In-N-On: Scaling Egocentric Manipulation with in-the-wild and on-task Data (2511.15704v1)

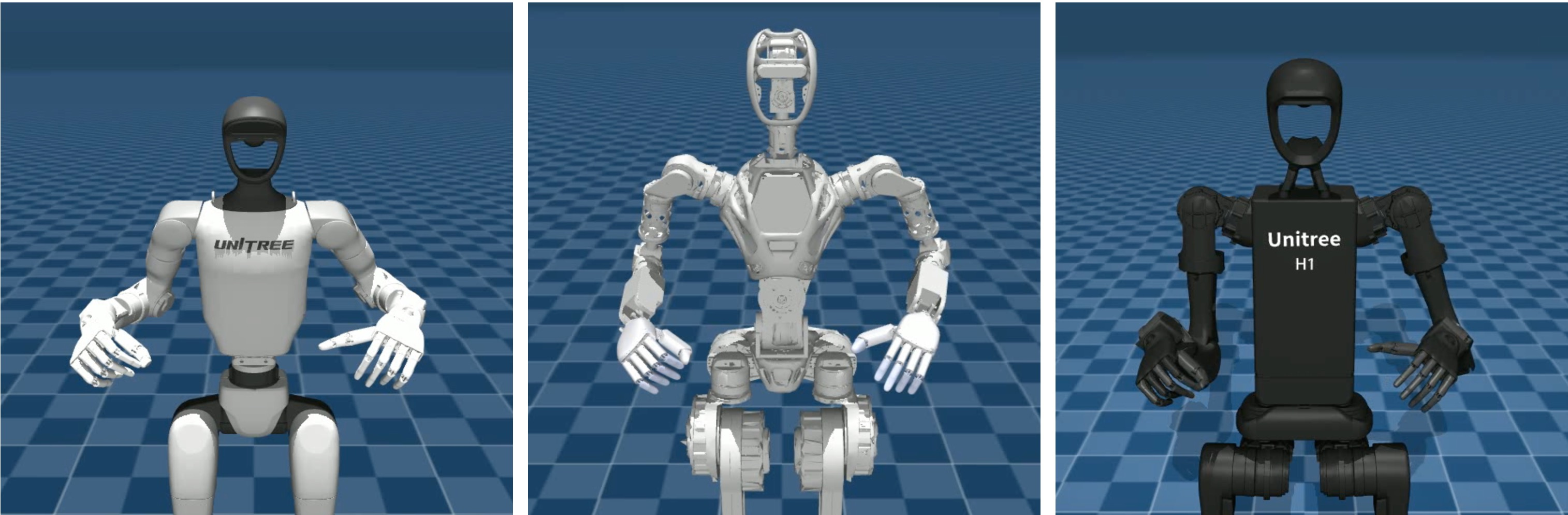

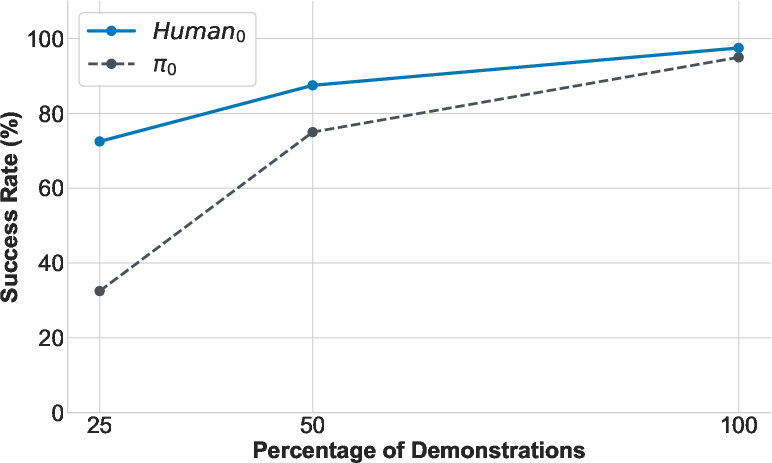

Abstract: Egocentric videos are a valuable and scalable data source to learn manipulation policies. However, due to significant data heterogeneity, most existing approaches utilize human data for simple pre-training, which does not unlock its full potential. This paper first provides a scalable recipe for collecting and using egocentric data by categorizing human data into two categories: in-the-wild and on-task alongside with systematic analysis on how to use the data. We first curate a dataset, PHSD, which contains over 1,000 hours of diverse in-the-wild egocentric data and over 20 hours of on-task data directly aligned to the target manipulation tasks. This enables learning a large egocentric language-conditioned flow matching policy, Human0. With domain adaptation techniques, Human0 minimizes the gap between humans and humanoids. Empirically, we show Human0 achieves several novel properties from scaling human data, including language following of instructions from only human data, few-shot learning, and improved robustness using on-task data. Project website: https://xiongyicai.github.io/In-N-On/

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching humanoid robots to use their hands better by learning from videos taken from a person’s point of view (like a GoPro on your head). The authors show a simple, scalable way to use two kinds of human videos to train robots:

- “In-the-wild” videos: everyday activities people do in many places.

- “On-task” videos: people doing the exact tasks we want the robot to do.

They build a big dataset called S and a robot control model called Human0, then test it on real humanoid robots to see if it can follow language instructions, learn from very few robot examples, and be more robust in real-world tasks.

Key Questions the Paper Tries to Answer

- How can we best use large amounts of human egocentric videos to train robot hand skills?

- What’s the right way to mix “in-the-wild” (broad, easy to collect) and “on-task” (specific, well-aligned) human data?

- Can learning from human videos help robots better understand language instructions, learn new tasks with very few robot demos, and handle messy, real-world situations?

- How do we prevent models from “cheating” by noticing if input comes from a human or a robot and overfitting to one setup?

How They Did It (Simple Explanation)

Data: Two Stages, Two Types

Think of training like building a sports player:

- Pre-training (practice): use lots of “in-the-wild” human videos (over 1,000 hours) plus some robot data to learn general skills and “common sense.”

- Post-training (coaching): use focused “on-task” human and robot videos (20+ hours) to polish skills for real jobs (like assembling a burger or pouring).

“In-the-wild” is broad and varied; “on-task” is small but exactly what we want robots to do.

A Common Representation for Humans and Robots

Humans and robots have different bodies. To teach a robot from human video, they convert both into the same simple description:

- Head position/orientation (where your “camera” is).

- Left and right wrist positions relative to the head.

- Fingertip positions (for all five fingers on each hand).

- Optional: a single “gripper opening” value mapped from the distance between thumb and index finger.

This is like writing down just the essential “where are the hands and fingers” info, so videos from different people and different robots can be used together. They provide software to translate robot joint angles to this human-like description and back (using IK/FK, which you can think of as “figure out how to move the robot joints so the hands go where you want”).

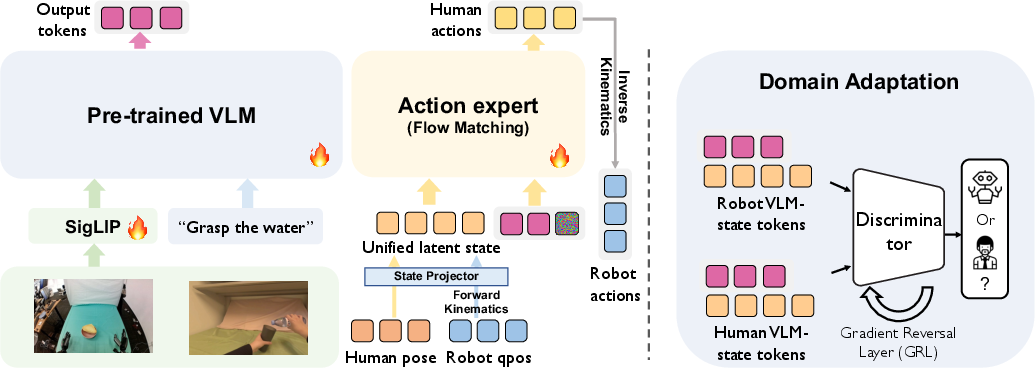

The Model: Human0

Human0 is a vision-language-action model. In everyday terms:

- It looks at the scene (images from the robot’s cameras).

- It reads the instruction (like “pick up the red cup”).

- It predicts the next hand and finger movements to do the task.

To train action prediction, they use “flow matching.” Imagine starting from a noisy guess for the action and gently nudging it toward the correct action step by step—like sketching a path from a rough idea to the right move.

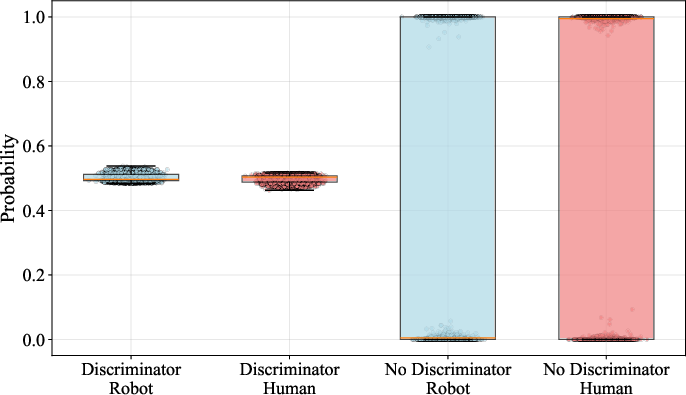

Preventing “Cheating” with Domain Adaptation

They found the model could secretly tell whether inputs came from a human or a robot and then overfit to one. To stop this:

- They add a small “discriminator” that tries to guess “human vs. robot” from the model’s internal features.

- They use a trick called a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) to make the main model learn features that confuse this discriminator. In plain terms: the model learns to ignore whether data comes from a human or a robot, focusing on the task instead.

This helps skills learned from people transfer to robots more reliably.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

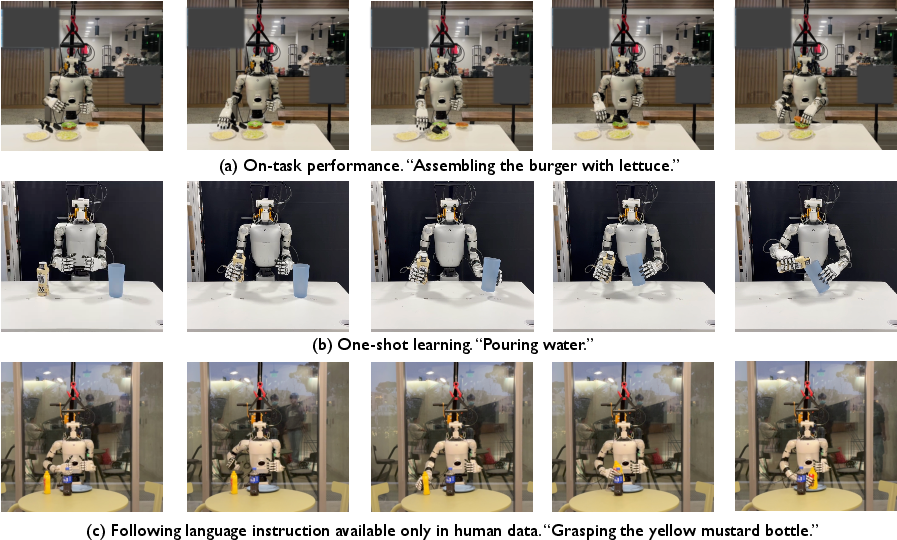

- Stronger language following: Human0 followed instructions about objects and tools that never appeared in robot training data but did appear in human videos. Example: in multi-object grasping, it correctly picked the requested item even among distractors.

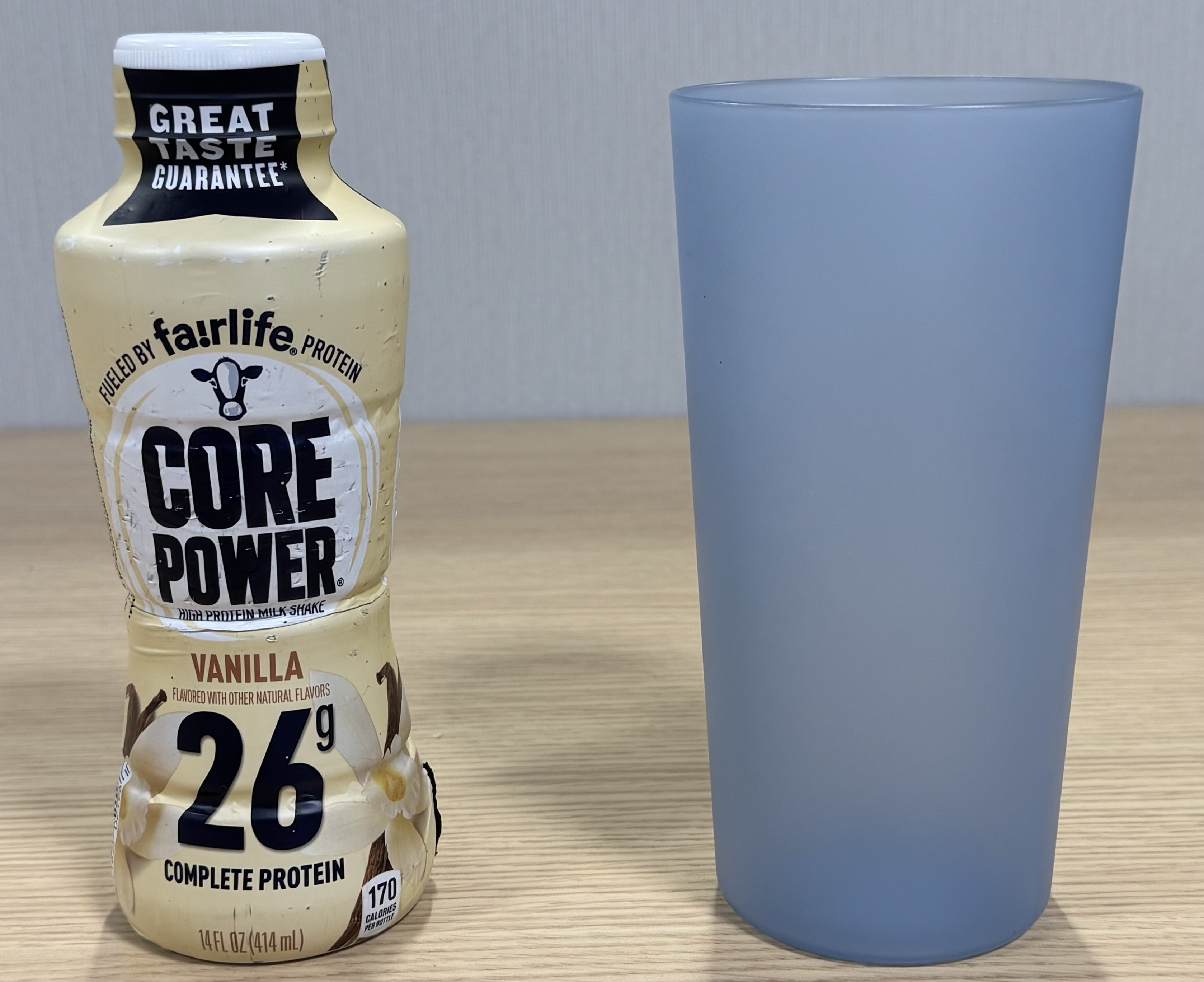

- Few-shot learning: With just one robot demonstration of a new task (like bimanual pouring), Human0 could start doing it, achieving meaningful success. This is a big step toward fast, low-cost robot training.

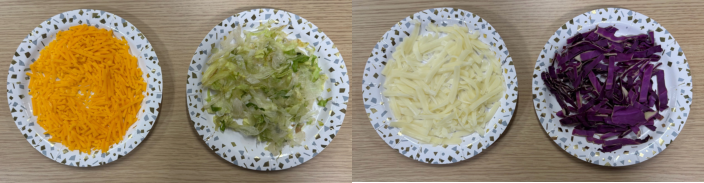

- More robustness in complex, real tasks: In a “fast food worker” scenario (assembling a burger using tongs, handling different ingredients), Human0 handled long sequences and messy setups better than other models.

- Domain adaptation helps: Making features “embodiment-agnostic” improved performance, especially when robot training examples were very limited.

- Outperforms baselines: On several tasks (single/multi-object grasping, burger assembly, pouring), Human0 beat other strong models trained mainly on robot data.

Implications and Impact

- Scalable training from everyday human videos: Since “in-the-wild” data is easy to collect, we can grow robot skills much faster and cheaper.

- Practical industry use: “On-task” human data (e.g., workers wearing smart glasses) can quickly tune robots for real jobs like food prep, packaging, or warehouse tasks.

- Better language-grounded manipulation: Learning from human videos enhances the robot’s ability to understand and follow spoken or written instructions.

- Cross-embodiment generalization: The human-centric representation and domain adaptation help knowledge from people transfer to different robots.

- Open resources: The authors plan to release the dataset (S), tools, and model weights, which can speed up progress for the whole community.

Bottom Line

Using both “in-the-wild” and “on-task” human egocentric videos—and training in two stages—helps robots learn hand skills that follow language, adapt quickly with few robot examples, and handle real-world complexity. This approach could make teaching robots much more like teaching humans: watch, practice, and then refine for the job.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, action-oriented list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that future work could address.

- Data mixing and scaling laws are not characterized: systematically vary human:robot sampling ratios and dataset sizes across tasks to quantify catastrophic forgetting, retention, and performance trade-offs; derive principled weighting/scheduling policies beyond manual sampler tweaks.

- Generalization to non-humanoid embodiments is untested: validate the unified human-centric state-action space and retargeting pipeline on diverse platforms (mobile manipulators, single-arm systems, parallel grippers, low-DoF hands) and quantify mapping fidelity and downstream control performance.

- Assumptions in the human-centric representation are unvalidated: test whether modeling wrists relative to head and “neglecting” anthropometric differences (e.g., height, limb lengths) impacts policy accuracy; evaluate normalization or personalized calibration strategies.

- Fingertip-only hand modeling may be insufficient: compare fingertip keypoints against richer hand representations (joint angles, palm pose, contact states) and tactile/force proxies for precision, in-hand manipulation, and tool-use tasks.

- Language annotation provenance and alignment are unclear: document how language labels are obtained for in-the-wild datasets (e.g., EgoDex, ActionNet), their temporal alignment quality, and measure instruction grounding accuracy; create a standardized instruction–trajectory alignment protocol.

- Domain adaptation scope is limited to binary human vs robot: evaluate multi-domain adversaries (different human devices, environments, and robot embodiments), alternative objectives (MMD, contrastive/domain confusion, style augmentation), discriminator layer placement, and ablate the loss weight λ.

- Retention after post-training is not measured: explicitly evaluate pre-training skill retention and catastrophic forgetting on held-out pre-training tasks; compare mitigation methods (e.g., LwF, EWC, rehearsal buffers) beyond sampling strategies and GRL.

- Long-horizon temporal modeling is underexplored: introduce memory (e.g., recurrent/Transformer with temporal context), hierarchical policies, or subgoal discovery; benchmark on extended tasks with multi-step dependencies and delayed rewards.

- Statistical rigor is limited: increase trial counts, report confidence intervals and statistical significance, analyze inter-seed variability, and provide standardized evaluation protocols for each task and OOD condition.

- OOD robustness is weakly probed: stress-test with severe distribution shifts (lighting extremes, occlusions, motion blur, clutter density, moving agents, outdoor scenes) and quantify failure modes and recovery.

- Sensor modality effects are not studied: compare RGB-only 240×320 against higher resolution, depth/stereo, IMU, audio, and event cameras; quantify gains and compute trade-offs.

- Real-time systems constraints are unspecified: report inference latency, control loop frequency, compute requirements on robot hardware, and stability under delays; analyze the impact on contact-rich manipulation.

- Egocentric sensor calibration is not detailed: formalize head-camera to robot-base extrinsic calibration procedures; measure calibration error and its effect on control; evaluate device-specific discrepancies (Apple Vision Pro vs Meta Aria).

- Tool-use generalization is narrow: extend beyond tongs to knives, spatulas, ladles, scoops, clamps; build and evaluate tool-specific grasp/pose priors and retargeting strategies.

- IK/FK retargeting fidelity is not quantified: provide error distributions for pose retargeting across robots, analyze failure cases (closed-chain constraints, contacts, reachability), and evaluate differentiability/gradient quality in training.

- Integration with LLM-based planning is absent: paper compositional and multi-step instruction following, paraphrase robustness, and language-conditioned planning via LLMs/VLMs; measure gains over SigLIP-only grounding.

- Privacy, consent, and licensing are not addressed: release detailed data documentation (de-identification, subject consent, usage licenses, workplace data policies) and propose privacy-preserving pipelines for egocentric collection at scale.

- Safety considerations are minimal: define safety monitors, fail-safes, and intervention policies; quantify risk metrics for contact-rich and kitchen/food tasks; evaluate recovery under dangerous states.

- Quantitative scaling curves are missing: characterize performance saturation and diminishing returns when increasing in-the-wild hours vs on-task hours; identify optimal allocation for a fixed data budget.

- Few-shot and zero-shot boundaries are not mapped: rigorously determine which behaviors can be induced from human data alone, the minimal robot demonstration count per behavior, and task properties that drive few-shot success.

- Baseline coverage is limited: compare under matched training budgets to concurrent human-pretrained VLAs (e.g., Being-H0, EgoVLA, EMMA) and classical modular pipelines; ensure fairness in data, architectures, and tuning.

- Embodiment invariance granularity is coarse: move beyond binary human/robot to fine-grained invariance across multiple robot morphologies, hand DOFs, and kinematic structures; evaluate invariance diagnostics beyond linear probing.

- Annotation noise handling is not analyzed: quantify noise in wrist/fingertip trajectories from wearable devices, assess filtering/denoising pipelines, and measure downstream policy sensitivity to annotation quality.

- Low-level control and compliance are under-described: report controller settings (impedance/compliance), incorporate force/tactile feedback, and evaluate how control gains influence success in contact and pouring tasks.

- Closed-loop error recovery is not studied: analyze whether policies can detect and correct mid-trajectory errors, design recovery behaviors, and evaluate robustness to disturbances and partial execution failures.

- Multi-domain post-training effects are unknown: test whether post-training on one on-task domain harms performance on others; develop multi-domain post-training curricula that preserve cross-task generalization.

Glossary

- Affordance: In robotics and vision, the actionable possibilities of objects or environments; learning affordances helps derive manipulation strategies. "Modular methods learn affordance~\citep{wang2017-binge,mendonca2023-human-world,bahl2023affordances}"

- Attention head: A component of transformer architectures that performs attention computations over token sequences. "pass them though a attention head"

- Bimanual: Involving two hands; in robotics, policies or embodiments that use two manipulators simultaneously. "applicable to many egocentric bimanual embodiments"

- Catastrophic forgetting: The tendency of neural networks to forget previously learned information when trained on new tasks. "catastrophic forgetting~\cite{french1999-catastrophic,hancock2025-vlavlm}"

- Cross-embodiment learning: Learning across data from different robot morphologies or platforms to build general policies. "cross-embodiment learning from different robots~\citep{o2024-open-x,kim2024openvla,black2024pi_0}"

- Degrees of Freedom (DoF): The number of independent parameters that define a system’s configuration; in robots, joint or pose dimensionality. "kinematics, DoFs, and mechanical configurations can differ."

- Dexterous: Skilled, fine-grained manipulation, often requiring many degrees of freedom and precise control. "dexterous and long-horizon tasks~\citep{barreiros2025-lbm}"

- Domain adaptation: Techniques to make models generalize across differing data distributions or embodiments. "Human adopts domain adaptation technique to improve hidden states to fully utilize human training data."

- Domain-adversarial discriminator: A classifier trained adversarially to make learned features invariant across domains (e.g., human vs. robot). "We employ a domain-adversarial discriminator that takes SigLIP visual features and action-state embeddings as input"

- Egocentric: First-person perspective data capturing what the agent (human or robot) sees and does. "Egocentric videos are a valuable and scalable data source to learn manipulation policies."

- Embodiment-invariant representations: Feature encodings that do not reveal whether data comes from human or robot, enabling transfer. "embodiment-invariant representations, enabling effective transfer between human and robot observations."

- Flow matching: A generative modeling approach that learns a vector field mapping noisy samples toward targets; here used for action prediction. "a large egocentric language-conditioned flow matching policy, Human."

- Forward Kinematics (FK): Computing end-effector poses from joint angles using a robot’s kinematic chain. "IK/FK (Inverse Kinematics and Forward Kinematics)"

- Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL): A layer that multiplies gradients by a negative constant to enable adversarial domain adaptation. "Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL)~\citep{ganin2016-GRL}"

- In-Distribution (I.D.): Data that matches the distribution seen during training. "The I.D. setting tests the learned skills with language, scenes, and objects that approximately resemble corresponding sequences in the robot training demonstrations."

- In-the-wild data: Uncurated, naturally occurring data captured in diverse real-world environments and activities. "diverse in-the-wild egocentric data"

- Inverse Kinematics (IK): Computing joint configurations that achieve desired end-effector poses. "IK/FK (Inverse Kinematics and Forward Kinematics)"

- Latent space: A learned feature space where data is embedded for modeling and decoding. "operate in the unified latent space~\cite{wang2024-hpt}"

- Linear probing: Training a simple classifier on frozen representations to test what information is encoded. "we perform a simple linear probing study."

- Loco-manipulation: Coordinated locomotion and manipulation, often requiring whole-body control. "whole-body loco-manipulation"

- MuJoCo: A physics engine and simulator widely used for robotics research. "MuJoCo~\cite{todorov2012-mujoco}"

- Out-Of-Distribution (O.O.D.): Data that differs from the training distribution, used to test generalization. "The O.O.D. setting tests configurations that are unseen in the robot training data"

- Pinocchio: A rigid-body dynamics and kinematics library used for robotics modeling and optimization. "based on Pinocchio~\cite{carpentier2019-pinocchio}"

- Proprioceptive tokens: Encoded signals representing the agent’s internal state (e.g., joint positions) used as model inputs. "taking intermediate visual tokens and proprioceptive tokens as inputs."

- Retargeting: Mapping motions or poses from one embodiment to another (e.g., human to humanoid). "retargeting software suite supports retargeting different humanoids from/to the human-centric representation."

- SE(3): The Special Euclidean group in 3D representing rigid-body rotations and translations. "$\mathbf{T_{head} \in \mathbf{SE}(3)$"

- SigLIP: A vision-LLM that aligns image and text embeddings using a sigmoid loss, used here for visual tokenization. "Specifically, a SigLIP-based vision module extracts visual tokens"

- Unified human-centric state-action space: A common representation of states and actions anchored to human poses for cross-embodiment learning. "a unified human-centric state-action space"

- Vision-LLM (VLM): Models that jointly process visual inputs and text to enable tasks like grounding and captioning. "vision-LLMs (VLMs)"

- Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model: Models that integrate vision and language with action outputs for embodied control. "vision-language-action (VLA) models"

- Visuomotor: Relating visual perception to motor control; used to describe policies or priors that map vision to action. "refine the policy's language grounding and visuomotor control"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the paper’s dataset (S), base model (Human_0), unified human-centric state–action interface, domain adaptation recipe, and retargeting suite. Each bullet lists sector(s), suggested tools/workflows, and key dependencies/assumptions.

- Fast-food assembly and QSR automation (food service)

- Use case: Post-train Human_0 on on-task egocentric demos captured by workers (e.g., burger assembly with tongs, ingredient selection via language instructions) to build robust, long-horizon manipulation policies that generalize to new ingredients and layouts.

- Tools/workflow: Apple Vision Pro or Meta Aria for data capture; on-task post-training (70% human, 30% robot sampling as per paper); retargeting suite to the deployed humanoid; Human_0 weights; GRL-enabled domain adaptation; standard evaluation protocol (I.D./O.O.D).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to bimanual robots (e.g., Unitree G1/H1) with dexterous hands or tool use (tongs); workplace safety protocols; consented data collection; stable vision capture; compute for fine-tuning (single H100 feasible).

- Warehouse kitting and retail picking with open-vocabulary instructions (logistics, retail, manufacturing)

- Use case: Multi-object grasping where the robot picks SKUs specified by natural language (including items unseen in robot data), with few-shot adaptation to new SKUs and shelf layouts.

- Tools/workflow: In-the-wild pre-training + on-task post-training on shift-collected data; Human_0 fine-tune; unified human-centric mapping; QA with linear probing to check embodiment leakage; continuous data refresh loop.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Consented egocentric capture in facilities; product-level variability management; adequate lighting; accurate calibration of cameras to robot frames.

- Technician-guided line changeover and small-batch assembly (electronics, contract manufacturing)

- Use case: Record a technician’s on-task procedures (fasteners, feeders, simple tool use) and post-train a policy for rapid reconfiguration without large robot datasets.

- Tools/workflow: Meta Aria/AVP capture; retargeting to the plant’s robot; GRL domain adaptation; stepwise evaluation (stage success tracking as in staged pouring).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Tool availability and fixturing; reliable wrist/finger capture for fine manipulation; safety interlocks.

- Developer SDK for cross-embodiment integration (robotics OEMs, integrators)

- Use case: Integrate new robots into a human-centric action API using the open-source IK/FK retargeting suite (Pinocchio-based) to enable Human_0 fine-tuning on your platform.

- Tools/workflow: Retargeting suite + calibration scripts; unit tests using MuJoCo assets; sample pipelines for mapping joint states to the unified representation; model adaptor heads for state/action encoders.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Accurate robot kinematics and joint sensing; latency budget for real-time inference; adherence to state-space spec (head, wrists, fingertips/gripper distances).

- Academic teaching and benchmarking (education, academia)

- Use case: Course labs on egocentric manipulation, cross-embodiment learning, and domain adaptation; reproduce few-shot pouring and language-following experiments.

- Tools/workflow: S dataset (1,000+ hr pre-train + 20+ hr on-task), Human_0 weights, SigLIP vision backbone, GRL discriminator; train on single GPU for post-training.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Dataset licensing/availability as promised; optional hardware via simulation with provided MuJoCo assets; modest compute.

- Internal compliance kits for egocentric data capture (enterprise policy/compliance)

- Use case: Establish standard operating procedures and templates for consent, on-device redaction, retention, and purpose limitation for workplace egocentric capture.

- Tools/workflow: Data collection playbooks tailored to AVP/Aria; privacy checklists; sampling ratios; task segmentation guidance for on-task vs in-the-wild data.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Legal review; union/worker council engagement; secure storage and encryption; clear governance of AI training uses.

- Quality assurance for embodiment invariance (software, MLOps)

- Use case: Institutionalize the paper’s “linear probing” diagnostic to detect human/robot domain leakage and enforce GRL-based domain adaptation during training.

- Tools/workflow: Feature probes on intermediate tokens; GRL modules; A/B metrics dashboards; early-stopping and regularization monitors.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to model internals; reproducible training; robust feature logging.

- Tool-use to compensate for gripper limitations (robotics, hardware integration)

- Use case: Deploy policies that leverage simple tools (e.g., tongs) to handle food or deformable items, reducing reliance on expensive dexterous hands.

- Tools/workflow: Map gripper distance to thumb–index distance as per unified spec; on-task post-training with tool use; safety constraints on tool contact.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Tool standardization; safe grasp affordances; operator oversight during ramp-up.

- Few-shot onboarding for household tasks (consumer robotics)

- Use case: Teach personal robots to pour drinks, pick-and-place, load bowls with 1–5 demonstrations using egocentric capture; benefit from Human_0’s few-shot learning.

- Tools/workflow: HMD capture; quick post-train on consumer robot with a mapping layer; voice instruction grounding.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Availability of consumer-grade bimanual platforms; strong privacy defaults; supervised deployment in early stages.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, standardization, or hardware maturation before broad deployment.

- Generalist home and enterprise humanoids trained mostly from egocentric human data (consumer, facilities management)

- Use case: Zero-shot execution of novel routines from open-vocabulary instructions; robust long-horizon chores and facility tasks.

- What’s needed: Orders-of-magnitude more on-task data, richer tactile sensing, stronger safety guarantees, and continual learning with drift control.

- Human-centric action API standard across robot OEMs (robotics industry)

- Use case: Plug-and-play manipulation policies interoperable across embodiments via a shared state–action spec (head, wrists, fingertips/grippers).

- What’s needed: Standards consortium, shared benchmarks, compliance tests, and wide buy-in from OEMs.

- Workplace data cooperatives and benefit-sharing for egocentric data (policy, labor)

- Use case: Programs where workers opt-in to share on-task egocentric data for robot training with compensation and strict usage controls.

- What’s needed: Legal frameworks, privacy-preserving pipelines (e.g., on-device PII removal), auditability, and data trusts.

- Regulatory frameworks for egocentric capture and robot co-work safety (policy, regulators)

- Use case: Clear rules for collection, retention, and use of first-person data in industrial settings; risk management for humanoids near workers.

- What’s needed: Standards for anonymization, model auditing (feature-level invariance tests), incident reporting, and certification pathways.

- Auto-curation and on-device annotation loops (software, edge AI)

- Use case: AR glasses perform live segmentation, 2D/3D keypoints, and language annotation to create high-quality on-task datasets with minimal human labeling.

- What’s needed: Efficient on-device models, battery-friendly pipelines, robust task segmentation, and privacy-preserving analytics.

- Massive sim-to-real egocentric pre-training (robotics R&D)

- Use case: Generate large-scale synthetic egocentric manipulation data, retarget via the unified interface, and adapt with domain adversarial objectives.

- What’s needed: High-fidelity contact simulation, diverse assets, sim-to-real calibration, and automated discrepancy minimization.

- Skill marketplace for on-task egocentric packs (platform economy)

- Use case: Third parties publish task-specific data bundles; organizations download and post-train Human_0-derivatives for their environment.

- What’s needed: Licensing/IP frameworks, standardized metadata, quality ratings, safety attestations.

- Assistive healthcare procedures from clinician egocentric demos (healthcare)

- Use case: Robots learn safe, contact-rich assistance for activities of daily living and therapeutic routines from occupational therapists’ on-task data.

- What’s needed: Clinical trials, regulatory approvals, tactile/force sensing, rigorous fail-safe controls.

- Open-vocabulary collaborative HRI in dynamic scenes (public safety, disaster response, labs)

- Use case: Robots follow spoken or written instructions unseen in robot data for multi-object tasks, adapting on the fly with human partners.

- What’s needed: Robust open-vocabulary perception, low-latency grounding, calibrated uncertainty and task handoff.

- Safety-certified domain adaptation toolchains (certification, industrial safety)

- Use case: Auditable GRL/domain-invariance pipelines and probes that are recognized by standards bodies for mixed human/robot data training.

- What’s needed: Formal verification, standard test suites, traceable training provenance, and reproducibility requirements.

Notes on Assumptions and Dependencies

Across applications, feasibility hinges on:

- Data capture and governance: Access to Apple Vision Pro/Meta Aria or equivalent; informed consent; privacy-preserving processing; clear retention/use policies.

- Hardware maturity: Bimanual platforms with reliable IK, joint sensing, and dexterous or tool-mediated manipulation; safe human–robot interaction.

- Software/tooling: Availability of S dataset and Human_0 weights; the Pinocchio-based retargeting suite; SigLIP-based perception; GRL domain adaptation; sampling ratios (e.g., 70% human for post-training).

- Compute and MLOps: Single H100-level GPU suffices for post-training; scalable pipelines for larger pre-training; diagnostics (linear probing) to detect embodiment leakage.

- Task variability: Robustness to lighting, background, and novel objects; alignment between on-task human data distribution and target deployment.

- Legal and standards alignment: Workplace surveillance rules, labor agreements, and emerging certification norms for data and robot safety.

If these dependencies are met, the paper’s recipe—pre-train on in-the-wild egocentric data, post-train on on-task data, and enforce embodiment-invariant features—offers an immediate path to faster, cheaper, and more generalizable manipulation policies, with a clear roadmap to broader, standardized deployment.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.