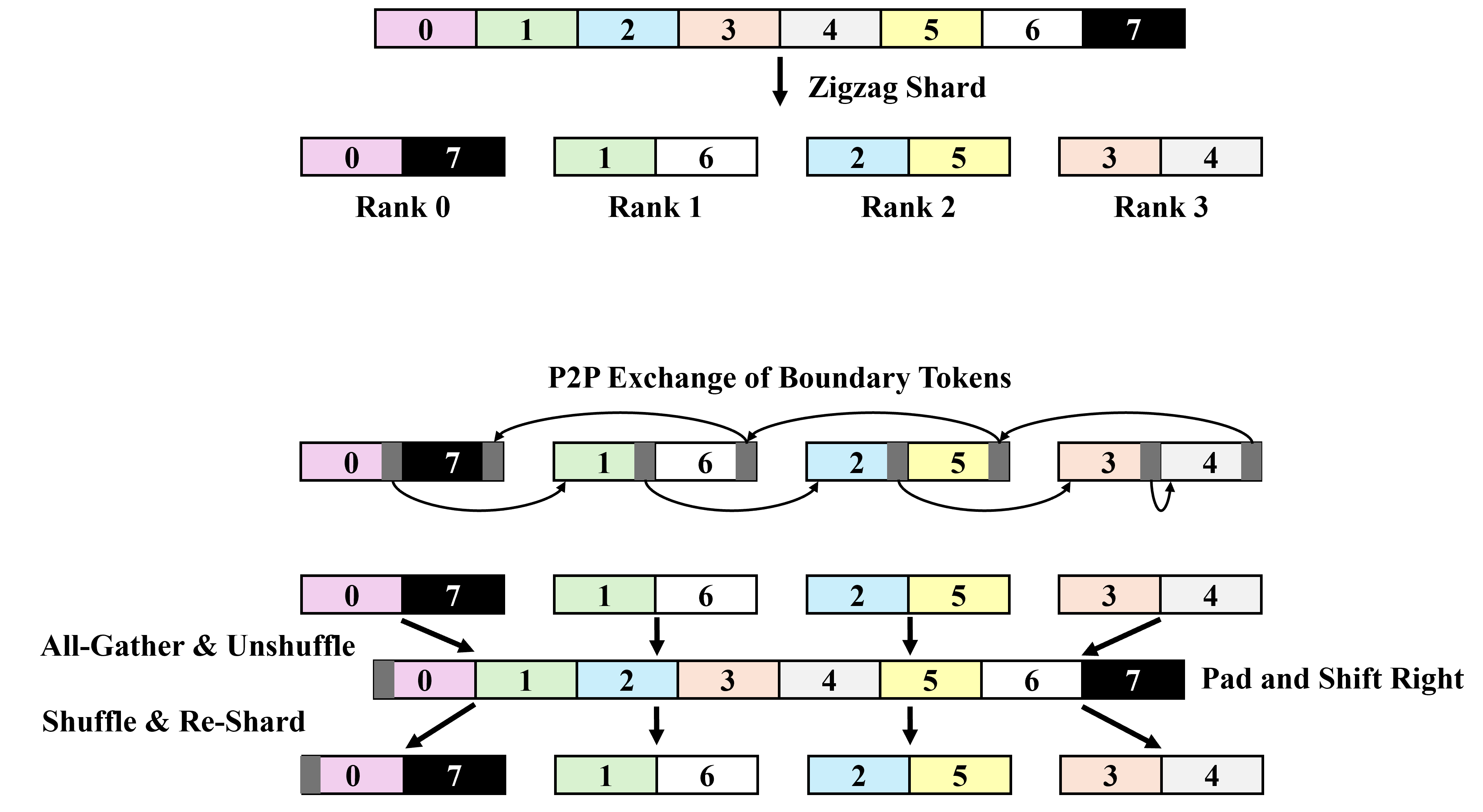

- They used simple data parallel training first, and later “context parallelism” (splitting the long input across GPUs) for very long sequences.

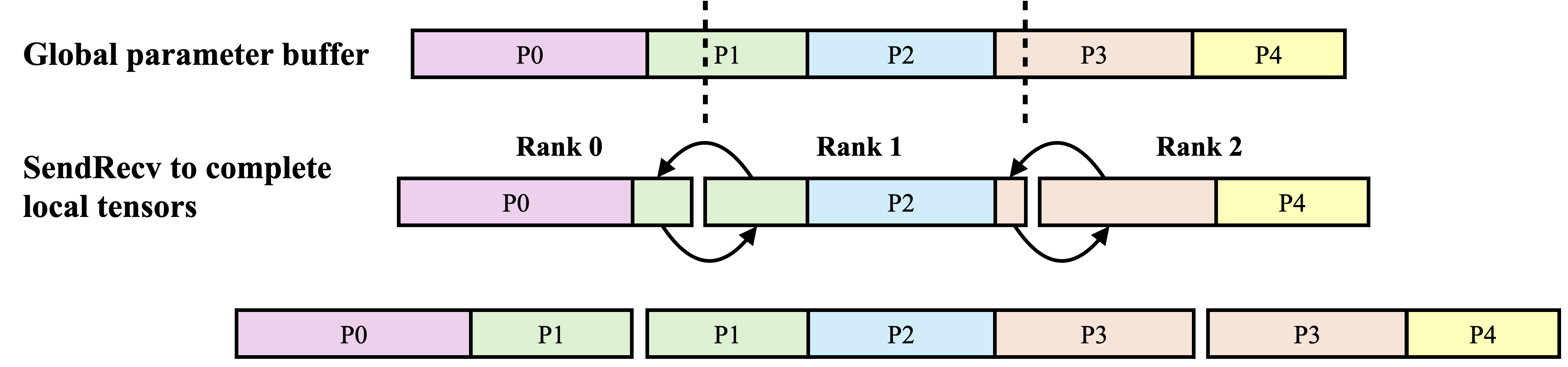

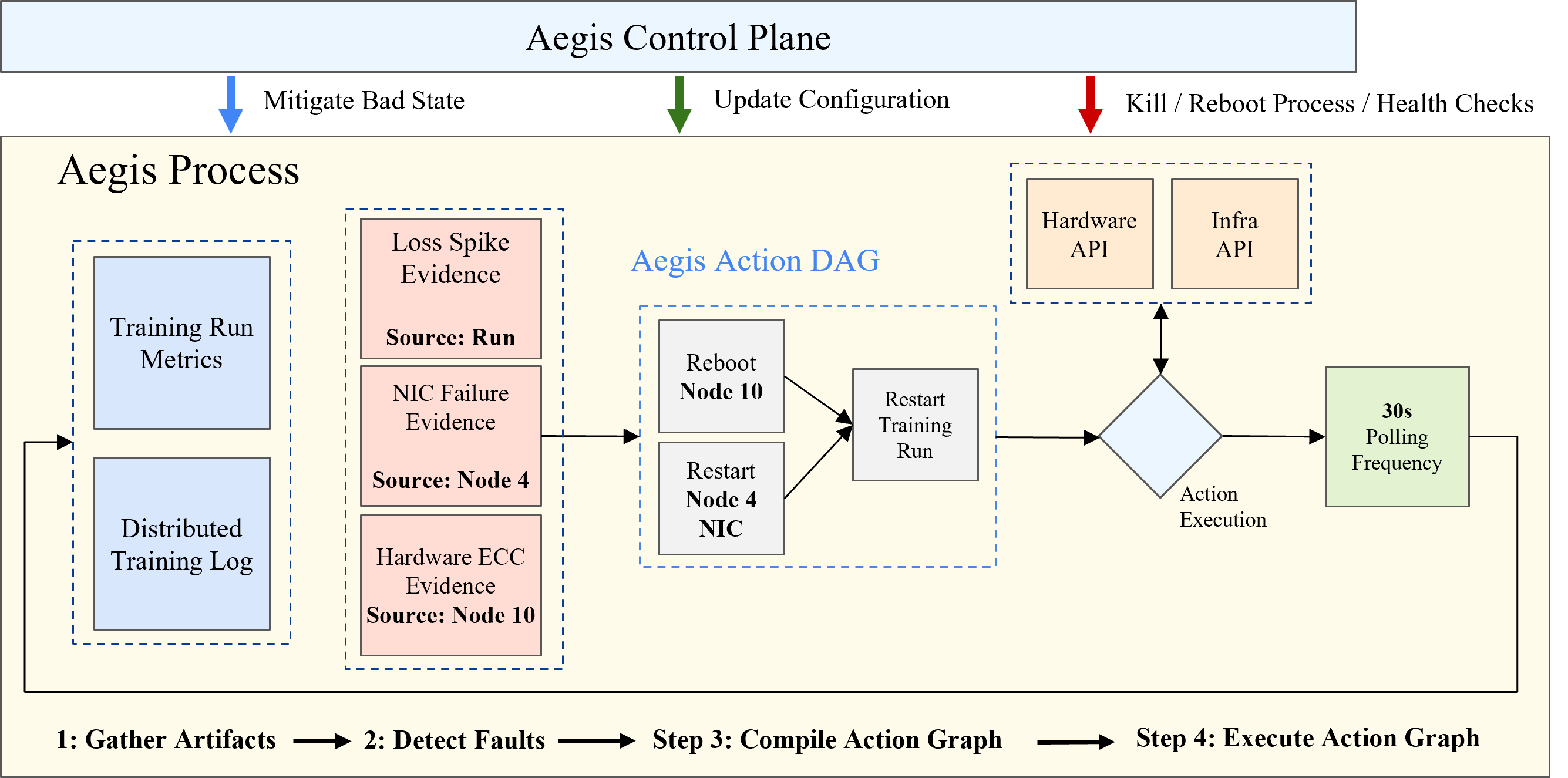

- They built practical tools for fault tolerance and “checkpoint reshaping” (think game save files that still work even if you change how the game is split across GPUs).

What did they find?

Below are the highlights of what mattered and what worked best:

- AMD end-to-end works at scale: The AMD GPUs (MI300X), networking (Pollara), and software (ROCm stack) are good enough today for competitive large-scale training.

- Memory matters, and they measured it realistically: They showed what sustained HBM memory bandwidth looks like for real AI workloads, not just perfect lab tests. This helps predict actual training speed.

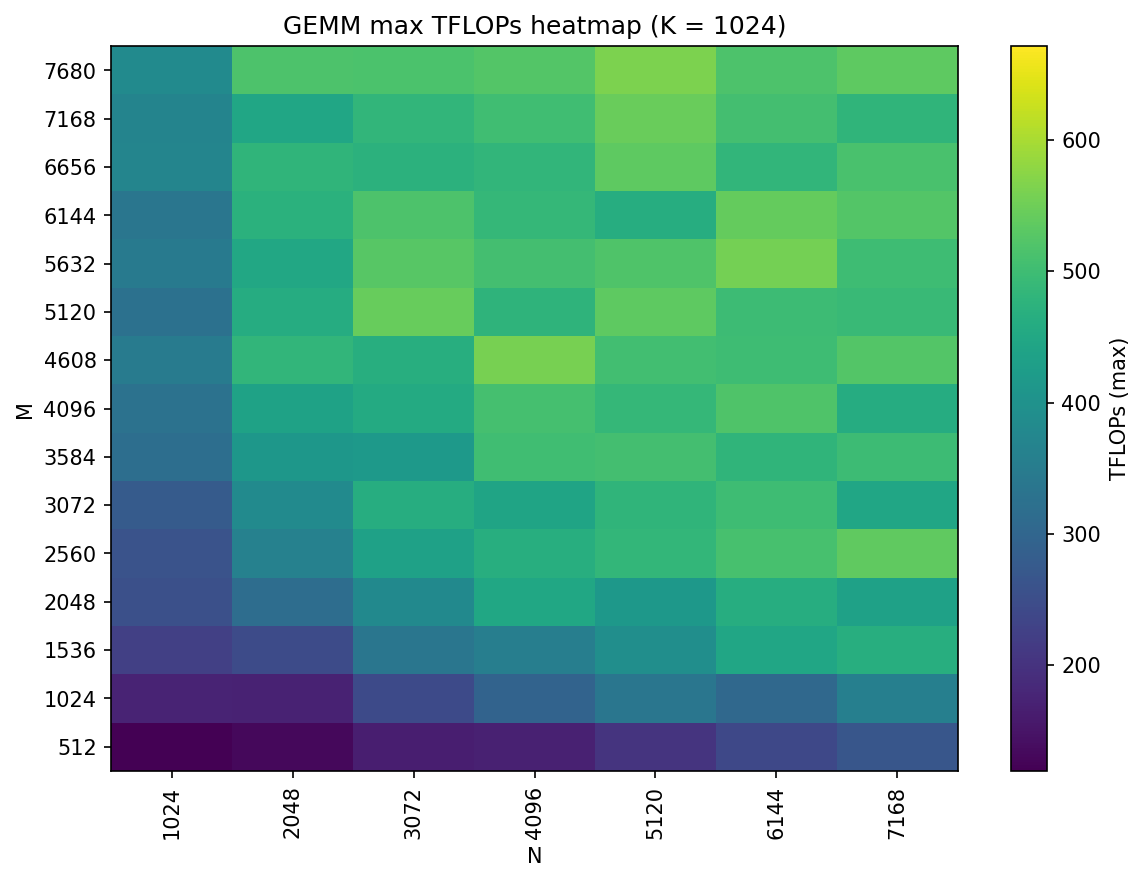

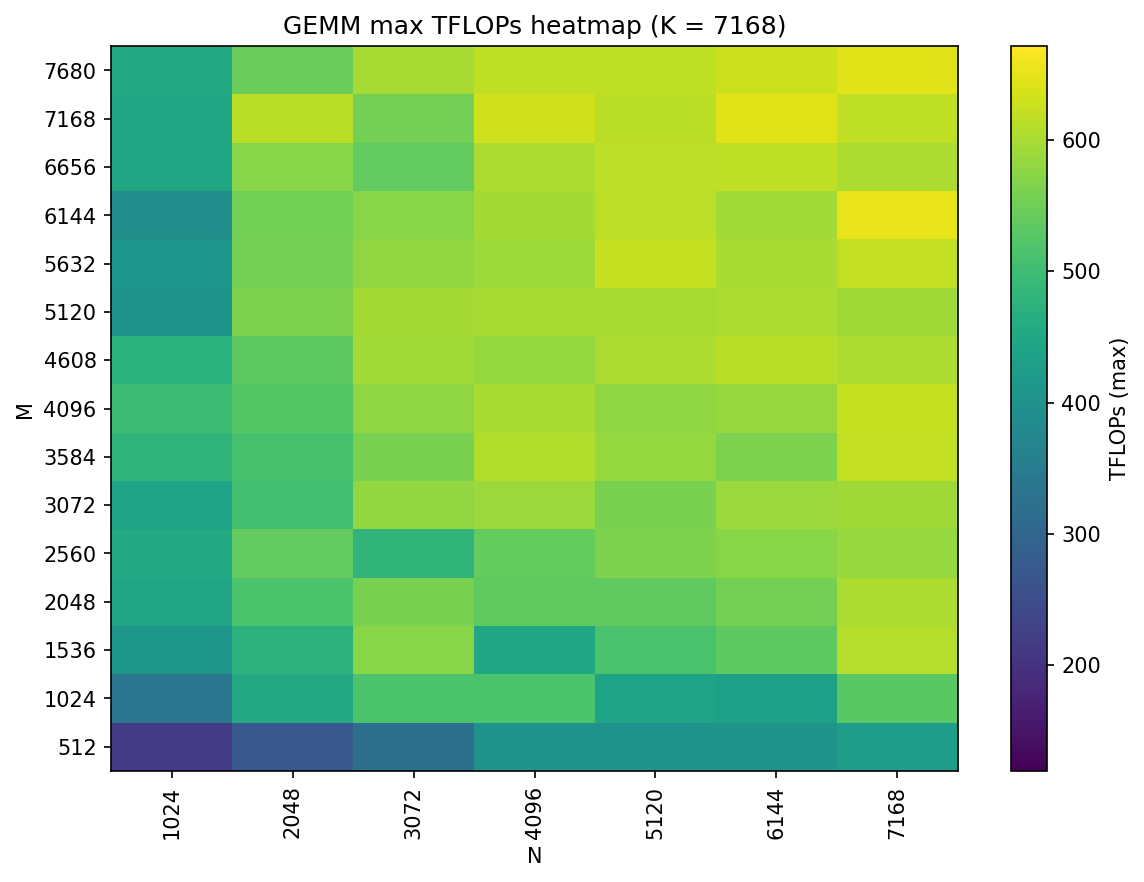

- Bigger, well-shaped matrix multiplies are faster: On MI300X, large GEMMs reach peak speed more easily, especially when the “inner size” (K) is bigger. They created lookup tables so the fastest algorithm is chosen automatically for each size.

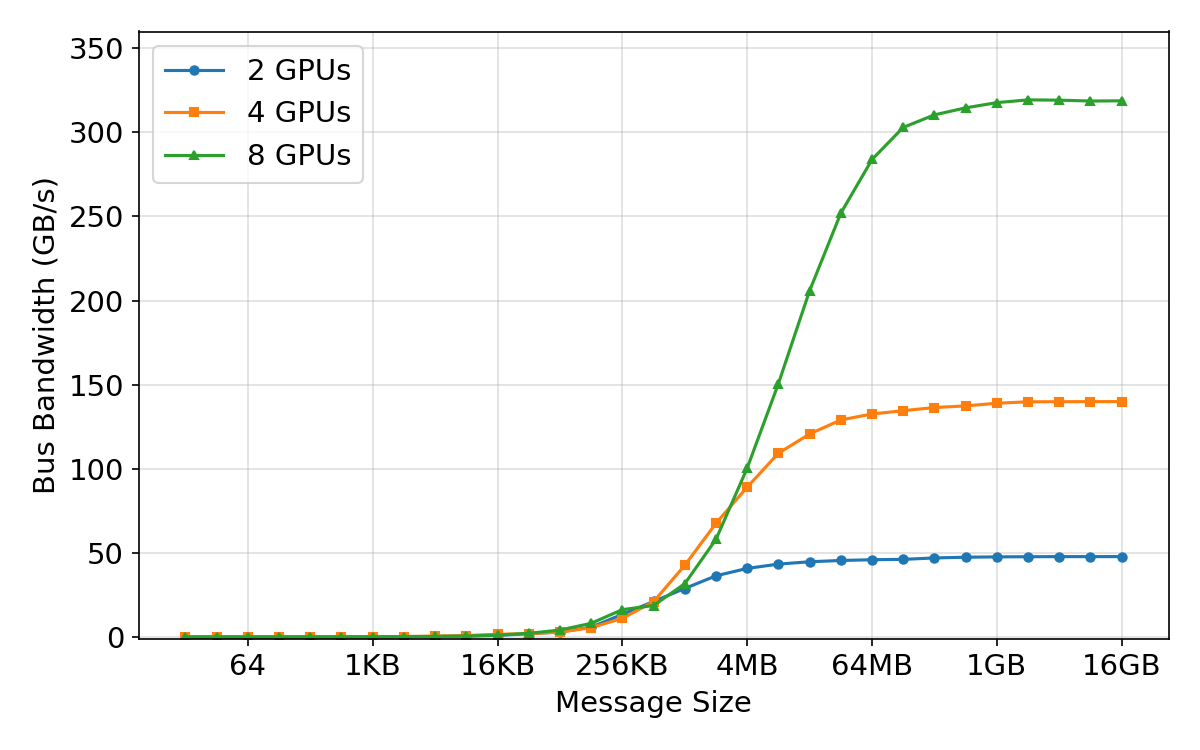

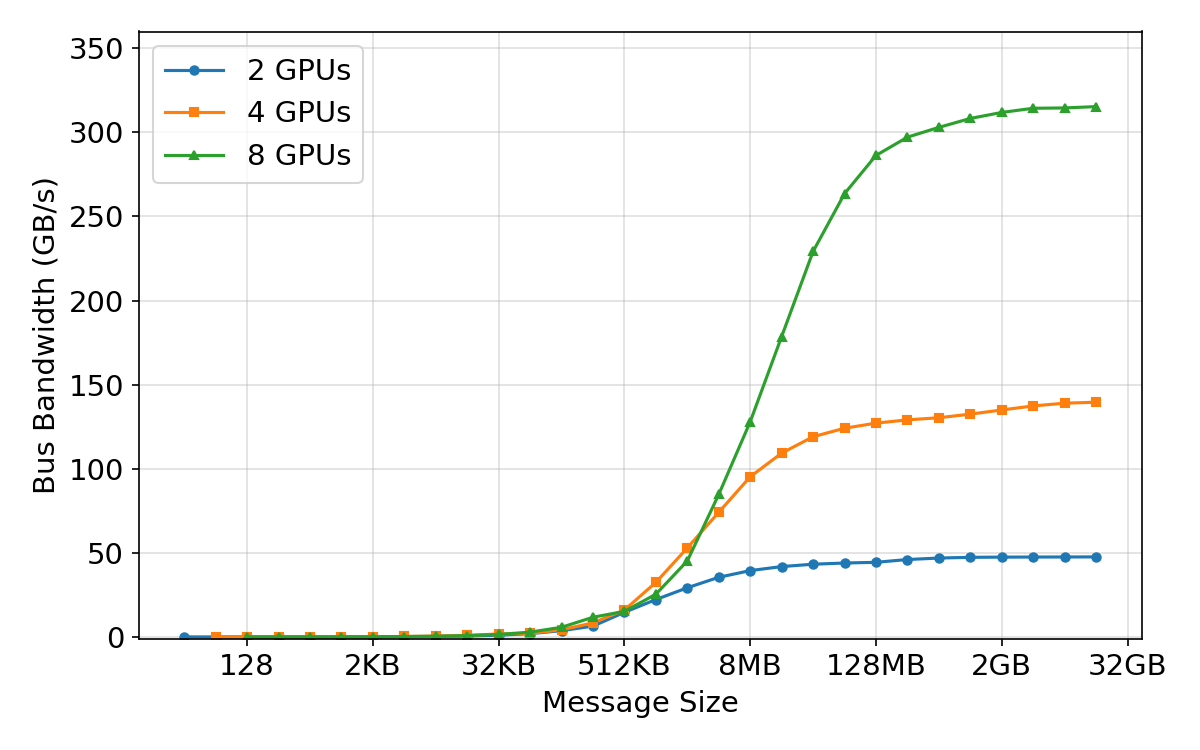

- Network efficiency depends on message size:

- Small messages are slow because of fixed overhead (latency), like waiting at many traffic lights.

- Bigger messages fill the “pipe” and hit max bandwidth.

- During training, they set the “fusion buffer” (how many gradients to bundle together) right at the point where bandwidth saturates—big enough to be fast, but not so big it’s hard to overlap with compute.

- Inside a node, AMD’s GPU link (xGMI) likes full participation: You get the best speed when all 8 GPUs in a node join a collective together. This influenced how they split the work (parallelism) so they avoid patterns that waste bandwidth.

- CCA attention helped a lot: Because CCA compresses attention, they cut both compute and memory, making long-context training (up to 32k tokens here) much cheaper. Training at 32k was almost as efficient as at 4k.

- Simple parallelism was enough, thanks to big GPU memory: Each MI300X has 192 GB HBM, so they could train with straightforward data parallelism for 4k context. For longer context, they added context parallelism without needing heavy tensor/expert parallelism across nodes.

- MoE design choices paid off:

- They used many small experts (fine-grained) with top-1 routing (pick one best expert), guided by a smarter router.

- This improved training speed and inference latency (responses are faster when only one expert runs).

- The router improvements made expert balancing easier and improved performance.

- ZAYA1 performed strongly:

- ZAYA1-base has about 760 million “active” parameters per token (because of top-1 experts) and 8.3 billion total parameters overall.

- It matches or beats models like Qwen3-4B and Gemma3-12B at similar or larger scales, and outperforms Llama-3-8B and OLMoE on reasoning, math, and coding tests.

Why does this matter?

This work is important for three big reasons:

- More choice in AI hardware: It shows that AMD’s full stack—GPUs, networking, and software—is ready for large-scale AI training, giving companies and researchers a real alternative to NVIDIA-based systems.

- Practical playbook for builders: The paper shares hard-won lessons on how to measure real performance, how to size model layers for the hardware, how to tune network message sizes, and how to keep long training jobs stable. This helps others avoid common pitfalls and get better speed for the same cost.

- Better models, cheaper and faster: Designs like CCA and a smarter MoE router let models handle long inputs and tough tasks more efficiently. That means faster training, quicker responses at inference time, and potentially lower costs—useful for everything from coding assistants to long-document understanding.

In short, the team shows that with smart engineering and model design, AMD hardware can train competitive AI models at scale. They provide clear measurements, practical rules of thumb, and a promising model (ZAYA1) that benefits from these choices—and that paves the way for even longer contexts and better performance in future work.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of concrete gaps the paper leaves open. Each item highlights what is missing or uncertain and points to actionable next steps for future work.

- Reproducibility artifacts are not provided: the internal Megatron-LM fork, ROCm patches, RCCL configuration, fused kernels (RMSNorm, optimizer), microbenchmark code, static GEMM tuning tables, and exact training configs (optimizer hyperparameters, fusion buffer sizes, RCCL env vars) are not released.

- Dataset composition and processing are under-specified: precise mixture ratios per phase, deduplication, filtering, quality scoring, multilingual balancing, contamination control with evaluation sets, and licensing/ethics safeguards are not described.

- Evaluation details are incomplete: the paper claims competitive performance but does not provide a full, reproducible benchmark suite (task lists, prompts, decoding params, seeds), statistical variance, or ablation-backed evidence across reasoning, math, coding, multilingual, and long-context tasks.

- Long-context capabilities are asserted but not validated: no quantitative evaluation at 32k (or further) is shown; the path to 128k is discussed but not empirically demonstrated; effects of RoPE base extension to 1M on retention and stability are unreported.

- Lack of end-to-end throughput/efficiency numbers: tokens/sec per GPU, iteration-time breakdowns with overlap, GPU utilization, and overall compute efficiency (vs hardware peaks) are not reported, making it hard to verify “competitive pretraining” claims.

- Energy/cost-efficiency unreported: no measurements of power draw, energy per token, thermal behavior, or TCO comparisons versus NVIDIA platforms.

- MoE capacity management unspecified: capacity factor, token dropping policy (and frequency), overflow handling, and their impact on quality/efficiency are not described for top-1 routing.

- Router ablations are missing: there is no quantitative comparison of the ZAYA1 router (MLP + EDA + PID-style balancing) against linear routers across scales, nor sensitivity to router dimension R, depth, EDA weight γ, PID hyperparameters, or balancing time-constants.

- Expert specialization evidence is limited: the paper asserts increased specialization but provides no metrics (expert entropy, mutual information, specialization clustering, expert drift over training, specialization persistence across domains).

- Stability under non-stationary data mixes is unexplored: how the router’s PID balancing reacts to rapid distribution shifts, curriculum transitions across phases, or long-context phases is unknown.

- MoE scalability without expert-parallel all-to-all is untested: ZAYA1 uses local experts (no inter-node all-to-all). It remains unclear how AMD Pollara/RCCL perform for expert-parallel all-to-all at larger MoE scales or higher top-k.

- Context-parallel (CP) design leaves training-time limitations unresolved: ring attention induces intra-node P2P traffic that underutilizes xGMI; a collective-friendly CP for training (analogous to tree attention) is not presented or benchmarked.

- Inference performance is not quantified: latency/throughput vs batch size, prompt length, and output rate; KV-cache memory footprint; top-1 vs top-2 routing trade-offs; serving stack details; dynamic batching; and quantization support on MI300X are not provided.

- CCA design space is underexplored: no systematic sweep over query/KV compression ratios, kernel sizes, grouped/depthwise conv choices, or head fraction choices; trade-offs in quality vs speed/KV compression across sequence lengths are not shown.

- CCA failure modes are uncharacterized: impact on in-context learning, long-range recall beyond 32k, cross-attention behavior under extreme sparsity, and sensitivity to token distributions remain open.

- GEMM tuning robustness is unclear: static lookup tables may be brittle across ROCm/firmware versions and shape drift due to MoE imbalance; there’s no evaluation of dynamic tuning overhead, cold-start behavior, or fallback performance.

- HBM bandwidth measurement generality is limited: benchmarks focus on contiguous memcpy-like patterns; non-contiguous, strided, or scatter/gather access patterns common in modern kernels (e.g., FlashAttention, fused ops) are not profiled.

- RCCL microbenchmarks omit all-to-all and tail behavior: only core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast) are shown; all-to-all performance, tail latency under load, multi-job interference, and failure-induced retransmissions are not evaluated.

- Rails-only topology trade-offs are not quantified end-to-end: the penalty vs Clos under real training workloads, sensitivity to cross-rail traffic, congestion hotspots, and job placement strategies are not analyzed.

- Fault tolerance lacks quantitative validation: checkpoint size/throughput, reshape latency, recovery time objective (RTO), failure injection experiments (e.g., GPU/node loss mid-step), checkpoint integrity checks, and metadata/versioning resilience are not reported.

- ZeRO stage choices are narrow: only ZeRO-1 is used; trade-offs versus ZeRO-2/3 on MI300X (with lower HBM or larger models) and their RCCL traffic patterns are untested.

- Global batch scheduling is not ablated: increasing from 16M to 30M tokens improves throughput, but effects on generalization, optimization stability (with Muon), and per-expert gradient noise scale are not quantified.

- Muon optimizer analysis is incomplete: computational overhead of 5 Newton–Schulz iterations, sensitivity to iteration count, numerical stability in bf16, memory/computation savings vs AdamW, and quality/efficiency trade-offs across tasks and scales are not provided.

- Precision modes are limited: no results with FP8 (supported on MI300X), mixed-precision variants, or stochastic rounding—potentially leaving significant performance on the table.

- Portability to smaller-memory GPUs is not addressed: the design depends on 192 GB HBM (ZeRO-1 only, large microbatches). Guidance for 80–120 GB-class GPUs (e.g., MI250, A100/H100) is missing.

- Multi-tenant and heterogeneous cluster behavior is untested: Pollara/RCCL performance under co-scheduled jobs, mixed message sizes, and overlapping training/inference workloads is not assessed.

- Software maturity caveats are not enumerated: ROCm/RCCL “nuances that materially affect throughput” are mentioned but not listed concretely (e.g., required env vars, known bugs/workarounds, topology hints), limiting transferability.

- Data I/O pipeline lacks measurement: end-to-end dataloader throughput, prefetch depth, NVMe/OS cache effects, compression formats, CPU pinning, and the achieved overlap with GPU compute are not reported.

- Security/compliance considerations for data are absent: PII handling, redaction, and auditability of dataset curation are not documented.

- Scaling laws and compute–data trade-offs are not studied: no empirical scaling curves vs parameters/tokens; no analysis of small-MoE vs dense models at fixed FLOPs on this hardware.

- Generality across domains and languages is unclear: although multilingual data is included, there is no domain- or language-specific evaluation to confirm benefits or detect regressions.

- Comparison to NVIDIA baselines is missing: without side-by-side end-to-end training/inference and network comparisons (e.g., H100 + IB 400G), it is hard to contextualize the “mature and optimized” claim for the AMD stack.

- Kernel availability and integration gaps remain: it is unclear whether all kernels (FlashAttention variants, convs for CCA, fused norms, fused optimizer ops) are production-ready in ROCm TE or require custom forks.

- Expert count/topology design rules are incomplete: guidance for expert count per layer, local vs global experts, and how to transition to expert-parallel all-to-all as model size grows is not provided.

Practical Applications

Practical, real-world applications derived from the paper

Below are actionable applications grounded in the paper’s findings, methods, and system innovations. Each item includes sector linkages, potential tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

- AMD-first LLM pretraining pipelines for industry AI teams

- Sector: software, cloud/AI infrastructure

- What: Port NVIDIA workflows to ROCm by replicating the paper’s end-to-end training stack (Megatron-LM fork + AMD Primus components, RCCL communication, hipBLASLt/rocBLAS GEMM tuning, Muon optimizer).

- Tools/workflows: ROCm, RCCL, Primus (monitoring + kernels), PyTorch TunableOp, TransformerEngine, hipBLASLt-bench, fused RMSNorm/LN, hardening fault-tolerance and checkpoint reshaping services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to MI300X GPUs and Pollara networking; ROCm maturity; internal engineering capacity for kernel selection/tuning; robust data pipelines.

- Cost-efficient rails-only network design for large-scale training clusters

- Sector: data center/HPC, cloud infrastructure

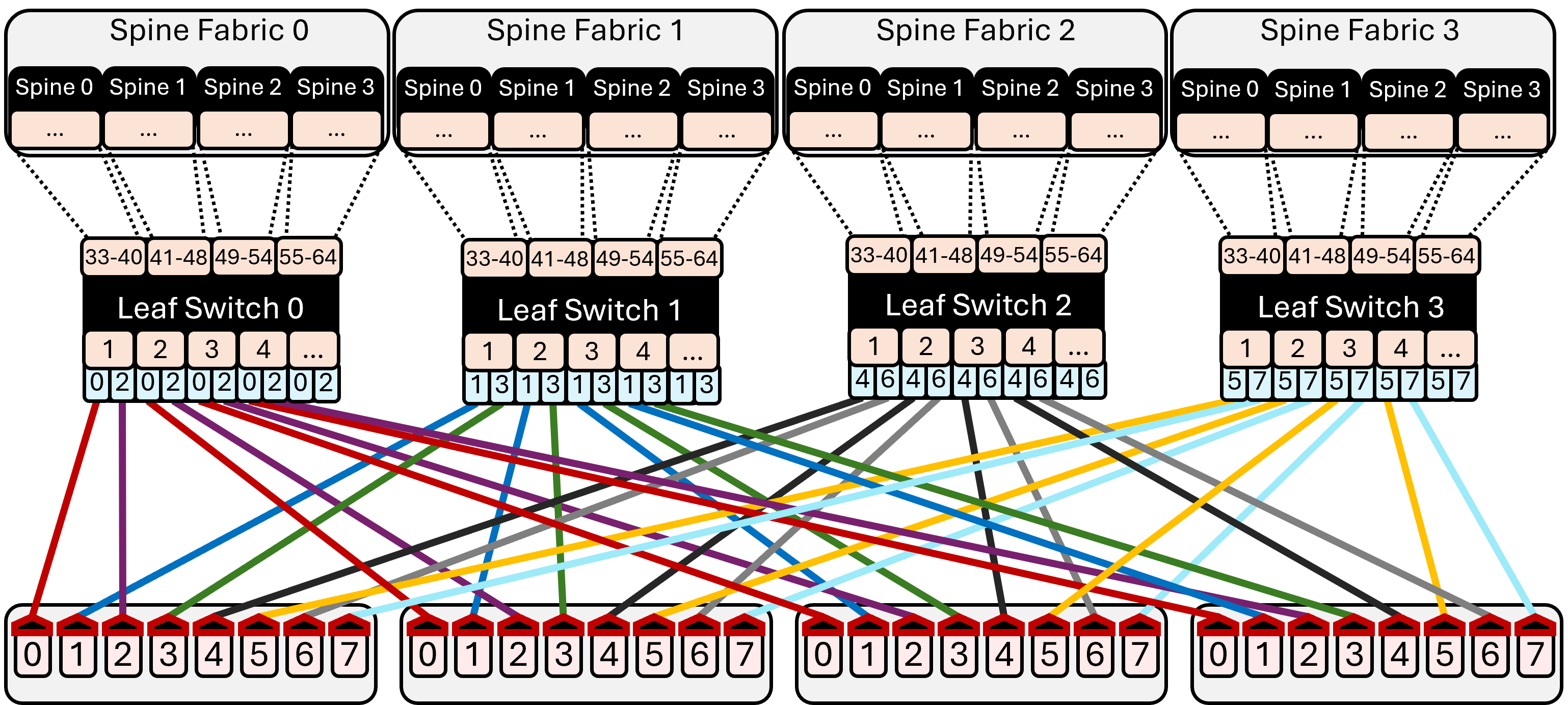

- What: Adopt the two-level rails-only topology with per-GPU Pollara NICs to reduce switch cost and wiring complexity, separating training fabric from VPC/storage networks to avoid IO contention.

- Tools/workflows: Pensando Pollara 400Gbps per-GPU NICs, dual fabric (training vs VPC/storage), GPU-direct RDMA, cluster placement that minimizes cross-rail traffic.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate mapping of parallelism topology to rails-only fabric, sufficient message sizes to saturate bandwidth, appropriate collective algorithm selection.

- Performance tuning via AMD-specific collective and memory microbenchmarks

- Sector: software, HPC

- What: Use the paper’s microbenchmarks to calibrate fusion buffer sizes (e.g., gradients) to the bandwidth “saturation point,” select two-level collective algorithms, and avoid small-message latency regimes on Pollara/InfinityFabric.

- Tools/workflows: RCCL collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather), intra-node xGMI-aware collectives, PyTorch memcpy kernel tuning, BabelStream-like memory access benchmarking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Awareness of xGMI constraints (full-node participation for max bandwidth); accurate fusion-buffer sizing; observability of iteration breakdowns.

- Hardware-aware transformer sizing and kernel shape optimization

- Sector: software, robotics (onboard compute), energy (edge analytics), finance (low-latency inference)

- What: Apply MI300X-aware sizing (GEMM shapes, divisibility constraints, batch scheduling) to maximize BF16 throughput and training stability; target ~200 GFLOPs per GEMM for peak throughput.

- Tools/workflows: Static lookup tables for GEMM algorithm selection (hipBLASLt/rocBLAS), sizing rules for hidden/head dimensions, vocabulary divisibility, batch×sequence constraints, minimizing tensor/expert parallel degrees.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable static tuning tables; predictable MoE balancing bands; adherence to divisibility rules to avoid kernel performance cliffs.

- Deploy small-MoE, top-1 routing for faster, cheaper inference

- Sector: software/SaaS, consumer apps, customer support

- What: Use the paper’s “MoE++” design (fine-grained experts, top-1 routing) to cut inference latency and cost versus larger top-k MoEs or dense models while maintaining quality.

- Tools/workflows: ZAYA1 router (MLP + EDA + PID balancing), removal of residual experts, lightweight residual scaling for stability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Router implementation quality; robust balancing across microbatches; minimal expert skew; availability of optimized top-1 dispatch kernels.

- Long-context training and inference using CCA + context parallelism

- Sector: education (paper assistants), legal (document analysis), healthcare (clinical notes), enterprise knowledge management

- What: Train/infer at 32k+ context with Compressed Convolutional Attention (CCA) to reduce prefill compute and KV cache size; pair with context parallelism for predictable scaling; use tree attention for long-context inference on xGMI.

- Tools/workflows: CCA (query/kv compression, conv blocks), ring/tree attention, RoPE base extension (10k→1M), staged context extension schedule, CP tuned to CCA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality CCA implementation; careful CP/message shaping to avoid xGMI bottlenecks; appropriate long-context datasets (books, legal briefs); scheduler changes for stability.

- Fault-tolerance and checkpoint reshaping at scale

- Sector: cloud/AI ops (MLOps, AIOps)

- What: Adopt the paper’s practical fault-tolerance setup and “reshape service” to switch parallelism regimes mid-run; accelerate checkpoint writes to reduce IO-induced training stalls.

- Tools/workflows: Checkpoint reshaping between ZeRO-1 and CP; accelerated PyTorch checkpoint IO; separate VPC fabric for storage; monitoring of iteration-time breakdown (compute vs comms vs IO).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reshape tooling integration with training framework; consistent optimizer state sharding; storage node bandwidth (200Gbps SmartNIC/DPUs).

- Domain fine-tuning on ZAYA1-base for math, coding, and reasoning

- Sector: software, finance (quant research), education (tutoring), robotics (task planning via language)

- What: Use ZAYA1-base (8.3B total / 760M active parameters) as a cost-effective base for domain-specific adapters/fine-tunes given its strong math, reasoning, and coding performance.

- Tools/workflows: LoRA/adapters atop MoE++ architecture; curated domain datasets; post-training SFT/RL; evaluation on domain benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensing/availability of ZAYA1-base; continued performance parity in downstream tasks; robust evaluation and safety guardrails.

- Procurement and policy guidance for vendor diversification

- Sector: public sector, national labs, enterprise procurement

- What: Use the case paper to inform AMD-based AI infrastructure purchases, stressing separated fabrics (training vs storage), per-GPU NICs, and rails-only topologies for cost-performance balance.

- Tools/workflows: RFP templates that include ROCm readiness, collective benchmark requirements, and cluster topology constraints; SLAs covering microbenchmark-backed throughput targets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Supply chain availability of MI300X/Pollara; organization’s ROCm readiness; staffing/training for AMD stack operations.

Long-Term Applications

- Automated hardware-aware model sizing toolchains

- Sector: software tooling, cloud AI platforms

- What: Productize the paper’s sizing rules into automated tools that generate model configs (hidden sizes, head dimensions, vocab divisibility) and static GEMM tuning tables for a given hardware/cluster topology.

- Tools/workflows: Integration with PyTorch, HIP/ROCm; autotuning services that learn optimal algorithms per shape; CI pipelines to refresh tuning as ROCm evolves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable APIs across ROCm releases; broad hardware coverage (AMD consumer/server GPUs); continuous benchmarking infrastructure.

- Standardized ROCm-first collective algorithms and CP libraries

- Sector: open-source ecosystems, HPC

- What: Develop collective algorithms purpose-built for xGMI constraints (full-node participation), plus tree-attention libraries optimized for AMD, making long-context inference robust without bespoke tuning.

- Tools/workflows: RCCL enhancements, tree-attention primitives adapted to AMD fabrics, message-pipelining strategies for Pollara saturation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; upstreaming into PyTorch/Transformers; cooperation with AMD on firmware/drivers.

- Cloud services offering managed AMD LLM training/inference

- Sector: cloud providers, AI platforms

- What: Commercial offerings that package MI300X clusters with Pollara networking, preloaded ROCm stacks, and “MoE++” recipes (CCA, ZAYA1 router, residual scaling, Muon) for turnkey training at scale.

- Tools/workflows: Managed Megatron-LM forks, Primus-based monitoring, prebuilt fault-tolerance/reshape services, curated long-context datasets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Market demand; SLAs around performance and availability; multi-tenant isolation for rails-only topologies.

- Energy-efficient, low-latency inference via small-MoE on edge/embedded

- Sector: robotics, IoT, autonomous systems

- What: Translate small-MoE top-1 routing and residual scaling to embedded AMD GPUs or future edge accelerators for real-time language reasoning and planning.

- Tools/workflows: Lightweight MoE dispatch kernels; quantization/post-training compression; latency-aware batching; cache management using CCA-like compression.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Edge hardware support for ROCm-like stacks; efficient MoE runtimes; memory bandwidth sufficiency on embedded devices.

- Long-context assistants for professional workflows

- Sector: legal, healthcare, finance, education

- What: Assistants that handle book-length inputs (case law, medical records, financial filings, textbooks) by leveraging CCA + CP + tree attention; integrate domain-specific fine-tuning and safety filtering.

- Tools/workflows: 32k–128k context models; retrieval-augmentation aligned with compressed KV caches; audit trails and explainability for regulated domains.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable long-context generalization; robust factuality and privacy controls; regulatory approvals in sensitive sectors.

- Muon-first optimizers for ultra-large-batch training at scale

- Sector: cloud/HPC AI training

- What: Broad adoption of second-order-inspired optimizers (e.g., Muon) with Newton–Schulz iterations to push batch sizes upward, improving utilization on very large clusters.

- Tools/workflows: Unified LR schemes across parameter types; optimizer-specific kernel fusion (matrix–matrix transpose); automated stability diagnostics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Continued evidence of convergence/stability; wide support in frameworks; handling optimizer state memory in extreme-scale runs.

- Vendor-neutral benchmark suites and procurement standards

- Sector: policy, standards bodies, enterprise IT

- What: Formalize collective/memory/GEMM microbenchmarks, iteration breakdown reporting, and rails-only topology best practices into vendor-neutral standards for AI infrastructure evaluation.

- Tools/workflows: Public benchmark repositories; certification programs; reporting templates for throughput/latency across message sizes and node counts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cross-vendor collaboration; updates as hardware/software stacks evolve; alignment with public-sector procurement needs.

- Cross-fabric algorithm co-design (compute–network aware models)

- Sector: research, hardware-software co-design

- What: New training/inference algorithms that explicitly optimize for the compute/memory/network rooflines (e.g., dynamic adjustments to top-k, expert widths, attention compression) based on real-time cluster telemetry.

- Tools/workflows: Runtime schedulers that adjust model knobs per iteration; telemetry-driven collective selection; adaptive fusion-buffer sizing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity monitoring; safe dynamic reconfiguration; guarantees on training stability.

- Open, reproducible AMD training curricula for academia

- Sector: academia, workforce development

- What: University courses and labs built around ROCm, RCCL, GEMM tuning, CP/tree attention, and MoE++ architectures to train the next generation of system-aware ML engineers.

- Tools/workflows: Teaching materials, open datasets, lab exercises replicating the paper’s methodology (HBM bandwidth measurement, collective scaling, sizing sweeps).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to AMD hardware or cloud credits; sustained community support; modular course content.

- Government and enterprise resilience through hardware diversification

- Sector: public sector, large enterprises

- What: Strategic diversification away from single-vendor dependence by establishing AMD-based AI centers of excellence, reducing supply-chain risk while maintaining competitive model performance.

- Tools/workflows: Programmatic investment, ROCm enablement training, standardized migration playbooks, benchmarking KPIs for continuous improvement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Budget and organizational will; vendor support; measurable ROI compared to incumbent stacks.

Glossary

- Activation memory: The portion of memory used to store intermediate activations during forward/backward passes, often a bottleneck at long contexts. Example: "The substantial reductions in attention FLOPs and activation memory that CCA provided also made context extension significantly easier than for alternative attention methods"

- All-gather: A collective communication operation that gathers data from all processes to all processes. Example: "microbenchmarks for all core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast)"

- All-reduce: A collective communication that aggregates values (e.g., sums) across processes and distributes the result back to all. Example: "microbenchmarks for all core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast)"

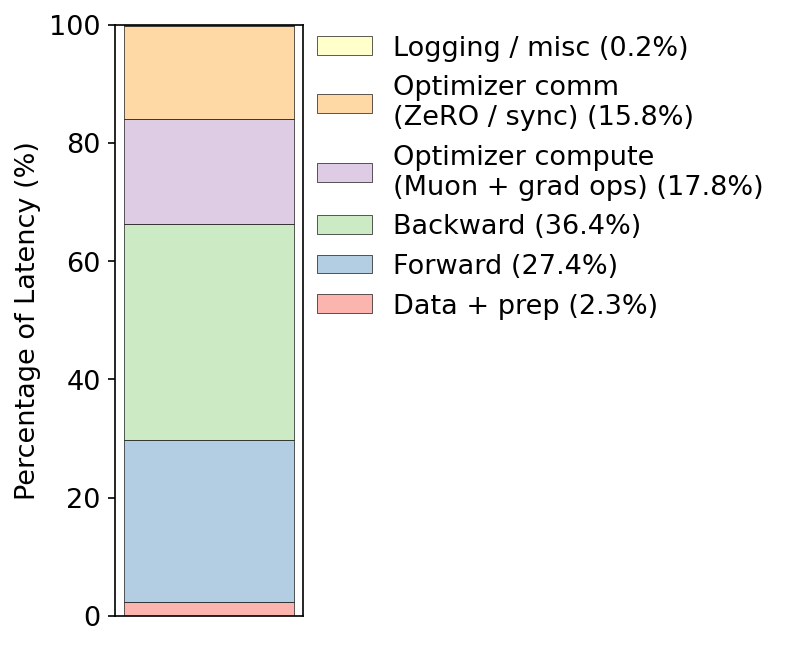

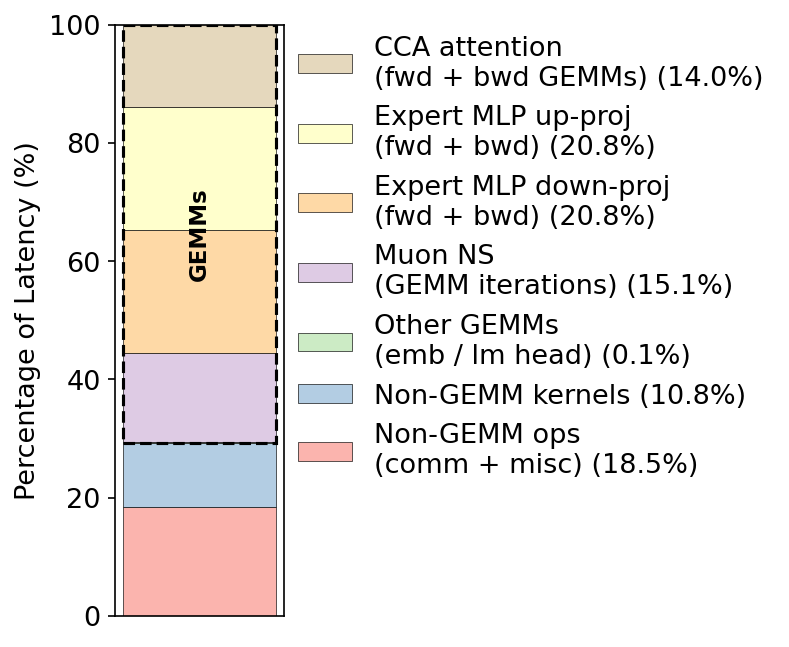

- BF16 (bfloat16): A 16-bit floating point format with a wide exponent for training efficiency on modern accelerators. Example: "Most of a model's iteration time is spent performing BF16 GEMM kernels (see Figure~\ref{fig:iter-breakdowns})."

- Broadcast: A collective operation that sends data from one process to all others. Example: "microbenchmarks for all core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast)"

- Bus bandwidth: The effective data transfer rate measured across a communication bus in benchmarks. Example: "(a) AllReduce Bus Bandwidth"

- CCA (Compressed Convolutional Attention): An attention mechanism that performs sequence-mixing in a compressed latent space to reduce compute and KV-cache size. Example: "Compressed Convolutional Attention (CCA) \citep{cca}, which executes attention in a compressed latent space to reduce both prefill compute and KV-cache size;"

- CCGQA: A combined/variant attention configuration that integrates compression with grouped-query techniques. Example: "For attention, we utilized CCGQA with a query compression rate of and a KV compression rate of ."

- Clos topology: A multi-stage, fat-tree network topology used for high-bandwidth, non-blocking switching. Example: "Instead of the classical Clos \citep{clos} topology, individual nodes are interconnected in a rails-only topology"

- Composable Kernel (CK): An AMD library of specialized GPU kernels for high-performance workloads. Example: "languages and libraries such as Heterogeneous-Compute Interface for Portability (HIP) \citep{amd_hip}, or Composable Kernel (CK) \citep{amd_composable_kernel}."

- Context parallelism (CP): A parallelization strategy that partitions the sequence/context across devices to scale long-context training/inference. Example: "Beyond the core model architecture, our training run used context parallelism (CP) (Section \ref{sec:context-parallelism}) tailored to CCA"

- Data parallelism: A distributed training approach that replicates the model across devices and splits batches of data among them. Example: "We pretrained solely using data-parallelism with the ZeRO-1 distributed optimizer"

- DPU (Data Processing Unit): A programmable network processor offloading networking/storage tasks from CPUs/GPUs. Example: "The VPC network connects each node via Pensando DSC SmartNIC/DPUs to a separate leaf--spine fabric"

- EDA (Exponential Depth Averaging): A mechanism that mixes routing information across layers with a learned coefficient to stabilize routing. Example: "using a mechanism we call Exponential Depth Averaging (EDA), since it represents an improvement to Depth-Weighted Averaging"

- Expert-parallelism: Parallelization that partitions Mixture-of-Experts across devices, routing tokens to different experts. Example: "such as expert- and tensor-parallelism \citep{gshard,megatron,anthony2024comms}"

- Flash Attention: An IO-aware attention algorithm optimized to reduce memory traffic and improve speed. Example: "Even IO-aware attention algorithms like Flash Attention \citep{dao2023flashattention2} are bottlenecked by the bandwidth of their HBM accesses until they reach higher sequence lengths."

- FLOPs: Floating-point operations, a measure of compute used or required by a model. Example: "CCA also improves training speed vs GQA and MLA and significantly reduces the FLOPs required for prefill"

- Fusion buffer: A buffer that aggregates many small tensors (e.g., gradients) into a larger message to improve communication efficiency. Example: "Distributed training frameworks such as ours provide a fusion buffer to batch gradient tensors into, and then communicate the fused buffer."

- GEMM (General Matrix Multiplication): A core linear algebra operation central to deep learning compute. Example: "boil down those ops into their component set of memory accesses and General Matrix Multiplications (GEMMs)"

- GQA (Grouped-Query Attention): An attention variant that shares key/value across groups of query heads to reduce memory and compute. Example: "such as MLA and GQA \citep{ainslie2023gqa,deepseekv3}"

- GPU-direct RDMA: A technology enabling direct GPU memory access over the network, reducing CPU involvement and latency. Example: "software that heavily relies upon GPU-direct RDMA."

- HBM (High Bandwidth Memory): On-package memory providing very high bandwidth for GPUs. Example: "MI300X GPUs have 192\,GB HBM"

- HIP (Heterogeneous-Compute Interface for Portability): AMD’s CUDA-like API for GPU programming on ROCm. Example: "languages and libraries such as Heterogeneous-Compute Interface for Portability (HIP) \citep{amd_hip}"

- hipBLASLt: A ROCm linear algebra backend providing tunable GEMM algorithms. Example: "ROCm provides multiple GEMM backends (rocBLAS and hipBLASLt), each containing many algorithms."

- InfinityFabric: AMD’s high-bandwidth intra-node GPU interconnect. Example: "Each node contains 8 MI300X GPUs interconnected with InfinityFabric."

- KV-cache: Cached key/value tensors from prior tokens to avoid recomputation during autoregressive inference. Example: "The KV-cache is a purely inference-time structure that stores the KV states of prior tokens so that they do not require recomputation for each subsequent token."

- Latency: The fixed time overhead before data transfer or computation proceeds, dominating small-message operations. Example: "(d) AllReduce Latency"

- Leaf–spine fabric: A two-tier data center network architecture providing predictable bandwidth and scale. Example: "to a separate leaf--spine fabric"

- Megatron-LM: A large-scale transformer training framework optimized for model/data parallelism. Example: "Our core training framework is a forked internal version of Megatron-LM adapted for the AMD stack."

- MLA: An attention variant referenced alongside GQA as a contemporary baseline. Example: "with MLA or GQA attention"

- MoE (Mixture-of-Experts): An architecture that routes tokens to specialized expert sub-networks to improve parameter efficiency. Example: "We report on the first large-scale mixture-of-experts (MoE) pretraining study on pure AMD hardware"

- MPI (Message Passing Interface): A standardized communication protocol for parallel computing. Example: "collective communication libraries (e.g. RCCL/NCCL/MPI) to design two-level collective algorithms"

- Muon optimizer: A second-order-inspired optimizer using matrix preconditioning with Newton–Schulz updates. Example: "ZAYA1-base is trained using the Muon optimizer \citep{jordan6muon}."

- NCCL (NVIDIA Collective Communications Library): NVIDIA’s library for multi-GPU collectives. Example: "collective communication libraries (e.g. RCCL/NCCL/MPI)"

- Newton–Schulz iterations: Iterative method for approximating matrix inverses used in Muon’s preconditioning. Example: "We performed five Newton-Schulz iterations per gradient step."

- NIC (Network Interface Card): Hardware that connects a device to a network fabric. Example: "Each GPU is assigned its own Pollara 400Gbps NIC"

- NVLink: NVIDIA’s high-bandwidth GPU interconnect. Example: "such as AMD InfinityFabric \citep{amd2024cdna3} or NVIDIA NVLINK \citep{nvidia_nvlink}."

- NVSwitch: A switch enabling all-to-all high-bandwidth connectivity among GPUs within a node. Example: "Most DL software makes the assumption of a switched intra-node topology like NVSwitch."

- PID controller: A feedback-control mechanism using proportional, integral, and derivative terms, adapted here for load balancing. Example: "inspired by proportionalâintegralâderivative (PID) \citep{aastrom2006pid} controllers from classical control theory."

- Pipeline parallelism: A model-parallel method that partitions layers across devices and pipelines microbatches. Example: "pipeline parallelism \citep{rajbhandari2020zero, gpipe}"

- Pollara interconnect: AMD Pensando high-speed network fabric for GPU clusters. Example: "utilizing both MI300X GPUs with Pollara interconnect."

- Prefill: The initial inference phase processing the prompt before generating the first token. Example: "We use the term prefill to denote the first phase of inference, where the model must first ingest the entire input sequence and generate the first token."

- Primus framework: AMD’s ROCm-based tooling and kernels for large-model training. Example: "we integrated and utilized several components from AMD's Primus framework \citep{primus2025}"

- Rails-only topology: A cost-efficient cluster network design trading path diversity for simpler wiring and aligned communication patterns. Example: "individual nodes are interconnected in a rails-only topology"

- RCCL (Radeon Collective Communications Library): AMD’s collective communication library analogous to NCCL. Example: "RCCL collective operations performance across InfinityFabric within a node."

- Reduce-scatter: A collective that reduces data across processes and scatters partitions of the result to each. Example: "microbenchmarks for all core collectives (all-reduce, reduce-scatter, all-gather, broadcast)"

- Residual scaling: Learned per-layer scaling and biasing of the residual stream to control information flow. Example: "The final architectural innovation in ZAYA1-base is residual scaling."

- Ring attention: A sequence-parallel attention algorithm using ring-style communication. Example: "ZeRO-1 + context parallelism (ring attention \citep{liu2023ring}) when scaling context up to 32768."

- RMSnorm: A normalization layer that scales activations by their root-mean-square without centering. Example: "a fused RMSnorm/LN kernel"

- RoPE (Rotary Positional Embeddings): A positional encoding scheme rotating query/key vectors by position-dependent phases. Example: "We applied RoPE \citep{su2023rotary} to half the channels in each head, leaving the other half without position embeddings."

- Roofline model: A performance model relating compute and memory bandwidth limits to identify bottlenecks. Example: "The crossover point is dependent on the particular GPU's roofline"

- Sharded optimizer states: Partitioning optimizer state tensors across devices to reduce memory usage. Example: "with the ZeRO-1 distributed optimizer, where only the optimizer states are sharded."

- SmartNIC: A NIC with onboard processing (e.g., offloads), often used for storage/management traffic isolation. Example: "The VPC network connects each node via Pensando DSC SmartNIC/DPUs to a separate leaf--spine fabric"

- Tensor-parallelism: Splitting tensor dimensions of layers across devices to increase model size without replication. Example: "such as expert- and tensor-parallelism \citep{gshard,megatron,anthony2024comms}"

- Top-k routing: Selecting the k highest-scoring experts per token in MoE routers. Example: "The scores are then used to select the chosen expert via top-k operation:"

- Tree attention: A communication-efficient attention method organizing exchanges in a tree rather than a ring. Example: "Long-context inference relies heavily on tree attention \citep{shyam2024tree} to avoid the bandwidth bottleneck of xGMI."

- Two-level collective algorithms: Collective strategies that exploit fast intra-node links to improve inter-node scaling. Example: "collective communication libraries (e.g. RCCL/NCCL/MPI) to design two-level collective algorithms that rely heavily on the intra-node fabric"

- VPC network: A logically isolated network used here for storage and management traffic. Example: "while a VPC network manages dataset I/O, checkpoints, and cluster management."

- xGMI: AMD’s GPU-to-GPU interconnect protocol used within InfinityFabric for intra-node communication. Example: "AMD's InfinityFabric uses xGMI \citep{xgmi}, which requires all GPUs participate in a given collective operation to achieve full bandwidth"

- ZeRO-1: The first stage of the Zero Redundancy Optimizer that shards optimizer states across data-parallel ranks. Example: "our parallelism topology for ZAYA1 is just the ZeRO-1 distributed optimizer during initial pretraining at 4096 sequence length"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.