P1: Mastering Physics Olympiads with Reinforcement Learning (2511.13612v1)

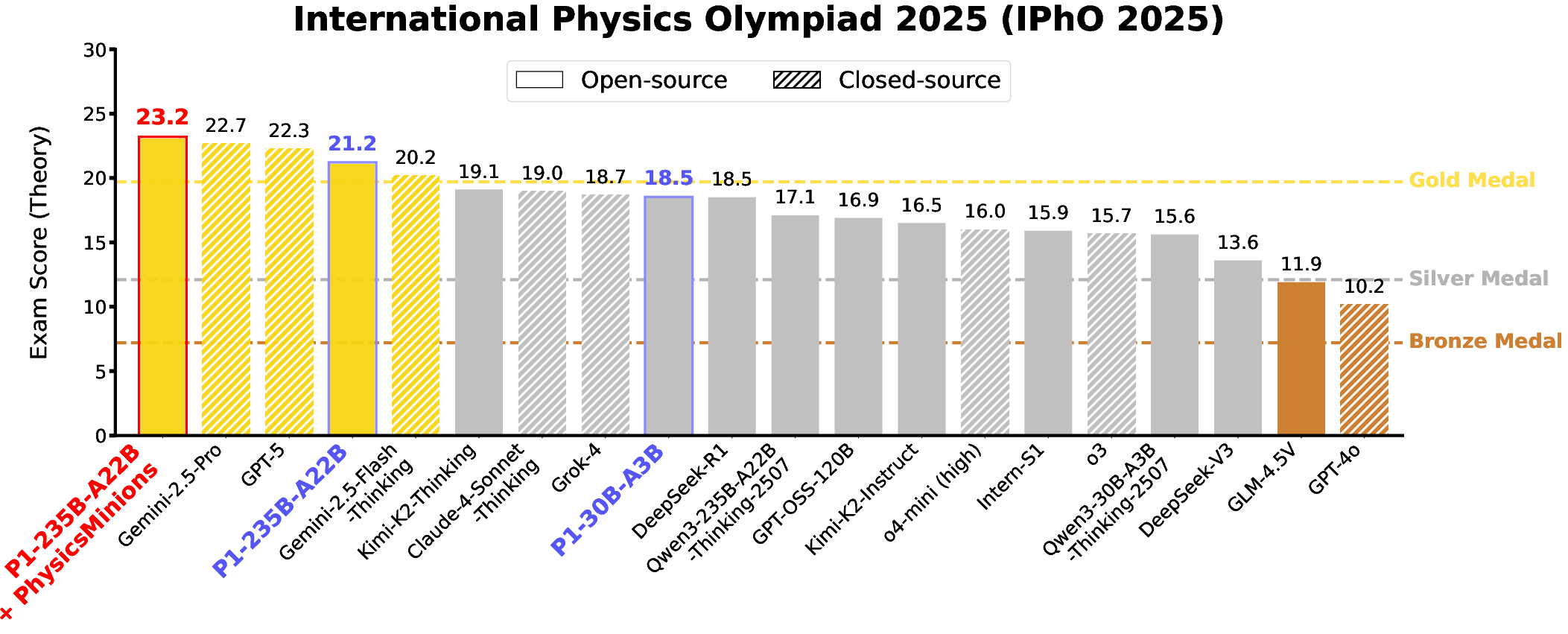

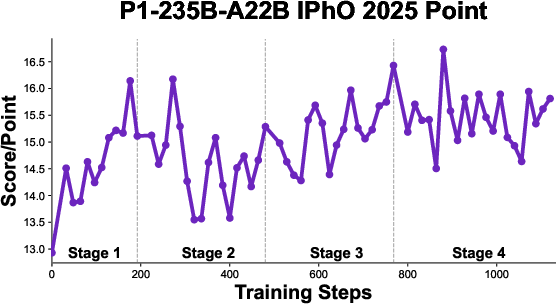

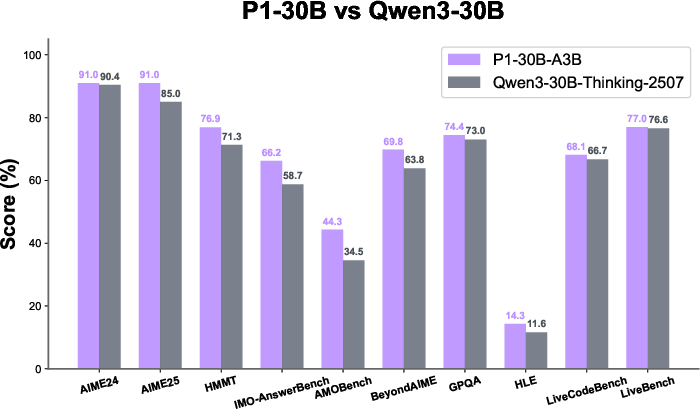

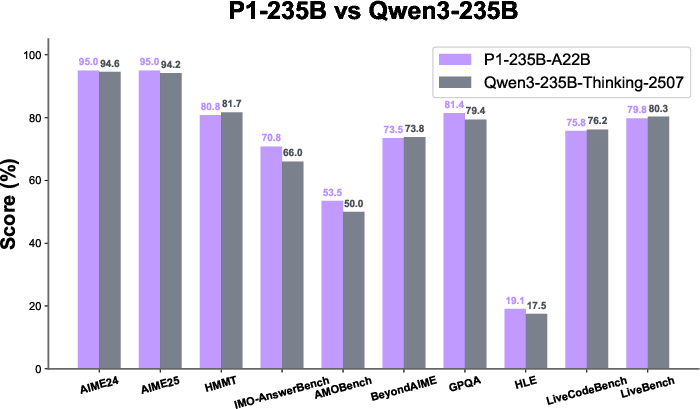

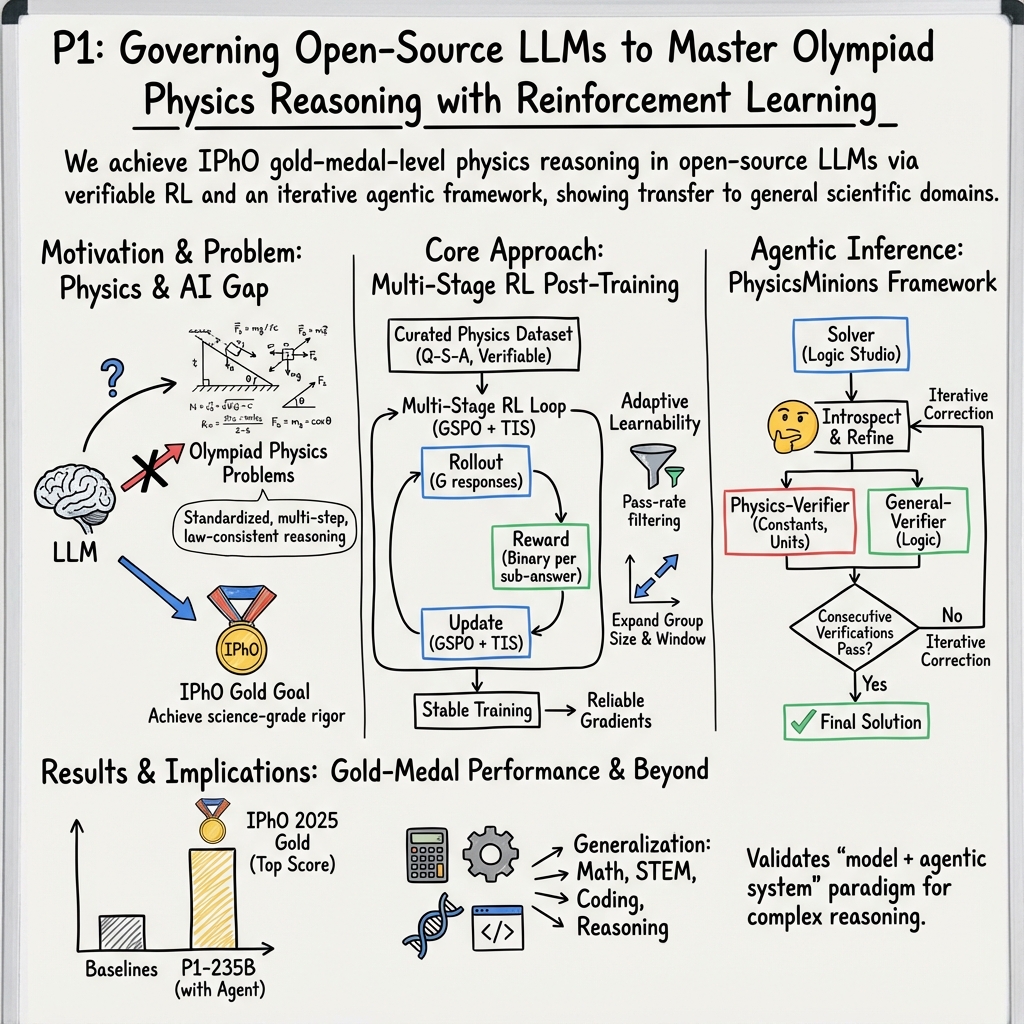

Abstract: Recent progress in LLMs has moved the frontier from puzzle-solving to science-grade reasoning-the kind needed to tackle problems whose answers must stand against nature, not merely fit a rubric. Physics is the sharpest test of this shift, which binds symbols to reality in a fundamental way, serving as the cornerstone of most modern technologies. In this work, we manage to advance physics research by developing LLMs with exceptional physics reasoning capabilities, especially excel at solving Olympiad-level physics problems. We introduce P1, a family of open-source physics reasoning models trained entirely through reinforcement learning (RL). Among them, P1-235B-A22B is the first open-source model with Gold-medal performance at the latest International Physics Olympiad (IPhO 2025), and wins 12 gold medals out of 13 international/regional physics competitions in 2024/2025. P1-30B-A3B also surpasses almost all other open-source models on IPhO 2025, getting a silver medal. Further equipped with an agentic framework PhysicsMinions, P1-235B-A22B+PhysicsMinions achieves overall No.1 on IPhO 2025, and obtains the highest average score over the 13 physics competitions. Besides physics, P1 models also present great performance on other reasoning tasks like math and coding, showing the great generalibility of P1 series.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

P1: Mastering Physics Olympiads with Reinforcement Learning — explained for a 14-year-old

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces P1, a family of smart AI models designed to solve tough physics problems like those in the International Physics Olympiad (IPhO). The main idea is that the models don’t just memorize facts; they learn how to reason step by step like a scientist. The team trained these models using a method called reinforcement learning, and then added an “agent” system that helps the models check and improve their own answers. The result: P1 became the first open-source model to earn a gold-medal level score at IPhO 2025 and won top results in many other competitions.

What questions were the researchers trying to answer?

The paper focuses on a few clear goals:

- Can an AI learn to do “science-grade” reasoning, not just simple math or trivia?

- Can it solve Olympiad-level physics problems that require careful thinking, long solutions, and correct final answers?

- How do we train an AI to keep improving, even when the problems are hard and the feedback (right/wrong) is simple?

- Can skills learned in physics also help with other subjects like math and coding?

How did they train the AI? (Explained with simple ideas)

Think of the AI as a very advanced student that:

- Practices on a large set of physics problems with solutions.

- Tries different ways to solve each problem.

- Gets a “reward” when the final answer is correct.

- Learns which kinds of reasoning steps lead to correct results more often.

Here are the main parts of their approach, in everyday language:

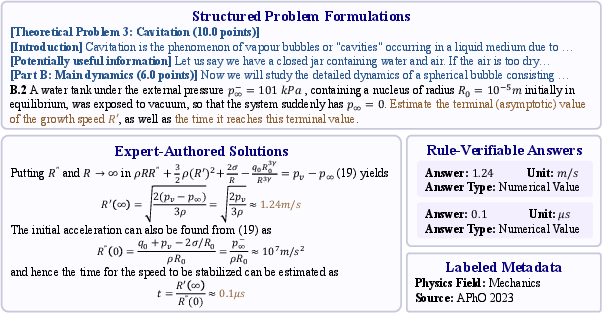

- Physics problem set: They built a dataset of 5,065 challenging physics problems, mostly from Olympiads. Each problem includes:

- The full question.

- An expert-written solution showing the steps.

- A clear final answer that can be checked automatically (like the correct number or formula).

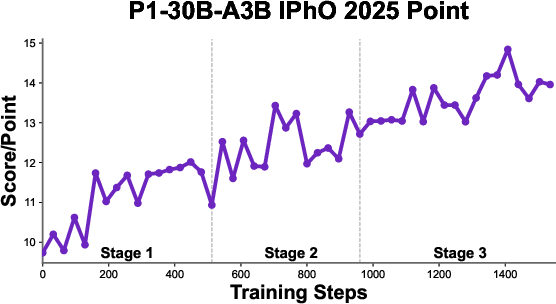

- Reinforcement learning (RL): This is like practice with a coach. The model tries to solve a problem, and if its final answer matches the correct one, it gets a point. If not, it gets zero. Over many tries, it learns which approaches work.

- Group practice: Instead of making one attempt per problem, the model makes many attempts and compares them. Learning from a group of attempts helps it figure out what works best and improves faster.

- Answer formatting: The model is told to put each final answer in a separate “box” like this:

\boxed{...}. This makes it easy to extract and check each part of the answer, especially when a problem asks for more than one thing. - Automatic checking (verifiers): Imagine two kinds of judges:

- A rule-based judge that uses math tools (like a smart calculator) to check if two formulas are equivalent or if a number is right.

- A model-based judge that reads the problem and both answers and says “correct” or “incorrect” when the math is too tricky for rules alone. During training, they stick to the rule-based judge; the model-based judge helps during evaluation.

- Keeping the learning strong:

- Filter out problems that are too easy (to avoid the model getting lazy) or impossible (to avoid frustration). This keeps training focused on problems that are challenging but solvable.

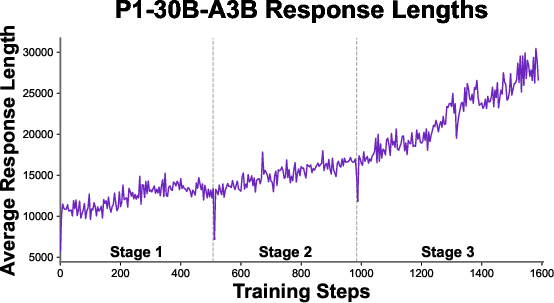

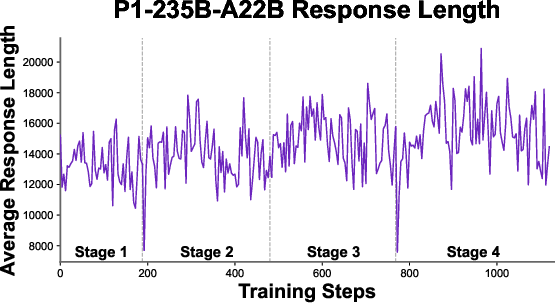

- Let the model write longer solutions over time. Complex physics often needs more steps; they gradually increased how much the model could write so it could think more deeply.

- Increase the number of attempts per problem as the model gets better, to give it more chances to find a correct path for hard problems.

- Stable training: The model uses different computer systems for practicing and for updating its knowledge. Those systems don’t always behave identically, which can cause instability. To fix this, the team adjusted the learning math so it stays fair even when the systems differ—like adjusting scores when two stopwatches measure slightly differently.

- Test-time “agent” system (PhysicsMinions): During actual problem solving, they used a mini team of AI helpers:

- A solver that writes the solution.

- Verifiers that check physics consistency (like units) and logic.

- If checks fail, the solver revises the solution and tries again, until it passes multiple checks in a row. For these P1 models, the picture-reading part was turned off (they worked on text-only problems).

What did they find?

The results were impressive:

- P1-235B-A22B (the largest P1 model) reached gold-medal level at IPhO 2025, the first time an open-source model achieved this. Across 13 recent physics competitions, it earned 12 golds and 1 silver.

- When combined with the PhysicsMinions agent system, P1-235B-A22B ranked No. 1 overall on IPhO 2025 and had the highest average score across all 13 competitions.

- Even the smaller P1-30B-A3B model performed very well, earning a silver at IPhO 2025 and beating most other open-source models.

- The training didn’t only help with physics. The P1 models also improved in math and coding tasks, showing that learning to reason well in physics can transfer to other subjects.

Why this matters: Physics problems are a tough test of real reasoning because they demand understanding, careful step-by-step thinking, and answers that must match the laws of nature. Doing well here suggests the AI has learned deeper thinking, not just memorization.

What’s the impact?

This work points toward AI that can reason more like scientists:

- It shows that open-source models can reach elite levels in complex problem solving, not just closed, private systems.

- Students and teachers might use such models to paper, check solutions, and learn how to reason through hard problems step by step.

- Researchers could build on this open ecosystem—models, training methods, datasets, and agents—to push AI toward helping with real scientific discovery.

- Since the skills transfer to math and coding, this approach could help build general-purpose reasoning assistants that are useful across many subjects.

In short, P1 demonstrates that with the right training and smart checking at test time, AI can tackle Olympiad-level physics and may become a powerful partner in learning and science.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each point is phrased to be directly actionable for future research.

- Data contamination risks remain unquantified: no analysis ensures the HiPhO 2024–2025 test set is fully unseen by the base models’ pretraining corpora or other external training sources; a thorough decontamination audit is needed.

- Evaluation scope is limited to theoretical, text-only problems: tasks requiring diagrams, experimental design, or practical measurements were removed; the approach’s effectiveness on multimodal, lab-style, or real-world physics problems is unknown.

- Translation reliability is not evaluated: Chinese-to-English normalization was done with an LLM (Claude), but there is no measurement of semantic drift, translation error rates, or their impact on training and evaluation.

- Dataset curation biases learning toward mid-difficulty: preliminary pass-rate filtering removes tasks with pass=0 and pass>0.7 (based on a 30B model), potentially excluding genuinely hard/novel problems and biasing training distribution; curriculum or adaptive inclusion strategies for hard tasks remain unexplored.

- No subfield-level performance analysis: although the dataset spans 5 fields and 25 subfields, the paper does not report per-subfield accuracy, transfer across subfields, or failure patterns (e.g., electromagnetism vs. mechanics vs. thermodynamics).

- Reward design is coarse and may be gamed: the binary “Correct-or-Not” reward averaged across sub-answers overlooks step-wise reasoning quality, unit correctness, dimensional consistency, and error tolerance; step-level or physics-aware reward shaping is missing.

- Units and dimensional analysis are underutilized at train time: despite unit metadata, units are excluded from the final boxed answers and do not appear in the training reward; integrating unit checks, dimensional consistency, and physically plausible constraints into RL is an open direction.

- Verifier limitations are not rigorously characterized: rule-based symbolic checks (SymPy/math-verify) and model-based verification (Qwen3-30B-Instruct) have unknown false-positive/false-negative rates and failure modes (e.g., algebraic equivalence masking physical errors); a calibrated verifier benchmark is needed.

- Potential verifier bias and “self-judging” risk: using an LLM from the same family (Qwen) to judge answers may bias validation; cross-family, blinded verifiers and human audits could reduce bias.

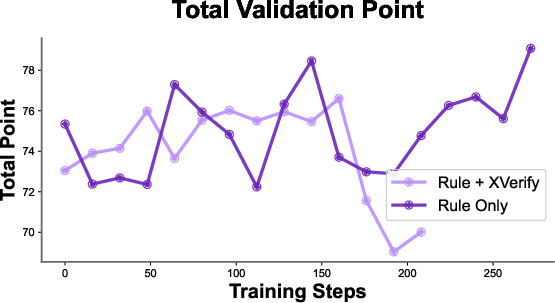

- Missing explanation of verifier choices: the paper references a Section on model-based verification rationale (Section “xverify”), but it is not present; why model-based verifiers are disabled during training and how this affects learning remains unexplained.

- Lack of ablation studies on key algorithmic components: there is no quantitative isolation of contributions from GSPO vs. PPO/GRPO, TIS vs. no-TIS, group size scaling, generation window scaling, and preliminary pass-rate filtering; component-wise and combined ablations are needed.

- Train–inference mismatch mitigation (TIS) impact is unmeasured: TIS is adopted but its effect on stability, variance, and final scores vs. baselines is not reported; sensitivity to the truncation parameter C and clipping epsilon remains unknown.

- Scaling laws and compute-efficiency are unreported: training time, GPU-hours, memory footprint, batch sizes per step, sampling temperature/top-p, and throughput are not provided; reproducibility and cost–accuracy trade-offs need documentation.

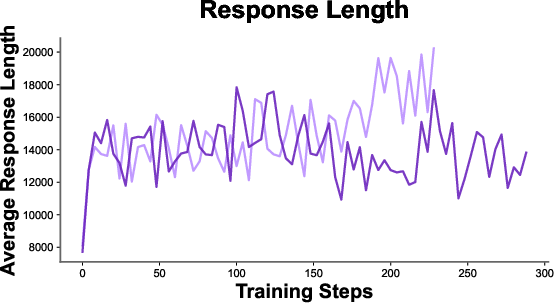

- Long-context utilization needs analysis: generation windows up to 80k tokens are used, but the correlation between response length and accuracy, truncation rates, verbosity vs. precision, and diminishing returns are not studied.

- Test-time agentic augmentation fairness is unclear: only P1 is paired with PhysicsMinions; applying comparable agent frameworks to other models and reporting improvements is necessary to disentangle training vs. agent effects.

- Agent hyperparameters and cost are under-specified: PhysicsMinions’ CV parameter, iteration counts, timeouts, wall-clock latency, and compute overhead are not reported for P1; speed–accuracy trade-offs and reliability under budget constraints remain open.

- Generalization beyond Olympiad-style physics is untested: performance on undergraduate/graduate conceptual proofs, open-ended modeling, experimental planning, and research-level problems is unknown.

- Transfer to other domains lacks methodological detail: claims of improved math/coding/general reasoning lack experimental protocols, baselines, and task breakdowns; mechanisms of cross-domain transfer from physics RL are not analyzed.

- Robustness to adversarial or noisy inputs is unexamined: behavior under perturbed statements, misleading units/constants, deceptive prompts, and incomplete problem context is not evaluated.

- Error taxonomy is missing: there is no systematic categorization of failures (modeling mistakes, algebraic slips, unit errors, boundary condition misapplication, misread problem constraints), nor targeted interventions.

- Scoring alignment with human grading is incomplete: averaging sub-answer rewards does not mirror weighted point distributions; the mapping from model-derived scores to medal thresholds is not fully specified or validated against official scoring rubrics.

- Handling of rounding, numerical tolerances, and symbolic forms is under-specified: thresholds for numeric equality, accepted forms for equivalent expressions, and consistent treatment of constants are not detailed, leaving verification ambiguities.

- Base-model dependence is untested: the RL pipeline is only demonstrated on Qwen3 bases (30B and 235B); applicability to other architectures/families (e.g., LLaMA, Mistral, GPT-OSS) and MoE vs. dense models is an open question.

- Data licensing and release details are unclear: explicit licenses, provenance per item, and redistribution policies (especially for Olympiad materials and textbook content) are not described; legal and ethical use guidelines need clarification.

- Subdivision of long problems may alter logical structure: expert restructuring to fit context limits could affect problem difficulty and reasoning paths; the impact of subdivisions on solution quality has not been measured.

- Reward hacking risks are unaddressed: models may learn to emit boxed answers that pass symbolic checks while the reasoning is incorrect or inconsistent; integrating process-based verification or physics constraints could mitigate this.

- Integration with simulation and formal physics tools is absent: there is no use of numerical simulators, dimensional analyzers, or theorem provers to enforce physical validity beyond final-answer equivalence; exploring hybrid verification remains open.

- Inference timeouts and stability are not reported for P1: unlike Kimi-K2-Thinking, P1’s timeout rates, failure-to-complete cases, and robustness across problem lengths are not disclosed.

- Reproducibility artifacts are incomplete: seeds, exact code configurations, checkpoint release status, and detailed training logs/metrics are not provided; a full reproducibility package would enable independent validation.

Glossary

- Adaptive Exploration Space Expansion: A training strategy that progressively broadens the model’s search space (e.g., more samples, longer outputs) to sustain learning as capability grows. "To address this, we dynamically expand the exploration space in line with the modelâs evolving capability, thereby sustaining learnability."

- Adaptive Learnability Adjustment: Techniques that maintain a model’s ability to improve during RL post-training by tuning data difficulty and exploration settings over time. "Adaptive Learnability Adjustment"

- Advantage function: In RL, a function estimating the relative benefit of an action compared to a baseline at a given state. "where is the advantage function estimating the relative value of action in state ."

- Agentic control: An inference-time capability where the model orchestrates reasoning with iterative critique and refinement, like an autonomous agent. "but also deploys it adaptively through agentic control at inference."

- Agentic framework: A structured, multi-component system that enables models to act as agents, coordinating tools and self-verification. "Further equipped with an agentic framework PhysicsMinions, P1-235B-A22B+PhysicsMinions achieves overall No.1 on IPhO 2025, and obtains the highest average score over the 13 physics competitions."

- Answer Extraction: The process of parsing final answers from generated text with a constrained output format for reliable verification. "We design prompts that enforce a multi-box output format, requiring the model to place each sub-answer sequentially inside separate \boxed environments, in order to simplify the answer extraction."

- APhO: Asian Physics Olympiad, a regional high-level physics competition used for benchmarking. "âincluding APhO, IPhO and othersâ"

- Coevolutionary: Refers to interacting processes or components that iteratively refine each other’s outputs in a feedback loop. "PhysicsMinions consists of three coevolutionary studios: the Visual Studio, the Logic Studio, and the Review Studio."

- Correct-or-Not design: A binary reward scheme in RL that gives 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect solutions. "Following the Correct-or-Not design in RLVR methods~\citep{guo2025deepseek-r1,zheng2025gspo}, we employ a binary reward scheme based on answer correctness"

- DrGRPO: A method that integrates symbolic and rule-based checks to verify mathematical expressions during RL. "Inspired by DrGRPO~\citep{liu2025drgrpo}, we combine symbolic computation with rule-based checks using SymPy~\citep{meurer2017sympy} and math-verify~\citep{math-verify} heuristics."

- Entropy collapse: A training failure mode where the model’s output distribution becomes overly deterministic, harming exploration. "effectively mitigates common challenges such as reward sparsity, entropy collapse, and training stagnation."

- Entropy mechanism analysis: A formal paper of how entropy (output uncertainty) affects learning dynamics and exploration in RL. "According to the entropy mechanism analysis~\citep{cui2025entropy}, when the majority of tasks can be solved with high confidence, RL updates push the policy toward low-entropy solutions, accelerating collapse."

- EuPhO: European Physics Olympiad, a continental competition included in the benchmark suite. "span 7 major types: IPhO, APhO, EuPhO, NBPhO, PanPhO, PanMechanics, and F=MA."

- F=MA: A physics contest (named after Newton’s second law) used as part of the evaluation benchmark. "span 7 major types: IPhO, APhO, EuPhO, NBPhO, PanPhO, PanMechanics, and F=MA."

- FSDP: Fully Sharded Data Parallel, a distributed training technique to scale large models. "training (e.g. FSDP~\citep{merry2021fsdp} and Megatron~\citep{shoeybi2019megatron})."

- Generation window: The maximum output length allowed during inference/training that constrains reasoning depth. "The maximum output length (generation window) limits the depth of reasoning that can be expressed."

- Group size expansion: Increasing the number of sampled responses per prompt during RL to enhance learning signals. "Increasing the group size enhances the probability of generating at least one high-quality trajectory"

- GSPO (Group Sequence Policy Optimization): An RL algorithm that optimizes at the sequence level using normalized importance ratios and group-based advantages. "GSPO~\citep{zheng2025gspo} elevates optimization from the token level~\citep{shao2024grpo,yu2025dapo} to the sequence level, employing length-normalized sequence likelihood importance ratios:"

- HiPhO: A benchmark aggregating 13 recent physics Olympiads for standardized evaluation. "evaluate them on HiPhO~\citep{2025hipho}, a new benchmark aggregating the latest 13 Olympiad exams from 2024â2025."

- Importance weighting: A correction technique to adjust gradients when sampling and training policies differ. "which applies importance weighting to rebalance gradients computed under the training policy using trajectories sampled from the rollout policy ."

- International Physics Olympiad (IPhO): The premier global physics competition used to assess scientific reasoning capability. "International Physics Olympiad (IPhO)~\citep{qiu2025physicsagent,physicsminions}"

- length-normalized sequence likelihood importance ratios: A normalization in GSPO to reduce variance across different output lengths. "employing length-normalized sequence likelihood importance ratios:"

- Markov Decision Process (MDP): A formal framework describing states, actions, transitions, and rewards in RL. "Let denote the underlying Markov Decision Process (MDP), where:"

- math-verify: Heuristics and tooling for checking mathematical equivalence and correctness in generated answers. "using SymPy~\citep{meurer2017sympy} and math-verify~\citep{math-verify} heuristics."

- Megatron: A large-scale training system for transformer models. "training (e.g. FSDP~\citep{merry2021fsdp} and Megatron~\citep{shoeybi2019megatron})."

- Model-based verifier: A verifier implemented with an LLM to judge answer correctness beyond rule-based checks. "Model-based verifier (used only in validation)."

- MoE models: Mixture-of-Experts architectures that route tokens to specialized expert networks. "we build up our algorithm upon GSPO to stabilize the training of MoE models."

- NBPhO: Nordic-Baltic Physics Olympiad, a regional competition included in the benchmark. "span 7 major types: IPhO, APhO, EuPhO, NBPhO, PanPhO, PanMechanics, and F=MA."

- OCR: Optical Character Recognition used to convert PDFs to machine-readable text. "Source materials in PDF format are parsed into Markdown using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tools."

- pass@88: A sampling metric indicating success when at least one of 88 generated solutions is correct. "we perform rollouts on the training dataset using the Qwen3-30B-A3B-Thinking model under a pass@88 setting"

- Pass rate filtering: Data pruning based on the model’s preliminary success rates to avoid trivial or impossible samples. "we apply a filtering procedure before training, based on pass rate statistics."

- PhysicsMinions: A multi-agent system for physics reasoning with solver, introspector, and verifiers. "During inference, we combine P1 models with the PhysicsMinions~\citep{physicsminions} agent framework"

- Policy gradient: An RL method that updates model parameters by ascending the expected return gradient. "The policy gradient~\citep{sutton1999pg-sutton} method optimizes by ascending the gradient of the expected return:"

- Reinforcement learning (RL) post-training: Fine-tuning a pretrained LLM with RL to improve reasoning and correctness. "The P1 models are trained purely through RL post-training~\citep{guo2025deepseek-r1,cui2025prime-rl} on top of base LLMs."

- Reward aggregation: Combining correctness over multiple sub-answers into a single scalar reward. "we adopt a test-case-style reward aggregation similar to program evaluation"

- Reward sparsity: A condition where correct signals are infrequent, making learning difficult. "Filtering these tasks mitigates reward sparsity."

- Rollout policy: The policy used to generate trajectories for training evaluation, possibly different from the training policy. "using trajectories sampled from the rollout policy ."

- Rule-based verifier: A symbolic/math-based system for checking equivalence and correctness of generated answers. "Rule-based verifier."

- SGLang: An inference engine used for efficient LLM rollouts. "rollout (e.g. vllm~\citep{kwon2023vllm} and SGLang~\citep{zheng2024sglang})"

- SymPy: A Python library for symbolic mathematics used to verify algebraic expressions. "using SymPy~\citep{meurer2017sympy} and math-verify~\citep{math-verify} heuristics."

- Test-time Scaling: Increasing reasoning effort and iterative verification at inference without additional training. "Test-time Scaling."

- Train-inference Mismatch: Discrepancies between rollout and training engines that bias gradients and destabilize learning. "Recent studies~\citep{yao2025tis,jiacai2025speed} have noticed that the train-inference engine difference is a key cause to instability in training."

- Truncated Importance Sampling (TIS): A variance-controlled correction for train–rollout distribution shift using clipped importance weights. "we adopt Truncated Importance Sampling (TIS)~\citep{yao2025tis}, which applies importance weighting to rebalance gradients"

- vllm: A high-throughput inference engine for LLM sampling during rollouts. "rollout (e.g. vllm~\citep{kwon2023vllm} and SGLang~\citep{zheng2024sglang})"

- XVerify: An LLM-based verification paradigm that judges answer correctness beyond symbolic equivalence. "we follow the XVerify~\citep{chen2025xverify} paradigm and employ a LLM (Qwen3-30B-A3B-Instruct-2507) as an answer-level verifier."

Practical Applications

Overview

The paper introduces P1, an open-source family of physics reasoning models trained via reinforcement learning (RL), with test-time agentic augmentation using the PhysicsMinions framework. Key innovations include a curated physics dataset with rule-verifiable answers, a multi-stage RL post-training recipe (GSPO + truncated importance sampling + adaptive learnability control), a hybrid rule-based/model-based verification stack, and an agentic workflow for multi-turn reasoning and self-verification. Below are practical, real-world applications derived from these findings, organized by immediacy and linked to sectors and workflows where relevant.

Immediate Applications

These applications can be piloted or deployed now, using P1-30B-A3B or P1-235B-A22B, the PhysicsMinions agent framework, and the released dataset and training stack.

- Olympiad and advanced physics tutoring (education)

- Use case: Step-by-step coaching for high-school Olympiad-level and undergraduate physics, multi-turn reflection and correction via PhysicsMinions.

- Tools/products: “Physics Coach” web/app with solver + introspector + reviewers; curriculum-specific modules; LaTeX-native explanations; progress dashboards.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Text-only problems (no diagrams unless additional vision model is added); long-context inference cost; institutional policies on AI assistance; human oversight for edge cases.

- Automated grading and feedback for physics problem sets (education, software)

- Use case: Autograding multi-part answers using the paper’s multi-box output format and hybrid verification (SymPy rule-based equivalence + LLM verification).

- Tools/products: LMS plug-in; “Verifier-as-a-Service” for LaTeX/Markdown problem sets; rubric mirroring with partial credit via test-case style reward aggregation.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Rule-verifiable answers; consistent variable naming/units; robust parsing (PDF-to-Markdown pipeline); security and academic integrity controls.

- Physics-aware QA assistant for engineering calculations (aerospace, automotive, energy, robotics, semiconductors)

- Use case: Pre-simulation checks—derive governing equations, check unit consistency, constants, boundary conditions; identify calculation errors before ANSYS/COMSOL/MATLAB/Simulink runs.

- Tools/products: “Design Check” plug-in for CAD/CAE suites; PhysicsMinions Review Studio adapted as a “Unit & Constants Verifier.”

- Dependencies/assumptions: Expert-in-the-loop validation; integration APIs; text-to-tool interfaces; clear scope separation from numerical solvers (P1 focuses on reasoning/setup, not heavy computation).

- Manuscript math and physics verification (academia, publishing)

- Use case: Preprint and journal submission checks for derivations, units, symbolic equivalence, and consistency.

- Tools/products: Editorial “Scientific Verifier” integrated with LaTeX pipelines; arXiv/journal plug-ins to flag discrepancies.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to source equations; handle notation variants; privacy/compliance on manuscript data.

- Dataset and content creation pipeline for STEM (academia, edtech)

- Use case: Replicate the paper’s PDF-to-Markdown pipeline with multi-model cross-validation to build rule-verifiable problem corpora in math, chemistry, and engineering.

- Tools/products: “STEM Corpus Builder” toolkit; problem banks with Q–Solution–Answer schema and metadata; reusable SymPy checks.

- Dependencies/assumptions: License/compliance on source material; careful OCR correction; multilingual normalization.

- General reasoning assistant for math and programming (software)

- Use case: Contest-style math and coding tasks leveraging P1’s demonstrated transfer of reasoning skills beyond physics.

- Tools/products: “Contest Helper” agents; Code + Math hybrid reviewers with test-case style validation; problem-solving IDE extensions.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Task verifiability (unit tests for code, symbolic checks for math); careful prompt and output formatting.

- RL training recipe adoption for domain-specific reasoning models (software, AI tooling)

- Use case: Apply the paper’s multi-stage RL post-training strategy (GSPO, TIS, adaptive exploration) to other domains with verifiable outcomes (e.g., chemistry equations, circuit design).

- Tools/products: A “Science-RL” training stack built on slime + Megatron + SGLang; reusable reward design with test-case aggregation.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Availability of rule-verifiable datasets; compute for RL on large models; monitoring for entropy collapse and training plateaus.

- Benchmarking and evaluation standardization (academia, AI research)

- Use case: Adopt HiPhO as an evaluation benchmark to measure “science-grade” reasoning; publish leaderboard results for models and agentic frameworks.

- Tools/products: Open benchmark kits with scoring thresholds (Gold/Silver/Bronze equivalents); standardized reporting workflows.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Community consensus on evaluation criteria; transparent verifier configurations; reproducibility practices.

- Internal policy pilots for AI-assisted verification of safety-critical calculations (policy, energy, civil engineering)

- Use case: Use agentic multi-stage verification to cross-check unit-consistent calculations in internal reports and permit submissions (e.g., structural loads, grid components).

- Tools/products: “AI Calculation Audit” service; digital checklists driven by PhysicsMinions Review Studio.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Non-binding advisory status; liability and compliance considerations; audit trail logging; domain expert sign-off.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, multimodal capability, tighter tool integration, scaling, or regulatory acceptance.

- Multimodal physics reasoning with diagrams and schematics (education, engineering, robotics)

- Vision-enabled Visual Studio for interpreting plots, circuits, free-body diagrams, CAD drawings; full activation of PhysicsMinions’ visual pipeline.

- Potential products: “Diagram-to-Derivation” assistant; CAD-aware physics reviewers; robotic system planners that reason over sensor schematics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust vision-LLMs; diagram ground-truthing; standardized symbols and conventions; domain ontologies.

- Closed-loop design automation with simulation integration (aerospace, automotive, energy)

- Agent proposes equations, sets boundary conditions, runs simulation, critiques results, iterates until convergence or passing multi-stage verifications.

- Potential products: “Equation-to-Simulation” copilot; COMSOL/ANSYS/Simulink integration; automated verification stamps on design artifacts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Secure toolchain integration; APIs for bidirectional control; runtime budgets; guardrails to prevent unsafe recommendations.

- Certified AI verification for safety-critical engineering (policy, standards, compliance)

- Regulatory frameworks for AI-assisted verification; auditability and traceable agentic logs; standardized unit/constants libraries.

- Potential products: “AI Verification Stamp” with provenance; compliance dashboards for utilities, civil infrastructure, medical devices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal and standards body engagement; reliability thresholds and error metrics; incident response and liability models.

- AI-augmented experimental design and machine scientific discovery (academia, labs)

- Agents propose hypotheses, derive models, design experiments, simulate expected outcomes, and refine based on verification failures.

- Potential products: “Lab Minions” integrating ELN/LIMS; experiment planners for materials, optics, condensed matter, and fluid dynamics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Integration with instruments and data platforms; multi-agent orchestration; human-in-the-loop validation; risk management.

- Sector-specific physics copilots

- Healthcare: Medical physics (radiation therapy dosimetry, MRI parameter optimization) with unit/constraint-aware verification loops.

- Energy: Grid modeling, power electronics design checks, stability studies with verified derivations.

- Robotics: Dynamics and control law derivation, trajectory safety checks, hardware stress analyses.

- Climate and materials: PDE setup for climate models; symbolic derivations for material properties and transport phenomena.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain-specific datasets and ontologies; coupling with simulators; rigorous validation; ethical and safety frameworks.

- Cross-domain RLVR expansion to finance, law, and other fields with verifiable outcomes (finance, legal-tech)

- Transpose test-case style reward to ledger reconciliations, contract clause compliance, policy rules; GSPO/TIS training paradigms for structured reasoning.

- Potential products: “Rule-Verifiable Reasoner” for regulated domains; audit agents that check consistency against codified rules.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality, rule-verifiable corpora; precise formalization of rules; strong safeguards against hallucinations.

- Edge and low-resource deployments via model distillation (software, education, emerging markets)

- Distill P1’s physics reasoning into smaller models for classroom devices or offline use.

- Potential products: “P1-Lite” for schools and labs with limited compute; portable grading assistants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Distillation preserving reasoning fidelity; efficient long-context handling; privacy-preserving local inference.

- Educational policy and curriculum transformation (policy, education)

- Integrate AI-driven verification and personalized coaching into standardized assessments; redesign exams for rule-verifiable outputs.

- Potential products: National or district-level “AI in STEM” programs; frameworks for ethical use in competitions and classrooms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stakeholder buy-in; equity and access considerations; clear guidelines to prevent misuse and ensure learning outcomes.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Model size and compute budgets (especially 235B) affect deployment; 30B or hosted APIs are more accessible.

- Text-only capabilities limit direct handling of diagrams until multimodal components are added.

- Reliability hinges on rule-verifiable tasks and strong verification harnesses; human oversight remains essential.

- Long-context inference and multi-turn agentic loops increase cost/time; careful engineering and timeout policies are required.

- Open-source licensing, data provenance, and compliance need attention in production settings.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.