The Illusion of Insight in Reasoning Models

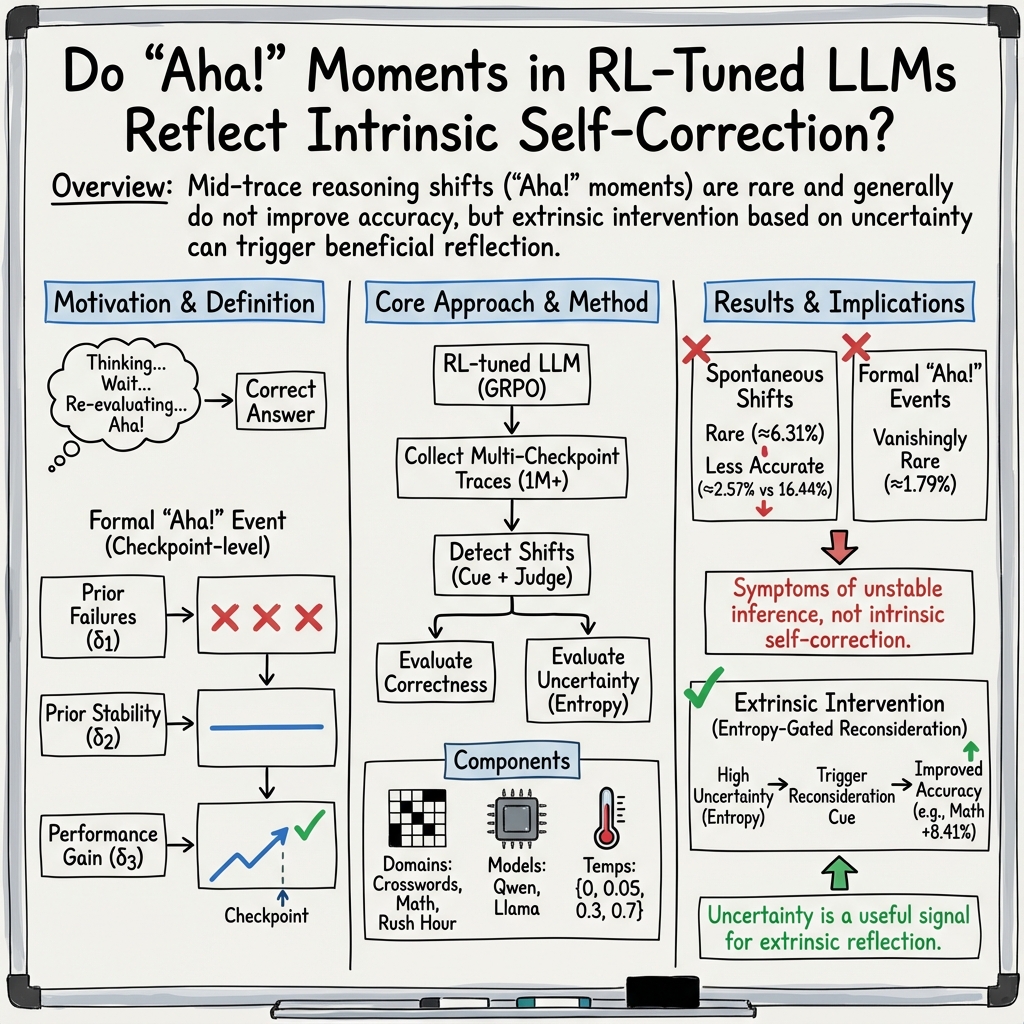

Abstract: Do reasoning models have "Aha!" moments? Prior work suggests that models like DeepSeek-R1-Zero undergo sudden mid-trace realizations that lead to accurate outputs, implying an intrinsic capacity for self-correction. Yet, it remains unclear whether such intrinsic shifts in reasoning strategy actually improve performance. Here, we study mid-reasoning shifts and instrument training runs to detect them. Our analysis spans 1M+ reasoning traces, hundreds of training checkpoints, three reasoning domains, and multiple decoding temperatures and model architectures. We find that reasoning shifts are rare, do not become more frequent with training, and seldom improve accuracy, indicating that they do not correspond to prior perceptions of model insight. However, their effect varies with model uncertainty. Building on this finding, we show that artificially triggering extrinsic shifts under high entropy reliably improves accuracy. Our results show that mid-reasoning shifts are symptoms of unstable inference behavior rather than an intrinsic mechanism for self-correction.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper asks a simple question: do AI “reasoning” models really have “Aha!” moments, like people do when they suddenly figure something out? The authors look closely at the moments when a model changes its approach mid-answer (for example, it writes “Wait… let’s re‑evaluate”) to see if these shifts actually help it get the right answer more often.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The paper focuses on three easy-to-understand questions:

- Do mid‑answer shifts (“Aha!” moments) make the model more accurate?

- Does the effect of these shifts change as the model gets more training or when we make its answers more or less random?

- Are these shifts more helpful when the model is uncertain, and can we use that uncertainty to trigger helpful reconsideration?

How did they study it?

To answer these questions, the authors did a large, careful study:

The tasks (what the models tried to solve)

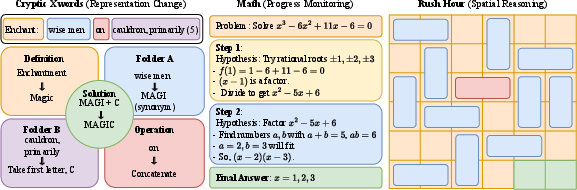

They tested the models in three different areas:

- Cryptic crosswords: tricky word puzzles where you often need to “re‑parse” clues in a new way.

- Math problems (MATH-500): multi-step problems where careful step-by-step reasoning matters.

- Rush Hour puzzles: sliding-block puzzles that require planning moves to free a car.

These cover different kinds of thinking: changing representations (crosswords), step-by-step logic (math), and spatial planning (Rush Hour).

The models and training

They fine-tuned two families of LLMs (Qwen2.5 and Llama) using a reward-based training method called GRPO. In simple terms, GRPO is like giving the model points for better reasoning and comparing groups of its answers to guide improvement. They saved copies (“checkpoints”) of the models during training and tested them repeatedly to see how behavior changed over time.

Key setup details:

- Over 1 million reasoning traces (the “chains of thought” the models wrote).

- Many checkpoints across training.

- Multiple randomness settings (“decoding temperatures”).

- Different model sizes and architectures.

Detecting “Aha!” moments

They looked for mid-answer shifts—places where the model clearly changes strategy, often marked by cues like “Wait…” or “Let’s rethink this.” They used a strong evaluator (another AI judge) with a fixed rubric to label:

- If a shift happened,

- Whether the final answer was correct,

- Whether the shift seemed to help.

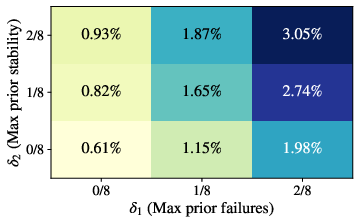

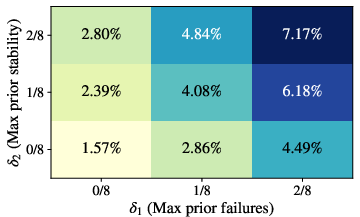

They also defined a stricter, formal version of an “Aha!” moment with three conditions:

- The problem was mostly unsolved by earlier versions of the model,

- Those earlier versions didn’t show many shifts,

- At the current checkpoint, answers with a shift were clearly more accurate than average.

This formal definition is meant to filter out fake or noisy “Aha!” moments.

Measuring uncertainty and trying interventions

They measured the model’s uncertainty using token-level entropy. In everyday terms:

- Decoding temperature: controls how adventurous or random the model’s choices are. Low temperature = cautious; high temperature = more exploratory.

- Entropy: a score for how unsure the model seems at each step. High entropy means many different next words look similarly likely; low entropy means the model is more certain.

With this uncertainty measure, they tested a simple intervention: when the model seemed uncertain, add a short reconsideration cue like “Wait, something is not right, let’s think this through step by step,” and then have it answer again. They compared before vs. after to see if this helped.

What did they find?

The main results are clear and practical:

- Shifts are rare and usually don’t help.

- Across tasks and models, only about 6 out of 100 answers showed a mid‑answer shift.

- When shifts happened, those answers were less accurate than ones without shifts.

- The stricter, formal “Aha!” moments (the ones that truly look like sudden insight) were extremely rare.

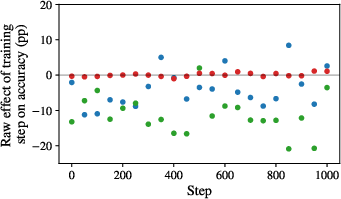

- Training more didn’t make shifts helpful.

- Watching the model across training checkpoints, the authors didn’t see a reliable flip where shifts became good later on.

- In other words, “Aha!”-style self-correction didn’t emerge steadily with training.

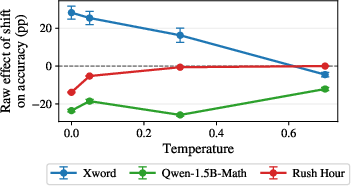

- Temperature (randomness) changes the picture, but not in a simple “more is better” way.

- At lower temperatures on crosswords, shifts sometimes aligned with helpful corrections.

- In math, shifts were consistently harmful across temperatures (though slightly less harmful at higher temperatures).

- In Rush Hour, shifts didn’t make much difference because accuracy was near zero overall.

- “Spontaneous” shifts aren’t reliably helpful under uncertainty—but “triggered” reconsideration can be.

- Just being uncertain (high entropy) didn’t make the model’s own mid‑answer pivots more helpful.

- However, if you explicitly prompt the model to reconsider when it seems uncertain, accuracy improves—especially in math.

- On MATH-500, this entropy‑gated reconsideration cue boosted accuracy by about +8.41 percentage points. Gains were smaller but present in crosswords; Rush Hour stayed very hard.

Overall conclusion: those “Wait… let’s re‑evaluate” moments mostly reflect unstable or noisy behavior, not true self-correction. But using uncertainty to decide when to ask the model to try again can genuinely help.

Why does this matter?

This has practical and safety implications for building reliable AI:

- Don’t assume that a model’s mid‑answer “Aha!” language means it has discovered a better reasoning path. Most of the time, it hasn’t.

- Intrinsic self-correction (the model fixing itself without help) appears weak here. Instead, external scaffolds—like prompts that ask for reconsideration at the right time—work better.

- Uncertainty can be useful as a “gate.” If the model seems unsure, asking it to reflect or retry is more likely to pay off.

- For trustworthy reasoning systems, methods like process supervision (rewarding correct intermediate steps) and uncertainty-aware prompting may be more reliable than hoping for spontaneous insight.

- From a safety standpoint, clearer, externally guided reasoning and uncertainty checks can make AI behavior more predictable and easier to monitor.

In short: AI “Aha!” moments are mostly an illusion in these settings, but smart prompting—especially when the model seems unsure—can turn shaky reasoning into better answers.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased to be actionable for follow-up research:

- Shift detection validity and scope

- Reliance on an LLM-as-judge (GPT-4o) and lexical/structural cues to label “reasoning shifts” may miss silent internal strategy changes or misclassify superficial hesitations; systematic human validation was only reported for MATH, not for crosswords or Rush Hour, and cross-judge robustness (e.g., Claude, Gemini) was not assessed.

- The rubric does not ground “qualitatively different strategies” in task-specific, verifiable operations (e.g., algebraic transformation types, crossword device switches, search policy shifts); build task-native parsers and state analyzers to validate actual strategy changes.

- No mechanistic analysis connects detected shifts to internal state changes (e.g., probing, causal tracing, logit lens, layer-wise surprisal spikes); measure whether hidden-state reorganizations occur absent textual cues.

- Power, thresholds, and statistical design

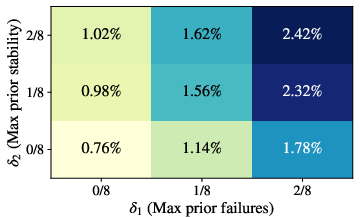

- “Aha!” definition estimates conditional correctness from only G=8 samples per problem–checkpoint–temperature, limiting power to detect small but meaningful improvements; quantify sensitivity and increase sample sizes or aggregate across checkpoints with hierarchical models.

- Threshold choices for prior failure/stability (δ1, δ2) and gain (δ3) are explored coarsely; perform principled sensitivity analyses (e.g., continuous ROC-style curves, FDR control) and report stability under alternative priors and Bayesian estimators.

- Observational regressions establish associations, not causality; design interventions that exogenously induce or suppress mid-trace pivots (without changing difficulty) to identify causal effects.

- Generalization across models and training regimens

- Study is dominated by small/mid-size open models (Qwen2.5 1.5B/7B, Llama 8B) with short GRPO runs (≤1k steps); test larger models, longer RL schedules, and diverse objectives (RLHF, DPO, process supervision, verifier-trained self-correction).

- Compare against base/SFT-only checkpoints and different reference policies to isolate whether GRPO specifically increases unstable inference or merely reveals it.

- Frontier closed models are only briefly checked for shift prevalence; extend to systematic multi-model comparisons under matched prompts/decoding and report per-model uncertainty calibration.

- Task and data coverage

- Only English and three domains are studied; add code generation/debugging, theorem proving, symbolic integration, program synthesis with unit tests, multi-modal reasoning (vision/text), interactive planning, and adversarial “insight” puzzles designed to require representational change.

- Rush Hour accuracy is near-zero, limiting conclusions about positive shifts; either scale model competence (curriculum, tool-augmented search) or use tasks with mid-range difficulty to observe helpful pivots.

- Synthetic crossword set and Rush Hour boards may not reflect real-world distributions; validate on naturalistic corpora and annotate ground-truth “device/strategy” labels to enable precise shift auditing.

- Prompting and decoding confounds

- Results may depend on the specific > /<answer> templates and “reconsideration” scaffolds; run ablations over prompt styles, reflection affordances, and stop criteria to test inducement of shifts vs genuine self-correction. > - Only nucleus sampling (p=0.95) and four temperatures are used; evaluate top-k, beam search, constrained decoding, and diverse sampling seeds to separate temperature-induced entropy from structural exploration. > - Analyze whether shift incidence and effect depend on trace length, position/timing of the pivot, and number of pivots per trace (early vs late, single vs repeated). > > - Uncertainty estimation and gating > - Average sequence entropy is a crude uncertainty proxy; compare against calibrated predictors (temperature scaling, Dirichlet/energy scores), self-consistency variance, ensembles, Monte Carlo dropout, and token-level change-point detectors for surprisal spikes. > - The top-20% entropy gate is ad hoc; tune thresholds per domain/model and test adaptive gates (e.g., quantile schedules, cost-aware policies) and local (segment-level) uncertainty triggers. > - Distinguish epistemic vs aleatoric uncertainty and assess whether different uncertainty types predict when reconsideration helps. > > - Extrinsic “reconsideration” intervention > - Lack of a critical control: compare Pass-2 with the cue vs Pass-2 without the cue (same decoding) to isolate cue-specific gains from simple second-sample improvements; also compare against self-consistency and majority-of-N baselines at equal token budgets. > - Quantify token, latency, and cost trade-offs for Pass-2 and entropy-gated interventions; report accuracy-per-token and cost-normalized gains. > - Characterize failure modes: when does the cue backfire (right→wrong), and can we train refusal or abstention policies under high entropy to avoid degradation? > > - Causal mechanisms and training dynamics > - The claim that shifts are “symptoms of unstable inference” is not mechanistically explained; analyze gradient dynamics, KL penalties, and reward shaping to see whether training explicitly rewards hedging language or exploratory rewrites. > - Examine how process supervision or verifier rewards change shift frequency/quality; do models learn to pivot toward verifiable checkpoints (e.g., plug-in check, unit tests)? > - Track whether beneficial pivots appear at specific training phases or curriculum stages (e.g., after exposure to certain feedback patterns), with denser checkpointing and intermediate reward logs. > > - Evaluation rigor and reliability > - Human–LLM agreement was reported for MATH only; replicate reliability studies for all domains, include cross-annotator agreement and adjudication protocols, and release gold-labeled subsets for benchmarking shift detectors. > - Control for multiple comparisons across many regressions and temperatures; report adjusted CIs and pre-register primary analyses. > - Report robustness to problem selection and difficulty calibration (e.g., stratify by verified hardness, near-miss answers) to avoid Simpson’s paradox from aggregating over heterogeneous items. > > - Definitions and measurement of “insight” > - The “Aha!” definition is tied to checkpoint-level aggregate improvements, not per-trace causal benefit; explore per-trace counterfactuals (e.g., same prefix with/without pivot) via controlled resampling or constrained decoding. > - Develop operational, task-grounded measures of representational change (e.g., algebraic form equivalence, crossword device switch, plan-structure edit distance) rather than linguistic self-reflection markers. > - Investigate whether some pivots are small but cumulatively useful (micro-corrections) versus rare “large” restructurings, and whether the former are undercounted by the current detector. > > - Safety and deployment implications > - Evaluate whether entropy-gated reconsideration increases hallucination length or introduces new errors in high-stakes settings; add abstention/verification layers and study human-in-the-loop oversight. > - Assess distribution shifts: do conclusions hold under domain transfer, noisy inputs, or adversarial prompts designed to elicit spurious “Aha” cues? > > These gaps outline concrete avenues to strengthen causal claims, broaden generalization, improve measurement fidelity, and translate uncertainty-aware interventions into cost-effective, reliable deployments.

Glossary

- Advantage (policy gradient): The advantage function measures how much better an action is than a baseline under a policy, used to weight updates in policy-gradient methods. Example: "group-normalized advantages"

- “Aha!” moment: A sudden mid-reasoning shift that purportedly leads to a correct solution, analogous to human insight. Example: "Do reasoning models have ``Aha!'' moments?"

- Average Marginal Effect (AME): In logistic regression, the average change in predicted probability associated with a one-unit change in a predictor. Example: "We report average marginal effects (AME)"

- Binomial (logit) GLM: A generalized linear model for binary outcomes using the logit link (logistic regression). Example: "Binomial(logit) GLM"

- Bootstrap confidence intervals: Nonparametric intervals built by resampling the data to quantify estimator uncertainty. Example: "validate robustness using bootstrap confidence intervals"

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): A prompting technique that elicits step-by-step intermediate reasoning from LLMs. Example: "Chain-of-Thought"

- Checkpoint: A saved snapshot of model parameters at a given training step used for evaluation or resuming training. Example: "hundreds of training checkpoints"

- Cluster-robust standard errors (SEs): Standard errors adjusted for within-cluster dependence, yielding valid inference under clustering. Example: "cluster--robust SEs"

- Cryptic Xwords: A class of crossword clues requiring deciphering hidden wordplay mechanisms (e.g., anagram, charade). Example: "Cryptic Xwords clues"

- Decoding temperature: A sampling parameter controlling randomness in generation; higher temperatures yield more diverse outputs. Example: "multiple decoding temperatures"

- Emergent capabilities: Apparent abrupt acquisition of new abilities in large models as scale or training changes. Example: "Emergent Capabilities."

- Entropy-gated intervention: A procedure that triggers model reconsideration only when measured uncertainty (entropy) is high. Example: "We develop an entropy-gated intervention"

- Expected correctness: The probability that a model’s sampled reasoning trace yields a correct answer. Example: "denote expected correctness."

- Fixed effects: Categorical controls (e.g., per-problem) in regression that absorb unobserved heterogeneity. Example: "problem fixed effects"

- Gestalt perspectives: Psychological theories emphasizing holistic restructuring in problem solving (insight). Example: "Gestalt perspectives on problem-solving"

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): An RL fine-tuning algorithm that compares groups of completions, extending PPO with group-normalized advantages and KL regularization. Example: "Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)"

- KL regularization: A penalty using Kullback–Leibler divergence to keep the learned policy close to a reference policy. Example: "KL regularization"

- Kappa (κ): An inter-rater agreement statistic correcting for chance agreement. Example: "\kappa!\approx!0.726"

- Least-to-Most prompting: A prompting method that decomposes a task into ordered subproblems from simpler to more complex. Example: "Least-to-Most prompting"

- LLM-as-judge: Using a LLM to evaluate outputs (e.g., label shifts or correctness) according to a rubric. Example: "LLM-as-judge"

- Logistic regression: A statistical model for binary outcomes modeling log-odds as a linear function of predictors. Example: "logistic regression"

- MATH-500: A benchmark subset for mathematical problem solving used to evaluate reasoning models. Example: "MATH-500"

- Normalized exact match: An evaluation metric comparing normalized predicted and gold answers for exact equality. Example: "normalized exact match"

- Odds ratio (OR): A multiplicative effect on odds; OR>1 increases odds, OR<1 decreases odds. Example: "OR"

- Policy (in RL): A distribution over actions given the current state/history that defines the model’s behavior. Example: "the model defines a policy "

- Process supervision: Training that rewards intermediate reasoning steps rather than only final outcomes. Example: "process supervision—rewarding intermediate reasoning steps"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A policy-gradient RL algorithm that constrains updates to stay close to the old policy. Example: "PPO"

- RASM: A metric intended to identify linguistic or uncertainty-based signatures of genuine insight. Example: "RASM"

- Reference policy: A fixed baseline policy used to regularize the learned policy (e.g., via KL). Example: "a frozen reference policy"

- Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF): Fine-tuning with human preference data via a reward model to guide policy learning. Example: "RLHF"

- Representational Change Theory: A theory of insight where restructuring the problem representation enables solution. Example: "representational change theory"

- RHour (Rush Hour) puzzles: Sliding-block puzzles requiring planning sequences of legal moves to free a target piece. Example: "RHour"

- Self-consistency: A decoding strategy sampling multiple reasoning paths and selecting the most consistent final answer. Example: "self-consistency"

- Shannon entropy: A measure of uncertainty of a probability distribution over next tokens. Example: "Shannon entropy "

- Split–merge aggregation: An evaluation technique that mitigates bias by aggregating over randomized splits and merges of judged outputs. Example: "split--merge aggregation"

- Top-p sampling: Nucleus sampling that draws from the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds p. Example: "top-"

- Trajectory (in RL): A sequence of actions (tokens) sampled from a policy during generation. Example: "A reasoning trace is a trajectory "

- Token-level uncertainty: Uncertainty measured at each decoding step via the next-token distribution. Example: "token-level uncertainty"

- Verifier model: An external model or tool used to check or validate the correctness of intermediate steps or outputs. Example: "verifier models"

- Zero-shot cue: A minimal instruction that elicits reasoning without task-specific examples. Example: "the zero-shot cue ``Letâs think step by step''"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a concise set of deployable applications that leverage the paper’s findings, with sector links, concrete product/workflow ideas, and key feasibility notes.

- Software, education, finance, healthcare: Entropy-gated second-pass prompting to boost accuracy

- Application: Automatically trigger a reconsideration prompt on items where the model’s sequence entropy is high to improve correctness on reasoning tasks (e.g., math, analytics, coding).

- Tools/products/workflows: Middleware or SDK that reads next-token log-probs to compute entropy, then appends a standardized “reconsideration” cue and re-queries the model; configurable thresholds and audit logs.

- Evidence: +8.41pp accuracy on MATH-500 when the reconsideration cue is applied.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to token-level probabilities/logprobs; ability to perform two-pass inference; domain-specific threshold calibration; added latency and cost.

- Customer support, legal/compliance, healthcare triage: Uncertainty-aware escalation or abstention

- Application: Gate higher-risk outputs with human review or abstain when entropy is high; trigger second-pass reflection before delivery.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Unsure” flags in chat/product UIs; route to human-in-the-loop queues; policy engines that enforce review for high-entropy items.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable uncertainty measurement; clear escalation policies; end-user consent to two-pass workflows.

- MLOps and model evaluation: Shift-aware training monitors and dashboards

- Application: Instrument RL/SFT runs to collect traces and monitor shift prevalence, temperature effects, and entropy distributions; avoid misinterpreting “Aha” illusions as progress.

- Tools/products/workflows: Training telemetry collectors; dashboards showing shift rate vs. accuracy; alerts when shift-induced accuracy drops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Storage of mid-trace logs; reproducible checkpoints; evaluator bias controls.

- Model safety and alignment: Replace presumed intrinsic self-correction with explicit verification

- Application: Stop treating mid-trace “Aha!” cues as reliable self-correction; instead, use verifiers, tool calls, and process supervision.

- Tools/products/workflows: Integrated verifier models for math/code; tool-use policies (calculators, theorem provers); process-supervision reward schemas.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tool integrations; process-level reward data; domain-specific verifier coverage.

- Prompting and inference policy: Temperature calibration by task

- Application: Tune temperature per domain (lower T for math-like tasks where shifts are harmful; careful experimentation for puzzles where benefits can appear at low T).

- Tools/products/workflows: Inference policy profiles by task (e.g., “Math-safe”: T≤0.3, reflection gating on entropy); A/B testing harnesses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust task routing; clear metrics and guardrails; avoid overfitting to cue words.

- Software engineering: IDE assistants that trigger tests/tools under uncertainty

- Application: When entropy is high, automatically run unit tests, static analysis, or formal checks; offer a “Re-evaluate” button.

- Tools/products/workflows: IDE plugins integrating entropy estimates, test runners, and second-pass prompts; commit gates for high-entropy diffs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Integration with CI tools; developer acceptance; log-prob access.

- Education and tutoring: Controlled “re-think” prompts for student-facing LLMs

- Application: Tutors trigger a second-pass explanation when the model is uncertain; avoid relying on spontaneous mid-trace shifts (which are rare/harmful).

- Tools/products/workflows: Classroom apps with entropy gating and paired explanations; analytics to track learning gains.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable entropy measures; alignment with curriculum; careful UX to avoid confusion.

- Analytics and BI: Risk-aware reporting modes

- Application: Tag high-entropy insights for validation; auto-run second-pass or alternative methods before surfacing decisions to stakeholders.

- Tools/products/workflows: BI pipelines that record entropy, run reconsideration, and mark validated outputs; review queues for compliance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational appetite for delayed responses; secure handling of intermediate traces.

- Benchmarking: Adopt the paper’s multi-domain suite and LLM-as-judge protocols

- Application: Use math, crosswords, and spatial puzzles to probe shift prevalence and effectiveness across temperatures and checkpoints.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open datasets and code; rubric-prompted LLM-as-judge with split–merge aggregation; bootstrap CIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Judge robustness; domain representativeness; compute for longitudinal evaluation.

- Policy and procurement: Minimum requirements for uncertainty-aware deployments

- Application: Require uncertainty gating and external verification for LLM systems in regulated settings; prohibit claims of “intrinsic self-correction” without evidence.

- Tools/products/workflows: Policy templates specifying uncertainty thresholds, human review criteria, and verification tooling; audit trails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sector-specific regulation; auditor access to logs/entropy; standards for acceptable uncertainty calibration.

Long-Term Applications

Below are applications that require further research, scaling, or ecosystem development to become feasible.

- Model architecture and training: Toward genuine intrinsic self-correction

- Application: Design methods where mid-trace shifts reliably improve accuracy (e.g., uncertainty-aware process supervision, calibrated exploration).

- Tools/products/workflows: New RLHF/GRPO variants that reward beneficial pivots; training datasets with labeled strategy changes; calibrated uncertainty training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Better uncertainty calibration; scalable annotation of shifts; evaluation standards for “insight.”

- Standardized uncertainty APIs and model telemetry

- Application: Providers expose stable token-level logprobs/entropy, per-segment uncertainty (think/answer), and trace hooks for production.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cross-vendor entropy APIs; observability stacks for LLM reasoning; privacy-preserving trace logging.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Provider cooperation; privacy and IP constraints; performance overhead management.

- Autonomous agents and planning (robotics, logistics, energy)

- Application: Entropy-gated plan revision—agents detect high-uncertainty steps and trigger systemic re-planning or tool-assisted checks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Planning stacks with uncertainty monitors; hybrid model–symbolic planners; certification of revision policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Well-calibrated uncertainty in embodied settings; safe fallback mechanisms; real-time constraints.

- Regulated domains (healthcare, finance, law): Auditable shift and uncertainty governance

- Application: Mandate uncertainty-aware re-evaluation and verifier use for decisions; collect trace evidence for compliance audits.

- Tools/products/workflows: Governance platforms that log entropy, second-pass outcomes, and verifier results; explainability reports.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory frameworks acknowledging uncertainty gating; data retention policies; clinical/financial validation.

- Education platforms: Adaptive curricula driven by model uncertainty

- Application: Adjust pedagogy dynamically—present alternative explanations, scaffold steps, or escalate to human tutors when uncertainty spikes.

- Tools/products/workflows: Learning management systems integrating entropy signals; personalization engines; outcome tracking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable per-learner calibration; fairness considerations; longitudinal studies of learning impact.

- Software verification: Formal methods triggered by uncertainty thresholds

- Application: When code-generation entropy crosses a threshold, invoke formal verification, symbolic execution, or fuzzing before accepting changes.

- Tools/products/workflows: Automated gates in CI/CD; policy-driven verification orchestration; risk-based code review flows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Toolchain maturity; computational cost; developer adoption.

- Improved evaluators and “insight” metrics

- Application: Develop judge models and metrics that distinguish superficial hesitation cues from genuine strategy restructuring with low false positives.

- Tools/products/workflows: New rubrics (beyond lexical cues), multimodal uncertainty signatures, calibrated evaluators with human-grounded benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality labels; cross-domain generalization; agreement with expert judgments.

- Consumer productivity apps: Trust-aware assistant behaviors

- Application: Personal assistants that surface “I’m uncertain—re-checking” states; auto-run alternative solution paths for math/logic tasks.

- Tools/products/workflows: UX patterns for uncertainty disclosure; optional second-pass toggles; user education on model limits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear communication standards; avoidance of over-reliance; privacy-safe telemetry.

- Enterprise MLOps: Insight-stability audits at scale

- Application: Periodic audits of reasoning stability across checkpoints/temperatures; continuous monitoring to catch drift toward harmful shifts.

- Tools/products/workflows: Audit pipelines, drift alerts, and remediation playbooks; enterprise dashboards (e.g., “Insight Manager”).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to production traces; storage/compute budgets; role-based access controls.

- Standards and certification: Uncertainty-aware performance claims

- Application: Industry standards that require demonstrating uncertainty gating and external verification for any claims of “self-correcting” reasoning.

- Tools/products/workflows: Certification programs; shared testbeds; reporting templates emphasizing conditional accuracy (with/without shifts).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; independent testing bodies; clear pass/fail criteria.

Notes across all applications:

- The paper shows spontaneous mid-trace shifts are rare and typically harmful; rely on extrinsic mechanisms (verifiers, tools, second-pass prompts) rather than presumed intrinsic “Aha!” behavior.

- Benefits are domain- and temperature-dependent; calibrate thresholds and inference policies by task.

- Entropy/logprob access is a central dependency; where unavailable, approximate uncertainty via surrogate signals (e.g., variance across self-consistency samples), with appropriate caveats.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.