Can Vibe Coding Beat Graduate CS Students? An LLM vs. Human Coding Tournament on Market-driven Strategic Planning (2511.20613v1)

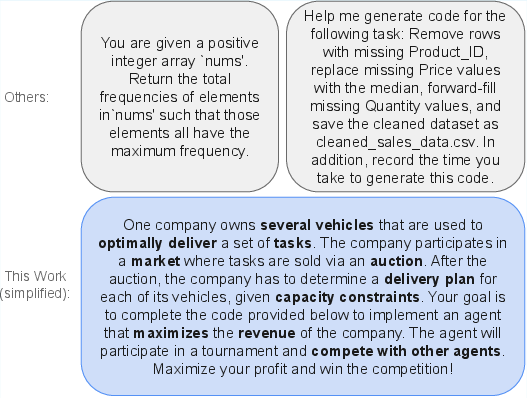

Abstract: The rapid proliferation of LLMs has revolutionized AI-assisted code generation. This rapid development of LLMs has outpaced our ability to properly benchmark them. Prevailing benchmarks emphasize unit-test pass rates and syntactic correctness. Such metrics understate the difficulty of many real-world problems that require planning, optimization, and strategic interaction. We introduce a multi-agent reasoning-driven benchmark based on a real-world logistics optimization problem (Auction, Pickup, and Delivery Problem) that couples competitive auctions with capacity-constrained routing. The benchmark requires building agents that can (i) bid strategically under uncertainty and (ii) optimize planners that deliver tasks while maximizing profit. We evaluate 40 LLM-coded agents (by a wide range of state-of-the-art LLMs under multiple prompting methodologies, including vibe coding) against 17 human-coded agents developed before the advent of LLMs. Our results over 12 double all-play-all tournaments and $\sim 40$k matches demonstrate (i) a clear superiority of human(graduate students)-coded agents: the top 5 spots are consistently won by human-coded agents, (ii) the majority of LLM-coded agents (33 out of 40) are beaten by very simple baselines, and (iii) given the best human solution as an input and prompted to improve upon, the best performing LLM makes the solution significantly worse instead of improving it. Our results highlight a gap in LLMs' ability to produce code that works competitively in the real-world, and motivate new evaluations that emphasize reasoning-driven code synthesis in real-world scenarios.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a simple but important question: can “vibe coding” with LLMs—where you describe what you want in plain English and the AI writes the code—beat real graduate students at building smart, strategic software? To test this, the authors ran a big coding tournament on a realistic problem: delivery companies bidding to carry packages and planning routes to make the most profit.

What the paper is about

The main topic is a new, tougher benchmark (test) for code generated by AI. Instead of easy problems checked by unit tests, this benchmark is a real-world challenge that mixes:

- Competing in auctions to win delivery jobs,

- Planning routes with limited vehicle capacity,

- Making money while managing costs,

- Thinking ahead about competitors and future tasks.

The authors compare LLM-coded agents (software made by AI) against human-coded agents (software made by graduate students and researchers) in thousands of head-to-head matches.

What questions the researchers wanted to answer

The paper focuses on questions a 14-year-old can relate to:

- Do LLMs that write working code also perform well on complicated, real-world problems?

- Can vibe coding produce software that plays smart in competitive environments?

- Are LLMs already as good as graduate-level coders when strategy, planning, and optimization matter?

How the paper was done

Here is the approach, explained with everyday ideas:

- The challenge: Imagine several delivery companies in different countries. Each company has a few trucks with limited space. Jobs (packages to be picked up and delivered) are sold through an auction. Companies bid for each job, trying to charge enough to make money but not so much that they lose the job to a cheaper competitor. After winning jobs, they must plan routes to pick up and deliver everything, without breaking rules like “don’t carry more weight than the truck can handle” and “pick up before you deliver.”

- The auction type: It’s a “reverse first-price sealed-bid auction.” Reverse means the lowest price wins (because the buyer wants the cheapest delivery). First-price means the winner gets paid exactly what they bid. Sealed-bid means each company submits a hidden bid; after the auction ends, bids are revealed. Companies also see past bids, so they can try to learn how rivals think.

- Costs and strategy: Companies try to balance revenue (money earned from winning bids) with costs (fuel per kilometer). Good strategy includes ideas like:

- Marginal cost: the extra cost of adding one more job to your current plan.

- Opportunity cost: what you give up by choosing one job over another.

- Bundling: sometimes delivering two jobs together is cheaper than doing them separately (think: two packages headed in the same direction).

- Modeling opponents: guessing what competitors will bid and how they plan.

- The agents:

- 17 human-coded agents: 12 were built by students in an advanced class (before popular LLMs existed), and 5 simple baseline agents made by researchers.

- 40 LLM-coded agents: The authors used popular LLMs and five prompting styles (including vibe coding) to generate agents. Each LLM/prompt combination was tried twice.

- The tournament:

- 12 double all-play-all tournaments across 4 maps (Switzerland, France, Great Britain, Netherlands).

- About 40,000 matches in total.

- In each match, agents bid on 50 jobs and then plan routes with two vehicles.

- Agents had limited time to bid and plan—just like real life, they couldn’t think forever.

- Important notes about difficulty:

- Planning routes well is “NP-hard,” which means there’s no quick, guaranteed-best solution as the problem gets bigger. You need smart shortcuts and good heuristics (rules of thumb).

- The best solution isn’t just writing code that runs—it’s writing code that reasons well under pressure, competes effectively, and makes profit.

What they found and why it matters

Here are the main results:

- Human-coded agents dominated. The top 5 spots consistently went to student-built agents, not LLM-built ones.

- Most LLM agents lost to very simple baselines. 33 out of 40 LLM-coded agents were beaten by straightforward strategies like “bid your expected cost.”

- Trying to improve a great human solution with an LLM often made it worse. When the authors gave the winning student’s agent to the best-performing LLM and asked it to improve the code, the agent’s rank dropped to 10th place.

- LLMs mostly produced code that ran but didn’t think strategically enough. They struggled with deeper reasoning: planning across many jobs, modeling opponents, and balancing future opportunities.

Why this is important:

- Many current coding benchmarks check if code passes unit tests. That’s a useful skill, but real software problems often require planning, strategy, and optimization. This benchmark shows a gap between “code that runs” and “code that wins.”

- It highlights that vibe coding can be great for quick prototypes, but may fall short in competitive, reasoning-heavy tasks.

What this means for the future

- We need better benchmarks for AI coding—tests that measure strategic thinking, optimization, and multi-agent competition, not just correctness.

- LLMs are powerful tools, but they still struggle with deep planning under uncertainty and competitive strategy. Developers should be cautious when using vibe coding for complex, real-world problems.

- This research encourages building AI that can reason, plan, and learn in dynamic environments—skills needed for truly robust, real-world software.

In short: Passing unit tests isn’t the same as winning in the real world. Today, graduate students still have the edge in complex, strategy-heavy coding—so the next step for AI is learning to think and plan, not just to type.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following points summarize what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper and can guide future research.

- Benchmark scope and realism

- The APDP setup fixes key parameters (e.g., exactly two vehicles per company, 50 tasks per match, undirected graphs, uniform task distribution, reverse first-price sealed-bid auctions) without sensitivity analysis; it is unclear how results change with different fleet sizes, task counts, graph structures, non-uniform/seasonal demand, or alternative market mechanisms.

- Real-world logistics constraints (e.g., time windows, service-level agreements, driver shifts, travel-time asymmetry, stochastic travel times, depot constraints, cancellations) are not modeled; the benchmark’s conclusions may not generalize to richer operational regimes.

- The information structure (observing opponents’ bids each round) is fixed; impacts of alternative auction formats (second-price, VCG, multi-round, bundle auctions, posted pricing, non-revealed bids) remain unexplored.

- Evaluation design and analysis

- Performance is reported as tournament win/loss counts and win rates, but there are no hypothesis tests, confidence intervals, or effect sizes; statistical robustness across seeds and runs is not established.

- Randomization control (e.g., fixed seeds, per-match task distributions) and fairness guarantees (beyond company swaps) are not fully specified; reproducibility of exact match outcomes remains uncertain.

- The paper does not decompose agent performance into auction-stage vs routing-stage contributions; it is unclear whether LLM agents fail primarily at bidding strategy, vehicle routing, or both.

- No scaling curves are provided (e.g., performance vs. number of tasks, vehicles, or time budgets); the computational trade-offs and scalability of LLM-coded agents are not characterized.

- Baselines and comparators

- Human-coded agents are drawn from graduate students (not professionals), selected in part via single-elimination results; this may bias the comparison and limits claims about professional-level coding or broader human performance distributions.

- Effort asymmetry is unaddressed: students had 2–3 weeks of development time, whereas LLM-coded agents were primarily generated via prompting; the effect of equalizing time/effort or allowing extended LLM iteration is unknown.

- Only simple baseline agents are included; stronger classical optimization baselines (e.g., ILP/MILP, CP-SAT/OR-Tools, advanced metaheuristics) are not systematically evaluated against LLM-coded agents.

- LLM setup and prompting methodology

- The paper evaluates four LLMs and five prompting strategies with only two samples per combination; the effect of larger sampling (n-best generation, diversified decoding, code ensembles) and selection mechanisms on final performance is not tested.

- Tool-augmented generation (retrieval of documentation, code search, API calling, solver integration, program synthesis with test generation) is largely absent; the gains from tool use vs pure “vibe coding” are an open question.

- Multi-agent or agentic LLM workflows (planner–critic–executor loops, program repair with tests, instrumentation/logging, chain-of-thought with code-level reasoning traces) are not systematically explored.

- The suggestion to include debug prints or richer telemetry is mentioned but not evaluated; the impact of instrumented self-play feedback on program improvement remains untested.

- Language choice is restricted to Java; the impact of language-specific LLM strengths/weaknesses (e.g., Python with OR-Tools, C++ for performance) on APDP performance is unknown.

- Optimization libraries and integration

- It is unclear whether use of external optimization libraries (e.g., OR-Tools, MILP solvers, VRP heuristics) was permitted or utilized; the performance delta between “from-scratch LLM code” and “LLM code that orchestrates strong solvers” is unmeasured.

- Hybrid approaches (LLM for strategy and decomposition, classical solvers for subproblems) are not benchmarked; the potential of solver-backed LLM agents is an open avenue.

- Opponent modeling and strategic behavior

- Opponent modeling is limited in baselines (e.g., shadow fleets with proxy specs); principled Bayesian models, belief updates, and learning opponents’ cost structures are not systematically assessed.

- Strategic behaviors beyond price shading (e.g., signaling, bluffing, loss-leading bundles, state manipulation, collusion detection/prevention) are not explored; LLM capabilities for multi-agent strategic reasoning under different rules remain unclear.

- Learning and adaptation

- Agents do not learn online or adapt across matches; the potential gains from online learning, self-play training, or RL fine-tuning on APDP are unknown.

- The attempted “LLM improvement of the winning human solution” is a single instance; structured code-improvement regimes (test suites, formal constraints, ablations, iterative tournaments) are not evaluated.

- Failure analysis and quality metrics

- Semantic bug rates and categories (timeouts, missed deliveries, capacity violations) are reported qualitatively; a quantitative taxonomy and root-cause analysis are missing.

- The paper does not separate correctness metrics (constraint adherence) from performance metrics (profit); understanding whether LLM agents primarily fail due to feasibility vs suboptimality is unresolved.

- Code quality attributes (readability, maintainability, modularity, complexity, and runtime efficiency) are not measured; their relationship to competitive performance is unknown.

- Reproducibility and contamination

- Exact LLM versions, configurations, and API settings are not fully specified; paywalled models and evolving releases hinder reproducibility.

- Potential data contamination (training on similar coursework or the Logist platform) is assumed low but not empirically checked; contamination risks and mitigation strategies (e.g., holdout variants) are not detailed.

- Full release status of prompts, seeds, and tournament artifacts is not documented in the main text; turnkey replication requirements (compute, environment, licenses) remain unclear.

- Mechanism design and market realism

- The benchmark uses a reverse first-price sealed-bid mechanism; the impact of alternative market designs, bundle auctions, multi-task contracts, and dynamic truthful mechanisms is not evaluated.

- Profit metrics treat revenue minus distance-based cost; richer economics (risk-adjusted profit, variance, penalties, service-level violations, dynamic fuel/pricing) are not considered.

- Heterogeneity (vehicle costs, capacities, starting locations) is fixed per match; systematic exploration of heterogeneity’s impact on strategy and outcomes is missing.

- External validity and adoption

- Transferability to industrial-scale logistics (e.g., Amazon, FedEx) is not validated; bridging experiments with production-grade datasets and constraints are needed.

- Benchmark adoption/integration plans (licensing, datasets, baselines, documentation, CI/CD, standard metrics) are not fully specified; community standardization and leaderboards are absent.

These gaps point to concrete follow-ups: sensitivity studies across environment parameters and auction formats, decomposition and scaling analyses, stronger solver-backed baselines, tool-augmented LLM workflows, principled opponent modeling and online learning, quantitative failure taxonomies, contamination checks, and industrial-grade validations.

Glossary

- Auction, Pickup, and Delivery Problem (APDP): A market-driven variant of PDP that couples auctions with route planning under capacity constraints; agents bid strategically and plan deliveries to maximize profit. "The Auction, Pickup, and Delivery Problem (APDP) is an open ended problem, one that does not admit a closed-form solution (due to real-time constraints for bidding and planning, bounded rationality, etc.)."

- APPS: A benchmark of programming problems used to evaluate code generation capabilities of models. "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- BigCodeBench: A large-scale benchmark suite for evaluating LLMs on code generation tasks. "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- bounded rationality: The notion that agents have limited time, information, or computational resources, so they cannot perfectly optimize. "In general, heterogeneity in bounded rationality among agents gives rise to many possible strategies."

- CodeBLEU: A code-specific evaluation metric that extends BLEU with program syntax and semantics. "functional correctness~\cite{chen2021evaluating} (with metrics such as pass@k~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, pass-ratio@n~\cite{yeo2024framework}, CodeBLEU~\cite{ren2020codebleu}, etc.)"

- combinatorial auctions: Auctions in which bidders place bids on bundles of items to capture complementarities. "(similar to bidding for bundles in combinatorial auctions)."

- combinatorial optimization: Optimization over discrete structures (e.g., graphs, sets) often with complex constraints. "The Pickup and Delivery Problem (PDP) is part of a broad and significant class of combinatorial optimization problems central to logistics, transportation, and supply chain management~\cite{berbeglia2007static,CAI2023126631}"

- constraint optimization: Optimizing an objective while satisfying hard constraints (e.g., capacity, precedence). "APDP incorporates challenges from non-cooperative MAS (in stage 1, as they compete against other strategic agents), cooperative MAS (in stage 2, as they collaborative manage a fleet of vehicles), auctions under uncertainty (as they do not know exact valuations or future bundles), and constraint optimization."

- constraint satisfaction problem: A formal framework where variables are assigned values to satisfy all given constraints. "Then the prompt describes in detail the vehicle planning problem formulated as a constraint satisfaction problem, using \LaTeX ~to describe variables, constraints, and the cost function."

- data contamination: Leakage of test benchmark content into model training data, invalidating fair evaluation. "they come with a different set of limitations: data contamination (where models train on test data)~\cite{roberts2023cutoff}, limited scope that doesn't reflect real-world and open-ended tasks, lack of adaptability and creative testing, etc."

- dial-a-ride: A transportation routing problem where vehicles pick up and drop off passengers on demand. "PDPs are ubiquitous in real-life outside the described package delivery scenario, in domains such as ride-pooling (dial-a-ride)~\cite{Danassis2022}, meal delivery routing~\cite{reyes2018meal}, supply-chain management for manufacturing companies such as Huawei and Tesla~\cite{CAI2023126631}."

- double all-play-all tournaments: A round-robin format where each agent plays every other agent twice, swapping roles or conditions. "Our results over 12 double all-play-all tournaments and k matches demonstrate (i) a clear superiority of human(graduate students)-coded agents..."

- economies of scope: Cost advantages from delivering multiple tasks together, reducing total cost relative to separate deliveries. "we can combine multiple pickups (economies of scope)."

- heterogeneous fleet of vehicles: A set of vehicles with differing capacities, costs, and starting locations. "I.e., the agents manage a heterogeneous set of companies, each operating a heterogeneous fleet of vehicles."

- HumanEval: A widely used benchmark of Python function synthesis tasks for evaluating code generation. "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- LiveCodeBench: A benchmark focusing on evaluating models on coding tasks with executable checks. "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- marginal cost: The additional cost incurred by adding one more task to the current plan or schedule. "A competitive bid depends on (i) the marginal cost of adding the auctioned task to the partial delivery plan, given the already won tasks, (ii) the marginal cost of the opponent, and (iii) other strategic decisions..."

- MBBP: A benchmark of programming problems used to assess code generation (note: appears as “MBBP” in the paper’s benchmark list). "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- Multi-agent systems (MAS): Systems with multiple interacting agents that may cooperate or compete. "APDP incorporates challenges from non-cooperative MAS (in stage 1, as they compete against other strategic agents), cooperative MAS (in stage 2, as they collaborative manage a fleet of vehicles), auctions under uncertainty..."

- NP-hard: A complexity class indicating that no known polynomial-time algorithm exists to solve all instances optimally. "The Pickup and Delivery Problem (PDP) is NP-hard~\cite{CAI2023126631}."

- opportunity cost: The forgone value of the best alternative when choosing a particular action. "A rational agent must consider both the marginal cost (the additional cost incurred to service a new task), and the opportunity cost (the expected value of the best alternative task that is foregone, i.e., potential loss of profit) of its actions."

- pass@k: Metric estimating the chance that at least one of k generated solutions passes unit tests. "functional correctness~\cite{chen2021evaluating} (with metrics such as pass@k~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, pass-ratio@n~\cite{yeo2024framework}, CodeBLEU~\cite{ren2020codebleu}, etc.)"

- pass-ratio@n: Metric measuring the proportion of valid solutions across n attempts. "functional correctness~\cite{chen2021evaluating} (with metrics such as pass@k~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, pass-ratio@n~\cite{yeo2024framework}, CodeBLEU~\cite{ren2020codebleu}, etc.)"

- Pickup and Delivery Problem (PDP): A vehicle routing problem involving picking up items and delivering them under constraints. "The Pickup and Delivery Problem (PDP) is NP-hard~\cite{CAI2023126631}."

- reverse first-price sealed-bid auction: An auction where the lowest bid wins and the winner is paid its bid, with bids submitted privately. "Tasks are sold via a reverse first-price sealed-bid auction, i.e., a company's bid corresponds to the amount of money they want to be paid to deliver the task."

- sequential decision-making under uncertainty: Planning a sequence of actions while future states, tasks, or opponents’ behavior are not fully known. "These multifaceted challenges -- combinatorial optimization, sequential decision-making under uncertainty, and strategic interactions -- make APDP a challenging benchmark for the next frontier of code generation."

- shadow fleet: A simulated or proxy fleet used to estimate an opponent’s costs and behavior. "For the opponents marginal cost calculation, it keeps track of the opponent's won tasks and simulates a shadow fleet using its own fleet specs as a proxy."

- single-elimination tournament: Competition format where a single loss eliminates a participant. "which then competed in a single-elimination tournament for extra course credits."

- Stochastic Local Search: A heuristic optimization method that explores the solution space using randomness and local moves. "You do not have to implement Stochastic Local Search for the delivery planning."

- subadditive: A property where the combined cost of tasks is less than or equal to the sum of individual costs. "The cost of serving a set of tasks is typically subadditive; i.e., the cost of serving tasks A and B together may be less than the cost of serving A plus the cost of serving B."

- SWEBench: A benchmark suite for software engineering tasks, often used to evaluate LLMs on bug fixing and PR tasks. "Some representative and most commonly used~\cite{achiam2023gpt,anthropicreport,gemini25report} benchmarks are: HumanEval~\cite{chen2021evaluating}, APPS~\cite{hendrycks2measuring}, MBBP~\cite{austin2021program}, BigCodeBench\cite{zhuobigcodebench}, LiveCodeBench~\cite{jainlivecodebench, whitelivebench}, SWEBench and its variants~\cite{jimenezswe,swebenchv,zhang2025swe, swelong, miserendino2025swe}, Aider Polyglot\cite{aider}, WebDev Arena~\cite{chiang2024chatbot,lmarena}, etc."

- vehicle routing: The task of planning routes for a fleet to serve all assignments while meeting constraints. "In the second stage (vehicle routing), each agent has to solve a static PDP problem, efficiently scheduling a fleet of vehicles of different characteristics..."

- Vibe-coding: A colloquial approach where users rely on LLMs to generate code directly from natural language prompts. "`Vibe-coding' has empowered users of all technical backgrounds to turn their ideas into code in seconds~\cite{martin_vibe_2025}."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items can be implemented with the paper’s open-sourced APDP benchmark and current organizational practices to yield value now.

- APDP-based evaluation suite for AI code assistants

- Sector: Software/AI, MLOps

- Action: Integrate the benchmark into model evaluation pipelines to test LLM-generated code on strategic planning, optimization, and multi-agent competition, not just unit tests.

- Tools/workflows: Double all-play-all tournaments across multiple network topologies, self-play, opponent modeling, win-rate and profit metrics; scenario-based semantic checks (capacity/precedence/pickup-delivery).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Java environment, Logist platform availability; compute for simulations; access to multiple LLMs; internal CI/CD hooks to run tournaments.

- Guardrails for vibe coding in engineering teams

- Sector: Software engineering

- Action: Update engineering guidelines to caution against relying solely on vibe coding for complex optimization or competitive strategy, mandating human algorithm design and semantic reviews.

- Tools/workflows: “LLM bootstrap + human optimization” workflow; semantic test suites; explicit timeouts and capacity constraint checks; adversarial scenario tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Team training in auctions/optimization; ability to author semantic test harnesses.

- Logistics strategy prototyping sandbox

- Sector: Logistics, transportation

- Action: Use APDP as a “digital twin” to prototype bidding and routing heuristics under reverse first-price auctions, test underbidding schedules, opponent modeling, and bundle valuation strategies.

- Tools/workflows: Baseline strategies (Honest, ModelOpponent, RiskSeeking) as starting points; insertion heuristics and local search planners; profit vs. risk trade-off dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mapping from APDP abstractions to firm-specific constraints (vehicle heterogeneity, costs); synthetic task distributions approximating real lanes.

- Curriculum modules and competitions in multi-agent planning

- Sector: Academia/education

- Action: Adopt the APDP benchmark in graduate/upper-division courses on multi-agent systems, auctions, and combinatorial optimization; run student tournaments to teach strategic coding.

- Tools/workflows: Project briefs mirroring A1 prompt content; guided labs on vehicle routing, auction theory, and opponent modeling; grading via win-rate/profit and code quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Java proficiency; faculty familiar with MAS and PDP; campus compute resources.

- Procurement and market-ops training on auction risks

- Sector: Public procurement, marketplaces

- Action: Train staff using simulations to understand how automated agents may behave in reverse auctions (e.g., underbidding early to gain positional advantage) and where naive automation fails.

- Tools/workflows: Scenario libraries showing strategic missteps and their downstream costs; policy playbooks for bid audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Mapping APDP to the agency’s auction format; legal constraints on simulated training data.

- Semantic QA expansion beyond unit tests

- Sector: Software quality assurance

- Action: Augment test suites with performance-based and constraint-validity checks (e.g., pickup-before-delivery, capacity non-violation, time-limit adherence) for code generated by LLMs.

- Tools/workflows: Scenario generators; violation detectors; “semantic diff” reports comparing functional correctness to strategic efficacy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of domain-specific constraints to encode; culture of performance-oriented testing.

- Prompt design playbooks for complex optimization tasks

- Sector: Software/AI

- Action: Use structured prompts that include constraints, objectives, time limits, and strategy components; pair with iterative sampling and self-play evaluation to select the best candidate.

- Tools/workflows: Prompt templates akin to Author Prompt #1; multi-sample generation; automatic tournament selection of best agent; LLM-as-critic only for code review, not unconditional acceptance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to multiple LLMs; tolerance for iterative sampling costs; organizational discipline to reject degraded “improvements.”

- Benchmarking human vs. LLM coding for hiring and upskilling

- Sector: HR/technical hiring, L&D

- Action: Use APDP tasks to assess candidates’ ability to design algorithms, handle constraints, and reason strategically; incorporate as an advanced coding challenge for senior roles.

- Tools/workflows: Timed auctions + planning tasks; analysis of marginal/opportunity cost reasoning; opponent modeling exercises.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal and fairness considerations in candidate assessment; clear rubrics beyond win-rate.

- Research data generation for strategy analysis

- Sector: Academia/industry R&D

- Action: Generate large datasets of matches, bids, and plans to paper bounded rationality, dynamic auctions, and learning in competitive environments; publish baselines and ablations.

- Tools/workflows: Automated tournament runners; logging schemas for bids/routes; statistical analyses of strategy performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data management and reproducibility practices; IRB considerations where applicable.

Long-Term Applications

The following items require further research, scaling, reliability improvements, or domain integration before widespread deployment.

- Hybrid code-generation systems with embedded optimization

- Sector: Software/AI

- Vision: Combine LLMs with formal solvers (MILP/CP), heuristic libraries, and verified constraint modules to produce code that is competitive on planning and auctions.

- Potential products: Neuro-symbolic coding assistants; solver-backed agent SDKs; “strategy-aware” codegen IDE plugins.

- Dependencies: Stable solver integrations; robust interfaces for constraints/objectives; evidence of improved semantic reliability over pure LLMs.

- Autonomous bidding agents for freight marketplaces

- Sector: Logistics, supply chain

- Vision: Deploy agents that jointly optimize bids and multi-vehicle routing in live markets (e.g., load boards), accounting for bundle synergies, risk, and competition.

- Potential products: Carrier-side bidding copilots; TMS plugins that simulate future lanes and commit strategies.

- Dependencies: Real-time data feeds; compliance with market rules; safety and auditability; performance guarantees under uncertainty.

- Multi-robot pickup and delivery under auctions

- Sector: Robotics, warehousing

- Vision: Apply APDP-like auction and routing patterns to allocate tasks among heterogeneous robot fleets, optimizing throughput and energy.

- Potential products: Warehouse orchestration systems; auction-based task allocators for AMRs.

- Dependencies: High-fidelity simulators; integration with robot controllers; safety certification.

- Bidding strategy agents in energy and ad markets

- Sector: Energy, advertising, finance

- Vision: Generalize benchmark to multi-agent market settings (e.g., electricity day-ahead auctions, ad exchanges), enabling robust AI bidders with opponent modeling and dynamic risk schedules.

- Potential products: Market simulation suites; “trustworthy bidding” toolkits; compliance-friendly algorithmic traders.

- Dependencies: Domain-specific constraints (capacity, ramp limits, budget pacing); regulatory oversight and audit trails.

- Industry standards for evaluating AI code generation beyond unit tests

- Sector: Standards/policy

- Vision: Establish simulation-based benchmarks (like APDP) as required evaluations for AI coding tools in safety- or mission-critical domains.

- Potential products: Certification programs; conformance tests; third-party audit services.

- Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; reproducible benchmark governance; addressing data contamination concerns.

- Formal verification and runtime monitoring of strategy constraints

- Sector: Software safety, critical systems

- Vision: Pair LLM-generated code with formal guarantees of capacity/precedence/time-limit compliance; monitor strategic performance and constraint adherence in production.

- Potential products: Constraint verifiers; runtime monitors; “fail-safe” planners that repair invalid schedules.

- Dependencies: Scalable verification for complex planners; interpretable guarantees acceptable to regulators.

- Curriculum, credentials, and best-practice guides for vibe coding

- Sector: Education/professional certification

- Vision: Standardize training that teaches when and how to use LLMs for coding, emphasizing semantic pitfalls, strategic tasks, and human-in-the-loop design.

- Potential products: Microcredentials; courseware aligned to APDP; industry-aligned capstones.

- Dependencies: Broad adoption by universities and enterprises; continuous updates as LLM capabilities evolve.

- Consumer-grade optimization app builders with safety rails

- Sector: Daily life/SMB software

- Vision: Low-code tools for small businesses to build delivery/dispatch apps with embedded constraint checks and simulation-backed validation of LLM-generated logic.

- Potential products: “Route & Bid Wizard” with sandbox simulations; template packs for common tasks (dial-a-ride, meal delivery).

- Dependencies: Simplified UIs; robust defaults; high-quality templates; user education on limits of automation.

- Benchmark expansion to richer real-world constraints

- Sector: Logistics, operations research

- Vision: Extend APDP to time windows, stochastic travel times, multi-depot, driver regulations, and partial observability to better reflect industry.

- Potential products: Advanced benchmark suites; sector-specific variants (last-mile, line-haul).

- Dependencies: Modeling fidelity; performance metrics beyond profit (service level, SLA adherence).

- Evidence-based regulation on automated market participation

- Sector: Policy/regulation

- Vision: Use findings (e.g., naive agents degrade performance; strategic behavior emerges) to inform rules on automated participants in auctions and marketplaces.

- Potential products: Participation standards; transparency and audit requirements; sandboxes for algorithmic market testing.

- Dependencies: Regulatory capacity; coordination with market operators; risk assessments for manipulation or instability.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.