Gradient Descent as Implicit EM in Distance-Based Neural Models (2512.24780v1)

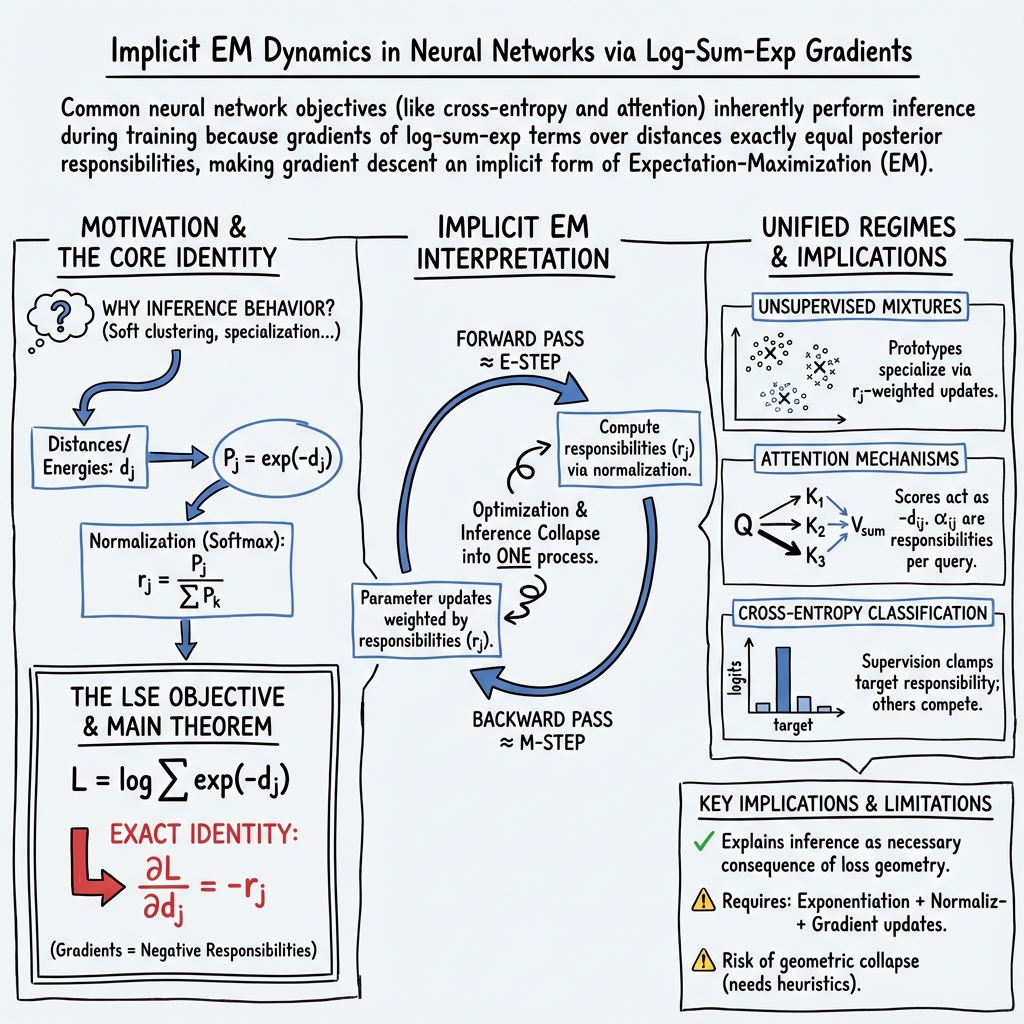

Abstract: Neural networks trained with standard objectives exhibit behaviors characteristic of probabilistic inference: soft clustering, prototype specialization, and Bayesian uncertainty tracking. These phenomena appear across architectures -- in attention mechanisms, classification heads, and energy-based models -- yet existing explanations rely on loose analogies to mixture models or post-hoc architectural interpretation. We provide a direct derivation. For any objective with log-sum-exp structure over distances or energies, the gradient with respect to each distance is exactly the negative posterior responsibility of the corresponding component: $\partial L / \partial d_j = -r_j$. This is an algebraic identity, not an approximation. The immediate consequence is that gradient descent on such objectives performs expectation-maximization implicitly -- responsibilities are not auxiliary variables to be computed but gradients to be applied. No explicit inference algorithm is required because inference is embedded in optimization. This result unifies three regimes of learning under a single mechanism: unsupervised mixture modeling, where responsibilities are fully latent; attention, where responsibilities are conditioned on queries; and cross-entropy classification, where supervision clamps responsibilities to targets. The Bayesian structure recently observed in trained transformers is not an emergent property but a necessary consequence of the objective geometry. Optimization and inference are the same process.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A Simple Guide to “Gradient Descent as Implicit EM in Distance-Based Neural Models”

1) What is this paper about?

This paper explains why many neural networks (like those with attention or trained with cross-entropy) naturally behave as if they are doing a kind of smart “grouping and updating” process from statistics, called expectation–maximization (EM). The key idea is that when a network uses a softmax-like formula over “distances” (how far an input is from different learned reference points), the learning signals it gets are exactly the same as the “how responsible was each option?” numbers EM would compute. In short: the network doesn’t just learn; it also quietly does inference about which part of itself should explain each input.

2) What questions does it ask?

- Why do trained neural networks often show “soft clustering,” specialization into roles, and uncertainty handling—things that look like probabilistic reasoning—even when we didn’t program them to do that?

- Is this behavior an accident of architecture, just because we used softmax, or something deeper?

- Can we prove, not just suggest, that the training process itself is automatically doing EM-like inference?

3) How did the authors study it?

The paper looks at a very common mathematical shape in neural network losses: the log-sum-exp over distances (or energies). Think of several “teams” (components) trying to explain an input. Each team has a “distance” measuring how well it fits the input (smaller is better). The loss is:

- Turning distances into is like saying “closer fits get bigger votes.”

- Dividing by the total makes those votes a probability-like split (softmax), so the votes across teams add up to 1. That split is called responsibility :

The main math step (just basic calculus) shows:

What does that mean in everyday terms? When we train with gradient descent, we update parameters based on gradients. This result says the signal sent to “team ” is exactly its responsibility—how much it should claim the input. In classic EM, you first compute responsibilities (E-step) and then update parameters weighted by those responsibilities (M-step). Here, you don’t compute them separately: they appear directly as gradients during training. So the forward pass sets up the “votes,” and the backward pass applies them—EM is built into the normal training process.

A few plain-language ingredients make this work:

- Exponentiation (turn distances into positive “votes”).

- Normalization (softmax makes the votes sum to 1, forcing competition).

- Gradient-based learning (so these responsibilities actually drive the updates).

If any of these is missing, the EM-like behavior doesn’t appear.

4) What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the main takeaways:

- Responsibilities are gradients: The paper proves an exact identity, not a rough analogy:

- The gradient with respect to each distance equals minus that component’s softmax responsibility.

- So training already does what EM does: “figure out who’s responsible” and update that part more.

- One mechanism, three places:

- Unsupervised mixtures: With no labels, components (like cluster centers) softly compete to explain each input. Each gets updated in proportion to its responsibility .

- Attention: Attention weights are responsibilities conditioned on a query. The values and projection matrices get updated more when they are more responsible for the output. So attention is conditional mixture inference.

- Cross-entropy classification: The label “clamps” the correct class to responsibility 1. The gradient for the right class is (pull it closer); for wrong classes it’s (push them away in proportion to how much they tried to “claim” the input). It’s still responsibility-driven learning, just guided by labels.

- Why it matters:

- It explains why networks often look Bayesian (they track uncertainty and split credit across options). It’s not a coincidence—it’s forced by the geometry of common losses.

- It unifies different areas (clustering, attention, classification) under the same principle: exponentiate distances, normalize, and let gradient descent do the rest.

5) What could this change or influence?

- Clearer interpretation: If you ask “which part of the model handled this input?”, the answer is in the gradients: they’re the responsibilities. That gives a practical handle for analyzing models.

- Better loss design: Softmax/log-sum-exp doesn’t just “stabilize” training—it creates competition and produces EM-like learning. If you want this kind of inference, use it. If you want independent decisions (like multi-label cases), don’t use it.

- Understanding limits:

- No softmax, no competition: If outputs don’t compete (for example, independent sigmoids), there are no responsibilities and no implicit EM.

- Closed-world effect: Softmax forces all weight onto known options—there’s no “none of the above” unless you design for it.

- Collapse risk: Without extra terms that control scale (like in full Gaussian mixtures), models can over-concentrate. In practice, regularizers and norms help, but it’s good to know why the risk exists.

Overall, the paper’s message is simple but powerful: when networks use a log-sum-exp over distances and are trained by gradients, optimization and inference become the same process. The network doesn’t just learn parameters; it automatically figures out which parts should be responsible for each input—and uses that to learn better next time.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, framed to be actionable for future research.

- Formal convergence guarantees for “implicit EM”: Provide a proof (or counterexamples) that gradient flow/SGD on enjoys EM-like monotonic improvement of (marginal) likelihood, characterize stationary points, and identify conditions under which step sizes, stochasticity, and noise break EM’s ascent property.

- Parameter-level equivalence to an M-step: Beyond , derive when parameter updates for common parameterizations (e.g., class means/covariances, linear classifier weights, attention’s ) provably match the M-step of a concrete latent-variable model (i.e., a true maximization of ), and quantify deviations when they do not.

- Role of temperature and priors: Generalize the main identity to and analyze how and learned/non-uniform alter responsibility magnitudes, learning dynamics, and stability; provide guidance for temperature annealing schedules with theoretical guarantees.

- Impact of optimizer preconditioning: Analyze how momentum, Adam, Adagrad, and second-order methods transform responsibility-weighted signals at the parameter level (i.e., when updates are no longer simply proportional to ), and identify conditions or reparameterizations that preserve the EM-like weighting.

- Mini-batch and sampling effects: Quantify bias/variance introduced by mini-batch SGD, sampled softmax, and negative sampling (NCE/InfoNCE) on responsibility estimation; specify regimes where these approximations yield consistent gradients for “implicit E-steps.”

- Attention-specific derivations at scale: Provide a full derivation of responsibility-weighted updates for multi-head attention with residuals, layer norm, dropout, masking (causal/padding), and positional encodings; characterize interactions across heads and layers and identify when specialization (E/M timescale separation) provably emerges.

- Diagnostics and measurement: Develop practical tools to extract and track responsibilities from gradients during training (e.g., head/component responsibility profiles over time), measure specialization, detect collapse, and flag deviations from predicted implicit-EM behavior.

- Collapse and volume control: Design and analyze principled “volume” regularizers (e.g., log-determinant analogs, Jacobian penalties, spectral or covariance constraints) that prevent degenerate solutions under LSE objectives; quantify trade-offs with accuracy and calibration.

- Distance/energy semantics beyond piecewise-linear networks: Rigorously establish when deep networks with GELU/SiLU, normalization layers, and residual pathways still admit a distance/energy interpretation sufficient for the main identity to imply meaningful “posteriors.”

- Calibration of responsibilities: Determine conditions under which are calibrated posteriors rather than arbitrary normalized scores; study the role of proper scoring rules, temperature scaling, and regularization in aligning responsibilities with true probabilities.

- Alternatives to softmax normalization: Extend or contrast the analysis for sparsemax/entmax, top- softmax, and other normalizers; derive responsibility-like gradients (including zero-support cases) and evaluate their effects on interpretability, sparsity, and stability.

- Multi-label and non-competitive settings: Propose and analyze objectives that allow partial responsibilities without a closed-world constraint (e.g., group-wise or hierarchical normalizations) so that “implicit EM” can be meaningful beyond mutually exclusive classes.

- Open-set recognition and non-assignment: Specify concrete objectives that incorporate an explicit reject option or thresholded partition function; derive their gradients and study how responsibilities can vanish (or remain unassigned) for OOD inputs without harming in-distribution performance.

- Contrastive/self-supervised objectives: Map InfoNCE and related losses to the LSE framework, identify components/assignments in these settings, and test whether responsibility-weighted updates explain representation specialization in self-supervised learning.

- Masking, sparsity, and routing: Analyze how attention masking, sparsity-inducing penalties, and Mixture-of-Experts gating (explicit or implicit) interact with responsibility gradients; identify conditions for stable specialization vs. brittle over-routing.

- Interaction with label noise and soft supervision: Extend the constrained-regime analysis to probabilistic/ambiguous labels, label smoothing, and weak supervision; formalize how such supervision partially clamps responsibilities and affects convergence and generalization.

- Empirical breadth and falsification: Provide systematic experiments across architectures (Transformers, CNNs, MLPs), modalities (vision, language, audio), and losses (classification, contrastive, energy-based) that directly test the predicted responsibility-weighted dynamics and identify domains where the mechanism fails.

- Literature positioning and novelty boundaries: More thoroughly reconcile the identity with prior EBM, logistic regression, and softmax-gradient results; delineate what is genuinely new (implicit EM as a unifying mechanism) versus known calculus, and map precise overlaps with classical derivations.

- Continuous latents and variational objectives: Investigate whether and how the “implicit EM” view extends to continuous latent-variable models and variational training (e.g., ELBOs), and whether analogous responsibility-like gradient decompositions exist under amortized inference.

- Scalability and compute: Develop memory/compute-efficient methods to monitor or exploit responsibilities (e.g., low-rank or sketching approaches) in very large vocabularies or token counts, and quantify the cost-benefit trade-offs.

Glossary

- Advantage-like rule: A training dynamic analogous to the reinforcement learning advantage function that adjusts scores based on relative benefit. "attention scores adjust according to an advantage-like rule."

- Attention mechanisms: Neural operations that compute weighted combinations of values by normalizing query–key similarities. "in attention mechanisms, classification heads, and energy-based models"

- Bayesian inference: Inferring posterior probabilities over latent causes given data and priors. "robustness patterns reminiscent of Bayesian inference, down-weighting outliers and tracking uncertainty across inputs."

- Bayesian posteriors: The posterior distributions over hypotheses after observing data. "small transformers reproduce Bayesian posteriors with sub-bit precision."

- Bayesian uncertainty tracking: Maintaining a probabilistic measure of uncertainty throughout computation. "soft clustering, prototype specialization, and Bayesian uncertainty tracking."

- Closed-world assumption: The constraint that all probability mass must be assigned to known classes, leaving no “none of the above” option. "A consequence is the closed-world assumption."

- Conditional mixture inference: Mixture-model inference conditioned on a query, recomputed per input. "Attention is conditional mixture inference."

- Coordinate-ascent EM: A variant of expectation–maximization that performs coordinate ascent on the objective. "not to coordinate-ascent EM or guarantees about convergence."

- Cross-entropy classification: A supervised objective comparing predicted softmax distributions to target labels. "In cross-entropy classification, the logits act as negative distances"

- Energy-based models: Models that define an energy function over configurations, with probabilities derived via exponentiation and normalization. "in attention mechanisms, classification heads, and energy-based models"

- E-step: The responsibility-computation step of EM that assigns data points to components probabilistically. "In the E-step, responsibilities are computed."

- Expectation-Maximization (EM): An algorithm alternating between computing responsibilities (E-step) and updating parameters (M-step). "gradient descent on such objectives performs expectation-maximization implicitly"

- Free energy: An energy-based quantity whose gradients relate to probabilistic responsibilities after normalization. "the 'free energy' formulation in energy-based models."

- Gaussian kernels: Radial basis functions derived from Gaussian distributions used for similarity measures. "objectives based on Gaussian kernels without a partition function"

- Gaussian mixture models: Probabilistic models representing data as a mixture of Gaussian components. "This is precisely the M-step dynamic of Gaussian mixture models"

- Log-determinant term: A likelihood penalty on covariance volume in Gaussian models that prevents collapse. "includes a log-determinant term in the likelihood"

- Log marginal likelihood: The log of the probability of data under a model, marginalizing over latent components. "This is the log marginal likelihood---the log-probability that some component generated it."

- Log-sum-exp (LSE): A smooth maximum operator used as an objective, often after exponentiating negative distances. "This is the log-sum-exp (LSE) objective."

- Mahalanobis distance: A distance measure that accounts for covariance structure of the data. "the Mahalanobis distance of a point from a Gaussian component"

- Maximum correntropy: A robust objective based on correntropy that reduces the influence of outliers. "such as maximum correntropy:"

- Mixture modeling: Learning models where data is generated by a mixture of latent components. "unsupervised mixture modeling, where responsibilities are fully latent"

- Mixture of Experts: Architectures with explicit gating to route inputs to specialized subnetworks. "Mixture of Experts models use explicit gating networks to route inputs to specialized subnetworks."

- M-step: The parameter-update step of EM weighted by responsibilities. "In the M-step, parameters are updated."

- Open-set recognition: Recognizing when inputs do not belong to any known class, enabling rejection. "Open-set recognition, out-of-distribution detection, and selective prediction require objectives that break the closed-world assumption"

- Out-of-distribution detection: Identifying inputs that differ significantly from the training distribution. "Open-set recognition, out-of-distribution detection, and selective prediction require objectives that break the closed-world assumption"

- Partition function: The normalization constant that sums unnormalized likelihoods across alternatives. "denote the partition function."

- Posterior responsibility: The normalized probability that a component explains an observation. "the negative posterior responsibility of the corresponding component"

- Prototype specialization: The differentiation of learned prototypes to cover distinct regions or roles. "soft clustering, prototype specialization, and Bayesian uncertainty tracking."

- Selective prediction: Choosing not to make a prediction when confidence is insufficient. "Open-set recognition, out-of-distribution detection, and selective prediction require objectives that break the closed-world assumption"

- Soft clustering: Assigning data points probabilistically across clusters rather than hard labels. "soft clustering, prototype specialization, and Bayesian uncertainty tracking."

- Softmax normalization: Exponentiation and normalization that converts scores into a probability distribution. "design choices like softmax normalization"

- Unnormalized likelihood: A raw likelihood-like quantity before dividing by the partition function. "Let denote the unnormalized likelihood of component ."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are specific, deployable use cases that leverage the paper’s core result — that in log-sum-exp (LSE) objectives over distances/energies, the gradient with respect to each distance equals the negative responsibility — and its unifying view of attention, classification, and mixture learning.

- Responsibility-aware training diagnostics and dashboards (Software/ML Ops)

- Description: Build a “Responsibility Meter” that logs

r_j(via softmax over distances or directly from∂L/∂d_j) during training to monitor component/class attention, specialization, and misassignment. - Tools/Workflows: Plugins for PyTorch/TensorFlow to visualize responsibility distributions per layer/head/class; alerts when responsibility collapses to single components; heatmaps for attention heads.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: LSE/softmax normalization; gradient-based training; access to backward pass signals in training environments.

- Description: Build a “Responsibility Meter” that logs

- Responsibility-based explainability reports (Healthcare, Finance, Policy compliance, Education)

- Description: At inference, report per-decision responsibility allocations (softmax over logits/attention scores) to show which components/classes/sources “took responsibility.”

- Tools/Workflows: Export standardized responsibility summaries with each prediction; dashboards for auditors to trace decisions to components/heads; user-facing confidence with responsibility entropy.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Softmax-normalized outputs; acceptance that responsibilities are probabilistic allocations, not causal proofs; policy alignment on disclosure formats.

- Early-freeze schedules for attention (Software/ML Ops)

- Description: Exploit observed two-timescale dynamics by stabilizing attention (queries/keys) early and continuing to train values longer, improving efficiency and stability.

- Tools/Workflows: Training recipes that freeze

W_Q/W_Kafter warm-up while tuningW_Vand downstream layers; automated detection of attention stabilization via responsibility variance. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Transformer-based architectures; standard attention with softmax; monitoring to ensure performance doesn’t regress in specialized domains.

- Responsibility-weighted regularization and routing (Software/ML Ops, MoE)

- Description: Adjust learning rates or apply weight decay per component proportional to cumulative responsibility; route high-responsibility samples to specialized submodules.

- Tools/Workflows: Optimizer hooks that accumulate

r_jstatistics and modulate component updates; MoE training that uses implicit responsibilities instead of explicit gating. - Assumptions/Dependencies: LSE losses or softmax attention; training-time access to responsibilities; careful tuning to avoid reinforcing collapse.

- OOD and uncertainty heuristics using responsibility dispersion (Healthcare, Robotics, Finance, Safety)

- Description: Use responsibility entropy (or max-responsibility thresholds) to flag out-of-distribution inputs or low-certainty decisions.

- Tools/Workflows: Threshold-based alarms; triage workflows that escalate uncertain cases; sensor fusion systems that down-weight diffuse responsibilities.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Softmax normalization implies “closed world,” so rejection thresholds must be conservative; calibration needed for production use.

- Label-noise mitigation via soft supervision (Education, Healthcare, General ML)

- Description: Adopt label smoothing and soft labels as “partial responsibility clamps,” reducing overconfident misassignments and improving robustness.

- Tools/Workflows: Replace hard one-hot targets with smoothed distributions; use curriculum strategies that ramp target sharpness; integrate crowd-sourced label confidence.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cross-entropy training; datasets with noisy or uncertain labels; acceptance of slightly softer targets.

- Sensor/data-source fusion with attention responsibilities (Robotics, IoT, Autonomous systems)

- Description: Interpret attention weights as responsibilities among sensors or data streams to produce robust, interpretable fusion outputs.

- Tools/Workflows: Multi-sensor attention modules; logging of per-sensor responsibilities; health checks that detect sensor dominance or starvation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Attention-based fusion with softmax; stable calibration across sensors; safeguards against responsibility collapse.

- Objective selection guidance for multi-label tasks (Software/ML Ops)

- Description: Avoid LSE/softmax when independent predictions are required (e.g., multi-label classification); use per-class sigmoid BCE to prevent unintended competition.

- Tools/Workflows: Design checklists that flag mismatched objectives; automated linting in model repos to prevent accidental LSE in independence-required contexts.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Awareness that implicit EM requires normalization; clarity on task semantics (mutually exclusive vs independent labels).

- Responsibility-based auditing for regulated domains (Finance, Healthcare, Public Sector)

- Description: Provide structured logs of responsibility allocations per decision to meet transparency requirements and aid investigations.

- Tools/Workflows: Compliance APIs exporting per-case responsibilities; standardized reports for regulators; internal audit dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Policy acceptance of probabilistic assignment artifacts; secure storage and governance around training/inference logs.

- Regime-aware forecasting using mixture-like responsibilities (Energy, Finance)

- Description: In models that implicitly act like mixtures, use responsibility patterns to identify regime shifts (e.g., market states, weather regimes) and adjust actions.

- Tools/Workflows: Regime dashboards; automated alerts when responsibility mass migrates across components; hedging or grid-control rules tied to regime detection.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Models with LSE/softmax structures in forecasting stacks; domain-specific validation that regimes correspond to actionable states.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, or development to become robust products or standards.

- Objectives with explicit non-assignment (reject options) while preserving EM-like learning (Healthcare, Safety-critical systems, Policy)

- Description: Develop objectives that allow “none of the above” by adding null components or thresholded normalization, avoiding forced assignment.

- Tools/Products: “Open-set softmax” layers; responsibility-thresholding losses; deployment policies that combine reject options with human review.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: New loss designs and theory for stability; calibration methods; empirical validation under distributional shift.

- Volume-control terms to prevent geometric collapse (Software/ML Theory)

- Description: Introduce explicit covariance/volume penalties (e.g., log-determinant analogues or Jacobian-based regularizers) to counter EM’s positive-feedback collapse risks.

- Tools/Products: Regularization libraries with “volume” controls; analyses linking layer normalization and residual design to implicit volume.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Differentiable approximations of volume; performance trade-offs; interaction with normalization layers and scale.

- Responsibility-aware optimizers and curricula (Software/ML Ops)

- Description: Design optimizers that modulate step sizes or weight updates per component based on responsibility history; curricula that schedule competition strength.

- Tools/Products: Optimizer variants that treat

r_jas first-class signals; training planners that anneal normalization strength or temperature. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Careful convergence analysis; guardrails against runaway specialization; domain-specific tuning.

- AutoMoE: lifecycle management of components via responsibility statistics (Software/Platforms)

- Description: Automatically spawn, merge, or retire experts/heads based on sustained responsibility patterns to balance capacity and specialization.

- Tools/Products: Responsibility-driven orchestration in model servers; adaptive architecture controllers; cost-aware capacity planning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stability of responsibility estimates; robust split/merge heuristics; safeguards against fragmentation or homogenization.

- Responsibility logging standards for AI governance (Policy, Compliance, Auditing)

- Description: Establish industry norms requiring models that use softmax/LSE to log and expose responsibility allocations for transparency and recourse.

- Tools/Products: Standard schemas for responsibility logs; audit toolchains; certification processes linking logs to decisions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cross-industry agreement; privacy-preserving logging; auditor training on probabilistic assignments.

- Hardware/compilers optimized for implicit EM (Semiconductors, Systems)

- Description: Co-design forward/backward pipelines with responsibility-aware primitives; accelerate log-sum-exp and gradient normalization for EM-like workloads.

- Tools/Products: Instruction sets for stable softmax/log-sum-exp; compiler passes that fuse E-step-like forward and M-step-like backward flows.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Vendor buy-in; measurable speedups; compatibility with mainstream frameworks.

- Semi-supervised and weakly supervised frameworks as constrained responsibilities (Education, General ML)

- Description: Treat soft/partial labels as responsibility constraints, unifying semi-supervised learning with implicit EM dynamics for principled training.

- Tools/Products: APIs for responsibility constraints; adapters for crowdsourced labels; theory-backed label interpolation strategies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust methods for combining latent and clamped responsibilities; benchmarking across noisy datasets.

- Clinical decision support with calibrated responsibilities and rejection (Healthcare)

- Description: Use responsibility distributions for case triage, uncertainty communication, and safe handoffs, backed by open-set objectives.

- Tools/Products: Clinician UIs showing responsibility profiles; reject-and-escalate pipelines; monitoring of responsibility drift under domain shift.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulatory approval; rigorous calibration; integration with clinical workflows.

- Regime-switching controllers in energy/finance using responsibility dynamics (Energy, Finance)

- Description: Build controllers that adapt policies when responsibility mass shifts among latent regimes/components, enabling proactive risk management.

- Tools/Products: Policy engines tied to responsibility triggers; simulation environments to stress-test regime responses.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust mapping from responsibilities to operational decisions; safeguards against transient fluctuations.

- Extending the theory beyond LSE to broader objective classes (Academia, ML Theory)

- Description: Generalize “gradients-as-responsibilities” to other normalizing transformations or energy models; characterize when optimization equals inference.

- Tools/Products: Theoretical toolkits; benchmarks (“Bayesian wind tunnels”) for non-LSE losses; educational materials for practitioners.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: New derivations; empirical corroboration; careful scoping to avoid overreach.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- LSE structure and normalization are required for implicit EM; independent sigmoid/BCE setups won’t exhibit responsibility competition.

- Gradient-based training and differentiability are necessary to equate gradients with responsibilities; alternative optimizers won’t inherit the mechanism.

- Distance/energy interpretations of outputs must be sensible in the chosen architecture; attention and softmax classification already qualify.

- Access to training signals (gradients/responsibilities) is often needed for tooling; inference-only contexts may rely on softmax probabilities and their entropy as proxies.

- Collapse risks exist without explicit volume control; regularization, normalization, and temperature schedules are practical mitigations pending principled solutions.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.