Achieving Olympia-Level Geometry Large Language Model Agent via Complexity Boosting Reinforcement Learning

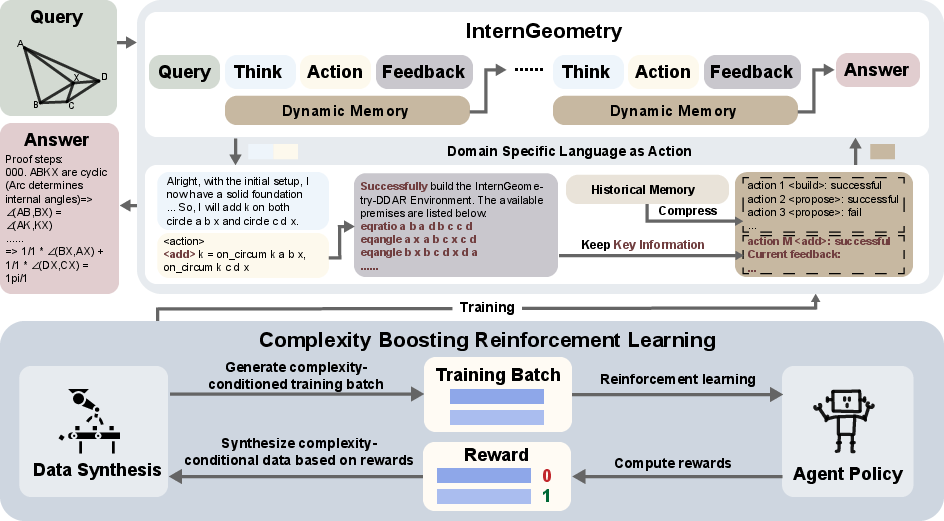

Abstract: LLM agents exhibit strong mathematical problem-solving abilities and can even solve International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) level problems with the assistance of formal proof systems. However, due to weak heuristics for auxiliary constructions, AI for geometry problem solving remains dominated by expert models such as AlphaGeometry 2, which rely heavily on large-scale data synthesis and search for both training and evaluation. In this work, we make the first attempt to build a medalist-level LLM agent for geometry and present InternGeometry. InternGeometry overcomes the heuristic limitations in geometry by iteratively proposing propositions and auxiliary constructions, verifying them with a symbolic engine, and reflecting on the engine's feedback to guide subsequent proposals. A dynamic memory mechanism enables InternGeometry to conduct more than two hundred interactions with the symbolic engine per problem. To further accelerate learning, we introduce Complexity-Boosting Reinforcement Learning (CBRL), which gradually increases the complexity of synthesized problems across training stages. Built on InternThinker-32B, InternGeometry solves 44 of 50 IMO geometry problems (2000-2024), exceeding the average gold medalist score (40.9), using only 13K training examples, just 0.004% of the data used by AlphaGeometry 2, demonstrating the potential of LLM agents on expert-level geometry tasks. InternGeometry can also propose novel auxiliary constructions for IMO problems that do not appear in human solutions. We will release the model, data, and symbolic engine to support future research.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Easy-to-Read Summary of “Achieving Olympia-Level Geometry LLM Agent via Complexity Boosting Reinforcement Learning”

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces InternGeometry, a smart AI “agent” designed to solve very hard geometry problems—like the ones from the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO). Unlike earlier systems that need massive amounts of training data and heavy search, InternGeometry learns to think step-by-step, try ideas, check them with a strict math tool, remember what worked, and keep going until it finds a full proof.

Main Topic and Purpose

The authors aim to show that a LLM can reach medal-winning performance in Olympiad-level geometry by:

- Thinking in steps (like a student explaining their work)

- Proposing helpful extra constructions (like drawing new lines or points)

- Checking each idea with a formal geometry engine (a strict proof checker)

- Learning from easier to harder problems over time

Their system, InternGeometry, solves 44 out of 50 IMO geometry problems from 2000–2024, using only a tiny amount of training data compared to older systems.

Key Questions the Paper Tries to Answer

- Can an LLM agent (not just a fixed “expert” model) solve very difficult geometry problems efficiently?

- How can an AI discover “auxiliary constructions” (extra points/lines/circles that make a proof work) when there aren’t clear rules for which ones to try?

- What training method helps the AI get better fast without huge datasets?

- Do long, multi-step interactions and smarter practice (starting easy and getting harder) really improve results?

How the System Works (Explained Simply)

The core loop: Think → Act → Check → Learn

Imagine a student solving a geometry problem:

- Think: The AI writes down its reasoning in plain language (“Maybe angle A equals angle B…”).

- Act: It turns that idea into a precise instruction in a special “geometry code” (a domain-specific language, or DSL).

- Check: A formal geometry engine (like a super strict math referee) verifies whether the idea is correct or the construction is valid.

- Learn: Based on the feedback, the AI adjusts its next move.

This loop repeats—often more than 200 times per problem—until the whole proof is done.

What are “auxiliary constructions”?

They’re helpful extra pieces (like drawing a new line or adding a point on a circle) that aren’t in the original problem but make hidden relationships visible. Humans use them all the time in Olympiad solutions. They’re hard to guess because there’s no simple rule for which one to add.

The geometry engine: a strict checker

InternGeometry uses an interactive proof engine (built on an open-source system called Newclid). It stores all facts learned so far and:

- Checks claims (propositions) the AI makes

- Verifies constructions are valid

- Confirms when a full proof is complete

Memory that keeps things tidy

Because the AI may try hundreds of steps, it uses a “dynamic memory” to summarize the history: what it tried, what worked, and what didn’t—like a neat notebook that keeps only the important parts. This helps it focus and prevents repeating mistakes.

Avoiding loops and getting stuck

The system has simple rules to reject repeated or unhelpful actions (like doing the same thing over and over). This keeps the exploration fresh.

How it learns: from easy to hard (CBRL)

The training process is like a video game with levels:

- Cold start: The AI practices on ~7,000 easier problems so it learns how to use the tool and format.

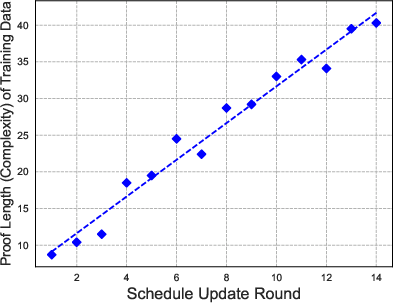

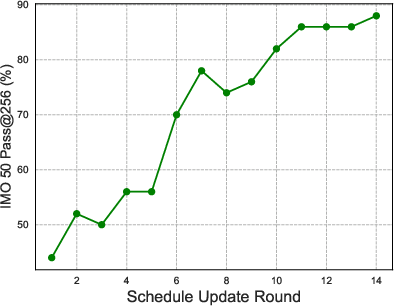

- Complexity-Boosting Reinforcement Learning (CBRL): The system automatically creates practice problems with a chosen difficulty and gradually increases the challenge. “Difficulty” here means how many proof steps are needed.

- Rewards: The AI gets credit when:

- A step is useful (e.g., a proposed claim is proven true, or a construction helps in the final proof)

- The whole problem is solved

- This simple reward (1 for success, 0 for failure) keeps the scoring clear and automatic.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here are the most important results:

- Medal-level performance: InternGeometry solved 44 out of 50 IMO geometry problems (2000–2024), beating top systems like AlphaGeometry 2 (42/50) and SeedGeometry (43/50).

- Tiny training data: It used only about 13,000 training examples—around 0.004% of the data used by AlphaGeometry 2. That means it’s very data-efficient.

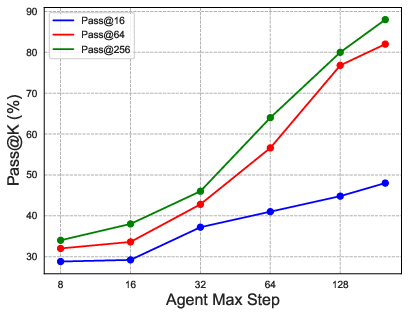

- Long, patient reasoning helps: Allowing the AI to take many steps (and remember them well) makes a big difference. Increasing the number of steps helps more than just trying many short attempts.

- Smarter practice matters: The “easy-to-hard” training schedule (CBRL) works better than training only on easy problems, only on hard problems, or mixing everything randomly. The curriculum helps the AI steadily build skills.

- Creative constructions: In some cases, the AI invented new auxiliary constructions that don’t appear in human solutions—showing hints of creativity.

Why this is important:

- It shows LLM agents can tackle highly structured, creative math tasks—not just routine calculations.

- It reduces the need for massive datasets and heavy search, making advanced geometry solving more accessible.

- It opens the door to AI systems that explore, reflect, and build proofs in a human-like way.

What This Could Mean for the Future

- Better math assistants: Similar agents could help students and researchers explore complex proofs and check their work step-by-step.

- More general reasoning: The same “Think → Act → Check → Learn” pattern can be used in other subjects that need many steps and careful checking (like programming, science experiments, or formal logic).

- Shared tools for progress: The authors plan to release the model, the training data, and the geometry engine, which can speed up future research.

In short, InternGeometry shows that with patient step-by-step thinking, good memory, and practice that gets harder over time, an AI can reach Olympiad-level geometry performance—using surprisingly little data and even discovering new ideas along the way.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a concise list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions. Each point is concrete and intended to guide future research.

- Coverage and expressivity of the symbolic engine: InternGeometry-DDAR claims a “rich theorem library” and advanced point placement, but lacks a precise inventory of supported theorems, constructions, and inference rules; no formal analysis quantifies which IMO problem classes (e.g., trigonometric, complex-number, coordinate methods) fall outside its expressivity.

- Handling non–pure-geometry computations: Unsolved IMO problems are attributed to tasks “beyond pure geometric proof,” but the paper does not prototype or evaluate hybrid pipelines (e.g., trig/complex/coordinate geometry modules, CAS integration) that could close this gap.

- Validity and robustness of global point placement: “Globally optimizing point placements” to satisfy constraints is mentioned without formal guarantees (e.g., avoidance of degenerate configurations, uniqueness/existence, stability); empirical failure modes and correctness checks are not reported.

- Complexity metric validity: Difficulty is defined by DDAR proof step count, but the paper does not validate this metric’s robustness across engines or its correlation with human difficulty labels, nor test whether optimizing for this metric generalizes to real competitions beyond IMO 50.

- Curriculum selection mechanism: The CBRL schedule updates difficulty to maximize average absolute advantage, yet the exact algorithm (e.g., estimator variance, sensitivity to α and ε, update stability, exploration/exploitation balance) is not benchmarked against alternative curricula (self-play, bandit allocation, teacher-student scheduling).

- Reward design and credit assignment: Binary outcome and step-effectiveness rewards may be too coarse for long-horizon credit assignment; the paper does not study shaped rewards (e.g., subgoal coverage, proof minimality, construction usefulness), temporal-difference learning, or variance-reduction strategies.

- Sensitivity to RL hyperparameters: Optimization details (KL regularization β, clip ε, batch sizes, rollout lengths) are under-specified; no hyperparameter sensitivity or stability analysis (e.g., gradient norms, collapse frequency, catastrophic forgetting) is provided.

- Rejection sampling policy risks: The rule-based PassCheck may prune valid repeated or formatting-adjacent actions necessary for complex proofs; there is no quantitative analysis of false rejections, diversity impacts, or comparisons to alternatives (e.g., novelty bonuses, entropy regularization, tree search).

- Memory compression fidelity: The dynamic memory module compresses hundreds of turns but lacks metrics on information retention, error rates (mis-summarization, omission of critical facts), and ablations across compression strategies (learned summarizers, key-value memory, retrieval augmentation).

- Generalization scope: Results focus on Euclidean IMO 50 (+IMO 2025); the agent is not evaluated on other geometry domains (projective, non-Euclidean, 3D) or benchmarks (e.g., geometry in other olympiads), leaving transfer and domain breadth unexplored.

- Compute and efficiency reporting: Pass@256 with 200-step trajectories suggests substantial inference cost; the paper does not provide wall-clock budgets, GPU/CPU utilization, memory footprints, or standardized comparisons to search-tree ensembles for a fair compute-normalized benchmark.

- Single-run reliability and variance: Performance variance across seeds, temperatures, and top-p settings is not reported; robustness to stochasticity and reproducibility (confidence intervals, bootstrap) are missing.

- Proof quality assessment: Success is binary (target proven), with no evaluation of proof minimality, readability, redundancy, or alternative derivations; human-in-the-loop assessment or automated proof-quality metrics are absent.

- Data leakage and deduplication checks: The cold-start 7K formalized data and 6K synthesized problems may overlap conceptually with IMO 50; the paper does not present deduplication, overlap audits, or provenance to guarantee no test contamination.

- Synthetic data priors: The statistical priors used to add auxiliary constructions are not described; distribution mismatch risks (e.g., overuse of certain constructions, missing rare motifs) and validation against real problem distributions are unaddressed.

- Failure analysis granularity: The paper notes remaining unsolved problems but does not categorize failure modes (engine limitations vs. agent planning errors vs. action collapse), nor provide targeted interventions for each failure class.

- Subgoal proposal heuristics: How the agent chooses which propositions to test is unspecified; there is no analysis of subgoal selection quality, redundancy, or learning signals that encourage informative subgoals versus trivial ones.

- Interaction length limits: The agent caps at 200 steps; there is no study of diminishing or increasing returns beyond 200, adaptive step budgets per problem, or termination criteria that balance exploration and efficiency.

- Comparative RL baselines: CBRL is not compared against alternative RL formulations (e.g., policy gradient with learned reward models, Monte Carlo tree search, self-play curriculum); ablations show benefit but not optimality versus strong baselines.

- Multimodality with diagrams: The agent relies on DSL and textual interaction; the potential of integrating diagram understanding or visual grounding (image-based figure parsing, layout constraints) is not explored.

- Engine feedback interpretation: The agent “reflects” on engine feedback, but misinterpretation rates, feedback salience, and mechanisms to prevent confirmation bias or overfitting to unverifiable subgoals are unmeasured.

- Robust parsing and DSL errors: Parser resilience to malformed or near-miss actions, recovery strategies, and impacts on success/failure rates (e.g., retry policies) are not quantified.

- Proof search vs. agent planning: There is no controlled comparison to search-heavy methods (e.g., MCTS, beam search) using the same engine, making it hard to isolate the value of agentic planning versus formal search improvements.

- Release readiness and reproducibility: The paper promises release of model/data/engine, but without current artifact availability, reproducibility, benchmarking scripts, and exact configs remain open.

- Ethical and safety considerations: No discussion on responsible use, potential bias in synthesized problems, or safeguards against producing fallacious but formally accepted proofs due to engine limitations.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by adapting the paper’s released model, data, and symbolic engine, or by reusing its agent design, memory, and CBRL training workflow.

- Sector: Education — Adaptive Geometry Tutor and Problem Generator

- Application: Deploy an LLM-powered tutor that interactively guides students through formal geometric proofs, proposes auxiliary constructions, and provides step-level feedback; auto-generate practice sets with controlled difficulty via CBRL.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Classroom LMS plugins; “Problem Studio” for teachers; student-facing app combining Think→Action (DSL)→Feedback; auto-grading with binary step rewards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Difficulty metric (DDAR proof steps) correlates with human difficulty; robust mapping from natural-language problems to the DSL; guardrails for correctness and pedagogical alignment.

- Sector: Academia — Research Assistant for Geometric Proof Exploration

- Application: Use InternGeometry to explore alternative proofs and novel auxiliary constructions for olympiad-level geometry, assess theorem coverage, and generate new conjectures.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Proof Explorer” notebooks integrating InternGeometry-DDAR; corpus-building of alternative proofs; automated ablation studies on construction strategies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Engine’s theorem library coverage is adequate for the target problem class; human oversight for mathematical novelty claims.

- Sector: Software (Reasoning Systems) — CBRL Trainer for Tasks with Controllable Difficulty

- Application: Repurpose the Complexity-Boosting RL (CBRL) pipeline for other reasoning tasks where synthetic data can be generated with adjustable difficulty (e.g., code challenges with graded test complexity, logic puzzles).

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “CBRL Trainer” SDK; difficulty schedulers that maximize advantage; binary step/outcome rewards with automatic computation rules.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Existence of an automatic difficulty proxy that correlates with learning progress; feasible synthetic-data generation; reliable reward computation.

- Sector: Software/DevTools — Long-Horizon Agent Framework with Dynamic Memory

- Application: Integrate the Think→DSL Action→Feedback loop, dynamic memory compression, and rejection sampling into agent frameworks for complex tool use (e.g., multi-step data analysis, configuration reasoning).

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Agent libraries providing memory manager modules (𝔚), action checkers (PassCheck), and long-horizon inference settings; deployment with standardized DSLs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Tool interfaces must support formal action execution and rich feedback; sufficient context window and latency tolerance for 100–200+ turn interactions.

- Sector: Education/Content — Geometry Content Authoring and Auto-Formalization

- Application: Convert existing geometry problems into formal DSL, generate diverse proof trajectories, and assemble curated datasets for textbooks, contests, and MOOCs.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Formalizer” service (fine-tuned LLM) plus Newclid-based checking; editorial dashboard to vet generated content.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Quality control by domain experts; coverage of problem formats (including multi-part questions and figure references).

- Sector: Software/CAD-lite — Geometry Constraint Checker for 2D Diagrams

- Application: Validate basic Euclidean constraints (e.g., collinearity, angle equality, similarity) in schematic drawings and propose minimal auxiliary constructions to restore feasibility.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Plug-in to vector graphics or simple CAD tools; DSL translation layer; interactive constraint repair suggestions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Input diagrams must be convertible to the DSL; engine currently focuses on pure geometric proof without tolerances or projective effects.

- Sector: Assessment — Automated Scoring of Geometry Problem Solving

- Application: Use binary step effectiveness and outcome rewards to score student solutions or model-generated trajectories, enabling consistent and transparent evaluation.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Scoring APIs integrated into online testing; trajectory logging and audit trails; feedback reports by proof phase.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Formalization fidelity of student solutions; alignment of reward definitions with rubric; robustness to partial-credit policies.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling the theorem library and DSL, expanding beyond pure Euclidean proof, or integrating domain-specific toolchains and regulations.

- Sector: CAD/CAE and Mechanical Engineering — Formal Co-Prover for Design Verification

- Application: Verify geometric constraints in mechanical linkages, assemblies, and parametric models; propose auxiliary features or constraints to satisfy design intents; produce auditable proofs.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CAD plug-ins connecting InternGeometry-DDAR to model kernels; “Proof Ledger” for design compliance; change-impact analyses tied to proof states.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Richer theorem libraries (projective geometry, constraints with tolerances), robust CAD-to-DSL translation, performance at industrial scale, certification-grade auditability.

- Sector: Architecture/Civil Engineering — Geometric Compliance and Layout Optimization

- Application: Formally validate structural alignments, angles, and clearances; assist in layout optimization using creative auxiliary constructions; reduce design iteration risk.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: BIM integrations; constraint-driven layout assistant; proof-based compliance reports for permitting and code checks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Extension to tolerances, measurement uncertainty, and building codes; mixed numerical–symbolic pipelines.

- Sector: Robotics — Motion Planning with Formal Geometric Constraints

- Application: Long-horizon agents that interact with physics/geometry solvers to propose and verify collision-free constructions (waypoints, corridors), using CBRL to scale from easy to complex environments.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Planner RL Platform” with difficulty schedulers (e.g., obstacle density, path length); dynamic memory for multi-turn plan refinement; simulator integrations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable difficulty proxies for planning tasks; safe reward shaping; generalization from symbolic proofs to continuous control.

- Sector: Computer Vision/AR/VR — Formal Calibration and Multi-View Geometry Co-Prover

- Application: Assist with epipolar/homography constraints and calibration proofs for multi-camera rigs; propose auxiliary correspondences to meet geometric conditions and verify consistency.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Calibration Co-Prover” integrated with vision toolchains; diagram-to-DSL converters for feature geometry; proof-backed calibration QA.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Expansion from Euclidean/DDAR to projective geometry; robust handling of noise, uncertainty, and real-world data.

- Sector: Medical Imaging/Surgical Planning — Geometric Constraint Validation

- Application: Validate geometric relationships in patient-specific models (e.g., alignment angles, distances, trajectories), with formal proofs supporting planning decisions and device placement.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Imaging-to-DSL translators; surgical path co-prover; compliance logs for clinical review.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulatory requirements; handling of measurement uncertainty; integration with anatomical modeling tools.

- Sector: EDA (Electronic Design Automation) — Geometric Routing and Layout Proofs

- Application: Prove geometric constraints for routing, spacing, and symmetry in chip layout; propose auxiliary constructions to resolve violations.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: EDA plug-in with formal geometry checks; proof traceability for tape-out signoff; CBRL-trained agents for progressive design tasks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: DSL alignment with layout objects; large-scale performance; integration with existing DRC/LVS systems.

- Sector: Energy/Infrastructure — Formal Layout Optimization (PV, Wind Farms, Grids)

- Application: Verify geometric siting constraints (clearances, orientations), optimize placements with formal proofs ensuring compliance and performance.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: GIS/engineering integrations; constraint co-prover for infrastructure planning; audit-ready proof artifacts.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Mixed discrete–continuous modeling; environmental uncertainty; domain-specific constraint libraries.

- Sector: Finance (Methodology Transfer) — Curriculum RL for Complex Analytical Tasks

- Application: Apply CBRL to train agents in tasks with measurable difficulty (e.g., scenario analysis with increasing constraints), improving training data efficiency and convergence.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “CBRL for Analytics” platform; difficulty proxies (constraint count, plan length); binary step/outcome reward rules.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Valid difficulty metrics; reliable synthetic task generation; strong guardrails to avoid overfitting proxy measures.

- Sector: Standards and Policy — AI-Assisted Formal Verification Guidelines

- Application: Develop frameworks for certifying AI-generated geometric proofs in safety-critical domains; define audit requirements, reproducibility standards, and acceptable theorem libraries.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Policy templates; proof audit pipelines; compliance testing suites leveraging released models/engines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cross-industry consensus; mature toolchains; clear liability and traceability norms.

- Sector: Multimodal AI — Diagram-to-DSL Translators for Agentic Proofs

- Application: Build vision-language modules that extract geometric entities and constraints from diagrams to automatically produce DSL inputs, enabling end-to-end diagram-proof workflows.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Diagram2DSL” model; joint training with symbolic feedback; curriculum scheduling by visual complexity.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-accuracy visual parsing; robust grounding between visual entities and formal symbols.

- Sector: Mathematical Discovery — Agentic Exploration of New Geometric Constructions

- Application: Use the agent’s creativity to search for previously unseen auxiliary constructions and proof strategies; catalog candidate theorems for human validation.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Discovery pipelines with human-in-the-loop validation; repositories of alternative proofs and constructions; meta-analysis of heuristic patterns.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Expert vetting; ensuring correctness beyond engine coverage; credit and attribution frameworks.

- Sector: Enterprise Workflows — Memory-Enhanced Agents for Complex Tool Use

- Application: Generalize dynamic memory and rejection sampling to enterprise agents that orchestrate multi-step toolchains (e.g., data wrangling, reporting, compliance checks) with hundreds of interactions.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Memory manager modules; action-quality filters; long-horizon inference orchestration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Tool APIs that return structured feedback; latency/cost budgets for long trajectories; governance for agent autonomy.

Glossary

- Advantage: In reinforcement learning, a measure of how much better an action or step performs compared to the average; used to weight policy updates. "represents the advantage at step of the -th trajectory within a batch of samples."

- AlphaGeometry 2: A state-of-the-art expert system for automated geometry theorem proving that relies on large-scale synthetic data and search. "AI for geometry problem solving remains dominated by expert models such as AlphaGeometry 2"

- Angle chasing: A classical geometric technique that deduces unknown angles using known angle relations and theorems. "via an elegant geometric construction using classical angle chasing and basic theorems."

- Auxiliary constructions: Additional geometric elements (points, lines, circles) introduced to make a proof possible or simpler. "contains creative auxiliary constructions that have weak heuristics and require multiple trials"

- Beam search: A heuristic search strategy that explores a fixed-size set of the most promising candidates at each step. "ensembles of beam search"

- Chain-of-thought reasoning (slow thinking): Step-by-step natural-language reasoning produced by an LLM to structure problem solving. "where denotes the slow chain-of-thought reasoning"

- Cold-start phase: An initial training stage before reinforcement learning, typically using supervised fine-tuning to establish baseline behavior. "Before reinforcement learning begins, there is a cold-start phase in which we perform supervised fine-tuning"

- Complexity-Boosting Reinforcement Learning (CBRL): A curriculum-based RL framework that progressively increases synthesized problem difficulty to accelerate learning. "we introduce Complexity-Boosting Reinforcement Learning (CBRL), which gradually increases the complexity of synthesized problems across training stages."

- Curriculum RL: Reinforcement learning organized from simpler to harder tasks to improve convergence and generalization. "a multi-stage curriculum RL pipeline"

- Data synthesis pipeline: An automated process that generates training tasks/problems with controllable properties such as difficulty. "we build a data synthesis pipeline that can generate geometry tasks with a specified complexity (e.g., required proof steps)."

- Deductive database arithmetic reasoning (DDAR): A symbolic reasoning framework that exhaustively applies geometric theorems to derive all conclusions from known facts. "a deductive database arithmetic reasoning (DDAR) system is employed to exhaustively search for theorems"

- Domain-specific language (DSL): A specialized language tailored to define geometric configurations and actions for the proof engine. "domain-specific language (DSL)"

- Dynamic memory: An interaction-level mechanism that compresses multi-turn histories to retain essential actions and outcomes, enabling long-horizon reasoning. "A dynamic memory module compresses the multi-turn interaction history to preserve essential actions and outcomes."

- Formal language: Precisely structured syntax used to express constructions and propositions for verification by a proof engine. "verify those ideas in the symbolic engine with formal language"

- Formal proof systems: Software frameworks that check proofs rigorously using formal logic and typed languages. "with the assistance of formal proof systems"

- GRPO: A policy-gradient training rule with ratio clipping used in recent RL for reasoning tasks. "Following GRPO \citep{2024DeepSeekMath}, given task , the training gradient is:"

- Interactive Theorem Provers (ITPs): Systems allowing users or agents to construct and verify formal proofs interactively. "Interactive Theorem Provers (ITPs) specialized for mathematics"

- InternGeometry-DDAR: The interactive geometric proof engine built on a DDAR backend and extended with richer definitions and interactive state. "we build InternGeometry-DDAR, an interactive geometric proof engine based on the open-source DDAR system Newclid"

- Inversion: A geometric transformation with respect to a circle, often used to simplify complex configurations. "while most human solvers relied on inversion, trigonometry or complex numbers"

- Isogonal conjugate: A pair of points related by symmetric reflection of lines around angle bisectors in polygons (or triangles). "These two points form an isogonal conjugate pair in quadrilateral "

- KL divergence: A measure of divergence between probability distributions, used as a regularizer in policy optimization. " is the KL divergence, used as a regularizer to constrain optimization of the agent model."

- Lean (proof assistant): A formal proof assistant used for constructing and checking mathematical proofs. "LEAN \citep{moura2021lean}"

- Newclid: An open-source DDAR-based geometry system used as the foundation for the interactive proof engine. "based on the open-source DDAR system Newclid~\citep{sicca2024newclid}."

- Pass@K: An evaluation metric indicating whether at least one of K sampled solutions succeeds. "During the test, the pass@K is set to 256."

- Prior-guided rejection sampling: An inference-time sampling approach that rejects repetitive or low-quality actions based on rules or priors. "as well as a prior-guided rejection sampling method for ."

- Propositions: Candidate statements or subgoals proposed during a proof to be verified by the engine. "continuously propose propositions or auxiliary constructions"

- SeedGeometry: A recent expert-model-based geometry prover used as a baseline. "We use AlphaGeometry 2 \citep{chervonyi2025gold} and SeedGeometry \citep{chervonyi2025gold} as our baselines"

- Symbolic engine: A tool that manipulates formal symbolic representations to verify constructions and propositions. "verifying them with a symbolic engine"

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT): Training on labeled data to align model outputs with desired behavior before RL. "The supervised fine-tuning objective is:"

- Test-time scalability: The property that performance can improve by increasing sampling or interaction budget at inference. "indicating the test-time scalability of InternGeometry."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.