From Entropy to Epiplexity: Rethinking Information for Computationally Bounded Intelligence

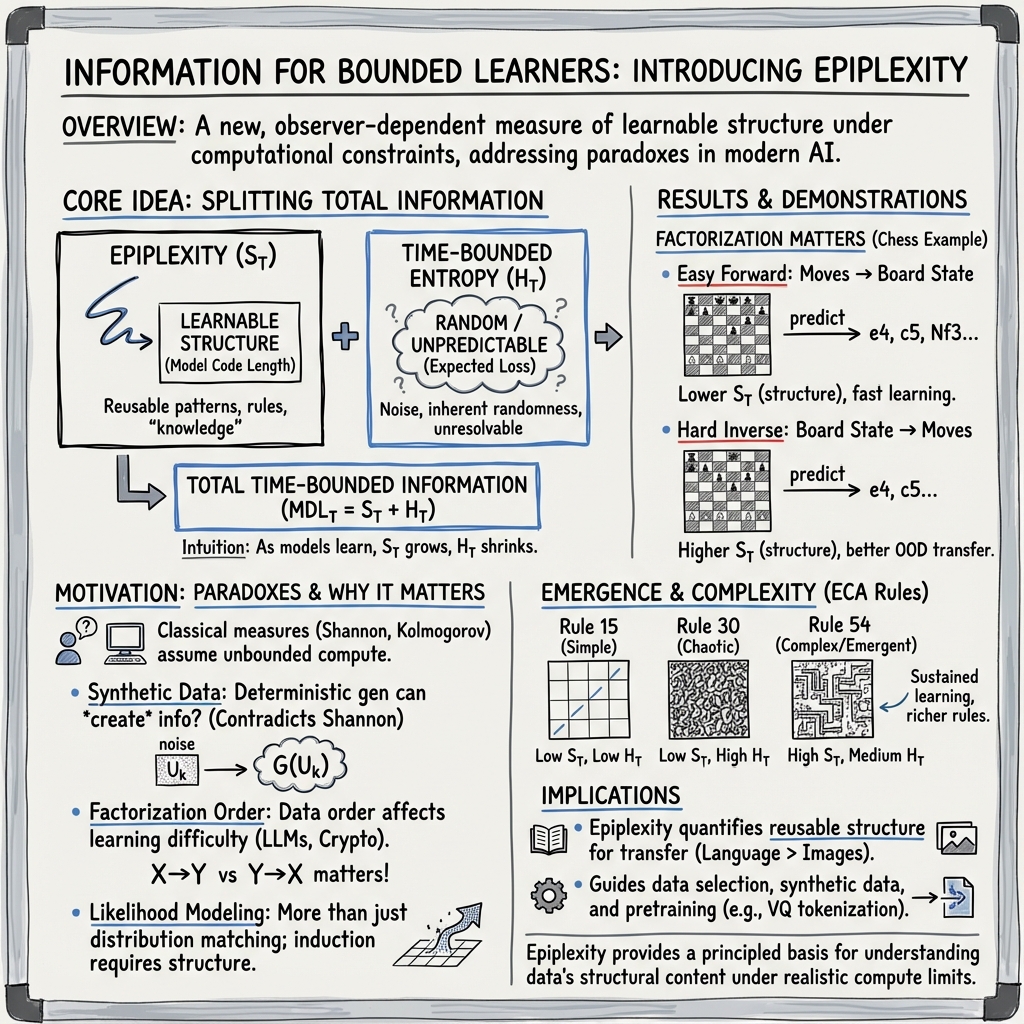

Abstract: Can we learn more from data than existed in the generating process itself? Can new and useful information be constructed from merely applying deterministic transformations to existing data? Can the learnable content in data be evaluated without considering a downstream task? On these questions, Shannon information and Kolmogorov complexity come up nearly empty-handed, in part because they assume observers with unlimited computational capacity and fail to target the useful information content. In this work, we identify and exemplify three seeming paradoxes in information theory: (1) information cannot be increased by deterministic transformations; (2) information is independent of the order of data; (3) likelihood modeling is merely distribution matching. To shed light on the tension between these results and modern practice, and to quantify the value of data, we introduce epiplexity, a formalization of information capturing what computationally bounded observers can learn from data. Epiplexity captures the structural content in data while excluding time-bounded entropy, the random unpredictable content exemplified by pseudorandom number generators and chaotic dynamical systems. With these concepts, we demonstrate how information can be created with computation, how it depends on the ordering of the data, and how likelihood modeling can produce more complex programs than present in the data generating process itself. We also present practical procedures to estimate epiplexity which we show capture differences across data sources, track with downstream performance, and highlight dataset interventions that improve out-of-distribution generalization. In contrast to principles of model selection, epiplexity provides a theoretical foundation for data selection, guiding how to select, generate, or transform data for learning systems.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a simple but deep question: what useful patterns can a realistic, time-limited learner (like a computer program or a student) actually pick up from data? Classic information theory often assumes an all-powerful observer with unlimited time and memory. But real learners aren’t like that. To fix this mismatch, the authors propose a new way to measure the learnable, useful structure in data for a computationally bounded observer. They call this new measure epiplexity (short for “epistemic complexity”), and they pair it with time-bounded entropy, which captures the random, unlearnable part.

Key Objectives

The paper focuses on three puzzles (the authors call them “paradoxes”) that arise when you view information with unlimited power, but that don’t match what we see in practice:

- Can deterministic computation “create” new useful information? In practice it seems yes (e.g., synthetic data helps models), but classic theory says no.

- Does the order of data matter? In practice yes (e.g., LLMs learn better left-to-right), but classic theory says total information doesn’t change with order.

- Is modeling by maximizing likelihood “just” copying the data distribution? In practice no—models often learn extra structure and abilities—yet classic theory can make it seem that way.

The goal is to define and measure a kind of information that lines up with modern machine learning: how much structure a time-limited learner can extract and store.

Methods and Core Ideas

To make the ideas accessible, think of learning data like learning a puzzle:

- Some parts are pattern-like and learnable (e.g., a recipe or rules of a game).

- Some parts are effectively random to you if you don’t have enough time or the secret key (like a good magic trick).

The paper formalizes this split for realistic observers:

- Epiplexity: how many “instructions” (bits) a time-limited learner needs to store to capture the patterns in the data. This is the structured, reusable knowledge.

- Time-bounded entropy: how many extra “instructions” are still needed to describe the leftover, unpredictable part, given the learned model.

They base the split on a simple principle called Minimum Description Length (MDL): the best explanation for data is the one that gives the shortest total description = bits to describe the model + bits to describe the data using that model. In everyday terms: a shorter, smarter “recipe” for the data is better.

Crucially, everything is done under a time limit. That’s what makes this observer realistic: the model must run in a bounded time. Under this constraint, some sequences that are simple for all-powerful beings still look random to us.

How do they estimate this in practice? They use neural networks:

- Train a model to predict data and watch its “loss curve” (how surprised it is as it learns). Roughly, the area under the curve can be used to estimate how much structure the model is absorbing versus how much randomness it can’t beat.

- They also use teacher–student setups and compare predictions to estimate how much learnable structure transfers.

These procedures give practical estimates of epiplexity (structure learned) and time-bounded entropy (unpredictable leftovers) for real datasets and models.

Main Findings

Here are the main takeaways, summarized in everyday language:

- Deterministic computation can “create” useful information for time-limited learners. For example, running simple rules over time (like in Conway’s Game of Life) produces emergent objects and patterns. To an all-powerful being, nothing “new” was created. But to a time-limited learner, these are new, useful patterns to model—so epiplexity goes up.

- Data order can matter a lot. Even with the same set of sentences, training left-to-right versus right-to-left can change how well a model learns. Classic theory says total information is the same either way, but epiplexity recognizes that some orders make patterns easier for a time-limited learner to extract.

- Likelihood modeling is more than distribution matching. When a model maximizes likelihood, it can build internal programs—circuits or routines—that go beyond the obvious recipe that generated the data. In chaotic or emergent systems, a time-limited learner benefits from discovering higher-level patterns (like species of moving objects in Game of Life) that weren’t explicit in the simple rules. That extra structure shows up as higher epiplexity.

- Pseudorandom sequences look random (and unlearnable) to time-limited learners. If you don’t know the secret seed, a cryptographically secure pseudorandom generator produces outputs that are unpredictable for any practical algorithm. The paper’s measure agrees: high time-bounded entropy (lots of randomness), almost zero epiplexity (no learnable structure).

- There exist datasets with growing epiplexity. Under reasonable assumptions, the authors show there are data distributions whose structural content (learnable by realistic observers) increases with size—not just a constant trickle. This matches the idea that bigger, richer datasets can teach models more reusable structure.

- Measuring epiplexity tracks real-world performance. Their estimates distinguish data sources, correlate with downstream results, and highlight dataset tweaks (like smarter ordering) that improve out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. In short, higher epiplexity data tends to help models transfer better to new tasks.

Implications and Impact

This work shifts focus from “which model should I use?” to “which data should I use (or generate) to teach the model the most reusable structure?” That is:

- Epiplexity provides a foundation for data selection: choosing, generating, and ordering data to maximize learnable structure for a time-limited learner.

- It explains why synthetic data, careful data ordering, and emergent processes can be powerful—even if classic theory says “no new information.”

- It clarifies why some datasets (like diverse text) transfer better than others: they pack more learnable structure per example for realistic learners.

- It helps separate noise from signal: pseudorandom “surprise” doesn’t help you build useful circuits; structure does.

Big picture: epiplexity offers a way to quantify “how much a realistic learner can really learn” from data. That makes it a promising tool for designing better training data, improving generalization to new tasks, and understanding why today’s large models get so much power from the right kind of data.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of concrete gaps the paper leaves unresolved, organized to help guide future work.

Theory and formal foundations

- Formal chain rules and decomposition laws: establish when (and how tightly) relates to , , and (e.g., subadditivity, superadditivity, data-processing–style inequalities), beyond noting that in general.

- Invariance and robustness: characterize sensitivity of and to (i) choice of universal Turing machine, (ii) encoding schemes, and (iii) small changes to the model class or runtime bound; provide normalization or reference baselines to reduce constant-factor ambiguity.

- Observer-calibration of the time bound T: provide principled procedures to map real training/inference budgets and architectures (e.g., transformers with depth, KV cache, chain-of-thought) to a concrete time-constructible that meaningfully indexes .

- Extending beyond polynomial-time separations: develop epiplexity under finer resource regimes (e.g., quadratic vs cubic time, circuit depth bounds, memory-bounded observers), and relate these to phenomena in contemporary models (attention, recurrence, tool use).

- Tight lower bounds for natural data: construct natural (not diagonal or contrived) distributions with provably high epiplexity growth (ideally beyond ) under plausible assumptions; clarify links to circuit lower bounds or average-case hardness.

- Relationship to existing notions: formalize comparisons/inequalities between epiplexity and sophistication, effective complexity, logical depth, resource-bounded Kolmogorov complexity, PAC-Bayesian/MDL (NML), and information bottleneck measures.

- Conditional epiplexity for deterministic context: systematize how conditioning on a fixed model/checkpoint/script (deterministic strings) should be encoded and how much of that “context” should count toward vs be treated as side information.

- Composition across data sources: derive general conditions for additivity/subadditivity of under mixtures, concatenation, and curriculum schedules (e.g., does exceed when cross-source structure can be shared?).

- Ordering/factorization theory: provide criteria predicting when a data ordering or factorization increases (even with worse training loss), and algorithms to optimize factorization for a target observer.

- Likelihood beyond distribution matching (induction/emergence): give rigorous sufficient conditions under which a bounded observer trained by MLE provably learns programs more complex than the data generator; characterize the gap as a function of , model class, and data properties.

Computation, estimability, and metrics

- Tractable lower bounds: develop computable lower bounds on (not only upper bounds) with provable approximation guarantees and known gaps, to complement prequential/requential upper bounds.

- Identifiability and variance: quantify the sensitivity of estimates to optimizer choice, hyperparameters, randomness (seeds), batch order, and implementation details; provide protocols for confidence intervals and reproducible reporting.

- Program length accounting: specify what counts toward in practice (architecture spec, optimizer, schedule, data pipeline, augmentations, seeds, precision modes), and standardize an accounting scheme to enable fair cross-study comparisons.

- Models without tractable likelihoods: extend measurement to diffusion models, energy-based models, RL/self-play loops, and masked-language pretraining where exact log-likelihood or exact sampling is unavailable; justify approximations (surrogates, annealed importance sampling, pathwise bounds).

- Teacher–student KL estimator: analyze bias/variance and failure modes of cumulative KL estimates (teacher capacity mismatch, temperature, label smoothing, calibration errors); provide diagnostics and corrections.

- Per-sample/per-source attribution: develop methods to decompose dataset-level into per-example or per-source contributions (credit assignment) to enable actionable data filtering and selection.

- Scaling laws: formalize and empirically validate conditions under which scales with dataset size (e.g., power laws), and disentangle scaling of from as data grows and models change.

Applications, data design, and empirical validation

- Causal tests for OOD benefit: design interventions that manipulate while holding confounders fixed (size, domain, tokenization), to establish causal links between higher epiplexity and OOD/task transfer benefits across modalities and tasks.

- Data ordering/curriculum optimization: create algorithms that reorder or factorize data to maximize for a given observer and validate resulting OOD gains; quantify trade-offs between in-distribution loss and structural program acquisition.

- Synthetic data generation policies: formalize compute–epiplexity trade-offs for deterministic data generation (self-play, simulation, program synthesis) and identify when “creating information with computation” is cost-effective for downstream generalization.

- Cross-modality comparisons: systematically compare across text, code, images, audio, video, and multimodal datasets, to explain modality-specific transfer patterns and guide pretraining mix design.

- Mechanistic alignment: connect to interpretable circuit formation (e.g., induction heads, algorithmic modules), and test whether datasets with higher yield more reusable or compositional internal structures.

Assumptions, scope, and robustness

- Cryptographic assumptions: clarify implications if one-way functions or CSPRNGs do not exist (uniform vs non-uniform adversaries), and examine how weaker assumptions (quasi-poly hardness, depth-limited hardness) alter Theorem 1 and subsequent claims.

- Non-IID and heterogeneous corpora: extend the framework to nonstationary, mixture, or temporally dependent data common in large pretraining corpora; define for streams and online settings.

- Noise, duplication, and spurious compressibility: study how label noise, near-duplicates, templated content, and formatting artifacts affect vs , and develop decontamination methods that raise structural content without inflating randomness.

- Privacy and safety: analyze interactions between increasing and risks of memorization, privacy leakage, and harmful structure acquisition; develop privacy-preserving or safety-constrained epiplexity optimization.

- Continuous data and quantization: generalize definitions and estimators from binary strings to continuous/high-precision data, including the role of quantization and discretization in and .

- Standardization and benchmarks: propose reference observers, runtime bounds, and benchmark suites for measuring epiplexity, enabling consistent comparison across datasets, labs, and model classes.

Glossary

- Advice strings: Non-uniform auxiliary information provided to a polynomial-time algorithm, varying with input length. "making use of advice strings $\{a_k\}_{k\in\mathbb{N}$ of length )"

- Algorithmic information theory: A framework studying information content and randomness via computation and description length (e.g., Kolmogorov complexity). "In algorithmic information theory, there is a lesser known concept that captures exactly this idea, known as sophistication"

- Block cipher: A deterministic keyed permutation on fixed-size blocks used in encryption. "the threefish block cypher \citep{salmon2011parallel}"

- Chaitin's incompleteness theorem: A result showing limits on proving high Kolmogorov complexity within formal systems. "The difficulty of finding high sophistication objects is a consequence of Chaitin's incompleteness theorem \citep{chaitin1974information}."

- Cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator (CSPRNG): A PRG whose outputs are indistinguishable from true randomness by any polynomial-time algorithm. "cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (CSPRNG or PRG) are defined as functions which produce sequences which pass all polynomial time tests of randomness."

- Epiplexity: The structural information a computationally bounded observer can extract, defined via time-bounded MDL. "we define a new information measure, epiplexity (epistemic complexity), which formally defines the amount of structural information that a computationally-bounded observer can extract from the data"

- Entropy (Shannon): Expected surprisal of a random variable; measures average uncertainty. "Shannon information assigns to each outcome a self-information (or surprisal) based on the probability , and an entropy for the random variable "

- Entropy (time-bounded): The unpredictable information under a computational time constraint, from the optimal time-bounded model. "We define the -bounded epiplexity and entropy of the random variable as"

- Indistinguishability: Cryptographic notion that two distributions cannot be told apart by any polynomial-time test. "The definition of indistinguishability via polynomial time tests is equivalent to a definition on the failure to predict the next element of a sequence"

- Invariant measure: A probability measure preserved by a dynamical system’s evolution. "the Lorenz attractor invariant measure (\Cref{sec:paradox})"

- Kolmogorov complexity: Length of the shortest program producing a string on a universal Turing machine. "The (prefix) Kolmogorov complexity of a finite binary string is ."

- Kraft's inequality: A condition bounding the number of prefix-free codewords of given lengths. "From Kraft's inequality \citep{Kraft1949Device,McMillan1956TwoInequalities}, there are at most (prefix-free) programs of length "

- Levin complexity: A resource-bounded measure of description length balancing program size and runtime. "Levin complexity~\citep{LiVitanyi2008} or time bounded Kolmogorov complexity~\citep{allender2011pervasive}."

- Martin-Löf randomness: Randomness defined by passing all computable statistical tests. "Martin-L\"of Randomness: No algorithm exists to predict the sequence."

- Minimum Description Length (MDL): Principle choosing models that minimize total code length of model plus data given the model. "Finally, we review the minimum description length principle (MDL), used as a theoretical criterion for model selection"

- Negligible function: A function that decreases faster than the reciprocal of any polynomial. "Here means that the function decays faster than the reciprocal of any polynomial ( for all integers and sufficiently large )."

- Non-uniform probabilistic polynomial time (PPT): Polynomial-time algorithms allowed polynomial-length advice dependent on input size. "for every non-uniform probabilistic polynomial time algorithm "

- Non-uniform one-way function (OWF): Efficiently computable function hard to invert for any non-uniform PPT adversary. "We say is one-way against non-uniform adversaries if for every non-uniform PPT algorithm (i.e., a polynomial-time algorithm with advice strings $\{a_n\}_{n\in\mathbb{N}$ of length )"

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization: Performance on tasks or data distributions different from those seen during training. "In \autoref{sec:ood}, we demonstrate that epiplexity correlates with OOD generalization"

- Prefix-free universal Turing machine: A UTM whose valid programs form a prefix-free set, enabling self-delimiting codes. "Fix a \ universal prefix-free Turing machine ."

- Prequential coding: A coding method that sequentially encodes data using predictions from models trained on past data. "based on prequential coding \citep{dawid1984present}"

- Probabilistic model (time-bounded): A program that supports sampling and probability evaluation within a fixed time budget. "A (prefix-free) program is a -time probabilistic model over "

- Quasipolynomial time: Runtime of the form exp(polylog(n)), between polynomial and exponential. "quasipolynomial time \citep{liu2024direct}"

- Randomness discrepancy: The shortfall of a string’s Kolmogorov complexity from its length (n − K(x)). "Equivalently, randomness discrepancy is defined as "

- Random tape: An infinite sequence of random bits provided as input to randomized algorithms. "where is an infinite random tape"

- Requential coding: A coding approach that encodes training procedures to more efficiently describe model weights. "and requential coding \citep{finzi2026requential}"

- Resource-bounded Kolmogorov complexity: Kolmogorov complexity measured under constraints on computational resources like time. "resource bounded forms of Kolmogorov complexity \citep{allender2011pervasive}"

- Self-delimiting program: A program that encodes its own length so concatenations are decodable without separators. "self-delimiting program (a program which also encodes its length)"

- Self-information (surprisal): The information content of an outcome, equal to −log probability. "self-information (or surprisal) "

- Sophistication (naive): The minimal description length of a set from which a string is a near-random element, quantifying structure. "Sophistication, like Kolmogorov complexity, is defined on individual bitstrings"

- Time-constructible function: A function T(n) for which a machine can count exactly T(n) steps given input size n. "Let be non-decreasing time-constructible function"

- Time-bounded entropy: Expected code length of data under the optimal model that runs within a time bound. "We define the -bounded epiplexity and entropy of the random variable as"

- Time-bounded Kolmogorov complexity: Kolmogorov complexity variant that restricts the runtime of generating programs. "time bounded Kolmogorov complexity~\citep{allender2011pervasive}"

- Time-bounded probabilistic model: Formal class of models enabling sampling and probability evaluation in bounded time. "A (prefix-free) program is a -time probabilistic model over "

- Two-part MDL: A coding scheme that adds model description length to data encoding length under the model. "The two-part MDL is:"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications translate the paper’s core ideas—epiplexity (structural information extractable by computationally bounded observers) and time-bounded entropy—into deployable practices across sectors. Each item includes potential tools/workflows and key assumptions or dependencies.

- Dataset epiplexity profiling for MLOps and model training (software/AI)

- Use case: Quantify “learnable signal” vs “noise” in candidate datasets before training, weight dataset mixtures, and prioritize high-epiplexity sources for pretraining.

- Workflow/tools:

- Implement proxies for epiplexity such as the area under the training loss curve above final loss and cumulative KL divergence between teacher–student models.

- Integrate an “Epiplexity Profiler” into data pipelines and experiment tracking (e.g., MLFlow/Weights & Biases).

- Extend dataset cards with epiplexity summaries per source and per modality.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Epiplexity proxies depend on model class, training regime, and compute budget; results are observer-dependent.

- Requires consistent training hyperparameters and instrumentation to compare datasets fairly.

- Data curation and source weighting for LLMs and foundation models (software/AI)

- Use case: Improve downstream and out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization by favoring sources with high epiplexity (e.g., well-structured code, math, technical writing) and deprioritizing low-structure content (e.g., random configuration fragments).

- Workflow/tools:

- Per-source epiplexity scoring to weight mixing ratios in corpus construction.

- Automatic filtering heuristics tuned to epiplexity estimates (e.g., detecting pseudorandom artifacts, noisy metadata).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- High epiplexity correlates with useful learned circuits but does not guarantee performance on a specific task.

- Requires scalable, domain-aware heuristics to avoid over-filtering niche yet valuable data.

- Curriculum scheduling and sequence ordering optimization (education/software/AI)

- Use case: Optimize data (and content) orderings to increase structural information extraction—e.g., left-to-right token order for text, progressive concept sequencing in curricula.

- Workflow/tools:

- “Order Optimizer” to explore alternative factorizations and sequence orders that improve epiplexity proxies even if training loss worsens.

- Curriculum schedulers that ramp complexity to maximize structural learning.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Benefits depend on architecture and domain (e.g., transformers exploit directional patterns).

- Must balance epiplexity gains with training stability and convergence.

- Synthetic data creation with emergent structure (software/robotics/education)

- Use case: Generate high-epiplexity synthetic corpora (e.g., cellular automata, chaotic systems, controlled self-play) to build reusable circuits without relying on scarce natural data.

- Workflow/tools:

- “Emergent Structure Generator” producing datasets from simulators (Game of Life, Lorenz systems) and self-play environments, tuned to maximize epiplexity.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Emergence yields learnable patterns only within the observer’s compute and model constraints.

- Synthetic domains must be matched to target capabilities (transfer depends on structural overlap).

- OOD readiness scoring for AI auditing and evaluation (software/policy)

- Use case: Use epiplexity metrics to estimate a model’s potential for structure reuse and OOD transfer, complementing task-specific validation.

- Workflow/tools:

- “OOD Readiness Score” derived from epiplexity profiles of pretraining data.

- Audit dashboards highlighting structural content coverage across domains.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Correlational evidence: epiplexity tracks with OOD performance but is not a guarantee.

- Requires transparent reporting of training regimes and compute budgets.

- Compression-aware training monitors (software/AI)

- Use case: Separate signal from noise during training; trigger adaptive data weighting, early stopping on low-structure batches, or targeted data augmentation.

- Workflow/tools:

- “Teacher–Student KL Tracker” monitoring cumulative KL to identify segments with low structural learnability.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Requires robust teacher models and repeatable training runs.

- KL-based estimates are affected by optimization dynamics and regularization.

- Dataset documentation and procurement guidelines (policy/industry)

- Use case: Standardize dataset selection practices by including epiplexity and time-bounded entropy in documentation; set procurement thresholds for foundation model training.

- Workflow/tools:

- Dataset Card extensions with epiplexity sections, measurement protocols, and model/compute context.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Measurement standardization and reference implementations needed to ensure comparability.

- Observer-dependent metrics must be contextualized (architecture, training budget).

- Academic benchmarking and modality comparison (academia)

- Use case: Benchmark datasets by epiplexity across modalities (text, images, code), investigate why text pretraining transfers more broadly, and design benchmarks targeting structural learning.

- Workflow/tools:

- Open epiplexity datasets and leaderboards; shared measurement pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Requires community consensus on proxies (prequential/requential coding) and reproducible protocols.

- Healthcare data selection and cleaning (healthcare)

- Use case: Prioritize EHR segments and imaging cohorts with higher structural regularities (e.g., longitudinal patterns) to boost clinically relevant generalization.

- Workflow/tools:

- Epiplexity screening to guide cohort construction and feature engineering; integrate with privacy-safe pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Domain constraints (privacy, bias) may limit measurement fidelity.

- Requires careful validation to avoid excluding rare but critical signals.

- Market data curation for forecasting (finance)

- Use case: Identify segments with stable structural patterns to train forecasting models; deprioritize pseudorandom or high-noise windows.

- Workflow/tools:

- “Structural Information Meter” for market regimes; adaptive sampling of data windows.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Financial time series are non-stationary; structure varies by regime.

- Over-filtering can remove useful volatility signals.

- Personalized learning and content authoring (daily life/education)

- Use case: Sequence study materials to maximize structural learning; prioritize resources with coherent dependencies and long-range structure.

- Workflow/tools:

- “Study Planner” integrating epiplexity-inspired sequencing (progressive concept build-up, directional presentation).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Practical proxies (e.g., expert heuristics) may substitute for direct epiplexity measurement on small-scale content.

- Individual differences in learners may require adaptation.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, and standardization (including better measurement protocols such as requential coding and broader empirical validation).

- Epiplexity-based data markets and valuation (finance/industry/policy)

- Vision: Price datasets based on measured structural content under specified observer constraints; establish registries for dataset epiplexity ratings.

- Potential products/workflows:

- “Data Valuation Exchange” with standardized measurement, audits, and SLAs.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Requires consensus standards, third-party verification, and legal frameworks.

- Regulatory frameworks and OOD certification (policy)

- Vision: Use epiplexity as part of certification for foundation models’ OOD preparedness, dataset quality audits, and safety cases (e.g., autonomy, medical AI).

- Potential products/workflows:

- Certification protocols combining epiplexity profiles with domain-specific validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Measurement reliability, transparency requirements, and domain expert oversight.

- Epiplexity-aware architecture and optimization design (software/AI)

- Vision: Architectures and training strategies explicitly tuned to extract and reuse structural circuits (e.g., modular networks, induction heads).

- Potential products/workflows:

- “Circuit Library” tooling that catalogs reusable subprograms learned from high-epiplexity data.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Mechanistic interpretability advances; efficient methods to detect, isolate, and reuse circuits.

- Closed-loop synthetic data generation to increase epiplexity (software/robotics)

- Vision: Adaptive generators and simulators that iteratively produce data maximizing structural learning under compute constraints.

- Potential products/workflows:

- Auto-simulation frameworks (self-play, curriculum generation) paired with epiplexity feedback.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable feedback signals; transferability of emergent structures to target tasks.

- Education technology and curriculum authoring optimized by epiplexity (education)

- Vision: Authoring tools that analyze structural dependencies in content and recommend optimal sequencing to maximize long-term transfer.

- Potential products/workflows:

- “Epiplexity-Aware Course Builder” for instructors and platforms.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Evidence linking epiplexity proxies to human learning outcomes; alignment with pedagogical standards.

- Standardized measurement protocols and benchmarks (academia/industry)

- Vision: Mature implementations of prequential/requential coding, teacher–student KL instrumentation, and cross-modality benchmarks.

- Potential products/workflows:

- Reference pipelines and open datasets for epiplexity/time-bounded entropy.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Shared compute profiles, agreed-on observer definitions, and reproducibility.

- Cryptography-aware ML data hygiene (software/security)

- Vision: Systematic detection and exclusion of pseudorandom artifacts from training corpora (high time-bounded entropy, negligible epiplexity), improving structural learning efficiency.

- Potential products/workflows:

- “PRNG Artifact Scanner” integrated into ingestion pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Practical detectors for cryptographic artifacts; domain tuning to avoid false positives.

- Dynamic data-in-the-loop curation for production systems (industry/AI)

- Vision: Continuous measurement of incoming data streams’ epiplexity, automatic retraining triggers, and adaptive weighting for sustained performance.

- Potential products/workflows:

- “Epiplexity Orchestrator” in MLOps platforms that manages data lifecycles.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robust online proxies; safeguards against feedback loops and dataset drift.

- Safety-critical dataset interventions via ordering and structure (healthcare/autonomous systems)

- Vision: Reordering and structuring training data to enhance generalization in safety-critical domains (e.g., medical imaging sequences, sensor fusion timelines).

- Potential products/workflows:

- Protocols for sequence curation and structural augmentation under regulatory oversight.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Rigorous clinical validation; handling of rare events without reducing sensitivity.

- Energy-efficient AI via high-epiplexity data selection (energy/industry)

- Vision: Reduce training compute and carbon footprint by prioritizing structurally rich data that accelerates learning.

- Potential products/workflows:

- “Green Training Planner” that optimizes dataset composition for learning efficiency.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable mapping from epiplexity proxies to convergence speed; lifecycle analysis.

- Robotic learning curricula (robotics)

- Vision: Sim-to-real transfer improved by training on structured simulations that build reusable control/perception circuits.

- Potential products/workflows:

- Curriculum generators aligned to epiplexity feedback and real-world validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Transferability of simulated structures; robust domain randomization strategies.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Observer dependence: Epiplexity and time-bounded entropy are defined relative to computational constraints and model classes; comparisons must specify the observer (architecture, training budget).

- Measurement tooling: Prequential and requential coding, teacher–student KL, and loss-curve AUC proxies need standardization, reference implementations, and benchmarking.

- Task relevance: Epiplexity quantifies structural information learned, not its task-specific utility; downstream validation remains essential.

- Theoretical underpinnings: Some results rely on cryptographic assumptions (e.g., existence of one-way functions); practical detectors and proxies must be validated empirically.

- Data governance: Policies and audits should contextualize epiplexity with privacy, fairness, and domain constraints to avoid harmful filtering or biased dataset selection.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.