Efficiently Reconstructing Dynamic Scenes One D4RT at a Time (2512.08924v1)

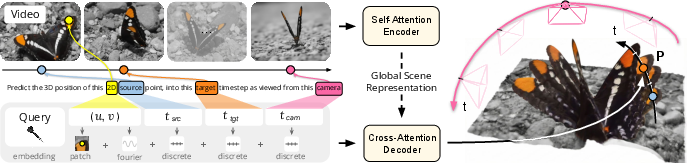

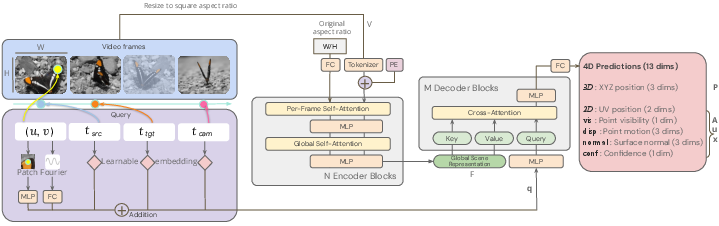

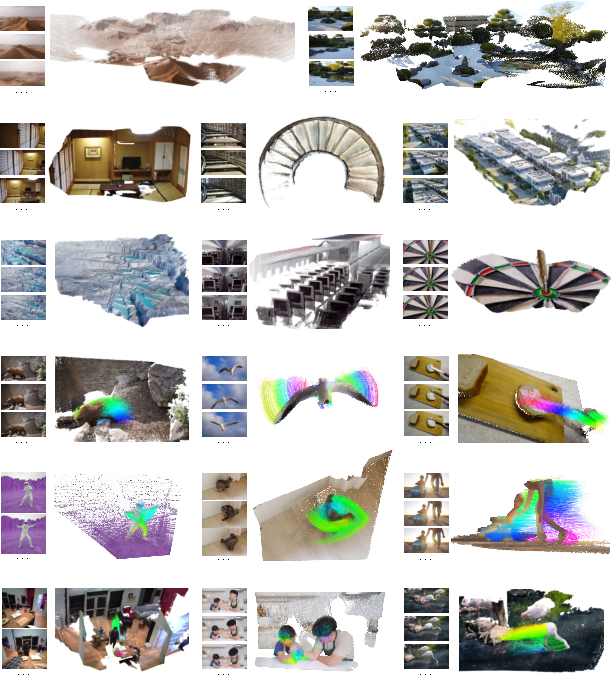

Abstract: Understanding and reconstructing the complex geometry and motion of dynamic scenes from video remains a formidable challenge in computer vision. This paper introduces D4RT, a simple yet powerful feedforward model designed to efficiently solve this task. D4RT utilizes a unified transformer architecture to jointly infer depth, spatio-temporal correspondence, and full camera parameters from a single video. Its core innovation is a novel querying mechanism that sidesteps the heavy computation of dense, per-frame decoding and the complexity of managing multiple, task-specific decoders. Our decoding interface allows the model to independently and flexibly probe the 3D position of any point in space and time. The result is a lightweight and highly scalable method that enables remarkably efficient training and inference. We demonstrate that our approach sets a new state of the art, outperforming previous methods across a wide spectrum of 4D reconstruction tasks. We refer to the project webpage for animated results: https://d4rt-paper.github.io/.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about (the big idea)

The paper introduces D4RT, a computer program that takes a regular video and builds a moving 3D model of everything in it. Think of it as turning a flat movie into a 3D “flipbook” you can pause, rewind, and look at from different angles—even when things in the video are moving.

What questions the researchers wanted to answer

They asked:

- Can we understand the shape of a scene and how it moves over time (3D + time = “4D”) using just a video?

- Can one simple system do many jobs at once—like estimating depth, following points as they move, and figuring out where the camera is and how it’s zoomed—without needing lots of separate parts?

- Can we make it fast enough to use on long or complex videos?

How D4RT works (in everyday language)

Instead of trying to reconstruct every pixel of every frame all at once (which is slow), D4RT uses a “ask only what you need” strategy.

Here’s the basic plan:

- First, a smart “encoder” watches the whole video and builds a compact memory of the scene. You can imagine it as a mental map that knows what’s where and how things move.

- Then, a lightweight “decoder” answers questions about specific points. A “question,” or query, looks like this: “For the pixel at position (u, v) in frame A, where is that point in 3D at time B, and how does it look from camera C?”

Why that’s powerful:

- You can ask about any pixel, at any time, from any camera viewpoint. That means you can get:

- Depth maps (how far things are)

- 3D point clouds (a 3D “spray” of points making up the scene)

- Point tracks (following the same point as it moves through time)

- Camera setup (where the camera is, how it’s turned, and how zoomed-in it is)

Two small tricks make D4RT work well:

- The query includes a tiny image patch (like a 9×9 crop) around the pixel. This helps the model keep crisp edges and fine details.

- To figure out camera motion between two frames, the model predicts the same 3D points in two “reference views” and then computes the rigid motion that lines them up (like overlaying two constellations of stars to see how one shifted). This is a quick math step known in computer vision but explained here as “find how one set of points needs to rotate and move to match the other.”

Tracking every pixel efficiently:

- Naively, tracking all pixels across all frames would be too many questions to ask. D4RT speeds this up with an “occupancy grid,” which keeps track of which pixels are already covered by existing tracks, so it doesn’t re-do work. This cuts the cost by 5–15× in practice.

What they found (and why it matters)

The researchers tested D4RT on several tough benchmarks and real videos. In simple terms:

- It’s accurate:

- It beats or matches the best previous systems at building 3D point clouds, estimating depth across whole videos, figuring out camera position/orientation, and tracking points in 3D—even when objects are moving.

- It’s fast:

- For camera pose (where the camera is and where it’s looking), D4RT runs over 200 frames per second in their tests—much faster than many popular methods—while being more accurate.

- For 3D tracking, it can follow far more points per second than previous approaches (often 18–300× more).

- It’s unified:

- One interface handles many tasks (depth, 3D tracks, point clouds, camera intrinsics/extrinsics) for both static scenes and scenes with motion.

- It stays sharp:

- That small appearance patch in each query helps preserve fine details and cleaner object boundaries.

Why this is important (future impact)

Because D4RT can quickly and accurately turn ordinary videos into moving 3D models, it unlocks a lot of possibilities:

- Video editing and VFX: Remove or rearrange objects, or change the camera angle after filming.

- AR/VR: Build immersive scenes from phone videos and walk around inside them.

- Robotics and self-driving: Understand the 3D world and moving objects from onboard cameras in real time.

- Sports and education: Analyze motion—of players, animals, or experiments—in 3D, not just 2D.

Most importantly, D4RT shows a new way to think about 4D understanding: don’t try to decode everything everywhere; build a strong scene memory once, then answer targeted questions on demand. That makes the system simpler, faster, and more flexible, and it handles moving scenes far better than many older methods.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future research could address.

- Intrinsics estimation assumptions: The method derives focal lengths assuming a pinhole camera with principal point at (0.5, 0.5); the impact of non-centered principal points, rolling shutter, zoom, and changing intrinsics within a video is not quantified or validated.

- Distortion handling: While a non-linear refinement for distortion (e.g., fisheye) is mentioned, there is no evaluation of intrinsics recovery under significant lens distortion or unusual projection models.

- Extrinsics under dynamics: Camera extrinsics are recovered via Umeyama between two sets of predicted 3D points without an explicit dynamic/background mask or RANSAC; robustness to moving objects influencing pose estimation is not analyzed.

- Absolute metric scale: The approach normalizes by mean depth and reports metrics after alignment; it remains unclear whether D4RT can recover accurate metric scale and units without ground-truth intrinsics or external scale cues.

- Streaming/online inference: The encoder processes the entire video clip to produce a global scene representation; incremental or causal updates for streaming or very long videos are unexplored.

- Scalability to long sequences: The model is trained on 48-frame clips at 256×256; memory, accuracy, and latency for longer videos or higher frame counts are not characterized.

- High-resolution inference: Inputs are resized to square resolution, with aspect ratio embedded as a token; the accuracy, artifacts, and computational cost at native high resolutions and extreme aspect ratios are not evaluated.

- Query independence trade-offs: Queries are decoded independently to avoid performance drops with inter-query attention; mechanisms to enforce cross-query geometric consistency (e.g., constraints that couple tracks or points) are not explored.

- Occlusion handling details: The “Visible(P)” function used to mark occupancy and accelerate dense tracking is not specified or evaluated; how visibility is predicted, calibrated, and affects completeness of dense reconstruction remains unclear.

- Long-occlusion re-identification: Robustness of 3D tracks across long-term occlusions, disocclusions, and re-entries is not measured, nor is identity consistency when points leave and re-enter the field of view.

- Uncertainty calibration: A confidence penalty is trained, but the calibration quality of predicted uncertainties (e.g., reliability diagrams, negative log-likelihood) is not analyzed.

- Ground-truth supervision sources: The paper does not specify how accurate 3D ground truth (positions, normals, visibility, motion) is obtained for dynamic scenes in all training datasets; sensitivity to noisy or missing supervision is unknown.

- Self-supervised training: Feasibility of training with self-supervision (e.g., photometric consistency, cycle consistency) to reduce reliance on labeled 3D data is not investigated.

- Domain generalization: Performance on truly in-the-wild consumer videos (handheld, low-light, heavy compression, severe motion blur, rolling shutter) is not systematically evaluated beyond a few qualitative examples.

- Dataset bias and reproducibility: The training mixture includes internal datasets; the effect of dataset composition on generalization and the ability for others to reproduce results without internal data are open issues.

- Robustness to reflective/translucent/textureless regions: Failure modes with specular highlights, transparency, and low-texture surfaces (common in dynamic scenes) are not analyzed.

- Camera intrinsics changes mid-video: Although the method claims support for changing intrinsics, there is no targeted benchmark or ablation on videos with zoom, variable focal length, or dynamic principal point shifts.

- Patch embedding design: The local 9×9 RGB patch improves performance, but the optimal patch size, multi-scale context, and sensitivity to large viewpoint changes are not studied; quantitative subpixel precision is only claimed, not measured.

- Dense reconstruction completeness: The occupancy-grid tracking acceleration claims 5–15× speedups, but completeness (percentage of pixels successfully tracked/reconstructed) and error accumulation from skipped queries are not reported.

- Pose estimation robustness: The pose solver relies on a single rigid transform; incorporating robust estimators (e.g., RANSAC, dynamic masking) and evaluating pose accuracy under high dynamic ratios are open directions.

- Global consistency across time: Without inter-query coupling, the method may produce small temporal inconsistencies; techniques to enforce physically plausible trajectories (e.g., smoothness, rigidity priors per object) are untested.

- Rolling shutter modeling: The framework does not model row-dependent exposure timing; assessing impact on geometry and tracking for rolling-shutter cameras is an open question.

- Use of predicted motion vectors: Motion supervision is mentioned, but how the predicted motion vectors are used downstream (e.g., for dynamic segmentation, articulation modeling) is not explored.

- Conversion to structured 3D outputs: Lifting point clouds/tracks to meshes, dynamic radiance fields, or articulated canonical models is left unexplored; pipelines for post-processing (e.g., meshing, temporal fusion) are not provided.

- Evaluation metrics coverage: Beyond AJ, APD3D, L1, and depth/pose errors, there is no assessment of reconstruction completeness, topological correctness, edge fidelity, or temporal stability under dynamic occlusions.

- Memory footprint and tokenization: The size of the global scene representation F (N×C), its memory footprint, and scaling behavior with video length/resolution are not detailed; memory-efficient variants remain open.

- Deployment constraints: Throughput numbers are on A100; performance on resource-constrained hardware (laptops, mobile GPUs/NPUs) and energy consumption are not reported.

- Multi-shot/multi-camera scenarios: Handling hard cuts, multi-camera synchronization, or scene changes is not discussed; robustness to edits common in real videos is unknown.

- Aspect ratio normalization effects: Resizing to a fixed square may distort intrinsics and geometry; empirical impact versus native-aspect tokenization without resizing is not ablated.

Glossary

- 3D surface normals: Vectors perpendicular to surfaces in 3D space, used to describe local geometry and orientation. "cosine similarity for 3D surface normals~\cite{wang2025pi};"

- 4D Reconstruction: Recovering spatial 3D structure together with time (the fourth dimension), capturing geometry and motion over video. "We demonstrate that our approach sets a new state of the art, outperforming previous methods across a wide spectrum of 4D reconstruction tasks."

- Absolute Relative Error (AbsRel): A depth evaluation metric measuring the average relative difference between predicted and ground-truth depths. "After alignment, we compute the Absolute Relative Error (AbsRel)~\cite{AbsRelErr} between the predicted and ground-truth depths."

- Absolute Translation Error (ATE): A camera pose metric quantifying the absolute difference in translation between predicted and ground-truth trajectories. "We report the Absolute Translation Error (ATE), Relative Translation Error (RPE trans), and Relative Rotation Error (RPE rot) after Sim(3) alignment with the ground truth as in \cite{zhang2024monst3r, wang2025cut3r, wang2025pi}, as well as the Pose AUC@$30$ as in \cite{wang2025vggt}."

- AdamW optimizer: A variant of Adam with decoupled weight decay, used for training deep networks. "The model is trained for 500\,k steps using the AdamW optimizer~\cite{adam, adamw} with a local batch size of 1 across 64 TPU chips, taking a total of just over 2 days to complete."

- Affine-invariant setup: An evaluation or formulation invariant to affine transformations (scaling, translation, rotation, shearing). "while the latter introduces an additional 3D translation term, following an affine-invariant setup."

- Average Jaccard (AJ): A tracking metric measuring overlap between predicted and ground-truth tracks over time. "We report standard 3D tracking metrics Average percent of points within delta error , Occlusion Accuracy (OA) and 3D Average Jaccard (AJ)."

- Average percent of points within delta error (APD_3D): A tracking metric expressing the fraction of points whose 3D error is within a threshold. "We report standard 3D tracking metrics Average percent of points within delta error , Occlusion Accuracy (OA) and 3D Average Jaccard (AJ)."

- Camera extrinsics: Parameters defining a camera’s position and orientation in the world (pose). "We next detail how camera extrinsics and intrinsics predictions are obtained."

- Camera intrinsics: Parameters defining a camera’s internal geometry (e.g., focal length, principal point). "We next detail how camera extrinsics and intrinsics predictions are obtained."

- Cartesian product: The set of all combinations across multiple parameter sets, used here to enumerate query configurations. "A diverse set of geometry-related tasks can be inferred by querying the Cartesian product of the respective entries."

- COLMAP: A popular SfM/MVS pipeline for camera pose estimation and reconstruction. "The standard pipeline exemplified by COLMAP~\cite{schonberger2016structure} incrementally estimates and optimizes sparse geometry and camera poses."

- Confidence penalty: A loss term that penalizes overconfident predictions to improve robustness. "We finally incorporate a confidence penalty where additionally weights the 3D point error~\cite{kendall2017uncertainties}."

- Cosine similarity: A measure of similarity between two vectors based on the cosine of the angle between them. "cosine similarity for 3D surface normals~\cite{wang2025pi};"

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism where query tokens attend to keys/values from another sequence or representation. "The decoder is a small cross-attention transformer."

- Feedforward model: A non-iterative model that produces outputs in a single pass without test-time optimization. "This paper introduces D4RT, a simple yet powerful feedforward model designed to efficiently solve this task."

- Fisheye: A lens/camera distortion model with strong radial distortion producing wide-angle images. "Camera models with distortion (\eg, fisheye) can also be seamlessly incorporated by adding a non-linear refinement step on top of the initial estimation~\cite{zhang2002flexible}."

- Fourier feature embedding: Encoding coordinates with sinusoidal features to improve learning of high-frequency detail. "A query token is first constructed by adding the Fourier feature embedding~\cite{AttentionIsAllYouNeed} of the 2D coordinates to the learned discrete timestep embeddings..."

- Global attention: Attention across all tokens (frames/positions), capturing long-range context. "VGGT~\cite{wang2025vggt} later scaled this approach beyond pairs by using a Vision Transformer~\cite{dosovitskiy2021} with global attention."

- Global Scene Representation: A latent feature representation summarizing the entire video’s scene. "The video is first processed by a powerful encoder producing the Global Scene Representation ."

- Global self-attention: Self-attention applied across the entire token sequence to aggregate global context. "Our encoder is based on the Vision Transformer~\cite{dosovitskiy2021} with interleaved local frame-wise, and global self-attention layers~\cite{wang2025vggt}."

- L1 loss: The mean absolute error loss, robust to outliers compared to squared error. "The primary supervision signal is derived from an loss applied to the normalized 3D point position $#1{P}$."

- Multi-View Stereo (MVS): A method to reconstruct dense 3D geometry from multiple images with known poses. "Classical approaches to 3D reconstruction are fundamentally anchored in multi-view geometry, specifically Structure-from-Motion (SfM)~\cite{hartley2003multiple, oliensis2000critique} and Multi-View Stereo (MVS)~\cite{furukawa2015stereo,schonberger2016pixelwise}."

- Occupancy grid: A spatio-temporal grid marking visited/visible pixels to avoid redundant computation. "We introduce \cref{alg:track_all_pixels} which exploits spatio-temporal redundancy using an occupancy grid to speed this procedure up significantly."

- Occlusion Accuracy (OA): A metric assessing whether a model correctly predicts occlusions over time. "We report standard 3D tracking metrics Average percent of points within delta error , Occlusion Accuracy (OA) and 3D Average Jaccard (AJ)."

- Pinhole camera model: An idealized camera model without lens distortion, projecting 3D points through a single point. "Assuming a pinhole camera model with a principal point at , we get focal length parameters as follows:"

- Pose AUC@30: Area Under the Curve metric for pose accuracy up to a 30-degree threshold. "as well as the Pose AUC@$30$ as in \cite{wang2025vggt}."

- Principal point: The projection of the camera center onto the image plane; the center of the image in the pinhole model. "Assuming a pinhole camera model with a principal point at , we get focal length parameters as follows:"

- Relative Rotation Error (RPE rot): A metric quantifying rotational discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth camera motion. "We report the Absolute Translation Error (ATE), Relative Translation Error (RPE trans), and Relative Rotation Error (RPE rot) after Sim(3) alignment..."

- Relative Translation Error (RPE trans): A metric quantifying translational discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth camera motion. "We report the Absolute Translation Error (ATE), Relative Translation Error (RPE trans), and Relative Rotation Error (RPE rot) after Sim(3) alignment..."

- Rigid transformation: A transformation preserving distances and angles (rotation and translation, possibly reflection). "We therefore only need to find the rigid transformation between them, which can be efficiently derived through Umeyama's algorithm~\cite{umeyama1991least} that solves a SVD decomposition."

- Scale-and-shift alignment: Alignment that uses a global scale and a global shift to compare predicted and ground-truth depths. "Specifically, we adopt two alignment settings: scale-only (S) and scale-and-shift (SS) alignment."

- Scale-only alignment: Alignment that uses only a global scale factor to compare predicted and ground-truth depths. "Specifically, we adopt two alignment settings: scale-only (S) and scale-and-shift (SS) alignment."

- Scene Representation Transformer: A transformer architecture designed to encode scene information across views/time. "D4RT is based on a simple encoder-decoder architecture inspired by the Scene Representation Transformer~\cite{srt, rust}."

- Self-attention: An attention mechanism where tokens attend to other tokens within the same sequence. "indeed, we have empirically observed major performance drops when enabling self-attention between queries in early experiments."

- Sim(3) alignment: Alignment using the similarity transform group in 3D (rotation, translation, uniform scale). "We report the Absolute Translation Error (ATE), Relative Translation Error (RPE trans), and Relative Rotation Error (RPE rot) after Sim(3) alignment with the ground truth..."

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): A matrix factorization used to solve least-squares problems and find optimal rotations/transforms. "Umeyama's algorithm~\cite{umeyama1991least} that solves a SVD decomposition."

- Spatio-temporal: Relating jointly to space and time, e.g., patches or redundancy across frames. "For the encoder, we use the ViT-g model variant with 40 layers on a spatio-temporal patch size of ."

- Structure-from-Motion (SfM): Estimating camera motion and sparse 3D structure from multiple images. "Classical approaches to 3D reconstruction are fundamentally anchored in multi-view geometry, specifically Structure-from-Motion (SfM)~\cite{hartley2003multiple, oliensis2000critique} and Multi-View Stereo (MVS)~\cite{furukawa2015stereo,schonberger2016pixelwise}."

- Umeyama's algorithm: A closed-form method to estimate a rigid (or similarity) transform between two point sets. "We therefore only need to find the rigid transformation between them, which can be efficiently derived through Umeyama's algorithm~\cite{umeyama1991least} that solves a SVD decomposition."

- Vision Transformer: A transformer architecture applied to image/video tokens for visual tasks. "Our encoder is based on the Vision Transformer~\cite{dosovitskiy2021} with interleaved local frame-wise, and global self-attention layers~\cite{wang2025vggt}."

- World coordinate system: A single, consistent 3D reference frame in which tracks and geometry are expressed. "This task measures a model's ability to predict tracks within a single, consistent world coordinate system, thereby also measuring the models' ability to implicitly change reference frames."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be built with the paper’s current capabilities: fast, feedforward monocular 4D reconstruction (depth, point clouds, dynamic point tracks, and camera intrinsics/extrinsics), a per-query decoder interface for interactive/partial decoding, and an efficient dense-tracking algorithm. Each item names likely sectors and concrete product/workflow ideas, with key assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

- Film/VFX and 3D content creation

- What you can do now:

- One-click match-moving and camera solve from a single video, including dynamic scenes (export camera intrinsics/extrinsics over time).

- Depth-aware compositing, relighting, occlusion-aware matting, and background replacement from video depth maps.

- Dynamic object tracking as 3D point trajectories to drive CG insertions or motion transfer.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- Nuke/After Effects/Blender plugins: “D4RT MatchMove,” “D4RT Depth & Tracks,” exporting per-frame camera, depth, and point tracks.

- On-demand “Query API” for interactive artist clicks to recover 3D points/trajectories without decoding entire frames.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Scale ambiguity in monocular recon requires a metric prior if absolute measurements are needed.

- Pinhole camera assumption; distortion requires a short non-linear refinement step (supported by the method).

- Throughput numbers are reported on A100-class GPUs; desktop deployment may require batching or cloud inference.

- AR content authoring and prototyping (software, media)

- What you can do now:

- Produce occlusion masks, depth layers, and camera poses from handheld video to anchor virtual content reliably even with moving objects.

- Export world-consistent point clouds for scene-aware effects in Unity/Unreal.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT Scene Packager” that ingests a smartphone clip and outputs a ready-to-import AR scene with camera track, per-frame depth, and a sparse point cloud.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- For long clips, use sliding windows or the paper’s dense-tracking loop; ensure temporal stitching across windows.

- Mobile on-device runtime likely not feasible yet; use cloud/offline pipelines.

- Robotics R&D and dynamic SLAM bootstrapping (robotics)

- What you can do now:

- Fast pose estimates (200+ FPS reported) and dynamic point trajectories for moving actors/objects; useful for perception debugging and dataset bootstrapping.

- Rapid intrinsics/extrinsics estimation for ad-hoc monocular setups in labs and testbeds.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT Visual-Odometry Assist”: a module that provides pose priors and dynamic scene flow for downstream SLAM or tracking-by-detection.

- Dataset auto-labeling for depth, camera, and 3D tracks to train/fine-tune robotic perception models.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Domain gap to robot cameras/lighting; consider fine-tuning on in-domain footage.

- Use metric priors (object sizes, IMU) to resolve scale for control loops.

- Sports analytics and broadcast enhancement (media, sports tech)

- What you can do now:

- Derive per-player/ball 3D trajectories from a single broadcast camera; overlay speed and distance metrics.

- Generate virtual replays with consistent camera tracks and depth-aware compositing.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT SportTrack” for ingesting broadcast feeds and exporting per-frame depth and actor trajectories; integrates with telestration systems.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Zoom/focus changes require robust per-frame intrinsics estimation (model supports this).

- Severe occlusions and quick pans still require QA; combine with detection/ID models for identity continuity.

- Forensics and accident reconstruction (public safety, insurance)

- What you can do now:

- Reconstruct camera trajectory and moving object tracks from dashcam/CCTV for scene analysis.

- Measure relative distances/velocities (with caveat on metric scale).

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT CaseKit” producing synchronized camera pose, depth maps, and 3D tracks; export to CAD or simulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Establish scale via known scene dimensions or GPS/IMU; document uncertainty for legal admissibility.

- Validate lens model; apply distortion refinement when non-pinhole optics are used.

- Real estate, e-commerce, and inspection (AEC, retail, drones)

- What you can do now:

- Convert walkthrough videos into world-consistent point clouds and per-frame depth for measurements and quick 3D previews.

- Track moving agents (workers/vehicles) for safety or process studies in industrial footage.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT Scan” for rapid site capture from handheld/drone videos; export to point cloud formats (PLY/PLY+pose).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- For accurate measurements, inject metric scale via a known reference or multi-sensor fusion.

- Reflective/textureless surfaces may degrade reconstruction quality; consider QA overlays.

- 3D-aware video editing and creator tools (software, creator economy)

- What you can do now:

- Depth-aware stylization and refocusing; object-aware edits using 3D tracks to maintain coherence under motion/occlusion.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT Depth Layer” and “D4RT Smart Tracks” as timeline effects that query only the edited regions/frames (leveraging independent per-query decoding to keep latency low).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Best results when edits are localized; large, full-clip dense outputs are heavier but still tractable with the occupancy-grid scheduling in the paper.

- Academic data generation and benchmarking (academia, open-source)

- What you can do now:

- Generate pseudo-labels for depth, pose, and 3D tracks to train/benchmark other models or to augment datasets (e.g., for TAPVid-3D-like tasks).

- Study query-based architectures for 4D tasks and ablate per-query decoding vs. dense decoding at scale.

- Tools/workflows that could ship:

- “D4RT Teacher” pipelines that produce supervision for student models; evaluation scripts for dynamic 4D tracking with unified outputs.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Verify domain generalization; annotate uncertainty/confidence fields (the model predicts confidence used in the loss) for safe pseudo-labeling.

Long-Term Applications

These applications are enabled by the paper’s core innovations (independent per-query decoding, unified outputs, and speed), but require further research, scaling, or ecosystem integration.

- On-device AR glasses and smartphones: real-time 4D perception (consumer electronics, software)

- Future capability:

- Continuous, on-device 4D reconstruction and dynamic correspondence for occlusion-aware AR, world-locking, and scene editing.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Requires model compression/distillation to mobile NPUs and power constraints; robust handling of extreme motion/low light; privacy-preserving on-device processing.

- Autonomous driving and mobile robotics stacks (transportation, robotics)

- Future capability:

- Replace or augment dynamic-SLAM modules with feedforward 4D perception that is robust to moving scenes, providing pose, depth, and object tracks with low latency.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Safety certification, large-scale validation across edge cases, integration with multi-sensor fusion (LiDAR, radar), hard real-time constraints, and regulatory approvals.

- Surgical and endoscopic 4D reconstruction (healthcare)

- Future capability:

- Monocular endoscope 4D mapping with tissue motion tracking for navigation, tool guidance, and documentation.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Domain adaptation to specular, deformable tissue; stringent clinical validation and regulatory approval; robust intrinsics estimation under optics with complex distortion.

- Volumetric video and free-viewpoint telepresence (media, communications)

- Future capability:

- Consumer-friendly 4D capture from a single moving camera; synthesize novel views for immersive playback and telepresence.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Requires coupling with radiance field or high-fidelity rendering; temporal consistency at high resolution; bandwidth/codec integration for streaming.

- Geometry-assisted video compression and streaming (software, standards)

- Future capability:

- Transmit camera paths, depth, and sparse 3D tracks as side information to improve compression or enable interactive refocusing and edits client-side.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Needs standardization and encoder/decoder stack changes; rigorous perceptual studies; device support.

- Multi-camera, multi-sensor 4D fusion (smart cities, industrial automation)

- Future capability:

- Joint 4D reconstruction across diverse cameras with changing intrinsics and overlapping FOVs; fuse with IMU/GPS for metric scale and drift-free maps.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Algorithmic extensions for cross-stream query aggregation; identity/track continuity; privacy and governance for public deployments.

- Markerless human motion capture and biomechanical analysis from monocular video (sports, healthcare, animation)

- Future capability:

- Full-body 3D joint trajectories under occlusions with accurate scene scale; drive avatars or estimate load/kinematics for training or rehab.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Needs integration with body models (e.g., SMPL), identity and limb constraints, and metric scaling; clinical/athletic validation.

- Safety analytics and incident prevention at scale (policy, enterprise safety)

- Future capability:

- Real-time 4D monitoring of dynamic factory/traffic scenes to preempt hazards (proximity alerts, trajectory forecasting).

- Why it’s long-term:

- High reliability under diverse conditions, strong privacy guarantees (on-prem processing, anonymization), policy compliance (GDPR/CCPA), and human-in-the-loop oversight.

- Cultural heritage and conservation with dynamic visitor flows (public sector, museums)

- Future capability:

- 4D digitization from casual videos while separating/handling dynamic crowds; accurate, scalable mapping over time.

- Why it’s long-term:

- Robustness to heavy occlusion and lighting variability; archival standards; sustainable compute/energy use for large collections.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Model availability and licensing

- The paper references an internal/large-scale training setup; deployment depends on whether weights are released, licensed for commercial use, or reimplemented by third parties.

- Compute, latency, and resolution

- Reported speeds (e.g., 200+ FPS for pose) are on A100 GPUs and often at 256×256 inputs; scaling to 4K or on-device use requires distillation, patch-based decoding strategies, or hybrid pipelines.

- Camera models and scale

- The method assumes a pinhole model and estimates intrinsics from decoded 3D points; non-pinhole lenses need an additional non-linear step. Absolute scale is not observable without priors (objects of known size, IMU/GPS).

- Domain generalization

- Performance may degrade on specialized domains (medical, thermal, night scenes, extreme motion); fine-tuning and data curation are advised.

- Robustness to occlusions and reflectance

- While dense tracking with an occupancy grid improves coverage, strong occlusions, motion blur, reflective/textureless surfaces, and rolling shutter can still cause failure modes.

- Privacy, ethics, and governance

- 3D tracking of people/objects from consumer or public videos intersects with privacy regulations and ethical use; deployers should implement consent, on-device processing where possible, and minimization/retention policies.

These applications leverage the paper’s core innovations: a unified 4D interface via on-demand queries, independent per-query decoding for interactive and scalable inference, and a pipeline that estimates depth, dynamic correspondences, and camera parameters without multi-stage optimization.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.