Universal Reasoning Model (2512.14693v3)

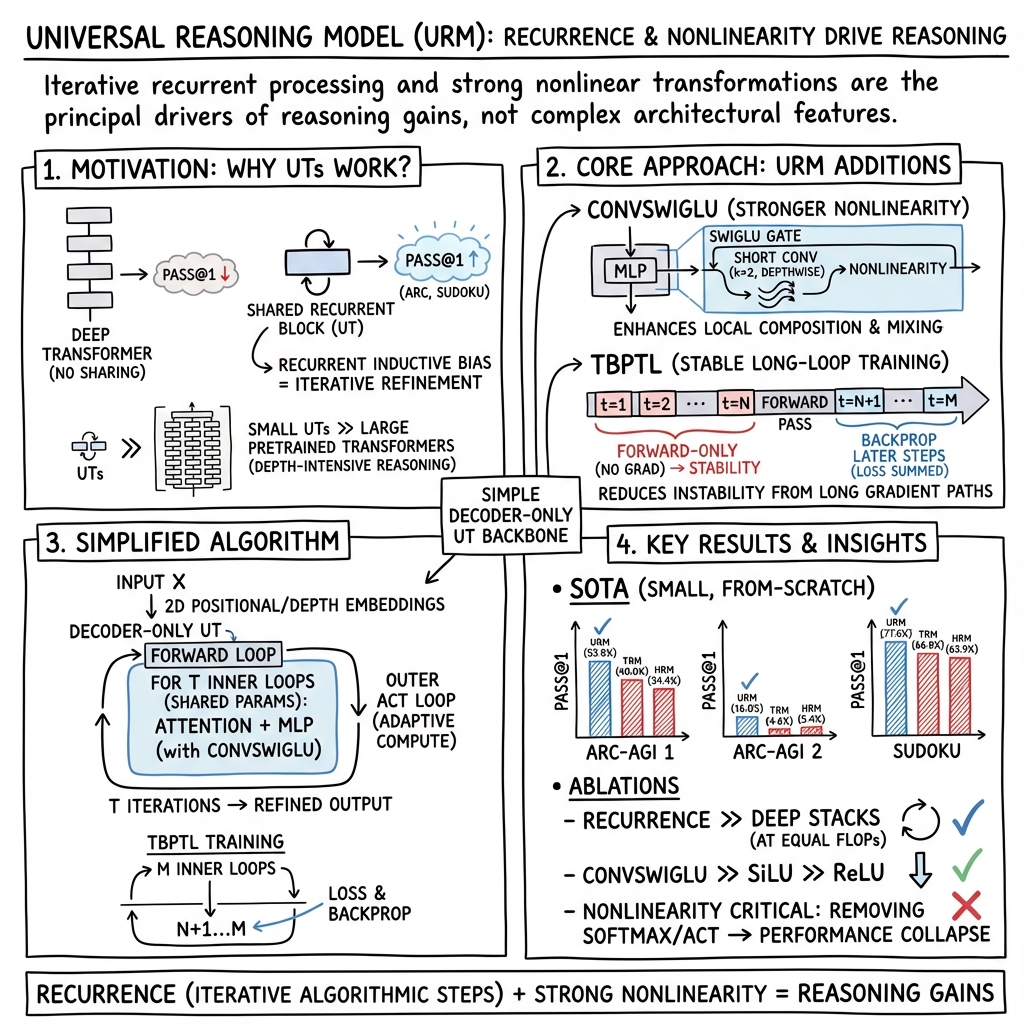

Abstract: Universal transformers (UTs) have been widely used for complex reasoning tasks such as ARC-AGI and Sudoku, yet the specific sources of their performance gains remain underexplored. In this work, we systematically analyze UTs variants and show that improvements on ARC-AGI primarily arise from the recurrent inductive bias and strong nonlinear components of Transformer, rather than from elaborate architectural designs. Motivated by this finding, we propose the Universal Reasoning Model (URM), which enhances the UT with short convolution and truncated backpropagation. Our approach substantially improves reasoning performance, achieving state-of-the-art 53.8% pass@1 on ARC-AGI 1 and 16.0% pass@1 on ARC-AGI 2. Our code is avaliable at https://github.com/UbiquantAI/URM.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper studies how to build small AI models that can reason through tricky puzzles step by step. The authors focus on a type of model called a Universal Transformer (UT), which “thinks” by repeating the same layer many times, like working through a puzzle with several passes. They discover what makes UTs good at reasoning and then design a new model, the Universal Reasoning Model (URM), that improves on UTs and sets new records on the ARC-AGI puzzle benchmarks and Sudoku.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The researchers wanted to answer two main questions in simple terms:

- Which parts of Universal Transformers actually make them good at reasoning?

- Can we make a small, efficient model that reasons even better without complicated design tricks?

How did they approach the problem?

They analyzed different versions of Universal Transformers and ran many experiments to see what matters most. Based on what they learned, they built URM with two key upgrades. Here’s the approach in everyday language:

Universal Transformer: thinking in loops

A standard Transformer stacks many different layers. A Universal Transformer instead uses the same layer over and over—like editing an essay many times with the same tool. Each loop refines the model’s understanding, step by step. This “recurrent” setup helps with problems that need multiple stages of thinking, such as ARC-AGI puzzles, where the rules change from task to task.

ConvSwiGLU: adding small local “nudges”

Inside Transformer layers, there’s a part called the MLP (a tiny neural network) that applies “activation functions,” which are like smart switches that shape how the model learns patterns. The authors add a short, lightweight convolution (think: a small window that looks at neighboring tokens) after a gated activation called SwiGLU. This module, called ConvSwiGLU, lets the model mix nearby information in a simple, fast way—like glancing at the puzzle pieces next to each other—boosting the model’s ability to represent complex patterns.

Truncated Backpropagation Through Loops (TBPTL): focus feedback on recent steps

When training a model that thinks in many loops, sending training signals (gradients) all the way back through every loop can get noisy and unstable—like trying to remember and fix every single move you made in a long game. TBPTL solves this by only sending feedback through the last few loops, where the model’s final decisions happen. This makes training more stable and still teaches the model to reason across several steps.

Adaptive Computation Time (ACT): think more when needed

ACT lets the model decide how many thinking steps to use for each part of the input. Easy tokens can stop early; hard ones can use more loops. It’s like spending more time on the tricky parts of a test and less on the easy ones.

What did they find?

The authors ran ablation studies (tests where they remove or change parts) and head-to-head comparisons. Here are the key findings:

- The main reason Universal Transformers are good at reasoning is their “recurrent inductive bias,” meaning repeating the same layer to refine thinking matters more than stacking many different layers.

- Strong nonlinearity (powerful activation functions, like SwiGLU and attention’s softmax) is crucial. Weakening these switches hurts performance a lot.

- The new URM model, with ConvSwiGLU and TBPTL, beats earlier UT-based models:

- ARC-AGI 1: 53.8% pass@1 (best single small model trained from scratch under comparable settings)

- ARC-AGI 2: 16.0% pass@1

- Sudoku: 77.6% accuracy

- Short convolution works best when added after the MLP expansion (not inside attention), showing that most of the expressive power comes from the nonlinear MLP part.

- Universal Transformers are more parameter-efficient than regular Transformers for reasoning: using loops with shared weights gives better results than simply making models deeper or wider.

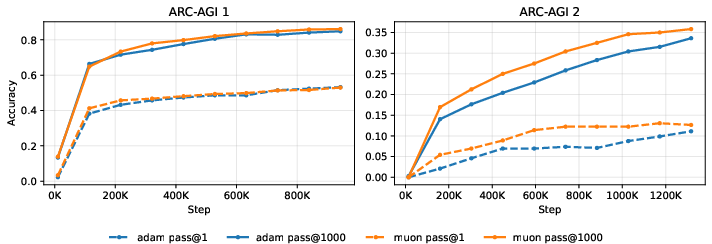

- A different optimizer (Muon) trains faster early on but ends up with a similar final accuracy, suggesting the architecture itself is the main driver of strong reasoning.

Why does it matter?

This research shows you don’t need huge, complicated models to reason well. Instead:

- Let the model think in multiple steps (loops) using the same tool repeatedly.

- Keep strong nonlinear components (smart switches) to capture complex patterns.

- Add small local context (short convolution) where it helps most.

- Train stably by focusing feedback on the most recent reasoning steps (TBPTL).

Practically, this means we can build smaller, more efficient AI systems that solve multi-step problems—like puzzles, algorithms, and logic tasks—better than many LLMs trained on massive data. It points the way toward future reasoning-focused AI: simpler designs, smart recurrence, and carefully placed nonlinear components.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of missing pieces, uncertainties, and open questions that future researchers could act on:

- External validity: URM is only evaluated on ARC-AGI 1/2 and Sudoku; it is unclear how well it transfers to other reasoning domains (e.g., algorithmic tasks, code reasoning, symbolic math, natural language reasoning, theorem proving).

- Scaling behavior: The paper uses a small model (4 layers, 512 hidden). How do performance, stability, and sample efficiency scale with model size, number of loops, and depth? Are there scaling laws for UT-style recurrence vs standard Transformers?

- Inference-time depth adaptation: Does increasing inner/outer loops at inference improve accuracy beyond training-time loop counts? What are compute–accuracy trade-offs and diminishing returns curves?

- ACT sensitivity: The outer-loop ACT settings (thresholds, penalties, max steps) and their effect on performance, halting distributions, and per-example compute allocation are not analyzed; robustness to ACT hyperparameters is unknown.

- Interaction between ACT and TBPTL: Truncated backprop through inner loops may bias learning of ACT halting in the outer loop; the effect on halting policies and credit assignment remains unexplored.

- TBPTL design: The choice to truncate gradients for the first two inner loops is empirical; there is no analysis of adaptive or learned truncation horizons, per-example truncation, or sensitivity to total loop count (M) and truncation index (N).

- Gradient dynamics: No direct measurements of gradient norms, signal-to-noise, or alignment across loops are reported; it is unknown how TBPTL affects vanishing/exploding gradients and optimization stability across longer rollouts.

- Compute and memory accounting: The paper does not quantify wall-clock, FLOPs, and memory trade-offs for UT recurrence, ACT, and TBPTL (e.g., memory savings from truncation vs extra forward-only loops; FLOPs/token under dynamic halting).

- Fairness of FLOPs comparisons: UT vs vanilla Transformer comparisons report coarse FLOPs multiples but do not account for recurrent reuse, ACT variability, and implementation details; a precise, token-level compute audit is missing.

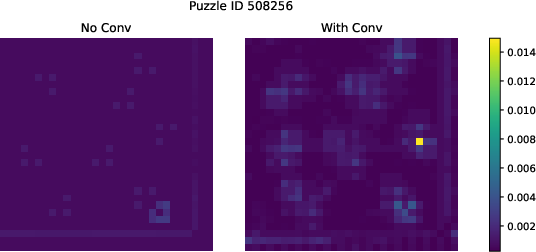

- ConvSwiGLU design space: Only a depthwise 1D conv with kernel size k=2 placed after MLP expansion is studied; broader variants (kernel sizes, dilation, stride, 2D separable convs, causal vs non-causal, pointwise+depthwise combos, pre/post-gating placements) remain unexplored.

- Sequence vs spatial adjacency: For 2D grid tasks (ARC, Sudoku), the short 1D conv operates along the sequence linearization; alignment with true 2D spatial neighborhoods is unclear. Would 2D convolutions or alternative token orderings yield larger gains?

- Tokenization/puzzle embedding: The paper references a “puzzle embedding” but does not detail tokenization choices, 2D positional encodings, or how these interact with short convolutions; ablations on tokenization/positional encodings are missing.

- Nonlinearity choices: While SwiGLU outperforms SiLU/ReLU, the search over activation/gating families (e.g., GEGLU, ReGLU, Gated Attention Units, Mixture-of-SwiGLU, normalization-aware activations) is limited; activation width ratios are not explored.

- Attention kernels: Removing softmax collapses performance, but alternatives (e.g., entmax/sparsemax, temperature tuning, kernelized/linear attention, softmax with learned temperature) are not explored; their interaction with recurrence is unknown.

- Interpretability of loops: There is no mechanistic analysis of what each recurrent step computes (e.g., algorithmic sub-steps, abstraction stages). Loop-level ablations, probes, and intervention studies could reveal the computation schedule learned by UT recurrence.

- Error analysis: The paper does not categorize ARC/Sudoku failure modes; which puzzle types drive errors, and do failures correlate with halting depth, loop count, or specific architectural choices?

- Robustness and OOD generalization: Sensitivity to distribution shifts (e.g., color remapping, grid sizes, clutter, adversarial perturbations) and transfer across ARC-style tasks remains unknown.

- Variance and reproducibility: No confidence intervals or multi-seed variance are reported; sensitivity to random seed, optimizer hyperparameters, and data augmentation strength is unquantified.

- Data augmentation details: Augmentation recipes are inherited from prior work, but their precise composition, ablations, and impact on generalization and potential leakage are not reported.

- Optimizer comparison scope: Muon accelerates convergence but does not improve asymptotics; it remains open whether second-order or curvature-aware methods can improve final generalization, and how optimizer choices interact with TBPTL/ACT.

- Benchmarking against stronger baselines: Comparisons exclude ensembles, test-time scaling, vision pipelines (VARC), and strong LLM tool-use/CoT baselines; how URM fares under matched compute/budget settings is unresolved.

- Compute–accuracy frontier at sampling time: Gains widen with pass@1000, but sampling hyperparameters (temperature, top-k/p) and diversity metrics are not reported; decoding strategies and their compute costs need systematic study.

- Theoretical grounding: The claim that “recurrent inductive bias + strong nonlinearity” is the main driver lacks formal analysis; can we characterize expressivity, sample complexity, or provable advantages of UT+ConvSwiGLU and TBPTL?

- Partial parameter sharing: Only full sharing across depth is used; the benefits of partial sharing (e.g., shared cores with per-loop adapters/LoRA/FiLM) and their effect on stability and capacity are unexplored.

- Longer-horizon recurrence: Behavior with more than 8 inner loops or more than 16 ACT steps is not studied; do benefits continue, plateau, or regress, and how does TBPTL need to adapt?

- Halting diagnostics: The paper does not report halting distributions, correlation with task difficulty, or per-example compute budgeting; it is unknown whether ACT meaningfully targets hard instances.

- Sudoku scope: Performance is reported for standard Sudoku only; generalization to larger boards (e.g., 16×16) and variants (Killer, X-Sudoku) is untested.

- Implementation specifics: Minor inconsistencies (e.g., LayerNorm vs RMSNorm in different sections), missing hyperparameters (e.g., MLP expansion ratio m), and equation typos impede exact reproduction and invite clarification.

Glossary

- 2-D sinusoidal embeddings: Positional encodings that add periodic signals across both position and refinement depth dimensions to inform recurrence steps. "UT adds 2-D sinusoidal embeddings at each step."

- Adaptive Computation Time (ACT): A mechanism allowing different tokens to take a variable number of recurrent steps by predicting when to halt. "With ACT \cite{act}, different tokens may halt at different recurrent steps."

- AdamAtan2 optimizer: An adaptive optimizer variant used for training, referenced as a baseline in the paper’s experiments. "All models are trained with the AdamAtan2 optimizer~\cite{adamatan2}."

- ARC-AGI: A benchmark suite for abstract reasoning tasks (versions 1 and 2) used to evaluate model reasoning capabilities. "ARC-AGI 1 and 2 scores are taken from the official ARC-AGI leaderboard for reliability."

- Channel mixing: The interaction and combination of feature channels to enhance representation expressiveness. "significantly enhances channel mixing."

- ConvSwiGLU: A feed-forward block that augments SwiGLU with a depthwise short convolution to inject local token interactions. "we introduce a ConvSwiGLU (motivation see Section~\ref{nonlinear})"

- Cross-entropy loss: A standard loss function for classification and language modeling tasks. "where is cross-entropy loss function."

- Decoder-only design: An architecture using only transformer decoder blocks (no encoder) for autoregressive modeling. "with the difference being its decoder-only design."

- Depth adaptation: Adjusting the number of recurrent refinement steps at inference for efficiency or performance. "enabling (i) depth adaptation at inference"

- Depthwise convolution: A convolution that operates separately on each channel, here used as a short 1D token-local operation. "we apply a depthwise 1D convolution over the gated features:"

- Effective depth: The realizable computational depth achieved by iterative/refinement steps rather than stacking many distinct layers. "recurrent computation converts the same budget into increased effective depth"

- EMA (Exponential Moving Average): A parameter averaging technique to stabilize training and improve generalization. "apply an exponential moving average (EMA) to model parameters"

- Ensembling: Combining multiple models or runs to boost evaluation performance. "excluding test-time scaling, ensembling, and visual methods such as VARC"

- FLOPs: A compute budget measure counting floating-point operations used to compare model cost. "At 32Ã FLOPs, reallocating computation from deep, non-shared layers to recurrent refinement improves pass@1..."

- Gating mechanisms: Nonlinear components (e.g., in GLU variants) that control information flow via multiplicative gates. "the function and impact of gating mechanisms remain insufficiently explored"

- Halting probability: In ACT, the per-token probability predicted at each step to decide when to stop computation. "each position predicts a halting probability"

- Inner loop: The model’s recurrent refinement cycle applied multiple times per layer or timestep. "The inner loop runs for 8 steps, with the first two steps being forward-only"

- Layer normalization (LayerNorm): A normalization technique applied within transformer blocks to stabilize training. "layer normalization:"

- MHSA (Multi-Head Self-Attention): The attention mechanism that allows tokens to attend to all others across multiple heads. "Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA)"

- Muon optimizer: An optimizer (Momentum Updated Orthogonal Newton) that applies orthogonal, curvature-aware updates. "Muon (Momentum Updated Orthogonal Newton) optimizer"

- Parameter efficiency: Achieving strong performance with fewer parameters via recurrent reuse and shared weights. "preserving parameter efficiency."

- Pass@n: A sampling-based evaluation metric reporting whether at least one of n outputs is correct. "pass@n denotes the pass rate when sampling n answers from the model;"

- Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN): The per-token MLP sublayer in Transformer blocks. "Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN)"

- Puzzle embedding: Task-specific embeddings for puzzle inputs (e.g., ARC grids) with separate optimization settings. "the puzzle embedding uses a learning rate of "

- Recurrent inductive bias: Architectural bias favoring iterative computation over depth to better model multi-step reasoning. "recurrent inductive bias intrinsic to the Universal Transformer."

- RMSNorm: A normalization variant using root-mean-square statistics, sometimes preferred over LayerNorm. "such as the RMSNorm applied after each layer"

- SDPA (Scaled Dot-Product Attention): The core attention computation using scaled query-key dot products. "after the SDPA output"

- Separable convolution: A factorized convolution (depthwise followed by pointwise) used as an alternative transition in UTs. "either a feed-forward network or separable convolution."

- SiLU: A smooth activation function (Sigmoid-Weighted Linear Unit) used within GLU-style blocks. "SwiGLU SiLU"

- SwiGLU: A gated MLP activation (SiLU gate times linear path) improving expressiveness over ReLU/GeLU variants. "Unlike the conventional point-wise SwiGLU \cite{glu}"

- TBPTL (Truncated Backpropagation Through Loops): Limiting gradient flow to recent recurrent iterations to stabilize optimization. "Truncated Backpropagation Through Loops (TBPTL)"

- TBPTT (Truncated Backpropagation Through Time): The RNN training technique of truncating gradients across timesteps, referenced as analogous to TBPTL. "truncated backpropagation through time (TBPTT)"

- Test-time scaling: Increasing inference-time compute (e.g., more samples or steps) to boost performance without retraining. "excluding test-time scaling, ensembling, and visual methods such as VARC"

- Theoretical expressivity: The formal representational capacity of a model class to realize complex functions. "higher theoretical expressivity than fixed-depth Transformers."

- Unembedding function: The projection from hidden states back to vocabulary logits (language modeling head). "the unembedding function (or language modeling head)"

- Universal Reasoning Model (URM): The proposed UT-based model with ConvSwiGLU and truncated loop backpropagation for reasoning tasks. "we propose the Universal Reasoning Model (URM)"

- Universal Transformer (UT): A transformer variant that reuses a single transition block recurrently across depth. "Universal transformers (UTs) have been widely used"

- Vocabulary logit space: The pre-softmax output space over tokens produced by the language modeling head. "vocabulary logit space"

- Weight decay: L2-regularization-like parameter penalty used during optimization. "Weight decay is set to 0.1"

- Weight tying: Reusing the same parameters across recurrent depth steps to enforce sharing and improve efficiency. "A key design of UT is weight tying across depth."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a concise set of deployable, real-world uses that leverage the paper’s findings and the Universal Reasoning Model (URM) architecture as-is, or with light engineering effort.

- Software and AI Engineering

- Iterative reasoning microservice for discrete tasks

- Sector: software

- What: A small, UT-based backend service that performs iterative refinement on tasks like rule-based data transformations (e.g., ARC-like pattern matching), Sudoku solving, or stepwise configuration generation.

- Tools/Workflow: Wrap URM behind an API; enable Adaptive Computation Time (ACT) for per-input compute control; integrate pass@k sampling to increase robustness.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Tasks should exhibit clear iterative structure; reliability measured via pass@k; domain-specific input encoders may be needed.

- Training stability toolkit for looped/recursive transformers

- Sector: software/ML tooling

- What: Adopt Truncated Backpropagation Through Loops (TBPTL) and Muon optimizer to accelerate and stabilize training of existing recurrent or looped transformer variants.

- Tools/Workflow: Add TBPTL scheduling (e.g., N forward-only inner loops, gradients on last M−N loops); switch to Muon for faster convergence; monitor gradient norms.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Benefits are strongest in deep recurrent regimes; requires tuning of truncation horizon (N).

- Architecture patch: ConvSwiGLU for stronger nonlinearity

- Sector: software/ML tooling

- What: Drop-in modification to MLP blocks by inserting short depthwise convolution after expansion, thereby improving nonlinear channel mixing and iterative reasoning without heavy cost.

- Tools/Workflow: Update MLP to

SwiGLU + depthwise 1D conv (k≈2) + SiLU; avoid inserting conv inside attention projections. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Gains are most reliable in reasoning tasks; placement matters (post-MLP expansion yields best effect).

- Resource-efficient edge reasoning

- Sector: embedded/IoT

- What: On-device small UT-based models for constrained environments to perform multi-step decisions (e.g., rule-based anomaly flags, local pattern corrections).

- Tools/Workflow: ACT to bound per-input compute; parameter sharing across depth to limit memory footprint.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Input size modest; latency tolerates several inner loops; domain inputs encoded compactly.

- Education and Daily Life

- Puzzle and logic tutors that show iterative steps

- Sector: education/consumer apps

- What: Apps that teach users how to solve logic puzzles or math transformations via explicit iterative steps generated by UT-style refinement.

- Tools/Workflow: Use pass@k for multiple solution paths; visualize inner-loop states to teach “how” not just “what.”

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Content resembles ARC/Sudoku-style discrete transformations; requires curricular UX for step explanations.

- Spreadsheet/data cleaning assistant for pattern transformation

- Sector: productivity software

- What: A plugin that proposes stepwise transformations (e.g., column remapping, cell-rule application) learned from examples, similar to ARC task structure.

- Tools/Workflow: Present an iterative “plan and apply” flow; allow ACT-based early stopping when changes stabilize.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Requires labeled examples or consistent transformation rules; safe sandboxing for changes.

- Research and Benchmarking

- Reasoning benchmark augmentation and reproducible baselines

- Sector: academia

- What: Use provided URM code as a strong, reproducible baseline on ARC-AGI-style datasets; evaluate nonlinearity ablations and loop truncation settings.

- Tools/Workflow: Standardize the placement of short conv, ACT hyperparameters, and TBPTL windows; report pass@k metrics consistently.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Comparable data regimes to HRM/TRM; fidelity to official evaluation scripts.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, domain adaptation, or validation to safely and effectively deploy in complex, high-stakes settings.

- Healthcare

- Stepwise clinical reasoning assistants (differential diagnosis, protocol planning)

- Sector: healthcare

- What: UT-based modules that iteratively refine hypotheses, propose diagnostic pathways, and adjust based on new evidence.

- Tools/Workflow: Multi-modal inputs (EHR, imaging, labs) with reasoning loops; ACT to allocate compute to complex patients; ConvSwiGLU-enhanced MLP for nonlinear clinical patterns.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Domain-specific training data; rigorous evaluation for safety; regulatory approvals; explainability mechanisms for human oversight.

- Finance

- Iterative scenario generation for risk and trading strategies

- Sector: finance

- What: Small recurrent models that explore market microstructure patterns and generate multi-step strategy refinements.

- Tools/Workflow: Train URM on proprietary market event sequences; TBPTL to stabilize deep loops; pass@k sampling for robust candidate strategies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-quality, time-synchronized data; backtesting infrastructure; controls for overfitting and regime shifts; compliance reviews.

- Robotics and Planning

- Multi-step task planning and correction loops

- Sector: robotics

- What: UT-style recurrent planners that iteratively refine action sequences for assembly, navigation, or manipulation, correcting errors over loops.

- Tools/Workflow: Integrate perception inputs; ACT for adaptive planning depth; visualize inner-loop plans for debugging.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Real-world dynamics modeling; safe recovery behaviors; large-scale embodied datasets; hardware latency constraints.

- Energy and Infrastructure

- Grid operation and scheduling under constraints

- Sector: energy

- What: Iterative optimization modules to adjust load-balancing and maintenance schedules, refining plans as constraints evolve.

- Tools/Workflow: Coupled with optimization solvers; URM to propose candidate adjustments; pass@k to explore diverse feasible plans.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate constraint models; integration with SCADA/EMS; human-in-the-loop validation; robustness to rare events.

- Software Verification and Program Synthesis

- Stepwise code repair and formal verification routines

- Sector: software

- What: Models that iteratively propose patches, run tests, and refine until convergence; or produce proofs with recurrent refinement of lemmas.

- Tools/Workflow: Connect URM to static analysis tools; ACT to scale effort to hard bugs; use Muon/TBPTL for training stability on long reasoning chains.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Labeled bug-fix corpora; integration with CI/CD; formal method tooling for verification; careful hallucination control.

- Education and Assessment

- Adaptive tutoring that modulates compute per student/problem

- Sector: education

- What: ACT-driven tutors that allocate more reasoning to harder problems, showing iterative solution traces tailored to learners.

- Tools/Workflow: Align inner-loop steps with pedagogical scaffolds; track pass@k to gauge progress; personalize truncation windows.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Privacy-preserving data; alignment with curricula; efficacy trials; guardrails to avoid misleading reasoning.

- Policy and Governance

- Procurement and evaluation standards for “reasoning architectures”

- Sector: policy

- What: Frameworks that recognize recurrent inductive bias and iterative compute (ACT) as key capabilities; define metrics beyond accuracy (e.g., pass@k, compute per token).

- Tools/Workflow: Benchmarks that stress multi-step abstraction; audits of adaptive compute allocation; reporting standards for loop truncation and safety.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consensus among regulators and industry; clarity on fairness and resource allocation implications of ACT.

- Hardware and Systems

- Accelerators and runtimes optimized for looped transformers

- Sector: semiconductors/systems

- What: Hardware scheduling and memory models that favor repeated application of shared blocks, fast inner-loop state updates, and ACT-driven early exit.

- Tools/Workflow: Compiler support for parameter sharing; kernels for depthwise short conv; runtime APIs for dynamic halting per token.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Demand from industry workloads; co-design with software stacks; proof of end-to-end efficiency gains on real applications.

- Multimodal Reasoning

- Vision-language looped reasoning for real-world transformations

- Sector: cross-domain (vision, NLP)

- What: Combine URM with visual encoders (e.g., VARC-style) to handle image-to-image or image-to-sequence transformations with iterative refinement.

- Tools/Workflow: Train on paired visual reasoning tasks; apply short conv in language MLP while using strong visual backbones; ACT for token- or region-level halting.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Large, curated multimodal datasets; robust alignment of modalities; reliability under distribution shift.

Cross-cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- Task fit: The strongest gains arise for problems that benefit from iterative refinement and nonlinearity; tasks lacking multi-step structure may see limited benefit.

- Data and evaluation: Domain transfer from ARC-AGI/Sudoku to real-world settings requires high-quality, domain-specific data and appropriate evaluation metrics (e.g., pass@k, sample diversity, convergence diagnostics).

- Safety and oversight: For any safety-critical sector (healthcare, energy, finance, robotics), human-in-the-loop oversight, formal testing, and regulatory compliance are essential.

- Engineering choices: Performance depends on careful placement of short conv (post-MLP expansion), ACT thresholds, and TBPTL truncation windows; misconfiguration can degrade outcomes.

- Integration constraints: Real deployments may require latency budgets, memory limits, and interpretability features (e.g., exposing inner-loop states) to build user trust.

- Scalability: While UTs are parameter efficient, large-scale, multimodal, or long-horizon tasks will need significant engineering and compute, even with ACT and TBPTL optimizations.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.