DeepSeek-V3.2: Pushing the Frontier of Open Large Language Models (2512.02556v1)

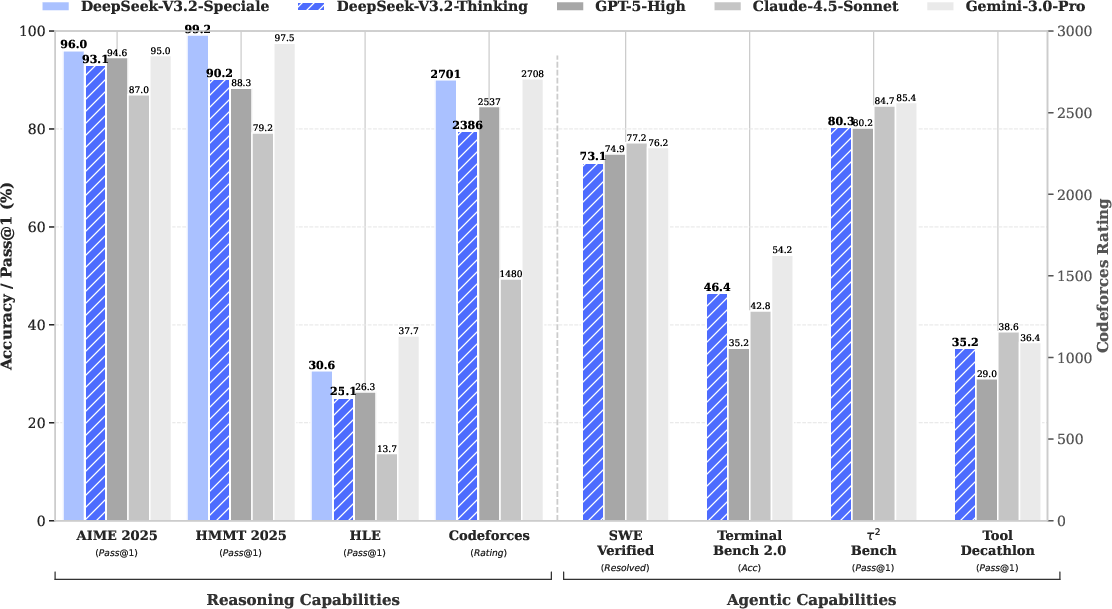

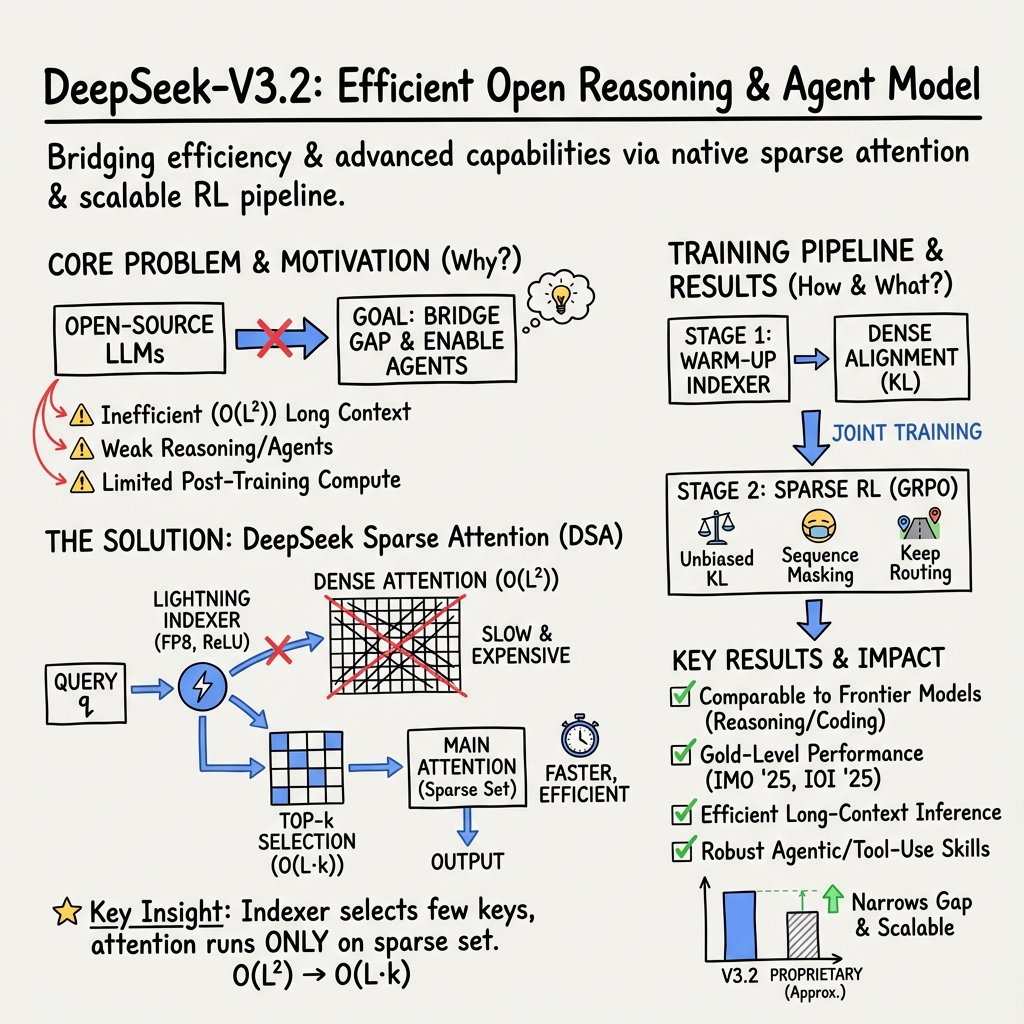

Abstract: We introduce DeepSeek-V3.2, a model that harmonizes high computational efficiency with superior reasoning and agent performance. The key technical breakthroughs of DeepSeek-V3.2 are as follows: (1) DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA): We introduce DSA, an efficient attention mechanism that substantially reduces computational complexity while preserving model performance in long-context scenarios. (2) Scalable Reinforcement Learning Framework: By implementing a robust reinforcement learning protocol and scaling post-training compute, DeepSeek-V3.2 performs comparably to GPT-5. Notably, our high-compute variant, DeepSeek-V3.2-Speciale, surpasses GPT-5 and exhibits reasoning proficiency on par with Gemini-3.0-Pro, achieving gold-medal performance in both the 2025 International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) and the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI). (3) Large-Scale Agentic Task Synthesis Pipeline: To integrate reasoning into tool-use scenarios, we developed a novel synthesis pipeline that systematically generates training data at scale. This methodology facilitates scalable agentic post-training, yielding substantial improvements in generalization and instruction-following robustness within complex, interactive environments.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces DeepSeek‑V3.2, a new open LLM. The big idea is to make the model both smart and efficient: it should think well on tough problems and also run faster and cheaper, especially when reading very long inputs. The authors also teach the model to act like an “agent” that can use tools (like web search or coding environments) and follow instructions reliably.

What were the researchers trying to do?

They focused on three simple goals:

- Make long reading cheaper and faster: Most LLMs slow down a lot when the input is very long. The team wanted to fix that without hurting accuracy.

- Improve “post‑training” with more compute: After pretraining on lots of text, models still need practice with feedback to get good at hard tasks. The team wanted to scale this step safely and effectively.

- Build better tool‑using agents: They wanted the model to think step‑by‑step while using tools (search, code, notebooks) and handle complex, interactive tasks more reliably.

How did they approach it?

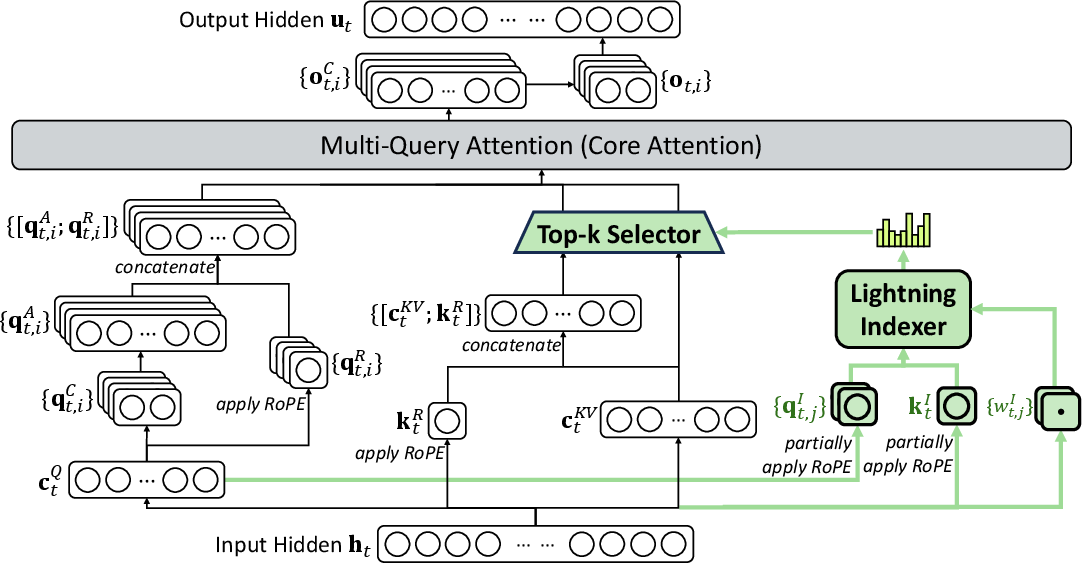

1) A faster way to pay attention: DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA)

- What “attention” means: When a model reads a long passage, it tries to decide which earlier words matter for each new word it generates. Standard attention compares every word to every other word—like rereading an entire textbook for each question. That’s slow and expensive.

- What DSA does: DSA adds a quick “lightning indexer” that scores which past pieces are likely to be useful, then only looks closely at the top few. Think of it like using a highlighter to mark the important parts before you read in detail.

- Why that helps: Instead of comparing “everything with everything,” it compares “each word with just the important bits,” which makes processing very long inputs much faster and cheaper—while keeping quality high.

They trained DSA in two steps:

- Warm‑up: Keep normal attention but teach the indexer what the model usually looks at.

- Sparse training: Switch to the new, faster pattern and fine‑tune everything so the model adapts to this efficient style.

2) Scaling post‑training with Reinforcement Learning (RL)

- What post‑training is: After pretraining on lots of text, the model practices with feedback to get better at reasoning, following instructions, and being helpful. This paper uses a method called GRPO (a group-based version of PPO) to learn from rewards.

- How they stabilized RL at scale: They added practical “safety rails” so training doesn’t become unstable when generating lots of model answers:

- Fairer KL penalty estimates: Better math for consistent updates.

- Masking bad off‑policy samples: Skip “unhelpful” mistakes that are too far from the current model’s behavior.

- Keep routing (for MoE models): Make sure the same “expert” parts of the model are used in training as in sampling.

- Keep sampling masks: Match how the model sampled words during data collection and training (so math assumptions stay true).

- More compute: They invested more compute into this stage—over 10% of the pretraining cost—because that’s where a lot of reasoning ability comes from.

3) Teaching with specialists and synthetic agent tasks

- Specialist distillation: They first fine‑tune “specialist models” for areas like math, coding, logic, agents, and search. Then they use the specialists to create training data and distill their skills into one main model. Finally, they use RL to polish everything together.

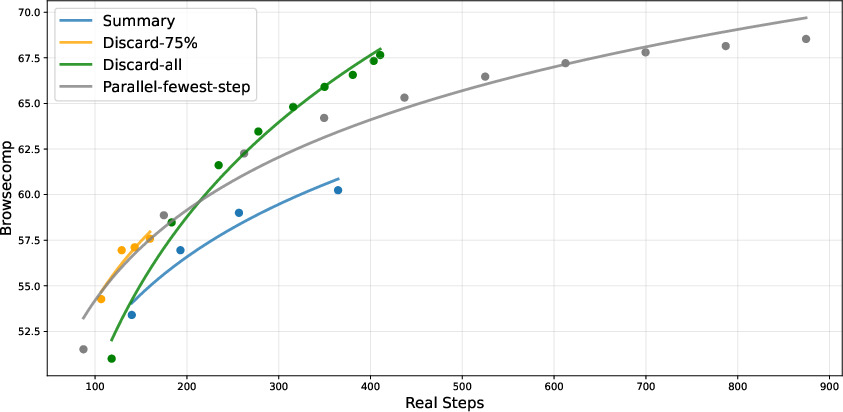

- Thinking while using tools: They designed a better “context manager” so the model keeps its prior reasoning intact across tool calls (like search results or code outputs). This avoids rethinking everything from scratch each step, saving tokens and time.

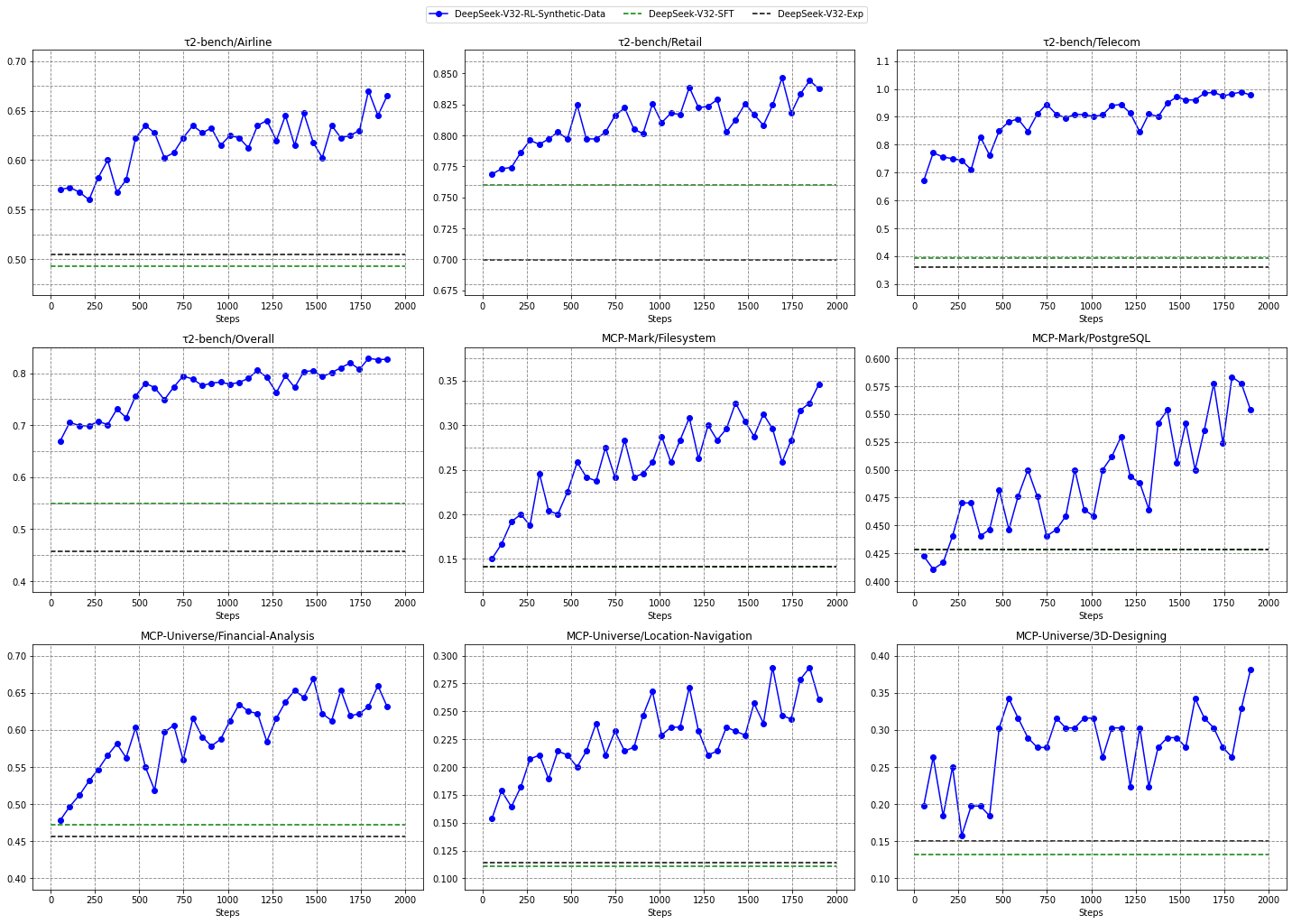

- Large‑scale agentic task synthesis: They built thousands of real and synthetic tool‑using tasks:

- Real tools: Web search APIs, code tools, Jupyter Notebook for computations.

- Code agent: Build and test real software environments from GitHub issues and patches, checking if fixes work without breaking other things.

- General agent: Automatically created 1,800+ mini‑environments (like trip planning with constraints) with tools and verifiers that can automatically check if a solution is correct.

- Reward models and rules: They used clear rubrics and automatic checks to reward correct, helpful, and concise behavior.

What did they find?

- Faster and cheaper for long inputs: With DSA, the cost of attention drops from “grows with the square of the length” to “grows roughly with length times a small number of chosen tokens.” In everyday terms, it gets much cheaper to handle long documents without losing accuracy.

- Similar or better performance: On many reasoning benchmarks (math, science questions, coding challenges), DeepSeek‑V3.2 performs on par with strong proprietary models in the authors’ tests, while using fewer tokens than some competitors.

- Better tool‑using agents: The model handles complex tool‑using tasks more reliably—like searching online, coding and fixing software bugs, and following multistep instructions in new environments it didn’t see during training.

- A high‑compute variant performs even better: An experimental version, DeepSeek‑V3.2‑Speciale, was trained to think longer on hard problems and, according to the authors, reaches or beats top systems on some reasoning and coding benchmarks.

- Strong generalization: Even on new agent tasks and tools that weren’t in training, the model applies its strategies well, which suggests real-world usefulness.

Why is this important?

- Practical long‑context use: Many real tasks involve long documents—legal texts, research papers, codebases, or long chats. DSA makes these practical by cutting cost without cutting quality.

- Reliable agents: The model doesn’t just chat—it can plan, search, code, verify, and adapt. That’s key for assistants that solve real problems.

- Open progress: The work narrows the gap between open models and top closed models. Faster, capable open models help research, education, and startups by making advanced AI more accessible.

- Safer, steadier training at scale: Their RL techniques show how to grow post‑training compute without causing unstable behavior, which is useful for the whole field.

Bottom line

DeepSeek‑V3.2 combines a smarter way to “pay attention” with large‑scale, carefully stabilized training and a big library of tool‑using tasks. The result is an open model that reads long inputs more efficiently, reasons better, and acts more like a helpful, reliable agent. If widely adopted, these ideas could make AI assistants faster, cheaper, and more capable in everyday, real‑world work.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased so that future researchers can act on it.

- DSA theoretical properties are not analyzed: no formal guarantees on approximation error vs. dense attention, stability bounds, or convergence impacts when the indexer drives token selection.

- The lightning indexer still has O(L2) complexity; the paper does not quantify when indexer overhead dominates for very long contexts, nor explore indexer sparsification or subquadratic alternatives.

- Choice of top-k=2048 is fixed and unmotivated; there are no ablations or adaptive schemes (per-token, per-layer, per-domain) to optimize k for quality/compute trade-offs.

- No sensitivity paper on DSA hyperparameters (number of indexer heads HI, projection dimension dI, activation function choice, FP8 quantization) and their effects on accuracy, latency, and memory.

- The warm-up stage aligns the indexer to dense attention via KL, but there is no comparison to other selection targets (e.g., learned retrieval objectives, gradient-based importance, locality priors) nor justification that dense attention is the best teacher.

- The indexer inputs are detached from the main model’s graph during sparse training; the impact of joint vs. separate optimization on learning dynamics and end-task performance is not evaluated.

- DSA is instantiated under MLA in MQA mode; portability to other attention architectures (e.g., standard MHA, multi-query variants, hybrid retrieval-augmented attention) and the trade-offs are not studied.

- Short-context “masked MHA mode to simulate DSA” is used for prefilling, but the approximation gap vs. true DSA and its effect on outputs/latency is not quantified.

- Memory footprint and KV cache behavior under DSA (e.g., fragmentation, cache-hit rates, sharing across queries) are not reported; practical memory bottlenecks are unknown.

- There is no failure-mode analysis of DSA (e.g., when critical long-range dependencies are pruned by the indexer) and no diagnostics to detect/mitigate selection errors at inference.

- Continued pre-training data is said to be “aligned with 128K long context extension data” but sources, composition, filtering, and contamination controls are unspecified; reproducibility and benchmark leakage remain unclear.

- Compute budgeting is only described qualitatively (“>10% of pre-training cost”); exact FLOPs, wall-clock, hardware mix, and scalability curves for RL vs. pretrain are missing.

- GRPO hyperparameters (group size G, ε, β, learning-rate schedules, update/rollout ratios) and their domain-specific tuning are not disclosed; robustness to these settings is untested.

- The “Unbiased KL estimate” is introduced without a formal proof or empirical validation of unbiasedness in practice (especially under truncation masks); the variance properties and stability trade-offs are not characterized.

- Off-Policy Sequence Masking uses a KL threshold δ, but δ is undefined and no sensitivity analysis shows how δ affects stability, performance, or sample efficiency across tasks.

- Keep Routing for MoE is proposed, yet there are no quantitative results showing how much it reduces instability or off-policyness, nor the overhead and compatibility with various inference stacks.

- Keep Sampling Mask with top-p/top-k addresses action-space mismatch, but there is no theoretical treatment on bias/variance in policy gradient estimates nor empirical ablations vs. alternative off-policy corrections.

- Reward models: design, training data, calibration, inter-rater reliability, and robustness to reward hacking are not described; no audits of generative rubrics or cross-domain validity are provided.

- Agentic task synthesis lacks public release of environments/tools/data or detailed recipes; reproducibility and licensing/legal constraints (e.g., mined GitHub PRs) are unresolved.

- The search-agent pipeline may introduce selection bias (retaining items where all candidate models fail); impacts on generalization and dataset difficulty calibration are not assessed.

- Code agent environments are “executable” but portability, determinism, and flakiness across platforms are not reported; failure rates and environment setup reproducibility metrics are missing.

- The general-agent synthesis (1,827 environments, 4,417 tasks) filters by pass@100>0; selection effects on difficulty and diversity, and how this impacts RL learning signals, are not studied.

- Thinking-context retention in tool use is heuristic; it increases token efficiency but potential risks (e.g., sensitive info persistence, context poisoning, prompt-injection resilience) and compatibility across frameworks are not analyzed.

- The paper notes self-verification causes long trajectories exceeding 128K, hurting performance; there is no mechanism or paper to control redundant self-checking (e.g., calibrated stopping, verifier-cost regularization).

- Speciale variant “relaxes length constraints” but the exact changes (context window, length penalty settings, reward models) and their impact on cost/quality are not documented.

- Benchmarks sometimes use internal environments (e.g., MCP) and context management tricks; comparability to official setups and the magnitude of environment-induced variance are not quantified.

- No comprehensive ablations isolating contributions of DSA, specialist distillation, RL scaling strategies, and agentic synthesis; it’s unclear which component drives which gains.

- Temperature=1.0 and template choices vary across tasks; sensitivity of results to decoding parameters, templates, and tooling formats (e.g., function-call roles) is not reported.

- Multilingual capability is claimed in parts (e.g., BrowseCompZh, code across languages) but broader multilingual reasoning/agentic performance and training data composition across languages remain uncharacterized.

- Safety, alignment, and misuse evaluations (jailbreak resistance, harmful content, tool-use safety, data privacy, provenance) are absent; alignment training details and metrics are insufficient.

- Carbon/energy footprint and cost-at-scale for DSA and high-compute RL are not provided; practical deployment trade-offs on non-H800 hardware are unknown.

- The provided open-source artifacts appear limited to inference; training code, reward models, environments, and data are not released, impeding independent verification.

- Figures reference LCP metrics and visualizations, but the paper does not define LCP nor explain how it is computed and used; interpretability of these plots is unclear.

- Several headline claims (e.g., “gold-medal” performance on IMO/IOI/ICPC) are not substantiated with protocols, official standings, or reproducible evaluations.

Glossary

- Advantage (RL): The baseline-adjusted reward signal used to scale policy gradients for each action or token. "The advantage of is calculated by subtracting the average reward of the group from the reward of output , i.e., ."

- Agentic: Pertaining to tool-using, interactive behaviors of LLMs acting as agents in environments. "Subsequently, we advance to large-scale agentic task synthesis, where we generate over 1,800 distinct environments and 85,000 complex prompts."

- Attention complexity: The computational cost of attention with respect to sequence length, often for dense attention. "DSA reduces the core attention complexity of the main model from $\order{L^2}$ to $\order{L k}$, where () is the number of selected tokens."

- Catastrophic forgetting: The degradation of previously learned abilities when training sequentially on new tasks. "This approach effectively balances performance across diverse domains while circumventing the catastrophic forgetting issues commonly associated with multi-stage training paradigms."

- Continued pre-training: Further large-scale unsupervised training starting from an existing checkpoint before post-training. "Starting from a base checkpoint of DeepSeek-V3.1-Terminus, whose context length has been extended to 128K, we perform continued pre-training followed by post-training to create DeepSeek-V3.2."

- DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA): A sparse attention mechanism using an indexer to select top-k key-value entries per query for efficiency. "We introduce DSA, an efficient attention mechanism that substantially reduces computational complexity while preserving model performance in long-context scenarios."

- FP8: An 8-bit floating-point numerical format used to accelerate and compress computations. "Given that the lightning indexer has a small number of heads and can be implemented in FP8, its computational efficiency is remarkable."

- Generative reward model: A learned evaluator that produces rubric-based scores for model outputs, used as rewards in RL. "For general tasks, we employ a generative reward model where each prompt has its own rubrics for evaluation."

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): An RL algorithm variant that normalizes rewards within groups to stabilize policy optimization. "For DeepSeek-V3.2, we still adopt Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)~\citep{deepseekmath,deepseekr1} as the RL training algorithm."

- Importance sampling ratio: The likelihood ratio between current and behavior policies used to correct off-policy bias. "is the importance sampling ratio between the current and old policy."

- K3 estimator: A specific approximation of KL divergence used in policy regularization that can be biased without correction. "we correct the K3 estimator \citep{schulman2020klapprox} to obtain an unbiased KL estimate"

- Keep Routing: A stability technique for MoE RL where the expert routes used during sampling are enforced during training. "This Keep Routing operation was found crucial for RL training stability of MoE models, and has been adopted in our RL training pipeline since DeepSeek-V3-0324."

- Keep Sampling Mask: A technique that reuses top-k/top-p truncation masks from sampling during training to align action spaces. "Empirically, we find that combining top-p sampling with the Keep Sampling Mask strategy effectively preserves language consistency during RL training."

- KL divergence: A measure of divergence between two probability distributions, used for regularization and loss design. "we set a KL-divergence loss as the training objective of the indexer:"

- Latent vector: The shared key-value representation (latent) used by MLA across query heads. "where each latent vector (the key-value entry of MLA) will be shared across all query heads of the query token."

- Lightning indexer: A lightweight module that scores tokens to select a sparse set of key-values for attention. "The lightning indexer computes the index score between the query token and a preceding token , determining which tokens to be selected by the query token:"

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): An architecture that routes inputs to a subset of expert subnetworks to increase capacity efficiently. "Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models improve computational efficiency by activating only a subset of expert modules during inference."

- MLA: An attention architecture (from DeepSeek-V2) using shared latent key-value entries for efficiency. "For the consideration of continued training from DeepSeek-V3.1-Terminus, we instantiate DSA based on MLA~\citep{deepseekV2} for DeepSeek-V3.2."

- MHA (Multi-Head Attention): The standard attention variant with multiple heads; used here in a masked mode for efficiency. "Note that for short-sequence prefilling, we specially implement a masked MHA mode to simulate DSA, which can achieve higher efficiency under short-context conditions."

- MQA (Multi-Query Attention): An attention variant where multiple query heads share a single key-value set. "Therefore, we implement DSA based on the MQA~\citep{MQA} mode of MLA"

- Off-Policy Sequence Masking: A stability method that masks highly off-policy negative samples during RL updates. "We empirically observe that this Off-Policy Sequence Masking operation improves stability in certain training scenarios that would otherwise exhibit instability."

- Pass@100: A success metric measuring whether any of 100 attempts solves a task. "retain only instances with non-zero pass@100, resulting in 1,827 environments and their corresponding tasks (4,417 in total)."

- ReLU: A common activation function defined as max(0, x), chosen for throughput efficiency here. "We choose ReLU as the activation function for throughput consideration."

- Sparse attention: Attention that restricts each query to a subset of tokens to reduce compute. "The post-training of DeepSeek-V3.2 also employs sparse attention in the same way as the sparse continued pre-training stage."

- Tool-use: The integration of external tools (e.g., search, code execution) into LLM reasoning and interaction. "To integrate reasoning into tool-use scenarios, we developed a novel synthesis pipeline that systematically generates training data at scale."

- Top-k sampling: A decoding strategy that samples from the k most probable tokens at each step. "Top-p and top-k sampling are widely used sampling strategies to enhance the quality of responses generated by LLMs."

- Top-p sampling: A nucleus sampling strategy that samples from the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds p. "Top-p and top-k sampling are widely used sampling strategies to enhance the quality of responses generated by LLMs."

- Unbiased KL estimate: A corrected KL-divergence estimator whose gradient is unbiased under importance sampling. "we correct the K3 estimator \citep{schulman2020klapprox} to obtain an unbiased KL estimate"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by leveraging DeepSeek‑V3.2’s sparse attention (DSA), post‑training recipes, agentic task synthesis, and thinking-in-tool‑use techniques.

- Cost‑efficient long‑context inference

- Sectors: software, legal/compliance, finance, healthcare, education

- What it does: Uses DSA to reduce attention complexity from O(L2) to O(L·k), enabling faster, cheaper inference on long documents (up to 128K tokens) without performance loss.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “LongDoc Copilot” for contract review and e‑discovery; financial report summarizer for earnings calls and prospectuses; literature review copilot for academia; EHR guideline summarization assistants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: FP8 indexer support and optimized kernels; reliance on H800‑class GPU clusters or equivalent; 128K context window constraint; correct top‑k token selection and MLA/MQA implementation.

- Verifiable enterprise search assistant

- Sectors: enterprise search, knowledge management, customer support

- What it does: Builds a multi‑agent search pipeline with verification and rubrics to provide factual, self‑checked answers (as shown in the Search Agent pipeline).

- Example tools/products/workflows: “Verifiable Search Copilot” for intranet/Internet QA; research desk assistant that cross‑checks sources; helpdesk assistant that explains why competing answers are incorrect.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to commercial search APIs; reward models and rubrics for scoring; 128K context window may require context management for long sessions; data governance for source logging.

- Agentic code troubleshooting and auto‑patching

- Sectors: software engineering, DevOps, CI/CD

- What it does: Uses the Code Agent pipeline to spin up reproducible environments from issue–PR pairs, execute tests, and propose fixes validated by JUnit‑style outputs.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “Auto‑PR Fixer” integrated into CI pipelines; nightly repair bot that opens validated PRs for flaky tests and narrow regressions; staging environment builders for multi‑language repos.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable sandboxing, dependency resolution, and test runners; coverage across major languages; security policies for executing untrusted code; human‑in‑the‑loop governance for merge decisions.

- Thinking retention for tool‑calling conversations

- Sectors: agent frameworks, customer support, RPA

- What it does: Applies the paper’s context management: retain reasoning across tool outputs, discard only on new user messages, and preserve tool‑call history—reducing token waste and improving multi‑step tool workflows.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “Context Manager middleware” for function‑calling agents; upgrades to agent SDKs to emit tool‑role messages instead of user‑role in tool interactions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Framework compatibility (Roo Code/Terminus may require non‑thinking mode or adaptation); consistent use of tool roles; session management to avoid exceeding 128K tokens.

- Stable RL training for LLMs (GRPO recipes)

- Sectors: machine learning engineering, model training platforms

- What it does: Improves RL stability via Unbiased KL estimate, Off‑Policy Sequence Masking, Keep Routing for MoE, and Keep Sampling Mask—reducing training‑inference mismatch and off‑policy drift.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “GRPO‑Suite” training library; RLHF/RLAIF pipelines with MoE routing persistence; reproducible RL training playbooks for multi‑domain specialists.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ability to log sampling masks and expert routing paths at inference; consistent training/inference stacks; domain‑specific reward models; compute budgets ≥10% of pretraining (as suggested by the paper’s scaling).

- Synthetic but verifiable agent environments for internal training

- Sectors: enterprise AI enablement, education/assessment, simulations

- What it does: Uses the General Agent synthesis workflow to create thousands of auto‑verifiable tasks (e.g., trip planning) with tool interfaces and verifiers—ideal for robust agent training and evaluation.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “AgentGym” with prebuilt environments and verifiers; courseware that grades tool‑mediated solutions automatically; internal sandboxes to stress‑test agent generalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality of verifiers and toolsets; secure sandboxing; alignment of synthesized tasks with real‑world roles; compute for RL and evaluation.

- Data‑driven math and reasoning tutoring

- Sectors: education, test prep

- What it does: Deploys DeepSeek‑V3.2’s strong math/reasoning modes for step‑by‑step problem solving using boxed answers and chain‑of‑thought where permitted.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “Math Coach” for AIME/HMMT/IMO prep; classroom assistants that verify steps and encourage self‑checking via rubrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Local policies on chain‑of‑thought exposure; domain‑specific reward models to avoid verbosity; guardrails to prevent overfitting to benchmarks.

- Cost planning and capacity management for LLM ops

- Sectors: AI operations, finance/IT procurement

- What it does: Uses reported token‑position cost curves and DSA speedups to forecast GPU hours and optimize batch sizes for long‑context workloads.

- Example tools/products/workflows: “LLM Cost Planner” dashboards; autoscaling policies tuned to sparse attention profiles; procurement models using $/GPU‑hour benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Transferability of H800 cost curves to target hardware; accurate telemetry; workload‑specific k/top‑k settings.

- Open‑model adoption in public sector and regulated industries

- Sectors: public administration, compliance, healthcare (non‑diagnostic), finance

- What it does: Offers a cost‑efficient open alternative that narrows the gap to frontier models in reasoning and tool‑use—suitable for document workflows and auditable processes.

- Example tools/products/workflows: Records summarization with traceable tool‑calls; compliance audits with verifiable evidence chains; transparent agent logs for oversight.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy and security hardening; domain fine‑tuning; policy approvals; audit trails that capture tool outputs and reasoning retention.

Long‑Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, or productization—particularly extending context windows, generalization, reward modeling, or safety.

- Million‑token context assistants for “workspace memory”

- Sectors: legal, finance, biomedical research, enterprise knowledge

- What it could do: Combine DSA with retrieval and future indexer scaling to reason over multi‑million‑token corpora (contracts, codebases, lab notebooks) in a single session.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Workspace Memory OS” that maintains persistent, sparse‑indexed key‑value memories; continuous compliance monitors reading entire policy libraries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware/kernel support for extreme contexts; indexer accuracy at scale; memory management and safety for very long traces.

- Autonomous multi‑tool orchestration for complex operations

- Sectors: IT operations, MLOps, supply chain, RPA

- What it could do: Use the paper’s agentic synthesis + stable RL training to orchestrate planning, search, code changes, and verification across heterogeneous tools.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Agentic Orchestrator” that plans workflows, deploys fixes, and self‑verifies outcomes; production “pass@N” gates with verifier functions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust generalization to unseen environments; strong verifiers and fail‑safes; human oversight; compliance logging.

- Autonomous software maintainer at scale

- Sectors: software platforms, open‑source ecosystems

- What it could do: Continuously mine issues, generate candidate patches, validate via tests, and propose PRs with summarized rationale and risk.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Autonomous Maintainer” integrated into large repos; triage bots prioritizing high‑impact fixes; release‑readiness verifiers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Repository trust models; secure execution; social governance (maintainers retain control); cross‑language test reliability.

- Self‑verifying research copilot

- Sectors: academia, industrial R&D, data science

- What it could do: Leverage code interpreter agents to reproduce analyses, run sensitivity checks, and validate claims via multi‑pass verification.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Lab Notebook Copilot” in Jupyter; reproducibility badges auto‑generated via verifiers; assistants that correct flawed analyses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to datasets and tooling; robust reward/rubric models; provenance tracking; policies for code execution in research settings.

- Regulatory compliance auditors with verifiable tool traces

- Sectors: finance, healthcare, telecom, retail (e.g., tau2 domains)

- What it could do: Standardize tool‑use audits with context retention and verification—producing machine‑checkable evidence chains for decisions.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Compliance Auditor” that maps decisions to tools, thresholds, and verifiers; certification workflows based on MCP/tau2‑like benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain‑specific verifiers; policy alignment; secure connectors into regulated systems; long‑context stability and logging.

- Standardized agent certification and benchmarking

- Sectors: AI assurance, procurement, education

- What it could do: Extend MCP‑Universe/Mark and tau2 into certification tracks measuring generalization, verifiability, and efficiency under sparse attention.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Agent Certification Suite” with graded difficulty, tool‑use constraints, and self‑verification metrics; procurement scorecards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; unbiased, domain‑relevant tasks; standardized environments and tool APIs.

- Energy‑efficient edge reasoning

- Sectors: robotics, embedded systems, IoT

- What it could do: Adapt DSA and MLA/MQA kernels for edge accelerators to enable sparse long‑context reasoning on constrained hardware.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Edge Reasoner” that performs local planning with limited compute; hybrid on‑device/off‑cloud tool‑use.

- Assumptions/dependencies: FP8 and sparse kernels on edge hardware; memory bandwidth; safety for autonomous operations.

- Safer, rubric‑guided alignment with generative reward models

- Sectors: platform safety, content moderation, education

- What it could do: Expand rubric‑based generative reward models to multi‑domain alignment, discouraging unhelpful verbosity and enforcing language consistency.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Rubric Alignment Studio” to author domain rubrics; audit dashboards for reward‑driven policies; classroom assistants that grade reasoning quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High‑quality rubric design; calibration to avoid mode collapse; transparent evaluation; continuous monitoring for unintended bias.

- Persistent “thinking” memory across multi‑session tool workflows

- Sectors: enterprise productivity, customer service

- What it could do: Generalize the paper’s context retention mechanism beyond single sessions—maintaining verified reasoning traces across sessions and teams.

- Potential tools/products/workflows: “Reasoning Memory Layer” attached to CRMs/project tools; cross‑agent handoffs with retained thinking and verifiers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Storage and retrieval policies; privacy controls; deduplication and summarization of long traces; governance on what thinking is stored.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.