Multi-Agent Evolve: LLM Self-Improve through Co-evolution

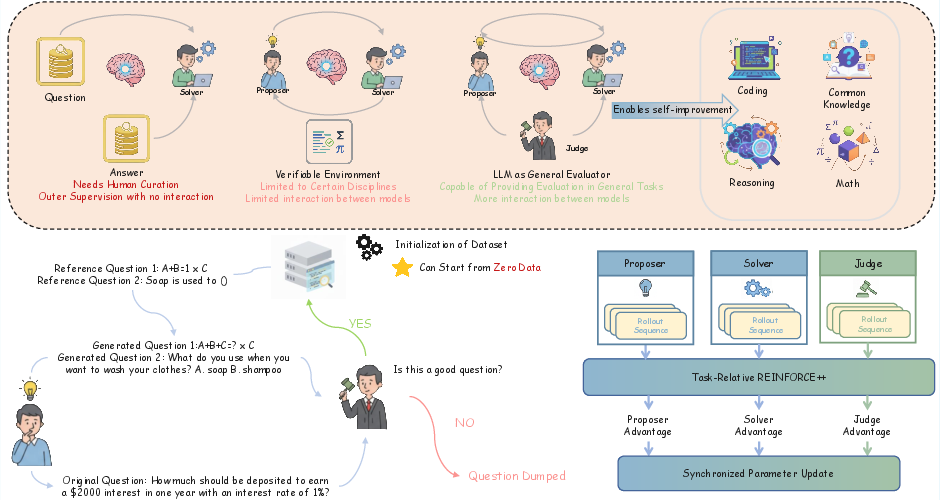

Abstract: Reinforcement Learning (RL) has demonstrated significant potential in enhancing the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. However, the success of RL for LLMs heavily relies on human-curated datasets and verifiable rewards, which limit their scalability and generality. Recent Self-Play RL methods, inspired by the success of the paradigm in games and Go, aim to enhance LLM reasoning capabilities without human-annotated data. However, their methods primarily depend on a grounded environment for feedback (e.g., a Python interpreter or a game engine); extending them to general domains remains challenging. To address these challenges, we propose Multi-Agent Evolve (MAE), a framework that enables LLMs to self-evolve in solving diverse tasks, including mathematics, reasoning, and general knowledge Q&A. The core design of MAE is based on a triplet of interacting agents (Proposer, Solver, Judge) that are instantiated from a single LLM, and applies reinforcement learning to optimize their behaviors. The Proposer generates questions, the Solver attempts solutions, and the Judge evaluates both while co-evolving. Experiments on Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct demonstrate that MAE achieves an average improvement of 4.54% on multiple benchmarks. These results highlight MAE as a scalable, data-efficient method for enhancing the general reasoning abilities of LLMs with minimal reliance on human-curated supervision.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching a LLM to get better at thinking and problem-solving on its own, without needing humans to label tons of data. The authors introduce a system called “Multi-Agent Evolve” (MAE), where one LLM plays three roles—Proposer, Solver, and Judge—and learns by having these roles work together and challenge each other. The goal is to make the model better at math, reasoning, coding, and general knowledge.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The paper focuses on a simple but important question: Can we help an LLM improve its reasoning skills by learning from itself, without relying on human-made answer keys or special tools (like code checkers or game engines)? More specifically:

- How can an LLM create useful practice questions, try to answer them, and fairly score itself?

- Can this self-improvement work across many topics (math, coding, general knowledge) instead of just one?

- How do we keep training stable and prevent the system from drifting into low-quality content?

How did they do it?

To make this approachable, think of MAE as a self-running quiz show with three characters, all played by the same LLM:

- Proposer: the quiz writer who creates questions.

- Solver: the contestant who tries to answer.

- Judge: the referee who scores the question and the answer.

Key ideas explained simply

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): This is like a video game for models. The model tries something, gets points (rewards) for doing well, and changes its strategy to earn more points next time.

- Self-Play: Instead of learning from a teacher, the model practices against itself—like a chess player playing against their own past versions.

- LLM-as-a-Judge: The model itself acts as a fair grader, giving scores based on clear rules. This lets the system train without human judges.

The three-agent setup

Here’s how each role earns points (rewards):

- Proposer’s rewards:

- Quality: Is the question clear, logical, and solvable?

- Difficulty: Is it challenging enough to push the Solver’s limits?

- Format: Is it written in the right structure so the system can read it?

- Solver’s rewards:

- Correctness: Does the answer actually solve the problem?

- Format: Is the answer placed where the system expects it?

- Judge’s rewards:

- Clean output: Does the Judge give a score in the right format so it can be saved and used?

Keeping training stable

To avoid messy or useless training:

- Quality filtering: Only questions that the Judge says are “good enough” are kept and reused.

- Format rewards: The system gives extra points for using neat, consistent tags (like putting the question inside <question> tags). This makes automatic grading and training possible.

- Balanced challenge: The Proposer earns more when it makes questions that are hard-but-solvable. That keeps training productive rather than frustrating.

The training loop (simple view)

Here’s what happens repeatedly:

- Proposer creates new questions.

- Solver attempts answers.

- Judge scores both the question and the answer.

- The model updates all three roles at once based on the scores.

- Good questions and answers are saved to a growing practice set.

Sometimes the Proposer uses “reference questions” (examples from real datasets, but without the answers) to guide what kinds of questions to make. Other times it invents questions from scratch.

What did they find?

The authors tested MAE on the Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct model and compared it to:

- The original base model (no self-improvement),

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) using human answers,

- Another self-play method called AZR (Absolute Zero Reasoner), which relies more on special tools.

Main results:

- MAE improved the model across many tasks, with about a 4–5% average boost.

- It worked even without ground-truth (human) answers.

- It outperformed standard supervised fine-tuning (SFT) in many cases, even though SFT had access to real answers.

- A “half reference” setup—mixing some guidance from sample questions with new self-made questions—gave the best overall performance.

- MAE beat AZR on broad reasoning tasks because it doesn’t depend on specific tools (like compilers or game engines) to check correctness.

Why this matters:

- The model learned to write better questions over time, which helped the Solver improve.

- Hard-but-solvable questions (“desirable difficulty”) improved learning more than easy or impossible questions.

- Training stayed stable over many steps because of quality filtering and clean output formatting.

What does this mean for the future?

MAE shows that LLMs can teach themselves to think better across different domains without massive human-labeled datasets. This could:

- Make training cheaper and more scalable,

- Help models improve in areas where humans don’t have ready-made answer keys,

- Lead to more general, self-sufficient AI systems that can grow their abilities over time.

The authors suggest future work like scaling to bigger models, adding more roles, and combining this approach with places where answers can be automatically checked (like math solvers or code runners). This could create an even stronger, unified platform where AI models continuously evolve with minimal human supervision.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

The following items summarize what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper and suggest concrete directions for future research.

- Reliance on LLM-as-judge for both training rewards and evaluation, without rigorous calibration studies of judge accuracy, bias, and failure modes across domains; no human evaluation to validate judge reliability.

- Potential reward hacking and over-optimization to the judge’s rubric (Goodhart’s law): no quantitative analysis of whether Proposer/Solver exploit judge-specific styles, phrasing, or CoT patterns to inflate scores without truly improving correctness.

- Self-referential evaluation bias: the training judge and the evaluation judge are both LLMs; no experiments with independent judges (different model families, ensembles, or frozen evaluators) to reduce circularity.

- Score drift risk: the Judge’s parameters are updated (albeit only with format rewards), yet no monitoring of score scale/calibration drift over training, nor normalization to ensure comparability of scores over time.

- Ambiguity in difficulty reward safety: difficulty is defined as 1 − average judge score, but it can incentivize unsolvable/ambiguous questions; the paper asserts quality filtering mitigates this, yet lacks metrics showing how often unsolvable or adversarial questions are generated and filtered.

- Fixed and equal reward weights (quality/difficulty/format) are not tuned or ablated; no sensitivity analysis to weighting schemes and their impact on stability and outcomes.

- Unspecified and unablated N_sample for difficulty estimation; no cost–accuracy trade-off analysis of sampling more Solver answers versus training efficiency.

- Format reward narrowly targets tag correctness; no exploration of more robust structural guarantees (e.g., schema/JSON output, constrained decoding, parser-based validation) and their effect on stability and downstream performance.

- Shared-parameter triad (Proposer/Solver/Judge) is updated synchronously; no investigation of role-specific adapters, partial freezing, or separate models per role to mitigate negative transfer and role contamination.

- No comparison of synchronous versus asynchronous updates, or alternative multi-agent training schedules (e.g., alternating optimization, decoupled judge updates) and their stability implications.

- Lack of theoretical analysis or guarantees (e.g., convergence, equilibrium properties, or conditions under which co-evolution improves generalization), especially given non-verifiable rewards.

- Limited baseline coverage: comparisons only to SFT (LoRA) and AZR; missing baselines such as RLAIF, RLHF/RLVR variants without verifiers, self-training/pseudo-labeling, or multi-agent debate/voting methods.

- Baseline fairness concerns: SFT uses LoRA-128 whereas MAE appears to update full-model parameters; the impact of parameterization and training budget on performance is not controlled.

- Compute, training cost, and efficiency are not reported (steps, wall-clock, tokens, sampling K per step); no scaling curves or sample/compute efficiency comparisons versus baselines.

- Single backbone model (Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct) only; no evidence of generality across model families, sizes, or instruction-following characteristics, nor scaling-law analysis.

- Contamination control: seed data include questions from datasets overlapping with evaluated benchmarks; no explicit verification of train–test leakage or contamination risks beyond the LiveBench mention.

- No multi-run variance, confidence intervals, or statistical significance testing; improvements may be within noise—reproducibility with multiple seeds is not reported.

- Evaluation relies on an LLM judge for correctness matching on most benchmarks; lacks exact-match or domain-native metrics where applicable, and does not assess whether MAE’s output style is preferentially favored by the judge.

- LiveBench Reasoning performance degrades for the best MAE setting relative to SFT; no analysis of why certain reasoning benchmarks regress and how to remedy this.

- Safety and robustness are not evaluated: no assessment of harmful, biased, or deceptive question/answer generation, nor any safety-aware rubrics or filters integrated into the Judge.

- Long-run stability beyond ~250 steps is not demonstrated; no analysis of catastrophic forgetting, cyclical collapse, or the impact on general instruction-following abilities.

- Dataset curation effects are underexplored: no ablation on quality threshold (0.7), distribution shifts induced by filtering, or the size/composition of the seed dataset (e.g., domain balance, question types).

- No study of Proposer prompt/reference strategies beyond “no/half/with reference”: missing controlled analyses for paraphrase distance, difficulty targeting, or curriculum schedules to shape the evolving dataset.

- Difficulty–learning relationship is illustrated but not quantified; lacks formal metrics for “desirable difficulty” ranges and adaptive policies to maintain target difficulty over training.

- Judge rubric design is not validated (e.g., inter-rater reliability across judges, alignment with ground truth metrics); no exploration of richer rubrics (factuality, calibration, reasoning steps) or multi-criteria aggregation.

- Coding tasks uniquely use verifiable environments (Evalplus), whereas other domains do not; open question on integrating lightweight verifiers (e.g., calculators, knowledge bases) and blending verifiable and non-verifiable rewards.

- Inference-time format adherence and extraction robustness for evaluation are not reported; extraction failures may bias results—no audits of parse error rates across methods.

- Lack of generality to non-text or interactive settings (e.g., tool use, embodied tasks, web agents); open question: how to incorporate external environments and tools in a unified co-evolution framework.

- No explicit measurement of trade-offs (e.g., gains in math vs. losses in reasoning or truthfulness), or multi-objective optimization strategies to balance domain-specific improvements.

- Missing details for full reproducibility: prompts (beyond appendix reference), RL hyperparameters (temperature, K completions, baselines), optimizer settings, and data pipelines are not fully specified.

Glossary

- Adversarial Interaction: A process where competing agents, such as a solver and a proposer, engage in an environment designed to test their capabilities against one another. Example: "The Proposer and Solver engage in an adversarial interaction: the Solver is rewarded by the Judge for accurate and well-reasoned answers, while the Proposer receives both a quality reward from the Judge and a difficulty reward that increases when the Solver fails, driving co-evolution toward more challenging and informative tasks."

- Co-evolution: A framework for mutual adaptation and enhancement of agents or models, often through interaction and feedback loops, leading to improved performance. Example: "The core design of MAE is based on a triplet of interacting agents (Proposer, Solver, Judge) that are instantiated from a single LLM, and applies reinforcement learning to optimize their behaviors."

- Difficulty Reward: A scoring system that increases when a solver struggles with a question, incentivizing the generation of challenging yet solvable queries. Example: "The difficulty reward is designed to be high only when the question is challenging for the Solver."

- Format Reward: A specialized reward to ensure that outputs by agents are structured or formatted correctly for parsing and further evaluation. Example: "The Solver also receives a format reward to ensure its generation is placed inside the requested <answer> tags for correct parsing."

- General-Domain Reward Signals: Non-specific, domain-agnostic feedback provided to models, allowing them to self-assess and improve without human oversight. Example: "Multi-Agent Evolve\ instantiates three interactive roles (Proposer, Solver, and Judge) from a single LLM to form a closed self-improving loop."

- Inter-agent Dynamics: The interactions between multiple agents or roles within a system, contributing to mutual adaptation and learning. Example: "The interactions among different roles form the foundation of our framework, naturally requiring each agent's actions to be diverse to ensure overall diversity."

- Judge-based Evaluation: An assessment method using a designated agent or model to score or rate the performance of actions taken by other agents within a system. Example: "We design domain-agnostic self-rewarding mechanisms, including Judge-based evaluation, difficulty-aware rewards, and format rewards, which eliminate the reliance on human-labeled ground truth."

- Multi-Agent Evolve (MAE): A framework leveraging the interactions among multiple roles to enable LLMs to self-improve through reinforcement learning, without needing human supervision. Example: "To address these challenges, we propose Multi-Agent Evolve (MAE), a multi-agent self-evolving framework that extends the Self-Play paradigm to general domains."

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): A machine learning approach where an agent learns to make decisions by performing actions and receiving feedback from the environment to maximize cumulative reward. Example: "Reinforcement Learning (RL) has demonstrated substantial potential in training LLMs, leading to notable improvements in tasks such as coding and reasoning."

- Self-Rewarding Loop: A feedback loop where a system generates its own rewards based on internal evaluations, facilitating self-improvement. Example: "This design forms a self-rewarding loop where the model can assess and improve itself without external supervision or domain-specific ground truth."

- Self-Play: A method where a model or agent interacts with versions of itself to improve performance in tasks without external data or supervision. Example: "Self-Play is a data-free approach that requires minimal human supervision. It primarily relies on the system's capabilities and its self-interaction to enable higher intelligence to emerge."

- Task-Relative REINFORCE++: An adaptation of the REINFORCE algorithm used to compute separate baselines for each agent in a multi-agent system, aiming for variance reduction and improved training stability. Example: "We follow Absolute Zero Reasoner and use Task-Relative REINFORCE++, which computes separate baselines for each agent."

- Verifier-Free Training: A process where models are trained without external validation or ground-truth, relying on internal metrics and dynamics for self-improvement. Example: "Verifying environments to build a unified platform where models can evolve across all general domains without human supervision."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the paper’s methods and findings, with careful attention to assumptions and dependencies.

Industry

- Continuous self-improvement for enterprise LLMs (sectors: software, customer support, knowledge management)

- Use MAE’s proposer–solver–judge loop to fine-tune internal models on domain-specific tasks (e.g., troubleshooting, FAQs, policy Q&A) without labels. Seed the Proposer with unlabeled internal documents and ticket archives to generate realistic, difficult cases; the Solver answers; the Judge scores for correctness and clarity; quality filtering preserves dataset integrity.

- Tools/workflows: “MAE Orchestrator” (role coordination and synchronized updates), “Judge Rubric Manager” (domain-specific scoring guidelines), “Quality Filter Dashboard,” “Task-Relative REINFORCE++ Trainer” integrated into MLOps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable LLM-as-a-judge calibration for the domain; sufficient compute; seed questions representative of domain; guardrails to avoid reward hacking or drift; ongoing human spot-auditing.

- Synthetic test generation for codebases and developer enablement (sectors: software)

- Proposer generates coding tasks and test cases aligned to a codebase; Solver drafts implementations or patches; Judge evaluates answers (style/logic) and format adherence; use as a pre-commit CI assistant to expand unit/integration tests and “explain” code paths.

- Tools/workflows: “Synthetic Test Generator,” “Code Reasoner Self-Training,” CI integration that optionally routes questionable cases to verifiable environments (interpreters/runners).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Without a runtime verifier, Judge may mis-score correctness; integration with interpreters recommended; code security and IP constraints; rubric specificity for language/frameworks.

- Knowledge base curation and Q&A hardening (sectors: software, customer support, enterprise knowledge)

- MAE generates “desirably difficult” questions against knowledge articles; Solver answers; Judge prunes ambiguities and identifies missing coverage; outputs a prioritized backlog for KB enhancements and fine-tunes Q&A models.

- Tools/workflows: “KB Coverage Analyzer,” “Difficulty-Aware Curriculum Builder,” “Judge-driven Quality Gate.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain rubrics aligned to enterprise style guides; continuous monitoring for hallucinations; permissioning for sensitive content.

- Safety and compliance red-teaming (sectors: software, governance)

- Proposer generates adversarial prompts (jailbreaks, policy edge cases); Solver responds; Compliance Judge scores adherence to policies; use MAE to harden models without manual annotation.

- Tools/workflows: “Adversarial Prompt Generator,” “Compliance Judge,” “Policy Rubric Designer.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Well-specified policies and rubrics; Judge bias and false positives; periodic external audits.

Academia

- Adaptive practice problem generation and auto-grading (sectors: education)

- Proposer produces solvable yet challenging questions (math, CS, reasoning); Solver attempts answers; Judge provides granular scores using rubrics. Deployed in LMS for homework and formative assessment with difficulty-aware progression.

- Tools/workflows: “Synthetic Curriculum Engine,” “Auto-Grader (Judge),” LMS plug-in for quality filtering and question rotation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rubrics tuned to syllabus; human moderation for edge cases; safeguards against cultural/knowledge biases; transparent scoring explanations for students.

- Dataset bootstrapping and benchmark expansion (sectors: research)

- Generate diverse, quality-filtered tasks for low-resource domains/languages; use Judge for initial scoring and triage; selectively sample for human validation to build new benchmarks.

- Tools/workflows: “Dataset Augmentor,” “Benchmark Composer,” human-in-the-loop QC harness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Bias propagation risks; careful sampling and stratification; periodic human calibration.

Policy and Public Sector

- Model evaluation and audit harness (sectors: policy, public sector)

- Use LLM-as-a-Judge to score outputs on compliance, clarity, and evidence use; MAE-cycled datasets stress-test assistants for citizen services and legal/administrative queries.

- Tools/workflows: “LLM Audit Bench,” “Compliance Rubric Manager,” “Synthetic Stress-Test Suite.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standards for judge reliability; privacy and FOIA constraints; independent audit for fairness; domain-specific calibration.

Daily Life

- Personal study and interview preparation (sectors: education, career coaching)

- MAE-based tutor generates tailored questions (with difficulty control), evaluates answers, and builds a study plan; useful for test prep (e.g., math, logic, coding) and behavioral/technical interviews.

- Tools/workflows: “MAE Tutor,” “Interview Prep Coach,” mobile app with explainable Judge feedback and format rewards for clean parsing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Verify correctness of answers on critical topics; configurable rubrics to align with exam standards; parental/teacher dashboards for minors.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, integration with verifiable environments, and/or regulatory development.

Industry

- Unified self-evolving LLM platform across tools and modalities (sectors: software, robotics, energy)

- Expand MAE with tool integration (interpreters, simulators, retrieval, APIs) to yield verifiable rewards; orchestrate multi-role agents that propose tasks, solve with tool use, and judge via both LLM and external metrics; continuously improve enterprise assistants across domains.

- Tools/products: “Autonomous Reasoning Lab,” “MAE SDK,” “Tool-Verified Judge,” “Curriculum Planner” for multi-domain portfolios.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust orchestration at scale; cost control; tool reliability; safety/alignment with business policies; continuous evaluation pipelines.

- Autonomous software modernization and maintenance (sectors: software)

- Proposer identifies refactoring opportunities and dead code; Solver drafts patches and migration plans; Judge verifies with tests and static analysis; full lifecycle automation for legacy-to-modern stack transitions.

- Tools/workflows: “Code Modernizer,” “Auto-Refactor Planner,” “Judge-Backed CI/CD.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Integration with compile/run-time verifiers; rollback safety; change management policies; regulatorily compliant logs.

Academia

- Scientific discovery agents (sectors: research, R&D)

- Multi-agent triads propose hypotheses, design experiments (Solver via simulations/lab protocols), and judge results using domain rubrics and statistical criteria; accelerate literature-driven exploration and hypothesis refinement.

- Tools/workflows: “AutoHypothesis Generator,” “Experiment Planner,” “Statistical Judge.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to reliable simulations/experimental data; methods to avoid confirmation bias; reproducibility checks; ethical oversight.

- Psychometrically validated assessment at scale (sectors: education)

- Use MAE to design standardized tests and adaptive assessments; calibrate difficulty via item-response theory and fairness audits; deploy globally across curricula.

- Tools/workflows: “Assessment Composer,” “IRT-Calibrated Judge,” fairness/explainability dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rigorous psychometric validation; demographic fairness; accreditation approvals; transparent scoring standards.

Policy and Public Sector

- Synthetic data governance and audit standards

- Develop standards for LLM-as-a-Judge reliability, synthetic dataset provenance, and self-training audits; certify MAE-like pipelines for public deployments (health, justice, education).

- Tools/workflows: “Auditable Self-Training Protocols,” “Synthetic Data Registry,” “Judge Calibration Suite.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder governance; regulatory frameworks; independent evaluation bodies; privacy-by-design.

Sector-Specific High-Stakes Domains

- Healthcare decision support (sectors: healthcare)

- Proposer generates diverse clinical cases; Solver suggests differential diagnoses/management; Judge scores adherence to guidelines; ultimately integrate with verifiable outcomes (EHR, trials) for safe reinforcement signals.

- Tools/workflows: “Synthetic Patient Case Engine,” “Clinical Guideline Judge,” EHR-integrated verification.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory compliance (HIPAA/GDPR), clinician-in-the-loop review, medical device approval pathways, robust grounding to evidence.

- Finance risk scenario modeling (sectors: finance)

- Proposer crafts rare stress scenarios; Solver models portfolio responses or hedging strategies; Judge evaluates using backtests and risk metrics; continuous improvement of risk engines.

- Tools/workflows: “ScenarioLab,” “Backtest-Verifier Judge,” risk dashboard integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensed market data; robust backtesting infrastructure; regulatory constraints; model risk management.

- Robotics and autonomous systems (sectors: robotics)

- Proposer designs curriculum tasks for manipulation/navigation; Solver plans actions; Judge scores using simulation telemetry and safety constraints; transfer to real-world with verified rewards via sensors.

- Tools/workflows: “Robot Curriculum Engine,” “Sim-to-Real Judge,” multi-agent orchestration for embodied tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity simulators; safety certification; sim-to-real domain adaptation; hardware constraints.

Cross-Cutting Tools and Products That May Emerge

- MAE SDK and orchestration platform for multi-role LLM training (plug-ins for Proposer/Solver/Judge prompts, rubrics, quality filtering, and synchronized updates).

- Judge Rubric Designer with template libraries for domains (math, coding, compliance, healthcare).

- Difficulty-aware Synthetic Curriculum Builder with monitored dataset health metrics and bias checks.

- Tool-Verified Judge adapters for interpreters, compilers, simulators, and retrieval systems.

- Continuous Self-Evolve Trainer integrated in MLOps (versioning, audit logs, rollback).

Common Assumptions and Dependencies Affecting Feasibility

- LLM-as-a-Judge reliability and bias: rubrics must be well-specified; calibration and periodic human audits are needed.

- Verifiable rewards: for code, robotics, healthcare, and finance, external verifiers and ground truth are essential to avoid reward hacking and hallucinations.

- Compute and scaling: synchronized multi-agent updates require significant resources, especially for larger backbones.

- Seed dataset quality and representativeness: poor seeds can bias the generated curriculum; quality filtering mitigates but does not eliminate this risk.

- Data governance and privacy: synthetic generation must respect IP, confidentiality, and regulatory constraints.

- Monitoring and safety: continuous detection of format, quality, and policy violations; guardrails against drifting into unsolvable or unsafe tasks.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.