Deriving Neural Scaling Laws from the statistics of natural language

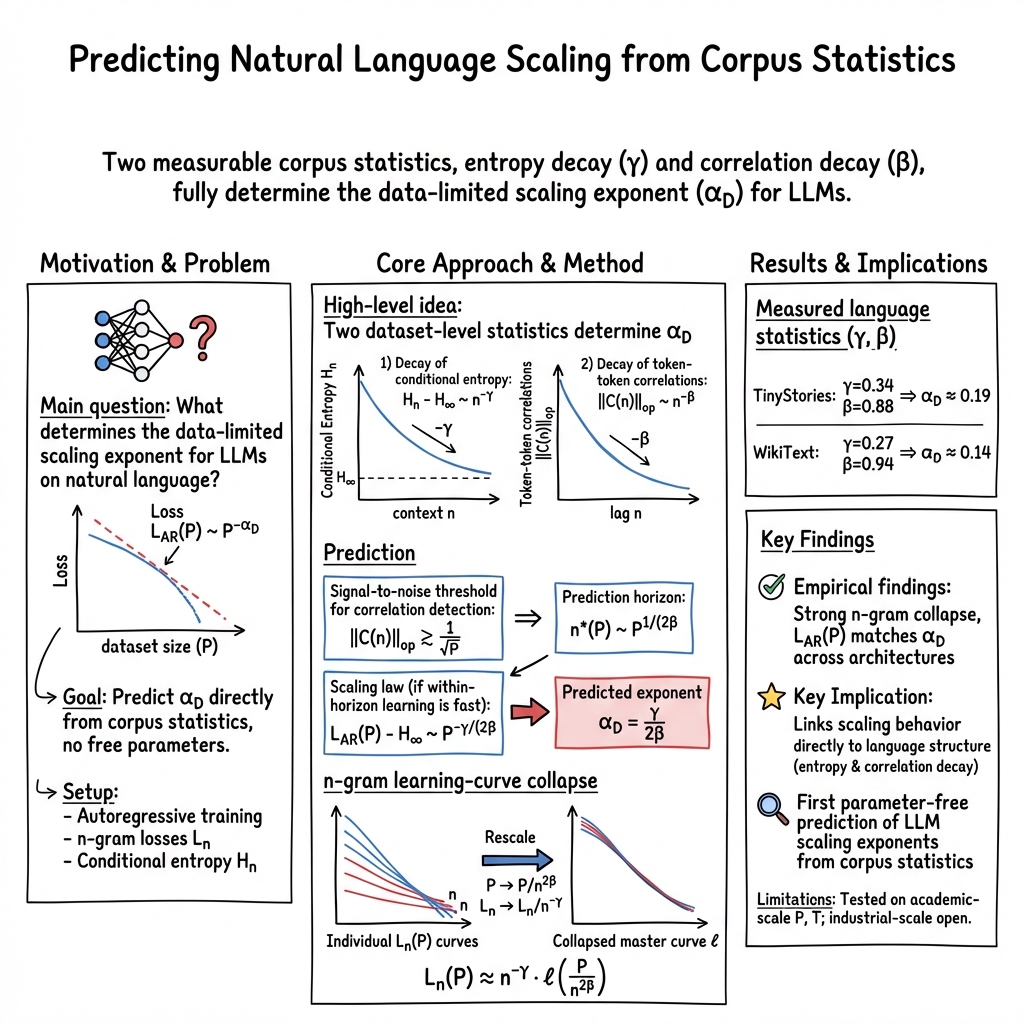

Abstract: Despite the fact that experimental neural scaling laws have substantially guided empirical progress in large-scale machine learning, no existing theory can quantitatively predict the exponents of these important laws for any modern LLM trained on any natural language dataset. We provide the first such theory in the case of data-limited scaling laws. We isolate two key statistical properties of language that alone can predict neural scaling exponents: (i) the decay of pairwise token correlations with time separation between token pairs, and (ii) the decay of the next-token conditional entropy with the length of the conditioning context. We further derive a simple formula in terms of these statistics that predicts data-limited neural scaling exponents from first principles without any free parameters or synthetic data models. Our theory exhibits a remarkable match with experimentally measured neural scaling laws obtained from training GPT-2 and LLaMA style models from scratch on two qualitatively different benchmarks, TinyStories and WikiText.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper tries to explain a simple rule behind how LLMs (like GPT) get better when you give them more text to learn from. These rules are called “scaling laws.” The authors show that in the “data-limited” situation—when the main thing holding a model back is not having enough training text—you can predict how fast a model improves just by measuring two basic statistics of the language itself. Even better, their prediction matches real experiments on popular datasets and model types.

What questions did the researchers ask?

- Can we predict how quickly a LLM’s error goes down as we give it more training tokens, using only properties of natural language (and not special assumptions about the model)?

- Are there simple, measurable features of a text dataset that determine this improvement rate?

- Do these predictions match what actually happens when you train models like GPT-2 or LLaMA on real text?

How did they study it? (With simple analogies)

Think of teaching a model to guess the next word in a sentence. The model looks at some number of previous words (its “context”) and tries to be less and less surprised about what comes next.

The authors focus on two language statistics you can think of like “rules of the road” for how language works:

- How surprise drops with more context (γ, “gamma”)

- Analogy: When you read more of a sentence, you’re less surprised by the next word. If surprise drops quickly as you see more words, γ is larger. If it drops slowly, γ is smaller.

- In technical terms, this is how the next-word uncertainty (conditional entropy) decreases when you let the model look further back.

- How word relationships weaken with distance (β, “beta”)

- Analogy: The further apart two words are, the weaker their connection usually is. If far-away words still influence each other a lot, the decay is slow and β is smaller; if that influence fades quickly, β is larger.

- In technical terms, this is how the strength of correlations between tokens drops as the gap between them grows.

Next, they introduce the idea of a “prediction horizon,” which is how far back the model can effectively use context given how much data it has seen. With little data, the model can only trust short-range patterns; with more data, it can detect and use longer-range patterns. The authors show that this horizon grows like a power of the total number of training tokens, and that most of the improvement in test performance comes from being able to use longer context, not from tiny refinements within a fixed short context.

Finally, they connect the two statistics (γ and β) to a single prediction for how test loss improves with data. They derive a simple formula for the data-limited scaling exponent:

- The improvement rate exponent is α_D, given by:

They then test this on real data by:

- Measuring γ and β directly from two datasets (TinyStories and WikiText).

- Training GPT-2–style and LLaMA–style models from scratch on those datasets.

- Checking if the observed improvement with more data matches the predicted exponent.

What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the key findings:

- A simple formula predicts learning speed: Once you measure γ (how fast surprise drops with context) and β (how fast word-to-word connections fade with distance) from a dataset, you can predict the rate at which a model’s test loss falls as you add more training tokens. The predicted rate is .

- The prediction matches real training: They trained GPT-2– and LLaMA–style models on TinyStories and WikiText and found that the test loss decreases with more data at almost exactly the predicted rate—without any extra tuning or hidden constants. That means the language’s own statistics determine how fast models can improve when data is the bottleneck.

- “Curve collapse”: When they looked at the model’s performance using exactly n previous tokens (like a next-word guess using 5, 10, 20 words of context), and plotted those results in the right scaled units, all the different curves neatly lined up onto a single master curve. This is strong evidence that the main thing changing with more data is how far back the model can “see,” not how much better it gets within a fixed small window.

Why it matters:

- It links the structure of language directly to how fast models learn from more data.

- It provides a practical, theory-backed way to predict returns on collecting more text.

- It works across different model architectures tested, suggesting the result is broadly useful.

What could this change or lead to?

- Better planning for training: If you can measure γ and β for a new dataset, you can forecast how much more data will help before you even start large-scale training. This can save time and compute.

- Insights for model design: The work suggests that modern deep models quickly make good use of whatever context they can reliably detect. The main limiter is how far back they can “trust” patterns given the available data. That points researchers to methods that unlock longer useful horizons efficiently.

- A deeper link between language and learning: The results show that the speed of learning is not just a property of the model; it’s heavily shaped by language’s own patterns. Future work might find other “universality classes” of models that learn even faster from the same data—or designs that make better use of sparse, long-distance cues.

In short, this paper gives a clear, testable rule connecting the statistics of natural language to how quickly LLMs improve with more data—and it holds up in real-world experiments.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved knowledge gaps and open questions

Below is a concise list of limitations, uncertainties, and open questions the paper leaves unresolved, written to enable concrete follow-up work by future researchers.

- Validity beyond the data-limited regime: Extend the theory to model-size-limited and compute-limited regimes; derive analogs of the exponent prediction (e.g., counterparts of ) and characterize regime transitions.

- Rigorous derivation of the horizon threshold: Provide formal concentration bounds and a nonasymptotic analysis justifying under Zipf-distributed tokens, long-range dependencies, topic heterogeneity, and document boundaries.

- Measurement uncertainty and bias in and : Develop principled estimators (with error bars) for and that do not depend on trained models; quantify biases when estimating via and when fitting from empirical co-occurrences.

- Tokenization and preprocessing sensitivity: Systematically measure how and vary with tokenization schemes (e.g., BPE vocab size, WordPiece, unigram LM), text normalization (punctuation, casing), and document segmentation; establish robust protocols that yield stable exponents.

- Generality across domains and languages: Validate the theory on diverse corpora (code, conversational data, books, Common Crawl), multilingual datasets, and morphologically rich languages; assess whether consistently holds.

- Higher-order dependencies: Incorporate multi-token interactions (e.g., conditional mutual information, higher-order cumulants) into the theory; determine when pairwise correlations are insufficient to define and how higher-order structure changes the scaling.

- Broken power-law and cross-over effects: WikiText shows a two-stage decay in ; analyze how cross-overs in induce piecewise scaling in and identify the ranges where exponent changes should occur.

- Master curve and prefactors: Predict the functional form and non-universal prefactors of the collapsed -gram master curve in ; enable quantitative prediction of absolute loss (not only exponents).

- Finite-context corrections: Derive corrections when approaches the maximal context (finite-size effects); provide a scaling function that interpolates between horizon-limited and context-limited regimes.

- Architecture universality: Formally characterize the “horizon-limited” universality class; identify architectural and optimization properties (depth, recurrence, state-space models, CNNs, attention variants) that guarantee fast within-horizon learning and adherence to .

- Beating the horizon-limited exponent: Identify architectural priors (e.g., translational equivariance, hierarchical inductive biases, curriculum learning) or training methods that can improve the within-horizon decay rates and yield exponents larger than .

- Data curation to control exponents: Develop actionable strategies to manipulate and through dataset curation (filtering, balancing, augmentation) and quantify how these changes affect ; connect to prior work on beating power-law scaling via pruning.

- Estimating and entropy tails: Provide methods to estimate and characterize the tail behavior of beyond the initial decay region used in fitting ; assess robustness of when the decay deviates from a pure power law.

- Role of rare tokens and heavy tails: Analyze how Zipf-heavy tails affect covariance estimation, operator-norm scaling, and entropy decay; develop corrections for rare-token regimes (e.g., frequency thresholds, smoothing).

- Document boundaries and non-stationarity: Disentangle intra- and inter-document correlations in ; quantify the impact of topic mixtures and non-stationarity on , , and the predicted scaling.

- Objective and task generalization: Extend the framework beyond autoregressive next-token prediction to masked LMs and seq2seq objectives; define appropriate analogs of and and test whether similar scaling relations hold.

- Optimization and compute sufficiency: Provide diagnostics to verify that experiments are in the data-limited regime (e.g., compute budgets, training steps, batch size, optimizer choices); characterize how gradient noise and optimization dynamics affect .

- Cross-architecture within-horizon decay: Measure (the exponent in ) across architectures, depths, widths, and positional encodings (APE, RoPE, ALiBi, relative positions) and identify design choices that accelerate within-horizon learning.

- Linguistic grounding of exponents: Relate and to known linguistic statistics (dependency length distributions, entropy rates, mutual information decay, syntactic/semantic phenomena) to enable theory-driven predictions from linguistic models.

- Localized correlation peaks: Investigate the observed peak around (TinyStories, WikiText) and model its linguistic origins (phrase structures, sentence rhythms); incorporate such oscillatory features into the scaling description if they systematically recur.

- Prefactor and absolute-loss prediction at scale: Move beyond exponent matching to predict absolute loss curves for large-scale models and contexts typical of production systems (e.g., ), including non-universal constants and finite-size effects.

- Reproducibility and sensitivity analyses: Report comprehensive sensitivity studies (model sizes, hyperparameters, seeds) and provide open-source tools for measuring , , , and performing scaling collapses with uncertainty quantification.

Practical Applications

Below is an overview of practical applications that follow from the paper’s central result: in the data-limited regime, the autoregressive test loss scales as L(P) − H∞ ∝ P−αD with αD = γ/(2β), where:

- γ is the exponent of the decay of next-token conditional entropy with context length n: Hn − H∞ ∝ n−γ.

- β is the exponent of the decay of token–token correlations with lag n: ∥C(n)∥ ∝ n−β.

- The effective, data-dependent prediction horizon grows as n*(P) ∝ P1/(2β), and the minimal data to unlock horizon n scales as P*n ∝ n2β.

- Individual n-gram learning curves collapse under Ln(P) ≈ n−γ * ℓ(P/n2β).

These measurable language statistics can be used to forecast training returns, plan context-window strategy, and prioritize data collection.

Immediate Applications

The items below can be deployed with current tooling and workflows. For each, we note key assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

- Industry (AI/Software)

- Pretraining ROI calculators and scaling planners

- Use case: Before large-scale training, estimate γ and β on candidate corpora, compute αD = γ/(2β), forecast expected loss reductions versus tokens P, and decide whether to allocate budget to more data, larger context, or a different dataset mix.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- “ScaleScope” CLI/SDK that:

- Computes β from token co-occurrence operator norms via randomized SVD on streaming co-occurrence matrices.

- Estimates γ from the small-n decay of Ln using a single sufficiently large, well-trained model.

- Returns αD, n*(P), P*n, and expected L(P) curves with confidence intervals.

- Dashboards integrating dataset analytics with train/compute budgets and projected emissions.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Horizon-limited regime applies and within-horizon learning is fast (as observed for modern LLMs in the paper).

- Corpus is large and representative enough for stable β estimates; tokenization is fixed.

- Stationarity over the context scales of interest (broken power-laws may require local fits).

- Context-window right-sizing and scheduling

- Use case: Match maximum context length T to the unlockable horizon n*(P). Avoid over-provisioning T when n*(P) ≪ T (wasted KV-cache/memory) or under-provisioning when n*(P) ≈ T (bottleneck).

- Workflow:

- At training checkpoints, recompute n*(P) and adjust T or position encodings in subsequent stages.

- Benefits: Reduced memory/latency costs, better throughput, improved compute-efficiency.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Accurate n*(P) estimates from β; support for curriculum-style T schedules in training stack.

- Data procurement targeted to task horizons

- Use case (e.g., legal or code tasks requiring long-range dependencies): If tasks need dependencies at horizon n_task, plan for P ≥ P*n_task ∝ n2β_task to unlock that horizon.

- Workflow:

- Use β to back-calculate minimal P needed to make n_task useful.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable mapping from task performance to required context horizon ranges.

- Dataset curation and mix optimization

- Use case: Choose or blend corpora to increase αD (higher γ and/or lower β), improving data-limited returns.

- Workflow:

- Compute (γ, β) for each candidate dataset.

- Optimize mixture weights to maximize projected αD and minimize P*n for target horizons.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- γ and β are robust across tokenization/domain slices; blending does not introduce severe non-stationarity.

- Training diagnostics and early-stopping using n-gram collapse

- Use case: Monitor Ln(P) curves in rescaled units (nγLn vs. P/n2β). Deviations from collapse can indicate underfitting within-horizon or data/architecture mismatches.

- Workflow:

- Automated “collapse” panels and alerts in training dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Sufficient coverage of n to observe collapse; stable γ and β estimates.

- Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and product design

- Use case: Decide whether adding longer retrieved context is beneficial. If typical effective horizon n*(P) is below the added context span, prioritize more pretraining data or improved within-horizon modeling over longer context.

- Dependencies:

- RAG relevance distributions; RAG introduces non-local dependencies that may change effective β locally.

- On-device/edge model sizing

- Use case: For small-data settings (e.g., on-device personalization), cap T close to n*(P) to save memory and latency without sacrificing utility.

- Dependencies:

- Estimating β from small, possibly non-representative user data requires regularization/sketching.

- Academia (NLP/ML)

- Standardized dataset characterization

- Use case: Report (γ, β) alongside datasets as new quality and difficulty metrics; enable reproducible scaling forecasts and cross-lingual comparisons.

- Workflow: Publish entropy-decay and correlation-decay curves and exponents in dataset releases and benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on measurement protocols (tokenization, counting windows, norms).

- Experimental design and power analysis

- Use case: Use αD and P*n to plan minimal corpus sizes for targeted experimental horizons (syntax, discourse, long narrative).

- Dependencies: Stable measurement of γ, β in subdomains.

- Coursework and pedagogy

- Use case: Teaching labs that measure γ, β, produce collapse plots, and replicate scaling exponents on open corpora.

- Policy & Governance (Public sector, NGOs, corporate governance)

- Transparent scaling forecasts and compute budgeting

- Use case: Require pretraining proposals to publish γ, β, αD, and n*(P)-aligned context plans to justify compute-spend and emissions.

- Dependencies: Standard reporting formats; acceptance of data-limited scaling assumptions by oversight bodies.

- Dataset transparency standards

- Use case: Include entropy/correlation decay reports in public datasets and data-procurement contracts.

- Daily life / SMEs and startups

- Practical model-building decisions with small budgets

- Use case: Estimate whether more data, a longer context window, or a different dataset is the best lever to improve quality for a niche domain.

- Dependencies: Lightweight tools to compute β on small corpora (using sketches or subsampling) and estimate γ from a small trained model.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, engineering, or scaling.

- Industry (AI/Software)

- Online estimation and adaptive training loops

- Vision: Training systems that continuously estimate γ and β, update αD and n*(P), and auto-adjust:

- Context length T (and position encoding).

- Data-mixing schedules and sampling.

- Curriculum over horizons.

- Dependencies: Low-overhead online correlation estimation; robust control policies around non-stationary datasets.

- Data marketplace pricing based on marginal returns

- Vision: Price data by its projected effect on αD and P*n for targeted horizons and domains (e.g., long-form code, scientific text).

- Dependencies: Accepted methodologies for estimating causal contribution of data slices to γ/β; governance frameworks.

- Architectures beyond the “horizon-limited” universality class

- Vision: Develop models (e.g., specialized CNNs/S4/state-space variants) that break current limits and yield larger exponents than γ/(2β) via stronger inductive biases.

- Dependencies: Theory to identify conditions under which within-horizon learning ceases to be fast, or horizon-limited bounds can be surpassed; extensive empirical validation.

- Synthetic/curated data to shape γ and β

- Vision: Generate or select data to increase γ (faster entropy decay with context) and/or decrease β (slower correlation decay), thereby increasing αD.

- Workflows:

- Automatic data curation that removes low-information redundancy or amplifies long-range informative patterns.

- Dependencies: Causally linking curation/generation strategies to shifts in γ and β; avoiding overfitting artifacts.

- Active learning over horizons

- Vision: Query or construct samples that maximally reduce Hn at target n (increasing γ locally) or reveal long-range correlations (affecting β), thereby accelerating horizon unlock.

- Dependencies: Efficient estimators of marginal utility on Hn and ∥C(n)∥ under pool constraints.

- Academia

- Cross-modal generalization and sector-specific studies

- Sectors: Software (code LMs), healthcare/biomed (protein/DNA sequences), speech and multimodal video-text.

- Vision: Test whether similar scaling exponents and collapse hold in other modalities (e.g., symbol sequences, time series), and develop modality-appropriate estimators.

- Dependencies: Domain-specific tokenization and stationary segments; possibly different norms/statistics for correlations.

- Universality-class mapping across architectures

- Vision: Systematically test which model families (Transformers, SSMs, CNNs, hybrids) fall into the horizon-limited class versus those that can surpass it.

- Dependencies: Consistent training regimes and large-scale experiments; agreement on metrics and comparisons.

- New benchmarks annotated with γ and β

- Vision: Benchmarks for long-range understanding with standardized exponents and horizon targets to enable principled scaling studies.

- Policy & Governance

- Standards for scaling-law reporting and sustainability projections

- Vision: Establish norms requiring αD forecasts and n*(P)/T schedules in compute/emission disclosures; guide public-sector AI procurements.

- Dependencies: Community consensus, tooling, and third-party auditability of γ/β/αD estimates.

- Cross-industry & Daily-life impacts

- Better-aligned products for long-context tasks

- Vision: Contract drafting, scientific assistants, or narrative engines that plan data acquisition and training stages around unlocking target horizons, leading to more reliable long-context behavior.

- Dependencies: Translation from horizon targets to task KPIs and evaluation suites.

Notes on assumptions and dependencies common to many applications:

- Horizon-limited regime: The paper’s evidence suggests within-horizon excess losses decay faster than P−γ/(2β) in modern LLMs; if this fails (e.g., shallow nets, kernel methods, poor optimization), forecasts may be optimistic.

- Estimation stability: γ and β estimation assumes adequate corpus size, stable tokenization, and quasi-stationarity over context scales of interest; multi-domain corpora may show broken power laws requiring piecewise modeling.

- Architecture sensitivity: While results matched GPT-2/LLaMA-style models on TinyStories and WikiText, extrapolation to other architectures and training objectives (e.g., RLHF, RAG-heavy pretraining) needs validation.

- Computational overhead: Exact co-occurrence matrices can be large; practical deployments should use streaming/sketching, randomized SVD, or sampling to estimate ∥C(n)∥.

- Task-horizon mapping: Translating downstream performance requirements to target horizons requires domain expertise and empirical calibration.

Glossary

- Absolute positional embeddings (APE): A positional encoding scheme where each token position is assigned a fixed embedding vector, independent of content, used to inject order information into transformers. "GPT-2–style transformers with absolute positional embeddings (Left)"

- Autoregressive loss: The average negative log-likelihood of predicting each next token given all previous tokens, used to train LLMs that generate sequences step by step. "describing the power law reduction of the autoregressive loss in \autoref{eq:autoreg-loss} with an increasing amount of training data"

- Broken power law: A piecewise power-law behavior where different ranges follow distinct exponents, often indicating multiple regimes in the underlying process. "the decay of correlations in WikiText (right panel of~\autoref{fig:two-point-correlations}) is better described as a broken power law with two stages"

- Chinchilla scaling: A compute-optimal training prescription and its observed scaling behavior for LLMs that balances model size and data. "with several subsequent works studying the origins and robustness of Chinchilla scaling"

- Co-occurrence matrix: A matrix counting joint occurrences of token pairs at a given separation, used to quantify dependencies between tokens. "token-token co-occurrence matrix "

- Conditional entropy: The expected uncertainty (in bits or nats) of the next token given a context, measuring how predictable future tokens are given the past. "the next-token conditional entropy at the prediction time horizon bounds from below all the -gram losses"

- Context-free grammars: Formal grammars where production rules apply regardless of surrounding symbols, used to model hierarchical structure in language. "toy models of context-free grammars \cite{cagnetta_how_2024, cagnetta2024towards,allen-zhu_physics_2023,pmlr-v267-garnier-brun25a}"

- Correlation exponent: The exponent β characterizing power-law decay of token-token correlation strength with temporal separation. "the entropy exponent and the correlation exponent are strictly properties of the dataset"

- Curse of dimensionality: The phenomenon where the data requirements grow rapidly with the dimensionality of the features, making learning difficult in high-dimensional spaces. "these methods would suffer from the curse of dimensionality, preventing fast learning with data amount "

- Data-dependent prediction time horizon: The maximum context length a model can effectively exploit given the available training data. "Data-dependent prediction time horizon. Given the number of training tokens , the data-dependent prediction time horizon can be defined as the maximal context window size that the model can beneficially leverage"

- Data-limited regime: A scaling regime where performance is primarily constrained by the amount of training data rather than model size or compute. "In this work, we focus on the data-limited regime"

- Entropy exponent: The exponent γ characterizing how the next-token conditional entropy decreases as context length grows. "the entropy exponent and the correlation exponent are strictly properties of the dataset"

- Frobenius norm: A matrix norm equal to the square root of the sum of squared entries, used here to summarize correlation strength. "using the Frobenius norm yields the same decay"

- GPT-2–style transformer: A transformer architecture similar to GPT-2, used as a baseline for autoregressive language modeling experiments. "the highly diverse -gram losses (\autoref{eq:ngram-loss}) of a GPT-2–style transformer trained from scratch on -tokens of the TinyStories dataset"

- Horizon-limited regime: A regime where excess loss is dominated by the finite effective context that can be exploited given the data size. "\autoref{eq:ar-scaling} captures a horizon-limited regime in which the dominant contribution to the excess test loss comes from the fact that, at dataset size , only statistical token dependencies up to a maximal time separation are available to aid prediction"

- Kernel methods: Learning methods using fixed feature maps or kernels, where generalization is analyzed via spectral properties, contrasting with feature-learning in deep models. "Existing theoretical approaches to deriving loss learning curves have predominantly focused on kernel methods"

- LLaMA-style transformer: A transformer architecture inspired by LLaMA models, used to test scaling predictions across architectures. "and LLaMA-style transformers (Center Right)"

- Marginal over length-n sequences: The probability distribution over sequences of a fixed length n obtained by marginalizing the full sequence distribution. "write for its marginal over length- sequences"

- Negative log-likelihood: A loss function equal to the negative log of the predicted probability of observed data, minimized during training. "training proceeds by gradient descent on the negative log-likelihood"

- Neural scaling laws: Empirical power-law relationships between model performance and resources like data, model size, or compute. "following approximate power laws known as Neural Scaling Laws"

- Operator norm: The largest singular value of a matrix, used to quantify the strongest correlation signal in token co-occurrence. "We extract a scalar summary of the correlation strength by taking the operator norm $\| C(n) \|_{\mathrm{op}$"

- Phase structure: The organization of distinct regimes (phases) in model or data behavior, often with different scaling properties. "and \cite{paquette2024phases} derive phase structure and compute-optimal tradeoffs"

- Phase transitions: Sharp changes in system behavior characterized by critical points and exponents, analogous to regime shifts in learning curves. "In physics, phase transitions are characterized by universality classes"

- Power law: A functional relationship where a quantity varies as a fixed power of another, often indicating scale-free behavior. "empirically observes power-law decays in each"

- Random feature model: A model where features are randomly generated and fixed, used to analyze learning behavior in simplified settings. "\cite{maloney2022solvable} solve a joint generative and random feature model"

- Rotary positional embeddings (RoPE): A positional encoding technique that rotates token representations in a way that supports relative position information. "GPT-2–style transformers with rotary positional embeddings (RoPE, Center Left)"

- Scaling collapse: The phenomenon where differently parameterized curves align onto a single master curve after appropriate rescaling, indicating universal behavior. "in terms of {\it scaling collapse} of families of loss curves with different fixed context lengths"

- Signal-to-noise argument: An analysis comparing the strength of a detectable signal against statistical noise to determine the data threshold for reliable measurement. "Then, a signal-to-noise argument where the signal is $\| C(n)\|_{\mathrm{op}$ and the noise is the difference with the empirical covariance matrix $\| \widehat{C}_P(n)-C(n)\|_{\mathrm{op}\,{=}\,O(P^{-1/2})$ gives the threshold"

- Spectral properties: Characteristics of the eigenvalue or singular value spectrum of a kernel or feature map, used to predict learning behavior in kernel methods. "test loss can be predicted from the spectral properties of a {\it fixed} feature map or kernel"

- Top singular value: The largest singular value of a matrix, indicating the strongest mode in the data correlations. "and take the top singular value $\| C(n)\|_{\mathrm{op}$ as a measure of the strongest signal in the matrix"

- Translational equivariance: A property of models (e.g., CNNs) whose outputs shift consistently with input translations, aiding learning in structured data. "CNNs can actually perform better thanks to translational equivariance"

- Two-point correlation function: A function measuring statistical dependence between pairs of tokens separated by a given lag. "the decay of the two-point correlation function, defined as the norm of the token-token co-occurrence matrix"

- Universality classes: Groups of systems that share the same critical exponents and scaling behavior despite microscopic differences. "In physics, phase transitions are characterized by universality classes: large sets of systems that share the same critical exponents"

- Zipf-distributed tokens: Tokens whose frequency follows Zipf’s law, where the frequency is inversely proportional to rank, common in natural language. "time-dependent scaling exponents for linear bigram models trained on Zipf-distributed tokens"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.