Dream2Flow: Bridging Video Generation and Open-World Manipulation with 3D Object Flow (2512.24766v1)

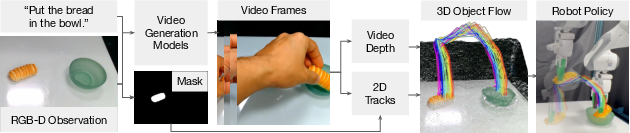

Abstract: Generative video modeling has emerged as a compelling tool to zero-shot reason about plausible physical interactions for open-world manipulation. Yet, it remains a challenge to translate such human-led motions into the low-level actions demanded by robotic systems. We observe that given an initial image and task instruction, these models excel at synthesizing sensible object motions. Thus, we introduce Dream2Flow, a framework that bridges video generation and robotic control through 3D object flow as an intermediate representation. Our method reconstructs 3D object motions from generated videos and formulates manipulation as object trajectory tracking. By separating the state changes from the actuators that realize those changes, Dream2Flow overcomes the embodiment gap and enables zero-shot guidance from pre-trained video models to manipulate objects of diverse categories-including rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular. Through trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning, Dream2Flow converts reconstructed 3D object flow into executable low-level commands without task-specific demonstrations. Simulation and real-world experiments highlight 3D object flow as a general and scalable interface for adapting video generation models to open-world robotic manipulation. Videos and visualizations are available at https://dream2flow.github.io/.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces Dream2Flow, a system that helps robots learn how to move objects in the real world by “watching” AI-generated videos. Instead of trying to copy a human’s hand motions directly, Dream2Flow focuses on the motion of the objects in the video and uses that object motion to guide the robot. This makes it easier for robots to perform many different tasks in new environments without special training for each task.

Key Objectives

The paper asks:

- How can we turn AI-generated videos into useful instructions for robots?

- Can we ignore the human’s exact movements and just follow how the object should move?

- Does this approach work across different kinds of objects (hard, bendy, with hinges, scattered materials)?

- How well does it work compared to other video-based methods?

- What parts of the system (like the video model or the robot’s motion model) matter most?

Methods and Approach

How it works (step-by-step)

Dream2Flow has three main steps:

- Generate a video: An AI video model is given a picture of the scene and a short text instruction (like “open the oven”) and creates a short clip showing the task being done.

- Extract object motion in 3D: The system finds the important object in the video (like the oven door), tracks points on that object across frames, and estimates how those points move in 3D (forward/backward, left/right, up/down). This motion is called “3D object flow.”

- Plan robot actions: The robot plans movements that make the real object in front of it follow the same 3D motion seen in the video. It can use either optimization (mathematical planning) or reinforcement learning (trial and error in simulation) to turn object motion into safe, precise robot commands.

What is “3D object flow”?

Think of placing tiny stickers all over an object. In the video, each sticker moves a little every frame. 3D object flow is a map of how all those stickers move through space. It doesn’t care who is moving the object (a human or a robot)—it only captures what the object itself should do. That’s powerful because robots and humans have very different bodies, but the desired object movement is the same.

Planning and control (in simple terms)

- Trajectory tracking: The robot tries to make the object follow the same “path” as in the video.

- Optimization: The robot picks a sequence of small moves that best match the object’s target motion.

- Reinforcement learning: In simulation, the robot learns a policy (a smart strategy) that gets rewards when the object’s motion matches the video’s 3D object flow.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

It works across many tasks and object types

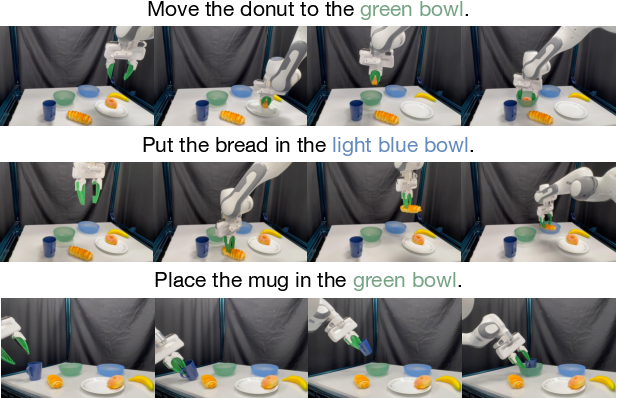

Dream2Flow was tested on:

- Push-T (pushing a T-shaped block to a target)

- Put Bread in Bowl

- Open Oven

- Cover Bowl (using a scarf)

- Open Door (with different robot bodies)

It handled rigid objects (blocks), articulated objects (doors, oven), deformable objects (scarf), and even granular materials (like pasta) by focusing on object motion, not human hand details.

Better than common alternatives

Compared to methods that track rigid transforms or dense optical flow from videos, Dream2Flow did better overall. That’s because many real objects bend, hinge, or change shape—so assuming the object moves rigidly often breaks. Dream2Flow’s per-point 3D motion is more flexible and robust.

A good reward for learning

Using 3D object flow as the “goal” in reinforcement learning led to policies that performed as well as those trained with handcrafted object state rewards. Different robots (a table-top arm, a quadruped, a humanoid arm) learned different strategies to achieve the same object motion—showing that Dream2Flow’s object-focused target works across different robot bodies.

The choice of video model matters

Some video generators produced more reliable object motions than others. Models that kept the camera still and predicted physically correct movements (like the correct hinge direction on an oven) led to better robot performance.

The robot’s dynamics model matters

When planning pushes, a “particle-based” model (predicting motion for many points on the object) worked much better than simpler models that only predict the object’s overall pose. Predicting per-point motion helps the robot plan rotations and contact-aware movements more accurately.

Current limitations and failure cases

- Video artifacts: Sometimes the video morphs the object or adds fake objects, which confuses tracking and planning.

- Tracking issues: If the object goes out of view or rotates a lot, point tracking can fail.

- Grasp selection: If the robot grasps the wrong part, the motion doesn’t match the intended flow.

Implications and Impact

Dream2Flow shows a promising way to connect “what we want to happen” (object motion) with “how the robot should move” (its actions), without relying on expensive robot-specific training data. By using off-the-shelf video and vision tools, it:

- Makes it easier to give robots instructions in plain language (paired with a scene image).

- Scales across many object types and tasks because it doesn’t depend on rigid-body assumptions.

- Bridges the gap between human demonstrations (in videos) and robot actions by focusing on the shared goal: the object’s motion.

If these tools keep improving—especially video generation quality and robust 3D tracking—robots could learn new tasks directly from visual imagination, making them more adaptable in homes, factories, and unstructured environments.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains uncertain or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide actionable future research.

- Embodied video generation: The pipeline avoids showing the robot in prompts due to implausible contacts, leaving open how to condition video models on specific robot morphology, kinematics, and reachability to produce physically feasible, robot-aware rollouts.

- Camera motion and egomotion: Dream2Flow assumes a static camera; generated clips with camera motion break the interface. How to estimate and remove egomotion (e.g., per-frame pose SLAM) to recover object flow robustly?

- Monocular depth scale drift: Depth is globally aligned only via a single-frame scale/bias. There is no per-frame correction for scale/shift drift or temporal inconsistency. How to enforce temporally consistent metric depth across the entire video?

- Detecting/repairing bad generations: Object morphing, hallucinations, and articulation errors are a major failure mode. There is no mechanism to detect, reject, or repair such videos before planning. Can physics- or geometry-based plausibility checks and regeneration loops be integrated?

- Single-object focus: The method extracts flow for a single “relevant” object. Multi-object interactions (e.g., tool use, coupled objects) and flow assignment across instances remain unsupported.

- Robust segmentation and object selection: The approach relies on GroundingDINO+SAM2 and a single bounding box; robustness to incorrect or partial masks, heavy occlusion, and appearance changes is not characterized. Can active refinement, multi-frame segmentation, or interactive disambiguation improve reliability?

- Occlusion reasoning: When points are occluded, costs are down-weighted, but there is no predictive handling of visibility or shape completion. How to model occlusion transitions and reconstruct occluded geometry for stable tracking?

- Temporal alignment: Time alignment between video and execution uses uniform warping or nearest-shape matching. A principled, robust time-warping (e.g., DTW with constraints) and online re-timing strategy is missing.

- Physical structure priors: 3D object flow is kinematics-only; it ignores rigidity, articulation axes, joint limits, friction, and non-penetration. How to inject structure priors (rigid parts, joints) and contact constraints into flow extraction and planning?

- Articulation inference: The system does not infer articulation models (e.g., hinge axis) and is vulnerable when video models imply incorrect axes. Can articulation discovery be coupled with flow to constrain feasible object motions?

- Grasp selection and part targeting: Grasping is chosen by proximity to the generated video’s human thumb (HaMer) plus AnyGrasp proposals. This heuristic may not generalize across tasks, objects, or embodiments. How to infer task-relevant grasp sites/affordances directly from the flow or language?

- Deformable and compliant dynamics: Real-world planning assumes a rigid-grasp model; cloth and soft objects violate this. What learned or hybrid dynamics with compliance/uncertainty (and tactile feedback) can replace rigid assumptions?

- Safety and collision handling: Optimization accounts for smoothness and reachability but not explicit robot/environment collision constraints or safety margins. How to integrate fast collision checking and safety monitors into flow tracking?

- Closed-loop perception and replanning: Execution appears largely open-loop to a precomputed flow. There is no continuous state estimation of the real object during execution to servo to the flow and replan under disturbances.

- Uncertainty-aware planning: Uncertainty from video depth, tracking, and segmentation is not modeled or propagated. Can probabilistic MPC, robust optimization, or belief-space planning improve reliability?

- Dynamics model generalization: Particle vs. pose/heuristic dynamics are compared only on Push-T. Generalization across objects, contact regimes, and real-world variability, as well as data efficiency and coverage of the learned particle model, remain untested.

- RL reward generality: Flow-derived rewards are evaluated only on door opening in simulation. How well do such rewards scale to long-horizon, multi-stage tasks, deformable objects, and diverse embodiments on real hardware?

- Long-horizon sequencing: The method does not address chaining multiple subgoals, regenerating flows mid-execution, or hierarchical decomposition when video segments are short. How to compose and replan sequences of flows for long tasks?

- Real-time feasibility: End-to-end latency (video generation, depth estimation, tracking, optimization) and on-robot compute requirements are not reported. What is needed to achieve real-time closed-loop performance?

- Reproducibility and accessibility: Results depend on proprietary video models (e.g., Veo 3, Kling, Wan). Open-source substitutes, standardized prompts, and fair benchmarks are lacking.

- Camera-view alignment: The approach assumes known intrinsics/extrinsics and a viewpoint matching the generated video. How to handle viewpoint mismatch or handheld cameras via camera pose estimation and view synthesis?

- Multi-view sensing: Only single RGB-D is used. Whether multi-camera fusion or active perception reduces occlusion/tracking failures is unstudied.

- Language grounding verification: The system trusts the video model to interpret instructions; it lacks checks that the generated motion matches task semantics. Can intent verification and correction (e.g., via VLM critics) filter wrong generations?

- Failure recovery: There is no mechanism to detect mid-execution failure (missed grasp, drift from goal) and switch strategies, regenerate flows, or safely abort.

- Flow accuracy metrics: The paper lacks quantitative evaluation of reconstructed 3D flow against ground truth. Benchmarks and metrics for flow fidelity and temporal consistency are needed.

- Distractor robustness: Robustness to moving distractors, humans in scene, or cluttered backgrounds is not assessed.

- Point sampling and weighting: The number/placement of tracked points, confidence weighting, and adaptive resampling are not ablated; their impact on planning stability is unknown.

- Time scaling and speed control: The interface does not manage execution speed vs. video time; adaptive pacing to maintain contact feasibility and stability is missing.

- Force-aware manipulation: The approach is geometry-centric; tasks requiring force control (insertion, tight fits) are out of scope. How to fuse 3D flow with force/torque sensing and compliant control?

- Baseline coverage: Comparisons are limited to AVDC and a RIGVID variant. Stronger baselines (e.g., keypoint-, affordance-, or code/3D-value-map-based planners) and ablations (mask quality, depth model) are missing.

- Cross-embodiment transfer on hardware: While simulation shows cross-embodiment policies, real-world demonstrations across multiple embodiments are not provided; practical transfer remains open.

Glossary

- 3D object flow: A time-varying 3D trajectory field of object points that captures an object’s motion; used as an intermediate representation between video predictions and robot control. "Dream2Flow then extracts a 3D object flow from the motion in the video, allowing for downstream planning and execution with a robot across a wide variety of tasks."

- 3D scene flow: The per-point 3D motion field of an entire scene (often estimated from point clouds). "3D scene flow in point clouds"

- Action space: The set/parameterization of actions an agent can issue (e.g., joint torques, poses, or motion primitives). "due to the embodiment gap and hence the different action spaces."

- Affordance maps: Spatial maps predicting feasible interactions or uses of objects/regions for manipulation. "or affordance maps~\cite{tang2025uad}"

- Articulated: Refers to objects consisting of multiple rigid parts connected by joints, enabling relative motion. "including rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular."

- Camera extrinsics: The pose (rotation/translation) of a camera with respect to a world or robot frame. "a known camera projection Π (intrinsics and extrinsics to the robot frame)"

- Camera intrinsics: The internal calibration parameters of a camera (e.g., focal length, principal point). "a known camera projection Π (intrinsics and extrinsics to the robot frame)"

- Dense optical flow: Per-pixel 2D motion vectors between consecutive video frames. "computing dense optical flow between frames"

- Dynamics model: A function that predicts next states from current states and actions, used for planning or control. "Let f be a dynamics model"

- Embodiment gap: The mismatch between human motions in videos and the robot’s actuation/kinematics, complicating direct imitation. "overcomes the embodiment gap"

- End-effector: The robot’s tool tip or hand that interacts with objects (e.g., gripper, fingers). "We use absolute end-effector poses as the action space"

- Forward dynamics model: A predictive model that maps current state and action to the next state (or state change). "we learn a forward dynamics model that takes as input a feature-augmented particles"

- Foundation models: Large pre-trained models (e.g., in vision) used as general-purpose components in downstream tasks. "vision foundation models"

- Image-to-video model: A generative model that synthesizes a video sequence conditioned on an initial image (and often text). "an image-to-video model synthesizes video frames conditioned on the instruction."

- Kinematic constraints: Limitations imposed by the robot’s geometry and joint limits on feasible motions. "with respect to its kinematic and dynamic constraints"

- Language-conditioned: Conditioned on natural language instructions to guide perception, generation, or control. "reconstructing 3D object flow from language-conditioned generations"

- Non-prehensile manipulation: Manipulating objects without grasping, e.g., pushing or sliding. "For tasks involving non-prehensile manipulation"

- Object-centric: Focusing representations or objectives on specific objects rather than the whole scene or agent. "Object-centric alternatives rely on descriptors or keypoints to capture task-relevant structure"

- Open-world manipulation: Performing tasks in varied, unstructured environments with novel objects and goals. "for open-world manipulation"

- PDDL: The Planning Domain Definition Language, a formalism for specifying planning problems. "such as PDDL and temporal logics"

- Point tracking: Following specific pixels/points across frames to estimate their trajectories. "point tracking using vision foundation models"

- Potential fields: Scalar fields guiding motion via gradients, often used as heuristic navigation/manipulation objectives. "3D value maps akin to potential fields"

- Random shooting: A sampling-based planning method that evaluates many random action sequences to choose the best. "we use random-shooting"

- Reinforcement learning: Learning policies via trial-and-error to maximize cumulative reward. "Through trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning"

- Reward function: The scalar objective used in RL to evaluate and guide behavior. "The reward function used consists of one term"

- Rigid transforms: SE(3) transformations (rotation and translation) that assume shape rigidity. "solve for a sequence of rigid transforms of the relevant object"

- Rigid-grasp dynamics model: A model assuming the grasped part moves as a rigid body rigidly attached to the end-effector. "The rigid-grasp dynamics model assumes that the grasped part is rigid"

- Scale–shift ambiguity (monocular video): The inability to recover absolute scale and offset from monocular depth without external calibration. "Due to the scale-shift ambiguity of monocular video"

- Sensorimotor policy: A policy mapping sensory inputs directly to motor actions. "sensorimotor policies---the extracted object motion in 3D serves as the tracking goal for trajectory optimization or a reinforcement learning policy"

- Soft Actor-Critic (SAC): An off-policy RL algorithm that maximizes reward and entropy for stable, sample-efficient learning. "with SAC~\cite{haarnojaSAC2018}"

- Temporal logics: Formal languages for specifying temporal task constraints and sequencing. "temporal logics"

- Trajectory optimization: Computing action sequences by minimizing a cost subject to dynamics and constraints. "trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning"

- Trajectory tracking: Controlling a system to follow a desired time-parameterized path. "formulates manipulation as object trajectory tracking."

- Video depth estimation: Predicting per-frame depth from video, often with monocular cues and temporal consistency. "Video Depth Estimation:"

- Visuomotor policy: A policy that maps visual observations directly to motor commands. "language-conditioned visuomotor policies"

- Visual world models: Predictive models of future visual observations under actions for planning/control. "visual world models"

- Zero-shot: Performing tasks without task-specific training or demonstrations. "enables zero-shot guidance from pre-trained video models"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by integrating the paper’s off-the-shelf pipeline (video generation, segmentation, tracking, depth estimation, and planning/RL) into existing robotic systems and research workflows.

- Zero-shot execution of everyday manipulation tasks from text and a scene image

- Sectors: robotics, consumer/home, retail, logistics

- What it does: Execute tasks like “put bread in bowl,” “open oven,” “cover bowl,” and “open door” using only an RGB-D snapshot and a language instruction—no task-specific demos.

- Tools/products/workflows: Grounding DINO + SAM 2 for object localization/masking, CoTracker3 for point tracking, SpatialTrackerV2 for depth, 3D object flow reconstruction, PyRoki trajectory optimization or SAC-based RL policy for action; optional AnyGrasp for grasp proposals, HaMer for hand/part selection cues from video.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Still camera and correct calibration (intrinsics/extrinsics), adequate visibility (limited occlusion), reliable video generation (limited morphing/hallucination), rigid-grasp assumption for many tasks, available RGB-D.

- Intent-to-Action compiler for robots (ROS/MoveIt integration)

- Sectors: software, robotics

- What it does: A ROS 2 node/plugin that converts text (“open the top drawer”) plus an RGB-D snapshot into an executable motion plan via 3D object flow tracking.

- Tools/products/workflows: ROS 2 node wrapping video generation APIs (e.g., Wan/Kling/Veo), mask/track/depth modules, flow-to-plan via PyRoki or MoveIt controllers; export flows as task goals for planners.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Dependence on video generator API quality and latency; safety layers needed to validate planned motions; licensing for commercial video models.

- Cross-embodiment policy training using 3D object flow rewards

- Sectors: robotics, simulation/RL

- What it does: Train SAC (or similar) policies for different embodiments (e.g., Franka arm, Spot, GR1) using object-flow matching as reward—demonstrated comparable success to hand-crafted object-state rewards.

- Tools/products/workflows: Simulator (e.g., Robosuite), extracted 3D object flow trajectories as reward functions, policy training pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to a sufficiently faithful simulator; quality of extracted flow; transfer may require sim-to-real calibration.

- Rapid skill authoring from generated videos

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics, service robotics

- What it does: Convert video-imagined object motions into reusable skill primitives (e.g., open-handle, place-in-container) that can be parameterized per scene.

- Tools/products/workflows: Skill library builder that stores 3D object flows and associated grasp candidates (AnyGrasp), with parameterized end-effector trajectories optimized via PyRoki.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable grasp-part association (using HaMer heuristics), consistent object visibility during tracking.

- Visual safety envelope and motion compliance monitoring

- Sectors: robotics safety, policy/compliance, industrial automation

- What it does: Predict the path of target objects via 3D flow and ensure resultant motions don’t enter restricted zones or collide with humans/equipment.

- Tools/products/workflows: Safety module that checks planned object trajectories against geofences and forbidden volumes before execution.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate camera calibration and flow extraction; conservative margins to compensate for video artifacts and occlusions.

- Benchmarking/QA for video generation and perception stacks

- Sectors: academia, software tooling

- What it does: Use 3D object flow fidelity and downstream task success rates to compare video generators (Wan, Kling, Veo) and perception models (SAM 2, CoTracker3, SpatialTrackerV2).

- Tools/products/workflows: Flow-based metrics (e.g., visibility-weighted trajectory error), task success benchmarks across varied scenes/objects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Curated test scenes; standard evaluation procedures; controlled camera setup.

- Robotics education and rapid prototyping

- Sectors: education, academia

- What it does: Teach students to build end-to-end pipelines from language intent to robot action via 3D object flow, with ablations (e.g., particle vs pose dynamics).

- Tools/products/workflows: Classroom kits using RGB-D sensors, pre-integrated pipeline scripts, assignments on flow rewards and dynamics model comparisons.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accessibility of GPU/TPU resources for video generation; open model/tool licenses.

- In-store or showroom demo assistants

- Sectors: retail, customer experience

- What it does: Robots demonstrate product interactions (e.g., open appliances, arrange items) by compiling text prompts and scene snapshots into actions.

- Tools/products/workflows: On-site pipeline with guardrails and pre-approved prompts; human supervisor confirmation of flows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong safety and human-in-the-loop oversight; model reliability in new lighting/backgrounds.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, robustness improvements (multi-view depth, occlusion handling, better video generators), scaling, or standardization before widespread deployment.

- General-purpose home robots driven by a visual intent compiler

- Sectors: consumer robotics, daily life

- What it could do: Perform diverse household tasks (tidying, loading appliances, fetching, opening containers) via text prompts, with 3D object flow guiding strategies per scene.

- Potential products/workflows: “Dream2Flow Home” onboard stack with multi-camera depth, perception fusion, and learned dynamics; app-based prompt interface with safety validations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust multi-view tracking under occlusions, error detection/recovery, reliable grasp detection, improved video generators that avoid morphing/hallucination and model robot embodiments.

- Flexible industrial automation in unstructured environments

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics, warehousing

- What it could do: Zero-shot reconfiguration of lines for new SKUs; open/close articulated mechanisms; manipulate deformables and granular materials.

- Potential products/workflows: “Flow-to-Action Controller” integrated with industrial robot controllers; standardized 3D object flow goals for Task and Motion Planning (TAMP).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized interface/API for 3D object flow, certified safety modules, high reliability under varied lighting, clutter, and occlusions.

- Cross-embodiment manipulation transfer across robot fleets

- Sectors: robotics, enterprise operations

- What it could do: Share object-flow goals across heterogeneous robots (arms, mobile bases, humanoids), letting each embody different strategies to achieve the same object state change.

- Potential products/workflows: Fleet orchestration platform that distributes flow goals and aggregates success/feedback to refine policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consistent scene calibration across robots; unified flow formats; policy adaptation layers per embodiment.

- Foundation models for manipulation that leverage 3D object flow

- Sectors: software/AI, robotics

- What it could do: Train large world models that integrate video futures with flow-conditioned planners/policies for long-horizon tasks.

- Potential products/workflows: Pretrained “Flow-Conditioned Manipulation Model” combining generative video, multi-view flow, and dynamics; APIs delivering flows and action proposals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale datasets with accurate multi-view flow and action outcomes; compute budgets; standardized training/evaluation protocols.

- AR-guided programming by (virtual) demonstration

- Sectors: software, education, robotics integration

- What it could do: Users sketch or record interactions (in AR/VR) that are converted into 3D object flows and retargeted to real robots.

- Potential products/workflows: AR apps capturing object trajectories; alignment modules mapping virtual flows to physical scenes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust scene registration; calibration between AR and robot frames; accurate part/handle identification.

- Healthcare and assistive services

- Sectors: healthcare, eldercare, rehabilitation

- What it could do: Nurses’ aides and assistive robots perform non-invasive tasks (opening doors/drawers, fetching items, organizing supplies) from natural language requests.

- Potential products/workflows: Hospital logistics robots with strict safety envelopes and human-in-the-loop review; customized flows for medical devices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; rigorous safety validation; improved reliability under dynamic, crowded environments.

- Policy and standards for generative-model-guided robotics

- Sectors: policy/regulation, safety certification

- What it could do: Establish guidelines for using video generation and flow tracking in safety-critical systems—auditing, fail-safe procedures, liability frameworks.

- Potential products/workflows: Certification benchmarks using flow-based safety tests; audit trails storing intent, videos, flows, and executed actions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consensus on standards; transparent logging; privacy/data governance for videos of real environments.

- Standardized 3D object flow interface for task planning (TAMP)

- Sectors: robotics research/industry

- What it could do: Make 3D object flow a first-class goal specification in planners, enabling hybrid symbolic-geometric planning with flow-based objectives.

- Potential products/workflows: Open API/spec; MoveIt/TAMP plugins accepting flow targets; composable workflows where flows are chained across subtasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; clear interoperability with cost functions, constraints, and dynamics models.

- Robust multi-sensor flow extraction in-the-wild

- Sectors: robotics, perception

- What it could do: Use multi-view RGB-D/ToF/LiDAR and improved trackers to maintain flow under severe occlusion, fast motion, deformables, and transparent objects.

- Potential products/workflows: Sensor fusion pipelines; refractive flow modules for transparent objects; deformable and articulated flow reconstruction (building on DeformGS, RFTrans, etc.).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware upgrades; unified calibration; compute-efficient fusion; better model training data.

- “Dream2Flow Studio” and cloud services for skill generation at scale

- Sectors: software/SaaS, robotics platforms

- What it could do: Cloud platform to author, evaluate, and distribute flow-based skills from language prompts and scene captures; analytics on success/failure causes.

- Potential products/workflows: Web dashboard; dataset curation; enterprise APIs to push validated skills to fleets; continuous improvement via failure analysis.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Secure data handling; model licensing; cost-effective compute; strong MLOps and monitoring.

Note on feasibility: Across both immediate and long-term applications, success hinges on (1) reliability of video generation (reduced morphing, correct articulation axes, minimal hallucinations), (2) robust segmentation/tracking under occlusion and motion, (3) accurate depth calibration and camera stability, (4) appropriate dynamics models (particle-based models are crucial in some cases), (5) effective grasp selection, and (6) safety layers that validate planned object motions before execution. Improvements in these areas will broaden deployability and reduce failure modes.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.