Adaptation of Agentic AI (2512.16301v1)

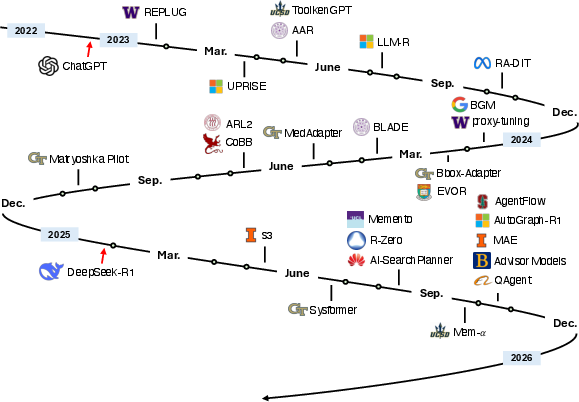

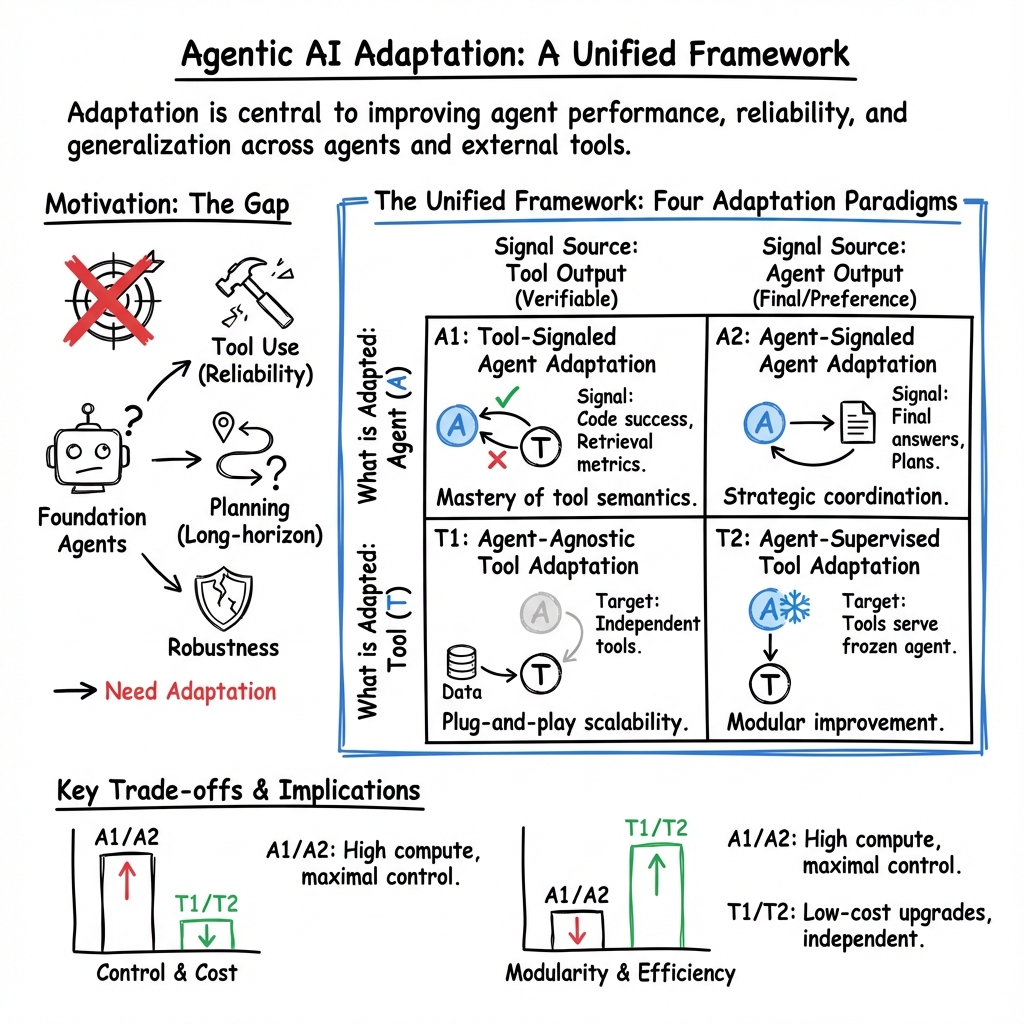

Abstract: Cutting-edge agentic AI systems are built on foundation models that can be adapted to plan, reason, and interact with external tools to perform increasingly complex and specialized tasks. As these systems grow in capability and scope, adaptation becomes a central mechanism for improving performance, reliability, and generalization. In this paper, we unify the rapidly expanding research landscape into a systematic framework that spans both agent adaptations and tool adaptations. We further decompose these into tool-execution-signaled and agent-output-signaled forms of agent adaptation, as well as agent-agnostic and agent-supervised forms of tool adaptation. We demonstrate that this framework helps clarify the design space of adaptation strategies in agentic AI, makes their trade-offs explicit, and provides practical guidance for selecting or switching among strategies during system design. We then review the representative approaches in each category, analyze their strengths and limitations, and highlight key open challenges and future opportunities. Overall, this paper aims to offer a conceptual foundation and practical roadmap for researchers and practitioners seeking to build more capable, efficient, and reliable agentic AI systems.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

1) What this paper is about

This paper is a clear guide to making AI “agents” better at real-world tasks. An AI agent is like a smart helper that can plan steps, use tools (like a web search, a calculator, or a code runner), and remember things to finish complex jobs. The paper explains simple, organized ways to improve either:

- the agent itself (its “brain”), or

- the tools around it (its “toolbox”).

It introduces a four-part framework that shows the main options for adapting agentic AI, compares their pros and cons, and gives practical advice on when to use each one.

2) The big questions the paper answers

The paper focuses on a few easy-to-understand questions:

- How can we systematically improve AI agents and the tools they use?

- What are the main types of adaptation, and how do they differ?

- When should you train the agent vs. when should you upgrade the tools?

- What trade-offs (like cost, flexibility, and reliability) come with each choice?

- How do these ideas apply to real tasks like research, coding, computer use, and drug discovery?

3) How the authors approach it

This is a survey and framework paper. That means the authors:

- Read and organized many recent studies about AI agents.

- Built a simple, unified framework with four categories.

- Explained each category using examples and plain language.

- Compared the categories to help readers pick the right strategy.

Before the framework, they introduce two everyday ways to adapt AI:

- Prompt engineering: changing the agent’s instructions and examples, like giving a better recipe to a cook without changing the cook’s skills.

- Fine-tuning: training the agent so it actually learns new skills, like practice sessions or coaching.

Then they present the four adaptation paths, using a “student and toolbox” analogy:

- A1: Tool-execution–signaled agent adaptation

- What it means: Teach the agent using direct feedback from tools.

- Analogy: A student writes code; a tester runs it. If it passes tests, the student learns “this kind of code works.”

- When useful: You can measure success immediately (e.g., code passes, search result is relevant).

- A2: Agent-output–signaled agent adaptation

- What it means: Teach the agent based on whether the final answer is good, not just whether the tool worked.

- Analogy: The teacher grades the student’s final answer, no matter how they got it.

- When useful: You care about the final result (the answer), even if many tools were involved.

- T1: Agent-agnostic tool adaptation

- What it means: Upgrade the tools independently, without changing the agent.

- Analogy: Buy a better calculator or a smarter search engine. The student stays the same, but their tools improve.

- When useful: The agent is fixed (for example, a closed-source API), and you want plug-and-play tools that help any agent.

- T2: Agent-supervised tool adaptation

- What it means: Improve the tools using feedback from a fixed agent’s behavior.

- Analogy: The student can’t be retrained, but you tune the search engine to return results that this student understands best.

- Special note: The agent’s “memory” is treated as a tool here. The agent’s outputs can update and improve this memory over time.

Two common training styles show up across these categories:

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT): Learn from examples of what good behavior looks like.

- Reinforcement learning (RL): Learn by trial-and-error with rewards for success.

4) What they found and why it matters

The main “results” are a clean map of the design space and practical comparisons, not new experiments. Here are the key insights that matter in practice:

- A simple, four-part framework clarifies choices:

- Adapt the agent (A1/A2) or adapt the tools (T1/T2).

- Use signals from tool outcomes (A1) or from final answers (A2).

- Train tools independently (T1) or using a frozen agent’s feedback (T2).

- Clear trade-offs help you choose:

- Cost vs. flexibility: Training big agents (A1/A2) is powerful but expensive. Training tools (T1/T2) is often cheaper and more modular.

- Generalization: T1 tools trained on broad data often work well across agents and tasks. A1/A2 risk overfitting if not careful.

- Modularity and safety: T2 lets you upgrade tools without touching the agent, reducing risk of “forgetting” old skills.

- Combining strategies often works best:

- Strong systems mix approaches. For example, use a pre-trained retriever (T1), tune a reranker with agent feedback (T2), and fine-tune the agent with execution signals (A1).

- Real application areas:

- Deep research, software development, computer use (e.g., automating apps), and drug discovery all benefit from picking the right adaptation mix.

5) Why this is useful going forward

This framework gives builders and researchers a practical roadmap:

- It helps teams pick the right lever: retrain the agent, upgrade the tools, or both.

- It supports safer, more reliable systems by favoring modular upgrades (especially T2) when changing the agent is risky or costly.

- It points to promising future work:

- Co-adaptation: training agents and tools together in smart ways.

- Continual adaptation: improving over time without forgetting.

- Safe adaptation: avoiding harmful behaviors while learning.

- Efficient adaptation: reducing compute and data costs.

- Better evaluation: shared tests so everyone can compare fairly.

In short, the paper turns a messy, fast-moving field into a simple playbook. If you think of an AI agent as a student with a toolbox, this work tells you when to coach the student, when to buy better tools, and how to get the best results for the least effort.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper’s framework and survey. Each item is phrased to be concrete and actionable for future research.

- Unified, standardized evaluation protocols: Design cross-paradigm benchmarks that measure reliability, generalization, long-horizon planning, and tool-using competence comparably across A1, A2, T1, and T2, including clear attribution of gains to the agent vs. tools.

- Formal theory of adaptation dynamics: Develop convergence, stability, sample-complexity, and generalization analyses for agent adaptation driven by tool-execution signals (A1) and agent-output signals (A2), including off-policy bias, reward misspecification, and distribution-shift effects.

- Credit assignment between agent and tool: Establish principled methods (e.g., bi-level optimization, counterfactual interventions, Shapley-style attribution) to decide whether performance errors should trigger agent updates (A1/A2) or tool updates (T1/T2), especially in multi-step, multi-tool pipelines.

- Strategy selection and switching: Operationalize “selecting or switching among strategies” with concrete meta-learning or bandit controllers that decide, per task or per episode, whether to apply A1, A2, T1, or T2 (or combinations), and evaluate switching policies under resource budgets and latency constraints.

- Co-adaptation algorithms: Propose scalable joint optimization routines for simultaneous agent–tool adaptation (e.g., alternating optimization with stability guarantees, differentiable tool proxies, or coordinated RL) and study their failure modes (feedback loops, oscillations).

- Continual and lifelong adaptation: Develop methods to prevent catastrophic forgetting during repeated A1/A2 fine-tuning; quantify forgetting with standardized metrics; design memory-aware curricula and modular adapters that preserve previously acquired skills.

- Safe adaptation primitives: Create robust reward designs and guardrails that prevent reward hacking, tool misuse (e.g., unsafe code execution), and hallucination amplification during RL; include sandbox isolation protocols, kill-switches, and formal verification where possible.

- Non-stationarity and API drift: Detect and mitigate performance degradation when closed-source agents or external tools update versions; build rapid retuning pipelines and drift monitors for T1/T2 to maintain compatibility with evolving agents.

- Data curation for adaptation signals: Establish best practices for generating or collecting datasets that include verifiable tool outcomes (A1) and high-quality final-answer labels or preferences (A2), with diagnostics for label leakage, spurious correlations, and synthetic data fidelity.

- Reward design for non-verifiable tasks: Extend RLVR-like approaches to domains lacking verifiable execution signals (e.g., web research, planning quality), including calibrated reward models and robust preference aggregation schemes with uncertainty quantification.

- Memory-as-tool design and evaluation: Specify write/read policies, pruning, deduplication, and contradiction handling; introduce retention and utility metrics (e.g., temporal decay curves, retrieval impact on answer correctness) to evaluate T2 memory updates reliably.

- Tool interface learning and standardization: Define schemas (e.g., MCP/API contracts) and learnable tool invocation languages/DSLs that enable agents to compose tools robustly; benchmark how interface design affects adaptation success across paradigms.

- Generalization across domains and environments: Test adaptation methods under tool availability shifts, partial observability, adversarial inputs, and OOD tasks; propose domain-transfer protocols and robustification techniques (e.g., uncertainty-aware planning, OOD detection).

- Scalability and efficiency: Quantify compute/data budgets and cost–performance trade-offs; develop sample-efficient RL and PEFT variants tailored to agentic settings; include latency- and cost-aware objectives for deployment realism.

- Modularity vs. end-to-end trade-offs: Theorize when modular T2/T1 pipelines outperform end-to-end A1/A2 training, and under what data/regime conditions joint training is preferable; provide empirical ablations isolating modularity effects.

- Attribution and diagnostics tooling: Build tooling to trace failures through agent reasoning, tool outputs, and memory retrieval; provide standardized error taxonomies and automated root-cause analysis to guide whether to adapt the agent or the tool.

- Human-in-the-loop signals: Clarify how human preferences, demonstrations, and critiques should be injected into A2 and T2; study scalable preference collection, disagreement resolution, and annotator-effect biases on downstream adaptation.

- Security and privacy in tool use: Evaluate vulnerabilities (e.g., prompt injection, API exploitation, data exfiltration) during adaptation; propose secure tool invocation policies, red-teaming protocols, and privacy-preserving logging for agent-supervised tool training.

- Subagents as tools: Formalize training objectives, communication protocols, and coordination mechanisms for subagent-as-tool setups (T2), including evaluation of division of labor, emergent behaviors, and cross-agent transferability.

- Robustness of retrieval and reranking tools (T1/T2): Investigate overfitting of tools to the supervising agent, cross-agent transfer metrics, and techniques (e.g., domain randomization, adversarial negatives) to maintain portability and avoid brittle coupling.

- Multi-modal extension: Extend the framework beyond text to vision, audio, and embodied interaction; define verifiable signals for multi-modal tools (e.g., simulators), and evaluate adaptation in perception–action loops.

- Benchmarking long-horizon planning: Create canonical tasks and datasets (e.g., software projects, scientific workflows) that quantify planning depth, replanning quality, and tool orchestration efficiency, with clear metrics for intermediate progress and final success.

- Reproducibility and reporting standards: Provide minimal reproducible pipelines, ablation templates that isolate adaptation effects, and reporting checklists (datasets, reward functions, tool interfaces, compute) to enable fair cross-study comparisons.

- Ethical impacts and fairness: Audit how adaptation (especially T2 memory updates and T1 retrievers) might amplify biases; design fairness-aware objectives and post-hoc debiasing tools; include subgroup performance reporting in benchmarks.

- Failure recovery in continual adaptation: Define rollback strategies, checkpointing policies, and online monitoring to detect regressions caused by adaptation; develop safe “undo/repair” procedures for memory writes and tool retuning.

Glossary

- A1: Tool Execution Signaled Agent Adaptation: Agent optimization driven by verifiable outcomes from invoked tools (e.g., execution success, retrieval scores). "A1: Tool Execution Signaled Agent Adaptation (\S \ref{subsub:a1_math}, \S \ref{subsec:tool_execution_signal}): The agent is optimized using verifiable outcomes produced by external tools it invokes."

- A2: Agent Output Signaled Agent Adaptation: Agent optimization guided by evaluations of the agent’s final outputs (answers, plans, traces), possibly after tool use. "A2: Agent Output Signaled Agent Adaptation (\S\ref{subsub:a2_math}, \S\ref{subsec:agent_output_as_signal_for_agent}): The agent is optimized using evaluations of its own outputs, e.g., final answers, plans, or reasoning traces, possibly after incorporating tool results."

- Agent-Agnostic Tool Adaptation: Training tools independently of a fixed agent so they can be plugged into the system. "T1: Agent-Agnostic Tool Adaptation (\S\ref{subsub:t1_math}, \S\ref{subsec:agent_agnostic_tool_training}): Tools are trained independently of the frozen agent."

- Agent-Supervised Tool Adaptation: Adapting tools using signals derived from a frozen agent’s outputs to better support that agent. "T2: Agent-Supervised Tool Adaptation (\S\ref{subsub:t2_math}, \S\ref{subsec:agent_output_as_signal_for_tool}): The agent remains fixed while its tools are adapted using signals derived from the agentâs outputs."

- Agentic AI: Autonomous AI systems that perceive, reason, act, use tools and memory, and execute multi-step plans for complex tasks. "agentic AI systems: autonomous AI systems capable of perceiving their environment, invoking external tools, managing memory, and executing multi-step plans toward completing complex tasks"

- Agentic Memory: Memory systems treated as tools that are updated under agent supervision to enhance future reasoning. "Agentic Memory and Others (\S\ref{subsubsec:4.2.3})"

- Behavior Cloning: Imitation learning that trains a model to reproduce demonstrated behavior via supervised objectives. "such as supervised fine-tuning (SFT) or behavior cloning."

- Catastrophic Forgetting: Loss of previously learned capabilities when adapting to new tasks without safeguards. "A1/A2 methods may suffer from catastrophic forgetting when adapting to new tasks."

- Chain-of-Thought: A static planning technique where models generate step-by-step reasoning to solve tasks. "Static planning methods, such as Chain-of-Thought~\citep{wei2022chain} and Tree-of-Thought~\citep{yao2023tree}, enable structured reasoning through single-path or multi-path task decomposition."

- Co-Adaptation: Jointly adapting agents and tools to improve system performance holistically. "Co-Adaptation (\S\ref{subsec:co-adapt})"

- Contrastive Learning: Representation learning that pulls together positives and pushes apart negatives; common in retrievers/rankers. "such as supervised learning, contrastive learning, or reinforcement learning."

- Continual Adaptation: Ongoing model or tool adaptation over time as new data and interactions accrue. "Continual Adaptation (\S\ref{subsec:continual_adapt})"

- Dense Retrievers: Neural retrieval models that index and search with dense embeddings rather than sparse tokens. "T1-style retrieval tools (pre-trained dense retrievers)"

- Direct Preference Optimization (DPO): A preference-based training method aligning models to human/automated preferences without full RL. "Preference-based methods, such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) \citep{rafailov2023direct} and its extensions \citep{xiao2024comprehensive}, align the model with human or automated preference signals."

- Exact Matching Accuracy: Evaluation metric that scores final outputs based on exact equality with reference answers. "by calculating exact matching accuracy."

- Foundation Models: Large pretrained models that provide general capabilities and can be adapted for specific tasks. "Cutting-edge agentic AI systems are built on foundation models that can be adapted to plan, reason, and interact with external tools"

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): An RL algorithm variant designed for optimizing policies via group-relative signals. "Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) \citep{shao2024deepseekmath}"

- Long-Horizon Planning: Planning over many steps or extended time horizons, often challenging for agents. "limited long-horizon planning"

- Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA): A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that inserts low-rank adapters to update large models cheaply. "low-rank adaptation (LoRA) \citep{hu2022lora}"

- Model Context Protocols (MCPs): Standards/protocols for connecting models to external tools and contexts. "Model Context Protocols (MCPs)"

- nDCG: Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain, a ranking metric evaluating ordered retrieval results. "metrics such as recall or nDCG"

- Off-Policy Methods: RL methods that learn from data generated by a different policy than the one being optimized. "Earlier Works: SFT {paper_content} Off-Policy Methods (\S\subsubsec:3.1.1)"

- Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT): Techniques that adapt large models by updating only small subsets of parameters. "parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, such as low-rank adaptation (LoRA) \citep{hu2022lora}, update only a small subset of parameters."

- Preference-based methods: Training approaches that use preference signals (human or automated) to align model behavior. "Preference-based methods, such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) \citep{rafailov2023direct} and its extensions \citep{xiao2024comprehensive}, align the model with human or automated preference signals."

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A widely used RL algorithm for stable policy updates with clipped objectives. "Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) \citep{schulman2017proximal}"

- Prompt Engineering: Designing prompts and instructions to steer model behavior without changing parameters. "Prompt engineering serves as a lightweight form of adaptation that guides the behavior of an agentic AI system without modifying its underlying model parameters."

- ReAct: A dynamic planning method interleaving reasoning and action using tool/environment feedback. "dynamic planning approaches, such as ReAct~\citep{yao2022react} and Reflexion~\citep{shinn2023reflexion}, incorporate feedback from the environment or past actions"

- Reflexion: A dynamic planning framework where agents reflect on past actions to refine future behavior. "dynamic planning approaches, such as ReAct~\citep{yao2022react} and Reflexion~\citep{shinn2023reflexion}, incorporate feedback from the environment or past actions"

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): Learning by interacting with environments and optimizing behavior via rewards. "The dotted black lines separate the cases of supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning (RL)."

- Reranker: A model/tool that reorders retrieved items to improve relevance before generation. "reward-driven retriever tuning, adaptive rerankers, search subagents, and memory-update modules"

- Retriever: A tool/module that fetches relevant documents or memories for the agent to use. "Tools can include retrievers, planners, executors, simulators, or other computational modules."

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): A paradigm where generation is conditioned on documents retrieved for a given query. "many systems employ retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) mechanisms that retrieve and integrate stored knowledge into the agentâs reasoning process."

- RLVR-Based Methods: Reinforcement learning approaches that leverage verifiable signals/rewards from tool execution. "RLVR-Based Methods (\S\ref{subsubsec:3.1.2})"

- Sandbox: A controlled code execution environment used to safely run generated programs and capture outputs. "The sandbox executes the code and returns an execution result , which the agent may optionally use to generate a final answer ."

- Search Subagents: Specialized agent tools dedicated to search or exploration that support a main (frozen) agent. "reward-driven retriever tuning, adaptive rerankers, search subagents, and memory-update modules trained to better support the frozen agent."

- Subagent-as-Tool: Treating a subordinate agent as a tool that can be trained/adapted to assist the main agent. "Subagent-as-Tool (\S\ref{subsubsec:4.2.2})"

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): Training a model on labeled demonstrations to imitate desired behavior. "Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) \citep{wei2022finetuned} performs imitation learning on curated demonstrations."

- Tree-of-Thought: A static planning technique that explores multiple reasoning paths in a tree structure. "Static planning methods, such as Chain-of-Thought~\citep{wei2022chain} and Tree-of-Thought~\citep{yao2023tree}, enable structured reasoning through single-path or multi-path task decomposition."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable, sector-linked use cases that can be deployed now, drawing directly from the paper’s four adaptation paradigms (A1, A2, T1, T2). Each bullet specifies the application, relevant sector(s), likely tools/products/workflows, and key feasibility dependencies.

- Software engineering (industry): Adaptive code-gen assistant with execution feedback (

A1)- Tools/products/workflows: Code sandbox with unit/integration test harnesses; RLVR/PPO policy optimization over pass/fail signals; prompt+LoRA fine-tuning fallback; automatic tool-call construction for linters, static analyzers, and CI checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safe, deterministic sandboxes; robust test coverage; version control integration; compute budget for RL; guardrails for harmful code.

- Enterprise RAG optimization (industry): Plug-and-play retrievers/rerankers trained independently (

T1) and tuned with agent feedback (T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Retriever/reranker trainers; corpus ingestion pipelines; agent-supervised scoring (weighted data selection, output-consistency training); evaluation harnesses (nDCG/Recall/answer accuracy).

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality, up-to-date corpora; privacy/compliance controls; reproducible evaluation; access to frozen LLM APIs; latency budgets.

- Data analytics and BI (finance, industry): SQL/dataframe agents corrected via execution signals (

A1)- Tools/products/workflows: Query validators; test datasets; RL from execution outcomes (syntax validity, row-count checks); fallbacks to preference-based tuning for final outputs (

A2). - Assumptions/dependencies: Safe database sandboxes; schema discovery; performance isolation; monitoring; human-in-the-loop approval.

- Tools/products/workflows: Query validators; test datasets; RL from execution outcomes (syntax validity, row-count checks); fallbacks to preference-based tuning for final outputs (

- Deep research copilots (academia, industry): Adaptive search and synthesis with final-answer feedback (

A2) and agent-supervised tools (T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Document retrievers; adaptive rerankers; memory modules that store/reuse findings; correctness scoring (exact match, citation validation); cascaded architectures blending

T1retrievers,T2search subagents, andA2answer optimization. - Assumptions/dependencies: Access to scholarly indexes/APIs; automated citation checking; deduplication; hallucination mitigation; domain benchmarks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Document retrievers; adaptive rerankers; memory modules that store/reuse findings; correctness scoring (exact match, citation validation); cascaded architectures blending

- Customer support triage (industry): Agent-supervised knowledge tools (

T2) with frozen LLMs- Tools/products/workflows: Case summarizers; FAQ matchers; adaptive rerankers tuned on agent resolution quality; memory write functions for reusable solutions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clean knowledge base; privacy controls; feedback loops for resolution quality; escalation workflows.

- Compliance/document review (legal, finance, industry): Retrieval-centric agents with agent-agnostic tools (

T1) and output-weighted tuning (T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Regulation corpora; semantic retrievers; risk/rule detectors; agent-derived weights for reranker updates; audit logs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Up-to-date regulatory data; rule-grounding protocols; auditability; human oversight; bias/coverage checks.

- Clinical literature assistant (healthcare, academia): Evidence retrieval and synthesis using

T1retrievers andT2memory- Tools/products/workflows: Medical ontology-aware retrievers; agent-managed memory of key trials; answer verification (PICO extraction, trial-phase checks); prompt engineering guardrails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to medical databases; PHI-safe pipelines; clinical validation; domain ontologies.

- Education/tutoring (education, daily life): Personalized memory and tool adaptation around frozen LLMs (

T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Student profiles; long-term memory stores of misconceptions and progress; adaptive question generators; answer-level reward signals guiding tool updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy for student data; curriculum-aligned evaluation; parental/teacher controls; guardrails on feedback quality.

- Browser and computer-use automation (daily life, industry IT): ReAct/reflexion-style agents with adaptive tools (

T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Headless browser APIs; agent-supervised action models (click/scroll/submit); memory of successful workflows; error recovery heuristics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable DOM/selectors; permissions; sandboxing to prevent harmful actions; logging and rollback.

- Knowledge management/PKM (daily life, industry): Agentic memory as a tool trained via agent outputs (

T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Note/rule extraction; write functions for long-term memory; retrieval policies tuned on success-weighted trajectories; semantic clustering.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear write/read policies; deduplication; privacy; device sync; versioning.

- MLOps and agent ops (software, industry): Adaptation orchestration pipelines selecting

A1/A2/T1/T2per task- Tools/products/workflows: Strategy selection checklists (cost/flexibility/modularity); offline SFT datasets; preference collection interfaces; RL environments with verifiable signals; evaluation dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data pipelines; experiment tracking; governance gates; compute planning; incident response.

- Quant research assistants (finance): Execution-feedback tuned tool use for backtesting and data cleaning (

A1,T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Backtest simulators; metrics-as-rewards (Sharpe, drawdown constraints); agent-supervised data quality filters; hypothesis memory.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensed market data; stable simulators; risk guardrails; compliance review.

Long-Term Applications

The following use cases require further research, scaling, or development—often involving co-adaptation, continual learning, safety guarantees, or complex environments.

- Joint agent–tool co-adaptation platforms (software, industry): Coordinated training of agents and tools (

A1+A2withT2)- Tools/products/workflows: Multi-objective trainers; curriculum scheduling across components; anti-forgetting regularizers; topology-aware orchestration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale compute; unified telemetry; stability controls; robust evaluation suites.

- Continual adaptation in dynamic environments (industry, robotics, healthcare, finance): Lifelong updating under drift and new tasks

- Tools/products/workflows: Data drift detection; safe model update gates; memory consolidation; task-aware adapters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality streams; labeling or weak supervision; rollback mechanisms; legal/compliance oversight.

- Certified safe adaptation (policy, healthcare, finance): Formal guarantees for tool use and updates

- Tools/products/workflows: Verification layers; constrained RL; policy shields; red-teaming and standardized audits; provenance tracking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory standards; test-case corpora; formal methods expertise; independent auditing.

- Embodied agents for robotics and automation (

A1via execution signals,A2for task success): Tool-use with real-world feedback- Tools/products/workflows: Simulation-to-real pipelines; multi-modal tool suites (perception, manipulation); reward shaping from task completion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safety cages; simulators; sensor calibration; robust failure recovery; operator oversight.

- Energy and industrial control (energy, industry): Adaptive agents coordinating tools under simulation rewards (

A1/A2,T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Grid/process simulators; policy optimization over stability/efficiency objectives; agent-supervised anomaly detectors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity simulators; stringent safety thresholds; regulatory approval; cyber-security hardening.

- Drug discovery and lab automation (healthcare, pharma): Multi-agent, tool-rich pipelines with adaptive memory (

T2) and execution feedback (A1)- Tools/products/workflows: Hypothesis generators; assay planning; lab-robot orchestration; memory of experimental outcomes; reward from validated hits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Lab infrastructure; data sharing agreements; long-horizon evaluation; ethics and IP management.

- Autonomous portfolio and risk management (finance): Simulation-based RL with agent-supervised tools

- Tools/products/workflows: Scenario generators; stress-test suites; tool updates driven by final risk/return objectives; continual adaptation under market regimes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory compliance; robust simulators; explainability; capital limits; security.

- Government and regulatory co-pilots (policy): Secure agentic RAG with standardized evaluation and audit trails (

T2)- Tools/products/workflows: Policy corpora; agent-weighted retriever training; long-term memory of rulings; transparent provenance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data licensing; privacy; non-partisan oversight; appeals and human review; resilience against manipulation.

- Personalized, lifelong learning tutors (education): Persistent memory and adaptive tool ecosystems (

T2, futureA2SFT/RL)- Tools/products/workflows: Skill maps; curriculum-aware retrieval; preference learning; cross-course knowledge transfer; long-horizon assessments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consent and privacy; pedagogical validation; fairness; teacher dashboards.

- Standardized evaluation ecosystems (academia, industry, policy): Benchmarks and protocols for adaptation strategies

- Tools/products/workflows: Task suites separating

A1vsA2effects; modular metrics forT1vsT2; cost/flexibility/generalization scorecards; public leaderboards. - Assumptions/dependencies: Community governance; data sharing; reproducibility standards; funding/support.

- Tools/products/workflows: Task suites separating

- Agentic app marketplaces (software, industry): Plug-and-play adaptive tools (retrievers, planners, memory, subagents)

- Tools/products/workflows: MCP-style interfaces; conformance testing; agent-supervised installation; safe update channels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interoperability specs; security vetting; versioning; economic incentives.

- Multi-agent systems with subagent-as-tool (

T2): Specialized subagents trained via frozen main-agent outputs- Tools/products/workflows: Role definitions; negotiation protocols; credit assignment; agent-supervised training of subagents for search, planning, and memory.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coordination frameworks; conflict resolution; performance attribution; monitoring.

Notes on Assumptions and Dependencies Across Applications

- Data quality, privacy, and compliance: Enterprise and regulated sectors require clean, up-to-date, and legally compliant data ingestion and retrieval.

- Access constraints: Many scenarios assume frozen, closed-source LLM APIs; adaptation must focus on tools (

T1,T2) and prompt engineering. - Verifiable signals:

A1depends on reliable execution feedback (tests, simulators, API outcomes);A2needs robust final-output metrics (accuracy, preference scores). - Safety and governance: Guardrails, audits, provenance, and human oversight are critical—especially for healthcare, finance, energy, and policy.

- Compute and observability: RL and co-adaptation demand budgeted compute, experiment tracking, monitoring, and rollback strategies.

- Modularity and interoperability: Tool interfaces (e.g., MCP) and standardized evaluation enable continuous improvement without retraining core agents.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.