Flux4D: Flow-based Unsupervised 4D Reconstruction (2512.03210v1)

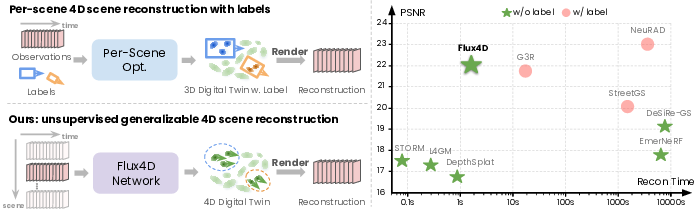

Abstract: Reconstructing large-scale dynamic scenes from visual observations is a fundamental challenge in computer vision, with critical implications for robotics and autonomous systems. While recent differentiable rendering methods such as Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) have achieved impressive photorealistic reconstruction, they suffer from scalability limitations and require annotations to decouple actor motion. Existing self-supervised methods attempt to eliminate explicit annotations by leveraging motion cues and geometric priors, yet they remain constrained by per-scene optimization and sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning. In this paper, we introduce Flux4D, a simple and scalable framework for 4D reconstruction of large-scale dynamic scenes. Flux4D directly predicts 3D Gaussians and their motion dynamics to reconstruct sensor observations in a fully unsupervised manner. By adopting only photometric losses and enforcing an "as static as possible" regularization, Flux4D learns to decompose dynamic elements directly from raw data without requiring pre-trained supervised models or foundational priors simply by training across many scenes. Our approach enables efficient reconstruction of dynamic scenes within seconds, scales effectively to large datasets, and generalizes well to unseen environments, including rare and unknown objects. Experiments on outdoor driving datasets show Flux4D significantly outperforms existing methods in scalability, generalization, and reconstruction quality.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces Flux4D, a new way to build a moving 3D world (like a street with cars and people) directly from raw camera videos and laser scans, without needing human labels. It can quickly reconstruct what the scene looks like and how things move over time, so you can view it from new angles, predict what will happen next, and even edit the scene for simulation.

In short: Flux4D learns a 4D world (3D space + time) from real driving data, fast and at scale, without any manual labeling.

Key Objectives

The research aims to:

- Reconstruct large, real-world driving scenes in 3D over time (4D) using only raw sensors (cameras and LiDAR), and do it quickly.

- Automatically separate what is static (roads, buildings) from what is moving (cars, pedestrians) without human-provided labels.

- Create a general method that works across many different places and still handles new, unseen environments well.

- Render realistic images and depth from new viewpoints and estimate accurate motion (how and where things move).

Methods and Approach

Think of Flux4D as building a “living” 3D model of a street, then animating it to match what cameras saw.

Inputs: What data it uses

- Camera images: what the scene looks like.

- LiDAR point clouds: laser measurements of distance, which give accurate 3D structure.

Scene representation: Tiny 3D “paint blobs”

Flux4D represents the world using many small, fuzzy, colored dots in 3D called “3D Gaussians.” You can imagine them as tiny, semi-transparent paint blobs placed in space:

- Each blob has a position (where it is), size, color, and opacity.

- Flux4D adds a velocity (a 3D arrow) to each blob, capturing how it moves over time.

Three main steps

Here is a simple summary of the process:

- Step 1: Initialize the 3D blobs using LiDAR points and color them using the camera images. This gives a first guess of the scene.

- Step 2: Use a neural network to predict how each blob should move (its velocity) and refine its appearance.

- Step 3: Render the scene at different times and viewpoints (like taking a virtual photo) and compare those images to the real camera images. The network learns by adjusting itself until the virtual images look like the real ones.

How the learning works

- “Photometric loss”: This just means Flux4D tries to make the rendered images match the real photos as closely as possible.

- “As static as possible” rule: The system prefers blobs to stay still unless the data clearly shows they are moving (like a car). This helps separate moving things from the background automatically.

- Training across many scenes: Instead of tuning each scene for hours, Flux4D trains on lots of different scenes so it learns good general rules. This is a big reason it scales and works on new places.

Motion model and refinements

- Motion: The paper mainly uses a simple constant-velocity idea (each blob keeps the same speed and direction over short times), which works well for driving scenes over around 1 second. They also explore slightly more complex motion (like acceleration) with polynomials for better realism.

- Iterative refinement: After an initial pass, Flux4D uses feedback to polish details (sharper edges, better colors), especially where the first guess was rough due to occlusions.

Main Findings

The authors tested Flux4D on real driving datasets (PandaSet and Waymo Open Dataset) and found:

- Better reconstruction quality than previous unsupervised methods: Flux4D produces clearer images, more accurate depth, and cleaner separation between moving and static parts.

- Fast and scalable: It reconstructs scenes in seconds, handles high-resolution images (Full HD and higher), and can use many views (over 60) at once.

- Strong generalization: Even on new, unseen environments—including rare objects—Flux4D performs well because it learns from diverse scenes.

- Accurate motion flow: It estimates how actors move (direction and speed) more reliably than prior label-free methods, and matches or beats specialized scene-flow systems on many metrics.

- Future prediction: It can predict what the scene looks like a few frames ahead (like a “next-frame” guess) and outperforms both unsupervised and some supervised baselines, showing it truly understands the scene over time.

- Simulation and editing: Because the 3D model is explicit and interpretable, you can remove, add, or move objects and re-render realistic camera views—useful for training robots or testing self-driving systems.

Why is this important? It means we can build rich, realistic, editable 4D worlds from raw sensor data—without costly labels—and do it fast enough to scale to huge datasets.

Implications and Impact

Flux4D points to a future where:

- We can create large, realistic, and controllable virtual worlds for robotics and self-driving simulation quickly and cheaply.

- Unsupervised learning (no labels) becomes a powerful way to handle motion and complexity in real-world scenes, especially when trained on diverse data.

- Researchers and engineers can rely on a simple, scalable framework to reconstruct and understand dynamic environments, predict future frames, and edit scenes for testing and training.

Limitations still exist (very complex motions are hard; long sequences can show small glitches at boundaries; assumptions about clean sensors and simple camera models), but the approach lays strong groundwork. Overall, Flux4D shows that simple rules + lots of diverse data can unlock high-quality, fast, and general 4D reconstruction—without needing human annotations.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, targeted at guiding future research.

- Motion model expressiveness: The core formulation assumes constant (or low-order polynomial) per-Gaussian translational velocity with fixed orientation/scale; it does not model rotations, articulated/non-rigid motion, time-varying orientation/scale/opacity, or piecewise motion (birth/death), which limits accuracy for pedestrians, cyclists, turning vehicles, and deformable objects.

- Actor-level dynamics: There is no explicit grouping of Gaussians into instances nor rigid-body constraints (e.g., shared SE(3) parameters per actor). How to induce instance-level motion, joint acceleration/steering, and physical consistency remains open.

- Occlusion/disocclusion handling: The initialization and rendering pipeline does not explicitly reason about occlusions, disocclusions, and visibility changes over time, potentially causing errors when actors enter/exit the field of view or when LiDAR misses surfaces. Methods for temporally coherent visibility are not explored.

- Long-horizon continuity: Reconstruction across long sequences is performed by iterative 1-second snippets and exhibits “transition” artifacts. A unified temporal representation (e.g., recurrent/continuous-time model) that preserves global spatiotemporal consistency over minutes remains to be developed and evaluated.

- Sensor modeling gaps: The method assumes a pinhole camera and clean, synchronized LiDAR; robustness to rolling shutter, motion blur, time-asynchrony, calibration drift, multi-camera synchronization issues, and LiDAR noise is unaddressed.

- Multi-camera scaling: Experiments mainly use a single front camera (PandaSet) or three front cameras (WOD). How the approach scales to full 360° multi-camera rigs (6–12 cameras), large baselines, and cross-camera temporal offsets is not quantified.

- LiDAR-free training: While a LiDAR-free inference mode using monocular depth is shown, the model is trained with LiDAR. End-to-end training without LiDAR, resilience to monocular depth errors, and domain shift across scenes and sensors remain open.

- Ground-truth for dynamic regions and “V_RMSE”: The paper reports dynamic-only metrics and velocity RMSE, but does not clearly specify how dynamic masks are obtained and what ground truth velocities are used. A transparent, reproducible protocol for evaluating motion (e.g., using official tracklets or scene flow correspondences) is needed.

- Rare/unknown object generalization: Claims of generalization to rare and unknown objects are not quantitatively validated (e.g., per-class performance on rare categories, OOD objects, unusual motions). A benchmark for rare dynamic actors is missing.

- Adverse conditions: Robustness to night, rain, fog, lens artifacts, and sensor degradation is untested. How photometric/depth supervision behaves under adverse weather and lighting is unknown.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity and training stability: Despite emphasizing simplicity, sensitivity to loss weights (e.g., velocity regularization/reweighting), Gaussian counts, voxelization, and network depth is not systematically studied across datasets.

- Gaussian resource management: There is no strategy for adaptive Gaussian birth/death, pruning, or memory scheduling in large scenes. How representation size scales and how to manage long sequences without drift or bloat is unresolved.

- Instance extraction pipeline: The paper demonstrates instance manipulation but does not detail how instances are automatically extracted from Gaussians without semantics. A robust, label-free instance grouping method is needed.

- Uncertainty quantification: The model produces deterministic velocities and geometry. Methods to estimate and calibrate uncertainty (per-Gaussian flow/appearance confidence) for safe downstream use are unexplored.

- Physics/semantic priors: The “as static as possible” prior can suppress genuine small motions or misclassify parked vehicles/temporarily stationary actors. Integrating lightweight physics or learned semantic priors without supervision remains an open design problem.

- Joint pose estimation: The approach assumes known, accurate ego-poses. Jointly refining camera/LiDAR poses and 4D scene parameters (bundle adjustment in 4D) could improve consistency but is not attempted.

- Real-time streaming: Although reconstruction is fast per snippet, online, low-latency streaming reconstruction with incremental updates and bounded memory is not addressed.

- Sky/far-background modeling: The use of random points on a spherical plane for sky/far regions is ad hoc. Physically consistent sky/light probes or environment maps and their temporal stability are not investigated.

- Loss design trade-offs: Flow-magnitude reweighting improves dynamic regions but may bias training away from static fidelity. Principled multi-objective balancing and curriculum strategies are not explored.

- Evaluation breadth: Perceptual metrics (LPIPS) are only reported on WOD; human studies and trajectory-level consistency metrics are missing. Novel path rendering (camera trajectories not seen during training) is not systematically evaluated.

- Polynomial motion details: The polynomial motion enhancement lacks specifics (order, parameterization, regularization, failure modes). Comparative analysis versus piecewise-linear or spline motion and actor-level models is needed.

- Small fast-moving actors: Bucketed scene flow errors are still high for pedestrians/wheeled VRUs. Dedicated mechanisms for small, fast-moving objects (e.g., higher sampling density, attention to small regions) are not proposed.

- Appearance changes: Photometric losses assume brightness constancy; specularities, shadows, reflections, and dynamic lighting are not explicitly modeled, potentially limiting fidelity under real-world illumination changes.

- High-resolution rendering artifacts: Anti-aliasing, transparency handling, and Gaussian blending at 1080p+ are not deeply analyzed. Strategies for reducing aliasing and improving thin structures are missing.

- Reproducibility of dynamic-only masks and scene-flow protocol: Exact procedures and code for dynamic region masks, correspondence generation, and scene-flow evaluation (especially on WOD) should be clarified to ensure replicability.

- Data scaling laws: While a scaling trend is shown, quantitative analysis of sample efficiency (performance vs. number of scenes), diminishing returns, and cross-dataset transfer is not provided.

- Integration with world models: The connection to unsupervised world models is conceptual; closed-loop prediction, planning-aware generation, and multi-step consistency (beyond 1–8 s) remain unexplored.

- Multi-modal fusion beyond LiDAR/camera: Radar, event cameras, thermal, and IMU could aid robustness and motion estimation; how to fuse these modalities into Flux4D’s representation is an open direction.

Glossary

- 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS): A differentiable rendering technique that represents scenes with 3D Gaussian primitives for efficient, photorealistic view synthesis. "3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS)~\cite{3dgs}"

- 3D Gaussians: Parametric 3D primitives (position, scale, orientation, color, opacity) used to model scene geometry and appearance. "Flux4D directly predicts 3D Gaussians and their motion dynamics"

- 3D tracklets: Temporally linked 3D detections that track moving actors across frames. "using human annotations such as 3D tracklets or dynamic masks"

- 3D U-Net: A 3D convolutional encoder–decoder architecture with skip connections for volumetric data. "We adopt a 3D U-Net with sparse convolutions~\cite{tangandyang2023torchsparse}"

- : Accuracy metric for scene flow; fraction of points with endpoint error ≤ 10 cm. " and (fraction of points with error 5/10 cm)"

- : Accuracy metric for scene flow; fraction of points with endpoint error ≤ 5 cm. " and (fraction of points with error 5/10 cm)"

- Angular error: The angular difference (in radians) between predicted and ground-truth motion vectors. "angular error in radians ()"

- Autoregressive models: Sequence models that predict future states by conditioning on past outputs. "processed by autoregressive or diffusion-based models to predict future states"

- Bucketed normalized EPE: Endpoint error normalized and evaluated per semantic bucket/class. "bucketed normalized EPE~\cite{khatri2024can}"

- Constant velocity assumption: Modeling motion with a fixed velocity over short time horizons. "This formulation enables continuous, temporally consistent reconstruction under a constant velocity assumption."

- Cycle consistency: A regularization enforcing consistent forward–backward mappings across frames. "cycle consistency \cite{yang2023emernerf}"

- Deformation fields: Spatial transformations that deform a canonical scene to capture dynamics. "use deformation fields~\cite{pumarola2021d,park2020deformable,yang2024deformable,wu20244d} to model dynamic scenes"

- Differentiable rasterization: Rendering of primitives in a way that supports gradient backpropagation. "render the scene using differentiable rasterization~\cite{3dgs}"

- Differentiable rendering: Rendering approaches that allow gradient-based optimization through the image formation process. "differentiable rendering methods such as NeRF and 3DGS"

- EPE3D: 3D endpoint error; measures the magnitude of scene-flow prediction errors. "EPE3D, and "

- Feed-forward neural networks: Models that predict representations directly in a single pass without per-scene optimization. "use feed-forward neural networks to predict scene representations directly from observations"

- Foundation models: Large pre-trained models providing semantic features or priors for downstream tasks. "leverage foundation models for additional semantic features or priors"

- Generalizable methods: Approaches that infer scene representations from observations without per-scene optimization. "Generalizable methods infer scene representations directly from observations without per-scene optimization"

- Geometric constraints: Priors or losses based on geometric relationships used to regularize reconstruction. "geometric constraints \cite{peng2024desire}"

- Iterative refinement: A procedure that progressively improves reconstruction using feedback (e.g., gradients). "we introduce an iterative refinement mechanism inspired by G3R~\cite{chen2025g3r}"

- LiDAR: Light Detection and Ranging; a sensor producing 3D point clouds of the environment. "LiDAR data, commonly available in the autonomous driving domain"

- LPIPS: Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity; a perceptual image similarity metric. "LPIPS"

- Monocular depth estimation: Predicting depth from a single camera image. "monocular depth estimation model~\cite{hu2024metric3d}"

- Motion dynamics: The temporal evolution (e.g., velocity) of scene elements. "3D Gaussians and their motion dynamics"

- Neural Radiance Field (NeRF): A neural volumetric rendering model representing scenes via radiance and density fields. "Neural Radiance Field (NeRF)~\cite{mildenhall2020nerf}"

- Novel view synthesis: Rendering images from viewpoints not present in the input observations. "Novel view synthesis on PandaSet:"

- Photometric losses: Image-space losses (e.g., L1, SSIM) comparing rendered outputs to observations. "employs only photometric losses"

- Pinhole camera model: An idealized perspective projection model for cameras. "the method assumes a simple pinhole camera model"

- Polynomial motion parameterizations: Modeling motion with higher-order polynomials to capture acceleration and turning. "We further introduce polynomial motion parameterizations"

- PSNR: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio; an image fidelity metric comparing signal strength to reconstruction error. "PSNR"

- Scene flow: The 3D motion field of points between consecutive frames. "scene flow estimation"

- Sparse convolutions: Convolution operations optimized for sparse spatial data (e.g., point clouds). "with sparse convolutions~\cite{tangandyang2023torchsparse}"

- Static-preference prior: A regularization favoring minimal motion to avoid unnecessary dynamics. "a simple static-preference prior"

- Structural Similarity (SSIM): A perceptual metric assessing image similarity based on structure, luminance, and contrast. "SSIM"

- Three-way EPE: Endpoint error evaluated separately for background-static, foreground-static, and foreground-dynamic regions. "three-way EPE~\cite{chodosh2024re}: background-static (BS), foreground-static (FS), and foreground-dynamic (FD)"

- Tokenization: Converting visual data into discrete or continuous tokens for sequence modeling. "tokenize visual data into discrete or continuous representations"

- Velocity regularization: A loss term penalizing motion magnitudes to encourage stability. "serves as a velocity regularization term that minimizes motion magnitudes"

- Velocity RMSE (V_RMSE): Root-mean-squared error of predicted velocities/motion. "velocity RMSE (V$_{\mathrm{RMSE}$"

- World models: Unsupervised models that learn predictive representations of environments over time. "unsupervised world models"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a curated list of actionable applications that can be deployed with the paper’s current capabilities (unsupervised, seconds-level reconstruction, high-resolution multi-view rendering, scene flow prediction, and LiDAR-free variant).

- Autonomous driving simulation asset creation and scenario editing — Sector: robotics/automotive, software

- Tools/workflows: use Flux4D to turn raw fleet data (camera + LiDAR) into editable 4D assets; build scenario libraries with actor insertion/removal, trajectory manipulation, and controllable camera paths for training and validation; integrate with existing simulators.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accurate sensor calibration and poses; short time horizons (≈1s) and constant-velocity motion suffice; stable pinhole camera model; diverse training data to cover edge cases; GPU availability for feed-forward inference.

- Label-free decomposition for training data pipelines — Sector: software/ML, robotics/automotive

- Tools/workflows: automatically extract dynamic actor masks, 3D Gaussians, scene flow, and per-actor velocities to reduce manual annotation cost; pre-filter training data (e.g., detect mislabeled frames, noisy segments); generate pseudo-labels for motion-aware tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: sufficient scene diversity for robust unsupervised decomposition; QC safeguards to catch rare failure modes (e.g., complex motion patterns).

- Novel-view rendering for camera/rig design and sensor placement studies — Sector: automotive hardware, robotics

- Tools/workflows: render high-resolution views at new extrinsics to evaluate camera coverage, blind spots, lens choices, and rig configurations before physical deployment.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable extrinsic/intrinsic models; LiDAR or monocular depth-based initialization; reconstruction works best in outdoor driving domains.

- Short-horizon future prediction baseline for forecasting — Sector: robotics/automotive, research

- Tools/workflows: use Flux4D’s next-frame prediction as a baseline for motion forecasting models; generate counterfactuals by editing actor velocities and rerendering to test planner robustness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accuracy degrades over longer horizons with constant-velocity assumption; benefits from velocity reweighting in dynamic regions.

- HD map refresh and static/dynamic separation — Sector: mapping, automotive

- Tools/workflows: update static background layers (roads, buildings) by removing dynamic actors detected via “as static as possible” regularization; fill occluded areas through multi-view fusion and rendering.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable static/dynamic disentanglement; trained on local domain data; batch/offline processing preferred.

- Incident/accident reconstruction for insurance and forensics — Sector: insurance, public safety

- Tools/workflows: reconstruct event scenes from dashcam + LiDAR logs; render novel viewpoints for analysts; compute scene flow and trajectories to support claims or investigations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: chain-of-custody and metadata integrity; sensor calibration and timestamp accuracy; policy compliance on privacy.

- Data augmentation for perception model training — Sector: software/ML

- Tools/workflows: generate novel viewpoints and slight motion counterfactuals for detection/tracking/segmentation training; improve robustness via domain randomization using editable 3D Gaussians.

- Assumptions/dependencies: ensure photometric realism is sufficient for downstream tasks; monitor for distribution shifts introduced by edits.

- Warehouse and campus robot pilots (with multi-sensor rigs) — Sector: robotics (industrial, service)

- Tools/workflows: apply Flux4D to short, multi-sensor indoor/outdoor runs for route validation and scenario rehearsal where LiDAR is available; synthesize views for operator training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: adaptation to indoor lighting and geometries; domain-specific training; performance depends on sensor quality and scene diversity.

- Scene flow estimation in research benchmarks — Sector: academia

- Tools/workflows: use Flux4D as a strong unsupervised baseline for scene flow tasks; provide motion fields for downstream segmentation/forecasting studies; evaluate bucketed class-specific errors as in PandaSet/WOD protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: evaluation restricted to camera FoV; short-horizon consistency; pinhole camera assumption.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, improved motion models, or robustness to sensor imperfections and longer time horizons.

- Real-time onboard 4D reconstruction to support planning and perception — Sector: robotics/automotive

- Tools/products: on-vehicle Flux4D service for continuous reconstruction, dynamic actor tracking, occlusion-aware scene understanding; plug-in to planners and prediction stacks.

- Dependencies: low-latency inference; advanced motion parameterizations beyond constant velocity (acceleration/turning models); resilience to rolling shutter and noisy inputs; hardware acceleration.

- City-scale dynamic digital twins and urban analytics — Sector: smart cities, urban planning, transportation policy

- Tools/products: continuously updated, interpretable 4D models for traffic engineering, capacity planning, and road safety analyses; counterfactual simulations for interventions (e.g., lane changes, signal timing).

- Dependencies: privacy and data governance; heterogeneous sensor fusion across fleets; scalable storage/compute; long-horizon temporal consistency.

- Label-free HD map generation/updating pipelines — Sector: mapping, automotive

- Tools/products: automated workflows that filter dynamics in unlabeled fleet data to maintain high-fidelity static maps; change detection and incremental updates.

- Dependencies: seamless long-term reconstruction; robust static/dynamic decomposition across weather and time-of-day; calibration drift handling.

- Foundation world models with explicit 3D structure — Sector: software/ML, robotics

- Tools/products: integrate Flux4D’s 3D Gaussians and motion fields into generative, predictive world models for planning, policy learning, and simulation; closed-loop training with planners.

- Dependencies: better temporal models (polynomial or learned dynamics); differentiable planners; curriculum training across diverse scenes; scalable iterative refinement.

- Cross-domain deployment (mining, construction, logistics, agriculture) — Sector: industrial robotics

- Tools/products: heavy-equipment operation rehearsal, safety training, and site planning via unsupervised reconstruction of dynamic work zones.

- Dependencies: domain-specific retraining; sensor stacks may differ (sparser LiDAR, stereo); handling dust, occlusions, non-rigid motions.

- Consumer AR/VR “drive-to-experience” with mobile-only sensors — Sector: entertainment, daily life

- Tools/products: smartphone capture → monocular-depth Flux4D → immersive 4D scenes; user-driven camera paths and actor retiming for storytelling.

- Dependencies: reliable monocular metric depth; mobile compute or efficient cloud inference; privacy-preserving pipelines; generalization beyond driving scenes.

- Safety certification and regulatory benchmarking for AVs — Sector: policy/regulation

- Tools/products: standard test suites using unsupervised, editable 4D reconstructions to evaluate perception/planning under realistic, rare, or counterfactual scenarios; evidence generation for compliance audits.

- Dependencies: accepted standards, verifiable fidelity metrics, auditable provenance; alignment with regulatory bodies.

- Infrastructure monitoring and traffic-energy planning — Sector: energy/transport, public sector

- Tools/products: dynamic reconstruction to model traffic flows, idling hotspots, and emissions proxies; simulate impacts of infrastructure changes.

- Dependencies: aggregate multi-source data; long-term consistency; environmental and privacy safeguards.

- Insurance risk modeling and claims acceleration — Sector: finance/insurance

- Tools/products: scenario replay with editable actors for risk scoring; automated triaging using scene flow and reconstruction confidence; fraud detection via multi-view consistency checks.

- Dependencies: vetted evidentiary standards; fairness and bias assessments; secure data custody.

- Cinematic previsualization and VFX — Sector: media/entertainment

- Tools/products: convert location scouts (drive-throughs) into controllable 4D sets; retime actor motion; place virtual cameras and lighting; blend with traditional CG.

- Dependencies: DCC tool integration (USD, NLEs), artist controls for Gaussians, higher-fidelity appearance models for film quality.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies that affect feasibility

- Sensor assumptions: best performance with calibrated multi-view cameras and LiDAR; monocular mode is viable but depends on reliable metric depth estimation.

- Motion modeling: current constant-velocity works well for short horizons; long-term deployments need higher-order or learned dynamics and better occlusion handling.

- Computational constraints: training across many scenes improves decomposition; production systems require efficient GPU/accelerator deployment for real-time or city-scale use.

- Robustness: handling rolling shutter, sensor noise, and domain shifts (weather, lighting) will be necessary for broad adoption.

- Data governance: privacy, anonymization, and policy compliance are critical for fleet-scale data use and public-sector applications.

- Interoperability: integration with simulators, mapping stacks, planners, and creative tools requires standardized formats (e.g., USD, OpenDRIVE) and APIs.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.