Deep Whole-body Parkour

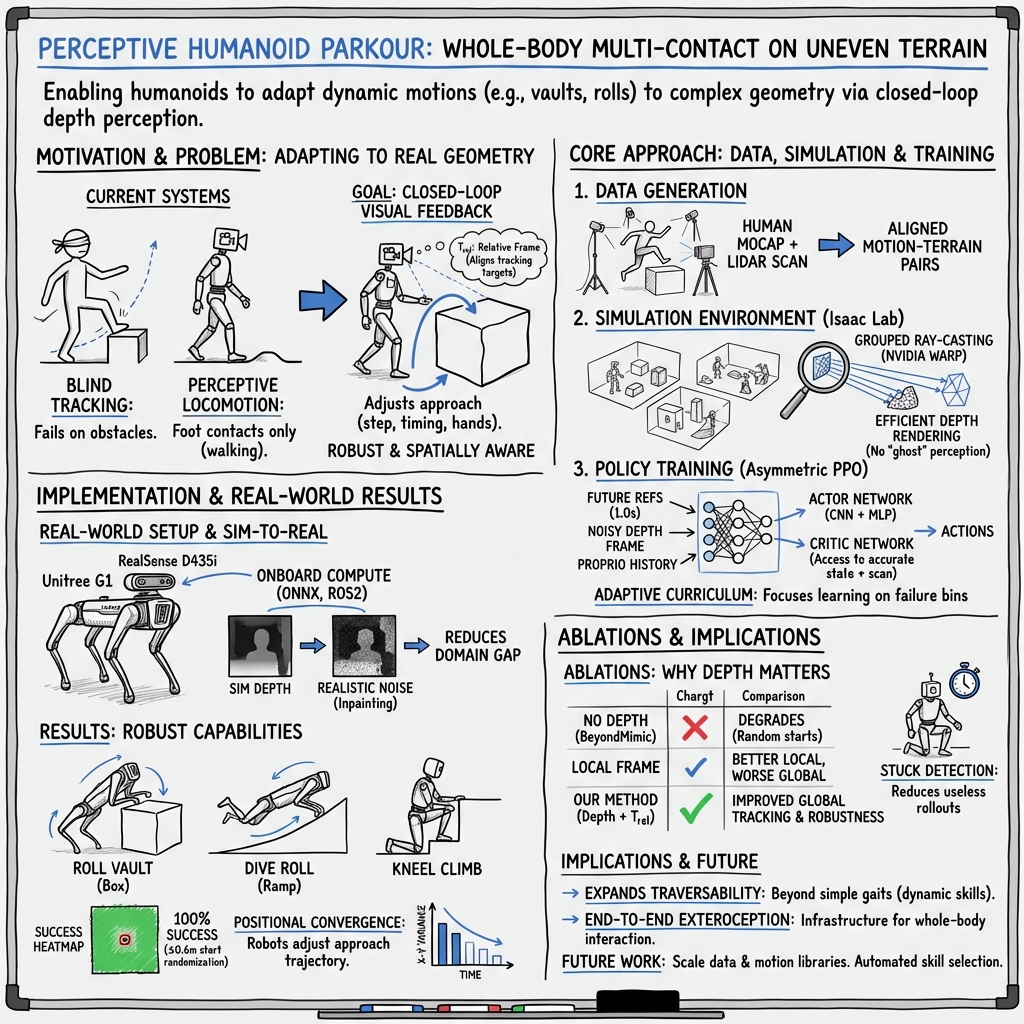

Abstract: Current approaches to humanoid control generally fall into two paradigms: perceptive locomotion, which handles terrain well but is limited to pedal gaits, and general motion tracking, which reproduces complex skills but ignores environmental capabilities. This work unites these paradigms to achieve perceptive general motion control. We present a framework where exteroceptive sensing is integrated into whole-body motion tracking, permitting a humanoid to perform highly dynamic, non-locomotion tasks on uneven terrain. By training a single policy to perform multiple distinct motions across varied terrestrial features, we demonstrate the non-trivial benefit of integrating perception into the control loop. Our results show that this framework enables robust, highly dynamic multi-contact motions, such as vaulting and dive-rolling, on unstructured terrain, significantly expanding the robot's traversability beyond simple walking or running. https://project-instinct.github.io/deep-whole-body-parkour

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper shows how a humanoid robot can do “parkour-like” moves—such as vaulting over a box or doing a dive roll—by looking at the world with a depth camera and adjusting its movements on the fly. Instead of only walking or running and only using its feet, the robot learns to use its whole body (hands, arms, legs) to make contact with obstacles safely and accurately.

Key questions the researchers asked

- Can a robot learn complex, athletic, whole-body skills that depend on the exact shape and position of obstacles (not just flat ground)?

- Does giving the robot vision (a depth camera) help it place its hands and feet correctly, even if it starts from the “wrong” spot?

- Can this be trained in simulation and then work on a real robot, indoors and outdoors, without needing perfect GPS-like positioning?

How they did it (in simple terms)

Think of the robot like a gymnast who watches the obstacle before moving. The team combined two worlds:

- “Motion tracking” (copying a human’s movement), and

- “Perceptive control” (using cameras to react to the environment).

Here’s the overall approach:

- Collect human examples tied to real obstacles: The team recorded experts doing parkour moves (vaults, dive rolls, climbs) with motion capture. At the same time, they scanned the environment (like the box or rail) to get its exact 3D shape. This creates perfectly matched “move + obstacle” pairs.

- Retarget the moves to the robot: They adapted the human motions to fit the robot’s body (so the robot’s joints and limb lengths can actually perform them).

- Train in a big simulated world: They built many virtual scenes by placing the scanned obstacles in different spots. The robot sees a depth image (like a grayscale picture where pixel brightness means how far things are) and practices the moves using reinforcement learning (RL)—a trial-and-error method where the robot gets rewards when it moves like the demonstration and succeeds with the obstacle.

- A “relative frame” for fair scoring: To judge how well the robot is copying the motion, they compare poses using a smart in-between viewpoint that mixes where the robot is now with where the reference motion expects it to be. This keeps the scoring stable, even if the robot’s starting position is a bit off.

- Practice more where it fails: If the robot keeps messing up a certain part of a move (for example, the jump timing), the training system resets it to practice that difficult slice more often. This speeds up learning, like a coach repeating the tricky section of a routine.

- Make simulated vision realistic: Real depth cameras have noise (blurry patches, missing pixels). They added similar “messiness” to the simulated depth images and used fast image-fixing (inpainting) so the robot wouldn’t be surprised by the real world later.

- Fast, isolated vision in sim: They built a speedy “virtual depth camera” so thousands of robots can train in parallel without “seeing” each other’s worlds by accident.

- Real-world deployment: The final policy (the robot’s brain) runs on a Unitree G1 humanoid at 50 frames per second using an onboard depth camera. A simple state machine selects which skill to run. Importantly, the robot does not need accurate global positioning (odometry); it aligns itself with what it sees.

What they found and why it matters

Here are the main takeaways from their experiments:

- Vision makes the difference for tricky skills:

- With depth input, the robot can adjust its steps and timing as it approaches an obstacle. That means it can start from different spots and still place its hands and feet correctly to vault or dive-roll.

- Without depth (just blindly copying a motion), the robot needs a perfect starting position; otherwise, it may mistime the jump or miss the hand contact.

- Robust across places and setups:

- The same learned policy handled different indoor and outdoor environments, and it worked even when the robot’s starting point varied by more than what it saw during training.

- In simulation tests, groups of robots starting from different positions “converged” toward the obstacle correctly and finished the moves.

- Handles visual distractions reasonably well:

- The team added new objects into scenes (not seen in training) to test whether the robot gets confused by extra stuff. The policy generally stayed on track. Some distractors increased tracking error a bit (especially big flat platforms that change the motion’s physics), but overall success stayed strong.

- Training recipe matters:

- Using depth vision, the smart “relative” scoring, and “practice where you fail” all helped.

- A “stuck detection” rule (ending training trials that are impossible) stopped the robot from wasting time learning from unwinnable scenarios.

- Works on a real humanoid:

- They ran everything on a Unitree G1 robot with a RealSense depth camera at 50 Hz, switching between walking and parkour policies as needed. No precise global localization system was required.

Why this is important:

- This approach expands what humanoid robots can do in the real world—from simple walking to agile, contact-rich moves that humans use in tight, cluttered spaces. That’s key for tasks like disaster response (climbing debris), warehouse work (navigating racks and platforms), or home help (reaching over furniture safely).

What this could lead to next

- Bigger skill libraries: The same training framework could be used to learn many more whole-body skills that rely on contact and timing.

- More adaptation: Future robots could choose and blend skills automatically based on what they see, not just run one chosen motion.

- Better perception: Combining depth with other sensors (like RGB cameras or semantic understanding) could help the robot understand not just shapes, but also which surfaces are safe to touch.

In short, the paper shows a practical way to teach humanoid robots to “see and do” complex, athletic movements with their whole body—making them more capable, flexible, and useful in the real world.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper. These are framed to be actionable for follow-up research.

- Missing quantitative real-world evaluation: no per-motion, per-terrain success rates, number of trials, or confidence intervals reported for hardware experiments.

- Lack of task-relevant metrics beyond MPJPE: no measurements of contact timing accuracy, hand/foot placement error on obstacles, slippage incidence, impact forces/impulses, or safety margins.

- Limited skill and terrain diversity: only four skills across three terrains; scalability to larger, parameterized skill libraries and a broader spectrum of obstacle geometries is untested.

- Manual motion selection at deployment: skill choice is driven by a hand-crafted state machine; no autonomous perception-to-skill selection or parameterization based on sensed geometry.

- Generalization to obstacle parameters not characterized: no systematic sweeps over obstacle height/width/tilt/gap distance with performance curves to validate claimed adaptability.

- Distractor robustness tested only for static, simple shapes: no evaluation with dynamic obstacles (moving humans/objects), time-varying occlusions, or changing illumination.

- Depth-only, single-frame perception: no temporal fusion, multi-view sensing, or active perception head motion; sensitivity to depth latency, frame drops, and jitter is unreported.

- RealSense-specific failure modes unaddressed: outdoor IR saturation, strong sunlight, reflective surfaces, and rolling-shutter artifacts are not modeled or evaluated.

- Sim-to-real depth gap modeling is simplistic: Gaussian/patch noise and inpainting are used without ablations covering stereo-matching errors, exposure changes, motion blur, or multipath interference.

- Self-occlusion handling unclear: no method described for removing robot-body pixels in depth (e.g., self-segmentation), yet real sensors will see arms/hands crossing the FOV.

- No study on camera calibration robustness: sensitivity to intrinsics/extrinsics errors, head-mount pose drift, and misalignment between simulated and real camera geometry is unknown.

- No odometry reliance raises scalability questions: how to handle long approach distances, multi-obstacle routes, and accumulated drift without global localization remains open.

- Reward shaping choices underexplored: the benefits/trade-offs of the proposed relative-frame reward versus baselines across tasks and in real deployments lack systematic analysis.

- Curriculum (adaptive sampling, stuck detection) evaluated mainly in simulation: real-world gains in reliability, sample efficiency, and training stability are not quantified.

- Baseline comparisons limited: no head-to-head with model-based MPC/planning approaches, perceptive planners with odometry, or imitation policies with explicit environment models.

- Actuation and control gap unclear: whether the policy outputs torques or low-level targets on hardware, and how sim actuation matches real servos/PD controllers, is not detailed.

- Contact physics robustness untested: no domain randomization or sensitivity analysis over friction/compliance/restitution; behavior on slippery or high-compliance surfaces is unknown.

- Safety and hardware wear not assessed: peak joint torques, thermal limits, and repeated impact loads (e.g., dive-rolls) are not monitored or mitigated in evaluation.

- Failure handling and recovery absent: behavior under missed hand placement, partial slips, or contact timing errors, and the ability to abort/recover mid-skill, are not analyzed.

- Skill sequencing not addressed: transitioning between multiple skills to traverse extended courses, with closed-loop re-planning, remains an open problem.

- Policy architecture underexplored: alternatives like attention over depth, point-cloud/voxel encoders, or implicit occupancy fields are not compared; benefits of temporal depth stacks are unknown.

- Compute and scaling limits not reported: training time, GPU budget, environment count limits, mesh complexity bounds, and memory/throughput ceilings of the custom ray-caster are omitted.

- Cross-robot portability untested: transfer to other humanoids (different morphology, actuation, camera placement) and required adaptation procedures are not evaluated.

- Data pipeline scalability limited: retargeting requires manual keyframe adjustments; automated contact labeling/validation and throughput statistics for larger datasets are missing.

- Real-world convergence and success heatmaps absent: the success-rate heatmaps are shown in simulation; equivalent maps/statistics in hardware tests are not provided.

- Interface design remains narrow: reliance on reference motion clips sidesteps semantic affordance understanding; integrating semantics (e.g., graspable edges vs unsafe surfaces) is unexplored.

- Latency budget and synchronization uncharacterized: end-to-end sensing-to-action latency, its variability, and its impact on dynamic skills at 50 Hz are not measured.

- Future-reference dependence not ablated: how many future frames and horizon length are necessary/sufficient, and their effect on robustness and sim-to-real, are not studied.

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper introduces a perceptive whole-body motion tracking framework that integrates exteroceptive depth sensing with data-driven control to enable humanoid robots to perform dynamic, multi-contact maneuvers (e.g., vaulting, dive-rolling, kneel-climbing) on unstructured terrain. Key innovations include:

- A motion–terrain paired dataset pipeline (human parkour MoCap aligned with LiDAR scene meshes) and retargeting to a physical humanoid.

- A massively parallel, grouped ray-casting engine (NVIDIA Warp) for isolated multi-agent depth rendering with a 10× speedup.

- A training recipe combining a “relative frame” tracking formulation, asymmetric PPO with future motion references, adaptive sampling via failure-based curriculum, and stuck detection.

- Robust sim-to-real transfer for depth perception (noise models and GPU-based inpainting), onboard 50 Hz deployment via ONNX, and an odometry-free controller using only IMU-aligned heading and depth.

Below, we translate these findings into practical, real-world applications across industry, academia, policy, and daily life, grouped by readiness.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now or with minor engineering integration, leveraging the paper’s methods and infrastructure.

- Robotics R&D demos and pilot deployments in controlled environments (sector: robotics, entertainment)

- Use case: Showcasing dynamic, multi-contact traversal of obstacles (vaults, dives, scramble) by humanoids in labs, trade shows, and theme-park-style demonstrations.

- Tools/workflows: The perceptive whole-body controller with depth input; motion state-machine selector; ONNX-based 50 Hz inference; odometry-free relative-frame tracking for rapid setup.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to a capable humanoid platform (e.g., Unitree G1), reliable depth sensing (RealSense D435i or similar), safety supervision, and curated motion references.

- Simulation pipeline acceleration for multi-agent training (sector: software/tools, robotics)

- Use case: Integrate the “Massively Parallel Grouped Ray-Casting” into existing RL training stacks to scale multi-agent depth rendering with isolation (no “ghost” robots across environments).

- Tools/products: A reusable GPU ray-casting library (NVIDIA Warp) with collision group mapping; Isaac Lab integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU capacity, mesh instancing support, accurate collision group assignment; compatibility with existing simulators.

- Motion–terrain paired dataset creation (sector: robotics, computer graphics/animation, education)

- Use case: Build high-fidelity datasets coupling human demonstrations with aligned obstacle geometry to train contact-rich skills or produce physically grounded animations.

- Tools/workflows: MoCap + LiDAR alignment, retargeting (e.g., GMR), canonical obstacle mesh extraction, procedural instantiation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to MoCap studio and LiDAR scanning (e.g., iPad Pro), retargeting expertise, IP/consent for human motion capture and scanned environments.

- Odometry-free deployment templates for mobile robots (sector: robotics)

- Use case: Rapid deployment of dynamic behaviors without global localization—using the relative-frame formulation and IMU-heading alignment to tolerate starting-position variance.

- Tools/workflows: ROS2 nodes for separate depth acquisition and inference; CPU binding to isolate logging (rosbag) from inference; GPU OpenCV inpainting for real-time depth cleanup.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable IMU, consistent camera calibration, careful start-heading alignment; process scheduling best practices on embedded compute.

- Academic benchmarking and course labs (sector: academia/education)

- Use case: Curriculum modules on “perception-integrated motion tracking,” comparing blind tracking vs. depth-guided control, and ablations (stuck detection, adaptive sampling).

- Tools/workflows: Publicly available infrastructure (sim environment, training recipes, evaluation metrics like success-rate heatmaps and MPJPE-Global/Base).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to simulators (Isaac Lab) and GPUs; safety protocols for any real-robot exercises.

- Safety and QA protocols for dynamic contact-rich motion (sector: policy, robotics QA)

- Use case: Establish lab-level test protocols—grid-based success-rate heatmaps, distractor robustness tests (walls, planes, wide objects)—for certifying motion reliability before public demos.

- Tools/workflows: Batch simulation with controlled initialization variance and distractor scenarios; MPJPE-based evaluation in global/base frames.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear go/no-go thresholds; incident reporting; physical safety barriers and spotters.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, safety validation, and/or integration with broader autonomy stacks and operational processes.

- Search and rescue in cluttered or collapsed structures (sector: public safety, robotics)

- Use case: Humanoids negotiating rubble via multi-contact traversal, hand-assisted climbing, and dynamic crossing of gaps to reach victims.

- Tools/products: Perceptive whole-body controllers plus task-layer planning; robust depth sensing (possibly multi-modal: LiDAR + stereo); fail-safe policies and fall detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Enhanced robustness to debris, dust, low light; improved actuation, protective shells; certified safety procedures and liability coverage.

- Construction and industrial inspection (sector: construction, energy, infrastructure)

- Use case: Navigating scaffolds, ladders, catwalks, and cluttered sites; reaching inspection targets while handling uneven surfaces and constrained spaces.

- Tools/products: Integrated multi-contact skill library; site-specific motion–terrain datasets; integration with BIM/site maps; remote teleoperation fallback.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware durability; compliance with job-site safety standards; reliable sensing in outdoor, reflective, or weather-prone conditions.

- Warehousing and logistics (sector: logistics, retail)

- Use case: Crossing pallets, steps, and mixed-height obstacles; assisting with shelf access where stair/ladder usage is required; dynamic path repair in temporary layouts.

- Tools/products: Warehouse-specific training scenarios; high-level task orchestration with perception-integrated motion skills; interoperability with AMR fleets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Collision avoidance in busy environments; guardrails preventing unsafe parkour near people; ROI analysis vs. simpler wheeled solutions.

- Assistive and service humanoids for complex homes and healthcare settings (sector: healthcare, consumer robotics)

- Use case: Safely navigating clutter, varying floor transitions, or small barriers; using hands for support during mobility assistance.

- Tools/products: Human-aware motion constraints; perception-informed fall prevention; certified, conservative variants of multi-contact skills.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clinical safety validation; ethical and privacy safeguards; personalization to user mobility and environment geometry.

- Generalist humanoid controllers with perception (sector: software/AI platforms, robotics)

- Use case: Scale up to “foundation” controllers that unify large motion libraries with scene-aware adaptation, enabling rapid task composition (locomotion + manipulation + traversal).

- Tools/products: Cloud training platforms with grouped ray casting; extensive motion–terrain datasets; curriculum learning pipelines; model distillation for edge deployment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant compute and data; standardized evaluation suites; modular skill selection and failure recovery.

- Teleoperation–autonomy hybrid workflows (sector: teleoperations, field robotics)

- Use case: Operators trigger high-level goals while autonomous controllers handle dynamic multi-contact traversal, with on-the-fly motion retargeting to现场 geometry.

- Tools/products: Unified control interfaces (e.g., TWIST/OmniH2O-style teleop fused with perception-aware tracking); latency-tolerant depth pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable comms; shared autonomy arbitration; operator training and ergonomic interfaces.

- Standards and regulation for dynamic humanoid mobility (sector: policy/regulation)

- Use case: Developing safety standards for contact-rich motions (acceptable impact forces, sensor latency bounds, fail-safe triggers), and guidance on dataset curation (scanning/privacy).

- Tools/products: Certification protocols, compliance tests (distractor robustness, success heatmaps), incident logging standards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder coordination (manufacturers, insurers, regulators); harmonization across regions.

- Data marketplaces for motion–terrain pairs (sector: data/AI ecosystems, media)

- Use case: Curated repositories of high-quality, aligned motion and environment geometry for training robots and generating physically plausible animation assets.

- Tools/products: Anonymization tools for scanned spaces; licensing frameworks; standardized metadata (contact events, geometry descriptors).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal frameworks for scanning private spaces; quality control; interop with simulators and graphics engines.

Cross-cutting dependencies and assumptions

- Hardware capabilities: Sufficient DOF/torque, ruggedized design, and protective measures for dynamic contact-rich motion.

- Sensing robustness: Depth sensors must handle reflections, motion blur, and outdoor lighting; may require sensor fusion (stereo + LiDAR).

- Compute and deployment: Embedded inference at ≥50 Hz, robust process isolation, and real-time depth filtering (GPU inpainting or equivalent).

- Safety and ethics: Human-aware motion constraints, transparent risk assessments, and adherence to privacy when scanning environments.

- Data and training: Access to representative motion–terrain pairs; scalable training infrastructure; reproducible evaluation protocols.

Glossary

- Acceleration Structure: A spatial data structure built to speed up ray–geometry intersection queries during rendering. "Phase 1: Acceleration Structure Construction (Pre-compute)"

- Adaptive Sampling: A training strategy that adjusts which motion segments are sampled based on observed failures to focus learning on difficult parts. "We employ an adaptive sampling strategy to facilitate curriculum learning."

- Asymmetric Actor-Critic: A reinforcement learning setup where the actor and critic receive different observations (e.g., critic gets privileged information) to stabilize training. "Through teacher-student frameworks or asymmetric actor-critics, policies learn to estimate terrain properties implicitly"

- Asymmetric PPO: A variant of Proximal Policy Optimization where the actor and critic have asymmetric inputs (e.g., critic includes privileged signals). "We adopt the policy training using asymmetric PPO."

- Axis Angle: A rotation representation that encodes orientation as a single rotation about a unit axis. "Global root rotation reward based on rotation difference to the reference rotation in axis angle."

- CNN: Convolutional Neural Network; a deep learning architecture commonly used to encode images. "with a CNN encoder encoding the depth image"

- Collision Group ID: An identifier used to partition objects into visibility or collision groups so agents perceive only relevant meshes. "each robot is assigned a unique collision group ID to ensure disjoint perception."

- Curriculum Learning: A training approach that orders tasks from easier to harder to improve learning efficiency. "We employ an adaptive sampling strategy to facilitate curriculum learning."

- Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL): A class of methods combining deep neural networks with reinforcement learning to learn policies from interaction. "Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has fundamentally transformed the landscape of legged robotics"

- Degrees of Freedom (DOF): The number of independent actuated or kinematic parameters that define a robot’s configuration. "Unitree G1 29-DOF, September 2025 version."

- Depth Image: An image whose pixel values encode distance from the sensor to surfaces in the scene. "We train our policy using synchronized depth image observations."

- Exteroception: Sensing modalities that measure external environment properties (e.g., depth, height maps). "We train the policy using both proprioception and exteroception, specifically through depth image."

- Height Map: A 2D grid representation of terrain elevation used for perception and planning. "By fusing proprioceptive data with exteroceptive observationsâsuch as depth images or height mapsârobots can now adapt their gait patterns to unstructured terrain in real-time"

- Height Scan: A sensor-derived profile of terrain elevation used by the critic to assess value. "height-scan to the terrain"

- IMU: Inertial Measurement Unit; a sensor providing accelerations and angular rates used to estimate orientation and motion. "based on the real-time IMU readings of the robot"

- Inpainting: An image processing technique that fills in missing or corrupted regions to produce plausible content. "We use the inpainting algorithm from a GPU-based OpenCV implementation."

- Isaac Lab: NVIDIA’s simulation platform for robotics used to build massive-parallel training environments. "we integrate these assets into NVIDIA Isaac Lab to create a massive-parallel training environment."

- LiDAR: Light Detection and Ranging; a sensor that measures distance via laser pulses to reconstruct 3D geometry. "LiDAR-enabled iPad Pro (via the 3D Scanner App)."

- Markov Decision Process (MDP): A formalism for sequential decision-making defined by states, actions, transitions, and rewards. "We formulate the training environment as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and employ an adaptive sampling strategy"

- Mesh Instancing: Rendering or simulation technique that reuses a single mesh prototype across multiple transformed instances to save memory. "To maximize memory efficiency, we employ mesh instancing;"

- MLP: Multilayer Perceptron; a feedforward neural network composed of stacked fully connected layers. "feed to a 3 layer MLP network"

- MPJPE: Mean Per Joint Position Error; a metric quantifying average joint position deviation from reference. "Each motion is evaluated using two metrics ( and )."

- Multi-Agent Training: Training multiple agents concurrently with isolated observations within a shared simulation. "Massively Parallel Ray-Caster for Isolated Multi-Agent Training"

- Multi-Contact: Motions involving intentional contact with the environment using multiple body parts beyond feet. "multi-contact motionsâsuch as vaulting and dive-rollingâon unstructured terrain, significantly expanding the robot's traversability"

- Motion Retargeting: Adapting human motion capture trajectories to a robot’s morphology and constraints. "Motion Retargeting"

- Nvidia Warp: A GPU-accelerated computation library used here to implement high-performance ray casting. "utilizing Nvidia Warp."

- Occupancy: The presence of physical geometry in space as perceived by sensors, often used to adapt motion. "visual occupancy of the environment."

- Odometry: Estimation of a robot’s change in position and orientation over time. "without any odometry system"

- ONNX: Open Neural Network Exchange; a runtime/format for deploying neural networks across platforms. "we adopt ONNX as our neural network accelerator."

- PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization): A policy gradient algorithm that stabilizes updates via clipped objective functions. "We adopt the policy training using asymmetric PPO."

- Proprioception: Sensors measuring internal robot states (e.g., joint positions, velocities, torques). "We train the policy using both proprioception and exteroception"

- Ray-Casting: Tracing rays through a scene to compute intersections for generating depth or visibility. "Massively Parallel Grouped Ray-Casting"

- Ray Marching: Iterative traversal along a ray to find the nearest intersection with scene geometry. "during the ray-marching phase"

- RealSense: Intel’s RGB-D camera line used here for real-time depth sensing on the robot. "We deploy the policy using 50Hz depth image using RealSense."

- Relative Frame: A hybrid reference frame combining parts of the robot’s current pose with parts of the motion reference pose. "By defining the relative frame "

- ROS2: Robot Operating System 2; a middleware framework for building robotics applications. "we deploy our entire inference system using ROS2"

- Rosbag: A ROS utility for recording and replaying message topics for logging and analysis. "we run rosbag recording in a separate process."

- Sim-to-Real Gap: The mismatch between simulation and real-world conditions that can hinder policy transfer. "Bridging sim-to-real gap in depth perception"

- Stroboscopic Photography: Imaging technique capturing motion at intervals to visualize dynamics. "using stroboscopic photography."

- Stuck Detection: A mechanism to terminate or truncate episodes when the robot becomes stuck in unsolvable states. "Early Timeout with Stuck Detection"

- Teacher-Student Framework: A training approach where a privileged “teacher” guides a “student” policy with limited observations. "Through teacher-student frameworks or asymmetric actor-critics, policies learn to estimate terrain properties implicitly"

- Traversability: The capability of a robot to move through and interact with diverse terrains and obstacles. "expanding the robot's traversability beyond simple walking or running."

- Yaw: The rotation about the vertical axis representing heading in 3D orientation. "but the same yaw angle as ."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.