Turbo-Muon: Accelerating Orthogonality-Based Optimization with Pre-Conditioning (2512.04632v1)

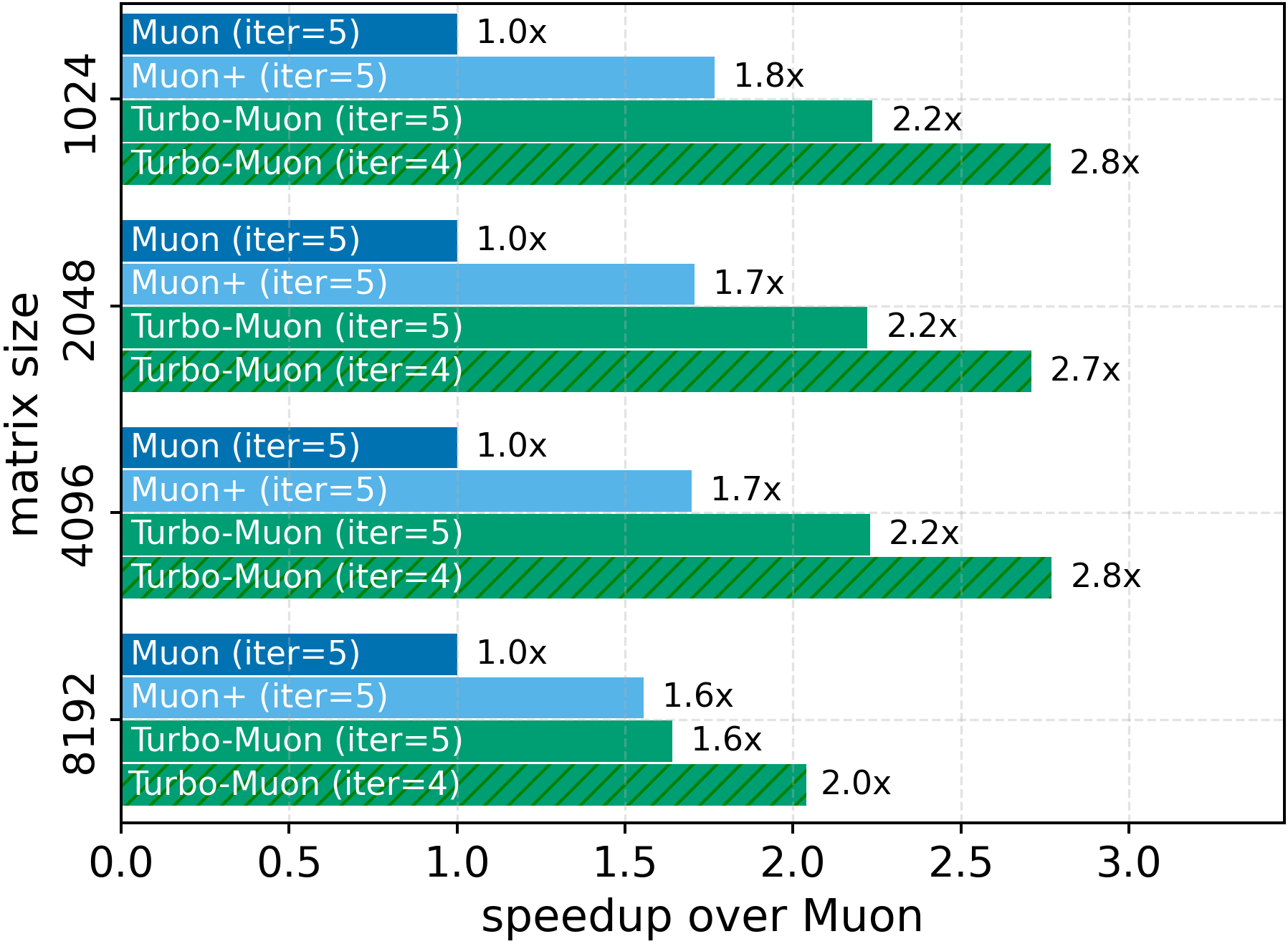

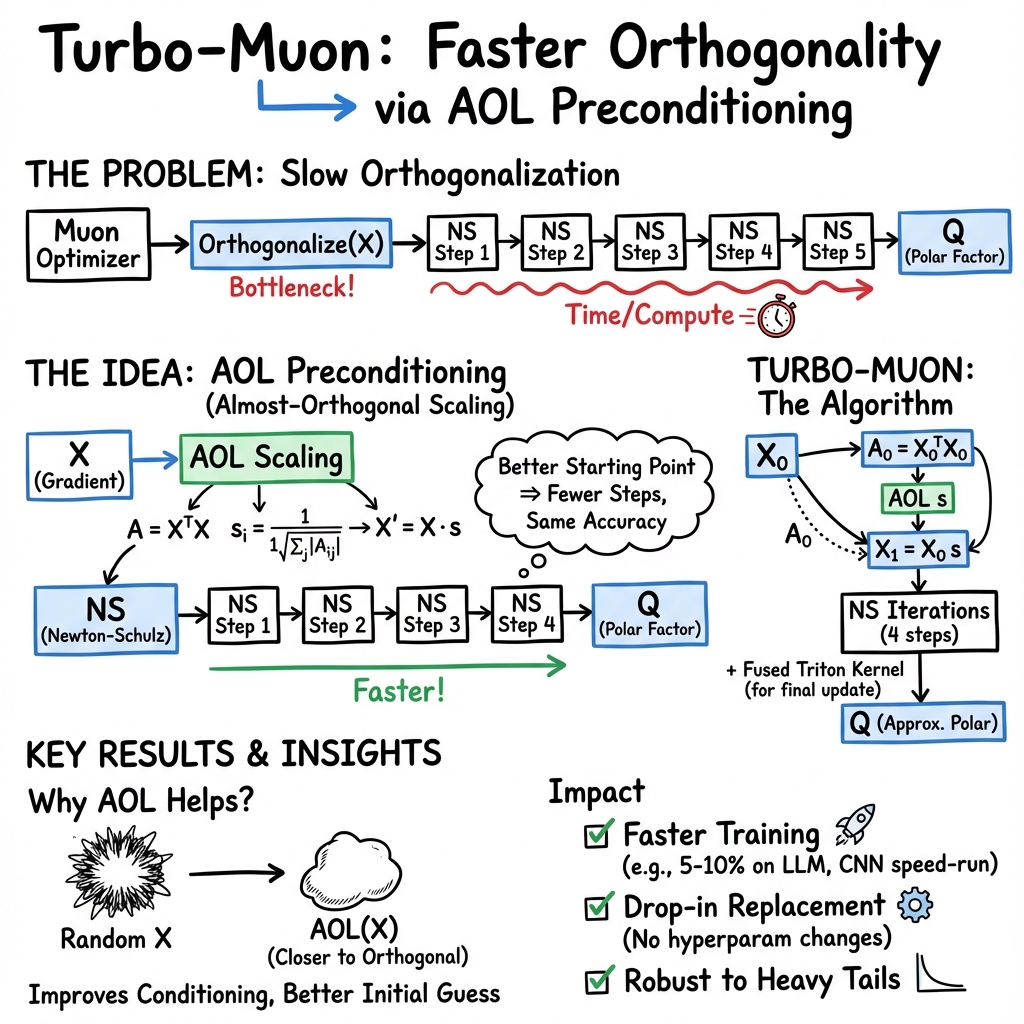

Abstract: Orthogonality-based optimizers, such as Muon, have recently shown strong performance across large-scale training and community-driven efficiency challenges. However, these methods rely on a costly gradient orthogonalization step. Even efficient iterative approximations such as Newton-Schulz remain expensive, typically requiring dozens of matrix multiplications to converge. We introduce a preconditioning procedure that accelerates Newton-Schulz convergence and reduces its computational cost. We evaluate its impact and show that the overhead of our preconditioning can be made negligible. Furthermore, the faster convergence it enables allows us to remove one iteration out of the usual five without degrading approximation quality. Our publicly available implementation achieves up to a 2.8x speedup in the Newton-Schulz approximation. We also show that this has a direct impact on end-to-end training runtime with 5-10% improvement in realistic training scenarios across two efficiency-focused tasks. On challenging language or vision tasks, we validate that our method maintains equal or superior model performance while improving runtime. Crucially, these improvements require no hyperparameter tuning and can be adopted as a simple drop-in replacement. Our code is publicly available on github.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Turbo-Muon: making a popular AI optimizer faster and just as good

Overview: what this paper is about

This paper tries to make a powerful AI training method, called an “orthogonality-based optimizer,” faster. The best-known example is the Muon optimizer. Muon often trains models better than the standard AdamW optimizer, but it has one slow part: it repeatedly “orthogonalizes” (makes at right angles) big matrices, which takes lots of time on GPUs. The authors propose a simple trick called “preconditioning” that helps a common orthogonalization method converge faster. They call their improved version Turbo-Muon. It runs quicker, needs fewer steps, and keeps the same model quality.

Objectives: what questions the paper asks

To make the slow step faster, the paper focuses on three goals:

- Can we start the orthogonalization process from a better place so it needs fewer steps?

- Can we reduce the extra computation without hurting accuracy?

- Will this speedup actually make end-to-end training faster on real tasks, with no extra tuning?

Methods: how they did it, in everyday language

Orthogonality means “at right angles.” In machine learning, making weight updates more orthogonal can help training be more stable and efficient. Muon does this by repeatedly “polishing” a matrix so it gets closer to perfectly orthogonal. A popular polishing method is called Newton–Schulz (NS). Think of NS like ironing a wrinkled shirt multiple times: each pass makes it smoother, but every pass costs time.

The authors’ idea: precondition the matrix before ironing. Their preconditioner is called AOL (Almost Orthogonal Layer):

- AOL looks at how the columns of the matrix interact (via a “Gram matrix”) and rescales each column so the matrix starts out closer to orthogonal.

- Because the starting point is better, NS needs fewer “iron passes” to reach the same smoothness.

Two practical tricks make this efficient:

- Reuse calculations: computing the Gram matrix for AOL is the same kind of calculation NS uses first anyway, so they cache it and avoid doing extra work.

- Smarter GPU code: they add a fused GPU kernel and use symmetry so the computer does less duplicate work.

In simple terms: AOL sets up the matrix so NS has less to do, and the code makes sure that extra setup barely costs anything.

Findings: what they discovered and why it matters

Here’s what they found:

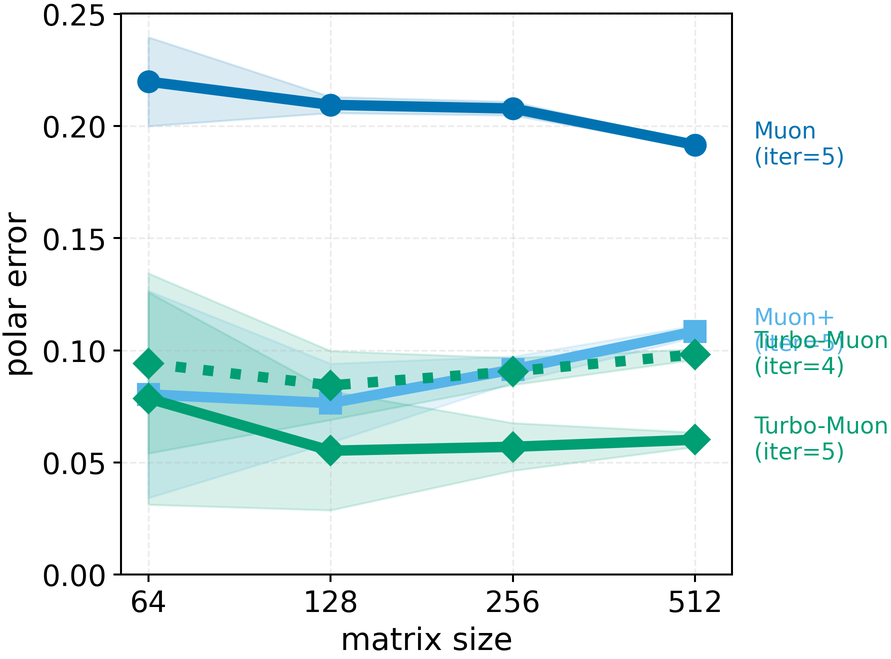

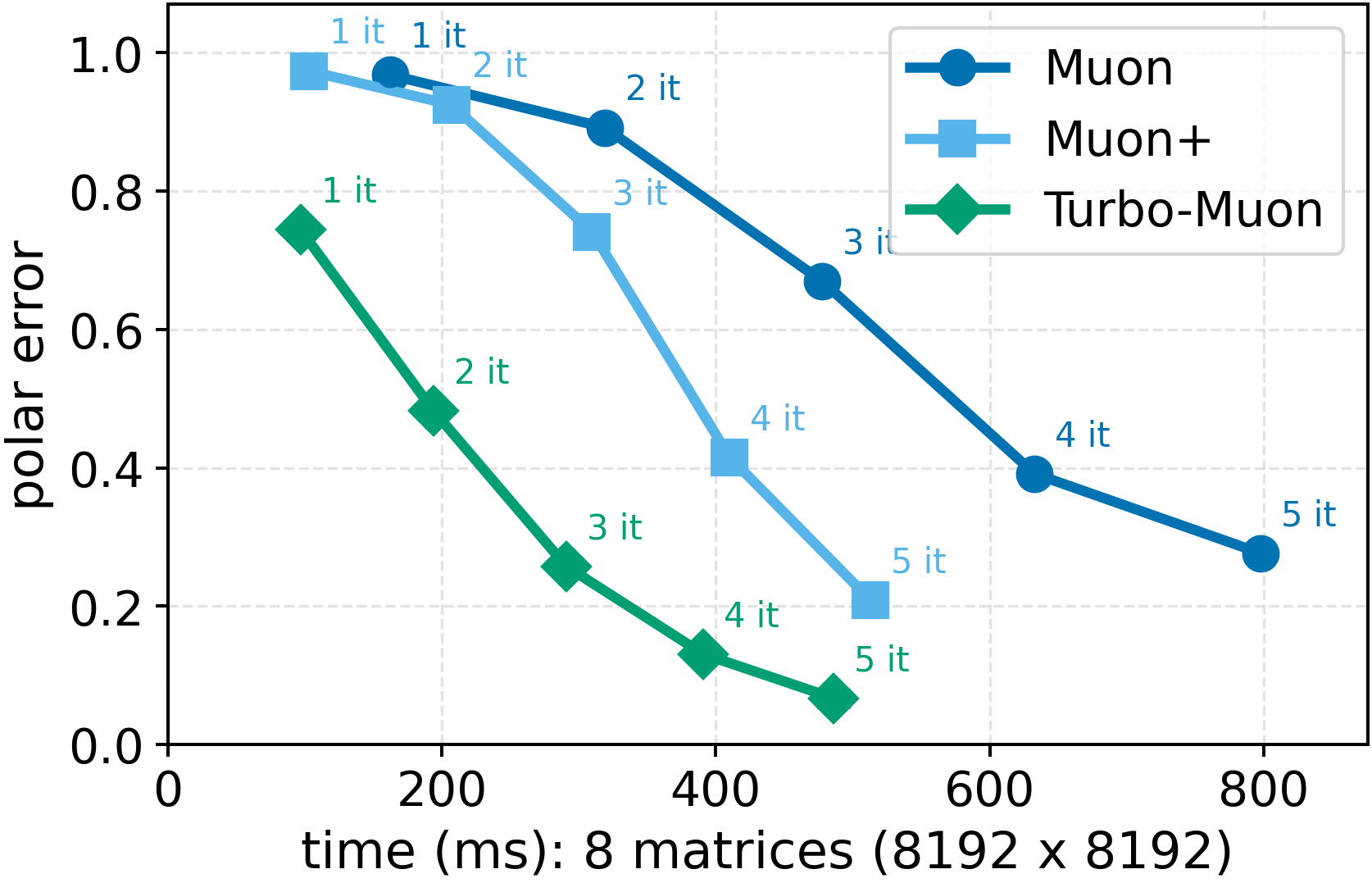

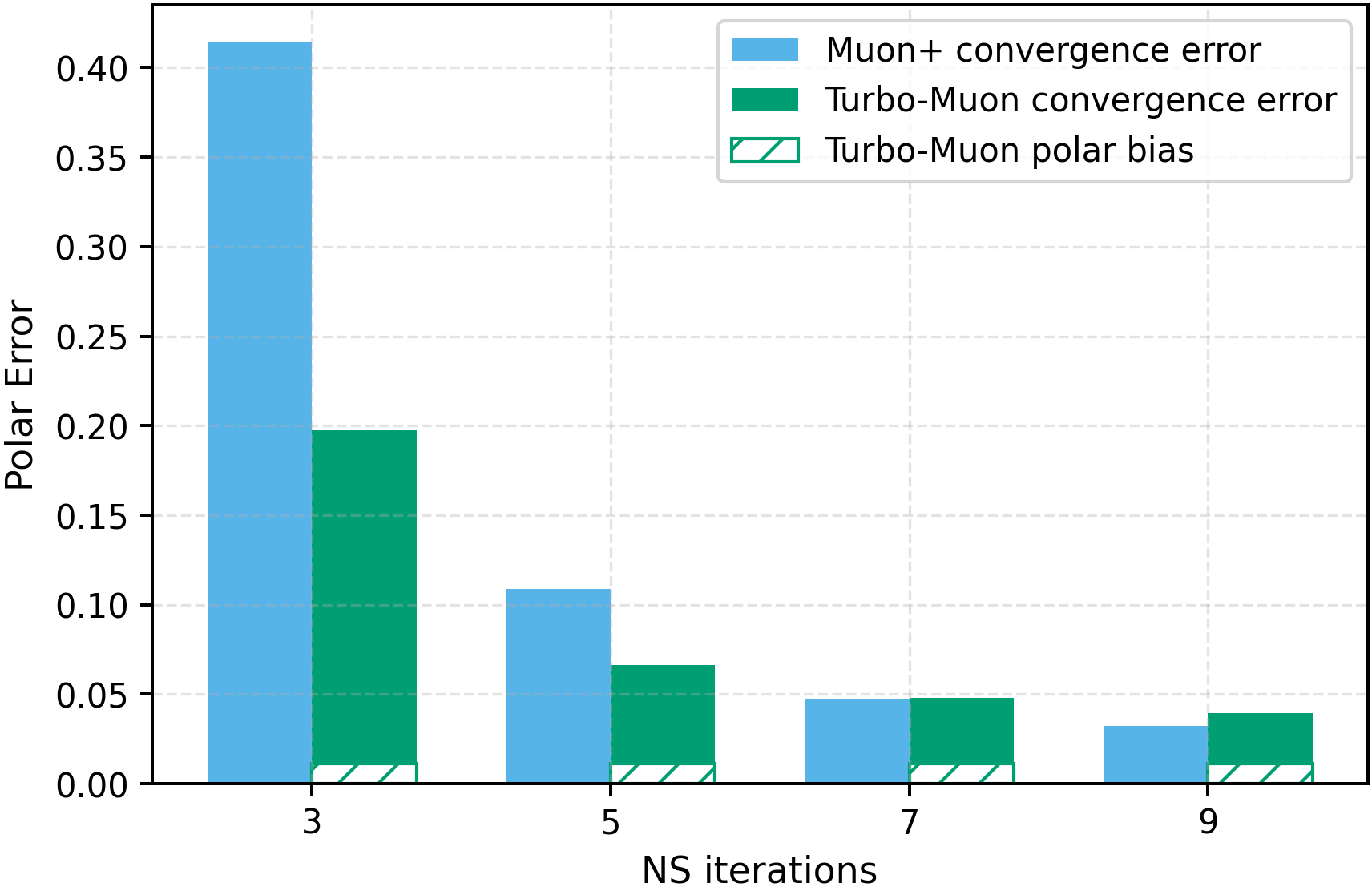

- Faster orthogonalization: Their preconditioning helps the NS method converge faster. In fact, they can remove one of the usual five NS iterations while matching or improving the final accuracy of the orthogonalization. Their implementation speeds up the NS step by up to about 2.8×.

- End-to-end training speedups: In real training runs (LLMs like NanoGPT and a vision task like CIFAR-10), Turbo-Muon cuts total training time by about 5–10%. That’s meaningful when training big models.

- No tuning needed: You can drop in Turbo-Muon in place of Muon without changing hyperparameters, and it keeps or improves model performance.

- Stable and safe: Even though AOL slightly changes the target of the orthogonalization, the paper shows this still gives a valid “steepest descent” direction. In practice, training remains stable, and final accuracy is unaffected—even when using many NS iterations.

Why this matters: Orthogonality-based optimizers are promising but can be costly. Making the slow part faster without losing quality helps more people use them for bigger, more efficient models.

Implications: why this could be useful

Turbo-Muon makes an already strong optimizer more practical:

- It reduces the time spent in the optimizer step, especially helpful for medium-to-large models where every minute counts.

- It keeps training stable and performance high, so teams don’t have to retune everything.

- It can be adopted quickly: it’s a simple drop-in replacement and is publicly available.

Overall, this work helps push AI training toward being faster, more efficient, and easier to scale—useful for both research and industry, and good for saving compute time and energy.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper’s theory, algorithms, systems implementation, and empirical evaluation.

Theory and analysis

- Lack of analytical bounds on AOL-induced bias: No formal upper bounds for the bias term ε_bias(AOL, X) in terms of matrix spectrum, coherence, condition number, aspect ratio, or near-orthogonality measures; only empirical observations are provided.

- Missing convergence-rate guarantees with preconditioning: While AOL improves empirical convergence of Newton–Schulz (NS), there is no theorem quantifying iteration savings or asymptotic rate under assumptions on the singular value distribution.

- No characterization for rectangular matrices: Claims “results generalize,” but there is no formal treatment of AOL’s effect on NS convergence and bias for tall/skinny or wide/fat matrices (pseudo-orthogonality settings).

- Unclear behavior under rank deficiency or extreme ill-conditioning: AOL assumes full rank and near column-orthogonality; theoretical guarantees and failure modes for nearly singular or highly ill-conditioned updates are not established.

- Optimality of AOL vs. alternative diagonal scalings: No comparison or theory for other diagonal/balancing preconditioners (e.g., Sinkhorn-Knopp, row/column norm equalization, spectral norm estimates) that might further reduce iterations or bias.

- Static vs. iterative preconditioning: Only a single-shot preconditioner at the first step is analyzed; no theory for re-preconditioning between NS iterations or for adaptive preconditioning based on online error estimates.

- Interaction with polynomial parameterization: The paper reuses NS polynomial coefficients designed for 5 iterations when running 4; there is no analysis on how to optimally re-tune coefficients for AOL-preconditioned dynamics or different iteration counts.

- Induced-norm interpretation not quantified: While Turbo-Muon is framed as steepest descent in a modified induced norm, the implications for optimization dynamics (e.g., convergence rates, implicit regularization) are not derived or bounded.

Algorithmic design and robustness

- Early-stopping or adaptive-iteration selection is missing: No mechanism to adapt the number of NS iterations based on a cheap a priori/a posteriori polar-error estimate; “remove one iteration” is a fixed heuristic.

- Numerical stability under low precision not fully explored: AOL needs reductions and inverse square roots; robustness in FP16, BF16, or FP8 (accumulation precision, epsilon handling, overflow/underflow) is not characterized.

- Sensitivity to scaling vector

s: No safeguards, clipping, or epsilon strategies are specified for very small or large entries ins; stability and performance under extreme variance across columns remain untested. - Limited exploration of heavy-tailed and non-Gaussian cases: Beyond a Levy example in the appendix, there is no systematic paper across tail indices, anisotropy, or structured gradient statistics seen in large-scale training.

- Non-conv layer shapes and grouped/depthwise convs: AOL and the fused kernels’ behavior for grouped/depthwise convolutions or highly rectangular reshaped kernels is not validated.

- Interactions with training techniques: Effects with gradient clipping, weight decay, norm scaling, EMA, FP8 heads, or gradient accumulation are not examined; potential conflicts or synergies are unknown.

Systems and implementation

- Memory overhead unquantified: Caching A0 = XᵀX to “make preconditioning free” increases memory footprint; its impact on peak memory, fragmentation, and OOM risk for large layers is not measured.

- Distributed/sharded training not evaluated: Computing XᵀX under tensor/model parallelism can require costly communication; there is no analysis of communication overhead, overlap strategies, or scalability on multi-GPU/multi-node systems.

- Hardware portability and kernels: The added Triton kernel is evaluated on NVIDIA GPUs; performance and correctness portability to other accelerators (e.g., AMD, TPU) or different compiler stacks is not addressed.

- Kernel-level bottlenecks and autotuning: No investigation of occupancy, tiling, or fusion opportunities beyond a single added kernel; automated kernel parameter tuning and sensitivity across matrix sizes are unexplored.

- Cost model for amortization: The conditions (matrix sizes, batch sizes, hardware) under which AOL’s reuse of A0 yields net speedup are not formalized, making it hard to predict benefits for new workloads.

Empirical evaluation and scope

- Limited task diversity and scale: Results are shown for NanoGPT (124–144M) and CIFAR-10 speedruns; no evaluation on larger LLMs with distributed training, longer contexts, or modern vision backbones at scale.

- No end-to-end Pareto against alternative optimizers: Comparisons focus on Muon variants; comprehensive wall-clock vs. final quality trade-offs against AdamW, Sophia, Adafactor, and other orthogonality-based optimizers are absent.

- Incomplete comparison to Dion in realistic settings: The 1.3B “step time” comparison flags Dion convergence issues but lacks full training curves, final quality, and total-time-to-target comparisons at realistic distributed scales.

- Hyperparameter invariance claim under-tested: “No hyperparameter tuning” is asserted but not stress-tested across diverse LRs, schedulers, batch sizes, and regularization settings; robustness boundaries are unknown.

- Rectangular layer prevalence: Many transformer layers (e.g., embeddings, projections) are highly rectangular; empirical results predominantly show square or reshaped conv cases without a stratified analysis by aspect ratio.

- Lack of ablations: No ablation on AOL components (absolute vs. signed Gram entries, 1-norm vs. 2-norm row sums, epsilon/clipping), nor on the contribution of caching vs. the fused kernel vs. iteration reduction.

- Target-error calibration: Polar error is the main metric, but its correlation with downstream optimization quality is not rigorously established; orthogonality error and its impact on training dynamics remain under-explored.

- Generalization and stability over long runs: The paper reports short-to-medium runs; there is no evidence on long training horizons (instabilities, regressions), especially for large models and curriculum changes.

Extensions and integrations

- Combining with alternative orthogonalizers: It is unclear whether AOL preconditioning similarly accelerates other schemes (Cayley, exponential map, Cholesky-based, QR), or hybrid pipelines mixing methods.

- Interaction with low-rank or block-wise approximations: Can AOL enable fewer iterations when coupled with low-rank updates (as in Dion) or block-diagonal/blocked orthogonalization to further cut costs?

- Adaptive or layer-wise policies: No exploration of per-layer iteration counts or preconditioner strength as a function of layer size, aspect ratio, or measured error, which could yield larger global speedups.

- On-the-fly coefficient learning: The potential to learn or schedule NS polynomial coefficients jointly with AOL preconditioning (e.g., via meta-optimization) to further reduce iterations is not investigated.

- Practical error estimation: There is no cheap, deployable estimator for polar error to drive adaptive decisions (iteration count, re-preconditioning, fallback), which limits safe deployment at scale.

These gaps point to concrete next steps: derive bias and convergence bounds for AOL-preconditioned NS (including rectangular and ill-conditioned cases), quantify memory/communication costs in distributed settings, broaden empirical validation to large-scale LLMs with end-to-end Pareto frontiers, and develop adaptive policies (iteration selection, coefficient tuning, and preconditioning strength) guided by fast error estimators.

Glossary

- AdamW: An adaptive gradient optimizer that decouples weight decay from the gradient update to improve generalization. "which has been shown to consistently surpass AdamW~\cite{kingma2014adam,loshchilovdecoupled} across diverse training regimes~\cite{wen_fantastic_2025}"

- Adaptive polynomial factors: Iteration-varying coefficients used in the Newton–Schulz polynomial update to accelerate convergence. "integrating Triton kernels~\cite{tillet2019triton} and adaptive polynomial factors from~\cite{cesista2025muonoptcoeffs}, computed for five iterations."

- Almost Orthogonal Layer (AOL): A column-wise scaling based on the Gram matrix that moves a matrix closer to orthogonality while improving conditioning. "the ``Almost Orthogonal Layer" (AOL) parametrization introduced by \cite{prach2022almost}"

- AOL preconditioning: Using AOL as a preprocessing step to improve the starting point and convergence of iterative orthogonalization. "We introduce a preconditioned NewtonâSchulz formulation based on almost-orthogonal (AOL) preconditioning~\cite{prach2022almost}."

- Björck–Bowie algorithm: An iterative method equivalent to Newton–Schulz for projecting matrices toward orthogonality. "(also known as Bj\"orck--Bowie algorithm)"

- Cayley transform: A mapping from skew-symmetric to orthogonal matrices via (I−A)(I+A){-1}, commonly used to parameterize orthogonal matrices. "The Cayley transform~\citep{Cayley_1846} establishes a bijection between skew-symmetric and orthogonal matrices through "

- Cholesky-based method: Orthogonalization via triangular decomposition of MMT (Cholesky factorization) followed by solving with the inverse factor. "the Cholesky-based method~\citep{hu_recipe_2023} orthogonalizes a matrix with a triangular decomposition "

- Condition number: The ratio of largest to smallest singular values (σ_max/σ_min), indicating numerical sensitivity and conditioning. "does not modify the condition number, since the ratio remains unchanged."

- Concentration phenomena: High-dimensional probability effects whereby random vectors or matrices exhibit near-orthogonality and other regularities. "as a byproduct of concentration phenomena which tend to enforce near orthogonality"

- Exponential map: A way to generate orthogonal matrices by exponentiating a skew-symmetric matrix. "The Exponential map~\citep{singla_skew_2021} also leverages skew-symmetric matrices, generating while typically approximating the exponential via truncated series."

- Fast inverse square root: A hardware-friendly approximation for computing 1/√x efficiently. "with the fast inverse square root computed element-wise{~\cite{todo_fast_inverse_sqrt})"

- Frobenius norm: The square root of the sum of squared entries of a matrix, used as a global scaling measure. "normalizing the input matrix by its Frobenius norm."

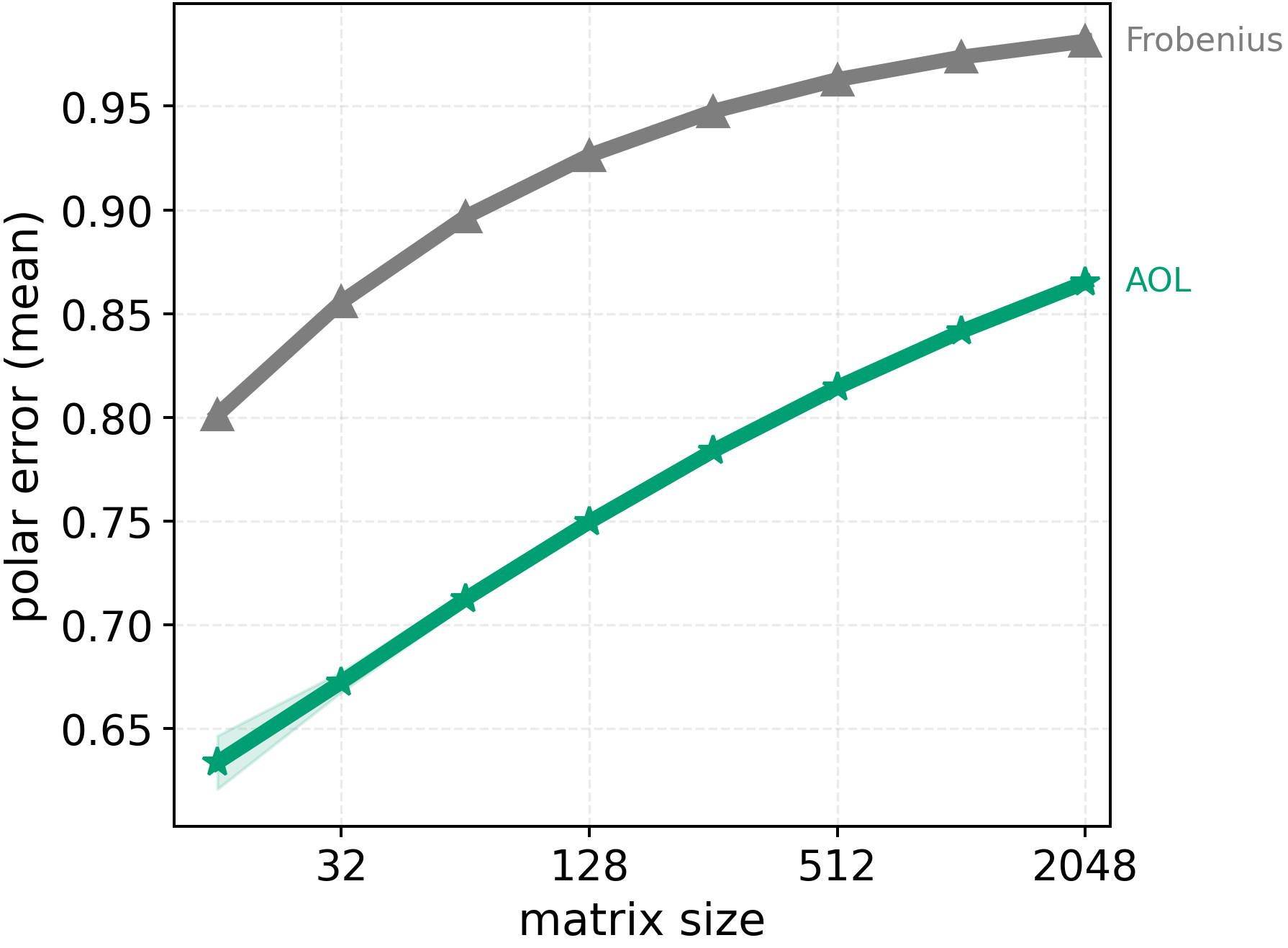

- Frobenius normalization: Rescaling a matrix by the inverse of its Frobenius norm to ensure convergence conditions for iterative methods. "AOL consistently outperforms the usual Frobenius normalization."

- Gram matrix: The matrix XT X capturing inner products between columns (or rows) of X. "the row sum of the Gram matrix acts as a scaling vector applied column-wise to ."

- Heavy-tailed gradients: Gradient distributions with heavier tails than Gaussian, often observed in deep learning and linked to optimization stability. "stabilize training under heavy-tailed gradients"

- Induced operator norm: The norm of a linear operator defined as the maximum output norm over unit input norm, e.g., ℓ2→ℓ2 spectral norm. "steepest descent direction in a induced operator norm."

- Isotropic update directions: Update directions with equal variance in all directions, improving stability and convergence. "yielding isotropic update directions and smoother convergence dynamics."

- Levy distribution: A heavy-tailed probability distribution used to stress-test algorithms under non-Gaussian statistics. "matrices sampled from a Levy distribution"

- Low-rank updates: Parameter updates constrained to a low-rank subspace to reduce compute/communication cost in large-scale training. "Dion's low-rank updates--which shine at larger scales--still degrade convergence."

- Model sharding: Partitioning a model’s parameters across devices for memory and compute scalability. "model sharding (i.e. splitting a large neural network model into smaller parts)"

- Modified Gram-Schmidt QR factorization: A numerically stable QR factorization variant that orthogonalizes vectors iteratively. "The Modified Gram-Schmidt QR factorization~\citep{LaPlace1820} finds the polar factor with an iterative process (one iteration per row)."

- Newton–Schulz algorithm: An iterative polynomial method to approximate the polar factor and orthogonalize matrices efficiently. "the iterative Newton-Schulz algorithm ~\citep{bjorck1971iterative,anil_sorting_2019}"

- Normalized polar error: The Frobenius-distance error to the true polar factor, normalized by matrix size. "To assess approximation quality, we define the normalized polar error as:"

- Orthogonal manifold: The set of orthogonal matrices forming a smooth geometric manifold. "updates are projected toward the orthogonal manifold"

- Orthogonality-based optimizers: Optimizers that enforce or approximate orthogonal updates to stabilize and accelerate training. "Orthogonality-based optimizers, such as Muon, have recently shown strong performance"

- Orthogonality error: A metric quantifying deviation from orthogonality (e.g., ||XT X − I||_F). "we define the orthogonality error as"

- Polar error: The distance between an approximate orthogonalization and the true polar factor, often measured in Frobenius norm. "target polar error (i.e., the Frobenius distance to the closest orthogonal matrix)"

- Polar factor: The closest orthogonal matrix to a given matrix in the Frobenius norm sense, equal to U VT from SVD. "This matrix is the polar factor, given by"

- Preconditioning: A transformation applied before an algorithm to improve its convergence properties. "We introduce a preconditioning procedure that accelerates Newton-Schulz convergence"

- Pseudo-orthogonal: A rectangular matrix that satisfies only one of XT X = I or X XT = I. "the matrix is referred to as pseudo-orthogonal."

- Quintic polynomial expansions: Fifth-order polynomial updates used in NS iterations to accelerate convergence toward the polar factor. "relies on quintic polynomial expansions to approximate the polar factor efficiently"

- Sharpness: A measure of loss landscape curvature affecting step size and descent direction in steepest-descent formulations. "with the gradient and sharpness."

- Singular value decomposition (SVD): Factorization X = U Σ VT into orthogonal matrices and nonnegative singular values. "The singular value decomposition (SVD) of is given by"

- Skew-symmetric matrix: A matrix A with AT = −A, used to parameterize orthogonal matrices via Cayley or exponential maps. "bijection between skew-symmetric and orthogonal matrices"

- Spectral norm: The largest singular value of a matrix, equal to its ℓ2→ℓ2 operator norm. "This also defines the spectral norm of a matrix : ."

- Spectral normalization: Scaling technique ensuring spectral norm constraints to guarantee convergence of certain iterations. "achieving fast convergence under spectral normalization."

- Steepest descent: The direction minimizing a linearized loss plus a norm-regularized step size; yields polar factor updates under spectral norm. "the steepest descent update in spectral norm is (informally) defined as:"

- Stiefel manifold: The set of matrices with orthonormal columns (or rows), a target of orthogonalization procedures. "projects matrices toward the Stiefel manifold"

- Tail index: A parameter quantifying the heaviness of distribution tails; lower values indicate heavier tails. "the tail index ranges from $1.0$ to $1.8$"

- Tensor-parallel decomposition: A distributed strategy that splits tensor operations across devices to scale model training. "and tensor-parallel decomposition."

- Triton kernels: Custom GPU kernels written in the Triton language to optimize matrix operations beyond stock libraries. "integrating Triton kernels~\cite{tillet2019triton}"

- Wall-clock overhead: Extra real-time cost added to training, measured independently of theoretical FLOPs. "In these methods, wall-clock overhead scales with the number of iterative steps"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be adopted now as drop-in improvements to existing machine learning workflows, requiring minimal code changes and no hyperparameter tuning.

- Faster training of LLMs and vision systems

- Sector: software, AI, cloud computing

- Use case: Replace the Newton–Schulz orthogonalization step in Muon with Turbo-Muon (AOL preconditioning + fused Triton kernels) to reduce optimizer overhead and end-to-end training time by 5–10% in medium-scale setups (e.g., 1.3B parameter models, single A100/H100 GPUs, batch sizes limited by memory).

- Tools/workflows: Integrate the authors’ “flash-newton-schulz” implementation as a drop-in optimizer backend; set NS iterations to 4; monitor polar error; fallback to 5 iterations where needed.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU availability with Triton support; matrices of moderate-to-large dimension; heavy-tailed gradient regimes are supported but extreme distributions may require runtime monitoring.

- Cost and energy savings in ML operations

- Sector: energy, enterprise IT, MLOps

- Use case: Reduce compute budget and carbon footprint for training runs by shortening wall-clock time; aggregate savings across repeated experiment cycles, nightly retraining, or model refreshes in production.

- Tools/workflows: Add a “Turbo-Muon mode” to training pipelines; track kWh and CO₂ per run; automate iteration-count selection (default 4) with a polar-error guardrail.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Savings are most pronounced when optimizer overhead is 10–20% of step time (common in medium-scale and batch-limited settings).

- Improved throughput in edge and federated fine-tuning

- Sector: mobile/edge computing, robotics, IoT

- Use case: On-device or client-side fine-tuning with limited compute/thermal budgets benefits from reduced per-step optimizer overhead; enables more frequent updates or shorter adaptation windows.

- Tools/workflows: Integrate Turbo-Muon in lightweight client training loops; use cached Gram matrix and elementwise scaling to minimize memory bandwidth.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Works best on GPUs or accelerators supporting Triton-like kernels; on CPU-only or tiny accelerators, benefits depend on matmul throughput.

- Reliability-focused training with orthogonality-based optimization

- Sector: healthcare, finance, safety-critical systems

- Use case: Maintain or improve convergence stability while speeding up training; validated on language and vision tasks with comparable or better final loss versus Muon/Muon+.

- Tools/workflows: Adopt Turbo-Muon in compliance-sensitive pipelines where optimizer changes must be low-risk; apply A/B validation using the paper’s metrics (polar error, validation loss).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Gains rely on the AOL preconditioner reducing initial polar error; benefits are robust without retuning hyperparameters.

- Academic experimentation at lower cost and faster iteration cycles

- Sector: academia, education

- Use case: Shorten experiment loops by 5–10% in end-to-end training; run more ablations or larger sweeps with the same budget; teach modern polar factor approximations and preconditioning in optimization courses.

- Tools/workflows: Use the public GitHub code to replicate CIFAR-10 speedrun and NanoGPT benchmarks; instrument polar error, approximation error, and bias components as teaching material.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Students and researchers operate on modern GPUs; Triton present; capacity to instrument training scripts.

- Library and framework integration

- Sector: software tooling

- Use case: Incorporate Turbo-Muon in optimizer libraries (e.g., PyTorch optimizers, Hugging Face Transformers), distributed training stacks (e.g., DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM, Colossal-AI), or kernel libraries (Triton).

- Tools/products: A PyPI package or framework plugin shipping fused kernels, AOL preconditioning, and iteration control; an “orthogonalization backend” setting (Muon vs Turbo-Muon).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Kernel maintenance aligned with framework releases; test coverage across dtypes (BF16/FP16/FP32); careful handling in sharded regimes where matmul communication can dominate.

Long-Term Applications

The following opportunities require additional research, systems integration, or scaling efforts to realize their full impact.

- Carbon-aware and energy-efficient AI standards in industry and policy

- Sector: policy, sustainability, cloud procurement

- Use case: Codify adoption of efficient orthogonalization backends (like Turbo-Muon) into green AI metrics, procurement guidelines, and sustainability reporting.

- Tools/workflows: Standard benchmarks reporting optimizer overhead, polar error, and kWh per training objective; best-practice playbooks for medium-scale batch-limited regimes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Broad acceptance of orthogonality-based optimizers; agreement on reporting standards; verification infrastructures.

- Hardware-level acceleration of orthogonalization and preconditioning

- Sector: semiconductors, HPC

- Use case: Add ASIC/firmware support for Gram-matrix caching, symmetric matmul exploitation, and fused rescaling kernels; expose hardware primitives for AOL-like preconditioning.

- Tools/products: Vendor libraries (cuBLAS/rocBLAS) with explicit support for NS-quintic steps, symmetric matmul, and elementwise scaling fused into kernels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor commitment and ecosystem support; careful numerics at low precision (BF16/FP8).

- Adaptive optimizers that switch policies across scales and regimes

- Sector: AI systems, distributed training

- Use case: Combine Turbo-Muon with adaptive polynomial coefficients, low-rank updates (Dion), and auto-tuning to choose iteration counts and backends per layer, per device shard, or per training phase.

- Tools/workflows: Runtime controllers monitoring polar error and step-time; policies that disable NS iterations when benefits diminish; orchestration across tensor/pipe/data parallelism.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust telemetry; low-latency decisions; compatibility with communication-heavy sharded matmuls.

- Generalized preconditioning for iterative matrix algorithms beyond polar factor

- Sector: numerical linear algebra, scientific computing

- Use case: Extend AOL-style preconditioning to QR factorizations, spectral normalization, matrix inverse approximations, or exponential/cayley maps to speed up iterative schemes in ML and HPC.

- Tools/workflows: Algorithmic templates that cache shared matmuls; fused reductions; error decomposition (bias vs approximation) guiding iteration budgets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stability and accuracy analyses across tasks; proofs of convergence in broader settings.

- Privacy-preserving and robust training with efficient orthogonalization

- Sector: security, healthcare, finance

- Use case: Explore orthogonality-based optimizers in differentially private or adversarial training settings, where per-step compute is constrained; evaluate whether AOL preconditioning maintains privacy bounds and robustness.

- Tools/workflows: DP accounting integrated with Turbo-Muon; adversarial robustness benchmarks measuring impacts of preconditioning-induced bias on descent directions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Formal guarantees for induced norms under AOL; empirical validation in realistic privacy/robustness regimes.

- On-device continual learning and model personalization

- Sector: mobile, robotics, IoT

- Use case: Enable frequent incremental updates with reduced compute/heat, improving user personalization or adaptive control without cloud offloading.

- Tools/workflows: Lightweight training stacks embedding Turbo-Muon and monitoring polar error; adaptive iteration budgeting based on device thermals and battery.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accelerator support; careful memory management; domain validation on control and personalization tasks.

- Curriculum and standards for optimization education

- Sector: education

- Use case: Develop standardized teaching modules on polar decomposition approximations, preconditioning, induced norms, and Triton kernel design; provide reference implementations.

- Tools/workflows: Courseware with interactive labs, instrumented training scripts, and visualizations of polar/approx/bias error curves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Educator adoption; alignment with evolving frameworks and numerical best practices.

- Sector-specific accelerated model refresh cycles

- Sector: healthcare (clinical NLP, imaging), finance (risk modeling), energy (grid forecasting)

- Use case: Shorten time-to-deployment for high-stakes models that require frequent retraining, while preserving or improving convergence stability.

- Tools/workflows: Operational playbooks to switch optimizer backends; SLA-aware training schedules; model governance that tracks optimizer changes and performance deltas.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain-specific validation; regulator and stakeholder acceptance; integration with existing MLOps governance frameworks.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.