Any4D: Unified Feed-Forward Metric 4D Reconstruction (2512.10935v1)

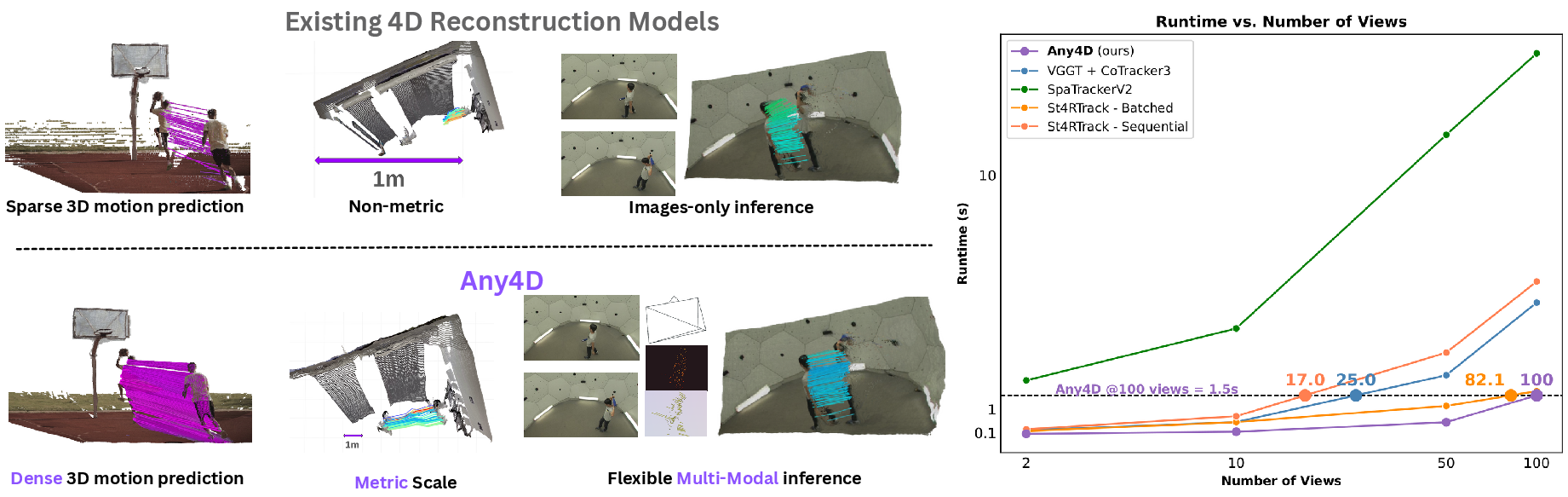

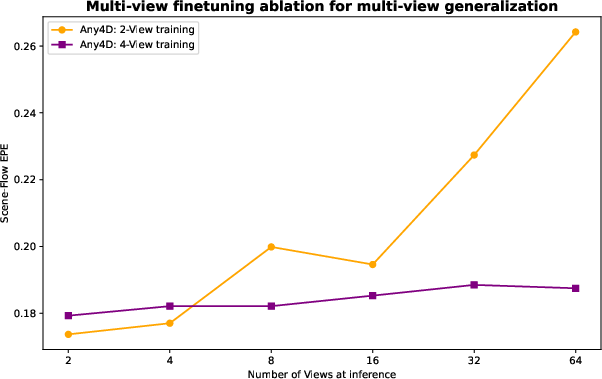

Abstract: We present Any4D, a scalable multi-view transformer for metric-scale, dense feed-forward 4D reconstruction. Any4D directly generates per-pixel motion and geometry predictions for N frames, in contrast to prior work that typically focuses on either 2-view dense scene flow or sparse 3D point tracking. Moreover, unlike other recent methods for 4D reconstruction from monocular RGB videos, Any4D can process additional modalities and sensors such as RGB-D frames, IMU-based egomotion, and Radar Doppler measurements, when available. One of the key innovations that allows for such a flexible framework is a modular representation of a 4D scene; specifically, per-view 4D predictions are encoded using a variety of egocentric factors (depthmaps and camera intrinsics) represented in local camera coordinates, and allocentric factors (camera extrinsics and scene flow) represented in global world coordinates. We achieve superior performance across diverse setups - both in terms of accuracy (2-3X lower error) and compute efficiency (15X faster), opening avenues for multiple downstream applications.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about (overview)

This paper introduces Any4D, a computer vision system that can rebuild a moving 3D scene from video, in real-world units. Think of it like making a 3D “flipbook” of the world where every frame knows exactly where things are and how they move over time. The “4D” means 3D space + time, and “metric” means it measures things in meters, not just in a relative scale.

What the researchers wanted to achieve (key questions)

The team set out to build a single, fast, and flexible model that can:

- Reconstruct the shape of the scene and the motion of everything in it from a few images or video frames.

- Work with different sensors (like RGB cameras, depth cameras, IMUs for motion, and Radar for speed) when available.

- Produce results in real-world units (metric scale), so a robot or AR device knows actual sizes and distances.

- Run in a single pass, fast enough to be useful in real-time applications.

How it works (methods in simple terms)

Picture filming a room or a street with your phone. Any4D takes N frames from that video and, in one go, predicts:

- The 3D shape of everything you see (depth for every pixel).

- How the camera moved between frames.

- How every visible point in the scene moved in 3D (this is called “scene flow,” like tiny arrows showing motion).

To make this work well and flexibly, the model splits the problem into two views of the world:

- Egocentric factors: What each camera sees locally (like per-frame depth and the directions of rays from the camera through each pixel). This is “my view right now.”

- Allocentric factors: A shared world-frame view (like the camera’s position and orientation in the world, and the motion of points in global coordinates). This is “where everything is on the world map.”

Analogy:

- Egocentric is like saying “the door is 2 meters straight ahead of me.”

- Allocentric is like saying “the door is at GPS position X in the building,” so everyone agrees on where it is.

The model uses a multi-view transformer (a powerful neural network that can compare and combine information across multiple frames at once) to process images and optional sensor inputs. It then decodes everything into:

- Per-pixel depth and ray directions (egocentric).

- Per-frame camera pose and per-pixel 3D motion vectors (allocentric).

- A single scene scale, to put everything in meters.

Because the outputs are “factorized” (split into these pieces), the system can learn from many different datasets—even if some only have geometry and others only have motion—by supervising the parts that are available.

What they found (main results and why they matter)

The authors tested Any4D on several benchmarks and compared it to popular methods. Key takeaways:

- Much faster: Up to 15× faster than strong baselines, because it processes all N frames in one feed-forward pass (no slow per-scene optimization loops).

- More accurate:

- Dense 3D motion (scene flow): 2–3× lower errors on average compared to prior methods.

- 3D point tracking: Better at following points in 3D over time, while also predicting motion for every pixel (dense), not just a handful (sparse).

- Video depth: State-of-the-art among single-pass feed-forward methods, and competitive with slower optimization-heavy systems.

- Flexible with sensors: When extra inputs like depth, IMU-based camera motion, or Radar Doppler (speed toward/away from the camera) are available, performance gets even better.

- Best way to represent motion: Predicting motion in the global/world frame (allocentric scene flow) works better than alternatives, leading to cleaner results, especially on object boundaries.

Why this matters:

- Accuracy and speed together are crucial for real-world uses like AR, robots, and advanced video tools. You want detailed, correct, and fast 3D understanding.

Why this is useful (implications and impact)

Because Any4D produces metric, dense 4D reconstructions quickly and can use different sensors, it can help in:

- Robotics: Safer, smarter navigation and manipulation by understanding where things are and how they move.

- AR/VR: More stable, realistic overlays and interactive experiences that sync with the real world.

- Generative AI and video: Better tools for creating, editing, or understanding dynamic 3D content (like animating a moving scene or building 3D assets from video).

A few limitations and what’s next

- The model predicts motion from the first frame to all others, so it works best when important objects are visible in the first frame.

- Sensor inputs (like Radar/IMU) are simulated during training; real sensors can be noisy, and handling that noise is a next step.

- Like any AI model, it improves with more and better training data. More varied dynamic 3D datasets would likely boost performance on very fast or complex motions.

Quick recap

Any4D is a single, fast model that turns a handful of frames (and optional sensor data) into a detailed, metric 4D map of what’s in a scene and how it moves. It’s accurate, flexible, and much faster than previous methods, making it promising for real-world applications in robotics, AR/VR, and creative tools.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future work could address to strengthen and extend the paper’s contributions.

- Real-sensor validation of multi-modal inputs: The model’s claimed support for IMU egomotion and Radar Doppler is only evaluated with simulated signals; no experiments with real, noisy, miscalibrated sensors (e.g., off-the-shelf radars, consumer-grade IMUs, RGB-D cameras) or cross-sensor synchronization and calibration errors are reported.

- Robustness to sensor noise and misalignment: There is no analysis of how measurement noise, latency, calibration drift, or time-stamp jitter in multi-modal inputs affects 4D reconstruction quality and stability.

- Metric-scale claim vs. evaluation with median scaling: Despite predicting a metric scale factor, benchmarks median-scale predictions to align to metric space, obscuring whether the model truly recovers absolute scale without post-hoc normalization; evaluate absolute scale accuracy (e.g., scale error in meters) without rescaling.

- Long-horizon consistency and drift: The model predicts forward allocentric scene flow from the first frame to subsequent frames but does not assess temporal consistency, drift, or cycle-consistency across long sequences or closed loops.

- Handling objects appearing mid-video: Since motion is predicted from the first frame, objects that enter later are not modeled; explore permutation-invariant training/inference and dynamic anchoring that can initialize tracks and motion for late arrivals.

- Occlusions, disocclusions, and re-appearance: There is no evaluation of robustness to long occlusions, disoccluded regions, or re-identification after disappearance; quantify 3D tracking continuity across these events.

- Uncertainty and confidence for motion: The geometry head outputs confidence masks, but the motion head (scene flow) lacks per-pixel uncertainty estimates; add calibrated uncertainty to enable downstream filtering, fusion, and robust planning.

- Pose accuracy and consistency metrics: Camera poses are predicted but not benchmarked explicitly (e.g., translational/rotational errors, relative pose errors across frames, reprojection consistency); include pose accuracy and cross-view consistency evaluations.

- Geometric consistency across outputs: No metrics or analyses verify that predicted depth, intrinsics, poses, and scene flow jointly satisfy reprojection constraints; report geometric residuals (e.g., pointmap reprojection error) and consistency checks.

- Streaming/online inference: The architecture processes N frames jointly in one feed-forward pass; evaluate streaming (sliding window) operation, latency, and stability for real-time robotics or AR where N grows continuously.

- Scalability to high-resolution and many frames: Inference is reported on H100 with up to 64 frames at 518px width; characterize memory, throughput, and accuracy trade-offs for higher resolutions, longer clips (e.g., hundreds of frames), and resource-constrained devices.

- Domain generalization to truly “in the wild” videos: Most motion supervision comes from synthetic data; provide evaluations on diverse, handheld, unconstrained videos with significant camera shake, blur, lighting changes, and complex dynamics (people, animals, thin structures).

- Non-rigid and articulated motion quality: Although Dynamic Replica is included, there is limited analysis of performance on strongly non-rigid scenes (e.g., human bodies, cloth, fluids); add targeted benchmarks and qualitative/quantitative failure analyses.

- Instance-level motion segmentation: Motion masks are derived by thresholding scene flow; investigate explicit instance segmentation of moving objects, object-wise motion consistency, and how motion segmentation quality affects downstream tasks.

- Radar Doppler modeling and fusion: Doppler is simulated as the radial component of egocentric scene flow; assess how real radar artifacts (multipath, occlusions, clutter) impact performance and whether learned fusion mitigates them.

- IMU usage beyond static conditioning: The paper encodes poses via MLPs but does not explore integrating raw IMU streams (accelerations, gyros) for online motion priors or gravity alignment; paper principled inertial-visual fusion in the transformer.

- Calibration and synchronization handling: The method assumes clean inputs; develop and evaluate modules for automatic cross-modal calibration refinement and time alignment during inference.

- Learning without privileged labels: Training uses partial supervision and synthetic ground truth; investigate self-supervised or weakly supervised objectives to learn scene flow and metric scale from raw videos (e.g., photometric, cycle-consistency, epipolar, inertial priors).

- Sensitivity to first-view anchoring: The world frame is anchored to the first view; quantify how the choice of reference frame impacts reconstruction quality and whether adaptive or global (e.g., gravity-aligned) frames improve results.

- Generalization to wide-baseline, low frame-rate inputs: The paper notes potential weaknesses on wide baselines and highly dynamic scenes; systematically test performance and explore curriculum or dataset augmentation strategies to close the gap.

- Motion representation beyond per-frame flow: Allocentric scene flow is predicted per target frame relative to the first; consider learning continuous-time motion fields, enforcing temporal smoothness, and modeling accelerations for better physical plausibility.

- Reconstructing occluded/hidden geometry: The outputs are per-view pointmaps; explore volumetric or layered representations that can reconstruct surfaces not visible in every frame (e.g., behind moving objects).

- Downstream task validation: Claims of utility for robotics and generative applications are not validated; run closed-loop control or video-generation tasks to quantify benefits (e.g., MPC performance, temporal coherence in synthesis).

- Fairness and breadth of baselines: Some baselines require multiple passes or different inputs; broaden comparisons to recent unified feed-forward 4D methods and report sensitivity to their optimal settings to ensure fairness.

- Training curriculum and modality dropout strategy: Multi-modal conditioning probabilities (0.7 overall, 0.5 per modality dropout) are fixed; explore scheduling and adaptive curriculum to optimize joint learning and robustness to missing modalities.

- Rotational representation and normalization: Quaternions are supervised with a sign-agnostic loss, but it’s unclear if unit-norm constraints are enforced; assess numerical stability and explore alternatives (e.g., Lie algebra, 6D rotation) with ablations.

- Evaluation of static vs. dynamic point tracking: Benchmarks emphasize dynamic points; report performance on static point tracks to understand tracking stability and background consistency.

- Energy and deployability: Runtime is measured on H100; report energy usage, batch size sensitivity, and deployability on edge hardware (e.g., Jetson, mobile GPUs) for practical applications.

Glossary

- Allocentric: Refers to representing scene attributes in a global world coordinate frame. "allocentric factors (camera extrinsics and scene flow) represented in global world coordinates."

- Allocentric scene flow: 3D motion vectors predicted in a global coordinate frame. "Allocentric Scene Flow: Directly predicting ."

- Alternating-attention transformer: A transformer design that alternates attention across views to aggregate multi-view information. "Any is a N-view transformer, consisting of modality-specific encoders, followed by an alternating-attention transformer to produce contextual patch embeddings."

- APD: Average percent of points within a spatial delta; a metric for 3D accuracy. "We report average percent of points within delta for 3D points after motion () and inlier percentage $for scene flow." - **Backprojected 2D Flow**: Covisible scene flow obtained by unprojecting optical flow using geometry. "Backprojected 2D Flow: Unprojecting optical flow to obtain covisible scene flow between pointmaps." - **Camera extrinsics**: Parameters defining a camera’s pose in a world coordinate frame. "allocentric factors (camera extrinsics and scene flow) represented in global world coordinates." - **Camera intrinsics**: Parameters describing a camera’s internal geometry (e.g., focal length) used to form ray directions. "egocentric factors (depthmaps and camera intrinsics) represented in local camera coordinates," - **Dense Prediction Transformer (DPT)**: A transformer head for dense per-pixel predictions such as depth and flow. "We use a dense prediction transformer (DPT) \cite{ranftl2021vision} head to predict per-view ray directions $\tilde{R}_i\tilde{D}_i$, and confidence masks." - **DINOv2**: A vision transformer backbone used to encode images into patch-level features. "DINOv2~\cite{oquab2023dinov2} for encoding images, to extract the layer-normalized patch-level features from the final layer of DINOv2 ViT-Large, $F_\text{I} \in \mathbb{R}^{1024 \times H/14 \times W/14}\tilde{F}_\text{ego}$, and using estimated geometry to recover allocentric motion as:" - **Egomotion**: The motion of the camera itself, often measured via IMU. "RGB-D frames, IMU-based egomotion, and Radar Doppler measurements," - **End-Point Error (EPE)**: The Euclidean distance between predicted and ground-truth vectors/points. "We also report End Point Error (EPE) for 3D points after motion (dynamic points) and 3D scene flow vectors." - **Feed-forward**: Inference performed in a single forward pass without iterative optimization. "Any is a transformer that takes flexible multi-modal inputs and outputs a dense metric-scale 4D reconstruction in a single feed-forward pass." - **Flash Attention**: An efficient attention implementation that reduces memory and computation. "and also employ Flash Attention~\cite{dao2023flashattention} for efficiency." - **Forward scene flow**: Motion vectors from a reference view to subsequent views. "scale-normalized forward scene flow from the first view to all other views, i.e., $\tilde{F}_i \in R^{3 \times H \times W}\text{APD} for scene flow."

- Median-scaling: Rescaling predictions to metric space using the median of ratios or distances. "Following \cite{feng2025st4rtrack}, we first perform median-scaling to align to metric space."

- Metric scaling factor: A global scalar that converts scale-normalized predictions to metric coordinates. "Predictions include a metric scaling factor for the entire scene,"

- Metric-scale: Physical units (e.g., meters) rather than arbitrary normalized scale. "metric-scale, dense feed-forward 4D reconstruction."

- Monocular RGB videos: Single-camera color video streams used for 4D reconstruction. "Moreover, unlike other recent methods for 4D reconstruction from monocular RGB videos, Any can process additional modalities"

- Multi-modal: Incorporating diverse sensor inputs (e.g., depth, IMU, RADAR) alongside images. "Any is a transformer that takes flexible multi-modal inputs"

- Multi-view transformer: A transformer that jointly processes tokens from multiple synchronized views. "Any largely follows a multi-view transformer architecture, similar to \cite{keetha2025mapanything} (see \cref{fig:architecture})."

- N-view transformer: A transformer that processes N input frames jointly. "Any is a N-view transformer, consisting of modality-specific encoders,"

- Optical flow: 2D motion field in the image plane; projection of 3D scene flow. "Any optical flow then is the perspective projection of scene flow onto the camera plane."

- Pointmap: A dense 3D representation where each pixel maps to a 3D point. "in the form of pointmaps~\cite{Wang_2024_CVPR}"

- Quaternion: A 4D rotation parameterization used for camera pose. "represented using a scale-normalized translation vector and quaternion."

- Ray depths: Depth values measured along camera rays from each pixel. "scale-normalized depth along the rays for each view, i.e., ."

- Ray directions: Per-pixel 3D ray vectors derived from camera intrinsics. "ray directions for each view, i.e., "

- RoPE (Rotary Positional Encoding): Positional encoding technique for transformers. "we choose to not use 2-D rotary positional encoding (RoPE) for the inputs,"

- Scale-invariant: Losses or supervision that are independent of absolute metric scale. "Similarly, scene flow is also supervised in a scale-invariant manner."

- Scene flow: The dense 3D motion field of surfaces in a scene. "Scene flow was introduced in~\cite{vedula1999three} as the problem of recovering the 3D motion vector field for every point on every surface observed in a scene."

- Simultaneous Location and Mapping (SLAM): Estimating camera pose and building a map from sequential observations. "It has been studied as Simultaneous Location and Mapping (SLAM)~\cite{mur2017orb, klein2007parallel, engel2014lsd, dellaert2017factor, sharma2021compositional, keetha2024splatam} when visual observations occur in a temporal sequence,"

- Stop-gradient: An operation that prevents backpropagation through a variable. "where denotes the stop-gradient operation and prevents the scale supervision from affecting other predicted quantities."

- Structure-from-motion (SFM): Recovering 3D structure and camera motion from multiple images. "and as structure-from-motion (SFM)~\cite{schonberger2016structure, agarwal2009buildingrome, seitz2006comparison, triggs1999bundle} otherwise."

- Up-to-scale: Quantities predicted modulo an unknown global scale factor. "predicts per-view, up-to-scale translations and quaternions ."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete use cases that can be deployed now with reasonable engineering effort, leveraging Any4D’s feed‑forward, metric‑scale, dense 4D reconstruction and multi‑modal inputs.

- Dense dynamic obstacle maps for planning and control — sectors: robotics, autonomous vehicles (AV), drones

- Application: Provide dense allocentric scene flow (per‑point 3D velocities) and depth to build dynamic occupancy/velocity grids for model predictive control, collision avoidance, and trajectory optimization in cluttered, moving environments.

- Tools/workflows: Any4D ROS2 node that publishes per-frame pointmaps, camera poses, and scene flow; fusion into voxel grids (e.g., TSDF + velocity fields), then fed to planners (e.g., MPC, RRT*, MPPI).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Calibrated camera; frame-to-frame object visibility from the first frame; timing sync if using IMU/Radar; performance measured on high-end GPUs—embedded inference may require pruning/quantization.

- Real-time camera solve and matchmove in dynamic scenes — sectors: media/VFX, software

- Application: Recover global camera extrinsics/intrinsics and dense motion to automate camera tracking and object tracking in footage with moving cameras and moving actors/objects, reducing manual rotoscoping.

- Tools/workflows: Video plug-in for Nuke/After Effects/Premiere; export camera rigs and tracked point clouds; flow-thresholded masks for motion mattes.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Sufficient parallax/texture; stable metric scale if IMU/depth is absent may require scale alignment; high-res frames may need tiling.

- AR occlusion and physics-aware rendering from monocular video — sectors: AR/VR, mobile software

- Application: Use metric depth + allocentric flow to produce high-quality occlusion, contact shadows, and rigid/non-rigid interaction in AR without LiDAR.

- Tools/workflows: Unity/Unreal plug-in consuming Any4D outputs; dynamic collision meshes updated per-frame from pointmaps; motion masks from scene flow thresholds.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Mobile deployment may require distilled models; accurate occlusion depends on motion visibility from the first frame and camera pose stability.

- Multi-modal perception fusion (RGB + IMU + Radar Doppler) — sectors: AV, robotics, smart infrastructure

- Application: Improve motion estimation robustness in low light or adverse weather using optional IMU poses and Doppler velocity conditioning.

- Tools/workflows: Sensor fusion back-end that supplies Any4D with synchronized IMU/pose and Doppler; downstream object trackers receive dense allocentric flow for association.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Precise extrinsic calibration; the paper simulates Doppler—real sensors require noise and bias modeling.

- Dataset annotation acceleration for 3D motion and tracking — sectors: data/labeling, AV/robotics, academia

- Application: Bootstrap labels for 3D tracks, camera poses, depth, motion masks; reduce manual annotation cost for dynamic scene datasets.

- Tools/workflows: Batch inference on raw video; QA tools to accept/refine tracks; export to COCO-like 4D formats.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Domain shift may require light finetuning; moving objects entering after frame 0 may need sliding-window inference.

- Dynamic NeRF/Gaussian Splatting initialization — sectors: graphics, research, games

- Application: Initialize dynamic radiance fields or dynamic Gaussian Splatting with Any4D’s metric depth, poses, and allocentric scene flow to cut training time and improve temporal consistency.

- Tools/workflows: Precompute per-frame point clouds and flow; initialize per-point velocity fields or time-dependent deformation graphs.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Temporal coverage and visibility from frame 0; quality of initialization depends on texture and motion diversity.

- Video depth for editing, relighting, and refocusing — sectors: media/software, creative tools

- Application: Feed-forward video-consistent depth enables depth-aware effects (refocus, fog, relight, parallax) with fewer artifacts.

- Tools/workflows: NLE or compositor plug-in exporting per-frame depth; consistency checks using flow; edge-aware post-processing for matting.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Challenging in textureless regions and specular surfaces; may need scale normalization across shots.

- Onboard mapping for inspection and surveying in dynamic sites — sectors: construction/AEC, energy, public safety

- Application: Drones/UGVs produce metric pointmaps and flow to separate moving machinery/people from static infrastructure, enabling safer autonomous navigation and progress tracking.

- Tools/workflows: ROS2 + GIS pipeline; semantic post-processing to tag dynamic agents; weekly snapshots compared via 4D alignment.

- Dependencies/assumptions: GNSS-denied environments benefit from IMU inputs; safety-critical operation requires tested failure modes.

- Sports and biomechanics analytics — sectors: sports tech, healthcare-adjacent research

- Application: Camera-only 3D motion fields for athletes without markers; derive kinematics, speed maps, ball trajectories in stadium broadcasts.

- Tools/workflows: Broadcast pipeline integration; calibrate broadcast cameras for metric scale (or use field dimensions as priors); export 3D tracks.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Occlusions and crowd motion complicate tracking; multiple viewpoints improve robustness.

- 4D-aware video understanding research — sectors: academia, software

- Application: Use Any4D outputs as supervision or features for action recognition, affordance learning, forecasting (e.g., future flow), and scene graph dynamics.

- Tools/workflows: PyTorch API; plug into training loops as auxiliary targets; benchmark with LSFOdyssey/Replica/Kubric-style splits.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Beware of synthetic-to-real gaps; consider curriculum with real-world finetuning.

- Privacy-preserving motion detection at the edge — sectors: security/surveillance, smart buildings

- Application: Replace RGB storage with ephemeral dense flow + low-res geometry for occupancy and motion statistics without storing identifiable textures.

- Tools/workflows: On-device inference; log aggregated motion fields; policy hooks to drop raw frames post-inference.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Policy and compliance review; edge compute constraints.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases are high-impact but require further research, scaling, robustification, or regulatory approvals before wide deployment.

- Real-time 4D reconstruction on mobile SoCs and AR glasses — sectors: consumer electronics, AR/VR

- Application: Persistent, metric‑scale 4D world models for occlusion, physics, and shared multi-user AR experiences on wearables.

- Tools/workflows: Model compression/distillation; hardware acceleration (NPU); multi-sensor fusion (ToF/IMU/Eye-tracking).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Power/thermal budgets; robust operation under severe sensor noise and motion blur; on-device privacy.

- Cooperative 4D perception for V2X and smart cities — sectors: AV, infrastructure, policy

- Application: Vehicles and roadside units share partial 4D fields (geometry + velocities) to predict hazards and optimize traffic flow.

- Tools/workflows: Standardized 4D scene-flow messages; edge/cloud aggregation; spatiotemporal data fusion.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Communications latency, security; cross-vendor calibration standards; policy on data sharing and retention.

- Surgical AR and real-time intraoperative 4D guidance — sectors: healthcare

- Application: Dense 4D reconstruction in endoscopic or microscope views to compensate tissue motion/deformation for navigation and tool tracking.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-specific training on medical imagery; integration with surgical robots; regulatory-grade validation.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Stringent accuracy, latency, and reliability; sterilizable sensors; FDA/CE approval pathways.

- High-fidelity telepresence and holographic conferencing — sectors: telecom, enterprise collaboration

- Application: Monocular or multi-camera, multi-modal 4D capture streams to reconstruct remote participants as dynamic, metric avatars in real time.

- Tools/workflows: Edge inference with cloud aggregation; compression of dynamic point clouds/flow; rendering in VR/AR.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Bandwidth and latency constraints; privacy controls; multi-view synchronization standards.

- 4D‑aware generative AI and content creation — sectors: media, gaming, creative tools

- Application: Condition or constrain video/gen‑4D models with physically consistent geometry and motion; auto-rigging and simulation-aware content generation.

- Tools/workflows: Training pipelines that ingest Any4D outputs as priors/constraints; differentiable renderers; scene graph dynamics.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Scalable training data with accurate 4D labels; handling of non-Lambertian/transparent materials.

- Standardization and benchmarks for metric 4D datasets — sectors: policy, academia, industry consortia

- Application: Establish shared 4D schemas (geometry, poses, allocentric flow, scale), sensor metadata, and evaluation protocols across domains.

- Tools/workflows: Open benchmarks with dynamic scenes beyond synthetic; protocols for multi-modal synchronization and calibration reporting.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Cross-industry participation; privacy-preserving dataset curation; licensing harmonization.

- Construction robotics with predictive human–robot interaction — sectors: construction/AEC, robotics

- Application: Robots that work near humans using dense velocity fields to forecast motion and plan safe, efficient manipulation and navigation.

- Tools/workflows: Integration with safety-certified planners; continuous 4D mapping of active sites; human intent models layered on flow fields.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Certification and safety cases; robustness in dust/lighting extremes; multi-sensor redundancy.

- Environmental monitoring and disaster response — sectors: public safety, government, NGOs

- Application: Rapid 4D mapping of floods, fires, landslides with drones; estimate flow of debris/water; plan safe routes for responders.

- Tools/workflows: Multi-platform capture (UAS, bodycams, vehicle cams); cloud aggregation; change detection from 4D deltas.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Harsh conditions; intermittent connectivity; data governance and cross-agency coordination.

- Consumer 4D capture and life-logging — sectors: consumer apps, social media

- Application: Turn short handheld videos into metric, dynamic 3D memories; free-viewpoint playback and editing.

- Tools/workflows: Mobile app with on-device or cloud inference; export to USDZ/GLB with motion; privacy-by-design controls.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Efficient inference and battery constraints; user consent and bystander privacy; handling fast motion/blur.

- Predictive digital twins for factories and warehouses — sectors: manufacturing, logistics

- Application: Live 4D twins combining geometry and flow to optimize pathing, detect bottlenecks, and simulate “what-if” scenarios.

- Tools/workflows: Persistent mapping with stationary cameras + mobile robots; flow-driven agent simulation; dashboards for operations.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Camera placement for coverage; calibration maintenance; integration with MES/WMS systems.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- First-frame anchoring: Scene flow is computed from a reference (first) frame; objects entering later require sliding-window or permutation-invariant training to avoid missed tracks.

- Sensor realism: Reported Doppler/IMU benefits are trained with simulated inputs; real deployments need noise/bias models, calibration, and synchronization.

- Domain shift: Accuracy may drop in highly dynamic, low-texture, reflective, or extreme lighting conditions; targeted finetuning or multi-modal inputs can mitigate.

- Compute and latency: Reported speed-ups use data center GPUs (e.g., H100). Mobile/edge deployment will need compression, mixed-precision, and possibly smaller backbones.

- Metric scale: While Any4D predicts metric scale, absolute scaling is stronger with auxiliary sensors; in image-only modes, scale sanity checks or external priors may be necessary.

- Privacy, safety, and compliance: 4D reconstructions of people and places invoke privacy regulations; safety-critical uses (AV, healthcare, construction) require formal validation and certification.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.