Guided Self-Evolving LLMs with Minimal Human Supervision (2512.02472v1)

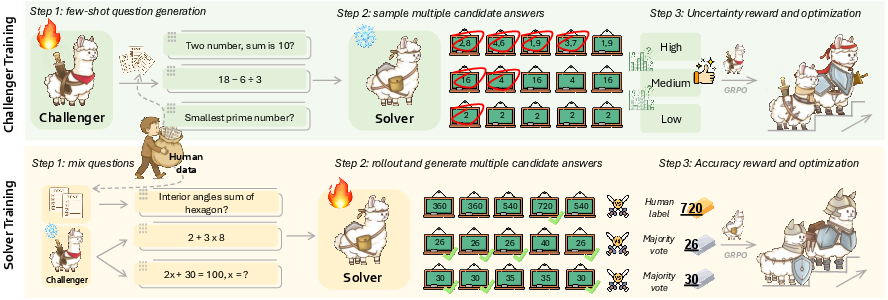

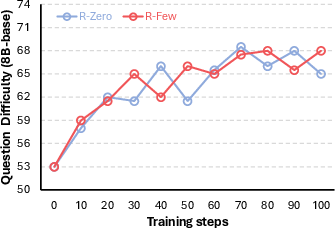

Abstract: AI self-evolution has long been envisioned as a path toward superintelligence, where models autonomously acquire, refine, and internalize knowledge from their own learning experiences. Yet in practice, unguided self-evolving systems often plateau quickly or even degrade as training progresses. These failures arise from issues such as concept drift, diversity collapse, and mis-evolution, as models reinforce their own biases and converge toward low-entropy behaviors. To enable models to self-evolve in a stable and controllable manner while minimizing reliance on human supervision, we introduce R-Few, a guided Self-Play Challenger-Solver framework that incorporates lightweight human oversight through in-context grounding and mixed training. At each iteration, the Challenger samples a small set of human-labeled examples to guide synthetic question generation, while the Solver jointly trains on human and synthetic examples under an online, difficulty-based curriculum. Across math and general reasoning benchmarks, R-Few achieves consistent and iterative improvements. For example, Qwen3-8B-Base improves by +3.0 points over R-Zero on math tasks and achieves performance on par with General-Reasoner, despite the latter being trained on 20 times more human data. Ablation studies confirm the complementary contributions of grounded challenger training and curriculum-based solver training, and further analysis shows that R-Few mitigates drift, yielding more stable and controllable co-evolutionary dynamics.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Plain‑English Summary of “Guided Self‑Evolving LLMs with Minimal Human Supervision”

What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching an AI to get better at reasoning mostly on its own. The authors build a training method called R‑Few that lets a LLM (an AI that reads and writes text) practice by generating its own questions and answers, while still getting a tiny bit of guidance from humans. The goal is to help the AI keep improving without drifting off‑track or getting stuck.

What questions were the researchers trying to answer?

They focused on three simple questions:

- How can an AI keep improving by practicing with itself without needing tons of human‑written data?

- How can we stop it from “drifting,” like learning bad habits or getting stuck asking the same kinds of easy questions?

- Can a very small amount of human guidance (just 1–5% of a dataset) make self‑practice stable, steady, and strong?

How did they do it?

Think of two students working together:

- One student, the Challenger, writes practice questions.

- The other student, the Solver, tries to answer them.

Here’s the twist: sometimes the Challenger gets to peek at a few real, high‑quality, human‑made examples (0 to 5 short examples) before writing new questions. These are like “anchors” that keep the questions realistic and on‑topic. Other times, the Challenger writes freely to explore new ideas. This mix keeps creativity while staying grounded.

To make learning efficient, the Solver uses a “just‑right” homework plan (a curriculum). After the Solver tries a bunch of questions, the system estimates how hard each one is. Then it selects the middle‑difficulty ones for training—the ones that are not too easy and not too hard. This “Goldilocks zone” helps the Solver learn fastest.

Key ideas, translated:

- Self‑play: practicing against yourself (the AI writes questions and answers them).

- Few‑shot grounding: giving the Challenger a few human examples in its prompt so it stays on track.

- Concept drift: when practice slowly leads the AI to misunderstand things or learn bad habits.

- Diversity collapse: when the AI keeps making the same kind of problem over and over.

- Curriculum learning: training on problems that are “just right” in difficulty, not too easy or too hard.

How the loop runs, in everyday terms:

- The Challenger writes several candidate questions.

- The Solver attempts them multiple times. A simple checker (like answer agreement or a programmatic judge) estimates how often the Solver succeeds.

- The system keeps questions of medium difficulty to train on next time.

- The Challenger also gets a gentle nudge to write questions that are neither duplicates nor trivially easy/hard, and that stay near the style of the human “anchor” examples.

- Repeat this cycle many times so both the Challenger and Solver improve together.

What did they find?

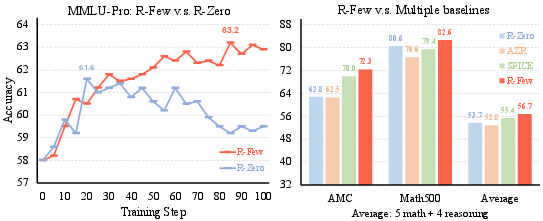

The authors tested R‑Few on math and general reasoning benchmarks and compared it with other self‑play methods.

Main takeaways:

- Stronger gains with very little human data: Using only 1–5% of a large human dataset as anchors, R‑Few improved steadily across tasks. For example, with the Qwen3‑8B model, R‑Few improved math scores by about +3 points over a popular self‑play baseline (R‑Zero), and reached performance similar to a system trained on about 20× more human data.

- Scales with model size: The bigger model (8B) benefited even more than the smaller one (4B). With 5% anchors, it even matched or beat a heavily supervised competitor on average.

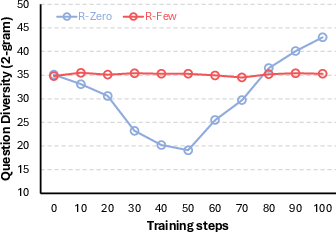

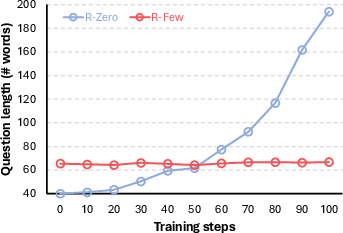

- More stable learning: Compared to an unguided method, R‑Few avoided two common problems:

- It didn’t make questions unnecessarily long just to “look” harder (a kind of reward hacking).

- It kept question variety healthy instead of collapsing into repetitive patterns.

- Each piece matters: Removing any one of the parts—(1) Challenger training, (2) a small warm‑up to help the Challenger follow formats, or (3) the “just‑right” curriculum—hurt results. That means these parts work together.

- Domain steering works: Picking human anchor examples from a specific subject (like math) boosts that subject the most, and some skills transfer (math anchors also help physics). This shows you can steer what the model learns by choosing anchor domains.

Why does this matter, and what’s next?

This work shows you can get stable, ongoing AI improvement without huge amounts of human labels. A tiny set of high‑quality human examples can guide a mostly self‑driven training loop to avoid drifting, keep variety, and learn faster. That’s cheaper, more scalable, and more controllable.

Possible impacts and future directions:

- Lower cost training: Strong reasoning with much less human effort.

- Targeted growth: Choose anchor domains (e.g., law, medicine, math) to steer the model’s strengths.

- Better safety and reliability: Grounding reduces weird or off‑topic behavior as the model evolves.

- Next steps: Add stronger automatic checks (verifiers), make training more efficient, and extend to open‑ended tasks where there isn’t a single correct answer.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of concrete gaps and unanswered questions that future work could address:

- Formalization and implementation clarity

- The Challenger reward (Eq. 4) describes an Align term in the text (“measures the semantic or structural proximity… via cosine similarity”), but the displayed reward equation omits it; the exact formulation, weight, and effect of this alignment regularizer are unclear and untested.

- Several equations contain typos or missing brackets/terms (e.g., chal/sol rewards, success-rate notation), making the precise optimization objective ambiguous; a complete, disambiguated specification is needed for faithful reproduction.

- Criteria for “valid” questions and the exact RepPenalty definition (duplicate detection, similarity thresholds, embedding choices) are not fully specified, limiting reproducibility and adversarial analysis.

- Anchor data usage and selection strategy

- Only two anchor proportions (1% and 5%) are evaluated; the sensitivity curve across anchor sizes, data quality, and label noise is unknown.

- The k-shot range is fixed to k∈[0,5] with random sampling; no paper of adaptive k schedules (e.g., decreasing k over time), anchor retrieval strategies, or active selection to maximize coverage/diversity.

- Domain composition of anchors is only qualitatively explored; optimal cross-domain mixtures, balancing strategies, and the effect of domain skew/imbalance remain open.

- Curriculum design and uncertainty estimation

- The mid-quantile curriculum is fixed at [0.3, 0.7]; no ablations on different quantiles, adaptive schedules, or per-domain/per-skill calibration are reported.

- The success-rate estimator depends on M rollouts, but M, decoding settings, and calibration quality are unspecified; the reliability, variance, and computational overhead of uncertainty estimates are not analyzed.

- Potential forgetting of very easy/hard samples under mid-quantile filtering is unaddressed; buffer/replay strategies or periodic edge-case rehearsal are not explored.

- Baseline and ablation coverage

- There is no baseline that uses the same 1–5% human anchors with simple SFT (or SFT+small RL) to isolate the added value of guided self-play over human-only fine-tuning.

- No ablations on anchor alignment strength, RepPenalty weight, λhum (set to 2.0), number of shots k, or alternative similarity metrics (e.g., structural vs. semantic) for grounding.

- The warm-up SFT phase is mentioned but not described (data size, source, prompts); its supervision footprint and independent contribution are unclear.

- Compute, efficiency, and scaling behavior

- Training budgets (GPU hours, batch/group sizes, rollout counts, wall-clock time) and per-iteration costs are not reported; cost-performance tradeoffs vs. baselines remain unknown.

- No scaling-law analysis with respect to model size, anchor size, or compute; long-horizon stability (beyond the shown steps) and eventual plateau/degeneration dynamics are not characterized.

- Verifiers, evaluation, and metrics

- Math evaluation uses GPT-4o as a judge and difficulty labeling uses Gemini 2.5; sensitivity to judge choice, potential bias, and reproducibility with open-source verifiers are not assessed.

- For general reasoning, only greedy EM is reported; richer measures (calibrated accuracy, rationale quality, reasoning depth) and multi-judge consensus are not explored.

- Diversity is measured via 2-gram lexical diversity and length; semantic/reasoning-pattern diversity, novelty relative to anchors, and task-structure variety are not measured.

- Possible benchmark contamination from WebInstruct overlap is not ruled out; no decontamination or leakage analysis is provided.

- Robustness and safety

- The framework’s behavior under noisy, adversarial, or mis-specified anchors (wrong labels, off-domain seeds) is untested; robust grounding and outlier detection strategies remain open.

- Safety filtering for self-generated questions/answers is unspecified; mechanisms to prevent harmful or policy-violating content during self-play are not described.

- Reward hacking beyond verbosity (e.g., exploiting invalidity detectors, subtle duplication, or formatting heuristics) is not systematically probed; formal threat models and defenses are absent.

- Bias and fairness considerations tied to anchor selection and self-amplification are not evaluated.

- Generality and transfer

- Experiments are limited to two base models (Qwen3-4B/8B) and one anchor source (WebInstruct); generalization to other model families, larger/smaller scales, and different anchor datasets is unknown.

- Extension to non-verifiable or open-ended tasks is stated as future work; concrete protocols for soft or preference-based verifiers, multi-criteria rewards, or tool-augmented verification are not provided.

- Transfer to multimodal or tool-augmented settings (retrieval, calculators, code interpreters) and the interaction between external tools and minimal human grounding remain unexplored.

- Theoretical understanding

- No theoretical guarantees are provided on stability, convergence, or avoidance of collapse under the proposed guided self-play with curriculum; conditions for when minimal anchors suffice to prevent drift are unknown.

- The bi-level optimization’s dynamics (e.g., fixed points, oscillations, mode collapse) under varying alignment strength and curriculum pressure are not analyzed.

- Diagnostics and monitoring

- There is no quantitative metric of “concept drift” relative to anchors or a held-out canonical distribution; methods for online drift detection, intervention points, and human-in-the-loop correction policies are not described.

- Error taxonomies and qualitative failure-case analyses (ambiguity, spurious reasoning, shortcutting) are limited; actionable diagnostics to steer Challenger/Solver updates are lacking.

- Reproducibility and fairness of comparisons

- Some baseline numbers are taken from prior reports under potentially different compute/data budgets; matched-resource comparisons and multiple random seeds are not provided.

- Code, training scripts, and exact prompts (including warm-up SFT prompts) are not reported; seed sensitivity and variance across runs are unknown.

Glossary

- 2-gram lexical diversity: A metric that counts unique consecutive two-word sequences to quantify textual diversity. "measured by 2-gram lexical diversity"

- Ablation paper: An experiment that removes or disables components to assess their individual impact on performance. "Ablation studies confirm the complementary contributions of grounded challenger training and curriculum-based solver training"

- Absolute Zero: A self-play training framework that operates with zero human data, relying on internal verification. "methods such as Absolute Zero and R-Zero often plateau quickly"

- Anchor data: A small, high-quality set of human-labeled examples used to guide synthetic generation. "only a small pool of high-quality ``anchor'' data"

- Bi-level optimization: A nested optimization setup where one model’s objective depends on another model’s optimized parameters. "The overall bi-level optimization can be expressed as"

- Challenger–Solver framework: A self-play setup with a generator (Challenger) proposing tasks and a solver answering them. "Self-Play ChallengerâSolver framework"

- Co-evolutionary dynamics: The joint, iterative improvement and interaction between the Challenger and Solver over training. "more stable and controllable co-evolutionary dynamics"

- Concept Drift: The tendency of a model’s learned behavior to shift away from correctness over time due to biased feedback loops. "(i) Concept Drift: Without external intervention or guidance, models tend to reinforce their own knowledge bias."

- Cosine similarity: A similarity measure between two vectors (e.g., embeddings) based on the cosine of the angle between them. "via cosine similarity in embedding space."

- Curriculum-based solver training: Training the solver on a curated subset of tasks chosen by difficulty to maximize learning efficiency. "curriculum-based solver training"

- Data-free training: Post-training that uses no human-labeled data, relying on self-generated tasks and signals. "Self-Play For Data-Free Training"

- Difficulty shaping: A reward design technique that pushes generation toward a desired difficulty level for stability. "using a linear difficulty shaping function to maintain stability"

- Difficulty sweet spot: A target difficulty range where tasks are challenging yet solvable, maximizing learning. "targeting a difficulty sweet spot"

- Diversity Collapse: The reduction of task or output diversity over training, causing exploration to stagnate. "(ii) Diversity Collapse: Since the underlying knowledge of the model is fixed, its self-generated challenges tend to converge toward familiar and low-entropy regions of the task space."

- Exact Match (EM): An evaluation metric that checks whether the predicted answer exactly matches the ground truth. "report Exact Match (EM) accuracy obtained via greedy decoding"

- Few-shot learning: Conditioning generation on a small number of in-context examples to guide outputs. "Generate G question candidates via few-shot learning:"

- Greedy decoding: A decoding strategy that selects the highest-probability token at each step without search. "obtained via greedy decoding"

- Grounded self-play: Self-play that uses external context or human data to constrain and validate generated tasks and answers. "a grounded self-play framework that retrieves contexts from a large document corpus"

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): A reinforcement learning algorithm variant used to update policies based on relative group rewards. "typically using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)"

- In-context grounding: Using human-provided examples within the prompt to steer generation toward desired semantics. "incorporates lightweight human oversight through in-context grounding and mixed training."

- Majority-vote pseudo-answer: A label obtained by aggregating multiple model responses and choosing the most frequent answer. "is the majority-vote pseudo-answer"

- Online curriculum: A dynamic process that ranks and filters tasks by current difficulty during training. "we introduce an online curriculum mechanism for the Solver."

- Quantile interval: A range of percentiles used to select tasks within a specific difficulty band. "select mid-range items according to the quantile interval [\tau_{\text{low}, \tau_{\text{high}]"

- RepPenalty: A penalty term that discourages generating duplicate or highly similar questions. "RepPenalty discourages duplicate questions."

- Reward hacking: Model behavior that exploits the reward signal (e.g., verbosity) without genuinely improving capability. "This suggests reward hacking, where the model exploits superficial features"

- Rollouts: Multiple sampled attempts by the model to solve a task, used to estimate success rates or uncertainty. "the Solver performs M rollouts and records the success rate"

- Self-consistency mechanism: A method that evaluates agreement among multiple generated solutions to estimate correctness. "A verifier or self-consistency mechanism then evaluates outputs"

- Self-evolving LLMs: LLMs that iteratively improve by generating and learning from their own tasks and experiences. "a self-evolving LLM framework that integrates limited human supervision"

- Self-play: Training where a model generates tasks and learns by competing against or evaluating itself. "self-play offers a promising paradigm"

- Success rate: The estimated probability that the solver correctly answers a given question based on sampled attempts. "records the success rate"

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT): Additional training on labeled data to improve adherence to instructions or formats. "we added a quick warm-up stage via supervised fine-tuning (SFT)"

- Uncertainty-driven curriculum: A selection strategy that prioritizes tasks with mid-level uncertainty to optimize learning. "Employs a purely uncertainty-driven curriculum with verifiable pseudo-labels:"

- Verifiable rewards (RLVR): Reinforcement learning signals derived from external verifiers or environments that can check correctness automatically. "RL with verifiable rewards (RLVR) uses externally defined verifiers"

- Verifier: A component that checks whether the solver’s output is correct, producing a scalar reward. "A verifier or self-consistency mechanism then evaluates outputs"

- Zone of proximal development: The difficulty range where tasks are neither too easy nor too hard, maximizing learning gains. "ensures that the Solver focuses on the zone of proximal development."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete ways the R-Few framework can be used today, based on its data-efficiency, grounded self-play design, and online curriculum mechanism.

- Data-efficient model upgrading for internal LLMs

- Sectors: software, cloud AI, enterprise IT

- Tools/workflows: implement Challenger–Solver self-play with GRPO; curate a 1–5% “anchor” dataset; run online curriculum selection (mid-uncertainty 30–70% zone); add quick SFT warm-up for prompt adherence

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to a competent base model; availability of a small, high-quality anchor set; verifiable or pseudo-verifiable tasks (e.g., math, code, structured QA); moderate compute for RL-style updates

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Domain-focused upskilling of assistants with targeted anchors

- Sectors: finance (analysis and reporting), legal (case reasoning), STEM education, enterprise knowledge assistants

- Tools/workflows: select domain-specific anchors (e.g., GAAP snippets, legal precedents, physics problems); few-shot sampling during generation; quantile-based difficulty gating

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable domain anchors; better gains in domains with objective correctness or well-defined rubrics; careful evaluation to prevent hallucination in open-ended domains

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Synthetic data augmentation for training and assessment

- Sectors: EdTech (practice problems), hiring/assessment platforms (reasoning tests), LLM training (self-generated Q&A)

- Tools/workflows: anchored Challenger to generate diverse, mid-difficulty items; solver-uncertainty ranking to filter; majority-vote or programmatic judges for labeling

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to a judge/verifier (e.g., programmatic judge, majority vote, or weak oracle); monitoring to avoid verbosity-based reward hacking

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Curriculum-based active learning and labeling triage

- Sectors: data labeling vendors, MLOps platforms, internal data ops

- Tools/workflows: compute per-item success rates; prioritize mid-uncertain items for human review; mix human-verified and synthetic items in training batches

- Assumptions/dependencies: calibrated uncertainty estimates; consistent judging/verification; integration with annotation tools

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Drift and collapse monitoring for self-training pipelines

- Sectors: AI quality assurance, compliance, platform governance

- Tools/workflows: track n-gram diversity, output length, and difficulty curves; add repetition penalties; measure anchor-alignment via embeddings; trigger interventions when metrics degrade

- Assumptions/dependencies: metric instrumentation; thresholds and playbooks for corrective actions

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Lightweight safety anchoring during self-improvement

- Sectors: general consumer AI, enterprise assistants, platform safety

- Tools/workflows: seed the anchor pool with safety-critical exemplars (e.g., refusal patterns, red-teaming cases); few-shot grounded generation to regularize self-play

- Assumptions/dependencies: breadth and quality of safety anchors; post-hoc safety evaluation and red-teaming remain necessary

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Rapid, low-cost academic experimentation on reasoning

- Sectors: academia, nonprofit research labs

- Tools/workflows: reproduce self-evolution studies with open base models and ≤5% anchor sets; analyze co-evolution dynamics and ablate curriculum/grounding components

- Assumptions/dependencies: modest compute; small but representative anchor sets; access to open RL training stacks

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Test case and unit-test synthesis at mid-difficulty

- Sectors: software engineering, QA automation

- Tools/workflows: anchored generation of balanced test cases; filter by solver uncertainty to avoid trivial/unsolvable tests; integrate into CI pipelines

- Assumptions/dependencies: verifiable code execution oracles; domain anchors (APIs, specs) to avoid drift

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Helpdesk and FAQ expansion from small seed corpora

- Sectors: customer support, IT service desks, internal enablement

- Tools/workflows: ground generation on a small set of approved FAQs/KBs; curate mid-uncertain items for human review before publishing

- Assumptions/dependencies: accurate seed content; human QA loop for approval; change-management to avoid misinformation

- Application type: Immediate Application

- Personalized tutoring and exam prep at the “right” difficulty

- Sectors: education, professional certification

- Tools/workflows: generate problem sets anchored by exemplar solutions; select mid-uncertain items to match learner ability; include rationales/solutions

- Assumptions/dependencies: dependable correctness checks (programmatic judges or vetted answer keys); controls against spurious difficulty inflation

- Application type: Immediate Application

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities will benefit from further research into verifiers for open-ended tasks, safety, scalability, and governance.

- Self-maintaining enterprise assistants that continuously upskill with minimal labels

- Sectors: enterprise IT, customer support, sales ops

- Tools/workflows: ingest production logs; mine small anchor corrections; run periodic anchored self-play with online curriculum

- Assumptions/dependencies: privacy-preserving data pipelines; robust drift detection; strong governance/audit trails

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Clinical and legal reasoning systems with anchored self-evolution

- Sectors: healthcare, law

- Tools/workflows: seed with guidelines/precedents as anchors; integrate formal or semi-formal verifiers (checklists, structured templates); human oversight checkpoints

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous validation and regulatory approval; high-stakes safety and bias controls; better semantic verifiers for non-numeric tasks

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Public-sector and low-resource language reasoning assistants

- Sectors: education policy, digital government, NGOs

- Tools/workflows: small, high-quality local-language anchors; anchored self-play to bootstrap reasoning skills with limited labels

- Assumptions/dependencies: culturally appropriate anchors; local evaluation standards; community review processes

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Scientific discovery and formal reasoning (e.g., theorem proving)

- Sectors: academia, R&D, advanced engineering

- Tools/workflows: anchors from proof corpora; self-generated conjectures with solver attempts; formal proof checkers as verifiers

- Assumptions/dependencies: mature formal verification tooling; scalable generation without diversity collapse; compute for long horizons

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Robotics and embodied agents with anchored task curricula

- Sectors: robotics, manufacturing, logistics

- Tools/workflows: few-shot anchors from human demonstrations; simulator-based verifiers; curriculum of mid-uncertain tasks for skill acquisition

- Assumptions/dependencies: high-fidelity simulators; safe sim-to-real transfer; multi-modal extensions of R-Few

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Planning and optimization agents in finance and energy

- Sectors: finance (portfolio/risk), energy (grid operations)

- Tools/workflows: anchors from standards and playbooks; environment/simulator rewards as verifiers; mid-uncertainty gating to avoid overfitting extremes

- Assumptions/dependencies: trusted simulators; governance over model decisions; robust stress testing

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- “Anchor-guided self-play RL” as an MLOps product category

- Sectors: AI platforms, ML tooling vendors

- Tools/workflows: turnkey pipelines for anchor curation, challenger generation, curriculum filtering, monitoring dashboards for diversity/length/difficulty and drift

- Assumptions/dependencies: standard interfaces to RL stacks and verifiers; demand for data-lean post-training; interoperability with enterprise governance tools

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Standards and governance for anchored self-evolution

- Sectors: regulators, industry consortia, compliance

- Tools/workflows: audit requirements for anchor pools; documentation of curriculum policies and drift metrics; test suites for collapse/reward-hacking detection

- Assumptions/dependencies: sector-wide consensus on metrics; shared benchmarks and audits; alignment with existing AI risk frameworks

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Multimodal extension to vision-LLMs and agents

- Sectors: autonomous systems, medical imaging, retail

- Tools/workflows: small multimodal anchor sets; extend R-Few to image/video tasks; simulator or task-specific verifiers

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable multimodal verifiers; curated anchors with licensing clarity; compute for long-context training

- Application type: Long-Term Application

- Open-ended creative assistants with semantic anchors

- Sectors: media, design, marketing

- Tools/workflows: anchor styles/brand guidelines; curriculum on “novel yet aligned” generations; human preference feedback to refine verifiers

- Assumptions/dependencies: better proxies for creativity and quality; IP and rights management; reduced susceptibility to verbosity-based hacks

- Application type: Long-Term Application

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Larger base models benefit more from R-Few; capacity limitations may reduce gains for small models.

- Tasks with clear, verifiable correctness (math, code, structured QA) see the most reliable improvements; open-ended tasks will need stronger verifiers or human-in-the-loop checkpoints.

- Quality and diversity of anchor data are critical; poor anchors can encode biases or misguide evolution.

- Monitoring for diversity collapse and verbosity-based reward hacking remains necessary, even with anchoring.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.