Fara-7B: An Efficient Agentic Model for Computer Use

Abstract: Progress in computer use agents (CUAs) has been constrained by the absence of large and high-quality datasets that capture how humans interact with a computer. While LLMs have thrived on abundant textual data, no comparable corpus exists for CUA trajectories. To address these gaps, we introduce FaraGen, a novel synthetic data generation system for multi-step web tasks. FaraGen can propose diverse tasks from frequently used websites, generate multiple solution attempts, and filter successful trajectories using multiple verifiers. It achieves high throughput, yield, and diversity for multi-step web tasks, producing verified trajectories at approximately $1 each. We use this data to train Fara-7B, a native CUA model that perceives the computer using only screenshots, executes actions via predicted coordinates, and is small enough to run on-device. We find that Fara-7B outperforms other CUA models of comparable size on benchmarks like WebVoyager, Online-Mind2Web, and WebTailBench -- our novel benchmark that better captures under-represented web tasks in pre-existing benchmarks. Furthermore, Fara-7B is competitive with much larger frontier models, illustrating key benefits of scalable data generation systems in advancing small efficient agentic models. We are making Fara-7B open-weight on Microsoft Foundry and HuggingFace, and we are releasing WebTailBench.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper introduces two main things:

- FaraGen: a system that automatically creates lots of realistic “how to use a website” examples without needing humans to record them.

- Fara‑7B: a small AI model trained on those examples to act like a helpful computer assistant. It “sees” the computer screen as an image, thinks about what to do, and then clicks, types, or scrolls to complete tasks.

The big idea is to make computer use agents (CUAs)—AIs that can operate your computer—work well even when the model is small and fast enough to run on your own device, instead of relying on huge, expensive cloud models.

Goals: What questions were they trying to answer?

The researchers focused on simple, practical goals:

- How can we create a large, high-quality “training set” of computer interactions, without hiring lots of people to record them?

- Can a small model learn to use websites just by looking at screenshots and predicting what to do next?

- Will this small model perform well on common web tasks like shopping, booking restaurants, looking up info, and planning activities?

- Can this approach be cheaper, faster, and more private than using giant cloud models?

Approach: How did they do it?

To keep this easy to understand, think of the system as a team that plans tasks, tries them, and checks if they worked—like a teacher making assignments, a student doing them, and graders verifying the work.

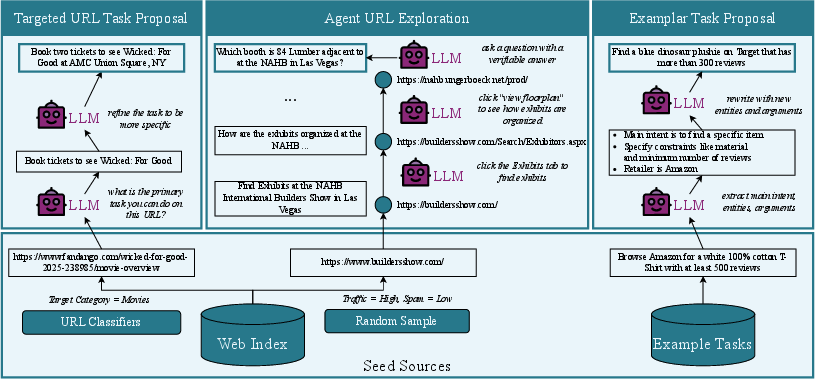

1) Creating tasks (Task Proposal)

They needed realistic tasks people actually do online. They used three strategies:

- Targeted URLs: Start with specific websites (like movie ticket pages or restaurant sites) and turn them into clear, step-by-step tasks you can verify.

- Agentic exploration: Pick random websites, let an AI explore them, and build tasks based on what’s possible there.

- Template expansion: Take a common task (like “buy this item”) and automatically create variations (different items, stores, or constraints).

This gave them lots of diverse tasks—simple ones (find information) and complex ones (compare prices, book tickets, create shopping lists).

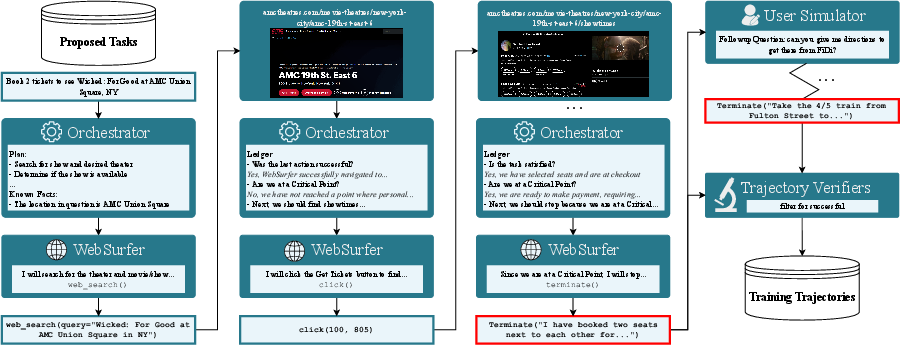

2) Solving tasks (Task Solving)

They used a two‑agent system, like a coach and a driver:

- Orchestrator (the coach): Plans the steps, watches progress, and prevents mistakes.

- WebSurfer (the driver): Actually interacts with the browser—clicks, types, scrolls—based on screenshots and page structure.

They also defined “critical points”—moments when the AI should stop and ask permission before doing something serious, like paying, logging in, or sending personal info. If they reach a critical point, the AI pauses. A “User Simulator” can then provide information or approvals in a controlled way to continue safely.

To scale this up, they ran many sessions in parallel and improved reliability with techniques like session management and retrying on errors.

3) Checking results (Trajectory Verification)

Even after solving tasks, they double-check correctness using three types of AI “verifiers”:

- Alignment verifier: Does the final result match the original task?

- Rubric verifier: Scores partial steps against a checklist of what “success” should look like.

- Multimodal verifier: Looks at key screenshots plus the final answer to make sure there’s evidence (helps catch hallucinations or made‑up facts).

Only verified, successful attempts go into the training set.

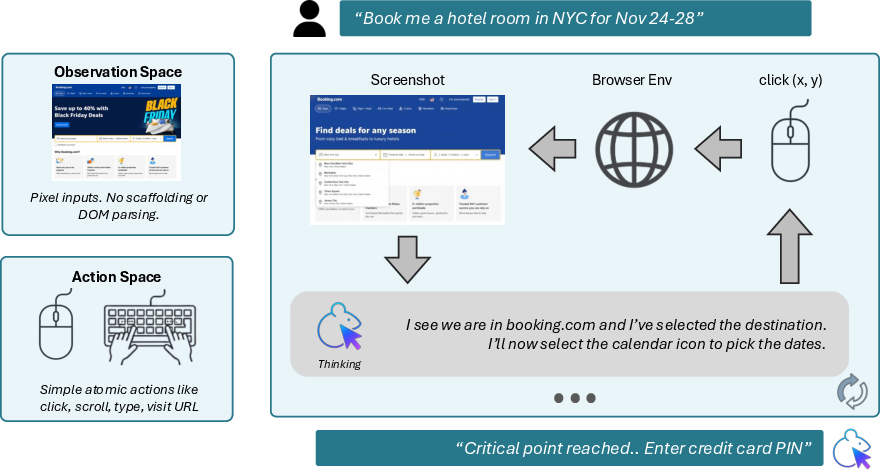

4) Building the model (Fara‑7B)

Fara‑7B is trained to operate like a human using a computer:

- It “sees” the screen as an image (a screenshot).

- It thinks in short steps (notes about what’s on the page and what to do next).

- It acts with simple tools: click, type, scroll, visit a URL, go back, search the web, memorize info for later, or terminate.

- For actions like clicking, it predicts the exact coordinates on the screen—like tapping a point on a phone.

Important detail: Although the data collection used extra page structure to help the agents, the final Fara‑7B model doesn’t need that at runtime. It works from pixels plus simple browser info, which makes it more robust across different websites.

Main Findings: What did they discover?

Here are the key results:

- Large, varied training data at low cost: They generated 145,000 verified “how to use a website” trajectories across 70,000 unique sites for about $1 per successful task.

- Strong performance with a small model: Fara‑7B outperformed other similar‑size computer-use models on benchmarks like WebVoyager and Online‑Mind2Web, and did well even against much larger models.

- Efficiency and speed: Compared to a similar 7B model (UI‑TARS‑1.5‑7B), Fara‑7B completed tasks in roughly half the steps, saving time and token cost.

- Pixel‑only works: Even without depending on website code structures during use, Fara‑7B could accurately click the right places and perform actions based on screenshots.

- Safety by design: The model is trained to stop at critical points (like before buying) and hand control back to the user.

- New benchmark: They released WebTailBench—609 tasks covering 11 under‑represented real‑world web scenarios—to better test generalization.

Why this matters: It shows that good synthetic data and careful verification can give small models real “agency”—the ability to do multi‑step tasks—without needing massive budgets or servers.

Implications: Why is this important and what could happen next?

This work points to practical benefits:

- Better personal assistants: A small, smart agent that can navigate websites could help with everyday tasks—shopping, booking, planning—using natural language.

- Privacy and speed: Because Fara‑7B is small, it can run locally on your device, keeping data private and reducing delays.

- Lower costs: Generating data was cheap, and using the model costs just a few cents per task—much less than giant models.

- Strong generalization: Training on diverse, verified tasks makes the model more reliable across different websites and layouts.

- Open ecosystem: They’re releasing the model weights and a new benchmark, which should accelerate progress and allow others to build on this.

In short, the paper shows how to train a capable, efficient computer‑use agent using synthetic data, smart verification, and a “pixel‑in, action‑out” design—making helpful computer assistants more accessible, affordable, and private.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, formulated to be actionable for future research.

- Training beyond “critical points” is intentionally excluded; the model’s behavior past checkout, authentication, payment, or irreversible actions is untested. How to safely and effectively learn post–critical-point behaviors (e.g., payment flows, 2FA, account creation, cancellations) remains open.

- The UserSimulator is used for only a small fraction of trajectories; the impact of richer multi-turn, follow-up interactions on performance is not quantified. Methods to scale and validate realistic user-in-the-loop extensions are needed.

- Data generation relies heavily on proprietary frontier models (o3, GPT-5) for Task Solving and verification; reproducibility with open-source models and the trade-offs in success rate, cost, and quality are not studied.

- Verifier reliability is limited (83.3% agreement, 16.7% FP, 18.4% FN); the effect of noisy verification labels on downstream training quality, especially for long-horizon tasks, is unmeasured. Learning or calibrating verifiers and estimating label noise impacts are open directions.

- Domain/task leakage risks are not addressed: WebTailBench is derived from the same proposal strategies, and there is no explicit de-duplication audit between training trajectories and benchmark tasks/domains. Clear leakage checks and reporting are needed.

- WebTailBench (609 tasks) is small and narrow in scope; coverage, difficulty calibration, and representativeness versus real-world usage remain unclear. Building larger, more diverse, and independently curated benchmarks is an open need.

- Synthetic tasks from random URL exploration are admitted to be simpler on average; principled generation of complex, compositional tasks (with dependencies, multi-website plans, and constraints) is underdeveloped.

- Training-time SoM/ax-tree scaffolding is used to derive coordinates, but inference is screenshot-only. The resulting domain shift and label noise from mapping element bounding boxes to click coordinates (e.g., non-clickable centers, dynamic hitboxes) is not quantified.

- The coordinate-only action grounding may be brittle under viewport changes, zoom/DPI scaling, responsive layouts, overlays, and occlusions. Robustness to varied device configurations, multi-monitor setups, and accessibility zoom is unexamined.

- Memory constraints (keeping only the most recent N=3 screenshots) for long-horizon tasks are set without ablation; the trade-offs between context window size, summarization, external memory, or retrieval mechanisms are not explored.

- Action space omissions (e.g., file upload, drag-and-drop, right-click/context menus, tab management, download handling, clipboard operations beyond basic key presses, modal/overlay dismissal, captcha handling) limit task coverage. Extending and evaluating richer action sets is open.

- Handling authentication, paywalls, cookie/GDPR banners, captchas, and rate limits is largely avoided; practical deployment requires systematic strategies for these ubiquitous web barriers.

- Safety is only partially addressed via critical points; broader risk management (e.g., phishing, misclicks on sensitive UI, malicious content, unintended purchases, data exfiltration) and formal safety evaluations are missing.

- Generalization to multilingual websites, non-English content, right-to-left scripts, locale-specific formats (dates, currencies), and non-U.S. web ecosystems is not evaluated.

- Non-web environments (desktop apps, mobile apps, native dialogs) are out of scope; the approach’s extensibility beyond browsers is untested.

- Latency, throughput, and resource usage for on-device inference are not reported (e.g., memory footprint, power draw, frame rate, end-to-end task completion time), despite claims of on-device advantages.

- The cost analysis for data generation is based on token pricing and small samples; variance across domains, task types, and model mixes, and end-to-end scalability to millions of trajectories remain unclear.

- The Multi-agent solving improvements table isolates WebSurfer changes, but training ablations (e.g., trajectory count, targeted vs. exploratory data mix, thoughts usage, memorize action utility, memory window size) are missing.

- Evaluation methodology relies on benchmarks and LLM judges; human-ground-truth evaluations at scale, especially for transactional tasks with objective outcomes, are limited.

- Robustness to dynamic content, A/B tests, personalization, geofencing, time-sensitive pages, and site redesigns is not thoroughly evaluated; strategies for adaptation and continual learning are open.

- The claimed grounding performance (“see Table \ref{tab:grounding}”) is referenced but not presented; quantitative grounding accuracy and error taxonomy (missed targets, off-by-pixels, overlay clicks) are needed.

- Privacy implications of storing and training on screenshots (potential incidental PII capture) and dataset release plans are not discussed; standardized redaction, consent, and compliance processes are an open requirement.

- Compliance with website terms of service and ethical use of automated browsing during data generation is not addressed; guidelines for responsible data collection and agent deployment on the open web are needed.

- Loop detection was engineered in the Orchestrator, but the standalone Fara-7B lacks explicit loop-avoidance diagnostics; its robustness to repetitive failure modes without external orchestration is unstudied.

- The Memorize action’s effectiveness is asserted but not quantified; measuring its contribution to cross-page information retention and downstream task success would clarify its value.

- Comparative evaluations against a broader set of open small-scale CUAs and larger multimodal agents, under equalized action spaces and constraints, are limited; standardized head-to-head comparisons are needed.

- The pipeline’s sensitivity to browser automation frameworks (e.g., Playwright vs. Selenium), rendering differences, and sandboxing environments (e.g., Browserbase) is only partially explored; portability remains an open question.

Practical Applications

Practical Applications Derived from the Paper’s Findings and Innovations

Below are actionable use cases that build directly on Fara-7B (a small, on-device computer-use agent), FaraGen (a scalable synthetic data engine for web tasks), and WebTailBench (a benchmark of underrepresented real-world web tasks). Each item notes relevant sectors, potential tools/products/workflows, and assumptions/dependencies.

Immediate Applications

- On-device browser assistant for repetitive web tasks

- Sector(s): software, productivity, enterprise IT

- Tools/Products/Workflows: a privacy-preserving desktop/browser extension powered by Fara-7B to handle multi-step tasks like form filling, price checks, itinerary planning, and reservations; runs locally to reduce latency and token cost

- Assumptions/Dependencies: screenshot-only perception; consistent screen resolution; tasks that do not require login or sensitive actions beyond “critical points”

- Safe-by-design agent guardrails via “critical point” enforcement

- Sector(s): policy/compliance, security, enterprise IT

- Tools/Products/Workflows: SDKs/middleware that implement the paper’s “critical point” logic (agent stops at irreversible or sensitive steps, asks for explicit approval or data)

- Assumptions/Dependencies: reliable detection of sensitive states; integration with consent prompts; human-in-the-loop workflows

- Cost-effective training and evaluation of CUAs with synthetic data

- Sector(s): academia, AI research, software

- Tools/Products/Workflows: FaraGen-powered dataset creation at ~$1/trajectory; WebTailBench adoption for underrepresented tasks; data services to bootstrap small agentic models

- Assumptions/Dependencies: access to web crawling infrastructure (e.g., Playwright); availability of verifiers; continued feasibility of generating data on live sites

- Automated website QA and regression testing using agent trajectories

- Sector(s): software quality, DevOps

- Tools/Products/Workflows: agent-driven test harnesses that navigate websites and validate flows using alignment, rubric, and multimodal verifiers; synthetic task proposals from seed URLs and exemplar expansion

- Assumptions/Dependencies: headless browsing (Playwright) stability; verifiers tuned to site-specific success criteria; handling of dynamic content

- Robust RPA augmentation with pixel-in, coordinate-out actions

- Sector(s): enterprise automation, operations

- Tools/Products/Workflows: replacing or complementing fragile DOM-based scripts with Fara-7B’s screenshot-grounded clicks/typing; workflows that generalize across heterogeneous web UIs

- Assumptions/Dependencies: consistent UI rendering; careful handling of scrolling and viewport changes; low-latency on-device inference

- Accessibility and assistive web operation via natural language

- Sector(s): accessibility, consumer tech, public sector

- Tools/Products/Workflows: voice-driven assistance to perform web tasks; local execution to preserve sensitive browsing data; “Memorize” tool for persistent cross-page information

- Assumptions/Dependencies: robust speech interfaces; safe interruption at critical points; support for diverse accessibility needs and screen configurations

- Back-office/customer support co-pilot for portal navigation

- Sector(s): customer support, contact centers, enterprise IT

- Tools/Products/Workflows: agents that traverse internal web portals and knowledge bases to retrieve status, update records, and prepare responses; human-in-the-loop on critical actions

- Assumptions/Dependencies: limited or no login flows in early deployments; secure environments; audit trails

- Information retrieval with evidence-checked outputs

- Sector(s): education, journalism, research

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “evidence mode” agents that collect screenshots and use a multimodal verifier to ensure answers are supported; improved hallucination resistance

- Assumptions/Dependencies: high-quality screenshot capture; verifier thresholds tuned for task types; reproducible browsing state

- Personal shopping, price comparison, and list-building

- Sector(s): e-commerce, consumer tech

- Tools/Products/Workflows: assistants that locate products, compare across retailers, and assemble shopping lists; safe handoffs before checkout

- Assumptions/Dependencies: no login/payment required for pre-checkout behavior; agents updated for retailer site changes

- Developer tool for “record-and-automate” workflow generation

- Sector(s): software engineering, productivity

- Tools/Products/Workflows: capture a user’s trajectory and auto-expand into related tasks via exemplar proposal; generate synthetic variants for testing or automation recipes

- Assumptions/Dependencies: reliable trajectory logging; exemplar expansion quality; versioning of tasks and verifications

- Benchmarking and model evaluation using WebTailBench

- Sector(s): academia, AI research

- Tools/Products/Workflows: standardized measurement across underrepresented tasks (e.g., multi-step shopping, travel, activities, reservations)

- Assumptions/Dependencies: shared benchmark adoption; reproducible site states; clear success criteria for verifiers

- Cloud cost reduction by substituting small, on-device agents

- Sector(s): enterprise IT, finance (cost control)

- Tools/Products/Workflows: replace frontier-model-based CUAs with Fara-7B for routine automation; manage token consumption and latency locally

- Assumptions/Dependencies: performance parity for targeted tasks; device compute availability; model updates for site drift

Long-Term Applications

- End-to-end transactional CUAs with secure identity handling

- Sector(s): e-commerce, travel, finance

- Tools/Products/Workflows: agents that progress beyond critical points to complete purchases/reservations; integration with password managers, wallets, and 2FA; auditable consent flows

- Assumptions/Dependencies: robust identity management; regulatory compliance (PCI, GDPR); advanced safety verification to prevent costly errors

- Cross-application, OS-level agent for desktop and mobile

- Sector(s): software, consumer tech, enterprise IT

- Tools/Products/Workflows: generalize Fara-7B’s pixel-in approach to native desktop apps, mobile apps, and hybrid UIs; unify automation across browsers and applications

- Assumptions/Dependencies: OS-level input/output abstractions; screen variability; broader action toolsets beyond web (window management, file I/O)

- Personalized automation via local fine-tuning on user logs

- Sector(s): productivity, privacy tech

- Tools/Products/Workflows: on-device continual learning of frequent tasks; privacy-preserving adaptation of agents to personal browsing habits

- Assumptions/Dependencies: secure data handling; efficient fine-tuning/on-device learning; drift management

- Regulatory frameworks and industry standards for agent safety

- Sector(s): policy, compliance, public sector

- Tools/Products/Workflows: codify “critical point” definitions; mandate audit trails and verifier-backed evidence checks for agent actions; certification programs for CUAs

- Assumptions/Dependencies: multi-stakeholder consensus; test suites and audits; mapping of safety criteria to diverse websites

- Autonomous website QA that adapts to continuous change

- Sector(s): software quality, DevOps

- Tools/Products/Workflows: FaraGen-driven tests that self-refresh via agentic URL exploration; verifiers maintain pass/fail criteria despite UI updates

- Assumptions/Dependencies: resilient exploration agents; effective rubric refresh; governance of flakiness and site variability

- Marketplace of “automation recipes” built from verified trajectories

- Sector(s): software, enterprise IT, consumer tech

- Tools/Products/Workflows: shareable, parameterized tasks (e.g., “compare hotel prices across three sites”) with embedded verification and safety stops; community curation

- Assumptions/Dependencies: standardized recipe format; trust and rating systems; versioning and maintenance

- Enterprise audit and compliance for agent-driven operations

- Sector(s): finance, healthcare, regulated industries

- Tools/Products/Workflows: verifiers as audit engines to produce evidence-backed logs of actions; rubric scoring against SOPs; compliance dashboards

- Assumptions/Dependencies: strong screenshot/evidence capture; mapping rubrics to policies; secure storage and governance

- Healthcare portal navigation with consent-aware automation

- Sector(s): healthcare

- Tools/Products/Workflows: patient-facing agents that find providers, appointments, and benefits info; explicit consent at critical points; eventual handling of login/PHI with verifiable safety

- Assumptions/Dependencies: secure identity integration; HIPAA-compliant logging; robust handling of portal variability

- Education: automated graders and tutors for web-based lab tasks

- Sector(s): education/EdTech

- Tools/Products/Workflows: rubric verifier as an automated grader for multi-step web assignments; agents demonstrate workflows; students review evidence

- Assumptions/Dependencies: carefully designed rubrics; guardrails to avoid sensitive actions; reproducible lab environments

- Mobile and edge deployment for offline digital assistants

- Sector(s): consumer tech, IoT

- Tools/Products/Workflows: optimized Fara-7B variants on smartphones and edge devices; offline task execution with local evidence checking

- Assumptions/Dependencies: model compression; hardware acceleration; battery and performance constraints

- General synthetic interaction data platform beyond the web

- Sector(s): robotics, IoT, software

- Tools/Products/Workflows: extend FaraGen’s multi-agent generation and verification to other interactive domains (e.g., desktop apps, embedded systems, robot UIs)

- Assumptions/Dependencies: domain-specific action spaces; physical interaction simulators; multimodal verifiers adapted to new modalities

- Self-healing RPA with verifier-guided recovery

- Sector(s): enterprise automation

- Tools/Products/Workflows: agents detect looping and failure states, auto-replan, and confirm success via rubrics and multimodal checks; reduce manual maintenance

- Assumptions/Dependencies: robust loop detection; reliable re-planning; high verifier precision to avoid false confidence

- Multimodal, evidence-based research assistants

- Sector(s): academia, journalism, knowledge work

- Tools/Products/Workflows: assistants that gather on-web evidence for claims, attach screenshots, and provide verifier-backed confidence scores; reduce hallucinations in reporting

- Assumptions/Dependencies: curated verifier rubrics per domain; scalable screenshot handling; provenance tracking and storage

Notes on Common Assumptions and Dependencies

- Website variability and drift: frequent UI changes require ongoing updates to task proposals, trajectories, and verifiers.

- Execution stack: reliable headless browsing (e.g., Playwright) and, for data generation, session tools (e.g., Browserbase) significantly affect success rates.

- Safety and compliance: the “critical point” mechanism is essential for safe deployment; moving beyond it requires robust consent and identity management.

- Verifier quality: false positives/negatives exist; thresholds and rubric design must be tuned per task category.

- Device capability: on-device performance depends on available compute; memory constraints limit screenshot history (N=3).

- Login and paywalls: many immediate-use cases assume tasks achievable without authentication; long-term adoption requires secure handling of credentials and payments.

Glossary

- Accessibility tree: A structured representation of a webpage’s UI elements used to expose semantics for assistive technologies and agents; often paired with screenshots for grounding. "The observation from the webpage that the WebSurfer takes in is the accessibility tree and a SoM screenshot"

- AgentInstruct: A method/dataset for generative teaching of agent behaviors and task creation via LLM prompting. "similar to AgentInstruct"

- Agentic: Refers to models or capabilities that can take autonomous actions on behalf of users, beyond passive text generation. "Among the emerging agentic capabilities, Computer Use Agents (CUAs) that can perceive and take actions on the user's computer stand out"

- Alignment Verifier: A text-only LLM judge that checks whether a trajectory’s actions and final response align with the task’s intent. "Alignment Verifier. A text-only verifier designed to judge whether the actions taken and final response of a trajectory aligns with the given task."

- Azure Machine Learning: A cloud platform used to orchestrate and parallelize large-scale data generation jobs. "on Azure Machine Learning"

- Backbone model: The underlying multimodal LLM that powers an agent’s reasoning and actions. "use different multimodal LLMs as the backbone model for the WebSurfer"

- Browserbase: A managed browser infrastructure service used to stabilize sessions and improve data generation yield. "using Browserbase improves successful trajectory yield by more than 3x"

- Chain-of-thoughts: The intermediate reasoning text a model produces to articulate steps and decisions before executing actions. "thoughts/chain-of-thoughts"

- ClueWeb22: A large public web crawl corpus used as a source of seed URLs for task proposal. "ClueWeb22 URL Corpus"

- Context window: The portion of model input that maintains recent history of observations, thoughts, and actions. "keeping the full history in the context window becomes computationally intensive"

- Critical point: A state where proceeding requires user permission or would commit a binding, hard-to-reverse action; agents must stop or get explicit approval. "A critical point is any binding transaction or agreement that would require the user's permission"

- DOM parsing: Programmatic extraction of a webpage’s Document Object Model; considered brittle for general web agents. "This avoids dependence on brittle DOM parsing"

- Distilling: Training a smaller, unified model by learning from outputs/behaviors of larger or multi-agent systems. "We opt to train a single native CUA model by distilling from these multi-agent trajectories."

- Fault tolerance: System design techniques that enable robust recovery from web browsing errors and timeouts. "fault tolerance accounted for the remainder"

- Fara-7B: A compact 7B-parameter, screenshot-only native computer-use agent that outputs low-level actions like clicks and typing. "We use this data to train Fara-7B"

- FaraGen: A synthetic data generation engine that proposes, solves, and verifies multi-step web tasks at scale. "we introduce FaraGen, a novel synthetic data generation system for multi-step web tasks"

- Frontier models: State-of-the-art, often large and expensive LLMs used as strong baselines or solvers. "much larger frontier models"

- Gold reference answers: Ground-truth solutions used to evaluate tasks; often unavailable for open-web agent tasks. "Often, gold reference answers exist for neither of these scenarios."

- Grounded actions: Actions tied to specific page elements or coordinates to ensure the behavior corresponds to visible UI state. "reliably predicts grounded actions"

- Hallucinations: Model-generated content not supported by evidence or the environment’s state; must be filtered or verified. "filtering out hallucinations or execution errors"

- Headless Playwright instance: A non-UI browser automation session used to run scalable, parallel task-solving. "encapsulates a headless Playwright instance"

- LLM judge: An LLM prompted to evaluate and score a trajectory’s correctness from different perspectives. "Each verifier is an LLM judge"

- LLM verifiers: LLM-based evaluation modules that validate whether trajectories satisfy tasks and avoid errors. "We use LLM verifiers to validate trajectory outcomes against the original intent"

- Magentic-One: A generalist multi-agent framework used to orchestrate task solving with specialized agents. "built on Magentic-One"

- Magentic-UI: A UI-focused extension/agent set used to attempt web tasks and generate demonstrations. "extends the Magentic-One and Magentic-UI agents"

- Memorize: An agent action that stores salient information for later use within a trajectory to reduce re-reading or hallucinations. "Memorize, which lets the WebSurfer record a piece of information that it can keep in its context for later"

- Multi-agent system: A coordinated set of specialized agents (e.g., Orchestrator, WebSurfer, Verifiers) that solve tasks end-to-end. "a multi-agent system built on Magentic-One"

- Multi-modal LLM agent: An agent that processes both text and images (e.g., screenshots) for planning and action selection. "instantiating a multi-modal LLM agent to traverse the website"

- Multimodal Verifier: An evidence-based checker that uses salient screenshots and final responses to validate task completion. "Multimodal Verifier. This verifier inspects the screenshots and final response of the trajectory"

- Online-Mind2Web: A benchmark for evaluating web agents on real online tasks. "Online-Mind2Web"

- Open-weight: A release model where trained weights are publicly available for use and deployment. "We are making Fara-7B open-weight"

- Orchestrator: The planning and supervisory agent that guides WebSurfer, enforces critical points, and manages progress. "The purpose of the Orchestrator is to guide progress of the WebSurfer"

- Pareto frontier: The trade-off curve showing optimal balance between competing metrics (e.g., accuracy vs. cost). "Fara-7B breaks ground on a new Pareto frontier"

- Pixel-in, action-out: A formulation where the agent consumes screenshots and directly predicts low-level actions (e.g., clicks). "Fara-7B adopts a 'pixel-in, action-out' formulation"

- Playwright: A browser automation library enabling scripted actions like click, type, and navigation. "via Playwright actions, like click and type."

- Rubric Verifier: A verifier that generates and applies task-specific scoring rubrics to assess partial and full completion. "Rubric Verifier. The Rubric Verifier generates a rubric for each task"

- Set-of-Marks (SoM) Agent: An agent paradigm that uses accessibility-tree elements and their marked regions for grounding actions. "Set-of-Marks (SoM) Agents"

- SoM screenshot: A screenshot with bounding boxes for accessibility-tree elements to visually ground actions. "a SoM screenshot with the bounding boxes of the accessibility tree elements annotated in the image"

- Tool call: A structured action output by the model that invokes predefined tools (e.g., click, type, scroll). "represented as a tool call"

- Trajectory Verification: The stage that uses multiple verifiers to ensure candidate trajectories truly satisfy tasks. "Trajectory Verification to filter which candidate trajectories successfully completed the task"

- Tranco: A public URL ranking corpus used as a source of seed websites. "Tranco URL Corpus"

- UI-TARS-1.5-7B: A comparable 7B web agent baseline used in cost and step-count comparisons. "Both Fara-7B and UI-TARS-1.5-7B have the same token cost"

- UserSimulator: An agent that provides simulated user inputs or follow-up tasks at stopping points or critical points. "The UserSimulator when activated, allows the data generation pipeline to resume from a critical point"

- Vision-centric CUAs: Computer-use agents that rely primarily on visual inputs (screenshots) rather than DOM or accessibility scaffolds. "vision-centric CUAs exhibit stronger cross-site generalization"

- WebSurfer: The agent that directly interacts with the browser, executes actions, and reports state back to the Orchestrator. "The WebSurfer takes this instruction and an observation from the browser"

- WebTailBench: A benchmark of under-represented real-world web tasks used to evaluate agent generalization. "We are releasing WebTailBench"

- WebVoyager: A benchmark for end-to-end web agent performance and success rates. "WebVoyager accuracy and cost of Fara-7B"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.