CAPE: Capability Achievement via Policy Execution

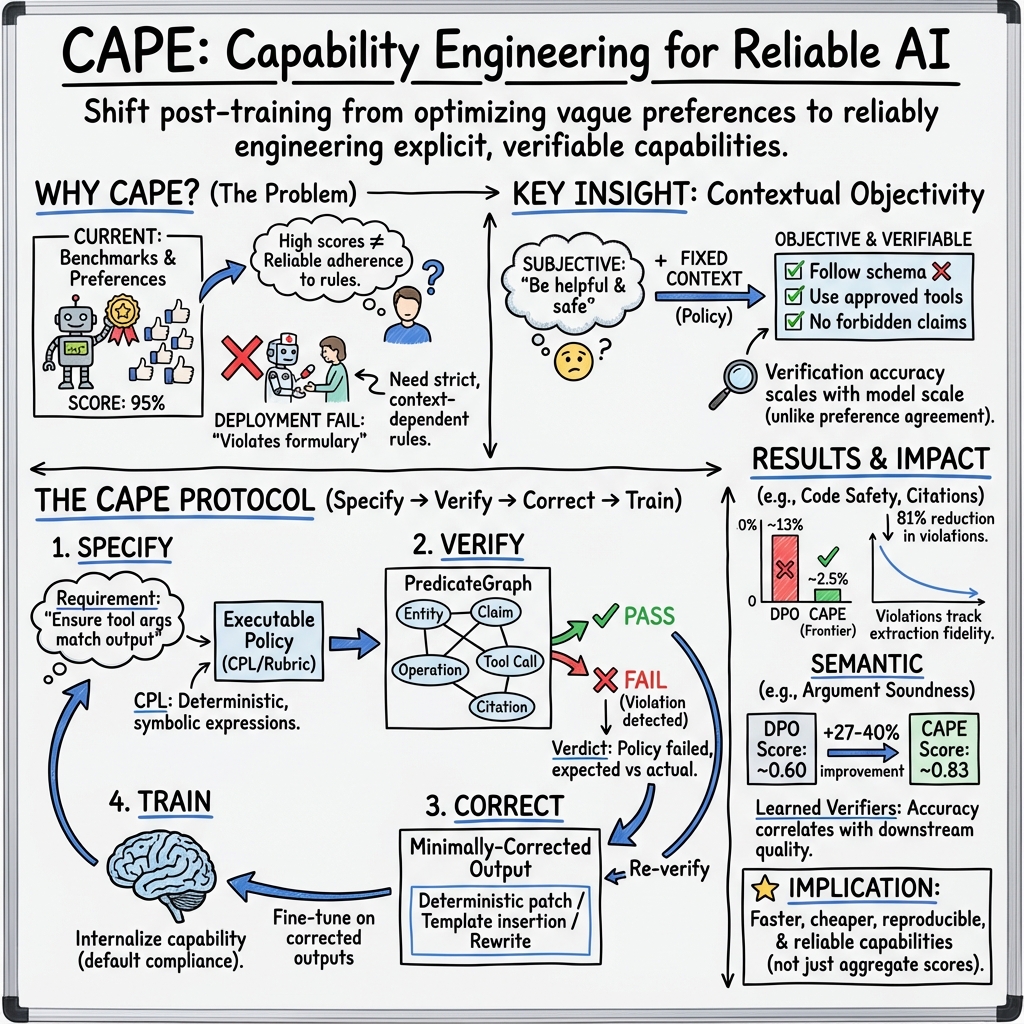

Abstract: Modern AI systems lack a way to express and enforce requirements. Pre-training produces intelligence, and post-training optimizes preferences, but neither guarantees that models reliably satisfy explicit, context-dependent constraints. This missing abstraction explains why highly intelligent models routinely fail in deployment despite strong benchmark performance. We introduce Capability Engineering, the systematic practice of converting requirements into executable specifications and training models to satisfy them by default. We operationalize this practice through CAPE (Capability Achievement via Policy Execution), a protocol implementing a Specify -> Verify -> Correct -> Train loop. CAPE is grounded in two empirical findings: (1) contextual objectivity, where properties appearing subjective become objective once context is fixed (inter-annotator agreement rises from kappa = 0.42 to kappa = 0.98), and (2) verification-fidelity scaling, where verification accuracy improves with model scale (r = 0.94), unlike preference agreement which plateaus at 30 to 50 percent disagreement regardless of compute. Across 109,500 examples in six domains, CAPE reduces violation rates by 81 percent relative to DPO (standard deviation less than 0.3 percent). By replacing per-example annotation with reusable specifications, CAPE reduces costs by 5 to 20 times and shortens timelines from months to weeks. We release the CAPE protocol, PredicateGraph schema, CPL specification language, and policy packs under Apache 2.0. We also launch CapabilityBench, a public registry of model evaluations against community-contributed policies, shifting evaluation from intelligence benchmarks toward capability measurement.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A simple guide to “CAPE: Capability Achievement via Policy Execution”

What this paper is about (the big idea)

This paper says modern AI is smart but not reliably well-behaved. It can answer tough questions, but it often breaks real-world rules (like a hospital’s medication policies or a company’s legal rules). The authors introduce a way to fix that, called CAPE. Think of CAPE like turning “please do the right thing” into clear, checkable rules—then teaching the AI to follow those rules by default.

They call this new practice “Capability Engineering.” It’s like software engineering for AI behavior: you write rules (specifications), test them, fix problems you find, and train the AI so it stops making those mistakes.

What the researchers wanted to find out

The paper focuses on a few easy-to-understand questions:

- Can we turn messy, human instructions (“Be helpful”) into precise, checkable rules (“Cite only from provided documents,” “Use exactly the approved drugs”)?

- If we do that, can we automatically check whether the AI followed the rules and train it to do better every time it breaks one?

- Does rule-checking get more accurate as models get better (so we can keep improving), unlike human preference judgments (which often disagree and don’t improve with more compute)?

- Will this make AIs more reliable, cheaper to train, and faster to deploy?

How the approach works (with simple analogies)

The CAPE method is a loop with four steps: Specify → Verify → Correct → Train.

- Specify: Write the requirement as a clear rule the computer can run. Imagine your teacher’s grading rubric turned into a checklist the computer understands.

- Verify: Automatically check if the AI’s answer follows the rule. Like a referee blowing a whistle if a line is crossed.

- Correct: Fix the specific part that broke the rule. Like a spell-checker for behaviors: it doesn’t rewrite the whole essay—just fixes the mistake.

- Train: Teach the AI using the corrected version so next time it gets it right without help.

To make this work, they use a few tools:

- PredicateGraph: A structured “map” of the AI’s answer. Think of turning a paragraph into a labeled outline: claims, numbers, citations, tool calls, and so on. This makes rules easy to check.

- CPL (CAPE Policy Language): A small, safe rule language. It’s like writing simple math/logic statements—“If you used the calculator, the number you pass to it must equal your computed result.”

- Symbolic policies vs. learned verifiers:

- Symbolic policies are pure rules for things you can check by pattern or structure (e.g., “Every fact must have a citation,” “No use of forbidden functions in code”).

- Learned verifiers are small grading AIs trained on clear rubrics for meaning-based checks (e.g., “Is the reasoning logically valid?”). They’re like trained graders who know what to look for, not just “what they prefer.”

- Meta-verification: A second check that makes sure the first checker didn’t hallucinate a problem. Like a moderator double-checking a referee’s call.

What they tested and why it matters

The authors ran 109,500 examples across six areas, including:

- Arithmetic with tools (e.g., calculator use needs exact numbers)

- Code safety (no dangerous functions)

- Citation grounding (facts must be tied to given sources)

- Reasoning quality, proof validity, and code correctness (checked with rubrics)

They compared CAPE to common methods that learn from human preferences (like DPO and RLHF) and to principle-based methods (like Constitutional AI). Here’s what they found in simple terms:

- Context turns “subjective” into “objective.” When you specify the exact situation, people (and models) agree far more on what’s right. For vague questions like “Is this good medical advice?” humans didn’t agree much. But when the rule was specific (“Only recommend approved drugs and flag contraindications”), agreement shot up—from moderate to almost perfect. That means many “opinions” become facts once you define the context clearly.

- Rule-checking scales with better models. As models get better at following structure and longer contexts, automatic verification gets more accurate. This is different from human preference disagreements (which stay high no matter the compute). So with CAPE, the ceiling moves upward as models improve.

- CAPE reduces rule violations a lot. Across three structural domains, CAPE cut violations by 81% compared to a popular preference-learning method (DPO). In some cases, violations dropped to just a few percent, and for deterministic (rule-only) checks, they were extremely stable.

- It’s cheaper and faster. Instead of labeling every example by hand, you write the rule once and reuse it. The paper reports 5–20x lower costs and moving from “months to weeks” for getting a system production-ready.

- It helps with “meaning” tasks too. For things like reasoning or proof validity, CAPE’s learned verifiers (trained on rubrics) improved scores steadily each training round. The better the verifier, the better the final model. This shows that “verification quality” is the key lever for improvement.

- It avoids known RL pitfalls. Some reinforcement-learning methods accidentally reward longer answers or skew by difficulty. CAPE avoids these “math quirks” because it uses pass/fail checks and targeted fixes, not shaped rewards.

Why these results are important

Here’s why this matters outside of a lab:

- Real-world reliability: Hospitals, banks, and law firms have strict rules. CAPE helps models follow those rules consistently, not just “try to be helpful.”

- Auditability and trust: Rules are written down, checked, versioned, and tied to test results. If something goes wrong, you can see exactly which rule failed and how it was fixed.

- Reuse and speed: One rule can be applied across thousands of examples and multiple projects. That speeds up deployment and lowers ongoing costs.

- Better benchmarks: The authors release CapabilityBench, which tests “can you follow the rules?” rather than just “are you smart on a quiz?” This shifts attention from intelligence to capability—the thing businesses and users actually need.

The bottom line (what this means going forward)

CAPE treats AI behavior like engineering, not guesswork. Instead of relying on human preferences (which often disagree), it turns requirements into clear, executable policies. Then it checks, fixes, and teaches the model until it gets those rules right by default.

- For objective, structural rules (like formatting, citations, or safe code), CAPE delivers very reliable performance.

- For meaning-heavy rules (like reasoning quality), CAPE’s learned verifiers—trained with precise rubrics and double-checked—provide strong, improving signals as models scale.

- Some things will always be subjective (e.g., “beautiful writing”), and those still need preference learning. But most production failures are about rules, not taste—and CAPE targets those directly.

In short: this work shows a practical path to turn “smart AIs” into “reliable AIs” that consistently follow the rules that matter in the real world.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, framed to inform concrete next steps for future research.

- External validity beyond curated tasks: No end-to-end evaluations in high-stakes, regulated deployments (e.g., hospitals, banks) to test CAPE under real-world data drift, governance, and operational constraints.

- Reproducibility and artifacts: Insufficient detail on released code/data for CPL, PredicateGraph extractors, verifiers, and policy packs; unclear seeds, hyperparameters, and full dataset provenance to enable independent replication.

- Causal evidence for the “verification-fidelity scaling law”: Reported high correlations (e.g., r = 0.94) are not supported by causal tests; need controlled interventions that improve verification fidelity while holding other variables constant.

- Reliance on frontier extractors: Best results require “frontier” extraction models; open questions about cost, latency, and feasibility in production and on-device settings when such models are unavailable.

- Generalization to unseen or updated policies: Unclear whether models trained via CAPE can follow novel policies zero-shot or require costly re-training for each policy/version change.

- Policy authoring burden and governance: No quantified analysis of how long it takes non-research teams to write, validate, and maintain robust policies at enterprise scale; missing tooling and processes for review, audit, and approval.

- Coverage and expressivity limits of

CPL: The language is intentionally non–Turing-complete; gaps remain for temporal, probabilistic, or cross-instance constraints and richer dataflow/logical dependencies without sacrificing decidability. - Policy conflict resolution at scale: Deterministic tier/priority rules are described, but scalability with dozens to hundreds of interacting policies, cross-domain dependencies, and dynamic contexts is untested.

- Policy drift and versioning: No methodology for detecting policy obsolescence, managing versioned rollouts, backward compatibility, and automatic re-training schedules as requirements/regulations change.

- Robustness to adversaries and jailbreaks: Compliance rates are reported absent guardrails; no stress-testing against adversarial prompts, output-space attacks, policy injection, or extractor/verifier evasion.

- Goodharting and gaming risks: Insufficient analysis of models exploiting verifier and extractor idiosyncrasies; need adversarial red teaming, randomized audits, and cross-verifier ensembles to mitigate reward hacking.

- Meta-verification reliability: Residual 4% hallucinated issues remain; lack of calibration analysis, confidence intervals, and failure mode taxonomy when verifier and meta-verifier disagree or co-adapt.

- Verifier domain adaptation cost: Learned verifiers require 500–1,000 rubric-labeled examples; unclear annotation burdens across domains/languages and strategies for few-shot or synthetic-data bootstrapping.

- Calibration and thresholds: How to set decision thresholds for learned verifiers (e.g., τ_meta) to balance false positives/negatives under varying risk profiles; missing calibration protocols and guarantees.

- Impact on creative/subjective tasks: CAPE focuses on objective properties; effects on creativity, style, or user satisfaction for tasks with subjective goals are unmeasured.

- Latency and throughput: End-to-end training/inference overheads for extraction, verification, and correction are not quantified; missing SLO-aware deployment strategies and budgeted trade-offs.

- Sequential and long-horizon tasks: No method for verifying stateful, multi-turn workflows with delayed consequences, tool/agent actions, and cross-step constraints over long contexts.

- Multimodal and tool-rich settings: Extension beyond text (vision, audio) and complex tool ecosystems (APIs, databases, actuators) is not evaluated; open design for multimodal PredicateGraphs and policies.

- Safety, fairness, and values: Policies can encode organizational biases; lack of fairness audits, cross-cultural validation, and methods to align or reconcile conflicting stakeholder requirements.

- Baseline strength and compute parity: Details on hyperparameter tuning parity and stronger baselines (e.g., process rewards, verifier-guided RL variants) are limited; frontier extractor usage may confound fairness claims.

- Correction validity beyond “passing policies”: Minimality and semantic fidelity of corrections (especially constrained rewrites) are not audited for downstream task utility or unintended regressions.

- Failure analysis granularity: No detailed taxonomy of residual structural/semantic failures and their frequencies to guide targeted verifier or policy improvements.

- Cross-lingual robustness: CAPE’s behavior across languages and code-switching remains unexplored; policy and verifier portability to non-English contexts is unknown.

- Security of evaluation pipeline: PredicateGraph extraction and

CPLevaluation could be targets for prompt/structure injection; need sandboxing, schema hardening, and integrity checks. - Privacy and compliance: Storing structured traces (PredicateGraphs, violations) may expose sensitive data; privacy-preserving verification and data minimization strategies are unspecified.

- Interaction with RL methods: Open question whether CAPE composes with RLVR/process-based RL to yield additive gains or suffers interference; missing joint ablation studies.

- Verifier drift and co-adaptation: As models learn to pass current verifiers, discriminative power may erode; need holdout policies, rotating verifier ensembles, and periodic re-benchmarking.

- Economic impact claims: Reported 5–20x cost reductions lack a transparent cost model (policy authoring amortization, annotator hours, compute, maintenance) and external validation.

- CapabilityBench governance: How community-contributed policies are vetted for quality, non-maliciousness, and reproducibility; leaderboard design to prevent overfitting to posted policies.

- Theoretical guarantees: Claims of “guaranteed improvement through correction” are empirical; need formal bounds on satisfaction probability for T1/T2 policies and statistical guarantees for learned verifiers (e.g., conformal risk control).

- Distribution shift detection: Mechanisms to detect when verification or correction pipelines become unreliable under domain shift and to trigger human-in-the-loop escalation are unspecified.

Glossary

- Advantage normalization: A training technique that scales or normalizes the policy gradient advantage signal, which can introduce systematic biases (e.g., via length or difficulty normalization). Example: "There is no advantage normalization, no length-based reward shaping, no difficulty weighting."

- Algorithmic bias: Systematic, method-induced distortions in learning behavior caused by properties of the optimization objective rather than implementation bugs. Example: "Beyond preference noise, reward-based methods exhibit structural biases."

- AlphaProof: A system that uses formal proof tooling as a reward signal to train models for theorem proving. Example: "AlphaProof [Hubert et al., 2025] uses formal verification in Lean as reward signal, achieving similar IMO-level results."

- Best-of-N + Filter: An inference-time strategy that generates multiple candidates and selects the first that satisfies all policies. Example: "Best-of-N + Filter: Generate N = 8 candidates, select first passing all policies (inference only, no training)"

- CAPE (Capability Achievement via Policy Execution): A protocol for specification-based post-training that iterates Specify -> Verify -> Correct -> Train to enforce requirements. Example: "CAPE (Capability Achievement via Policy Execution) operationalizes these insights into a closed training loop that sidesteps the algorithmic pathologies of reward-based methods."

- Capability Engineering: The practice of converting requirements into executable specifications and training models to satisfy them by default. Example: "We introduce Capability Engineering, the systematic practice of converting requirements into executable specifications and training models to satisfy them by default."

- CapabilityBench: A public registry for evaluating models against community-written policies to measure capability rather than benchmark intelligence. Example: "CapabilityBench, a public registry of model evaluations against community-contributed policies,"

- Closed correction loop: The CAPE mechanism that fixes detected violations and feeds corrected outputs back into training. Example: "CAPE's contribution is the closed correction loop and reusable specifications"

- Constitutional AI: A method that guides models using natural language principles for self-critique and revision, trained via AI feedback. Example: "Constitutional AI [Bai et al., 2022b] uses natural language principles ('Choose the response that is most helpful, harmless, and honest') for self-critique and revision, training via RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF)."

- Constrained decoding: Generation constrained by formal grammars or schemas to ensure structured, valid outputs. Example: "JSON mode, grammar constraints, and constrained decoding have matured significantly."

- Contextual objectivity: The phenomenon where seemingly subjective properties become objectively verifiable once the context is fully specified. Example: "contextual objectivity, where properties appearing subjective become objective once context is fixed (inter-annotator k rises from 0.42 to 0.98)"

- DPO (Direct Preference Optimization): A preference-based post-training method that optimizes policies directly from preference pairs without a separate reward model. Example: "DPO [Rafailov et al., 2023] simplifies RLHF by eliminating the explicit reward model, directly optimizing policy using a classification objective on preference pairs."

- Dr. GRPO: An algorithmic patch for GRPO intended to mitigate its structural biases. Example: "requiring algorithmic patches like Dr. GRPO [Liu et al., 2025]"

- Extraction fidelity: The accuracy with which outputs are parsed into a structured representation used for verification (e.g., PredicateGraph). Example: "Residual error tracks extraction fidelity."

- Fleiss' kappa: A statistic measuring inter-annotator agreement for categorical ratings across multiple raters. Example: "Fleiss' k = 0.73"

- Formal verification: The use of formal methods and proof assistants to verify correctness against specifications. Example: "uses formal verification in Lean as reward signal"

- Grammar-constrained decoding: A decoding approach that enforces a grammar so outputs adhere to a predefined structure. Example: "Grammar-constrained decoding frameworks have similarly improved"

- GRPO: A reinforcement learning algorithm variant that can suffer from length and difficulty normalization biases. Example: "GRPO suffers from both length bias (dividing advantage by response length) and difficulty-level bias (normalizing by reward standard deviation)"

- Inter-annotator agreement: The degree of consistency among different human annotators assessing the same items. Example: "Inter-annotator agreement study"

- Iterative DPO: A hybrid approach that converts verification pass/fail outcomes into synthetic preference pairs for DPO training. Example: "Iterative DPO: Policy pass/fail converted to synthetic preferences, then standard DPO"

- JSON mode: A structured generation mode that forces the model to emit valid JSON matching a schema. Example: "JSON mode, grammar constraints, and constrained decoding have matured significantly."

- Lean: A formal proof assistant used for mechanized theorem proving and verification. Example: "in Lean as reward signal"

- Learned verifiers: Models trained to evaluate semantic properties using explicit rubrics, producing scores and identified issues. Example: "These are verified by learned verifiers: models trained on explicit rubrics."

- Length bias: A training bias where longer responses are unintentionally favored due to objective normalization. Example: "PPO exhibits length bias"

- Meta-verification: A secondary verification step that checks whether the primary verifier’s identified issues are genuine. Example: "Meta-verification to catch hallucinated issues"

- Outcome RL: A baseline that uses PPO with binary ground-truth rewards on final outcomes rather than process signals. Example: "Outcome RL: PPO [Schulman et al., 2017] with binary ground-truth rewards, clip ratio =0.2"

- Policy RL (dense): An RL baseline that treats policy verdicts as a dense reward vector, one component per policy. Example: "Policy RL (dense): PPO with policy verdicts as reward (one component per policy)"

- Policy tiers (T1/T2/T3): A priority system classifying policies by criticality (objective correctness, safety/governance, structural preferences) and resolving conflicts deterministically. Example: "Policy tiers."

- PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization): A widely used RL algorithm for fine-tuning LLMs via reward signals. Example: "PPO inadvertently favours longer responses due to loss normalization"

- PredicateGraph: A structured intermediate representation of model outputs that exposes entities, claims, operations, tool calls, and citations for policy evaluation. Example: "PredicateGraph schema"

- Preference ceiling: The performance limit imposed by inherent human disagreement in preference data, which additional compute cannot overcome. Example: "The Preference Ceiling."

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): A technique that conditions generation on retrieved external knowledge. Example: "Question-answering with RAG context from Wikipedia."

- RLAIF (Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback): Training that replaces human preference labels with model-generated critiques or preferences. Example: "training via RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF)."

- RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback): A method that trains a reward model from human preferences and optimizes a policy against it. Example: "RLHF [Christiano et al., 2017, Ziegler et al., 2019, Ouyang et al., 2022] trains reward models from human preference comparisons"

- RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards): Reinforcement learning that uses objective, programmatic verification signals as rewards. Example: "RLVR still operates within the reward-shaping paradigm"

- Reward model overoptimization: A failure mode where the proxy reward increases while true quality decreases due to exploiting weaknesses in the reward model. Example: "[Gao et al., 2023] document reward model overoptimization: as training progresses, proxy reward increases while true quality (measured by held-out human evaluation) decreases."

- Soft-scoring methods: Verification approaches that assign graded scores rather than binary pass/fail, useful for free-form tasks. Example: "Soft-scoring methods outperform binary rewards in free-form, unstructured scenarios"

- Structured generation: Techniques that enforce output structure (schemas/grammars) to make outputs reliably parseable. Example: "Structured generation."

- Structured Outputs: A capability to guarantee schema-conformant outputs via model or API features. Example: "Structured Outputs achieves 100%"

- Symbolic policies: Deterministic, code-executed policies that verify structural properties of outputs without interpretation. Example: "CAPE's symbolic policies eliminate interpretation for structural properties."

- Verification-fidelity scaling: The empirical relationship that model performance improves as verification accuracy (and extraction quality) scales with model capability. Example: "Verification-Fidelity Scaling Law"

- Verifier-guided generation and refinement: A training/generation approach where verifier feedback steers solution steps and revisions. Example: "Verifier-guided generation and refinement"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable use cases that can adopt CAPE today, leveraging executable policies (CPL), PredicateGraph-based verification, the Specify → Verify → Correct → Train loop, and the released policy packs and CapabilityBench.

- Healthcare — formulary-locked clinical assistants

- What: LLM copilots that recommend only on-formulary medications, surface contraindications, and follow local clinical protocols by default.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CPL policy packs for formulary inclusion/exclusion and contraindication checks; PredicateGraph entity extraction; tiered policies (T1 correctness for contraindications, T2 governance for formulary); CAPE fine-tuning to reduce violations over time; Capability CI in the EHR integration pipeline.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Up-to-date formulary and contraindication databases; reliable medication/entity extraction; human review for high-stakes cases; organizational approval and logging for audit.

- Finance and Insurance — compliance-bound advisory chatbots

- What: Advisory bots that constrain recommendations to approved product universes, enforce fee disclosures, and verify suitability against stated risk tolerance.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CPL policies for product whitelist/blacklist, mandatory disclosure spans, KYC/AML risk checks; learned verifiers for suitability reasoning; CAPE training to satisfy policies by default; CapabilityBench to certify tasks for procurement.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Current product catalogs and policy libraries; access to client risk profiles; strong claim/citation extraction; compliance sign-off.

- Software Engineering — secure code generation and tool-use correctness

- What: Code copilots that never emit unsafe patterns (e.g., eval, exec, SQL injection), pass required tests, and call tools with exact computed arguments.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CPL policies for banned APIs, input sanitization, required tests; PredicateGraph over code/tool-calls; CI “capability unit tests” step; automatic correction (deterministic patches) then re-verification; fine-tuning with CAPE.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Structured code blocks and tool-call capture; stable schema for PredicateGraph; grammar-constrained decoding for reliability.

- Legal Services — jurisdiction-aware drafting and grounded citations

- What: Research and drafting assistants that cite only provided documents, respect jurisdiction and confidentiality constraints, and adhere to firm style guides.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CPL policies for permitted jurisdictions, mandatory pinpoint citations, redaction/PII; RAG “cite-from-context-only” structural checks; Capability CI dashboards per matter.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate retrieval context; legal entity and citation parsing; firm-specific style policies; privileged data controls.

- Education — rubric-aligned auto-feedback and grading

- What: Tutors and graders that provide structured, rubric-based feedback for proofs, reasoning, and code correctness with issue localization.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Learned verifiers trained on explicit rubrics (reasoning validity, proof completeness, edge-case handling); meta-verification to suppress hallucinated issues; course-specific CapabilityBench suites.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Calibrated rubrics (κ ≥ 0.7); periodic human spot-checks; versioned rubrics across courses.

- Customer Support and CX — SOP-compliant agents

- What: Assistants that reliably follow escalation protocols, sentiment-aware acknowledgment, refund rules, and closure checks.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Tiered CPL policies (T2 governance for refunds/escalations, T3 structural for response flow); CRM-in-the-loop verification; CAPE corrections feeding continuous fine-tuning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Up-to-date SOPs; sentiment/intent detection nodes in PredicateGraph; locale/regulatory variants.

- Enterprise Data and RAG — hallucination-resistant grounded answers

- What: Q&A systems that require every factual claim to be supported by citations drawn from the provided corpus, with format and coverage guarantees.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Structural policies for claim–citation alignment, coverage thresholds, and citation formatting; Best-of-N plus policy-filter inference as a stopgap; CAPE training for default compliance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust claim extraction; high-fidelity structured outputs (JSON/grammar); relevant context retrieval.

- Procurement and Vendor Evaluation — capability certification

- What: Buyers evaluate third-party models against community or org-specific policy packs (e.g., safety, grounding, PII) rather than generic benchmarks.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CapabilityBench integration in RFPs; standard CPL test suites; pass/fail dashboards with traceable failures and fixes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Shared, auditable policy definitions; agreement on tiers and thresholds; evaluator neutrality.

- Data Extraction and Reporting — schema-true structured outputs

- What: Assistants that consistently emit valid JSON/XML matching organization-specific schemas, auto-correcting missing or malformed fields.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Structured generation (grammar/JSON mode); CPL schema conformance checks and deterministic correction; CAPE retraining to internalize schemas.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable schemas and versioning; long-context support for full-output parsing.

- Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) — “compliance-as-code” for AI

- What: Encode safety, privacy, and governance requirements as executable specifications that models learn to satisfy rather than rely on runtime blocking.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Policy repositories (Apache 2.0 policy packs), tiered CPL rulesets for PII, safety, locale laws; Capability CI/CD in MLOps; audit logs of violations and fixes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Organizational policy codification; change-management for updating policies; human override for unresolved semantic policies.

- Product Management and Ops — capability dashboards and triage

- What: Live monitoring of capability violation rates by tier and policy, with auto-generated correction data feeding weekly fine-tunes.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: PredicateGraph extractors; violation analytics; CAPE correction datasets; scheduled CAPE fine-tunes; regression tests in CapabilityBench.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Data infrastructure for logging and storage; compute budget for periodic updates; role ownership (PM/QA).

- Personal Use — constraint-respecting assistants

- What: Personal finance or wellness assistants that respect user policies (budget limits, risk preferences, allergies) by default.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: User-specific CPL policy packs (e.g., exclude peanuts, max daily spend); on-device or cloud verifiers; periodic CAPE adaptation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: User consent and policy authoring UI; private data handling; model support for structured outputs on consumer devices.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases are enabled by CAPE’s verification-first paradigm but require further advances in verifier accuracy, multimodal extraction, standardization, or regulatory acceptance.

- Clinical Decision Support (CDS) with semantic auditors

- What: High-stakes reasoning (diagnosis, treatment plans) verifiably aligned with protocols and evidence, with learned-verifier ensembles checking reasoning validity and coverage.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Multi-verifier committees (reasoning validity, evidence sufficiency, contraindication rationale); human-in-the-loop gates; FDA/EMA-aligned policy packs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Verifier accuracy near expert levels; prospective clinical validation; robust meta-verification; regulatory pathways.

- Autonomous Enterprise Agents — workflow execution with guarantees

- What: Agents that execute multi-step business workflows (e.g., procure-to-pay, claim adjudication) under exact sequencing, permissions, and segregation-of-duties policies.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CPL for step sequencing and RBAC constraints; stateful PredicateGraph spanning multi-turn sessions; CAPE fine-tuning across event logs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable long-context or memory; integration with transaction systems; formalized SOPs; incident response plans.

- Robotics and Industrial Automation — safety and SOP adherence

- What: LLM-driven planners/controllers that comply with safety envelopes, lockout–tagout sequences, and environmental constraints.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Multimodal PredicateGraphs (vision, telemetry); symbolic safety policies; runtime monitors plus CAPE-trained default compliance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-fidelity multimodal extraction; certified runtime safety layers; simulation-to-reality validation.

- Energy and Utilities — policy-constrained operations planning

- What: Grid or plant scheduling/planning assistants that satisfy regulatory, safety, and emissions constraints while optimizing operations.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Policy packs for NERC, emissions caps, and safety checks; learned verifiers for feasibility and contingency reasoning; CapabilityBench for planning tasks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Domain digital twins/simulators for verification; integration with SCADA/EMS; regulator acceptance.

- Legal Reasoning at Scale — filings and analysis with verifiable logic

- What: Drafting and analysis with learned verifiers checking argument soundness, precedent coverage, and jurisdiction fit.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Domain-tuned rubric verifiers (argument validity, completeness); cross-jurisdiction policy libraries; audit trails for liability.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High agreement between verifiers and expert lawyers; standardized legal rubrics; malpractice frameworks for AI-assisted work.

- Market and Regulatory Infrastructure — certification and insurance underwriting

- What: Industry-wide capability certifications and “capability badges” for models; insurers price risk using verified capability profiles instead of generic metrics.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Standardized CapabilityBench suites by sector; third-party policy registries; attestation pipelines with signed policy compliance reports.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Standards bodies (e.g., NIST/ISO) endorsement; independent labs; legal recognition of capability attestations.

- Cross-Domain Semantic Auditors — general-purpose learned verifiers

- What: Compact verifier models acting as plug-in “semantic auditors” for reasoning validity, completeness, and factuality across domains.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Verifier marketplaces; API-based verifier committees; meta-verification services.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust cross-domain generalization; well-calibrated uncertainty; incentives to avoid verifier gaming.

- Fully Automated CAPE-Ops — self-healing capability pipelines

- What: Continuous Specify → Verify → Correct → Train loops that auto-generate correction data, schedule fine-tunes, and promote policy-compliant models with guardrails only as fallback.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Capability CI/CD platforms; policy versioning and impact analysis; drift detection for extraction/verifier fidelity.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: MLOps maturity; compute budgets; organizational governance for promotion criteria.

- Multimodal and Real-World Agents — vision/audio/text constraints

- What: Assistants that follow safety and privacy policies over images/audio (e.g., redact PII in documents/photos; avoid unsafe tool use from voice commands).

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Multimodal PredicateGraph schema; CPL over multimodal predicates; learned verifiers for visual reasoning validity.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-quality multimodal parsing; structured generation beyond text; edge deployment constraints.

- Education and Credentialing — verified mastery and automated assessment

- What: Trusted, scalable evaluation for certifications where verifiers check proof validity, reasoning rigor, and problem-solving completeness across subjects.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Standards-aligned rubrics; proctoring-integrated verification; transparent issue reports for learners.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Verifier reliability parity with expert graders; governance for academic integrity; acceptance by boards/accreditors.

Notes on Feasibility and Adoption

- Technical prerequisites: high-fidelity structured generation (JSON/grammar constraints), long context windows, reliable PredicateGraph extraction, and calibrated learned verifiers with meta-verification for semantic properties.

- Organizational prerequisites: codifying requirements into executable CPL policies and rubrics; integrating Capability CI/CD into existing MLOps/DevOps; role ownership for policy authoring and review.

- Risk management: for high-stakes domains, pair CAPE with human oversight and runtime monitors; maintain audit logs of violations, corrections, and model updates.

- Cost and timelines: CAPE’s reusable specifications can reduce per-task data costs 5–20x and shorten deployment timelines from months to weeks; plan for initial policy authoring effort and subsequent versioning.

- Standards and interoperability: leverage the Apache 2.0 CAPE protocol, PredicateGraph schema, CPL language, and CapabilityBench to promote comparability, compliance, and vendor neutrality across the stack.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.