Native and Compact Structured Latents for 3D Generation (2512.14692v1)

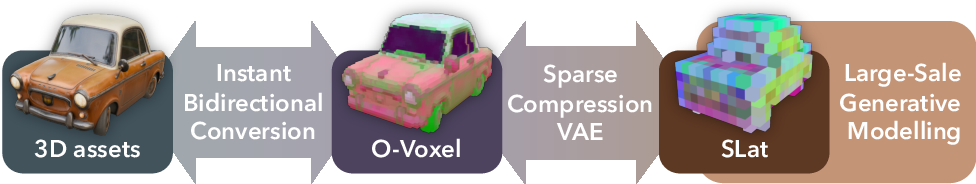

Abstract: Recent advancements in 3D generative modeling have significantly improved the generation realism, yet the field is still hampered by existing representations, which struggle to capture assets with complex topologies and detailed appearance. This paper present an approach for learning a structured latent representation from native 3D data to address this challenge. At its core is a new sparse voxel structure called O-Voxel, an omni-voxel representation that encodes both geometry and appearance. O-Voxel can robustly model arbitrary topology, including open, non-manifold, and fully-enclosed surfaces, while capturing comprehensive surface attributes beyond texture color, such as physically-based rendering parameters. Based on O-Voxel, we design a Sparse Compression VAE which provides a high spatial compression rate and a compact latent space. We train large-scale flow-matching models comprising 4B parameters for 3D generation using diverse public 3D asset datasets. Despite their scale, inference remains highly efficient. Meanwhile, the geometry and material quality of our generated assets far exceed those of existing models. We believe our approach offers a significant advancement in 3D generative modeling.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about making computer-generated 3D objects (like those used in games and movies) faster to create and more realistic, especially for tricky shapes. The authors introduce a new way to store and generate 3D models called O-Voxel. It packs both the shape and the material (how it looks under light) into a compact, easy-to-use format. Using this, they build a system that can turn an input image into a high-quality, fully textured 3D model quickly.

Goals and Questions

The paper focuses on solving three practical problems in 3D generation:

- How can we represent complicated 3D shapes (with holes, thin parts, open edges, and hidden internal pieces) without losing detail?

- How can we include realistic materials (like metal, plastic, glass) together with the shape, so lighting behaves correctly?

- How can we compress this information into a small “code” (called a latent space) so models can generate high-resolution 3D results quickly and efficiently?

How the Method Works (in everyday terms)

To understand the method, think of 3D as a big cube filled with tiny boxes called voxels—like 3D pixels or LEGO blocks. Each voxel can store information.

1) O-Voxel: Smart 3D Boxes

- O-Voxels are special, sparse voxels that only store information where the shape exists (no wasting space in empty areas).

- Each active voxel stores:

- Shape info: a point that helps define the local surface, plus signals about which neighboring boxes connect.

- Material info: the color, how shiny it is, how rough it is, and how transparent it is—these are standard physically based rendering (PBR) parameters used to make objects look realistic in different lighting.

- “Arbitrary topology” means O-Voxel can handle any kind of shape: open sheets, thin wires, overlapping parts, and even sealed cavities inside objects.

- Conversions are instant:

- Mesh to O-Voxel: takes seconds, no complex optimization or rendering needed.

- O-Voxel back to mesh: takes milliseconds, ready to render.

Analogy: O-Voxel is like a compact blueprint where every box that matters knows both the structure of the object and how it should look under light.

2) Sparse Compression VAE: A Powerful Compressor

- A VAE (Variational Autoencoder) is like a super-zipper for data: it compresses the detailed O-Voxel info into a small “code” (latent tokens) and can reconstruct it back with minimal loss.

- Their Sparse Compression VAE is designed specifically for 3D voxels and achieves high compression:

- Up to 16× spatial downsampling (very compact), yet still reconstructs fine details.

- Example: a fully textured object at 1024³ resolution can be encoded into about 9,600 tokens with barely noticeable quality loss.

- Special design tricks make this possible:

- Residual autoencoding layers: smart shortcuts that move information between space and channels to keep details under strong compression.

- Early-pruning upsampler: skips unnecessary parts to save time and memory.

- Optimized residual blocks: use fewer heavy convolutions and more point-wise transformations to keep it fast and accurate.

Analogy: Think of packing a huge LEGO model into a small set of instructions. Their compressor writes instructions so compactly that you can rebuild the model quickly without losing the small decorative pieces.

3) Large Generative Models: From Image to 3D

- After learning the compact latent space, they train large generative models (~4 billion parameters in total) to create 3D assets from images.

- The pipeline has three stages: 1) Predict where the active voxels should be (the sparse structure layout). 2) Generate the shape details in those voxels. 3) Generate the material details (color, metalness, roughness, opacity) aligned to the shape.

- Despite being big, the models are fast:

- About 3 seconds for 512³ resolution,

- ~17 seconds for 1024³,

- ~60 seconds for 1536³ (on a modern GPU).

- Training uses large public 3D datasets and image features from strong vision models to match generation to input pictures.

Analogy: It’s like building a house in three steps—first, mark where rooms go; second, build walls and floors; third, paint and decorate—except they do it in 3D with realistic materials and lighting.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

The authors show that their method:

- Handles complicated shapes better than previous approaches: open surfaces, thin parts, overlapping geometry, and internal structures are captured accurately.

- Generates realistic materials, not just shapes: makes glass look transparent, metal look shiny, and textures look sharp and consistent across views.

- Is very compact and fast: fewer “tokens” (instructions) are needed, so models can scale to higher resolutions with less computation.

- Beats other state-of-the-art systems in quality and alignment:

- Higher fidelity in reconstruction (more accurate shapes and normals).

- Better match between the input image and the generated 3D results.

- Strong user study preferences (people generally liked these results more).

- Supports flexible scaling at test time: you can run the pipeline multiple times to clean mistakes or boost resolution, improving details without retraining everything.

Why this matters:

- Artists, designers, and game developers can get high-quality 3D models with realistic materials much faster.

- The method reduces technical headaches (no heavy field evaluations or complex multi-view texture stitching).

- It opens the door to large-scale, end-to-end 3D generation that’s practical for real production.

Implications and Impact

This research moves 3D generation closer to being effortless and production-ready:

- It provides a native 3D representation (O-Voxel) that unifies shape and material, making pipelines simpler and more reliable.

- The compact latent space makes huge models practical to use, enabling fast, high-res 3D creation on modern hardware.

- It can handle real-world, complex assets—important for games, movies, AR/VR, product visualization, and digital art.

- Since the project is open-source, other researchers and developers can build on it, potentially leading to even better tools for creating and editing 3D content.

In short, this work makes generating complex, beautiful 3D models from images both faster and more reliable, bringing high-end 3D creation closer to everyday use.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps that remain unresolved and could guide future research:

- Formal guarantees for the Flexible Dual Grid: no analysis of watertightness, manifoldness, or stability of the modified QEF solution under degenerate or sparse Hermite data; sensitivity of λ-weights and failure modes on sharp corners and boundaries are not quantified.

- Mesh quality assessment is missing: no statistics on triangle aspect ratios, self-intersections, flipped normals, or suitability for downstream CAD/simulation/3D‑printing; no robustness measures under mesh decimation or simplification.

- Minimal resolvable feature size and thin-structure recall are not characterized as a function of voxel resolution, sparsity, and early-pruning thresholds; no calibration for recall/precision of extremely thin wires, fabrics, or perforations.

- No adaptive spatial refinement: the method uses a regular sparse grid without octree/multigrid adaptivity; how to scale to very large assets/scenes, or concentrate resolution on high-curvature/high-texture regions, remains open.

- Limited PBR material model: only basecolor, metallic, roughness, and opacity are supported; normal maps, specular/reflectance color, index of refraction, clearcoat, sheen, anisotropy, emission, subsurface scattering, transmission, and displacement are not modeled.

- Translucency/refraction are under-specified: opacity alone cannot reproduce refractive/transmissive effects; the renderer (split-sum) omits caustics/refraction—no metrics or ablations quantify fidelity on glass/liquids/SSS.

- Potential loss of high-frequency texture detail: volumetric attributes sampled at voxel centers and reconstructed via trilinear interpolation may blur fine decals and edges; anti-aliasing/super-resolution strategies and anisotropic filtering are not explored.

- No representation of multi-material mixtures within a voxel (e.g., fractional occupancy or learned mixture weights); how to avoid averaging artifacts at material boundaries is not addressed.

- Illumination–material disentanglement is not evaluated: the pipeline aims to recover intrinsic PBR from a single lit image, but there is no controlled study under varying/unknown lighting or shadow/specular confounds.

- Generalization to in-the-wild photos is unclear: evaluation uses AI-generated prompts and synthetic renders; performance on real photos, lighting diversity, and camera metadata noise is not assessed.

- Ambiguity and diversity in single-image 3D: no analysis of multi-modal outputs, diversity vs. fidelity trade-offs, or mechanisms for sampling multiple plausible completions with uncertainty estimates.

- Interior structure evaluation is limited: while internal geometry is emphasized, there is no dataset/metric for interior material accuracy or visibility-driven quality; current metrics focus on externals or normals.

- Conversion robustness from non-ideal inputs: behavior on noisy/degenerate meshes, non-triangular primitives (NURBS), or scan-derived point clouds is not studied; direct ingestion of non-mesh 3D (point clouds, depth) is unsupported.

- Differentiability of the asset↔O‑Voxel conversion is not specified: end-to-end gradient flow through dual-vertex placement and quad splitting for fine-tuning/editing remains an open engineering and optimization question.

- Controllability/editability is not explored: part-aware edits, global material sliders (e.g., “increase roughness”), text-driven edits, or localized painting in the latent space are not demonstrated.

- Scene-scale generation is out of scope: multi-object scenes, layout, backgrounds, global illumination across objects, and memory/time scaling for large scenes are not addressed.

- Animation/rigging are unsupported: no handling of skeletons, skin weights, blend shapes, or deformation-aware materials; suitability of O‑Voxel for dynamic assets is unknown.

- Conditioning breadth is limited: reliance on DINOv3 image features; text-only, multi-view, depth/normal conditioning, or joint text–image controls are not benchmarked.

- Token budget vs. fidelity trade-offs lack a principled study: no Pareto curves across categories (e.g., cables vs. organic shapes), nor per-category failure analysis; optimal latent dimensionality is not analyzed.

- Early-pruning upsampler risks irreversible omissions: there is no calibration of false-negative rates, uncertainty-aware gating, or refinement loops to recover pruned fine structures.

- Compute/memory footprint transparency: detailed VRAM usage across resolutions (5123→15363), batch-size limits, and performance on commodity GPUs are not reported; scalability beyond 15363 is untested.

- Benchmark comparability gaps: runtime comparisons mix hardware (H100 vs. A100); many baselines lack material support; standardized PBR realism metrics and controlled render-equalized comparisons are missing.

- Export/baking to standard DCC pipelines (USD/GLTF) is under-detailed: normal/displacement map baking, UV unwrapping quality, seam management, and cross-engine material parity are not evaluated.

- Data quality and governance: biases and license compliance in Objaverse/ABO/HSSD/TexVerse subsets, potential memorization or asset leakage, and watermarking/safety mitigation are not discussed.

- Test-time cascaded scaling lacks theory: no convergence guarantees, error bounds, or criteria for when cascades improve vs. accumulate artifacts; robustness to compounding discretization noise is unmeasured.

- SC‑VAE design space is not fully explored: effects of KL weight, latent dimensionality, codebook/VQ alternatives, hierarchical latents, and cross-scale skip strategies on compression/fidelity are not ablated.

- Multi-view conditioning remains open: how performance scales with 2–8 images, pose estimation under unknown cameras, and fusion strategies (vs. single-image) are not studied.

Glossary

- AdaLN-single: A lightweight adaptive layer normalization variant used to condition transformer blocks. Example: "All our DiT modules employ the AdaLN-single modulation"

- AdamW: An optimizer that decouples weight decay from the gradient-based update to improve generalization. Example: "All models are trained using AdamW (learning rate , weight decay $0.01$) with classifier-free guidance (drop rate $0.1$)."

- Bidirectional Point-to-Mesh Distance: A metric computing distances in both directions between point samples and mesh surfaces to assess geometric fidelity. Example: "Mesh Distance (MD) calculated as Bidirectional Point-to-Mesh Distance with F1-score"

- Binary Cross Entropy (BCE): A loss function commonly used for binary classification and mask prediction tasks. Example: "Mean-Squared-Error (MSE) and Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) losses are applied"

- Chamfer Distance: A symmetric distance between point sets, often used to evaluate 3D reconstruction quality. Example: "Chamfer Distance with F1-score computed on point clouds"

- Classifier-free guidance: A sampling technique that improves conditional generation by combining conditional and unconditional model predictions. Example: "with classifier-free guidance (drop rate $0.1$)."

- CLIP score: A text-image alignment metric based on the CLIP model’s joint embedding space. Example: "Visual alignment is measured with the CLIP score"

- ConvNeXt-style: A convolutional block design simplifying traditional residual blocks for efficiency and performance. Example: "following the ConvNeXt-style simplification."

- DiT (Diffusion Transformer): A diffusion model architecture built on transformers for generative modeling. Example: "We adopt full DiT-based architectures trained with the flow matching paradigm"

- DINOv3-L: A large self-supervised vision transformer used to extract robust image features. Example: "Image conditioning features are extracted from DINOv3-L."

- Dual Contouring (DC): A surface extraction algorithm using Hermite data on grid edges to reconstruct meshes. Example: "This formulation is inspired by Dual Contouring (DC)"

- Flexible Dual Grid: A dual-grid surface representation that enables robust handling of arbitrary topology in voxel structures. Example: "The O-Voxel can robustly represent surfaces with arbitrary topology, owing to its Flexible Dual Grid formulation."

- Flood-fill procedure: A region-growing algorithm often used to identify connected components; here, cited as a costly step avoided. Example: "SDF evaluation, flood-fill procedure, and iterative optimization are not needed."

- Flow matching: A generative modeling paradigm that learns transport maps between distributions via differential equations. Example: "trained with the flow matching paradigm"

- Gaussians (3D Gaussians): Explicit 3D primitives representing geometry/appearance as anisotropic Gaussian functions. Example: "merge the generated mesh and 3D Gaussians for asset extraction."

- Hermite data: Edge-associated intersection points and normals used for precise surface positioning. Example: "with edges tagged by Hermite data (\ie, intersection points and normals)."

- Iso-surface fields: Scalar fields whose constant-value level sets define surfaces (e.g., SDF iso-surfaces). Example: "iso-surface fields (\eg, signed distance function, Flexicubes)"

- KL loss: The Kullback–Leibler divergence term in VAEs that regularizes the posterior toward a prior. Example: "with direct O-Voxel reconstruction loss and KL loss."

- LPIPS: A learned perceptual image metric correlating with human judgments of visual similarity. Example: "augmented with SSIM and LPIPS terms on normals."

- Mean-Squared-Error (MSE): A standard regression loss measuring squared error between predictions and targets. Example: "Mean-Squared-Error (MSE) and Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) losses are applied"

- Mipmap: A multiscale texture representation used to efficiently sample textures with reduced aliasing. Example: "using UV coordinates and appropriate mipmap levels."

- NeRF (Neural Radiance Fields): A neural representation that models view-dependent radiance for photorealistic rendering. Example: "NeRF integrates geometry and appearance in a radiance field"

- Non-manifold geometry: Geometric configurations that violate manifold conditions (e.g., edges shared by more than two faces). Example: "handling open surfaces, non-manifold geometry, and enclosed interior structures."

- nvdiffrec split-sum renderer: A physically-based renderer component from nvdiffrec used for efficient PBR rendering. Example: "Split-sum renderer from nvdiffrec is used for PBR asset rendering."

- Occupancy fields: Implicit representations indicating whether points in space are inside or outside an object. Example: "such as occupancy fields"

- O-Voxel: An omni-voxel sparse representation encoding both geometry and materials with instant mesh conversion. Example: "O-Voxel is an omni-voxel representation that encodes both geometry and appearance."

- Perceiver-style architectures: Models that process unordered sets via cross-attention to learn from high-dimensional inputs. Example: "inspired by the Perceiver-style architectures"

- Physically-Based Rendering (PBR): A rendering approach using physically grounded material parameters for realism. Example: "physically-based rendering (PBR) parameters"

- Point-wise MLP: A multilayer perceptron applied per voxel/point to enrich features without spatial convolution. Example: "incorporating point-wise MLPs for richer feature transformation."

- PSNR: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio, a distortion metric for image/attribute reconstruction quality. Example: "surface quality metrics using PSNR and LPIPS of rendered normal maps."

- Quadratic Error Function (QEF): An optimization objective used to position dual vertices by minimizing squared distances to planes/lines. Example: "the following quadratic error function (QEF):"

- Radiance field: A function describing emitted radiance at 3D locations and viewing directions. Example: "integrates geometry and appearance in a radiance field"

- RoPE (Rotary Position Embedding): A positional encoding technique enabling better extrapolation in transformers. Example: "Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE)"

- Signed Distance Functions (SDF): Scalar fields giving the signed distance to the nearest surface, positive outside and negative inside. Example: "Signed Distance Functions (SDF)"

- Sparse convolution: Convolution operations specialized for data with sparse spatial occupancy to reduce computation. Example: "employs a fully sparse-convolutional network"

- Sparse DiT: A diffusion transformer operating over sparse latent tokens or grids for efficient 3D generation. Example: "A sparse DiT predicts material latents"

- SSIM: Structural Similarity Index, a perceptual metric assessing structural fidelity between images. Example: "augmented with SSIM and LPIPS terms on normals."

- Submanifold convolution: A sparse convolution variant that preserves sparsity by restricting outputs to active sites. Example: "Submanifold convolution to further improve training speed."

- Trilinear interpolation: Interpolation within 3D grids using linear interpolation along each axis. Example: "via trilinear interpolation of the neighboring voxel attributes."

- ULIP-2: A multimodal alignment model used to assess cross-modal (image–3D) similarity. Example: "multimodal models ULIP-2 and Uni3D are employed"

- Uni3D: A multimodal model evaluating alignment between images and 3D representations. Example: "multimodal models ULIP-2 and Uni3D are employed"

- UV coordinates: 2D parameterizations mapping surface points to texture space for sampling textures. Example: "using UV coordinates and appropriate mipmap levels."

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): A generative model with an encoder-decoder and latent probabilistic regularization. Example: "We apply a VAE to learn a proper latent space from O-Voxel data."

- Watertight: A property of meshes being closed without holes, important for certain reconstruction methods. Example: "free from the watertight and manifold constraints"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical applications that can be deployed now, given the open-source release and the paper’s demonstrated runtimes, fidelity, and bidirectional conversion between meshes and O-Voxel.

- Image-to-3D asset generation for DCC and game engines

- Sector(s): Gaming, VFX/animation, AR/VR, e-commerce

- Tools/Workflow: Blender/Unreal/Unity plugin that takes a single reference image and outputs a high-fidelity, PBR-textured mesh via O‑Voxel + SC‑VAE + sparse DiT; direct export to glTF/USD with PBR maps; native end-to-end generation removes multi-view baking and alignment

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of pretrained weights; GPU required for fast inference (consumer GPUs slower than H100/A100); domain-specific fine-tuning may be needed for certain product categories

- Shape‑conditioned PBR texturing for existing meshes (UV‑agnostic volumetric attributes)

- Sector(s): Gaming, design, e-commerce product retexturing

- Tools/Workflow: Use Stage‑3 material generator to synthesize PBR materials aligned to input geometry; bake volumetric attributes to UV textures for downstream rendering

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Texture baking/export toolchain (glTF/USD); adding extra PBR channels (e.g., normal/specular/clearcoat) may be needed for some industries

- Topology‑agnostic mesh repair and retopology

- Sector(s): Asset QA pipelines, marketplaces, VFX/game outsourcing

- Tools/Workflow: Mesh→O‑Voxel→Mesh conversion to clean non‑manifold, open surfaces, and preserve sharp features via dual grid and splitting weights; batch asset sanitization

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Fidelity depends on chosen voxel resolution; very complex self‑intersections may need manual inspection

- High‑ratio 3D asset compression and CDN delivery

- Sector(s): Web3D, e‑commerce viewers, cloud gaming

- Tools/Workflow: Store SC‑VAE latents (e.g., ~9.6K tokens for 1024³ assets) and decode on client to mesh + PBR; progressive streaming via sparse structure occupancy masks

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Runtime decoder on client (WebGPU/engine integration); new packaging/format conventions (e.g., glTF/USD extensions); client compute/energy constraints

- Photoreal synthetic data generation for vision

- Sector(s): Robotics, retail vision, industrial inspection ML

- Tools/Workflow: Generate diverse, physically consistent PBR assets (including translucency) and render under varied lighting for training detection/pose/segmentation models

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Physics not modeled (use external engines for dynamics); require annotation pipelines and domain randomization for robust training

- Rapid product digitization from catalog images

- Sector(s): E‑commerce, advertising

- Tools/Workflow: Batch image→3D conversion with native PBR materials; direct AR-ready assets; relighting ability for consistent product pages

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Single-view ambiguity mitigated by human QA or optional multi-view inputs; brand IP clearance and dataset licensing compliance

- Pipeline acceleration by eliminating multi‑view baking/alignment

- Sector(s): VFX/game content production

- Tools/Workflow: Replace multi-view texture fusion with native 3D material generation; reduce ghosting/seams; unify geometry/appearance in one latent space for faster iteration

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Adoption within studio pipelines (asset managers, render farms); training/fine-tuning with studio style guides

- Education: hands‑on modules for 3D geometry/materials

- Sector(s): Education (graphics, CAD, game dev)

- Tools/Workflow: Classroom demos of dual grid, DC-inspired QEF, splitting weights, and volumetric PBR; students explore topology and material interplay

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Open-source code availability; CPU suffices for conversions, GPUs improve generation speed

- Transparent/glassy material authoring with relighting

- Sector(s): Architecture, industrial/product design, AR content

- Tools/Workflow: Use opacity channel with PBR for glass/plastic assets; quick relighting in design reviews and interactive demos

- Assumptions/Dependencies: For high‑fidelity glass, engines may need additional PBR attributes (IOR/refraction/clearcoat normal)

Long‑Term Applications

Below are applications that benefit from further research, scaling, standardization, or engineering for production.

- Scene‑level native 3D generation and editing

- Sector(s): AEC, gaming open worlds, digital twins

- Tools/Workflow: Extend O‑Voxel to multi‑asset scene graphs; consistent materials and global lighting; generate interiors/exteriors with enclosed structures

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Large scene datasets, semantics and physics integration, memory scaling strategies

- On‑device, real‑time image‑to‑3D for consumers

- Sector(s): Mobile AR/social, creator tools

- Tools/Workflow: Distill/quantize SC‑VAE and sparse DiTs; WebGPU/browser decoders; capture→3D pipeline on phones for instant AR objects

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Model compression/acceleration; energy budgets; privacy and on-device provenance

- Standardization of O‑Voxel/latent formats

- Sector(s): Software/standards

- Tools/Workflow: glTF/USD extensions for O‑Voxel and SC‑VAE latents; progressive streaming; runtime decoders and authoring tools across engines

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Industry/community buy-in; security considerations; backward compatibility and ecosystem testing

- 3D asset provenance, watermarking, and IP governance

- Sector(s): Policy/regulation, marketplaces

- Tools/Workflow: Embed provenance in latents; robust mesh watermarking across topology changes; transparent dataset/model cards; automated IP compliance checks

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Legal frameworks and standards; watermark robustness under retopology/decimation; interoperable metadata

- Material understanding and inverse rendering with volumetric latents

- Sector(s): Academia (graphics/vision), industrial metrology

- Tools/Workflow: Combine O‑Voxel PBR channels with differentiable rendering to estimate materials from sparse imagery; refine roughness/metallic/opacity recovery

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi‑view capture or controlled lighting; ground-truth PBR datasets; compute for optimization

- Robotics and embodied AI simulations with photoreal assets

- Sector(s): Robotics, autonomous systems

- Tools/Workflow: Generate task‑specific asset packs with realistic materials; integrate with physics engines for contact and dynamics; reduce sim‑to‑real domain gap

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Physics parameterization (mass, friction, restitution); validated material→sensor models; domain randomization pipelines

- Industrial part digitization with interior structure preservation

- Sector(s): Manufacturing, NDT, maintenance

- Tools/Workflow: Represent enclosed cavities and non‑manifold features; fuse with CT/scan data; digital twins for flow/thermal analyses and maintenance training

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Alignment of O‑Voxel with volumetric sensor grids; additional attributes (density, emissivity); very high resolution requirements

- Eco‑efficiency tracking and compute budgeting in 3D pipelines

- Sector(s): Energy/sustainability in AI and media production

- Tools/Workflow: Exploit compact latents to set per‑asset carbon budgets; dashboards for token counts vs. quality; energy-aware scheduling in render farms

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate energy measurement tooling; organizational buy‑in; quality metrics tied to business outcomes

- Collaborative 3D co‑creation with multimodal LLMs

- Sector(s): Software/content platforms, education

- Tools/Workflow: Language-driven constraints specify geometry/material goals; O‑Voxel generator produces assets; style libraries and iterative edits

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable multimodal integration, safety filters, latent versioning, team-aware asset governance

- Web‑scale 3D search and retrieval using compact latents

- Sector(s): Search/e‑commerce/marketplaces

- Tools/Workflow: Index SC‑VAE latent tokens for fast nearest‑neighbor retrieval; search‑by‑image for 3D assets with PBR similarity

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Scalable indexes and embeddings; dataset licensing compliance; quality controls and deduplication across variants

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.