Diffusion Language Models are Provably Optimal Parallel Samplers (2512.25014v1)

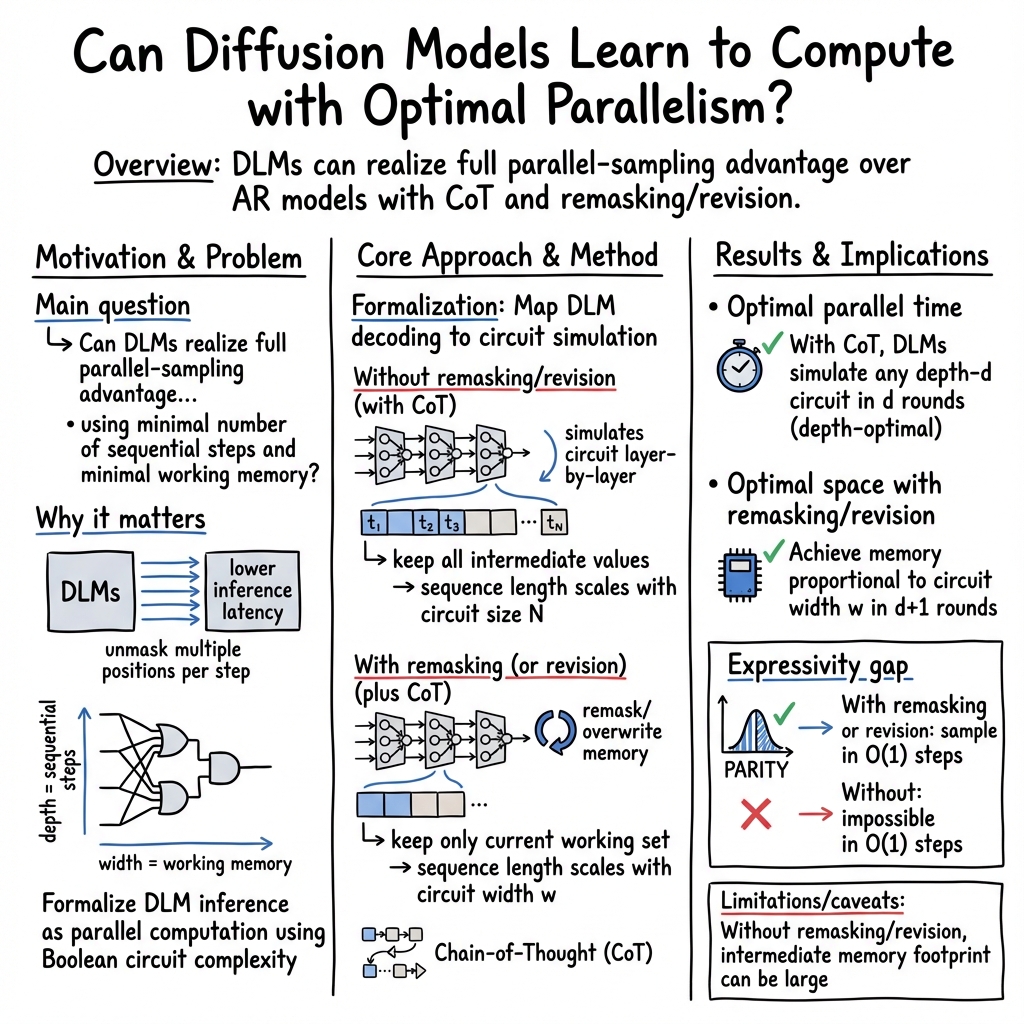

Abstract: Diffusion LLMs (DLMs) have emerged as a promising alternative to autoregressive models for faster inference via parallel token generation. We provide a rigorous foundation for this advantage by formalizing a model of parallel sampling and showing that DLMs augmented with polynomial-length chain-of-thought (CoT) can simulate any parallel sampling algorithm using an optimal number of sequential steps. Consequently, whenever a target distribution can be generated using a small number of sequential steps, a DLM can be used to generate the distribution using the same number of optimal sequential steps. However, without the ability to modify previously revealed tokens, DLMs with CoT can still incur large intermediate footprints. We prove that enabling remasking (converting unmasked tokens to masks) or revision (converting unmasked tokens to other unmasked tokens) together with CoT further allows DLMs to simulate any parallel sampling algorithm with optimal space complexity. We further justify the advantage of revision by establishing a strict expressivity gap: DLMs with revision or remasking are strictly more expressive than those without. Our results not only provide a theoretical justification for the promise of DLMs as the most efficient parallel sampler, but also advocate for enabling revision in DLMs.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper studies a new kind of text-generating AI called a diffusion LLM (DLM). Unlike traditional models that write one word at a time, DLMs can fill in many blanks at once. The authors ask: Can DLMs really generate text faster and more efficiently than traditional models? They build a mathematical framework to compare different ways of sampling (picking words) and prove that DLMs can be the best possible “parallel samplers” in terms of the number of steps and memory they use—especially if they are allowed to revise or re-mask tokens during generation.

Key Questions

The paper explores three main questions, stated in simple terms:

- If a target output (like a sentence or a distribution of sentences) can be produced in a small number of logical steps, can a DLM also produce it using the same number of steps?

- How much “scratch space” (extra tokens or memory) does a DLM need while it is generating the text?

- Do features like remasking (temporarily hiding a token again) and revision (changing a token to a different token) actually make DLMs more powerful at generating certain kinds of outputs?

How They Studied It

To make the comparison precise, the authors use a clean, simple model from computer science called a “Boolean circuit.” Think of it like this:

- Imagine a team doing a multi-step task (like assembling a gadget).

- The “depth” of the circuit is the number of steps in the assembly line (how many rounds you must do one after another).

- The “width” of the circuit is how many workers/tools you need doing things at the same time (how much space or memory the process needs at once).

Using this idea, the authors:

- Model a DLM as a process that fills in masked (blank) tokens over several rounds. Many positions can be filled in at once, so each round is parallel.

- Allow “chain-of-thought” (CoT), which is like giving the model scratch paper: it can write intermediate hints and working steps before writing the final answer.

- Study “remasking” (you can re-hide tokens and try again) and “revision” (you can change a token directly). These are like erasing and correcting parts of your draft.

With these tools, they prove how many rounds (time) and how much length (space) a DLM needs to produce any target output distribution.

Main Findings

1) DLMs with CoT can match the minimum number of sequential steps

- If some target output can be produced by a parallel procedure that takes d steps, then a DLM with chain-of-thought can generate it in exactly d rounds.

- This is “optimal”: you can’t do better than d rounds because the logic itself needs d steps.

- In contrast, traditional autoregressive (AR) models (which write one token at a time) need a number of steps that grows with the total size of the computation, not just its depth. In simple terms, AR models often need many more steps.

Why this matters: It gives a strong theoretical reason to believe DLMs can finish generation in fewer rounds than AR models when the task is naturally parallel.

2) Without editing, DLMs may use lots of intermediate space

- Even though DLMs can finish in few rounds, they may need to keep a lot of intermediate tokens around as scratch space during generation.

- This can make the sequences temporarily long or “heavy,” even if the final output is short.

3) With remasking or revision, DLMs achieve optimal space as well

- If you let the DLM re-mask tokens or revise them, it can erase or overwrite scratch work.

- The authors prove that with remasking or revision (plus chain-of-thought), a DLM can match the best-possible space (memory) as well as the best-possible number of steps.

- In simple terms: editing lets the model clean up its workspace as it goes, so it doesn’t have to carry around unnecessary parts.

4) DLMs with remasking or revision are strictly more expressive

- “Expressive” means able to generate more kinds of distributions within a fixed number of steps.

- The authors use a concrete example: sampling strings with even parity (an even number of 1s). They show:

- A DLM with remasking or revision can sample these strings in a constant number of steps.

- A DLM without remasking or revision cannot do this in a constant number of steps (even if its internal logic is strong within a standard class called AC0). This is a formal separation.

- This proves that allowing revision/remasking truly adds power, not just convenience.

5) Practical note on runtime vs rounds

- Even if DLMs use fewer rounds, each round may compute over many positions at once, which can require more raw computation per round than AR models (which compute one token at a time).

- If your hardware can handle lots of parallel work, DLMs can be faster in wall-clock time. If not, the speed advantage may be reduced or lost.

- So, theoretical “fewer rounds” is great, but actual speed depends on your hardware and implementation.

Implications and Impact

- DLMs are, in theory, the most efficient way to sample complex distributions in parallel: they can match the best number of steps and, with editing features, the best memory footprint.

- This gives a strong reason to invest in DLMs for faster inference (especially when your hardware supports large parallel workloads).

- It also strongly encourages adding “revision” (and/or “remasking”) to DLMs. These features don’t just polish results—they fundamentally make the model more capable in limited time.

- For builders of LLMs, this suggests:

- Design DLMs that can change or re-mask tokens during decoding.

- Use chain-of-thought as structured scratch space.

- Choose decoding orders and policies that exploit parallelism.

- Overall, the paper provides a solid theoretical backbone for why DLMs could be the future of fast, efficient text generation—given the right model features and hardware support.

Quick glossary of key terms

- Diffusion LLM (DLM): A model that starts with many masked tokens and uncovers them over several rounds, filling in many positions in parallel.

- Autoregressive (AR) model: A model that generates text one token at a time in sequence.

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): Letting the model write intermediate steps or reasoning before the final answer.

- Remasking: Hiding a previously revealed token again to resample it.

- Revision: Directly changing a revealed token to a different token.

- Circuit depth: Number of sequential steps needed. Think “how many rounds does the assembly line need?”

- Circuit width: How many things happen at the same time. Think “how many workers/tools do we need in a round?”

- Parity: Whether the number of 1s in a string is even or odd (even parity means an even number of 1s).

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased to guide actionable follow-up research.

- Practical realizability of the circuit abstractions

- How to train real DLMs (e.g., Transformers) to implement the specific constant-depth (or O(log d)) predictor and mask/remask policies required by the constructions.

- Impact of finite-precision computation, soft attention, and non-idealities on the assumed AC0/NC0 behavior and independence across positions.

- Chain-of-thought (CoT) requirements and learnability

- Methods for automatically discovering/learning the required CoT to simulate target circuits; data and optimization regimes needed to induce such scratchpads.

- Performance and robustness when CoT length is constrained (e.g., bounded by latency/compute) rather than polynomial or tied to circuit size N.

- Empirical validation that DLMs actually exploit CoT to realize the predicted parallel step reductions.

- Time vs wall-clock latency and compute

- Quantitative analysis of actual wall-clock speedups given hardware constraints (limited parallelism, memory bandwidth) and DLM per-step FLOP overheads.

- Scheduling strategies to minimize per-step compute (e.g., sparse attention, partial updates) while preserving the theoretical step count advantages.

- Space footprint without remasking/revision

- Formal lower bounds on the minimal sequence length L required to simulate a depth-d, size-N circuit without remasking/revision (beyond the constructive L = N upper bound).

- Whether there exist alternative scheduling/compaction schemes (without remasking/revision) that reduce L below N.

- Tightness and constants in space–time optimality with remasking/revision

- Whether the L = 2w + 2⌈log(d+1)⌉ (remasking) and L = w + ⌈log(d+1)⌉ (revision) bounds are tight; opportunities to reduce constants or eliminate the “+1” step.

- Cases where revision could reduce the number of steps versus remasking beyond the presented constructions.

- Scope of the expressivity separation

- How the parity-based separation extends to richer complexity classes (e.g., TC0 or beyond) and to more general distributions than parity-constrained uniform strings.

- Whether the separation persists if per-step circuits are stronger than AC0 (e.g., allowing counting/majority within a step).

- Lower bounds for approximate sampling (e.g., in total variation distance): how close can a DLM without remasking/revision get to the target distribution in O(1) steps?

- Assumptions on per-step circuit depth

- Consistency of assuming constant-depth per-step circuits “throughout” while allowing O(log d) depth in key constructions; implications when d scales with input length n.

- Resource accounting when both d and n grow: how to compare parallel step complexity with per-step circuit depth realistically.

- Remasking and revision mechanisms

- Concrete training procedures and forward processes that implement revision reliably; guarantees on stability and convergence when tokens are revised.

- Design and analysis of adaptive remasking policies (beyond the existence proofs): when to remask, how much to remask, and how to learn these policies end-to-end.

- Effects of remasking/revision on semantic coherence, constraint satisfaction, and alignment (e.g., avoiding destructive edits).

- Independence and randomness assumptions

- Impact of the assumption that p(x|x_t) factorizes across positions given x_t; potential benefits and risks of introducing controlled cross-position coupling in sampling.

- Requirements on randomness (per-position independent random bits) versus practical sampling (e.g., Gumbel noise, correlated RNG) and the effect on guarantees.

- Unmasking/remasking policy capabilities

- Power and limitations when the unmasking policy f is deterministic versus randomized or step-dependent; matching lower bounds that allow step-dependent f in the “no-remask” case.

- Characterizations of optimal decoding orders/policies for classes of distributions; trade-offs between order, steps, and footprint.

- Generality beyond binary vocabularies

- Overheads and artifacts introduced by binary encodings of larger vocabularies (e.g., invalid codewords, longer L); extensions that operate natively over large vocabularies.

- Conditioning, variable length, and stopping

- Treatment of variable-length outputs and stopping criteria in the framework; how to represent and reason about generation that ends early or adaptively.

- Interaction between input length, CoT length, and output length under fixed L; methods to handle mismatches and padding efficiently.

- Approximation tolerance and robustness

- Sensitivity of the constructions to approximation error in predictors and policies; trade-offs between fewer steps and small deviations in the target distribution.

- Sample complexity (data requirements) to learn predictors that approximate the desired circuits with high fidelity.

- Comparisons to advanced AR and hybrid methods

- Formal comparisons to speculative decoding, draft-and-verify, and other AR parallelization strategies; conditions under which DLM advantages persist.

- Hybrid designs that combine AR and DLM decoding to balance compute and latency.

- Extension to other modalities and structures

- How the results translate to non-text modalities or structured outputs (graphs, trees, images) where parallel constraints differ from linear sequences.

- Hardware-aware theoretical models

- Theoretical frameworks that incorporate bounded parallelism, memory hierarchies, and interconnect limits to predict real speedups more accurately.

- Clarity and completeness of lower-bound arguments

- A fully explicit, end-to-end proof that DLMs without remasking/revision cannot sample the parity-constrained distribution in O(1) steps under AC0 assumptions, including treatment of step-dependent policies and approximate sampling variants.

- Practical design guidance

- Concrete recipes for building and training DLMs with revision/remasking that achieve the predicted space–time optimality on real tasks.

- Benchmarks and metrics that directly measure “parallel steps,” memory footprint, and distributional fidelity to validate the theory empirically.

Glossary

- AC0: A family of constant-depth, polynomial-size circuits with unbounded fan-in AND/OR gates. "It is well known that is not in "

- Absorbing masks: Special mask tokens that act as absorbing states in discrete diffusion forward processes. "formalized categorical forward kernels and popularized absorbing masks,"

- Addition modulo 2: Binary addition mod 2 (equivalent to XOR). "Let ⊕ be addition modulo 2."

- Autoregressive (AR) generation: Sequential text generation where tokens are produced one at a time based on prior context. "have recently emerged as a promising alternative to autoregressive (AR) generation"

- Boolean circuit: A layered network of logic gates modeling parallel computation. "A Boolean circuit is a model that characterises the complexity of carrying out certain parallel computations."

- Categorical forward kernels: Transition rules defining masking/noising in discrete diffusion over categorical variables. "formalized categorical forward kernels and popularized absorbing masks,"

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): Generating intermediate reasoning tokens before the final output to improve problem solving. "Chain of Thought (CoT) is the technique in LLMs that allows the output to a prompt to appear after generating some intermediate tokens."

- Circuit complexity: The study of computational resources (time/depth, space/width) required by circuits. "by formalizing them through the lens of circuit complexity"

- Circuit depth: The number of layers; the minimal sequential steps needed to compute. "Depth represents the minimum number of sequential steps to carry out the computation represented by "

- Circuit width: The maximum number of gates per layer; the minimal memory bits needed. "and width represents the minimum number of memory bits needed to carry out the computation."

- Constant-depth circuits: Circuits with a fixed number of layers independent of input size. "Throughout this paper, we assume that DLMs all consist of constant-depth circuits."

- D3PM: A discrete diffusion model framework for categorical data (Discrete Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models). "The seminal work of D3PM~\citep{austin2021structured} formalized categorical forward kernels and popularized absorbing masks,"

- DAG (Layered directed acyclic graph): A directed graph without cycles organized in layers, used to define circuits. "A circuit is defined as a layered directed acyclic graph (DAG)."

- Decoding order: The sequence/strategy for choosing which positions to unmask during inference. "it is observed that decoding order can greatly affect the performance of DLMs"

- Denoising: Removing noise (masks) to reconstruct clean tokens in diffusion decoding. "DLMs decode by iteratively denoising masked sequences,"

- Diffusion LLMs (DLMs): Discrete diffusion-based text generators enabling parallel token sampling. "Diffusion LLMs (DLMs) have emerged as a promising alternative to autoregressive models for faster inference via parallel token generation."

- Encoding (2-bit encoding): Mapping tokens and masks to fixed-length binary codes for circuit modeling. "we will use a fixed 2‑bit encoding"

- Expressivity gap: A formal difference in representational power between model variants. "a strict expressivity gap: DLMs with revision or remasking are strictly more expressive than those without."

- Forward process: The masking/noising procedure that independently masks tokens before denoising. "These constraints arise from the definition of the forward process, where tokens at different positions are independently masked to ."

- Hard attention mechanism: Attention that selects only the highest-scoring position. "Transformers with hard attention mechanism, where each attention block can only attend to the position with the largest score,"

- Inference-time scaling: Increasing computation or parallelism at inference to improve speed/quality. "a world increasingly attuned to the value of inference-time scaling"

- KV caching: Storing key/value tensors in Transformers to accelerate autoregressive decoding. "an autoregressive Transformer with KV caching"

- MAJORITY gate: A threshold gate that outputs 1 if more inputs are 1 than 0. "allow gates with unbounded in-degrees,"

- Mask token (M): A special token indicating a position is masked/noised. "We also consider a mask token ."

- Multiplexer: A circuit that selects among multiple inputs based on a control signal (e.g., layer index). "A useful construction of multiplexers."

- NCk: Problems solvable by poly-size circuits of depth O((log n)k) with bounded fan-in. "A problem is in where "

- Parity function (PARITY): The XOR of all bits of a string; 0 for even parity. "Boolean function is defined as follows."

- Parallel sampling: Generating multiple tokens concurrently rather than sequentially. "by formalizing a model of parallel sampling"

- Predictor (p(·|x_t)): The DLM component that outputs token distributions for masked positions. "Central to a diffusion LLM (DLM) is a predictor "

- Probabilistic AC0 circuits: AC0 circuits that use random bits in their computation. "this theorem can be directly extended to probabilistic circuits as follows."

- Remasking: Re-noising previously unmasked tokens to resample them during inference. "Remasking is an inference-time mechanism that allows already unmasked tokens to be re-masked (noised) and resampled (denoised)."

- Revision: Changing an already unmasked token to a different token during generation. "We refer to this as DLMs with revision."

- TCk: Threshold circuit class with unbounded fan-in MAJORITY gates. "the corresponding complexity class is called ."

- Transformer: An attention-based neural architecture widely used for language modeling. "most current DLM implementations are based on Transformers"

- Uniform distribution (Ur): The distribution where all r-bit strings are equally likely. "sampled from "

- Unbounded in-degrees: Gates allowed to have arbitrarily many inputs (fan-in). "If we allow to have unbounded in-degrees, the corresponding complexity class is called ."

- Unmasking policy: The rule/function that selects which masked positions to reveal each round. "we denote the set of positions to be unmasked by "

- Working memory footprint: The amount of intermediate state/tokens maintained during generation. "we also analyze the working memory footprint (\Cref{thm:cotr}) of DLMs"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a concise set of actionable use cases that can be deployed now, organized by sector, with indicative tools/workflows and feasibility notes.

- Revision-enabled DLM decoding engines (software, AI infrastructure)

- What: Enable token revision during inference to minimize intermediate memory footprint while keeping optimal step count.

- Tools/workflows: Inference SDKs with “revision” mode; tokenizer/predictor APIs that permit changing previously unmasked tokens; telemetry to track footprint.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model trained with a forward process that supports revision; independence of per-position sampling preserved; integration with existing Transformer-based DLMs.

- Remasking-based policy optimization (software, MLOps)

- What: Use dynamic remasking to resample low-confidence spans and free working memory in iterative denoising.

- Tools/workflows: Policy learners for selecting remask sets; step-dependent unmask/remask schedules; confidence thresholds from logits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model supports remasking at inference; API exposure for per-step policies; task distributions benefit from re-noising.

- Depth-aware generation schedulers (software, platform engineering)

- What: Select the number of DLM rounds by estimating a task’s “circuit depth,” switching from AR to DLM for low-depth tasks (e.g., entity extraction, template filling, form completion).

- Tools/workflows: “Depth estimator” heuristics; routing layer that chooses AR vs. DLM; A/B experiments on latency vs. quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rough mapping of task structure to low depth; stable DLM quality on parallel decoding; sufficient GPU parallelism.

- Parallel autocomplete and code infill (developer tools)

- What: Use DLMs for multi-token infill/edit operations where many positions can be denoised at once; apply revision for quick corrections.

- Tools/workflows: IDE plugins with parallel infill; mask-based edit buffers; two-step “draft + revise” routines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU/TPU kernels optimized for multi-position attention; predictable behavior under CoT; strong language modeling quality.

- Batch inference latency reduction (cloud inference, MLOps)

- What: Exploit parallel token decoding to reduce wall-clock latency for batch requests with small sequential depth.

- Tools/workflows: Kernel libraries tuned for masked decoding; scheduling to pack sequences; KV-cache strategies adapted to DLM.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware supports high degrees of parallelism; FLOP overhead acceptable relative to AR; careful memory management to avoid footprint spikes.

- Memory-footprint management for production SLAs (MLOps)

- What: Adopt revision/remasking to keep space complexity near-optimal, lowering peak VRAM/RAM per request to increase throughput.

- Tools/workflows: Footprint monitors; per-step memory budgets and remask triggers; autoscaling based on observed width-like needs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Revision/remasking modes enabled; accurate telemetry; step budgets enforceable.

- Benchmarking by parallel complexity (academia, evaluation)

- What: Create benchmarks that label tasks by estimated “depth” and “width,” comparing AR vs. DLM latency/quality under fixed round budgets.

- Tools/workflows: Datasets partitioned by structural complexity; metrics for sequential steps vs. memory footprint; parity-style stress tests for expressivity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Useful approximations of depth/width for language tasks; standard evaluation harnesses; reproducible DLM inference settings.

- Curriculum and teaching materials on parallel sampling (education)

- What: Integrate the paper’s circuit-complexity lens into courses on algorithms, ML systems, and computational complexity.

- Tools/workflows: Lecture modules; labs on DLM vs. AR decoding; assignments on depth/width tradeoffs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accessible DLM implementations and datasets; institutional adoption.

- Energy and cost guidance for inference-time scaling (policy, operations)

- What: Provide procurement and deployment guidance to choose DLMs for low-depth tasks, balancing FLOPs vs. parallel efficiency.

- Tools/workflows: Cost models for AR vs. DLM at various batch sizes; energy dashboards; SLAs aligned with round budgets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Transparent energy metering; task complexity tagging in pipelines; governance for model selection.

Long-Term Applications

The following use cases require further research, scaling, or engineering development before broad deployment.

- Algorithm-to-DLM compilers (software tooling)

- What: A DSL and compiler that translates problem specifications (or circuits/workflows) into optimal DLM decode plans (round schedules, remask/revise policies).

- Tools/products: “Depth-aware” compilers; static analyzers for CoT length; multiplexer-like control logic for step-dependent policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust mapping from task structure to circuit depth/width; stable APIs for step-conditional policies; verification harnesses.

- Hardware co-design for DLM parallelism (semiconductors, AI accelerators)

- What: New accelerators optimized for masked multi-position attention, fast remasking, and revision operations (including step-conditional compute).

- Tools/products: Custom kernels; memory hierarchies tuned for alternating blocks; schedulers minimizing synchronization overhead.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry adoption; compiler/runtime integration; sustained research on workloads and kernels.

- Training regimes for revision-aware predictors (ML research)

- What: Learn forward processes and training objectives that explicitly support token revision, preserving independence constraints while improving expressivity.

- Tools/products: Losses for revision reliability; synthetic tasks to learn step-dependent behavior; architectures with controllable per-position randomness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable training; datasets and evaluation for revision; safety and robustness under revision.

- Adaptive round control and CoT budgeting (product, research)

- What: Agents that adjust decode rounds per input in real time based on mask patterns, uncertainty, and depth heuristics to balance speed and quality.

- Tools/products: Controllers with feedback signals; QoS-aware round schedulers; policy learning for remask/revise triggers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable uncertainty estimates; online learning frameworks; guardrails to prevent collapse in hard cases.

- Expressivity-enhancing forward processes (ML theory, systems)

- What: Design new masking/revision processes that unlock richer distributions in constant steps (beyond parity-style separations), with provable properties.

- Tools/products: Theoretical analyses; canonical task suites; experimental forward-process libraries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Guarantees on independence and correctness; tractable training; alignment considerations.

- Standards for inference-time scaling and compute budgets (policy, governance)

- What: Develop regulatory and industry standards for round budgets, memory footprints, and energy accounting in large-scale LLM inference.

- Tools/products: Reporting templates; compliance checkers; recommended practices for choosing AR vs. DLM by task complexity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; measurable depth/width proxies; interoperability across vendors.

- Robotics and edge decision-making with DLMs (robotics, embedded AI)

- What: Apply DLMs to time-critical, low-depth planning or instruction generation where parallel sampling reduces latency on-device.

- Tools/products: Edge inference stacks with masked decoding; revision-enabled planners; safety monitors for step-bounded decisions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: On-device accelerators; strict latency/energy envelopes; robust behavior under partial parallelization.

- Clinical documentation and summarization (healthcare)

- What: Integrate DLMs for fast parallel summarization of structured EHR sections; apply revision to correct inconsistencies without full regeneration.

- Tools/products: Healthcare-specific DLMs; audit trails for revisions; privacy-preserving deployment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; bias and safety evaluations; data governance.

- Real-time financial text analysis and templating (finance)

- What: Use DLMs for parallel extraction/templating in filings and news streams where structure suggests low-depth decoding.

- Tools/products: Compliance-aware pipelines; revision-based corrections; latency-optimized inference services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model auditability; risk controls; domain adaptation.

Notes on cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies:

- The practical win relies on tasks that admit low parallel depth; when hardware parallelism is limited, wall-clock gains may be reduced despite optimal step counts.

- Revision and remasking must be supported by the model’s forward process and inference APIs; training procedures should be adapted accordingly.

- Independence of per-position randomness (a modeling assumption used in proofs) should be respected or carefully relaxed in implementations.

- Estimating “depth” and “width” for natural language tasks will require heuristics and empirical validation; mismatches can impact latency/quality trade-offs.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.