Being-H0.5: Scaling Human-Centric Robot Learning for Cross-Embodiment Generalization

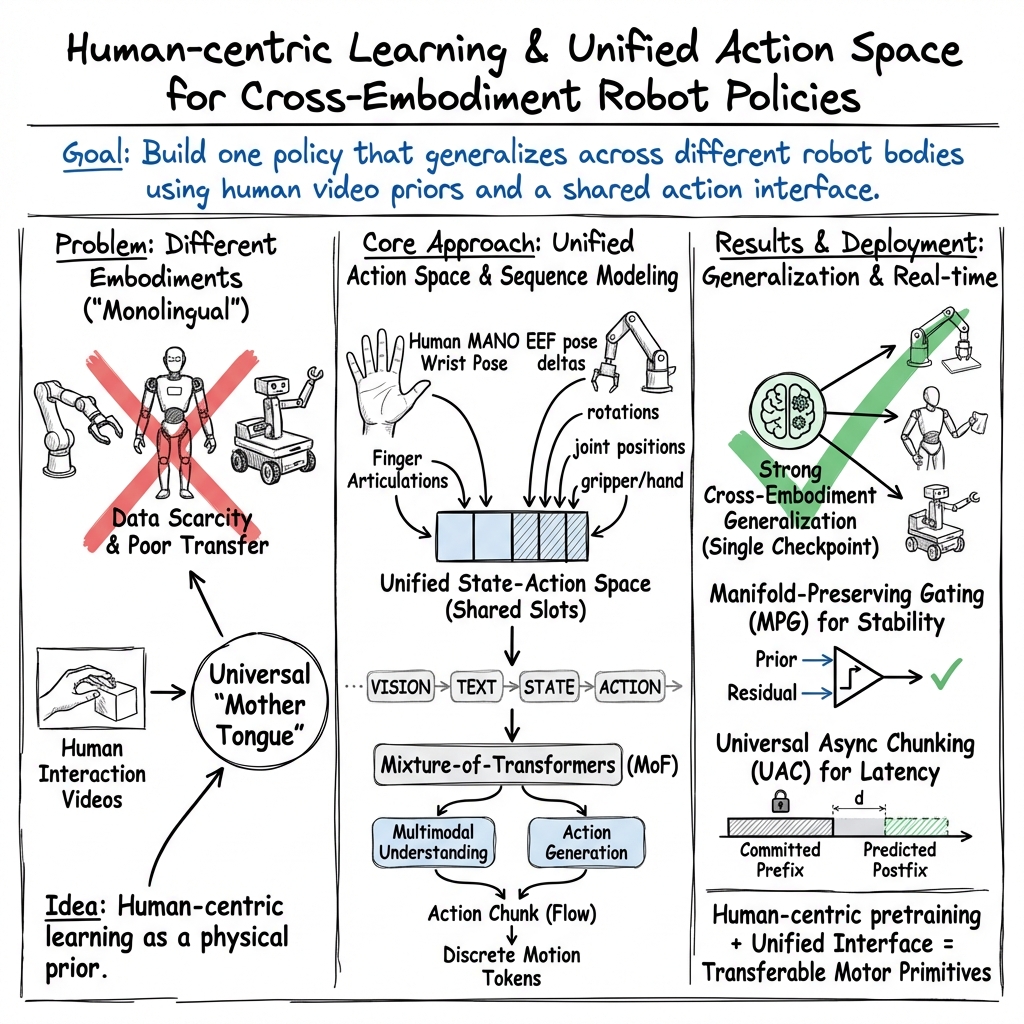

Abstract: We introduce Being-H0.5, a foundational Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model designed for robust cross-embodiment generalization across diverse robotic platforms. While existing VLAs often struggle with morphological heterogeneity and data scarcity, we propose a human-centric learning paradigm that treats human interaction traces as a universal "mother tongue" for physical interaction. To support this, we present UniHand-2.0, the largest embodied pre-training recipe to date, comprising over 35,000 hours of multimodal data across 30 distinct robotic embodiments. Our approach introduces a Unified Action Space that maps heterogeneous robot controls into semantically aligned slots, enabling low-resource robots to bootstrap skills from human data and high-resource platforms. Built upon this human-centric foundation, we design a unified sequential modeling and multi-task pre-training paradigm to bridge human demonstrations and robotic execution. Architecturally, Being-H0.5 utilizes a Mixture-of-Transformers design featuring a novel Mixture-of-Flow (MoF) framework to decouple shared motor primitives from specialized embodiment-specific experts. Finally, to make cross-embodiment policies stable in the real world, we introduce Manifold-Preserving Gating for robustness under sensory shift and Universal Async Chunking to universalize chunked control across embodiments with different latency and control profiles. We empirically demonstrate that Being-H0.5 achieves state-of-the-art results on simulated benchmarks, such as LIBERO (98.9%) and RoboCasa (53.9%), while also exhibiting strong cross-embodiment capabilities on five robotic platforms.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces Being‑H0.5, a new kind of robot “brain” that can see, read instructions, and move (a Vision‑Language‑Action model). Its big goal is to teach one model to work across many different robot bodies—small arms, two‑armed robots, and even humanoids—without starting over for each machine. To make that possible, the team builds a huge training set called UniHand‑2.0 and a “universal grammar” for robot actions so different robots can learn from the same examples, especially from human hand movements.

What questions were the researchers trying to answer?

- How can a robot quickly learn to use a new body (new arms, hands, speeds) without tons of new data?

- Can we use human videos and hand motions as a “mother tongue” of physical interaction that robots can learn from?

- Is there a way to represent actions so different robots “speak” the same action language?

- Can one model understand what it sees and reads, and then act, all in the same system?

- How do we keep robot behavior stable and safe when sensors are noisy or when robots operate at different speeds?

How did they do it?

A massive, human‑centric dataset: UniHand‑2.0

The team built one of the largest training collections for robot learning:

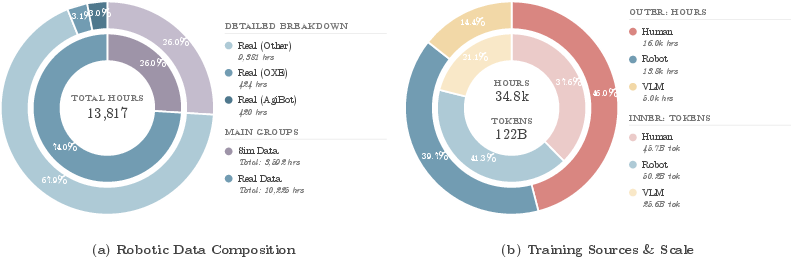

- Over 35,000 hours of data (about 400 million examples), including:

- 16,000 hours of first‑person human videos showing hands interacting with objects

- 14,000 hours of robot demonstrations from 30 different robot types

- About 5,000 hours’ worth of vision‑and‑text data to keep the model good at reading and reasoning

- Think of this as teaching the robot from both “human teachers” (videos of people using their hands) and “robot classmates” (many different robots doing tasks).

A Unified Action Space (a shared “alphabet” of moves)

Different robots have different controls—some have simple grippers, others have many moving fingers. The team designed a shared action space that maps all these different controls into common “slots” with the same meaning. Imagine teaching dance moves by meaning (“grasp gently,” “rotate wrist”) instead of by specific muscle movements—then any dancer (robot) can adapt the move to their own body.

One sequence for everything

They turn every type of data—videos, words, and actions—into one stream of small pieces (tokens), like words in a sentence. The model learns to:

- Read and answer questions (text tokens)

- Understand what it sees (vision tokens)

- Predict the next helpful move (action tokens) This way, perception, understanding, and action are trained together, not as separate parts.

A “team of experts” model: Mixture‑of‑Transformers + Mixture‑of‑Flow

The architecture separates higher‑level thinking from low‑level muscle control:

- General “reasoning” parts understand images and instructions.

- Specialized “action experts” focus on different bodies or motion styles. A router chooses which expert to consult for each situation, a bit like asking the right coach for a specific sport. “Flow” here means generating smooth, continuous motion, like planning a path your hand follows instead of jumping from point to point.

Stability and timing tricks

- Manifold‑Preserving Gating: When the camera view is unclear, the model leans more on safe, reliable motion patterns—like staying on the “safe roads” of movement rather than guessing wildly.

- Universal Async Chunking: Robots act at different speeds and have different reaction delays. The model learns to produce short chunks of actions that still work well even if a robot is fast, slow, or laggy—kind of like speaking in phrases that sound natural whether someone listens in fast‑forward or slow‑motion.

A better way to collect human data: UniCraftor

They built a portable recording system to capture high‑quality human demonstrations:

- Depth cameras for 3D information

- Precise camera positioning using AprilTags (QR‑like markers) and a math method to locate the camera exactly

- A foot pedal to mark the exact moments of important events (like “touch” or “release”) This yields cleaner, more accurate training signals for learning how hands truly interact with objects.

What did they find?

- Strong generalization across robots: One Being‑H0.5 model checkpoint controlled five very different robots (including Franka arms, a humanoid Unitree G1, and others) to do many tasks.

- State‑of‑the‑art test results: It scored 98.9% on LIBERO and 53.9% on RoboCasa, two well‑known robot simulation benchmarks, using only regular RGB video input.

- “Zero‑shot” transfer signals: The same model showed non‑zero success even on new robot‑task combinations it had never seen for that robot—like trying a new instrument for the first time and still playing a simple tune.

- Scalable training recipe: The unified action space and single sequence training let human data teach complex robots, reducing how much platform‑specific data is needed.

Why this matters:

- It proves that treating human movement as a universal “physical language” helps robots learn faster and adapt to new bodies.

- It shows one model can see, understand, and act together, rather than stitching separate systems.

What could this change?

- Faster deployment on new robots: Companies and labs could bring up new robot hardware with less custom data.

- More capable household and factory robots: Skills from one robot can spread to others, speeding up progress.

- Safer and more stable behavior: The model’s stability tricks help avoid weird or unsafe motions when sensors are noisy.

- Community progress: The team plans to open‑source models, training code, and real‑world deployment tools, lowering barriers for others to build on this work.

Key takeaways

Being‑H0.5 shows a practical path toward “one brain, many bodies” in robotics. By training on huge amounts of human hand videos and many different robots, using a shared action “grammar,” and designing a model that can think and move smoothly, the authors demonstrate strong, transferable robot skills—even across very different machines.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future work could address to strengthen, validate, and extend the paper’s claims.

- Unified Action Space specification: The paper does not formalize the unified action space (slot definitions, coordinate frames, units, invariances, and constraints). A clear algorithmic description, schema, and invertibility conditions for mapping human/robot controls into and out of this space are missing.

- Retargeting fidelity and kinematic mismatch: Quantitative analysis of retargeting error from MANO-derived human hand trajectories to diverse robot end-effectors (grippers, dexterous hands) is not provided, including sensitivity to differences in kinematics, reachability, compliance, contact friction, and force/torque limits.

- Action modality coverage: It remains unclear whether the unified action space supports torque/impedance control, force feedback, or haptic signals versus purely position/velocity control; the implications for contact-rich and compliance-critical tasks are unexplored.

- Mapping to non-anthropomorphic effectors: Generalization of human-centric action slots to non-hand tools (e.g., suction cups, scoops, specialized grippers) and to end-effectors with fundamentally different affordances is not evaluated or specified.

- Observation alignment and frames: How unified actions are grounded to object/world frames (absolute vs. relative commands, egocentric vs. exocentric coordinate choices) across datasets with unknown or inconsistent extrinsics is unspecified.

- Loss balancing and curriculum: The unified sequence modeling mixes text, human-motion, and robot-action losses, but the paper does not disclose loss weights, scheduling, or curriculum policies, nor ablate their effects on reasoning vs. control performance and cross-embodiment transfer.

- Mixture-of-Flow (MoF) design details: A precise architectural description (expert types, routing function, gating topology, training dynamics, regularization) and ablations comparing MoF to simpler baselines (single-flow head, MoE without flow, platform-specific heads) are absent.

- Manifold-Preserving Gating theory and validation: There is no formal definition or stability analysis of the gating mechanism, nor empirical stress tests to show it prevents off-manifold drift under perception ambiguity or distribution shift.

- Universal Async Chunking robustness: The method’s behavior under realistic latency/jitter, asynchronous sensing/control rates, and network delays is not quantified; stability and performance limits across embodiments with widely varying actuation profiles remain open.

- End-to-end latency and real-time throughput: Inference latencies, control frequencies, jitter statistics, and hardware requirements for real-time operation on high-DoF platforms are not reported, limiting reproducibility of low-latency claims.

- Emergent zero-shot transfer quantification: The “non-zero success rate” in cross-embodiment zero-shot is not characterized (absolute rates, tasks attempted, sample sizes, statistical significance, failure taxonomy), nor ablated to isolate contributing factors (data diversity vs. unified action vs. architecture).

- Safety and failure modes: The paper does not analyze failure cases (contact instability, object drop, self-collision, hardware stress) or detail safety constraints, safeguards, and recovery strategies during real-robot deployment.

- Sim-to-real mixture effects: While simulated data is capped at 26%, the impact of sim proportion on real-world performance, and techniques to mitigate domain gaps (randomization, dynamics calibration, vision realism), are not systematically studied.

- Depth/tactile benefits vs. RGB-only evaluation: The model is evaluated with low-resolution RGB, but the gains (or trade-offs) from adding depth, tactile, or multi-view inputs are not quantified—even though UniCraftor collects RGB-D and precise extrinsics.

- Dexterous manipulation coverage and metrics: The paper emphasizes dexterous hands but does not present task-specific dexterity benchmarks (precision pinch, in-hand rotation, tool use) or metrics (contact stability, slip, force control) demonstrating true high-DoF proficiency.

- Long-horizon planning evaluation: Although planning datasets are included, there is no closed-loop evaluation of long-horizon, multi-step tasks on real robots with metrics for plan correctness, subgoal sequencing, and recovery under partial failure.

- Multi-view fusion and calibration generality: UniCraftor relies on AprilTags for extrinsics; it remains unclear how the approach generalizes to tag-free environments, and how multi-view fusion is handled for datasets without reliable calibration.

- Human-video annotation reliability: The use of LLM-generated per-second and chunk-level annotations is not audited for consistency, correctness, or bias; the impact of annotation noise on policy learning and potential mitigation strategies are not reported.

- Hand pose estimation noise: Residual errors in HaWoR hand pose estimates (especially under occlusion, motion blur, and clutter) and their downstream effect on control policies are not quantified; robustness to estimate corruption remains untested.

- Data deduplication and downsampling: The 30% frame downsampling choice for robot data lacks analysis of temporal resolution trade-offs, especially for high-frequency control and contact events; impact on learning fine-grained dynamics is unknown.

- Scaling laws and data composition: There are no scaling-law analyses linking data size, embodiment diversity, and performance; optimal mixtures of human vs. robot data (and of sim vs. real) for target embodiments remain an open design question.

- Adaptation protocols for low-resource robots: The paper motivates rapid adaptation to new platforms but does not define or evaluate standardized few-shot/zero-shot adaptation protocols, data budgets, or fine-tuning strategies.

- Continual learning and catastrophic forgetting: How the model adapts to new embodiments or tasks without overwriting prior skills—especially balancing vision-language reasoning and action competence—remains unaddressed.

- Benchmark breadth and comparability: Evaluation focuses on LIBERO and RoboCasa and a limited set of real platforms; broader benchmarks (clutter, deformables, dynamic scenes, tool use) and standardized comparability (modalities, resolutions, action interfaces) are missing.

- Ethical, privacy, and licensing considerations: The paper does not discuss consent, privacy, and licensing issues around large-scale egocentric human data and third-party datasets, nor guidelines for safe open-source deployment on powerful robots.

- Generalization beyond manipulation: Although humanoids appear in the corpus, the unified action space’s applicability to locomotion, whole-body coordination, and mobile manipulation (navigation + manipulation) is not demonstrated.

- Resource and reproducibility details: Model size, training compute beyond “1,000 GPU-hours,” optimizer and hyperparameters, and exact data recipes are insufficiently detailed for full reproduction of reported results.

- Robustness to ambiguous or adversarial instructions: The model’s behavior under underspecified, conflicting, or adversarial language commands is not evaluated; safeguards and disambiguation strategies are unspecified.

- Failure analysis and debugging tools: There is no systematic framework for diagnosing cross-embodiment failures (mapping errors, perception issues, routing mistakes), nor tools for inspecting learned action slots or expert routing decisions.

Practical Applications

Below are actionable, real-world applications derived from the paper’s findings, methods, and innovations. Each item notes relevant sectors, potential tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

- Cross-embodiment skill deployment for heterogeneous robot fleets

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics, hospitality, retail, education

- What: Use a single Being-H0.5 checkpoint to run core manipulation tasks (pick-and-place, drawer/cabinet opening, tool use, wiping/cleaning) on different robots (e.g., Franka, Split ALOHA variants, Unitree G1, SO-101, PND Adam-U) with minimal robot-specific data.

- Tools/workflows: Being-H0.5 weights;

Unified Action Spaceadapter per robot;Universal Async Chunkingtiming profiles; real-time inference stack; ROS/MoveIt integration. - Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware drivers and calibrated kinematics; small adaptation set (hours–days) for new embodiments; safety envelopes and shutoffs; GPU for low-latency control.

- Rapid bootstrapping from human videos to robot policies

- Sectors: manufacturing, service robotics, R&D

- What: Train/fine-tune policies for new tasks by leveraging in-the-wild egocentric human video data aligned via MANO-derived hand motion; drastically reduce teleoperation demands.

- Tools/workflows: UniHand-2.0 sampling; HaWoR pose estimation; motion tokenization; unified sequence modeling pipeline; small task-specific fine-tuning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality and relevance of human videos; correct retargeting to target robot; privacy-compliant data sourcing.

- Low-cost data collection using UniCraftor

- Sectors: academia, startups, education

- What: Deploy the portable, modular RGB-D + AprilTag + foot-pedal kit to collect high-quality egocentric manipulation datasets with synchronized depth and interaction events.

- Tools/workflows: UniCraftor hardware bill-of-materials; AprilTag-based PnP calibration; multi-view D435; event-trigger annotations; Grounded-SAM2 + DiffuEraser post-processing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to egocentric recording environments; tag visibility; basic hardware assembly and calibration skills.

- Instruction-following manipulation via VLA

- Sectors: service robotics, education, smart labs

- What: Execute short-horizon tasks from natural language commands (e.g., “place the red bowl on the top shelf”), using Being-H0.5’s balanced visual-language grounding.

- Tools/workflows: Voice/GUI command interface; instruction parser; grounded 2D spatial cues (RefCOCO/RefSpatial) feeding the unified sequence; action head via MoF.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear prompts; reliable perception in target environment; object visibility and reachability; safety interlocks.

- Robust control under sensor shift

- Sectors: industrial automation, hospitals, warehouses

- What: Improve stability during lighting occlusions, motion blur, and camera offsets using manifold-preserving gating to fall back on reliable priors.

- Tools/workflows: MoF + gating configuration; health monitoring for perception confidence; fallback routines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Proper gating thresholds; coverage of relevant scenarios in pre-training; human-in-the-loop oversight for edge cases.

- Dexterous manipulation on accessible platforms

- Sectors: labs, small manufacturing, assistive tech prototyping

- What: Perform precise grasps, bimanual coordination, and tool handling with dexterous end-effectors (e.g., RMC RM65, PND Adam-U) using human-centric priors.

- Tools/workflows: Unified Action Space mapping for dexterous hands; chunked control; depth-aware perception cues.

- Assumptions/dependencies: End-effector capability and calibration; safe contact modeling; limited task complexity initially.

- Multi-robot education kits and curricula

- Sectors: education, makerspaces

- What: Teach cross-embodiment robotics using low-cost arms (SO-101, BeingBeyond D1) with an out-of-the-box VLA; students experiment with unified state-action tokens and timing profiles.

- Tools/workflows: Pre-built demos; notebook-based fine-tuning; simple ROS nodes; small datasets collected via UniCraftor.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Budget hardware; campus GPU access or cloud credits; classroom safety protocols.

- Unified benchmarking and reproducibility

- Sectors: academia, open-source ecosystems

- What: Standardize cross-embodiment evaluation using the model weights, training pipelines, and simulation scripts; compare LIBERO and RoboCasa performance across embodiments.

- Tools/workflows: Open-source recipe (~1,000 GPU-hours); dataset loaders for UniHand-2.0; evaluation harnesses; leaderboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licenses for datasets; compute availability; careful replication of timing and adapters.

- Fleet orchestration with embodiment-aware adapters

- Sectors: logistics, facility management

- What: Central controller dispatches tasks to heterogeneous robots with per-robot Unified Action Space adapters and per-site Async Chunking profiles.

- Tools/workflows: Scheduler; perception services; adapter registry; monitoring dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Network QoS; reliable local perception; collision avoidance and multi-agent coordination.

- Safety and compliance starter practices for egocentric data

- Sectors: policy, corporate governance, HR

- What: Implement privacy policies, consent workflows, and data minimization for head-mounted capture in workplace settings.

- Tools/workflows: Consent forms; anonymization pipelines; retention policies; DPO oversight.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal review; worker councils/IRBs; secure storage.

Long-Term Applications

- Embodiment-agnostic “universal” robot policy

- Sectors: consumer robotics, enterprise automation

- What: A single generalist model operating across many robot morphologies at home and work, with minimal per-robot configuration.

- Tools/products: “Skill app store” backed by Unified Action Space standards; cloud policy updates; adapter marketplace.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry-standardization of action-space interfaces; broad hardware support; large-scale post-training on diverse tasks.

- Programming by demonstration-at-scale

- Sectors: manufacturing, construction, laboratories

- What: Workers record egocentric demonstrations; systems convert to transferable skills usable by varied robots without expert teleoperation.

- Tools/workflows: Enterprise UniCraftor deployments; automated labeling; task library management; QA loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust retargeting for unusual tools/contexts; workflow integration; union and safety compliance.

- Assistive dexterous prosthetics and rehabilitation

- Sectors: healthcare, medtech

- What: Map human hand “mother tongue” motions to robot hands and prosthetics for precise manipulation and ADLs, leveraging Unified Action Space for intent transfer.

- Tools/products: Prosthetic controllers; patient-specific adapters; rehab training suites.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Medical-grade safety; tactile sensing integration; personalization; regulatory approvals.

- Humanoid generalists for facility operations

- Sectors: facilities, hospitality, healthcare

- What: Cross-embodiment VLAs extend to legged/humanoid platforms for diverse tasks (stocking, cleaning, basic assistance).

- Tools/workflows: Multi-modal planning; locomotion interfaces; MoF expert specialization per morphology.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable mobility and manipulation hardware; long-horizon planning; site mapping and safety.

- Cloud-native cross-robot orchestration services

- Sectors: software, robotics platforms

- What: Centralized “robot OS” that deploys and updates policies to fleets of heterogeneous robots, monitors performance, and adapts chunking/gating.

- Tools/products: Cloud inference; adapter registries; telemetry; A/B skill rollouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Edge compute; latency constraints; security; vendor ecosystem cooperation.

- Standardization of Unified Action Space as an industry API

- Sectors: standards bodies, robotics vendors

- What: Define a common action/state tokenization across embodiments to unlock portable skills and vendor-neutral interoperability.

- Tools/workflows: Working groups; open specs; compliance tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-vendor buy-in; IP considerations; alignment with ROS2/MoveIt ecosystems.

- High-fidelity tactile and multimodal integration

- Sectors: precision manufacturing, surgery, micro-assembly

- What: Extend the framework with tactile sensing, force feedback, and fine-grained contact modeling for delicate tasks.

- Tools/workflows: Sensorized end-effectors; multi-modal token streams; MoF experts for contact-rich actions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sensor availability; data scale; safe contact policies; sim-to-real transfer for contact dynamics.

- Emergency response and field robotics

- Sectors: public safety, defense, disaster relief

- What: Zero-/few-shot adaptation to unfamiliar platforms and scenes for inspection, manipulation, and basic triage tasks.

- Tools/workflows: Rapid adapter kits; language-driven tasking; remote supervision.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Harsh environment robustness; comms constraints; strict operational safety.

- Continual learning across embodiments

- Sectors: research, advanced automation

- What: Lifelong learning that aggregates experience across robots and sites, improving transfer and reducing data needs over time.

- Tools/workflows: Federated learning; on-robot logging; periodic consolidation; drift detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy-preserving aggregation; compute budgets; catastrophic forgetting safeguards.

- Policy and governance frameworks for egocentric data in workplaces

- Sectors: policy, labor, privacy

- What: Regulations and best practices for large-scale human-centric data collection, consent, anonymization, and downstream use in robotics.

- Tools/workflows: Auditable data pipelines; purpose limitation; independent oversight; standardized risk assessments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legislative processes; cross-jurisdiction alignment; stakeholder engagement.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Compute: Real-time control and large-scale pre-training require GPUs; edge acceleration reduces latency.

- Data quality: Successful transfer depends on representative, clean human/robot data; poor labels or non-manipulative segments degrade performance.

- Hardware diversity: New embodiments still need mapping into the Unified Action Space; adapter engineering is non-trivial.

- Safety: Physical deployment requires robust guardrails, fail-safes, and human oversight, particularly in unstructured environments.

- Licensing and openness: Access to model weights, training scripts, and dataset licenses governs adoption; vendor cooperation accelerates standardization.

Glossary

- Action-space interference: Conflicts arising when combining control signals from different embodiments, leading to noisy training or degraded performance. "Naively aggregating these datasets introduces action-space interference, where conflicting control signals generate significant noise."

- Affordance: The actionable properties of objects that suggest how they can be manipulated. "Hand-centric interaction traces expose fine-grained contact patterns, dexterous control strategies, and diverse object affordance."

- AprilTags: Fiducial markers used for robust pose estimation and calibration in vision-based systems. "We compute ground-truth camera poses via five tabletop AprilTags using Perspective-n-Point (PnP) algorithms."

- Autoregressive approaches: Methods that generate outputs token by token, conditioning each step on previous outputs. "Early initiatives typically adopt autoregressive approaches, discretizing continuous actions into tokens to align with VLM training objective."

- Bimanual manipulation: Coordinated control using two arms or hands to perform tasks. "existing policies remain either embodiment-specific specialists or ‘shallow generalists’ that struggle with high-DoF tasks, such as dexterous or bimanual manipulation."

- Camera extrinsics: The external parameters (position and orientation) describing a camera’s pose relative to a world frame. "precise camera extrinsics—modalities that are often absent but important in current benchmarks."

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning: A prompting strategy that encourages models to produce intermediate steps of reasoning before final answers. "Some approaches employ Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning to decompose long-horizon tasks."

- Chunked control: Generating and executing actions in temporally grouped segments for real-time control. "Universal Async Chunking to universalize chunked control across embodiments with different latency and control profiles."

- Control frequencies: The rates at which control commands are issued to actuators. "embodiment heterogeneity—the physical variance between human morphology and diverse robotic platforms with disparate kinematics, actuation limits, and control frequencies."

- Cross-embodiment generalization: The ability of a policy to transfer across different robot morphologies and hardware. "a foundational Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model designed for robust cross-embodiment generalization across diverse robotic platforms."

- Dexterous manipulation: Fine-grained control of multi-fingered hands to perform complex object interactions. "To address the complexities of high-dimensional bimanual coordination and dexterous manipulation, recent datasets like AgiBot World, RoboMIND/2.0, and RoboCOIN have emerged."

- Diffusion-based architectures: Generative models that iteratively refine noise into structured outputs, adapted here for action generation. "frameworks such as π0 and GR00T-N1 integrate diffusion-based architectures (e.g, flow matching) to generate high-frequency action chunks."

- Distribution shift: A mismatch between training and deployment data distributions that degrades performance. "suffers from severe distribution shift especially when encountering the high-dimensional vector fields of complex entities."

- Egocentric videos: First-person viewpoint recordings capturing human interactions from the actor’s perspective. "integrates 16,000 hours of egocentric human video."

- Embodiment heterogeneity: Variation in robot morphologies, kinematics, and control characteristics. "scaling generalist robotics is constrained by embodiment heterogeneity—the physical variance between human morphology and diverse robotic platforms with disparate kinematics, actuation limits, and control frequencies."

- End-effector: The terminal device on a robot (e.g., gripper or hand) that interacts with the environment. "treating the human hand as a universal template for all end-effectors."

- Flow matching: A training technique for generative models that learns a continuous flow from noise to data. "integrate diffusion-based architectures (e.g, flow matching) to generate high-frequency action chunks."

- Hand-eye calibration: Estimating the transformation between a camera and a robot’s coordinate system to align perception and actuation. "This approach, rooted in classical robotic hand-eye calibration, offers superior stability against head-motion jitter and sensor noise."

- High-DoF tasks: Control problems involving many degrees of freedom, requiring precise coordination. "‘shallow generalists’ that struggle with high-DoF tasks, such as dexterous or bimanual manipulation."

- Inpainting: Filling in or removing regions in images or videos to clean or alter visual content. "AprilTag regions are tracked and inpainted using Grounded-SAM2 and DiffuEraser to ensure visual cleanliness."

- Inverse kinematics: Computing joint configurations that achieve a desired end-effector pose. "retargeting 3D wrist and hand poses from egocentric videos to robot commands via inverse kinematics."

- Kinematics: The study of motion without considering forces, crucial for modeling robot joints and links. "embodiment heterogeneity—the physical variance between human morphology and diverse robotic platforms with disparate kinematics, actuation limits, and control frequencies."

- MANO parameters: A parametric 3D hand model used to represent articulated hand poses. "constructs a shared action space using MANO hand-model parameters."

- Manifold learning: Approaches that assume data lies on a low-dimensional manifold embedded in a higher-dimensional space. "From a manifold learning perspective, simple embodiments (e.g, parallel grippers) operate on a low-dimensional, smooth action manifold."

- Manifold-Preserving Gating: A gating strategy designed to keep action generation on a valid motion manifold under sensory uncertainty. "Manifold-Preserving Gating for robustness under sensory shift."

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): Architectures that route inputs to specialized expert networks to improve capacity and specialization. "Inspired by the principle of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE), we introduce a scalable architectural framework called Mixture of Flow."

- Mixture-of-Flow (MoF): An expert architecture for action generation that separates shared dynamics from embodiment-specific experts. "Being-H0.5 utilizes a Mixture-of-Transformers design featuring a novel Mixture-of-Flow (MoF) framework to decouple shared motor primitives from specialized embodiment-specific experts."

- Mixture-of-Transformers (MoT): An architecture that combines multiple transformer experts for different sub-tasks or modalities. "Being-H0.5 adopts a Mixture-of-Transformers (MoT) design that disentangles high-level multimodal reasoning from low-level execution experts."

- Motor primitives: Reusable low-level movement patterns that compose complex actions. "decouple the action module into foundational experts with shared dynamic knowledge and specialized experts that utilize embodiment-aware task routing."

- Multimodal token stream: A serialized sequence that interleaves tokens from different modalities (vision, language, actions). "we serialize them into a single multimodal token stream, where vision and text provide contextual grounding and unified state/action tokens carry physically meaningful interaction signals."

- Negative transfer: When knowledge learned from one domain harms performance in another. "This often results in negative transfer, where cross-platform training degrades performance rather than fostering synergy."

- Next-token prediction loss: The standard autoregressive objective of predicting the next token in a sequence. "text-centric corpora ... contribute a standard next-token prediction loss over text."

- Perspective-n-Point (PnP): Algorithms that estimate camera pose from known 3D points and their 2D projections. "using Perspective-n-Point (PnP) algorithms."

- Proprioceptive-aware reasoning: Incorporating a robot’s internal sensing (e.g., joint states) into reasoning for better control. "Without reconciling these configurations, models fail to develop proprioceptive-aware reasoning."

- Retargeting: Mapping human motions or poses to robot commands while respecting kinematic constraints. "retargeting 3D wrist and hand poses from egocentric videos to robot commands via inverse kinematics."

- Sim-to-real gap: Performance differences between simulated training and real-world deployment. "While synthetic data offers scalability, it suffers from the persistent sim-to-real gap."

- Unified Action Space: A shared representation that aligns heterogeneous robot controls and human motions into common semantic slots. "we propose a Unified Action Space that maps human trajectories and heterogeneous robot controls into semantically aligned slots."

- Universal Async Chunking: A method to make chunked action policies robust across platforms with different timing and latency. "Universal Async Chunking to universalize chunked control across embodiments with different latency and control profiles."

- Vector field: A function assigning a vector (e.g., direction of change) to each point in a space, used here to model action evolution. "it must infer a continuous vector field to define the probabilistic evolution toward the next action state."

- Vision-Language-Action (VLA): Models that jointly process visual and textual inputs to produce physical actions. "We introduce Being-H0.5, a foundational Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model designed for robust cross-embodiment generalization."

- VQ-VAE tokens: Discrete latent codes produced by Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoders, used as compact action representations. "LAPA employs VQ-VAE tokens derived from frame pairs to pre-train a VLM, which is subsequently fine-tuned with an action head."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.