Self-Improving Pretraining: using post-trained models to pretrain better models

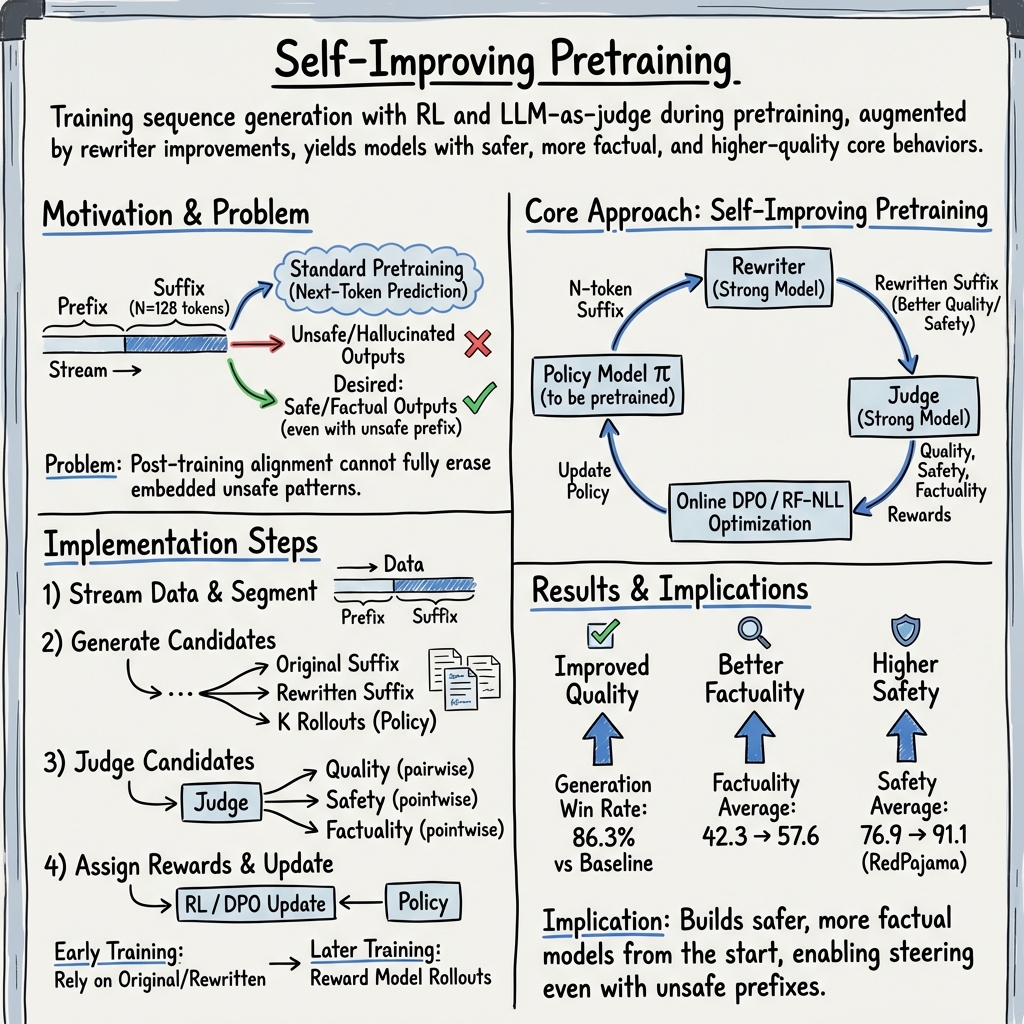

Abstract: Ensuring safety, factuality and overall quality in the generations of LLMs is a critical challenge, especially as these models are increasingly deployed in real-world applications. The prevailing approach to addressing these issues involves collecting expensive, carefully curated datasets and applying multiple stages of fine-tuning and alignment. However, even this complex pipeline cannot guarantee the correction of patterns learned during pretraining. Therefore, addressing these issues during pretraining is crucial, as it shapes a model's core behaviors and prevents unsafe or hallucinated outputs from becoming deeply embedded. To tackle this issue, we introduce a new pretraining method that streams documents and uses reinforcement learning (RL) to improve the next K generated tokens at each step. A strong, post-trained model judges candidate generations -- including model rollouts, the original suffix, and a rewritten suffix -- for quality, safety, and factuality. Early in training, the process relies on the original and rewritten suffixes; as the model improves, RL rewards high-quality rollouts. This approach builds higher quality, safer, and more factual models from the ground up. In experiments, our method gives 36.2% and 18.5% relative improvements over standard pretraining in terms of factuality and safety, and up to 86.3% win rate improvements in overall generation quality.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching LLMs (like chatbots) to write safe, accurate, and high‑quality text from the very start of their training. Instead of fixing problems later, the authors show how to build good habits during pretraining by letting a strong “teacher” model guide and judge the learning process.

Key Questions

The researchers asked:

- Can we train a model to avoid unsafe or made‑up (hallucinated) content during pretraining—not just later?

- Can a stronger, already well‑trained model help a new model learn better habits as it grows?

- Will this approach make the new model produce higher quality, safer, and more factual text?

How the Method Works (in simple terms)

Think of training a model like teaching someone to write stories or answers.

- Prefix and suffix: The “prefix” is the part of the text you already have. The “suffix” is the next short chunk of text (like the next few sentences) the model needs to write.

- Candidates: At each step, the model considers three possible endings for the prefix: 1) The original ending from the training data (the original suffix). 2) A “rewrite” made by a strong, experienced model (the teacher) that tries to make the ending safer and higher quality. 3) One or more endings drafted by the model being trained (its own rollouts).

- The judge: A strong model acts like a judge and scores each candidate for quality, safety, and factual accuracy. It picks the best one and gives feedback.

- Reinforcement learning (RL): This process is like practice with rewards. If the model’s own draft is good, it gets rewarded and learns to make more endings like that. If it’s bad, the judge points it away from that choice and toward better examples.

- Early vs. later training: Early on, the new model’s drafts are weak, so it mostly learns from the original text and the teacher’s rewrites. Later, as it improves, it starts learning more from its own high‑quality drafts—because it can produce good ones and get rewarded for them.

- Why “sequence pretraining” matters: Traditional pretraining teaches the model to predict the next word. This paper instead teaches it to write a short, coherent chunk of text (a sequence). That’s closer to what we want in real use: not just the next word, but a good, safe, factual continuation.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here are the key results, explained in everyday terms:

- Better quality writing: The new training method made the model’s writing noticeably better. In one setup, it beat the standard approach in head‑to‑head comparisons by up to about 86% (a big win rate improvement).

- Fewer made‑up facts (hallucinations): The model became more factually accurate. The paper reports about a 36% relative improvement in factuality over regular pretraining.

- Safer content: The model produced safer text, with about an 18% relative improvement in safety compared to standard pretraining.

- Works both ways: The method helps whether you start from scratch or keep training an existing model (continual pretraining). From scratch, it improved both quality and safety a lot.

Why this matters:

- It builds good behavior early, so problems don’t become deeply embedded in the model.

- It trains the model to “steer away” from unsafe prompts by choosing safe endings even when the earlier text is risky.

- It reduces the need for complicated fixes later, because the model grows up with better habits.

Implications and Impact

This approach could change how we train LLMs:

- Safer from the ground up: Models learn to avoid harmful or untrue content during pretraining, not just after.

- More trustworthy: By using a strong judge and editor (the teacher model) to guide learning, new models become more reliable for everyday use—like tutoring, customer support, or creative writing.

- Practical and scalable: Instead of relying only on expensive, perfectly clean datasets, the model learns to handle messy, real‑world inputs and still produce safe, accurate, high‑quality text.

In short, the paper shows a promising way to raise “better‑behaved” models by using a strong mentor during pretraining, helping them write well, stay safe, and stick to the facts.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper that future work could address:

- Dependence on LLM-as-judge: robustness and bias

- How robust are results to judge model choice, calibration, and biases (e.g., GPT-OSS-120B vs. fine-tuned Llama3.1-8B)? What happens with weaker/cheaper judges or ensembles?

- To what extent do models learn to optimize judge idiosyncrasies (Goodharting/reward hacking) rather than true safety/factuality/quality?

- Human evaluation and external validation

- Lack of large-scale human preference/safety assessments to validate LLM-judged improvements in quality, safety, and factuality.

- No inter-rater reliability or construct validity studies comparing judge decisions to expert human labels across domains.

- Generalization beyond English web corpora

- Unclear performance for non-English languages, low-resource domains, code/math, or multimodal inputs.

- No tests on out-of-distribution domains or specialized safety contexts (e.g., bio, cyber, finance).

- Scaling laws and compute–performance trade-offs

- How does the approach scale with policy size (beyond 1.4B), judge size, number of rollouts K, and dataset size?

- Comprehensive cost–benefit analysis vs. standard pretraining is missing (throughput, GPU hours, latency, memory, carbon footprint).

- Long-context and sequence length sensitivity

- Effects of suffix length N=128 and chunking strategy on long-range coherence, reasoning, and safety not explored.

- No analysis of boundary handling (document boundaries, sliding windows, partial contexts) and its impact on training/evals.

- Scheduling and curriculum for rollouts vs. suffix/rewrites

- No principled schedule for when/ how fast to shift weight from original/rewritten suffixes to policy rollouts.

- Open question: can adaptive curricula (based on rollout win rates or confidence) outperform fixed schedules?

- Reward shaping and multi-objective trade-offs

- The method averages or combines safety, factuality, and quality signals, but does not explore weighting, calibration, or Pareto trade-offs.

- Joint multi-objective self-improving pretraining (optimizing all objectives simultaneously) is not investigated.

- RL objective design and stability

- Limited to online DPO and RF-NLL; no comparison to alternative sequence-level RL methods (e.g., GRPO, PPO variants) under identical constraints.

- KL control, regularization against drift, variance reduction, and credit assignment strategies are not specified or ablated.

- Pairwise judging complexity and approximations

- Pairwise O(K2) judging is expensive; pivot-based approximations are mentioned but not systematically evaluated for bias/efficiency/accuracy trade-offs.

- Unclear how noisy or inconsistent pairwise rankings affect DPO convergence.

- Rewriter fidelity and semantic preservation

- Safety-focused rewrites for unsafe suffixes may alter semantics; there’s no measurement of meaning preservation or factual consistency relative to the prefix.

- Token overlap analyses do not guarantee preservation of key facts or intent; need semantic equivalence metrics and audits.

- Data contamination and leakage risks

- Although non-overlap subsets are stated, risks remain that the judge, rewriter, and policy share distributional artifacts or near-duplicates.

- No auditing for memorization or privacy leakage, especially given explicit copying of “safe” suffixes.

- Safety scope and robustness

- Safety categories and taxonomies (e.g., toxicity vs. jailbreaks, targeted harms, bias/fairness) are not clearly delineated; robustness to adversarial prompts or jailbreaks is untested.

- Cross-cultural safety norms and context-dependent harms are not evaluated.

- Factuality ground-truthing

- Factuality judging relies on “human continuation” or judge world knowledge; no guarantee of correctness or source-grounding beyond provided references.

- Lack of evaluation with retrieval-grounded factuality or citation verification tasks.

- Over-optimization to judge-driven evaluations

- Training and most evaluations rely on LLM judges (sometimes the same family/prompt style), risking circularity and overfitting to judge preferences.

- Need for “judge diversity” stress tests and evaluations with orthogonal metrics (e.g., reference-based BLEU/ROUGE for relevant tasks, human audits).

- Impact on general capabilities and potential regressions

- While some standard benchmarks improve, there is limited analysis of trade-offs (e.g., creativity, diversity, calibration, reasoning depth) and no perplexity reporting.

- Catastrophic forgetting is only partially addressed; more granular capability auditing is needed.

- Reward calibration and uncertainty

- Discrete labels (e.g., No/Possible/Definite hallucination mapped to 1/0.5/0) are heuristic; no calibration analysis or uncertainty-aware rewards.

- Sensitivity to prompt design, temperature, and seed variance is noted but not comprehensively quantified.

- Optimal rollout count and sampling strategy

- Effects of K>16, decoding policies (e.g., nucleus vs. temperature schedules), and re-ranking are not explored as a cost–quality frontier.

- No adaptive strategy to allocate more rollouts for hard examples based on judge confidence.

- Iterative “self-improving” cycles

- The paper assumes a strong post-trained model; it does not demonstrate full iterative cycles where a newly trained model becomes the next judge/rewriter and improves further.

- Stability and convergence properties across cycles are unknown.

- Integration with standard pretraining objectives

- How to mix next-token prediction with sequence-level RL at scale (e.g., joint optimization, alternating schedules) is not studied.

- Effects on language modeling metrics (perplexity), calibration, and downstream fine-tuning cost reductions remain unmeasured.

- Robustness to noisy or adversarial judges

- No tests of the method under noisy, biased, or adversarial judge prompts, or under judge drift across time/domains.

- LLM-judge prompting and instruction variability are not stress-tested for brittleness.

- Ethical and safety process considerations

- The approach deliberately ingests unsafe prefixes; operator safety, red-teaming protocols, and governance for filtering/rewriting are not described.

- Legal and copyright implications of copying/rewriting data (especially “safe copying”) are not discussed.

- Reproducibility and missing implementation details

- Key training details for DPO (e.g., beta/temperature of the preference model, KL constraints), normalization of rewards, and exact mixing ratios are not fully specified.

- Variance across training seeds and confidence intervals on main results are not reported.

- Benchmarks and coverage

- Safety and factuality benchmarks are limited; richer and more recent suites (e.g., jailbreak robustness, bias/fairness audits, red-teaming benchmarks) are not included.

- Lack of evaluation on interactive, tool-using, or retrieval-augmented settings where safety and factuality are critical.

- Practical deployment questions

- Inference-time behavior under different decoding settings (greedy vs. sampled) is unreported; safety/quality under user-facing sampling is unknown.

- Operational costs and engineering complexity (e.g., streaming RL infrastructure in pretraining, judge latency) are not quantified.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete ways the paper’s “Self-Improving Pretraining” (SIP)—sequence-level pretraining with a judge and rewriter—can be put to use now, along with sectors, potential tools/workflows, and feasibility notes.

- Safer general-purpose chatbots “out of the box”

- Sectors: consumer AI; customer support; gaming; social platforms

- What: Pretrain new or existing small/mid models to steer from unsafe user prompts (prefixes) to safe, coherent continuations (suffixes), reducing reliance on post-training-only alignment.

- Tools/workflows: Judge-as-a-Service (quality/safety/factuality); suffix rewriter module; online DPO or reward-filtered NLL in the pretraining loop; rollout sampling orchestration

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to a strong and unbiased judge model; compute to support multiple rollouts and pairwise judgments; clear safety policies for prompts and outputs

- Enterprise continual pretraining on internal corpora with safety/factuality baked in

- Sectors: finance; healthcare; legal; enterprise software; telco

- What: Stream internal documents and emails, chunk into prefixes/suffixes, and enforce compliance via judges during pretraining to produce domain-aligned, safer, more factual foundation models for internal use.

- Tools/workflows: “Continuous Pretraining Orchestrator” (document streaming, chunking, rollout sampling, judge evaluation); on-prem or VPC judges for sensitive data

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy and data governance; domain-calibrated judges; sufficient compute; legal approval for model training on internal data

- Higher-fidelity summarization and QA systems with reduced hallucination

- Sectors: media; research; legal; enterprise knowledge management

- What: Pretrain with factuality judges to improve adherence to ground truth and reduce fabricated content in summarization or QA tasks.

- Tools/workflows: Factuality-judged pretraining setting using reference texts; integration with QA/summarization pipelines

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong factuality judges and reference-rich domains; judge prompt quality; risk of judge bias across topics and languages

- Safer autocomplete and writing assistants in productivity suites

- Sectors: productivity software; email/calendars; document editors

- What: Train autocomplete models that avoid toxic or policy-violating suggestions while maintaining coherence and helpfulness.

- Tools/workflows: SIP with safety/quality judges; small rollouts at training time; deployment via greedy decoding + runtime guardrails

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong safety judge tuned to enterprise policies; minimal latency budgets for training-time rollouts

- Data cleaning and augmentation through suffix rewriting

- Sectors: data vendors; MLOps; annotation services

- What: Improve low-quality or unsafe corpus segments by rewriting only suffixes (keeping original context), creating higher-quality pretraining sets without deleting challenging contexts.

- Tools/workflows: Batch rewrite pipeline; token-overlap tracking and safety scoring; audit logs of rewritten segments

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensing and IP rights for transformation; quality assurance on rewrites to avoid distribution drift; reproducible judge decisions

- Compliance-aware copilots and assistants

- Sectors: finance; pharma; insurance; government

- What: Pretrain so models consistently steer unsafe or non-compliant prompts to compliant responses, improving reliability before post-training.

- Tools/workflows: Compliance-tuned judges (e.g., FINRA, HIPAA policy templates); SIP loop with unsafe prefixes mined from real corpora

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory interpretation captured in judge prompts; continuous monitoring for drift; legal oversight

- More robust code assistants (quality and factuality over hallucinated APIs)

- Sectors: software engineering; DevOps

- What: Use quality/factuality judges (potentially augmented with test execution or static analysis) during pretraining to discourage hallucinated functions and encourage coherent, compilable code.

- Tools/workflows: Code-aware judges; integration with unit-test generation as “factuality oracle”; DPO over multiple candidate continuations

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable automated tests or static checkers as proxy judges; language/toolchain coverage; risk of overfitting to test heuristics

- Judgment harnesses for offline A/B evaluation and model selection

- Sectors: MLOps; evaluation platforms

- What: Use the paper’s pairwise- and pointwise-judging prompts and workflows to automate win-rate comparisons during model iteration.

- Tools/workflows: Pairwise comparison harness; seed-averaged judgments; DPO-ready preference logs

- Assumptions/dependencies: Judge stability under temperature/seed; calibration across tasks and domains

- Synthetic training of judge/rewrite models for scarce domains

- Sectors: AI research; specialized industries (aviation, energy)

- What: Produce synthetic corrupted/unsafe samples to train domain-specific judges and rewriters when labeled data is scarce.

- Tools/workflows: GRPO/SFT pipelines for judge/rewriter training; controlled corruption prompts; multi-seed consensus labeling

- Assumptions/dependencies: Validity of synthetic data as a proxy; careful prompt engineering; detecting failure modes of synthetic corruptions

- Multilingual safety and quality pretraining (where judges exist)

- Sectors: global platforms; customer service; government services

- What: Apply SIP in supported languages to reduce toxicity and improve coherence/factuality across locales.

- Tools/workflows: Multilingual judge prompts; language-aware chunking; language-specific suffix rewriting

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability and reliability of multilingual judges; generalization across dialects; cultural policy nuance

- Lightweight on-device models distilled with judged rollouts

- Sectors: mobile; edge AI; embedded systems

- What: Train small models using SIP with a large cloud judge, then distill to on-device targets with improved safety/factual biases.

- Tools/workflows: Cloud-judged rollout generation + distillation; privacy-preserving data flows

- Assumptions/dependencies: Connectivity during training; privacy constraints; distillation retaining safety/factuality

- Safer content moderation augmentation

- Sectors: social media; UGC platforms; marketplaces

- What: Generate safe continuations or “deflections” for unsafe contexts (e.g., counseling instead of instructing harm), improving moderator tools.

- Tools/workflows: Rewriter-driven safe continuations; audit and escalation workflows; integration with existing moderation queues

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear platform policy; human-in-the-loop escalation; transparency for affected users

Long-Term Applications

The following rely on further research, scaling, or infrastructure but naturally extend from the paper’s approach.

- Fully automated self-improvement cycles with minimal human supervision

- Sectors: AI labs; foundation model providers

- What: Iteratively train next-generation models using prior post-trained judges and rewriters at scale, closing the loop for continual quality/safety/factuality gains.

- Tools/workflows: Auto-judge/auto-rewriter orchestration; reward model ensembles; periodic human audits

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust guardrails to prevent reward hacking; judge drift detection; compute scaling and cost control

- Regulated assurance frameworks that require pretraining-time safety gates

- Sectors: policy/regulatory; public sector; critical infrastructure

- What: Codify “safety-at-pretraining” as a requirement for high-stakes deployments (e.g., healthcare, finance), with auditing of reward distributions and judge rationales.

- Tools/workflows: Compliance reporting APIs; judge decision logs; reproducible seeds; third-party auditing

- Assumptions/dependencies: Policy consensus; transparency on judge models; standards for acceptable reward models

- High-stakes domain models with domain-expert judges

- Sectors: healthcare; law; aviation; energy

- What: Pretrain with judges grounded in verified guidelines, ontologies, and expert rules (e.g., clinical practice guidelines, legal statutes), aiming for lower-risk outputs.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-tuned judges (potentially hybrid LLM + rule engines); curated unsafe-prefix corpora; domain-specific factuality scoring

- Assumptions/dependencies: Validated domain references; liability frameworks; rigorous post-deployment monitoring

- Continual learning from live data streams under strict privacy and safety

- Sectors: SaaS; enterprise; consumer platforms

- What: SIP applied to streaming user interactions/logs to adapt to concept drift, with judges preventing memorization of sensitive data and unsafe behaviors.

- Tools/workflows: Privacy-preserving data pipelines; differential privacy; red-team reward tests; rollback mechanisms

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal consent; secure data infrastructure; reliable online training stability

- Cross-modal extension (vision, speech, robotics) for sequence-level safety

- Sectors: robotics; autonomous systems; multimodal assistants

- What: Apply judge-based sequence evaluation to action plans, voice responses, or image captions, improving safe behavior in embodied or multimodal systems.

- Tools/workflows: Modality-specific judges (e.g., safety checkers, simulators, test benches); rollout sampling for trajectories

- Assumptions/dependencies: Building reliable non-text judges; real-world evaluation; sample efficiency in long-horizon tasks

- Hardware/software co-design for judged rollouts at scale

- Sectors: AI infrastructure; cloud providers

- What: Accelerate batched rollouts and pairwise judging (e.g., memory-efficient sampling, low-latency comparison kernels) to make SIP routine for large models.

- Tools/workflows: Inference-time sampling accelerators; judge-serving frameworks; caching/replay buffers for off-policy learning

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor support; cost/benefit at scale; eco-efficiency concerns

- Marketplace of judges and rewriters with standardized APIs and benchmarks

- Sectors: AI tooling; platforms; open-source ecosystems

- What: Pluggable, audited judge and rewriter services specialized by task/sector, with reproducible benchmarks and calibration suites.

- Tools/workflows: API standards (scoring schemas, confidence); leaderboard-based evaluations; bias/fairness audits

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interoperability; trust in third-party judges; governance for conflicts of interest

- Auditable CoT traces for governance and incident analysis

- Sectors: governance; risk; compliance; forensics

- What: Use judge reasoning traces (CoT) as part of audit trails, enabling explainability, bias analysis, and post-incident reviews.

- Tools/workflows: Secure log retention; CoT summarization; anomaly detection on reward/decision distributions

- Assumptions/dependencies: Policies for CoT storage; privacy and legal constraints; robustness against prompt injection

- Education/tutoring systems with pedagogical judges

- Sectors: edtech; lifelong learning

- What: Pretrain tutors that maintain factual accuracy and age-appropriate safety standards while adapting to student inputs.

- Tools/workflows: Curriculum-aligned judges; adaptive rewrite policies for misconceptions; formative assessment integration

- Assumptions/dependencies: Pedagogical validity; bias and equity considerations; parental/educator oversight

- Reliable code generation with executable-grounded judges

- Sectors: software engineering; DevSecOps

- What: Couple judges with unit tests, static analyzers, and sandboxed execution to provide grounded feedback during pretraining.

- Tools/workflows: Test synthesis pipelines; coverage-based reward shaping; security scanners as safety judges

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality of auto-generated tests; avoidance of over-optimization to tests; secure sandboxing

Notes on Feasibility, Risks, and Dependencies

- Judge quality and bias: The approach depends heavily on the availability and reliability of strong judges (e.g., Llama3-class or larger). Biases or blind spots will propagate into the trained policy. Ensembles and periodic human audits are advisable.

- Compute and cost: Online rollouts and pairwise judgments are compute-intensive. Scaling strategies (e.g., fewer rollouts early, pivot-based comparisons, caching) and hardware co-optimizations reduce cost.

- Domain transfer: Judges must be calibrated to the domain (e.g., clinical, legal). General-purpose judges may mis-score domain-appropriate content.

- Legal and IP: Rewriting or transforming training corpora must respect licenses; internal data use requires rigorous privacy compliance.

- Stability of training: RL methods can cause collapse without proper candidate pools and reward shaping. The paper’s results favor online DPO with multiple rollouts and robust judges.

- Evaluation dependence: Reported gains partly rely on judge-based evaluations (e.g., GPT-OSS-120B), which can align with training judges. Independent human or task-based evaluations remain crucial.

- Safety is not solved by pretraining alone: Downstream alignment and guardrails are still needed, but SIP reduces the burden by baking core behaviors into the base model.

Glossary

- Ablation study: A controlled experiment that removes or varies components to assess their contribution to overall performance. "We provide a detailed analysis and ablation studies of the optimization strategies that contribute to these wins."

- Alignment: Post-training methods that shape model behavior to adhere to desired norms, safety, and instructions. "applying multiple stages of fine-tuning and alignment."

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): An approach where a model generates intermediate reasoning steps before giving a final answer or judgment. "LLM judges become more robust and effective when they generate their own Chain-of-Thought (CoT) analyses before producing final judgments"

- Continual pretraining: Further pretraining of a model on new data or tasks after initial pretraining, to adapt or extend capabilities. "in the latter continual pretraining setting, we obtain win rates in generation quality of up to 86.3% over the standard pretraining baseline"

- Continued pretraining: Ongoing pretraining from an existing checkpoint (as opposed to training from scratch). "continued pretraining setting"

- Cosine learning rate: A schedule where the learning rate follows a cosine curve over training steps, often decaying smoothly. "with cosine learning rate , min ratio $0.1$"

- DPO (Direct Preference Optimization): A preference-based RL objective that optimizes a policy directly from chosen vs. rejected examples without an explicit reward model. "In our experiments we consider both online DPO"

- Factuality: The degree to which generated content is accurate and consistent with known facts or references. "relative improvements over standard pretraining in terms of factuality and safety"

- From-scratch pretraining: Training a model starting from randomly initialized weights rather than from a pretrained checkpoint. "To pretrain from scratch, we use a similar setup"

- Greedy generations: Decoding by always selecting the most probable next token at each step, without sampling. "For the policy model we use greedy generations."

- GRPO: A reinforcement learning algorithm that optimizes a policy using relative preferences across groups of sampled outputs. "we use GRPO \citep{shao2024deepseekmath} as our optimization algorithm"

- Hallucination: Model outputs that are fabricated or inconsistent with the input, references, or real-world facts. "The judge also detects other quality issues such as hallucination, improving those as well by rewarding better rollouts."

- LLM judge: A LLM used to evaluate the quality, safety, or factuality of candidate outputs. "LLM judges become more robust and effective"

- Model collapse: A failure mode where a model degenerates to low-diversity, low-quality outputs (e.g., repetitive or meaningless text). "which is expected (i.e., model collapse)."

- Negative log-likelihood (NLL): A standard supervised learning objective that maximizes the likelihood of target tokens by minimizing their negative log probability. "For RF-NLL we simply take the highest scoring to conduct an NLL update."

- Off-policy: Learning from data not generated by the current policy, enabling use of external or historic samples. "DPO is an off-policy algorithm that allows learning from sequences not generated from the current policy"

- Online DPO: Applying Direct Preference Optimization during training while continuously generating and comparing candidates. "Self-Improving Pretraining models are trained with online DPO"

- Pairwise judgment: An evaluation setup where two candidate outputs are compared and a judge selects the better one. "For the quality judge, this is a pairwise judgment given two candidate responses"

- Pivot candidate: A fixed reference candidate used to compare against multiple other candidates in pairwise evaluations. "using a single pivot candidate for pairwise comparisons"

- Pointwise judgment: An evaluation setup where a single candidate is scored independently, rather than compared against another. "For the factuality judge, this is a pointwise judgment given one candidate response"

- Policy model: The model being trained to generate outputs; in RL, the policy maps contexts to action distributions (token selections). "We train our policy model using the sequence pretraining task"

- Post-training: Stages after initial pretraining (e.g., instruction tuning, alignment) that refine the model’s behavior. "The standard approach tries to course correct for these issues during post-training"

- Prefix-conditioned suffix generation: Generating a fixed-length continuation (suffix) conditioned on the preceding context (prefix). "The {\em sequence} pretraining task: prefix-conditioned suffix generation"

- RF-NLL (Reward-Filtered Negative Log-Likelihood): Training by selecting or weighting examples based on a reward signal and then applying NLL updates to the chosen ones. "reward-filtered negative log-likelihood training (RF-NLL)"

- Rollout: A model-generated candidate continuation sampled from the current policy for evaluation and learning. "N rollouts from the current policy"

- Safety: The property of avoiding harmful, toxic, biased, or otherwise unsafe outputs. "Ensuring safety, factuality and overall quality in the generations of LLMs is a critical challenge"

- Self-Improving Pretraining: A method where a strong post-trained model rewrites and judges training targets so the next model learns safer, higher-quality, more factual sequences during pretraining. "Self-Improving Pretraining"

- SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning): Refining a model via supervised learning on curated input-output pairs. "Unlike SFT, GRPO does not require generating high-quality synthetic CoT data"

- Suffix judge: A judge that scores possible suffixes (original, rewritten, or rollouts) to provide rewards for training. "Suffix judge safety prompt."

- Suffix rewriter: A model that rewrites a suffix to improve quality or safety while keeping the original prefix context. "Suffix Rewriter"

- Teacher model: A stronger, fixed model used to provide rewritten targets and/or judgments for training another model. "We consider using this fixed teacher model in two ways: as a {\em rewriter} and as a {\em judge}."

- Temperature (sampling): A sampling parameter controlling randomness in token selection; higher temperature yields more diverse outputs. "with 16 generations per prompt under temperature "

- Token overlap: A similarity metric measuring how many tokens two sequences share, used here to assess how much a rewrite changes the original. "Token Overlap in Suffix Rewriter Validation on RedPajama Dataset."

- Top-p sampling: Nucleus sampling that restricts token selection to the smallest set whose cumulative probability exceeds p. "with 16 generations per prompt under temperature and "

- Win rate: The fraction of pairwise comparisons where a model’s output is judged better than a baseline. "win rate of 86.3% over the baseline generations"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.