RoboMirror: Understand Before You Imitate for Video to Humanoid Locomotion

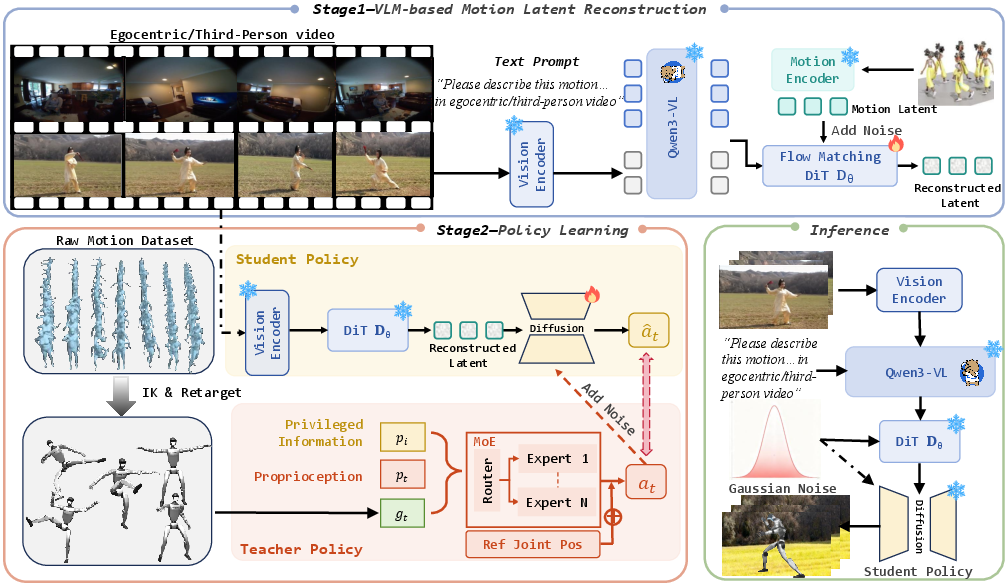

Abstract: Humans learn locomotion through visual observation, interpreting visual content first before imitating actions. However, state-of-the-art humanoid locomotion systems rely on either curated motion capture trajectories or sparse text commands, leaving a critical gap between visual understanding and control. Text-to-motion methods suffer from semantic sparsity and staged pipeline errors, while video-based approaches only perform mechanical pose mimicry without genuine visual understanding. We propose RoboMirror, the first retargeting-free video-to-locomotion framework embodying "understand before you imitate". Leveraging VLMs, it distills raw egocentric/third-person videos into visual motion intents, which directly condition a diffusion-based policy to generate physically plausible, semantically aligned locomotion without explicit pose reconstruction or retargeting. Extensive experiments validate the effectiveness of RoboMirror, it enables telepresence via egocentric videos, drastically reduces third-person control latency by 80%, and achieves a 3.7% higher task success rate than baselines. By reframing humanoid control around video understanding, we bridge the visual understanding and action gap.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Explaining “RoboMirror: Understand Before You Imitate for Video to Humanoid Locomotion”

1) What is this paper about?

This paper introduces RoboMirror, a new way to make humanoid robots move by watching videos. Instead of copying exact body poses from a person in the video, the robot first “understands” what kind of movement is happening (the intent), and then makes its own safe, realistic version of that movement. It works with both first-person videos (what someone sees through their own eyes) and third-person videos (watching someone else from the side), without needing to guess human joint positions frame by frame.

2) What questions are the researchers asking?

They focus on simple but important questions:

- Can a robot learn to move by truly understanding what it sees in a video, not just copying body angles?

- Can we avoid the slow and error-prone steps of pose estimation (guessing body joint positions) and retargeting (mapping a human body to a robot body)?

- Will this approach be faster, more reliable, and work in the real world?

3) How does RoboMirror work?

Think of the system as three parts that work like a “see → understand → act” pipeline:

- Understand the video: A Vision-LLM (VLM) looks at the video and turns it into a compact summary (a “latent”) that captures what’s going on, like “walking forward through a hallway” or “turning left around a table.” This works for both first-person and third-person videos.

- VLM = a smart model trained to understand pictures/videos and text together.

- Rebuild the motion idea: A diffusion model uses that summary to create a “motion intent” latent. You can think of diffusion like cleaning up a blurry photo in several steps until it’s clear. Here, it turns the high-level idea (“walk forward, avoid obstacles”) into a motion plan that makes physical sense.

- “Latent” = a compact code that represents important information.

- The key idea: instead of matching video features directly to robot actions, RoboMirror reconstructs a motion plan that already respects how bodies move.

- Generate robot actions: A control policy (the robot’s brain) uses the motion intent to produce smooth joint movements. The policy is trained in two stages:

- A “teacher” (an expert policy) is trained in simulation with extra information (like perfect physics details) to get very good at tracking motions.

- A “student” (a diffusion-based policy) learns from the teacher how to produce actions using only normal robot sensors plus the motion intent. This makes it ready for the real world.

In short: the video is turned into understandable “movement goals,” those goals are rebuilt into a physically meaningful plan, and then the robot turns that plan into safe, smooth motion—no pose estimation or retargeting needed at run time.

4) What did they find, and why does it matter?

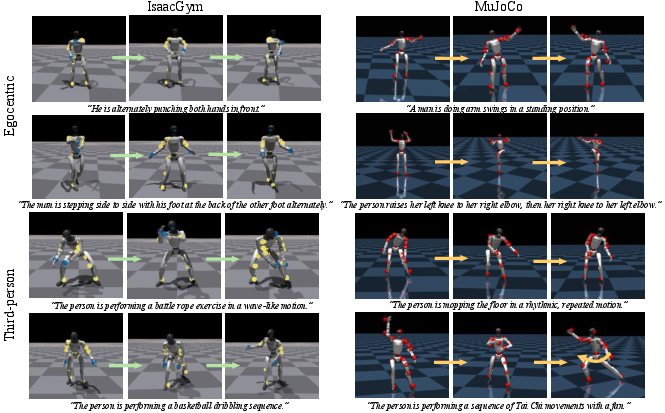

The researchers tested RoboMirror in simulation (IsaacGym and MuJoCo), on datasets with first-person and third-person videos (Nymeria, Motion-X), and on a real humanoid robot (Unitree G1). They compared it to pose-based methods.

Here are the highlights:

- Much faster: They cut control latency by about 80% (from about 9.22 seconds to about 1.84 seconds). This means the robot responds more quickly to video inputs.

- More reliable: RoboMirror achieved a higher task success rate (+3.7% compared to baselines). It also tracked movements with lower errors, especially avoiding the chain of mistakes that happen when you estimate human poses then retarget them to a robot.

- Works with first-person videos: It can generate reasonable walking and turning just from egocentric view (what the wearer sees), even though you can’t see the person’s body in that view. Traditional pose-estimation pipelines struggle here.

- Telepresence: The robot can “follow along” with what someone wearing a camera is doing, as if the robot were there too.

Why this matters: Robots that understand the scene and the goal (not just copy shapes) can be safer, more robust, and more adaptable in the real world.

5) What are the bigger impacts?

If robots can understand before they imitate, several good things follow:

- Easier control from everyday videos: You can guide a robot from common videos without special motion capture suits or complex pose-processing steps.

- Faster, more dependable operation: Less waiting and fewer failure points means better real-world performance.

- Telepresence and assistance: A person could wear a camera and have a robot mirror their intent at a distance—for example, guiding a robot through a building.

- A foundation for more complex skills: The same idea (understand → reconstruct intent → act) could be extended from walking to hands and manipulation, making general-purpose humanoids more practical.

In short, RoboMirror moves robots closer to how people learn: see, make sense of what’s happening, then act in a way that fits the situation.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future work could address:

- Real-world quantitative evaluation is missing: the paper claims direct deployment on the Unitree G1 but reports no on-robot metrics (success rate, falls, tracking error, energy consumption, latency, cycle time). Provide reproducible, task-defined, quantitative results for telepresence and third-person imitation on hardware.

- Streaming, closed-loop video control is not demonstrated: the system operates on pre-segmented 5-second clips. Evaluate continuous, real-time egocentric/third-person video ingestion with end-to-end latency, update rate, drift correction, and robustness to changing intent mid-trajectory.

- Lack of robot-centric environment perception during control: the student policy uses only proprioception (no vision/depth/LiDAR). Test locomotion in obstacle-rich or uneven environments and integrate exteroceptive sensing to ensure scene-aware, collision-free motion.

- Long-horizon behavior and transitions remain unexplored: assess performance on minutes-long sequences with multi-step goals (e.g., walking, turning, stopping, navigating to a location), including temporal consistency and recovery after disturbances.

- Robustness to egocentric video artifacts is not quantified: evaluate sensitivity to head-mounted camera motion (rapid yaw/pitch/roll), motion blur, low light, occlusions, FOV changes, and rolling shutter effects common in first-person videos.

- Generalization to unseen actions and OOD content is unclear: design splits and tests where actions, environments, and actors are genuinely novel, and quantify failure rates, graceful degradation, and fallback behaviors.

- “Retargeting-free” is only at inference; training still uses retargeted motion: investigate training without retargeted human-to-robot motion (e.g., robot-native motion corpora, self-supervised bootstrapping) and measure performance differences.

- Hardware generalization is untested: evaluate zero-shot or few-shot transfer to multiple humanoids with different kinematics/actuation (e.g., Apollo, Digit, NAO) and analyze how motion latent distribution shifts across embodiments.

- Safety and stability guarantees are not formalized: add constraints or monitors for contact forces, foot placement, center of mass margins, and fall avoidance; quantify safety incidents and introduce runtime safeguards.

- Compute and deployment constraints are unspecified: benchmark on-board vs off-board inference for Qwen3-VL and diffusion policy (FPS, memory, power), network reliability in telepresence, and the feasibility of running at typical control rates (100–500 Hz).

- Baseline coverage is limited: compare against strong, state-of-the-art pose-estimation pipelines (e.g., 3D pose with temporal smoothing, advanced retargeters), and modality-driven methods (LeVERB, RoboGhost, CLONE), with matched training data and evaluation protocols.

- Interpretability and controllability of motion latents are not addressed: develop tools to visualize, edit, and constrain latent intent (direction, speed, gait type), and quantify how prompt wording or latent manipulations affect generated motion.

- Temporal alignment and speed control are under-evaluated: test tasks requiring variable tempo (slow/fast walking, pauses), and measure how video timing maps to robot velocity and cadence; introduce metrics for tempo fidelity.

- Domain mismatch between video environment and robot environment is unstudied: when the demonstration video’s scene differs from the robot’s scene, quantify how intent transfers and add mechanisms (e.g., environment re-grounding, scene-level invariances).

- Failure-mode taxonomy and analysis are absent: document and categorize common failures (e.g., loss of balance in sharp turns, inaccurate foot placement, drifting heading), quantify their frequency, and propose targeted fixes.

- Whole-body coordination beyond locomotion is not validated: despite claims of extensibility, there is no quantitative evaluation of arm/hand involvement (e.g., carrying objects while walking). Test coordinated upper–lower-body tasks.

- Data efficiency and scaling laws are unknown: measure performance vs. dataset size (more/less Nymeria/Motion-X), clip length, and diversity; explore semi/self-supervised training from unlabeled videos to reduce reliance on paired video–motion data.

- VLM prompt sensitivity is not studied: evaluate robustness to different prompts, languages, and prompt-free settings; assess whether prompt engineering materially affects motion latent reconstruction and downstream control.

- Architectural choices for motion-latent reconstruction are narrow: compare the 16-layer MLP + AdaLN flow-matching approach to transformer-based sequence models, conditional priors, score-based diffusion, and recurrent architectures, especially for long temporal horizons.

- Student-policy learning stability and guarantees are not provided: formalize the DAgger-like training’s convergence and robustness without privileged information; quantify performance under significant dynamics randomization and actuator degradation.

- Synchronization and calibration between VLM latents and robot state are not discussed: define how to align video-derived intent with robot orientation, heading, and coordinate frames, especially for third-person videos with moving cameras.

- Multi-modal fusion is unexplored: investigate combining video with language, audio, or onboard vision to disambiguate intent and improve robustness; quantify gains from multi-view inputs (egocentric + third-person).

- Cross-simulator quantitative transfer is thin: beyond qualitative figures, provide standardized metrics and statistical significance for IsaacGym → MuJoCo transfer, including contact stability and trajectory fidelity.

- Ethical, privacy, and security considerations around egocentric telepresence are unaddressed: outline safeguards for sensitive visual content, misuse prevention (e.g., copying risky motions), and protocols for human-in-the-loop oversight.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper’s retargeting-free, video-to-locomotion pipeline (validated in IsaacGym/MuJoCo and on a Unitree G1 humanoid) enables the following practical uses that can be deployed now:

- Telepresence locomotion from egocentric videos for site inspection and patrol — Sectors: energy, manufacturing, logistics, security — Tools/Products: operator chest/helmet camera; Qwen3-VL-4B-Instruct; motion-latent reconstructor (DiT); diffusion-based student policy on humanoid (e.g., Unitree G1) — Workflow: operator streams first-person video → VLM extracts visual intent → DiT reconstructs motion latent → student policy generates robot actions without pose estimation — Assumptions/Dependencies: stable network streaming; moderate terrain difficulty; on-robot compute for real-time denoising (DDIM with few steps); basic safety layers (contact/obstacle checks); sufficient lighting and video quality

- Rapid third-person imitation for event coverage, retail demo replication, and interactive experiences — Sectors: entertainment, retail, experiential marketing — Tools/Products: “Video-to-Locomotion” player that loads third-person clips; onboard policy; lightweight deployment app — Workflow: curated video clips → VLM semantic latent → motion latent reconstruction → robot executes semantically aligned locomotion — Assumptions/Dependencies: well-framed third-person videos; limited need for upper-body manipulation; stage/venue safety constraints

- Low-latency teleoperation interface for humanoid locomotion — Sectors: robotics integrators, teleoperations platforms — Tools/Products: RoboMirror control module integrated into existing teleop stacks; SDK/API exposing a “video-conditioned action” endpoint — Workflow: video input stream → latent-driven policy → actions (1.84 s pipeline vs. 9.22 s pose-retarget pipelines) — Assumptions/Dependencies: reliable VLM inference latency; operator training and UI; fallback controls (e.g., stop/override)

- Video-driven skill harvesting to reduce motion dataset curation costs — Sectors: robotics, software tooling, simulation — Tools/Products: “Vid2Skill” batch processor to convert large video corpora into motion latents; training scripts for teacher MoE and student diffusion policy — Workflow: bulk ingestion of internet/enterprise video → VLM latents → motion latent reconstruction → policy training on motion-latent sequences — Assumptions/Dependencies: rights to use videos; domain randomization to improve transfer; bias/coverage analysis of source videos

- Simulation-to-real research pipeline for academic labs — Sectors: academia (robotics, CV, NLP) — Tools/Products: reproducible training stack (IsaacGym → MuJoCo → Unitree G1), evaluation metrics (Succ, E_MPJPE, E_MPKPE, R@3, FID) — Workflow: teacher MoE via PPO (privileged info) → student diffusion without privileged info → cross-engine tests → real-robot trials — Assumptions/Dependencies: access to simulation licenses and humanoid platforms; compute for VLM and diffusion training/inference

- Motion generation for animation/VR from videos (without manual MoCap) — Sectors: media, gaming, virtual production — Tools/Products: VAE decoder to convert reconstructed motion latents to SMPL-X sequences; asset export pipelines — Workflow: third-person or egocentric video → motion latent reconstruction → decode to motion for avatars — Assumptions/Dependencies: animation toolchain compatibility; quality checks for kinematic plausibility; IP/licensing for video sources

- Robotics education and prototyping — Sectors: education, makerspaces — Tools/Products: course modules demonstrating VLM-conditioned control, lab kits (simulation + a small humanoid), notebooks covering motion latent reconstruction — Workflow: students collect videos → build motion-latent datasets → train and deploy student policies to simulate and small-scale robots — Assumptions/Dependencies: simplified hardware; guardrails for safe locomotion; curated video tasks

- Policy sandboxing and safety testing for video-conditioned robotics — Sectors: public policy, standards bodies, enterprise compliance — Tools/Products: testbeds using RoboMirror to evaluate privacy risks (egocentric video), response latencies, failure modes — Workflow: run standardized scenarios (e.g., varying lighting, crowd density) → measure control quality and safety metrics → document best practices — Assumptions/Dependencies: access to facilities and instrumentation; clear data-handling protocols; collaboration with ethics/legal teams

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, safety certification, manipulation capability, or broader ecosystem support before routine deployment:

- General video-conditioned whole-body control including manipulation — Sectors: household robotics, industrial service robots, healthcare — Tools/Products: extended VLMs with fine-grained hand/object reasoning; contact-aware diffusion policies; multimodal sensing (vision + tactile) — Dependencies: robust hand perception and contact dynamics; safety-critical planning; real-time scene understanding and reactivity

- Personalized assistive care robots learning from caregiver/user videos — Sectors: healthcare, eldercare, rehabilitation — Tools/Products: “Care-By-Video” training suite; personalization layer using user-specific video demonstrations; compliance logging — Dependencies: medical device safety standards; reliable fall/obstacle avoidance; ethical data use (egocentric video privacy and consent)

- Disaster response and hazardous environment mirroring — Sectors: public safety, firefighting, mining — Tools/Products: ruggedized humanoids; telepresence workflows with egocentric feeds from responders; autonomy overlays for stability — Dependencies: operation in dust/smoke/low-light; wide domain randomization; robust comms; fail-safe behaviors under extreme dynamics

- Multi-robot video-conditioned telepresence at scale — Sectors: logistics, security, venue operations — Tools/Products: orchestration layer mapping video streams to multiple robots; coordination and scheduling — Dependencies: synchronization across fleets; bandwidth and compute scaling; standardized robot interfaces

- Standards and certification for video-conditioned control — Sectors: policy, standards, insurance — Tools/Products: benchmark suites (latency, success rate, failure recovery), conformance tests, privacy-by-design frameworks for egocentric video — Dependencies: consensus among regulators, insurers, and manufacturers; incident reporting and auditing mechanisms

- Marketplace and middleware for Video-to-Locomotion APIs — Sectors: robotics software, cloud services — Tools/Products: cross-device “RoboMirror API” offerings; SDKs for Qwen-family VLMs and motion diffusion; adapters for different humanoid kinematics — Dependencies: vendor cooperation; licensing for VLMs/datasets; device abstraction and safety policies

- Human–robot co-learning with wearables — Sectors: sports coaching, physical therapy, workplace training — Tools/Products: wearable egocentric capture + robot imitation; analytics on motion quality and adherence — Dependencies: robust generalization across users; strong privacy controls; interpretability and feedback for human coaches

- Ethical and legal governance frameworks for egocentric-video-driven robotics — Sectors: policy, enterprise compliance, privacy tech — Tools/Products: consent management, on-device anonymization, secure data pipelines — Dependencies: clear legal guidelines on video usage and retention; public trust and communication; technical safeguards against misuse (e.g., identity leakage)

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies that affect feasibility

- Hardware: capable humanoid platforms (e.g., Unitree G1) with reliable locomotion and safety supervisors; on-robot compute or edge offload for VLM/diffusion inference.

- Data and models: access to high-quality video inputs; robust VLMs (Qwen3-VL or successors) and motion-latent reconstructor; domain coverage beyond Nymeria and Motion-X.

- Safety: obstacle avoidance, contact and balance monitoring; emergency stop/override; compliance with venue and occupational safety rules.

- Performance: latency targets appropriate to application (1.84 s pipeline may need further reduction for tight real-time teleop); resilience to lighting, motion blur, and occlusions.

- Governance: video privacy, consent, IP/licensing for training and deployment; auditability and explainability of decisions under video-conditioned control.

Glossary

- Adaptive Layer Normalization (AdaLN): A conditioning normalization technique that modulates activations using learned affine parameters derived from a conditioning signal. "inject conditions via AdaLN~\citep{huang2017arbitrary}"

- Action generator: A module that outputs low-level control commands; here, produced via a diffusion process for robot actions. "a diffusion-based action generator"

- Center of Mass (CoM): The point representing the average position of mass in a body, used for assessing balance/stability. "center of mass"

- Center of Pressure (CoP): The point of application of the ground reaction force; used alongside CoM to assess stability. "center of pressure"

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism that conditions one sequence on another (e.g., motion on video latents). "with cross-attention blocks attending to the video latents"

- Cross-modal alignment: Aligning representations across different modalities (e.g., vision and motion) for coherent mapping. "robust cross-modal alignment without separate alignment modules."

- DAgger: An imitation learning algorithm (Dataset Aggregation) that iteratively collects corrective labels from an expert during rollouts. "Following a DAgger-like paradigm"

- DDIM sampling: A deterministic sampling method for diffusion models enabling faster inference with few steps. "adopting DDIM sampling~\citep{song2020denoising}"

- Denoiser: The neural network in a diffusion process that predicts (and removes) noise to recover clean data. "with as the denoiser."

- Diffusion model: A generative model that synthesizes data by iteratively denoising from noise (or via flow matching). "a flow-matching based diffusion model, denoted as "

- Diffusion Transformer (DiT): A transformer architecture tailored for diffusion modeling to process and denoise latent sequences. "with DiT "

- Egocentric video: First-person viewpoint video captured from the actor’s perspective. "egocentric videos"

- FID (Fréchet Inception Distance): A metric assessing generative quality by comparing feature distributions of generated and real samples. "R@3, MM Dist, and FID"

- Flow matching: A training objective for generative modeling that learns a velocity field transporting noise to data. "flow-matching based diffusion model"

- Gating network: The component in MoE models that computes mixture weights over expert outputs. "a gating network"

- InfoNCE loss: A contrastive learning objective that pulls positive pairs together and pushes negatives apart. "with InfoNCE loss"

- IsaacGym: A GPU-accelerated physics simulation environment for large-scale RL training. "in the IsaacGym simulation environment"

- Kinematic mimicry: Direct pose-tracking without inferring intent or semantics, often brittle to errors. "kinematic mimicry"

- LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation): A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that adapts large models via low-rank updates. "finetunes the VLM via LoRA~\citep{hu2022lora}"

- Mixture of Experts (MoE): An architecture combining multiple expert subnetworks weighted by a learned gate for improved capacity/generalization. "a Mixture of Experts (MoE) module"

- Motion latent: A compact representation encoding motion dynamics/kinematics used to condition policies or decoders. "motion latents"

- MPJPE (Mean Per Joint Position Error): A metric measuring average 3D joint position error over time. "Mean Per Joint Position Error ($E_{\text{mpjpe}$)"

- MPKPE (Mean Per Keypoint Position Error): A metric measuring average 3D keypoint position error over time. "Mean Per Keypoint Position Error ($E_{\text{mpkpe}$)"

- MuJoCo: A physics engine for simulating articulated bodies and contact dynamics. "cross-simulator transfer (MuJoCo)"

- Proprioceptive state: Internal sensor readings of a robot (e.g., joint positions/velocities, base orientation). "proprioceptive states"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): An on-policy RL algorithm that stabilizes updates via clipped objectives. "using the PPO algorithm~\citep{schulman2017proximal}"

- Reference State Initialization: Initializing episodes from random phases of reference motions to improve tracking robustness. "we adopt the Reference State Initialization framework \cite{peng2018deepmimic}."

- Retargeting: Adapting human motion data to a robot’s morphology/kinematics for execution. "pose estimation and retargeting"

- Self-attention: An attention mechanism over elements within the same sequence to model temporal or structural dependencies. "and self-attention blocks capturing temporal dependencies"

- Sim-to-real: Transferring policies learned in simulation to real-world robots. "sim-to-real gaps"

- SMPL-X: A parametric 3D human body model with expressive hands and face used for motion representation. "with motions formatted as SMPL-X."

- Teleoperation: Real-time remote control of a robot, often mirroring human motions or commands. "teleoperation settings"

- Telepresence: Remote “being there” via a robot that mirrors the operator’s intended actions and perspective. "telepresence via egocentric videos"

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): A latent-variable generative model trained to encode/decode data via a probabilistic bottleneck. "We first train a VAE~\citep{kingma2013auto}"

- Video latent: An embedding capturing semantics/dynamics extracted from video by a VLM. "video latent representation $l_{\text{vlm}$"

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A model that jointly processes visual and textual inputs to produce aligned representations. "We introduce a VLM-assisted locomotion policy"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.