PointWorld: Scaling 3D World Models for In-The-Wild Robotic Manipulation

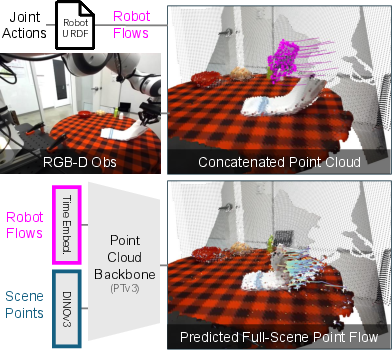

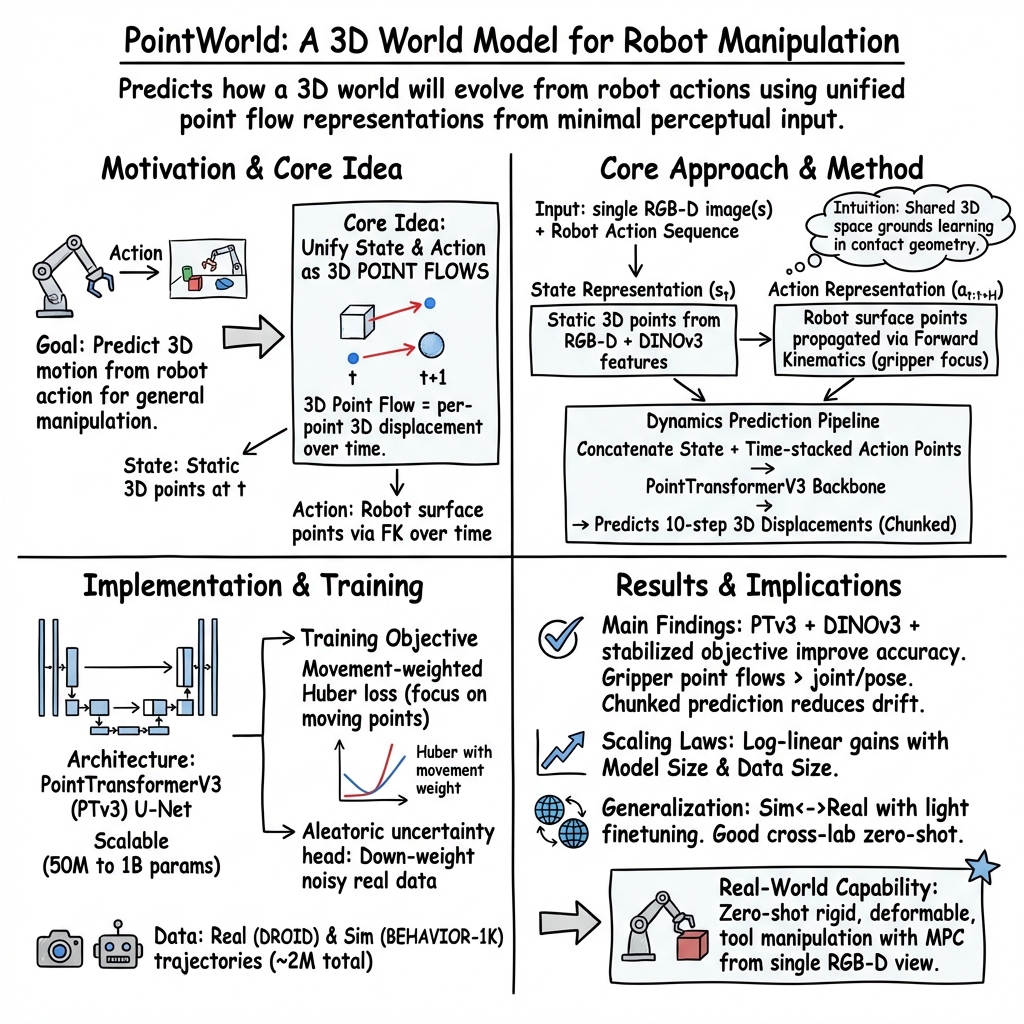

Abstract: Humans anticipate, from a glance and a contemplated action of their bodies, how the 3D world will respond, a capability that is equally vital for robotic manipulation. We introduce PointWorld, a large pre-trained 3D world model that unifies state and action in a shared 3D space as 3D point flows: given one or few RGB-D images and a sequence of low-level robot action commands, PointWorld forecasts per-pixel displacements in 3D that respond to the given actions. By representing actions as 3D point flows instead of embodiment-specific action spaces (e.g., joint positions), this formulation directly conditions on physical geometries of robots while seamlessly integrating learning across embodiments. To train our 3D world model, we curate a large-scale dataset spanning real and simulated robotic manipulation in open-world environments, enabled by recent advances in 3D vision and simulated environments, totaling about 2M trajectories and 500 hours across a single-arm Franka and a bimanual humanoid. Through rigorous, large-scale empirical studies of backbones, action representations, learning objectives, partial observability, data mixtures, domain transfers, and scaling, we distill design principles for large-scale 3D world modeling. With a real-time (0.1s) inference speed, PointWorld can be efficiently integrated in the model-predictive control (MPC) framework for manipulation. We demonstrate that a single pre-trained checkpoint enables a real-world Franka robot to perform rigid-body pushing, deformable and articulated object manipulation, and tool use, without requiring any demonstrations or post-training and all from a single image captured in-the-wild. Project website at https://point-world.github.io/.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces PointWorld, a big “world model” for robots. In simple terms, it’s a brain that helps a robot look at a scene once, think about a possible movement, and then predict how every part of the 3D scene will move in response. It does this in real time and works in messy, real-world places (like kitchens or offices), not just clean labs.

What questions were the researchers trying to answer?

- Can we teach a single model to predict how the 3D world changes when a robot moves, even in new, everyday environments?

- Can we describe both what the robot sees and what it plans to do in the same simple 3D way, so the model works across different robot types?

- What design choices (data, model architecture, training tricks) make these 3D world models accurate, fast, and scalable?

- Can this model help a real robot act (push things, use tools, move flexible or jointed objects) from just one RGB-D image without extra training?

How did they do it? (Methods explained simply)

Think of the world as a cloud of tiny dots in 3D, where each dot marks part of a surface you can see (like a table, a cup, or a cloth). This is called a 3D point cloud. The robot also has dots on its grippers (the parts that touch things). When the robot plans a motion, those gripper dots trace paths through space.

- One shared language: 3D dot motion

- State (what the world looks like): a 3D dot cloud built from a single RGB-D image (an image with depth, like what a phone or Kinect can capture).

- Action (what the robot will do): the robot’s future gripper movements, also as dots moving in 3D.

- The model’s job: given the starting dots (the scene) and the planned robot dot paths (the action), predict how every scene dot will move over the next short time window (around 1 second, split into 10 small steps).

- Why this is clever

- It focuses on geometry and contact, not just pretty pictures. That’s what matters for physics (like pushing, grasping, folding).

- Actions are “embodiment-agnostic,” which means they don’t depend on a specific robot’s joint angles. Describing actions as 3D gripper dot paths lets the same model learn from many different robots and still understand what “make contact here and move like this” means.

- The model

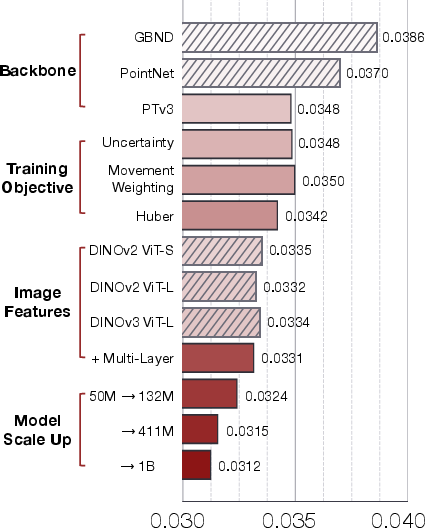

- They use a powerful 3D neural network backbone (a Point Transformer) that can handle lots of points and learn long-range effects (like how pulling one end of a cloth moves the other).

- They predict motion for all points in a “chunk” of time at once. This makes the predictions smoother and fast to compute (about 0.1 seconds per pass).

- Training data (how they taught it)

- Real robot videos: They built a pipeline to turn regular robot recordings into high-quality 3D data. They improved depth maps, fixed camera positions, and tracked points over time. That let them figure out how points actually moved in the real world.

- Simulation: They also used a realistic simulator with lots of home activities, where ground-truth 3D motion is known.

- Scale: About 2 million short interaction trajectories (around 500 hours). This is huge for 3D dynamics.

- Training tricks (to make learning stable and fair)

- Focus on moving points: Most dots don’t move at any moment, so they gently “upweight” the dots that do move. That gives the model clearer signals about real interactions.

- Handle noise: Real data is messy. The model also predicts how certain/uncertain it is about each dot’s motion and uses a robust loss, so it doesn’t overfit to bad labels.

- Use strong visual features: They attach pre-trained 2D image features to the 3D dots, which helps the model understand object boundaries and parts without needing manual labels.

- Using the model to act (planning)

- They plug PointWorld into an MPC planner (think: “try many short action guesses, keep the best ones, repeat”). For each guessed gripper path, the model predicts how the scene will move. The planner then picks actions that move selected dots (like the tip of a spoon or the handle of a drawer) toward goals.

What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the main takeaways, explained in short:

- A unified 3D language for seeing and acting works. Describing both the scene and the robot’s planned moves as dots in 3D lets one model learn across different robots and tasks.

- It runs in real time. Predictions take about a tenth of a second, fast enough to be used inside a live planner on a physical robot.

- It generalizes. A single pre-trained checkpoint controlled a real robot to:

- Push rigid objects

- Manipulate flexible items (like cloth)

- Move articulated things (like doors or drawers)

- Use tools

- All from just one RGB-D image, with no extra demos or fine-tuning at test time.

- Bigger and better makes a difference. Modern 3D backbones (Point Transformers), focusing losses on moving points, uncertainty handling, and using good 2D features all noticeably improve accuracy. Scaling up the model and the data produces steady, predictable gains.

- Smart action representation helps. Using gripper point flows (instead of whole-body or joint angles) is an efficient way to capture contact where it matters and to transfer learning between different robot bodies.

- Strong data pipeline = strong model. Carefully fixing depth, camera pose, and tracking in the real-world dataset substantially improved training quality and final performance.

These results matter because they move robots closer to “intuitive physics” in the real world—seeing, thinking, and predicting like humans do when they imagine an action and its effects.

What could this lead to?

- More general-purpose robots: A single model that understands 3D interaction could help robots handle many tasks in homes, hospitals, and warehouses without retraining for each new scene.

- Easier transfer between robots: Because actions are defined in 3D, the same model can support different robot shapes and grippers.

- Faster development: The authors plan to open-source code, data, and checkpoints. That means other teams can build on this and push the limits further.

- Better planning and safety: Predicting how objects will move before acting can reduce trial-and-error, avoid collisions, and make robots more reliable around people.

- A foundation for future skills: With accurate, fast 3D predictions, robots can be taught higher-level behaviors (like multi-step tasks) using the same world model as a “physics engine in the loop.”

In short, PointWorld shows a practical path to large, fast, and transferable 3D world models that help real robots understand and shape the world around them.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper.

- Embodiment generalization at deployment: The model is only validated on a single physical platform (Franka), leaving open whether the action-as-gripper-point-flows representation transfers zero-shot to unseen physical robots with different kinematics, compliance, and gripper geometries (e.g., suction, soft hands, multi-fingered hands, mobile bases).

- Forces, friction, and compliance: Dynamics are modeled purely as 3D displacements without explicit contact forces, friction, or compliance; it remains unclear how to incorporate and exploit force/torque or tactile sensing to improve predictions and control in contact-rich manipulation.

- Multi-modal futures: The model predicts a single mean trajectory with per-point aleatoric uncertainty but does not model branching outcomes (e.g., slip vs. stick, alternative cloth folds); exploring generative or ensemble approaches for multi-modal future prediction is an open direction.

- Longer-horizon dynamics and memory: The approach uses short, chunked horizons (, ≈1 s) and a static point set per forward pass; how to maintain and update a belief state over longer horizons with re-perception, occlusions, and persistent object states remains unexplored.

- Occlusions and unseen geometry: Training ignores occluded points (via tracker visibility) and inference relies on a single static point cloud; how to robustly infer and update hidden geometry (implicit shape completion) during closed-loop execution is not validated or quantified.

- Action representation coverage: Actions are represented as dense point flows on grippers (300–500 points) for efficiency; the paper leaves open how representation granularity, sampling density, and inclusion of velocities/accelerations affect performance and transfer, especially for whole-body and mobile manipulation.

- Control constraints and safety: The MPC cost uses point-goal tracking without explicit collision avoidance, joint limits, or reachability under uncertainty; integrating model-predicted uncertainty and safety constraints into risk-aware planning is an open challenge.

- Policy learning vs. planning: The work focuses on sampling-based MPC; whether the learned world model enables data-efficient policy learning (model-based RL) or offline policy synthesis, and how it compares in success, robustness, and compute, is left unexamined.

- Task specification and autonomy: Task-relevant points and goals are set via GUI or VLM, but the paper does not study automatic goal discovery, reward inference, or semantic grounding at scale for diverse tasks in-the-wild.

- Cross-domain transfer mechanisms: While real-sim co-training helps, the mechanism of transfer (feature sharing, dynamics biases) and optimal mixtures or curriculum to bridge sim-to-real are not established; systematic domain adaptation strategies are not explored.

- Data coverage and bias: The curated dataset lacks quantified coverage across materials (fluids, granulars), articulation types, deformability regimes, and motion speeds; evaluating and expanding coverage and diversity needed for broader generalization is an open need.

- Annotation fidelity and validation: Real-world point-flow labels are pseudo-ground-truth from stereo depth, extrinsics optimization, and 2D tracking; external validation with ground-truth motion capture or instrumented rigs (e.g., fiducial-labeled objects) is missing to quantify absolute accuracy and residual biases.

- Partial observability modeling: The approach does not explicitly maintain a probabilistic belief or uncertainty over unobserved state; investigating Bayesian or learned latent-state models that fuse intermittent observations with predictions could address information gaps.

- Material and articulation identification: Although DINOv3 features may offer objectness priors, the model has no explicit mechanism to infer or parameterize materials (e.g., stiffness, friction) or articulation (joints, constraints); learning explicit latent physical properties for generalization is open.

- Physical consistency metrics: Evaluation uses per-point error on moving points, but there is no assessment of physical consistency (contact timing, non-penetration, conservation constraints); developing and reporting physics-aware metrics would strengthen claims.

- Failure modes and robustness: Real-robot trials report success rates but do not categorize or analyze failure modes (e.g., depth errors, contact misprediction, planner drift); systematic robustness analysis under perturbations (lighting, texture, sensor noise, occlusions) is lacking.

- High-speed and impact dynamics: The model uses 0.1 s steps and is not evaluated on fast or impact-heavy interactions (hammering, cutting, throwing); extending to high-speed regimes and validating temporal resolution requirements remains open.

- Uncertainty utilization in control: Per-point log-variance is predicted but not used in MPC; incorporating uncertainty into sampling, costs, and safety (e.g., chance constraints, risk-aware MPPI) is not explored.

- Continuous online updating: The model runs zero-shot without adaptation; investigating online learning, self-supervised correction from robot rollouts, and mechanisms to prevent catastrophic drift is an open direction.

- Multi-view inference and sensor fusion: Although training uses multiple cameras, inference demonstrations emphasize single RGB-D capture; the benefits of multi-view fusion (and adding tactile/force sensors) on prediction and control are left unquantified.

- Computational efficiency and deployment: PTv3-1B yields ≈0.12 s forward passes, but training/inference energy, memory footprint, and edge deployment constraints are not analyzed; determining the optimal size-performance trade-off for real-time robotics is needed.

- Theoretical understanding: There is no theory on why 3D point flow unification should generalize across embodiments and tasks; studying identifiability, sample complexity, and generalization bounds in partially observable, contact-rich 3D dynamics is open.

- Generalization to non-prehensile and complex tool use: While some tool use is shown, systematic evaluation on diverse non-prehensile skills (e.g., sweeping, levering) and tools with complex geometry and compliance is missing.

- Mobile manipulation and whole-body in real hardware: Despite simulation coverage, real-world experiments are limited to a single-arm setup; validating the approach on mobile bases and bimanual systems in the real world is an open step.

- Planner–model co-design: The sampling strategy (time-correlated spline noise, horizon choice) is fixed; studying planner hyperparameters and co-design with the model (e.g., differentiable planning, gradient-based updates) may improve performance.

- Alternative training objectives: Weighted Huber regression stabilizes training, but the paper does not compare to contrastive, self-supervised, or physics-regularized objectives that could improve learning under noise and partial observability.

- Interpretability and causal analysis: The model implicitly encodes contact and objectness; tools to probe what is learned (e.g., friction coefficients, joint types) and manipulate these latents for counterfactual prediction or debugging are missing.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical applications that can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s open-source model, dataset, and annotation pipeline, as well as standard robotics tooling (URDF, RGB-D, MPC/MPPI).

Industry

- Real-time manipulation planning from a single RGB-D image

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics, retail robotics

- Workflow: calibrate cameras to the robot, load the robot’s URDF, specify task-relevant points (via GUI or VLM), run MPPI with the pre-trained 3D world model to plan end-effector trajectories for pushing, grasping, opening, cloth handling, and simple tool use

- Tools/products: ROS2 nodes for “PointWorld-MPPI,” “URDF-to-point-flow” converter, goal-point GUI, integration with Viser for rollout visualization

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to at least one calibrated RGB-D view; accurate URDF and proprioception; short-horizon planning suffices; GPU for 0.1 s inference; reasonable depth quality in the environment

- Rapid adaptation across robot embodiments without re-collecting demonstrations

- Sectors: robotics platforms, system integrators

- Workflow: use embodiment-agnostic 3D action representation (gripper point flows); swap robot assets via URDF; reuse the same pre-trained world model across arms and hands

- Tools/products: “Embodiment Bridge” library mapping URDF links to action point flows

- Assumptions/dependencies: URDF fidelity (geometry/kinematics), gripper geometry dominates contact, consistent camera calibration

- Pre-deployment “what-if” physics previews for collision and disturbance checks

- Sectors: automated assembly, packaging, test & validation

- Workflow: visualize predicted point flows to assess unintended motion of nearby items, evaluate contact stability and clearance, gate unsafe trajectories using uncertainty predictions

- Tools/products: rollout viewer (Viser + PointWorld), controller-side uncertainty gates

- Assumptions/dependencies: short horizon forecasts (≈1 s) are sufficient to flag high-risk contacts; robust cost functions; calibrated RGB-D

- Teleoperation assist with predictive overlays

- Sectors: remote manipulation (e.g., hazardous environments, field service)

- Workflow: overlay predicted scene motion in the operator’s view to anticipate object movement during gripper approach and contact; adjust teleoperation commands accordingly

- Tools/products: operator UI plugin to render 3D flow heatmaps and uncertainty

- Assumptions/dependencies: synchronized camera feeds; reliable depth; GPU at the edge or in the cloud

- Quality assurance for deformable/articulated object handling

- Sectors: e-commerce fulfillment, recycling, food processing

- Workflow: use predicted flows to verify policy compliance (e.g., drawer opening without over-stressing joints, cloth manipulation without excessive slip)

- Tools/products: compliance checker integrating predicted displacements with thresholds

- Assumptions/dependencies: coverage in training data for target object classes; high-quality depth for fine geometry

Academia

- A standardized benchmark and recipe for scaling 3D world models

- Use: ablation and scaling studies on backbones, objectives, partial observability; compare dynamics accuracy via dense per-point metrics on moving points

- Tools/products: open-source dataset (~2M trajectories), PTv3-based implementations, evaluation scripts

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to GPUs; adoption of shared evaluation protocol; consistent data preprocessing

- Data-efficient planning and model-based RL experiments

- Use: plug the pre-trained model into MPPI, CEM, or hybrid MBRL pipelines to study sample efficiency and generalization in in-the-wild settings

- Tools/products: “PointWorld-Planning Kit” integrating MPPI and cost functions defined over point flows

- Assumptions/dependencies: short-horizon predictions; task-point specification (human or VLM); environment partial observability

- Markerless 3D annotation pipeline for existing datasets

- Use: upgrade legacy robotics datasets with accurate depth, extrinsics, and 3D point tracks using FoundationStereo, VGGT refinement, and CoTracker3 lifting

- Tools/products: annotation scripts, quality metrics (depth reprojection loss, alignment F1)

- Assumptions/dependencies: multi-view RGB or stereo availability; acceptable image quality; computational resources for offline processing

Policy

- Evidence-driven safety gating using model uncertainty

- Use: incorporate aleatoric uncertainty predictions into safety filters for deployment approvals and incident reduction

- Tools/products: uncertainty-aware controllers; audit logs with predicted vs. realized flows

- Assumptions/dependencies: calibrated uncertainty heads; thresholds aligned with risk tolerance; human-in-the-loop review for high-risk tasks

- Standardization of open-world manipulation evaluation

- Use: adopt per-point, per-timestep metrics (moving-point L2) over short horizons as complementary, discriminative measures to task success rates

- Tools/products: shared benchmarks and reporting templates

- Assumptions/dependencies: community buy-in; accessible datasets and code; agreed-upon calibration protocols

Daily Life

- Hobbyist and lab-scale robot projects with real-time physics previews

- Use: low-cost RGB-D sensors and open-source URDFs to visualize likely object motion before executing a manipulation

- Tools/products: simplified “PointWorld Preview” app, ROS integration

- Assumptions/dependencies: basic camera calibration; limited horizon tasks; consumer GPUs or cloud inference

- Instructional tools for teaching geometry-of-contact

- Use: visualize 3D flows during everyday tasks (e.g., opening doors, organizing items) to build intuition for safe, efficient manipulation

- Tools/products: interactive lesson modules and visualizers

- Assumptions/dependencies: simplified UIs; curated examples; short-horizon predictions

Long-Term Applications

Below are applications that require further research, scaling, or validation (e.g., longer horizons, broader data coverage, safety certification, and robust multi-view sensing).

Industry

- General-purpose mobile manipulators in unstructured environments

- Sectors: household service robots, hospital logistics, last-meter delivery

- Workflow: extend short-horizon dynamics to hierarchical, long-horizon planning; combine with navigation and high-level goal reasoning

- Tools/products: “World-Model Stack” integrating PointWorld with task/planning layers and LLM-driven goal selection

- Assumptions/dependencies: longer-horizon dynamics modeling; reliable multi-camera setups; robust grasping and recovery strategies; safety certification

- Fleet-wide embodiment-agnostic training and deployment

- Sectors: robotics OEMs and operators with diverse hardware

- Workflow: train a unified model across many URDFs; centrally update and serve model snapshots; automatically adapt contact reasoning to new grippers

- Tools/products: “Embodiment Hub” (URDF registry, auto-calibration, and model serving)

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized asset metadata; scalable data curation; MLOps for embodied AI

- High-precision manipulation in regulated domains

- Sectors: medical robotics, electronics assembly, aerospace

- Workflow: leverage 3D world modeling for delicate, sub-centimeter tasks with deformable and articulated parts under strict QA

- Tools/products: compliance and validation suites; uncertainty-to-risk translation layers

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-specific data (materials, tolerances), higher-fidelity sensors, certifiable models, stringent safety cases

Academia

- Long-horizon, compositional 3D world models

- Use: memory-augmented, hierarchical models that chain short-horizon flows; integrate relational reasoning for multi-object interactions

- Tools/products: hybrid architectures (PTv3 + temporal modules); curriculum datasets; multi-embodiment training protocols

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalable compute; richer supervision (materials, articulation labels); new objectives for temporal consistency

- Closed-loop learning from real-world deployment

- Use: collect on-policy interaction data to refine the model; explore active learning and uncertainty-guided data acquisition

- Tools/products: “Deploy-and-Improve” pipelines; data selection policies driven by uncertainty and novelty

- Assumptions/dependencies: safe exploration strategies; automated labeling; ethics/compliance for data collection

Policy

- Regulatory frameworks for embodied foundation models

- Use: define standards for data provenance, calibration procedures, uncertainty reporting, and incident audits for robot deployments powered by world models

- Tools/products: certification checklists; safety case templates; compliance monitors

- Assumptions/dependencies: cross-industry coordination; testbeds for benchmarking; clear mappings from metrics to risk levels

- Privacy and data governance for in-the-wild robot sensing

- Use: guidance on handling RGB-D captures in homes/workplaces, anonymization, retention policies, and model updates

- Tools/products: privacy-preserving annotation pipelines; on-device inference

- Assumptions/dependencies: legal and ethical frameworks; hardware support for on-device compute

Daily Life

- Household robots capable of robust deformable object manipulation

- Use: laundry folding, tidying, and delicate item handling using world-model-based planning

- Tools/products: consumer-grade robots with multi-view RGB-D; integrated planning apps

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable sensing in cluttered homes; extended training for household object diversity; safety layers for human–robot interaction

- AR “physics preview” for task planning

- Use: smartphone or headset overlays that predict how items will move when pushed or grasped; assist users in safe, efficient manipulation

- Tools/products: AR apps powered by lightweight variants of the 3D world model

- Assumptions/dependencies: high-quality depth on consumer devices; fast on-device inference or low-latency edge compute

Cross-cutting Dependencies and Assumptions

- Sensor quality and calibration: accurate metric depth and camera extrinsics are pivotal; the paper’s annotation pipeline (FoundationStereo, VGGT refinement, CoTracker3 lifting) is a strong immediate tool but may need domain-specific tuning.

- Short-horizon modeling: the current strengths are over ≈1 s horizons; longer-horizon behavior requires hierarchical planning and memory modules.

- Compute: real-time inference (≈0.1 s) typically needs a modern GPU; embedded deployment or AR variants require further optimization.

- Goal specification: many tasks benefit from task-relevant point selection (human GUI or VLM); fully autonomous goal discovery is an active research area.

- Training coverage and generalization: success depends on diversity and fidelity of training data (objects, materials, articulations, embodiments, viewpoints).

- Safety and uncertainty: aleatoric uncertainty heads can gate risky actions, but calibration and policy thresholds must be validated against domain-specific safety requirements.

Glossary

- Aleatoric uncertainty regularization: A training technique that models inherent data noise by predicting variance and weighting residuals accordingly. "we adopt aleatoric uncertainty regularization~\cite{kendall2017uncertainties,novotny2017learning,vggt} by predicting a scalar log-variance "

- Backbone: The core neural network architecture used to process inputs and features. "we deliberately build on top of state-of-the-art point cloud backbones~\cite{ptv3}"

- BEHAVIOR-1K (B1K): A large-scale simulated dataset of robot interactions in realistic home environments. "we use BEHAVIOR-1K~\citep{behavior} (B1K)"

- Bimanual: Using two arms or hands for manipulation. "spanning single-arm, bimanual, and whole-body interactions"

- Camera extrinsics: Parameters defining a camera’s pose relative to a global (robot) frame. "hand-eye calibration (i.e., camera extrinsics in robot base frame)"

- CoTracker3: A 2D point-tracking method that provides dense correspondences and visibility. "per-pixel point tracking using CoTracker3~\citep{karaev2025cotracker3}"

- Depth reprojection loss: An error metric comparing analytical vs observed depth after projecting geometry into the camera. "We further compute depth reprojection loss (differences between analytical and observed depth of robot surface)"

- DINOv3: A pretrained vision transformer providing dense image features used to featurize points. "Scene points are featurized with frozen DINOv3~\citep{dinov3,rayst3r}"

- DROID: A diverse real-world robot manipulation dataset used for training and evaluation. "We leverage DROID~\cite{droid}, a robot manipulation dataset"

- Embodiment-agnostic: Independent of specific robot morphology or kinematics, enabling cross-robot learning. "an embodiment-agnostic description of robot actions"

- End-effector: The robot’s tool or gripper at the end of its arm that interacts with the environment. "plans a sequence of endâeffector pose targets in "

- Exponentiated weights: Weights computed by exponentiating (negative) costs during sampling-based optimization. "by computing exponentiated weights ( \omega_\ell \propto \exp(-J{(\ell)}/\beta) ) over samples"

- Forward kinematics: Computing the pose of robot links or attached points from joint angles and the URDF. "via forward kinematics (using the URDF and joint configuration)"

- FoundationStereo: A stereo-based depth estimation model used to obtain metric depth. "we replace sensor depth with stereo-estimated depth from FoundationStereo~\citep{foundationstereo}"

- Graph-based neural dynamics (GBND): Neural dynamics models that use graph structures and message passing. "Graph-based neural dynamics (GBND) models are widely used for dynamics modeling due to their relational inductive bias"

- Hand-eye calibration: Calibrating camera pose(s) with respect to a robot’s base frame. "hand-eye calibration (i.e., camera extrinsics in robot base frame)"

- Heterogeneous embodiments: Diverse robot bodies, grippers, and kinematic configurations. "to learn from heterogeneous embodiments (different kinematics, gripper geometries, and even different numbers of grippers)"

- Huber loss: A robust regression loss that blends L1 and L2 behavior. "and further using a Huber loss on the residual."

- In-the-wild: Unstructured, real-world environments outside curated labs. "from a single image captured in-the-wild."

- Joint-space commands: Low-level robot actions specified by joint configurations. "robot joint-space actions"

- Model Predictive Path Integral (MPPI): A sampling-based optimization method within MPC for planning. "sampling-based MPC (e.g., MPPI~\citep{mppi})"

- Model-predictive control (MPC): Planning by optimizing action sequences with a predictive model of dynamics. "model-predictive control (MPC) framework"

- Movement likelihood: A soft probability indicating whether a scene point is moving at a given timestep. "by a soft movement likelihood "

- Movement weighting: Loss reweighting to focus training on points that are moving. "The movement weighting, used in the training objective, effectively biases the training towards scene points that are moving"

- Multi-step (chunked) formulation: Predicting multiple future steps in a single forward pass to improve consistency and efficiency. "we adopt a multi-step (chunked) formulation for data-driven modeling"

- Partial observability: Only part of the true state is visible from sensor inputs. "operate on partially observable RGB-D image(s) in the wild"

- Photorealistic simulation: High-fidelity simulated environments that resemble real-world visuals. "Photorealistic simulation complements this with ground-truth supervision."

- Point cloud: A set of 3D points representing scene geometry. "a static full-scene point cloud"

- Point flows: Per-point 3D displacements over time representing dynamics. "predicts full-scene 3D point flows"

- Proprioception: Internal sensing of a robot’s joint states and other body parameters. "robot flows obtained from known robot geometry, kinematics, and proprioception"

- Radiance fields: Volumetric representations of scene appearance and geometry (e.g., in NeRF). "radiance fields or Gaussians"

- RGB-D: Color images with aligned depth measurements. "Given calibrated RGB-D"

- Robot description file (URDF): A machine-readable specification of a robot’s links, joints, and geometry. "a robot description file (URDF)"

- Sampling-based planner: A planner that samples candidate trajectories and evaluates them to update a nominal plan. "with a sampling-based planner MPPI~\citep{mppi} that plans"

- Scaling laws: Empirical relationships indicating performance improvements with increased data/model size. "scaling laws, and domain transfers under zero-shot and finetuned settings"

- SE(3): The group of 3D rigid-body transformations (rotations and translations). "in "

- Sim-to-real gaps: Discrepancies between results in simulation and behavior in the real world. "face sim-to-real gaps"

- Sparse convolutional nets: Convolutional neural networks operating on sparse 3D voxel grids. "sparse convolutional nets~\cite{spconv2022}"

- Teleoperated: Robot interactions controlled by a human operator. "teleoperated interactions"

- Temporal embedding: Feature vectors encoding time information for sequential inputs. "robot points with temporal embeddings"

- Time-correlated (cubic-spline) noise distribution: Structured noise with temporal correlation used to sample action perturbations. "using a time-correlated (cubic-spline) noise distribution"

- Trajectory cost: A scalar objective accumulated over a trajectory to evaluate candidate plans. "and a trajectory cost is accumulated."

- U-net hierarchy: A multiscale encoder–decoder architecture enabling long-range attention. "while U-net hierarchy enables attention over progressively coarser point sets"

- VGGT: A learned 3D reconstruction model that jointly estimates depth and camera pose. "Frontier 3D reconstruction models such as VGGT~\citep{vggt} jointly estimate depth and camera parameters"

- Vision-LLMs (VLMs): Models that jointly process images and text for grounding and reasoning. "or by VLMs~\cite{huang2024rekep}"

- Wrist-mounted camera: A camera attached to the robot’s wrist providing egocentric views. "a wrist-mounted camera."

- Zero-shot: Generalizing to new domains or tasks without additional training. "under zero-shot and finetuned settings."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.