Cosmos Policy: Fine-Tuning Video Models for Visuomotor Control and Planning

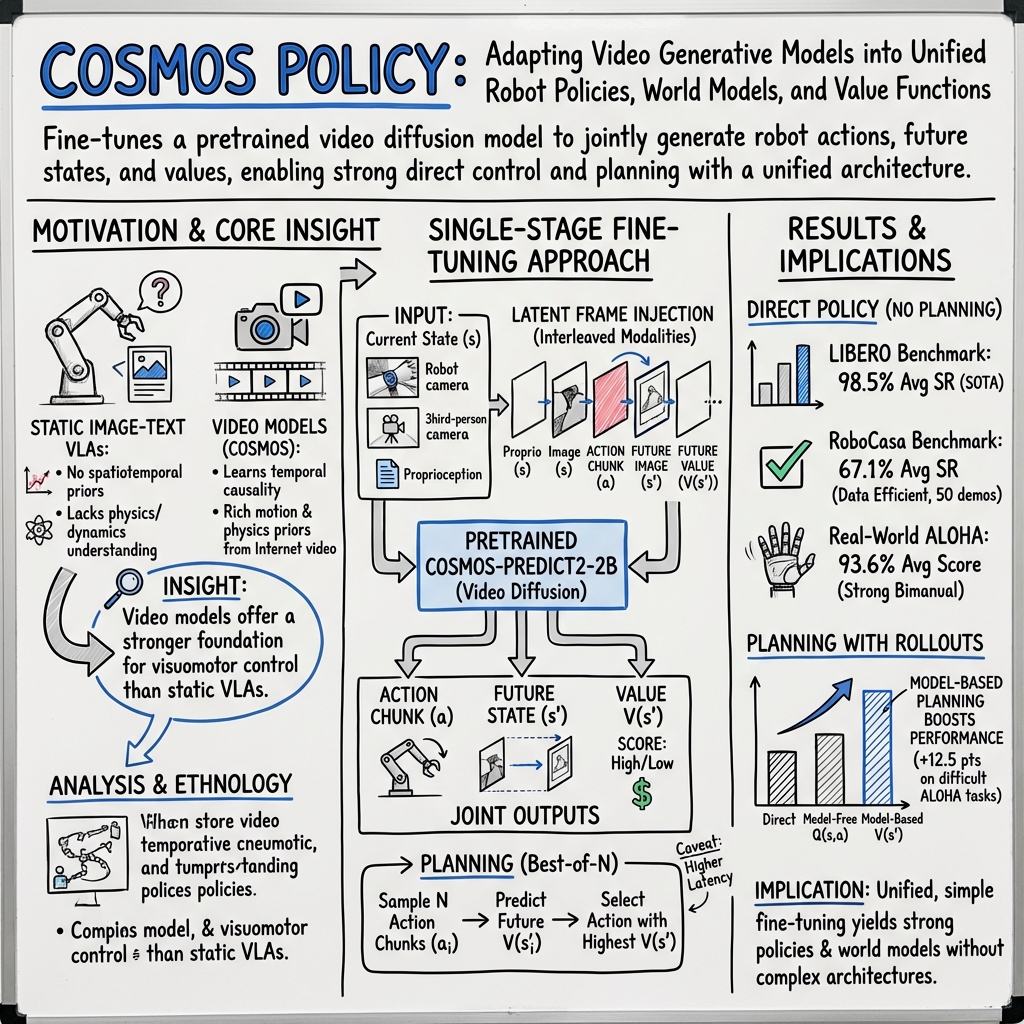

Abstract: Recent video generation models demonstrate remarkable ability to capture complex physical interactions and scene evolution over time. To leverage their spatiotemporal priors, robotics works have adapted video models for policy learning but introduce complexity by requiring multiple stages of post-training and new architectural components for action generation. In this work, we introduce Cosmos Policy, a simple approach for adapting a large pretrained video model (Cosmos-Predict2) into an effective robot policy through a single stage of post-training on the robot demonstration data collected on the target platform, with no architectural modifications. Cosmos Policy learns to directly generate robot actions encoded as latent frames within the video model's latent diffusion process, harnessing the model's pretrained priors and core learning algorithm to capture complex action distributions. Additionally, Cosmos Policy generates future state images and values (expected cumulative rewards), which are similarly encoded as latent frames, enabling test-time planning of action trajectories with higher likelihood of success. In our evaluations, Cosmos Policy achieves state-of-the-art performance on the LIBERO and RoboCasa simulation benchmarks (98.5% and 67.1% average success rates, respectively) and the highest average score in challenging real-world bimanual manipulation tasks, outperforming strong diffusion policies trained from scratch, video model-based policies, and state-of-the-art vision-language-action models fine-tuned on the same robot demonstrations. Furthermore, given policy rollout data, Cosmos Policy can learn from experience to refine its world model and value function and leverage model-based planning to achieve even higher success rates in challenging tasks. We release code, models, and training data at https://research.nvidia.com/labs/dir/cosmos-policy/

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper shows a simple way to turn a powerful video-making AI into a smart robot controller. The idea is to fine-tune a large video model so a robot can:

- choose its next moves,

- imagine what the world will look like after those moves,

- and estimate how good that future is.

By doing this, the robot can either act directly or plan ahead by “imagining” different futures and picking the best move.

What questions did the paper ask?

To guide readers, here are the main questions the authors wanted to answer:

- Can a big, pretrained video model be turned into a strong robot policy with just one fine-tuning step?

- Can we make that same model predict actions, future camera views, and a “score” for those futures at the same time?

- Does planning using these imagined futures improve success on hard tasks?

- How does this approach compare to other top robot control methods in simulations and the real world?

How did they do it? Methods and ideas in everyday language

Starting point: A video model that understands motion

The team started with a large video model called Cosmos-Predict2. Think of it as an AI that’s good at predicting how scenes change over time in videos. It has learned patterns like “if you push a cup, it moves” or “a hand reaching towards an object tends to grasp it.” That “sense of motion and physics” is valuable for robots.

Two key pieces this model uses:

- A video “compressor” (a VAE): It shrinks frames into small codes called “latents,” kind of like zipping a video into compact blocks.

- Diffusion learning: Imagine adding random noise to a picture and training a model to remove the noise to recover the clean image. Do this repeatedly, and the model gets really good at making realistic frames. Here, the model learns to “denoise” sequences of these compact codes.

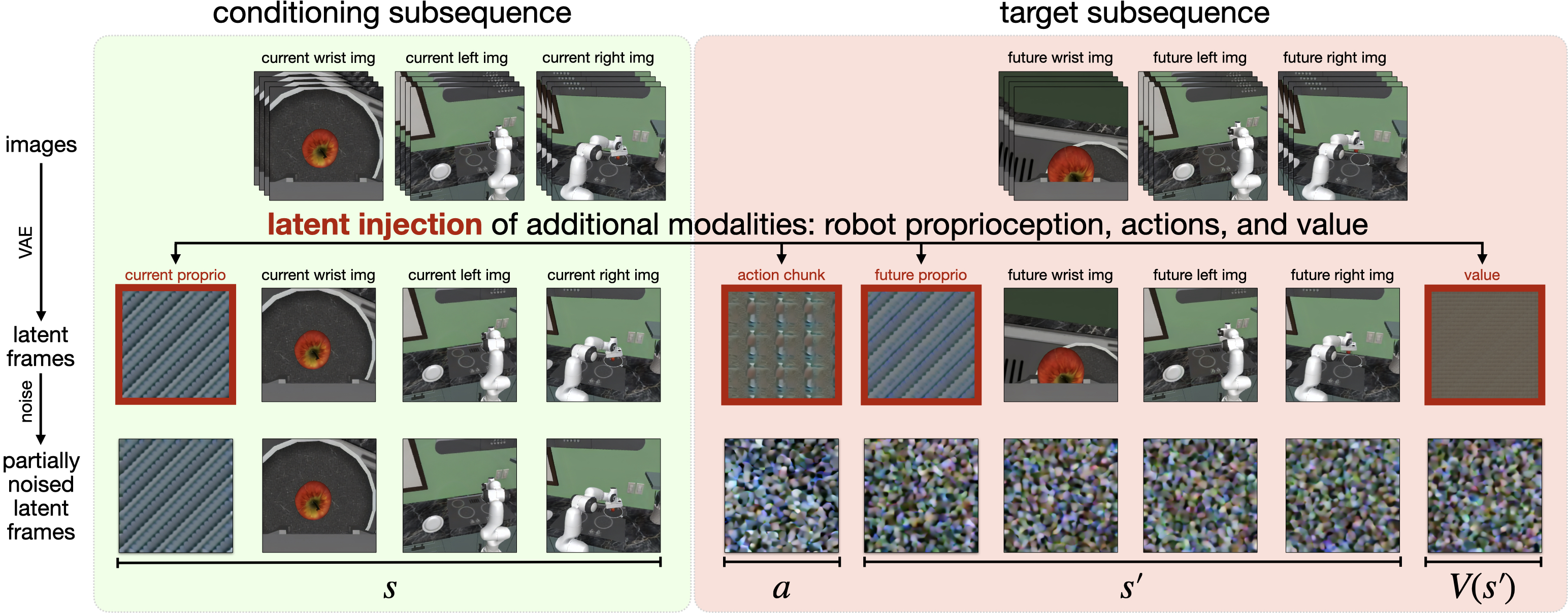

Turning a video model into a robot policy with latent frame injection

Robots need to handle more than just pictures: they also have body sensors, actions to take, and a way to judge how good a state is. The authors didn’t change the model’s architecture. Instead, they cleverly fed these extra robot signals into the model as if they were additional frames in the “compressed video.”

Analogy: Picture a flipbook. Normally, only images go in. Here, the authors slip in special “note cards” alongside the pictures:

- Robot’s body reading (“proprioception”), like joint angles or end-effector position.

- An “action chunk,” which is a short sequence of moves the robot will do next.

- Future images the robot expects to see after the action.

- A “value,” a score estimating how good that future is (higher means closer to success).

By inserting these “note cards” among the image frames, the model learns to treat actions and scores like part of the video story. This takes advantage of the model’s skill at modeling complex, time-based sequences.

Training the model

- Demonstrations: The robot learns from example runs showing what to do, like “place object on plate” or “fold a shirt.” These teach the policy to predict actions that lead to success.

- Rollouts (the robot’s own experiences): The robot tries tasks, sometimes fails, and records what happened. These help the model learn a more realistic “world model” (an internal simulator of what the next state will look like) and a better “value function” (how good a state is).

They jointly train the model so it learns three things together:

- The policy: choose actions given the current state.

- The world model: predict the future state after an action.

- The value: estimate how good that future state is.

Because the model learns all three at once inside the same “latent flipbook,” it stays simple—no extra modules or complex multi-stage pipelines.

Using the model: direct control vs. planning

There are two ways to use Cosmos Policy:

- Direct policy: The robot just picks the next action chunk and executes it.

- Planning: The robot samples several candidate action chunks, “imagines” the resulting future images and scores, and chooses the action leading to the highest predicted score. This is like trying multiple mini-plans in its head and picking the best one.

To make planning more reliable, they:

- Predict multiple times and average results in a robust way to handle uncertainty.

- Use parallel GPUs to speed up trying several options at once.

Simple definitions of key terms

- Proprioception: The robot’s sense of its own body, like joint angles and gripper state.

- Action chunk: A short sequence of moves executed together for smoother motion.

- World model: The robot’s “imagination” of how the world will look after an action.

- Value function: A score estimating how good a future is (closer to success = higher).

- Latent frames: Compact representations of images or signals used by the video model.

- Diffusion: A method where the model learns to turn noisy inputs back into clean ones.

Main findings and why they matter

Here are the standout results:

- In the LIBERO simulation benchmark, Cosmos Policy reached about 98.5% average success, setting a new state of the art.

- In the RoboCasa kitchen benchmark, it achieved about 67.1% average success using only 50 human demos per task, beating many methods that used much more training data.

- On real robots (ALOHA platform) in tough bimanual tasks like folding shirts or placing candies into a bag, Cosmos Policy had the highest overall score among strong baselines.

- Planning improves performance on the hardest tasks: adding model-based planning boosted success by roughly 12.5 points in difficult real-world scenarios.

Why this is important:

- It shows that video models’ “sense of motion and physics” can be reused for robot control with minimal changes.

- The approach is simple and unified: one model does actions, future prediction, and scoring.

- It works well in both simulated and real-world tasks, including long, precise, and multimodal manipulations.

Extra insights:

- Training from scratch (without the video model’s prior knowledge) performed noticeably worse. Starting from a pretrained video model matters.

- Teaching the policy to also predict future states and values (not just actions) helped performance.

- For planning, using the world model to predict the future state and then scoring that state (the V(s’) approach) worked better than directly predicting action scores (the Q(s,a) approach) when data was limited.

Implications and future impact

This research suggests a practical path for building strong robot policies:

- Use big video models as a foundation. They already understand motion and cause-and-effect from countless videos.

- Keep the system simple. Instead of creating extra action networks, inject robot signals into the model’s “video” sequence.

- Plan when needed. Imagining futures and picking the best move can turn near-misses into successes on hard tasks.

Potential impact:

- Faster development of reliable robot manipulation policies for homes, labs, and factories.

- Better performance with fewer training demonstrations, making robot learning more accessible.

- A foundation for more advanced planning, like imagining longer futures or deeper decision trees.

Current limitations and future work:

- Planning is slower than direct control and can take seconds per action chunk; speeding this up would help with fast-moving tasks.

- Getting good at planning requires enough rollouts; learning from fewer experiences would make the method easier to use.

- Extending the planning horizon (imagining further into the future) and improving search strategies could make robots even more capable.

In short, Cosmos Policy shows that we can turn a video-making AI into a powerful, practical robot brain that both acts and plans—by treating actions and goals as part of the “video story” the model already knows how to tell.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, framed to guide future research directions.

- Planning speed and latency: Model-based planning currently takes ~5 seconds per action chunk; how to reduce inference time (e.g., fewer diffusion steps, distillation, caching, model pruning/quantization, speculative decoding) without degrading success rates is unresolved.

- Limited planning horizon: Planning searches only one action chunk ahead and executes the full chunk; extending to receding-horizon control, multi-step tree search, or deeper horizons (and quantifying benefits vs. compute) remains unexplored.

- Reliance on rollout data for planning: Effective world model/value learning requires “substantial” rollout data; sample-efficiency, minimal data requirements, and active/on-policy data collection strategies are not quantified.

- Partial observability and no temporal context: The policy/world model use single-step observations (no input history) and predict only one future step (t+K); whether adding temporal context (e.g., recurrent memory, transformers over history) improves robustness under occlusion and complex dynamics is unknown.

- Latent frame injection design: Proprioception, action chunks, and values are inserted by tiling normalized scalars into full latent volumes; the optimality of this representation is untested. Investigating learned encoders/adapters for non-visual modalities, compact tokenization, and cross-modal alignment is needed.

- Sensitivity to modality ordering and layout: The injected sequence ordering (s, a, s′, V(s′)) is fixed; the sensitivity of performance to ordering, spacing, or mixing with image latents has not been studied.

- Multi-view generalization: Additional cameras are handled by simple interleaving; robustness to variable numbers of cameras, moving cameras, camera dropout, and viewpoint changes is not evaluated.

- Action representation and chunking: The effects of different action spaces (joint vs. Cartesian, force/torque), variable chunk lengths, and adaptive chunking policies (especially for dynamic or contact-rich tasks) are not analyzed.

- Full-chunk execution risks: Committing to an entire chunk without mid-chunk replanning may reduce safety/reactivity; strategies for chunk subdivision, interrupts, or guard conditions are not explored.

- Sparse reward dependence: Value learning uses sparse terminal rewards and Monte Carlo returns; handling dense/shaped rewards, bootstrapping, off-policy value learning, and reward design/measurement in real-world settings is left open.

- Observation versus latent “state” modeling: The “world model” predicts future observations, not latent state; the fidelity, consistency, and physical plausibility of multi-step predictions (beyond t+K) and metrics to evaluate them are not provided.

- Value prediction calibration: No assessment of calibration (e.g., reliability diagrams, Brier scores) is given; integrating uncertainty estimation (variance-aware selection, risk-sensitive planning) remains unexplored.

- Ad-hoc ensemble aggregator: The “majority mean” aggregator (3× world model, 5× value per action, fixed threshold) lacks justification; sensitivity analysis and principled uncertainty-weighted aggregation are missing.

- Model-free planning underperformance: The Q(s, a) variant underperforms with limited rollouts; improving model-free value learning (e.g., double Q, distributional RL, conservative updates, contrastive estimators) is an open direction.

- Parallel vs. autoregressive decoding trade-offs: The quality-speed trade-off between parallel joint decoding and autoregressive decoding is not quantified across tasks; guidelines for when to prefer each mode are absent.

- Scaling laws and data efficiency: The paper claims data efficiency (e.g., RoboCasa 50 demos) but does not present scaling curves vs. model size, training steps, or demonstration/rollout counts; controlled studies are needed.

- Cross-embodiment transfer: Generalization to different robot morphologies, effectors, and control interfaces (single-to-multi arm, mobile manipulation) is not evaluated.

- Dynamic/high-frequency tasks: Performance under high-speed, dynamic manipulation (e.g., catching, tool use) is unknown, especially given current planning latency and 25 Hz control.

- On-robot compute constraints: The 2B model’s memory/compute demands and feasibility on embedded hardware are not discussed; compression/distillation to lightweight policies is an open need.

- Safety and smoothness: From-scratch training produced jerky motions; general safety metrics, motion smoothness constraints, and safe learning mechanisms (e.g., action filters, barrier functions) are not analyzed.

- Dependence on proprietary pretraining: The approach relies on Cosmos-Predict2-2B; replicability with open-source video backbones and sensitivity to backbone choice are unaddressed.

- Benchmark comparability: RoboCasa comparisons mix methods trained with vastly different dataset sizes; fair, controlled studies at matched data scales (including scaling Cosmos Policy to larger datasets) are missing.

- Robustness under domain/style shift: While RoboCasa includes style shifts, systematic analysis of robustness to lighting, textures, and sensor noise (and how rollout-based fine-tuning mitigates these) is absent.

- Batch weighting and curriculum: The chosen training batch splits (50/50 for demos/rollouts; 90/10 during planning fine-tuning) are heuristic; exploring curricula, dynamic weighting, or multi-objective optimization is unstudied.

- Failure mode analysis: Beyond a few qualitative examples, there is no systematic taxonomy of failure modes or attribution (perception vs. action vs. planning) to guide targeted improvements.

- Theoretical grounding of injection approach: There is no formal analysis of why latent diffusion priors should optimally represent actions/values as frames; theoretical characterization or alternative formulations (e.g., conditional diffusion heads) remains open.

- Generalization across more task families: Planning benefits are demonstrated on two ALOHA tasks only; evaluating across diverse tasks (deformables, tool-use, long-horizon assembly) and reporting where planning helps/hurts is needed.

- Continual/online learning: The dual-deployment scheme fine-tunes on a static rollout set; mechanisms for safe, continual on-robot learning with drift detection and retention (avoiding catastrophic forgetting) are not explored.

- Automatic reward/score estimation: Real-world value labels rely on episode outcomes/percent completion; methods for automatic, reliable reward inference (e.g., via vision-language scoring or self-supervised signals) are unresolved.

- Robust language conditioning: The role and robustness of textual conditioning (ambiguous instructions, compositional goals, multi-step language) are not deeply examined; error cases and improvements (prompting, grounding) are open.

- Multi-sensor fusion beyond cameras: Integrating tactile/force sensing, audio, or proprioceptive dynamics models to resolve occlusions and improve contact prediction is unaddressed.

- Tree search and MPC integration: Combining the learned world model with classical planners (MPC/MPPI, CEM) or hybrid search-guided diffusion policies is left unexplored.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are specific, deployable use cases that can be built now by leveraging the paper’s findings (single-stage fine-tuning of a pretrained video model via latent frame injection, unified policy/world-model/value training, multi-view inputs, action-chunk control) and the released code/models.

- Bold: Rapid adaptation of manipulation policies for existing robot cells — Sector: Manufacturing, logistics, e-commerce — Tools/Products/Workflows: One-stage fine-tuning of Cosmos-Predict2-2B into a site-specific policy using 50–500 teleoperated demonstrations; integrate multi-view cameras and wrist cams via latent frame injection; deploy “direct policy” (no planning) for fast inference; optional value prediction for confidence gating; ROS2/Isaac integration — Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to the released checkpoints and tokenizer (Wan2.1); 1–4 GPUs for training/inference; reliable teleop data; calibrated multi-camera rig; safety interlocks for shared workcells

- Bold: Bimanual packaging and kitting (e.g., opening zip bags, placing items into containers) — Sector: E-commerce fulfillment, retail returns, lab kitting — Tools/Products/Workflows: Fine-tune on short, task-specific demos; deploy 2-second action chunks at ~25 Hz; use predicted V(s′) as a quality gate; optionally enable planning only for hard steps where added latency is acceptable — Assumptions/Dependencies: Two-arm platforms with simple grippers; cycle-time tolerance for occasional slower, planned moves; fixtures that reduce occlusion; small set of item geometries similar to training

- Bold: Deformable object handling (folding shirts/towels, bag manipulation) — Sector: Apparel logistics, laundry/returns processing, recycling — Tools/Products/Workflows: Collect ~10–100 demos per garment class; multi-view placement to reduce self-occlusion; direct policy for most steps; best-of-N planning for precise substeps (e.g., grasp edges, align folds) — Assumptions/Dependencies: Moderate throughput requirements; careful lighting/camera placement; diverse demos to cover fabric variability

- Bold: Small-object placement and containerization in labs — Sector: Biotech/pharma/diagnostics lab automation — Tools/Products/Workflows: Policies trained to pick/place consumables (tips, tubes, candies-like objects) into racks/bowls; leverage value predictions to trigger human-in-the-loop review for uncertain actions; slower “planned” sequences for high-stakes steps — Assumptions/Dependencies: Appropriate end-effectors; cleanroom compliance; compatible motion controllers; acceptance of lower speed in critical moments

- Bold: On-robot continual improvement via rollout learning — Sector: All robotized operations — Tools/Products/Workflows: Log trajectories and outcomes from live runs; periodically fine-tune a “planning model” with heavier world-model/value weights; dual-deploy (policy model for control, planning model for evaluation/search); best-of-N sampling with ensemble “majority mean” aggregation — Assumptions/Dependencies: MLOps for data/versioning; governance to safeguard data; compute budget for periodic updates; validation gates before redeploy

- Bold: Multi-camera retrofits without architecture changes — Sector: Robotics system integration — Tools/Products/Workflows: Add overhead/wrist views using latent frame injection; re-fine-tune on the same demonstrations with the new view configuration; no custom encoders needed — Assumptions/Dependencies: Camera sync and calibration; retraining to condition on new views; stable tokenizers/codecs

- Bold: Confidence-aware execution using value predictions — Sector: Manufacturing/logistics operations; safety/governance — Tools/Products/Workflows: Use predicted V(s′) as a risk/confidence metric to gate task progression or handoff to human; set task-specific thresholds; log low-confidence events for retraining — Assumptions/Dependencies: Calibration of value outputs to success probabilities; periodic re-tuning under distribution shift

- Bold: Academic benchmarking and teaching — Sector: Academia/education — Tools/Products/Workflows: Use released code/checkpoints to reproduce LIBERO and RoboCasa SOTA; run ablations (auxiliary targets, from-scratch training); explore Q(s, a) vs V(s′) planning; extend to new sensors via latent injection — Assumptions/Dependencies: GPUs; access to benchmark simulators and a robot (e.g., ALOHA or Franka) for lab classes; adherence to dataset licensing

Long-Term Applications

The following use cases require further research, scaling, or engineering (e.g., lower-latency planning, deeper search, broader generalization, certification).

- Bold: Real-time model-based planning with deeper lookahead — Sector: High-throughput manufacturing, mobile manipulation, dynamic pick-and-place — Tools/Products/Workflows: Distillation of best-of-N planning into fast policies, trajectory-level search trees, longer-horizon video-conditioned prediction, optimized inference stacks and accelerators — Assumptions/Dependencies: Significant algorithmic speedups and/or specialized hardware; robust horizon extension of the world model

- Bold: Cross-domain generalist manipulators with few-shot site adaptation — Sector: Robotics OEMs/platform providers — Tools/Products/Workflows: Pretraining on large-scale internet videos; latent injection for new modalities; rapid, few-shot fine-tuning per facility/task; policy marketplace for downloadable skills — Assumptions/Dependencies: Licensing/data governance for internet-scale corpora; embodiment gaps between videos and robots; safety under broad generalization

- Bold: Healthcare-grade assistants and surgical support — Sector: Healthcare/medical devices — Tools/Products/Workflows: Precision manipulation with model-based planning; teleoperation-to-autonomy pipelines; value-based gating and verification; procedural task libraries — Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulatory approvals (e.g., FDA); rigorous verification/validation; sterile hardware; near-zero failure tolerance and low-latency control

- Bold: Agricultural manipulation in unstructured outdoor environments — Sector: Agriculture/food production — Tools/Products/Workflows: Multi-view rigs on mobile platforms; planning under occlusion and motion; multimodal grasp strategies learned from few demos per crop type — Assumptions/Dependencies: Robustness to weather/lighting; moving/fragile targets; ruggedized hardware; real-time planning advances

- Bold: Autonomous self-improving robot fleets (closed-loop learning) — Sector: Warehousing/logistics/manufacturing — Tools/Products/Workflows: Fleet-scale rollout collection, federated model updates, automatic data curation, uncertainty/score-based deployment gates, continuous evaluation dashboards — Assumptions/Dependencies: Mature MLOps; privacy/security policies; rollback strategies; standardized telemetry

- Bold: Safety and compliance standards for foundation-model robot policies — Sector: Policy/regulation/insurance — Tools/Products/Workflows: Benchmarks with OOD stress tests; standards for rollout logging and audit trails; certification protocols using value-based risk thresholds; incident reporting schemas — Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder coordination (vendors, regulators, insurers); transparency on training data and model behavior

- Bold: Digital twins powered by learned world models — Sector: Industrial automation, energy, construction — Tools/Products/Workflows: Couple learned world models with simulators to generate synthetic rollouts, perform offline planning, and validate cell designs before deployment — Assumptions/Dependencies: High-fidelity sim-to-real transfer; domain randomization; methods to detect and correct model bias

- Bold: Privacy-preserving, personalized home assistance — Sector: Consumer robotics/eldercare — Tools/Products/Workflows: On-device few-shot fine-tuning from user demonstrations; continual personalization with local rollouts; value-based safety gating with user-defined risk settings — Assumptions/Dependencies: Edge compute with strong accelerators; privacy/legal frameworks; affordable, safe bimanual platforms; intuitive demo UIs

- Bold: Education platforms and competitions around video-model robotics — Sector: Education/skill development — Tools/Products/Workflows: Low-cost kits using Cosmos-like policies; standardized tasks/datasets; course modules on video priors for control and planning — Assumptions/Dependencies: Affordable hardware and cloud credits; open licensing for models/datasets; teacher training and curricula

Notes on general feasibility:

- Immediate deployment is best suited to semi-structured, moderate-speed cells where direct policies already achieve high success and planning latency (≈5 s per action chunk) is acceptable only for occasional critical steps.

- Long-term applications hinge on: faster planning, extended prediction horizons, reliable value calibration under distribution shift, robust multi-view setups, and standardized MLOps/safety practices.

Glossary

- Action chunk: A fixed-length sequence of low-level control commands emitted together to improve smoothness and efficiency. "predicts (1) a robot action chunk, (2) future state (represented by robot proprioception and image observations), and (3) value (expected rewards-to-go at the future state)."

- Adaptive layer normalization: A normalization mechanism conditioned on an external variable (e.g., noise level) to modulate network activations. " conditions on via cross-attention and on via adaptive layer normalization"

- Autoregressive decoding: Generating outputs sequentially where later elements condition on earlier ones. "Parallel decoding offers greater speed, while autoregressive decoding may provide higher-quality predictions and allow for separate checkpoints to be used for the policy versus the world model and value function."

- Best-of-N sampling: A planning strategy that samples multiple candidate actions and executes the one with the highest predicted value. "Cosmos Policy can use best-of-N sampling to plan by generating candidate actions, imagining their resulting future states, ranking these states by predicted value, and executing the highest-value action."

- Bimanual manipulation: Robot control tasks requiring coordinated use of two arms or manipulators. "challenging real-world bimanual manipulation tasks"

- Conditioning mask: A mask used during training to control which inputs are kept clean versus noised for conditional generation. "During training, a conditioning mask is used to ensure that the first latent frame corresponding to the input image remains clean (without noise) while subsequent frames are corrupted with noise."

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism that conditions one sequence on another (e.g., text conditioning video). " conditions on via cross-attention and on via adaptive layer normalization"

- Diffusion transformer: A transformer architecture used as the denoiser inside diffusion models. "and is a diffusion transformer"

- Discount factor: A scalar in reinforcement learning that exponentially downweights future rewards. "where is a discount factor that backpropagates the terminal reward through time."

- EDM denoising score matching: A diffusion training objective (Elucidated Diffusion Model) that learns the score function by denoising at controlled noise levels. "and is trained using the EDM denoising score matching formulation"

- Ensemble predictions: Aggregating multiple stochastic predictions to improve robustness or accuracy. "we ensemble the predictions by querying the world model three times per action and the value function five times per future state"

- Expected rewards-to-go: The expected cumulative future reward from a given state (or future state). "value (expected rewards-to-go at the future state)"

- Imitation learning: Training policies to mimic expert demonstrations rather than learning solely from reward signals. "We train policies via imitation learning on expert demonstrations"

- Implicit physics: Physical dynamics captured indirectly by a model without explicit physics simulation. "pretrained video generation models learn temporal causality, implicit physics, and motion patterns from millions of videos."

- Latent diffusion: Diffusion modeling performed in a compressed latent space rather than pixel space. "latent diffusion process"

- Latent frame injection: Encoding non-visual modalities (e.g., actions, proprioception, values) as additional latent frames inserted into the video model’s diffusion sequence. "We illustrate latent frame injection---the primary mechanism for adapting the pretrained Cosmos-Predict2 into a policy that can predict robot actions, future states, and values without architectural changes."

- Latent frames: Spatiotemporal latent tensors produced by a video tokenizer/encoder that represent frames in compressed space. "we interleave new modalities (robot state, action chunk, and state values) and images from additional camera views by inserting new latent frames between existing image latent frames."

- Majority mean: An aggregation rule that averages predictions within the majority class (e.g., success vs. failure) to reduce outlier influence. "We aggregate these via 'majority mean'"

- Markov decision process (MDP): A formalism for sequential decision-making defined by states, actions, transition dynamics, rewards, and horizon. "We frame robotic manipulation tasks as finite-horizon Markov decision processes (MDPs) defined by the tuple"

- Model-based planning: Planning that uses a learned or known dynamics model to predict outcomes of candidate actions. "we compare our model-based planning approach to a model-free variant"

- Model-free (planning): Planning or decision-making without explicitly modeling environment dynamics, often via learned value functions. "a model-free variant"

- Model-predictive control (MPC): A control strategy that optimizes actions over a receding horizon using a dynamics model. "from classical model-predictive control to modern neural approaches."

- Monte Carlo returns: Empirical returns computed from full-episode outcomes used as targets for value estimation. "We simply use Monte Carlo returns in this work"

- MPPI (Model Predictive Path Integral): A sampling-based stochastic MPC method for trajectory optimization. "uses separate world and reward models with MPPI planning to iteratively search for better actions and refine the base policy"

- Multimodal distributions: Distributions with multiple modes, reflecting several distinct likely outcomes or actions. "Since video models are effective at modeling complex, high-dimensional, multimodal distributions"

- Proprioception: Robot-internal sensing of its body configuration (e.g., joint angles, end-effector pose). "represented by robot proprioception"

- Receding-horizon control: Executing only the first part of an optimized action sequence before replanning at the next step. "as done in receding-horizon control"

- Rollout data: Trajectories collected by executing a policy in the environment, used for further training or evaluation. "We collect rollout data by deploying Cosmos Policy in diverse initial conditions and recording the trajectory as well as the episode outcome (success/fail or a fractional score)."

- Spatiotemporal priors: Prior knowledge learned from data about how scenes evolve in space and time. "These spatiotemporal priors hold significant value for robotics applications."

- Spatiotemporal VAE tokenizer: A variational autoencoder-based module that compresses videos into latent tokens across space and time. "the Wan2.1 spatiotemporal VAE tokenizer"

- State value function: A function that predicts expected return from a state under a policy (often denoted V). "world model and state value function"

- State-action value function (Q-function): A function that predicts expected return from taking an action in a state (denoted Q). "a Q-value function (a model-free variation)"

- T5-XXL embeddings: High-capacity text embeddings produced by the T5-XXL LLM for conditioning. "encoded as T5-XXL embeddings"

- Value function: A function estimating expected (discounted) returns used for evaluating or guiding policies. "The value function for a policy at state represents expected discounted returns from under ."

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): A probabilistic generative model used here to encode/decode video frames into/from latents. "where is a clean VAE-encoded image sequence"

- Video diffusion model: A diffusion generative model specialized for producing or predicting video sequences. "a latent video diffusion model that receives a starting image and textual description as input and predicts subsequent frames to create a short video."

- Visuomotor control: Robot control problems that map visual observations to motor commands. "enable visuomotor control and planning."

- World model: A learned dynamics model that predicts future states given current states and actions. "A world model learns to predict the future state given current state and action, approximating the true environment dynamics."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.