Value-Based Pre-Training with Downstream Feedback

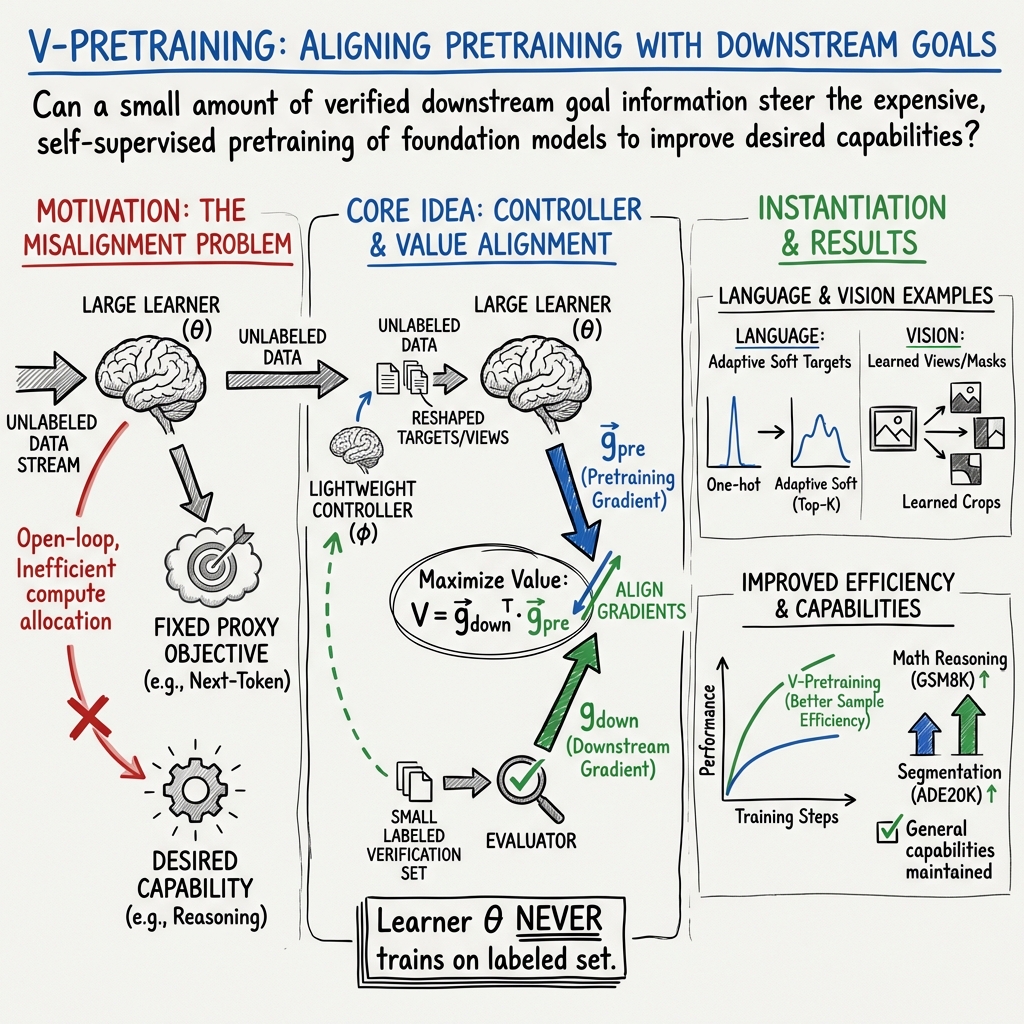

Abstract: Can a small amount of verified goal information steer the expensive self-supervised pretraining of foundation models? Standard pretraining optimizes a fixed proxy objective (e.g., next-token prediction), which can misallocate compute away from downstream capabilities of interest. We introduce V-Pretraining: a value-based, modality-agnostic method for controlled continued pretraining in which a lightweight task designer reshapes the pretraining task to maximize the value of each gradient step. For example, consider self-supervised learning (SSL) with sample augmentation. The V-Pretraining task designer selects pretraining tasks (e.g., augmentations) for which the pretraining loss gradient is aligned with a gradient computed over a downstream task (e.g., image segmentation). This helps steer pretraining towards relevant downstream capabilities. Notably, the pretrained model is never updated on downstream task labels; they are used only to shape the pretraining task. Under matched learner update budgets, V-Pretraining of 0.5B--7B LLMs improves reasoning (GSM8K test Pass@1) by up to 18% relative over standard next-token prediction using only 12% of GSM8K training examples as feedback. In vision SSL, we improve the state-of-the-art results on ADE20K by up to 1.07 mIoU and reduce NYUv2 RMSE while improving ImageNet linear accuracy, and we provide pilot evidence of improved token efficiency in continued pretraining.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A simple guide to “Value-Based Pre-Training with Downstream Feedback”

What is this paper about?

This paper asks a big question: can we use a small amount of trusted information about our goals to guide the way we train huge AI models from scratch? Today, these models learn in a very “blind” way—by predicting the next word in text or filling in missing parts of images—without knowing what skills people actually want (like math reasoning or detailed image understanding). The authors propose a new method, called V-Pretraining, that gently steers this early training toward the skills we care about, using a tiny bit of checked feedback, and without directly training on those labels.

What were the goals or questions?

The researchers wanted to:

- Find a way to add “goal awareness” to pretraining, so the model’s practice focuses on useful skills.

- Do this in a way that works for different kinds of data (language and images).

- Keep the main training budget fixed, and use only small amounts of labeled feedback.

- Avoid directly training the big model on the feedback labels, to preserve the benefits of self-supervised learning.

- Show that this steering improves results and does not harm general abilities.

How does the method work?

Think of training a model like training an athlete:

- The athlete (the “learner”) practices using drills (predicting the next word, reconstructing parts of an image).

- Normally, these drills are chosen at the start and never change, even if they don’t help with winning real matches (solving math problems or segmenting images).

- The authors add a small “coach” (the “task designer”) who watches a few real matches and then adjusts the practice drills so each training step moves the athlete closer to winning.

In everyday terms:

- Pretraining is practice: the model learns by predicting something simple (like the next word) using tons of unlabeled data.

- Downstream tasks are real matches: tasks we care about, like solving math word problems (GSM8K) or labeling every object in an image (ADE20K).

- The coach does not change the athlete using match labels directly. Instead, the coach tweaks the practice itself so it naturally helps with match performance.

A core idea is “gradient alignment,” which you can imagine like arrows showing the direction to improve. One arrow comes from practice (the usual training step), and one arrow comes from the goal task (computed using a small labeled set). If the arrows point in the same direction, the practice step should help the real goal. The coach tries to choose practice targets or views that make these arrows line up.

Here’s how it looks in two types of data:

- Language (text): Instead of training with a “one correct next word” label, the coach creates a soft target over a few likely next words. These soft labels are adjusted so practice steps better support reasoning skills.

- Vision (images): Instead of using fixed image “augmentations” (like random crops), the coach chooses smart, instance-specific views of each image. These views make the model learn features that help with dense tasks (like segmentation or depth estimation).

In short, the learner keeps doing normal self-supervised training, but the coach shapes what it sees and what it aims for in each step.

A simple view of the algorithm:

- For each training step, the learner takes an unlabeled batch (normal practice).

- The coach designs the practice target or image view for that batch.

- The system measures how much this practice step would help the goal task (using the “arrow alignment” idea).

- The coach updates itself to make future practice steps more helpful.

- The learner then updates on the shaped practice step.

The paper also provides math showing that, under reasonable conditions, making the arrows align increases the chance that each step helps the goal task.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

The authors tested V-Pretraining on both language and vision and found consistent, meaningful improvements, even though the learner was never trained directly on the downstream labels.

Key takeaways:

- Language reasoning improved: Continued pretraining of 0.5B–7B LLMs on math text, guided by only about 12% of GSM8K training examples, improved test accuracy by up to about 18% relative (and about 2–14% in concrete runs). This means the model got better at math reasoning while still learning mostly from unlabeled text.

- Vision got more precise: On image tasks, they improved segmentation scores (ADE20K mIoU up to +1.07) and reduced depth estimation error (NYUv2 RMSE reduced), while keeping or slightly improving general image recognition (ImageNet linear accuracy).

- No loss of generality: The improvements did not cause the model to forget general skills. Tests on other benchmarks (like MMLU for language and Oxford/Paris instance retrieval for vision) were maintained or improved.

- More efficient use of tokens: The value-based approach reached certain accuracy levels with fewer training steps, suggesting better “value per token.”

- Small overhead: The steering added a modest compute cost (e.g., ~16% lower throughput, ~19% longer step time in one language setup), and the “value update” itself took only a small fraction of GPU time.

These results matter because they show we can make large-scale pretraining smarter and more goal-directed without sacrificing the strengths of self-supervised learning or requiring massive amounts of labeled data.

What is the impact or why is this important?

As training bigger models and collecting more data gets increasingly expensive, we need ways to use compute more effectively. This method:

- Steers the model during the most expensive phase (pretraining), not just after, which can save time and improve results.

- Uses only small amounts of verified feedback as “lightweight guidance,” preserving the scalability of self-supervised learning.

- Works across different types of data and tasks (language and vision).

- Offers a practical path toward “weak-to-strong” supervision: small, trustworthy signals can help a large model develop strong capabilities.

- Allows multi-goal control: by changing the feedback weights, you can trade off improvements in different tasks (e.g., segmentation vs. depth).

- Opens doors to future oversight: in the long run, feedback could come from human preferences, pass/fail checks, or tool success, further aligning models with human goals.

In short, V-Pretraining shows that a little smart coaching during practice can make a big difference. It could help future AI models learn the right skills faster, with less waste, and in a way that’s easier to align with what people actually want.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, framed to guide actionable next steps for future research.

- Long-horizon efficacy beyond one-step alignment: The method optimizes a one-step gradient alignment value; there is no analysis or empirical study of how well this proxy predicts multi-step or end-of-run downstream improvement across long pretraining horizons.

- Theoretical guarantees under realistic non-convex training: Guarantees rely on L-smoothness and small step sizes with only first-order approximations; there is no bound on cumulative downstream improvement, no analysis of estimator variance, and no robustness guarantees under non-convex dynamics or larger learning rates.

- Stability and convergence of the bi-level loop: The paper reports an early transient dip and uses a burn-in schedule, but does not analyze convergence properties, oscillation modes, or provide principled schedules/regularizers for stable designer–learner co-training.

- Sensitivity to the subset of parameters used for the value signal: The value function is computed on a restricted parameter subset (e.g., adapters/last layers), yet there is no systematic study of which subsets work best, how sensitive performance is to this choice, or how to choose subsets adaptively.

- Robustness to noisy, sparse, or adversarial feedback: All evaluators are clean, differentiable supervised tasks; the method’s behavior with label noise, sparse signals, or adversarially corrupted feedback remains untested.

- Non-differentiable feedback channels: Integration with pass/fail metrics, preferences, tool success rates, or other non-differentiable evaluators is proposed as future work but not instantiated; concrete estimators (e.g., learned critics, REINFORCE-style estimators) and their stability–variance tradeoffs remain open.

- Active selection of evaluator batches: The evaluator set is randomly sampled; there is no active selection strategy to maximize the informativeness of the downstream gradient (e.g., core-set selection, uncertainty-driven sampling, or curriculum over evaluator examples).

- Overfitting to a small evaluator set: With 1–3k labeled examples driving the designer, there is a risk of overfitting the designer (and indirectly the learner) to the evaluator distribution; no explicit held-out evaluator monitoring, early-stopping criteria for the designer, or regularization strategies are provided.

- Distribution shift between evaluator and deployment tasks: While some OOD checks are included, there is no systematic evaluation of how value-based steering behaves when evaluator data are substantially misaligned with target deployment distributions.

- Multi-objective control beyond weighted sums: The approach linearly combines downstream gradients with fixed weights; more principled Pareto-aware methods (e.g., MGDA, hypervolume maximization, constrained updates) and dynamic weighting policies are not explored.

- Reward hacking and proxy gaming risks: The designer could inflate gradient alignment without real downstream gains (e.g., by increasing gradient magnitudes or exploiting shortcuts); there is no adversarial testing, norm/curvature control, or auditing protocol to detect such behavior.

- Privacy and indirect label leakage: Although the learner is not directly updated on downstream labels, labels influence the learner via designer-shaped targets; no formal privacy or leakage analysis (e.g., membership inference, DP guarantees) is provided.

- Compute and systems scalability: Overhead is reported for a single-GPU language setting; there is no characterization of cost/throughput on large distributed runs, pipeline/model parallelism, trillion-token regimes, or the impact of frequent Hessian–vector products on memory and throughput at scale.

- Update frequency and staleness: The method updates the designer online, but there is no analysis of how often to recompute downstream gradients, the effects of stale value signals, or the trade-off between frequent vs. amortized designer updates.

- From-scratch vs. continued pretraining: All experiments are continued pretraining; it remains unknown whether value-based steering helps or hurts when training from scratch and at what stages of optimization it is most beneficial.

- Breadth of domains and tasks: Language experiments focus on math reasoning; vision uses dense prediction and ImageNet linear evaluation. Generality to instruction following, coding, multilingual/multimodal tasks, speech, video, and tool use is untested.

- Interaction with standard post-training: There is no rigorous comparison, at matched compute and label budgets, of V-Pretraining versus (or combined with) SFT/RLHF/DPO; the cost–benefit break-even versus conventional post-training remains unclear.

- Cost-effectiveness relative to fine-tuning on the same labels: For a fixed label budget and compute envelope, it is not shown whether directing pretraining yields greater downstream gains than simply using the labels for supervised fine-tuning.

- Token/sample efficiency at scale: The token-efficiency result is a small pilot; there is no large-scale validation across orders of magnitude in tokens/models, different unlabeled mixtures, or robustness to curriculum/data refresh.

- Language target design details: The top-K soft target mechanism lacks a study of K, candidate selection strategy, calibration effects, impact on rare tokens/long-tail, changes to perplexity, and trade-offs between softening magnitude and downstream gains.

- Vision view generator behavior: The learned augmentation module may risk degenerate or collapsing transformations; constraints, diagnostics, and interpretability of learned views, as well as transferability of learned view policies across datasets, are not evaluated.

- Generalization and safety side effects: While MMLU/OMEGA and retrieval are measured, broader assessments of truthfulness, calibration, toxicity, bias/fairness, and robustness are absent; small-model regressions (e.g., 0.5B on MMLU) indicate possible trade-offs needing deeper analysis.

- Variance and reliability of the value estimator: There is no empirical characterization of the variance of g_downT g_pre across batches, its signal-to-noise ratio as training progresses, or methods (e.g., averaging, control variates) to stabilize the meta-signal.

- Correlation assumptions in unbiasedness lemma: The unbiasedness claim requires independent batches for g_pre and g_down; the impact of correlated sampling (common in high-throughput pipelines) and of batch/loss scaling choices is not studied.

- Designer capacity and architecture: The paper does not ablate designer capacity, regularization, or architecture to understand overfitting risk, computational footprint, and the minimal complexity needed for effective control.

- Scheduling and curriculum for the designer: No principled schedule is provided for when and how strongly to apply value-based steering (e.g., burn-in length, annealing, alternating phases, or curriculum over tasks/objectives).

- Layer-wise or representation-space targeting: The value signal is defined in parameter space; there is no exploration of representation-space alignment (e.g., Jacobian–feature alignment), layer-wise weighting, or spectral/curvature-aware value functions.

- Alternative value proxies: Only dot-product alignment is considered; other first-order surrogates (e.g., cosine-only, Fisher-weighted alignment, trust-region constraints, curvature-aware alignment) are unexplored.

- Data selection and mixture control: The unlabeled stream is fixed; integrating data selection/curriculum (e.g., selecting unlabeled examples with high predicted value) with target/view shaping is not investigated.

- Security and poisoning resilience: There is no evaluation of robustness to evaluator poisoning or targeted manipulations that could steer the designer toward harmful behaviors.

- Implementation portability: Practicalities of Hessian–vector products, mixed precision, compiler/autodiff support, and numerical stability across frameworks (e.g., PyTorch/XLA/JAX) are not discussed, leaving engineering risks unassessed.

Practical Applications

Below is a concise analysis of practical, real‑world applications enabled by the paper’s V‑Pretraining method. Each item highlights sectors, concrete use cases, potential tools/workflows/products, and feasibility assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

These can be deployed now with modest engineering effort, using differentiable downstream evaluators and continued pretraining on existing models.

- Healthcare (medical imaging)

- Application: Improve segmentation and depth‑related perception (e.g., organ/tumor segmentation, anatomical landmark detection) by steering self‑supervised vision encoders with small labeled sets from target tasks.

- Tools/workflows/products: “Learned‑view” augmenter module integrated into MAE/DINOv3 pipelines; small curated segmentation/dev sets; multi‑objective weighting UI to balance tasks (e.g., segmentation vs. depth); monitoring of mIoU/RMSE during continued pretraining.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable losses (cross‑entropy, Dice, RMSE) available for evaluators; de‑identified labeled examples; regulatory compliance (HIPAA/GDPR); access to unlabeled clinical images; careful bias auditing of the small evaluator set.

- Robotics and Autonomous Systems (perception stack)

- Application: Increase dense prediction quality (segmentation, depth, layout) for SLAM and scene understanding by learning instance‑wise augmentations that align SSL gradients with downstream perception gradients.

- Tools/workflows/products: DINO/MAE backbones with a learned view generator; Pareto controller to trade off segmentation vs. depth (gradient mixing weights α); automated value‑per‑token dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable evaluators (e.g., dense regression/classification heads); representative small labeled frames; stable gradient estimates; availability of large unlabeled driving/robotics video streams.

- Software/AI Platforms (domain‑specialized LMs)

- Application: Compute‑efficient continued pretraining of LLMs toward domain reasoning (e.g., math, compliance QA, basic financial QA) using small labeled evaluators to generate adaptive top‑K soft targets.

- Tools/workflows/products: “Task designer” head producing per‑token soft targets; value server computing g_down on a small, curated dev set; integration with Megatron‑LM/DeepSpeed/PEFT for parameter‑subset gradient alignment; burn‑in and step‑size schedules.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable downstream loss (e.g., cross‑entropy on labeled answers); modestly sized, representative evaluator (1–3k examples shown to be effective); access to model gradients; minor throughput overhead acceptance.

- Education (tutoring and assessment)

- Application: Steer small‑to‑mid‑sized LMs toward mathematical reasoning or structured problem‑solving for tutoring apps, improving sample/token efficiency with a small, vetted problem set.

- Tools/workflows/products: Curated evaluator sets (e.g., school curriculum problem banks with answers); adaptive soft‑target generation; token‑efficiency monitors for cost control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable evaluation (answer supervision); care to avoid data contamination; maintain generality by not fine‑tuning on evaluator labels.

- Industrial Inspection and Manufacturing (vision QA)

- Application: Improve defect detection and segmentation in low‑label regimes by replacing fixed augmentations with learned, instance‑wise views aligned to a small labeled QA set.

- Tools/workflows/products: Augmentation controller module integrated with self‑supervised encoders; small annotated defect masks/regions; multi‑objective controls (e.g., contrast vs. structure).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable segmentation/classification losses; access to high‑volume unlabeled imagery; risk management for false negatives.

- Public Sector and Policy (compute efficiency targets)

- Application: Reduce unlabeled tokens/images needed to reach target accuracy for mission‑specific capabilities (e.g., disaster mapping segmentation, public health triage classifiers) by increasing value‑per‑step in continued pretraining.

- Tools/workflows/products: Token‑efficiency dashboards; standardized evaluator sets for public‑interest tasks; reporting on value‑per‑token as a sustainability metric.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable evaluators; a small, high‑quality labeled dev set representative of policy‐relevant tasks; transparency about trade‑offs and bias in evaluators.

- Information Retrieval and Document Understanding (finance/legal)

- Application: Improve representations for retrieval and structured extraction (e.g., contract clauses, regulatory documents) while preserving generalization by steering encoders with small labeled evaluators.

- Tools/workflows/products: Learned‑view SSL for vision (document images) and soft‑target shaping for LMs (answerable QA sets); linear‑probe validation; Pareto controls for precision/recall.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable evaluator tasks (classification/extraction supervision); tight governance over evaluator construction to avoid embedding institutional bias.

- MLOps/Research (representation diagnostics and control)

- Application: Rapidly probe which augmentations/targets increase downstream value per step; run controlled ablations with gradient‑alignment value signals; maintain Pareto frontiers for multi‑objective goals.

- Tools/workflows/products: “Value‑alignment monitor” (g_down * g_pre) for selected parameter subsets; HVP utilities; experiment tracking with α‑sweeps for task tradeoffs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Autograd support for Hessian‑vector products; independence of batches for unbiased value estimates; acceptance of small runtime overhead.

Long‑Term Applications

These require additional research, scaling, or new value estimators to handle non‑differentiable feedback, online oversight, or foundation‑scale training from scratch.

- Software Engineering and Tool Use (non‑differentiable evaluators)

- Application: Steer pretraining with unit‑test pass/fail, compiler success, or tool‑chain execution outcomes for code LMs.

- Tools/workflows/products: Learned value estimators or REINFORCE‑style surrogates for non‑differentiable signals; “test‑driven pretraining” pipelines; caching of test outcomes and credit assignment across steps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable proxy gradients from non‑diff signals; compute budget for repeated executions; careful credit assignment to avoid reward hacking.

- Human Preference and Safety Alignment During Pretraining

- Application: Incorporate preference judgments, red‑team findings, or policy constraints as value signals to shape representations toward safer outputs earlier in training.

- Tools/workflows/products: Small preference models (PMs) to provide differentiable surrogates; scalable oversight protocols; safety‑oriented “value gradients” APIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Trustworthy and representative human signals; bias and fairness audits; mechanisms to prevent capability over‑optimization for narrow evaluators.

- Foundation‑Scale Training and Dynamic Curricula

- Application: Use V‑Pretraining throughout full training runs (not only continued pretraining) with dynamic data mixtures, curriculum schedules, and value‑based task selection at scale.

- Tools/workflows/products: Data schedulers that adapt mixtures from value signals; low‑overhead HVP acceleration; large‑scale orchestration for multi‑task gradient alignment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable training under long horizons; engineering to manage optimizer state interactions and meta‑updates; compute cost/benefit at foundation scale.

- Cross‑Modal and Multimodal Steering (audio, video, language‑vision)

- Application: Extend task designers to shape targets/views across modalities (e.g., audio‑visual pretraining for robotics, AR/VR scene understanding, medical multi‑modal data).

- Tools/workflows/products: Modality‑specific augmenters (e.g., temporal crops/masks for video); cross‑modal evaluators (e.g., text‑to‑segmentation alignment); Pareto controllers for multimodal objectives.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Differentiable multi‑modal evaluators; synchronization of unlabeled streams; robust cross‑modal gradient alignment.

- Privacy‑Preserving or Federated Value Feedback

- Application: Compute downstream gradients on‑prem or on‑device and aggregate securely to steer pretraining without exposing raw data (healthcare, finance).

- Tools/workflows/products: Federated gradient aggregation; secure enclaves/SMPC; differential privacy on evaluator gradients.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Communication‑efficient value updates; privacy guarantees; tolerant performance under DP noise.

- Marketplace and Standardization of “Value Data”

- Application: Curate and exchange small, high‑quality evaluator sets (and associated differentiable loss definitions) as a new asset class to steer general models toward specific capabilities.

- Tools/workflows/products: Reproducible value‑set repositories; standardized “value gradient” APIs; benchmarking suites for value‑per‑token.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensing and provenance frameworks; mitigation of overfitting to public evaluators; governance to avoid narrow optimization and societal harms.

- Hardware/Systems Co‑Design for Meta‑Gradients

- Application: Specialized kernels or accelerators for Hessian‑vector products and gradient‑alignment computation to minimize overhead at scale.

- Tools/workflows/products: Autograd enhancements; memory‑efficient HVP; compiler passes for selective parameter‑subset alignment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor support; demonstrated ROI at scale; integration with major training stacks.

- Continual/Online Learning with Real‑Time Oversight

- Application: Stream value signals from live metrics (tool success rates, user feedback) to steer ongoing pretraining of deployed models.

- Tools/workflows/products: Online value estimators; drift detection and reweighting of objectives; safeguards against feedback loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robustness to non‑stationary evaluators; latency‑aware meta‑updates; guardrails against self‑reinforcing biases.

- Policy and Sustainability Frameworks

- Application: Use value‑per‑token as a procurement and sustainability metric; require disclosure of steering objectives and evaluator composition in high‑compute training.

- Tools/workflows/products: Reporting standards for value‑aligned pretraining; third‑party audits of evaluator bias and environmental gains.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consensus on metrics; regulatory adoption; methods to ensure transparency without leaking sensitive evaluators.

Notes on feasibility and risks across applications:

- Representativeness of the small evaluator set is crucial; misalignment can optimize the wrong capability. Multi‑objective and periodic re‑validation mitigate this.

- Tasks must currently admit differentiable evaluators for immediate use; non‑differentiable signals require additional research (or surrogate losses).

- Compute overhead is modest but real; selective parameter subsets and efficient HVPs help. Careful scheduling (e.g., burn‑in) stabilizes training.

- For smaller models, monitor generalization to avoid over‑specialization; the paper observed slight regressions on some out‑of‑family benchmarks at the smallest scale.

Glossary

- ADE20K: A widely used semantic segmentation dataset of diverse scenes. "we improve the state-of-the-art results on ADE20K by up to 1.07 mIoU"

- augmentation pipeline: The set of data transformations used to generate training views in self-supervised learning. "a fixed augmentation pipeline in vision"

- bilevel optimization: An optimization setup with nested objectives, where the inner problem’s solution is used by an outer problem. "it is a bilevel problem that would require differentiating through long pretraining trajectories"

- cosine loss: A loss that minimizes the cosine distance (1 − cosine similarity) between vectors. "and the predictor matches latent targets under a regression or cosine loss"

- cross-entropy (CE) loss: A standard classification loss comparing predicted distributions to target distributions. "With cross-entropy (CE) loss"

- DINOv3: A state-of-the-art self-supervised vision training method/backbone for ViTs. "Our baseline starts from DINOv3 pretrained ViT backbones"

- downstream feedback: Supervision signals from labeled downstream tasks used to steer pretraining. "We evaluate whether small, verifiable downstream feedback can steer continued pretraining"

- downstream gradient: The gradient of a downstream task loss with respect to the learner’s parameters. "and define the downstream gradient"

- GSM8K: A benchmark of grade-school math word problems for evaluating reasoning. "using only $12$\% of GSM8K training examples as feedback"

- Hessian-vector product: The product of a loss’s Hessian with a vector, enabling efficient meta-gradient computation. "a Hessian vector product that can be computed by automatic differentiation"

- ImageNet linear accuracy: Accuracy of a linear classifier trained on frozen ImageNet features, used to assess representation quality. "reduce NYUv2 RMSE while improving ImageNet linear accuracy"

- influence-style first-order estimate: A gradient-based approximation that estimates how a training step affects downstream loss. "by defining the value of a pretraining step via an influence-style first-order estimate"

- InfoNCE: A contrastive loss encouraging matched positives and separated negatives. "loss (cross-entropy, regression, cosine, InfoNCE, etc.)"

- JEPA (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture): A paradigm that predicts target representations in a joint-embedding space instead of reconstructing inputs. "JEPA-style prediction"

- joint-embedding: Learning by aligning embeddings of correlated views without reconstructing raw inputs. "contrastive/joint-embedding objectives"

- masked autoencoding (MAE): A self-supervised method that reconstructs masked portions of the input. "For masked autoencoding"

- mean Average Precision (mAP): A retrieval metric averaging precision over recall thresholds. "improves mAP on the Medium protocol"

- mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU): A segmentation metric averaging the overlap between predicted and true regions across classes. "We report ADE20K mIoU, NYUv2 RMSE, ImageNet linear accuracy"

- NYUv2: An indoor scene dataset with depth and segmentation annotations used for dense prediction tasks. "reduce NYUv2 RMSE"

- Pareto frontier: The set of optimal trade-offs where improving one objective worsens another in multi-objective optimization. "We observe a Pareto frontier"

- Pass@1: The probability that a single generated attempt solves the task (top-1 success rate). "GSM8K test Pass@1"

- preference optimization: Methods that align models by optimizing against human preference signals. "supervised fine-tuning or preference optimization"

- stop-gradient: An operation that prevents gradients from flowing through a tensor during backpropagation. "\tau(x_t) = \mathrm{stopgrad}\big(f_{\theta'}(x_t)\big)"

- top-K soft targets: Target distributions spread over the model’s top-K candidates instead of a one-hot label. "adaptive soft targets supported on the learner's top- candidates"

- value function: A scalar measure used to score a pretraining step by its predicted downstream improvement. "We therefore define the value function"

- weak-to-strong supervision: Using small or weak supervision signals to elicit stronger capabilities in large models. "indirect downstream feedback can act as a scalable form of weak-to-strong supervision during pretraining"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.