Attention Is Not What You Need (2512.19428v1)

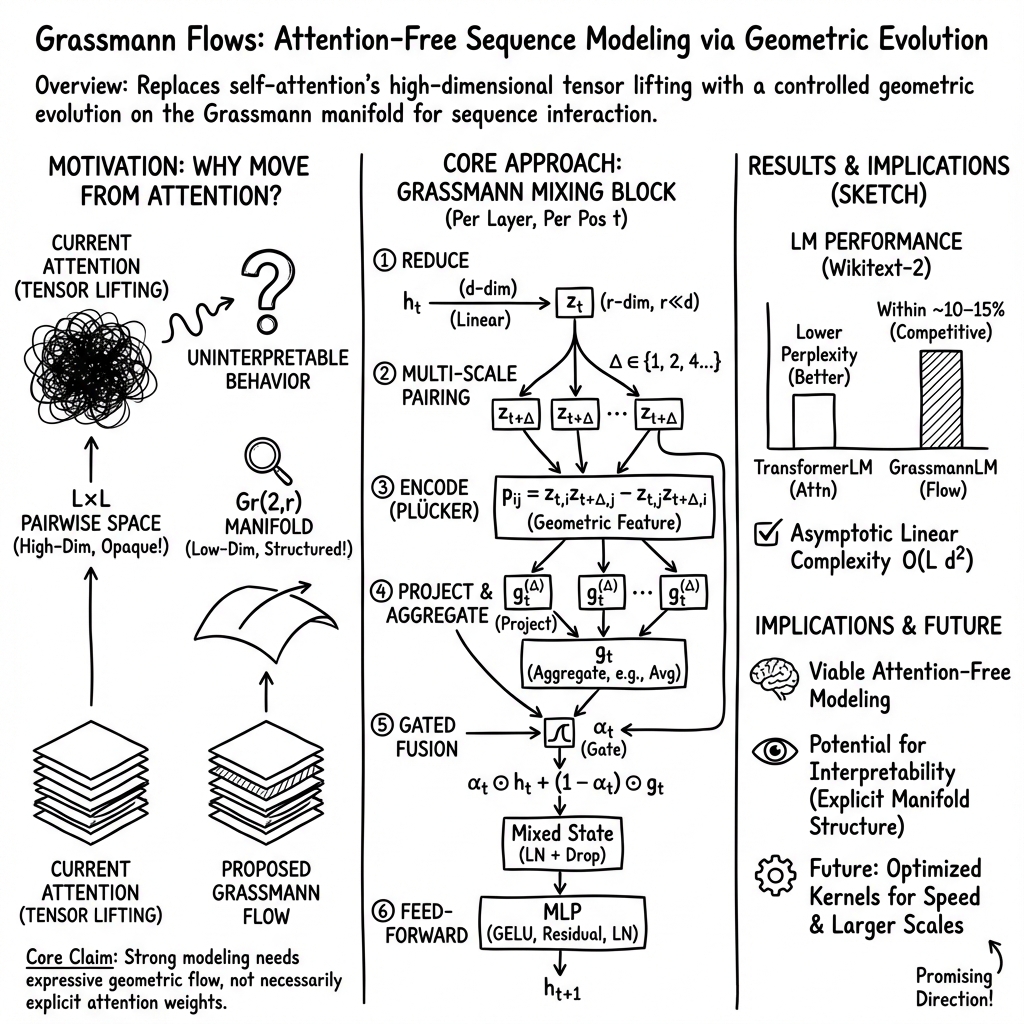

Abstract: We revisit a basic question in sequence modeling: is explicit self-attention actually necessary for strong performance and reasoning? We argue that standard multi-head attention is best seen as a form of tensor lifting: hidden vectors are mapped into a high-dimensional space of pairwise interactions, and learning proceeds by constraining this lifted tensor through gradient descent. This mechanism is extremely expressive but mathematically opaque, because after many layers it becomes very hard to describe the model with a small family of explicit invariants. To explore an alternative, we propose an attention-free architecture based on Grassmann flows. Instead of forming an L by L attention matrix, our Causal Grassmann layer (i) linearly reduces token states, (ii) encodes local token pairs as two-dimensional subspaces on a Grassmann manifold via Plucker coordinates, and (iii) fuses these geometric features back into the hidden states through gated mixing. Information therefore propagates by controlled deformations of low-rank subspaces over multi-scale local windows, so the core computation lives on a finite-dimensional manifold rather than in an unstructured tensor space. On the Wikitext-2 language modeling benchmark, purely Grassmann-based models with 13 to 18 million parameters achieve validation perplexities within about 10 to 15 percent of size-matched Transformers. On the SNLI natural language inference task, a Grassmann-Plucker head on top of DistilBERT slightly outperforms a Transformer head, with best validation and test accuracies of 0.8550 and 0.8538 compared to 0.8545 and 0.8511. We analyze the complexity of Grassmann mixing, show linear scaling in sequence length for fixed rank, and argue that such manifold-based designs offer a more structured route toward geometric and invariant-based interpretations of neural reasoning.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a bold question: do we really need “attention” (the main trick used by Transformers) to understand and model sequences like sentences? The authors say maybe not. They introduce a new, attention-free way to pass information through a sequence using geometry, called Grassmann flows. Instead of having every word look at every other word, the model uses simple local pairs of words and tracks how small “planes” in a lower-dimensional space change across layers.

What the paper is trying to find out

In simple terms, the paper explores:

- Do we truly need attention (where each token talks to all other tokens) to get good results?

- Can a model that avoids attention and uses a more structured geometric process still work well on language tasks?

- Can this new method run more efficiently as sequences get longer?

- Does this approach make models easier to understand?

How the method works (with plain analogies)

First, remember what attention does: imagine a class where every student (a word) can whisper to every other student at once. That’s powerful, but it’s chaotic and expensive—lots of whispering lines to track.

The new method limits whispering and organizes it geometrically:

- Step 1: Compress each word’s hidden vector. Think of shrinking each student’s long note into a short summary. This shorter vector has size r, which is much smaller than the original size d.

- Step 2: Use local pairs only. Each word pairs with a few nearby words (like the next one, or one a few steps away). No talking to every single word in the sentence.

- Step 3: Turn pairs into a “plane.” Take two short vectors and think of them as defining a 2D plane in the smaller space. The set of all such 2D planes lives on something called a Grassmann manifold (you can think of it as a big catalog of all possible planes).

- Step 4: Give the plane a stable ID. They use Plücker coordinates, which are just a clever way to assign consistent numbers to a plane, no matter which two vectors you used to define it. In everyday terms: different descriptions of the same plane yield the same “ID tag.”

- Step 5: Bring geometry back to the model. These IDs (features) are mapped back to the original model size and mixed with the original word vectors using a learned gate (a gate decides how much of the old info vs. new geometric info to keep).

- Step 6: Stack many layers. Repeating this “local pairs → plane → features → mix” process lets information flow across the sequence in steps, gradually covering longer ranges.

Why this is different from attention:

- Attention builds a giant matrix of who-talks-to-whom across the whole sequence (), which grows fast and is hard to analyze.

- Grassmann flow uses small, local interactions and tracks changes in a lower-dimensional, well-structured geometric space (planes), which is simpler and may be easier to understand.

A note on complexity:

- Full attention scales roughly with the square of the sequence length (like ), because every token compares with every other token.

- The Grassmann approach scales roughly linearly with sequence length (like ) for fixed settings, because each token only forms a small number of local pairs.

Main results and why they matter

The authors test their model on two tasks:

- Language modeling (Wikitext-2): The attention-free Grassmann model, with about 13–18 million parameters, gets within about 10–15% of a matched Transformer in validation perplexity. Perplexity is a score where lower is better; being close means the new method is reasonably strong even without attention. With more layers, the gap shrinks a bit.

- Natural language inference (SNLI): Using a fixed DistilBERT backbone, they replace only the classification head. The Grassmann-based head slightly beats a Transformer-style head (validation accuracy 0.8550 vs. 0.8545; test 0.8538 vs. 0.8511). The difference is small but shows the approach works in practice.

Why this is important:

- It proves competitive performance is possible without any explicit attention weights.

- It suggests we can build models that scale better with length and may be easier to analyze, because they operate on well-defined geometric objects (planes) rather than huge attention maps.

Practical note:

- Although the theory suggests good scaling, their current code isn’t yet faster in wall-clock time for moderate lengths, mainly because attention kernels on GPUs are very optimized, while the new geometric steps need tailored optimizations.

What this could mean going forward

- Rethinking “attention is essential”: This work shows attention is a choice, not a must-have. What we really need is a powerful way for information to move through a sequence—Grassmann flows are one such way.

- Better interpretability: Because the core operations live on a structured manifold (the space of planes) with known rules, it might be easier to find stable “invariants” or summaries of what the model is doing across layers, compared to juggling many attention maps.

- Efficiency for long texts: With further engineering, this approach could handle very long sequences more efficiently, since its cost grows roughly linearly with length under fixed settings.

- Future directions: Combine this geometric mixing with other ideas (like state-space models), explore higher-dimensional subspaces (not just planes), add sequence-level summary features, and build optimized kernels to speed it up.

In short: the paper argues that attention isn’t the only path to strong sequence modeling. By using geometry—specifically, tracking how small planes evolve across a sequence—the authors show we can get good results, potentially scale better, and open the door to models that are easier to understand.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, consolidated list of the paper’s concrete knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved.

- Scale and scope of evaluation: results are limited to small datasets (Wikitext-2, SNLI) and short contexts (L ≤ 256); performance on large-scale corpora (e.g., WikiText-103, PG-19, The Pile), long-context benchmarks (e.g., LRA/LongBench), and more challenging reasoning tasks is not assessed.

- Statistical reliability: the SNLI gains are very small and single-run; no multiple seeds, confidence intervals, or significance tests are reported to establish robustness of the improvement.

- End-to-end attention-free reasoning: the NLI experiments use an attention-based DistilBERT backbone with only the head replaced; the paper does not demonstrate a fully attention-free encoder for bidirectional tasks or NLI.

- Long-range dependency handling: only local, fixed offsets are used; there is no quantitative analysis of the effective receptive field across depth, nor of how dependency capture degrades as token distance increases.

- Length extrapolation: the model’s ability to generalize to much longer sequences than seen in training (with fixed r and window set m) is untested; it is unclear whether m must grow with sequence length to preserve performance.

- Baseline coverage: comparisons exclude state-of-the-art attention-free/efficient architectures (e.g., S4/SSMs, Hyena, Mamba, RetNet, RWKV, local/sparse/kernalized attention), leaving relative trade-offs in accuracy, stability, and efficiency unknown.

- Expressivity theory: there is no formal treatment of what classes of sequence interactions Grassmann flows can approximate compared to self-attention (e.g., universality, approximation error bounds, or limits induced by low-rank subspaces and local windows).

- Interpretability claims: while the paper argues Grassmann flows are more amenable to invariants, it does not define, compute, or analyze any concrete invariants (e.g., cross-layer stability metrics, curvature-like quantities) nor show how they relate to behavior.

- k=2 restriction: only 2D subspaces are used; the benefits, costs, and training stability of higher-dimensional subspaces (), mixtures of k, or adaptive k are not explored.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity: there is no systematic ablation of reduced dimension r, window set m, window schedules, or gating architecture; sensitivity curves and best-practice ranges are missing.

- Window design: offsets are hand-crafted and static; it remains unknown whether learned/content-conditioned/dilated or adaptive windows improve performance or efficiency.

- Multi-head Grassmann mixing: the LM variant appears single-headed; the effect of multiple Grassmann “heads” (e.g., subspace groups or r-partitioning) on performance and stability is not studied.

- Numerical stability near degeneracy: when paired vectors are nearly colinear or low-norm, Plücker vectors approach zero; normalization with ε is ad hoc and its impact on gradients, training stability, and sensitivity is unquantified.

- Orientation and order effects: the wedge product is orientation-sensitive and depends on the ordered pair (z_t, z_{t+Δ}); the consequences of this asymmetry (beneficial for causality vs. brittle to reordering) are not examined; alternatives (e.g., symmetric features, |p|, or sign-invariant encodings) are not evaluated.

- Alternative Grassmann parameterizations: other coordinate systems (e.g., orthonormal frames, projection matrices, principal angles) may offer better numerical stability or efficiency; no comparison is provided.

- Manifold fidelity and constraints: while Plücker vectors are computed from z (ensuring validity), there are no regularizers or diagnostics to maintain smoothness of subspace trajectories across layers or to enforce geometric priors beyond local pairing.

- Reduction map design: W_red is unconstrained; whether orthonormal, unitary, or structured reductions preserve more useful subspace geometry (and improve stability/interpretability) is not explored.

- Complexity trade-offs in practice: despite theoretical O(L) in sequence length for fixed r and m, the layer retains O(L d2) costs from gating/FFN, and the implementation is slower than attention; there is no profiling of throughput/latency/memory vs. L, r, m, d nor guidance on regimes where Grassmann wins.

- Memory footprint: storing Plücker features for all positions and windows during backprop may be costly; peak memory and activation checkpointing strategies are not analyzed.

- Parameter and compute scaling: the size of W_plu scales with d·(r choose 2); limits on r (and k) from compute/memory constraints are not quantified, and scaling laws with model size/depth are absent.

- Training depth and stability: experiments stop at 12 layers; behavior at greater depths (e.g., 24–48+), gradient stability, and the interaction of layer norm, gating, and Plücker normalization are unreported.

- Bidirectional modeling: only causal LM is implemented; extensions to bidirectional encoders (e.g., masked LM) and how to incorporate both left/right contexts in the Grassmann framework are not demonstrated.

- Domain generality: the approach is not tested beyond text (e.g., vision, audio, multivariate time series), leaving cross-domain applicability and necessary adaptations unknown.

- Robustness and OOD behavior: sensitivity to noise, perturbations, adversarial inputs, domain shift, and cross-lingual generalization is not evaluated.

- Diagnostic tasks: no targeted probes (e.g., Copy/Reverse/Add, subject-verb agreement, long-range bracket matching) are used to identify failure modes or characterize what dependencies Grassmann flows capture or miss.

- Fair-tuning and reproducibility: hyperparameter tuning parity with the Transformer baseline is unclear; optimizer specifics, seeds, and training variance are not provided to enable rigorous replication and comparison.

- Integration with complementary modules: hybrids with SSMs, convolution, or retrieval/memory (suggested in discussion) are not prototyped, leaving practical design questions (interfaces, stability, training) open.

- Global/sequence-level signals: the paper proposes sequence-level invariants as a future direction but does not implement or measure whether injecting such global summaries improves long-range reasoning or calibration.

- Calibration and uncertainty: only perplexity/accuracy are reported; model calibration, confidence quality, and error types are not analyzed.

- Tokenization and representation effects: the interaction between subword tokenization and low-dimensional reduction (information loss, morphology) is not studied.

These gaps outline concrete directions for future work, including controlled ablations (r, m, k), more rigorous baselines and statistics, theoretical expressivity/interpretability analyses, numerical engineering, and evaluations on larger, longer, and more diverse benchmarks.

Glossary

- Algebraic variety: A set of points satisfying polynomial equations; here, the Plücker-embedded Grassmannian subset of a coordinate space. "it is an algebraic variety defined by the quadratic Pl\"ucker relations."

- Asymptotic complexity: The growth rate of computational cost as input size increases. "We analyze the asymptotic complexity of Grassmann mixing and show that, for fixed rank and window sizes, it scales linearly in sequence length"

- Causal Grassmann architecture: The proposed attention-free sequence model that mixes representations via flows on a Grassmann manifold using causal windows. "We evaluate this Causal Grassmann architecture on language modeling (Wikitext-2) and natural language inference (SNLI)."

- DistilBERT: A compact, distilled version of BERT used as a backbone encoder. "we fix a DistilBERT-base-uncased backbone as a feature extractor."

- Exterior power: The vector space constructed from antisymmetric k-linear combinations of vectors; denoted Λk of a vector space. "in the -th exterior power ."

- Exterior product: The antisymmetric product (wedge) of vectors that represents a k-dimensional oriented volume element. "we form the exterior product "

- Fisher information: A Riemannian metric on statistical manifolds that measures the amount of information a random variable carries about a parameter. "local metrics (e.g., Fisher information)"

- Gated mixing block: A learnable mechanism that fuses Grassmann-derived features back into hidden states via gates. "fuse the resulting geometric features back into the hidden states through a gated mixing block."

- GELU: Gaussian Error Linear Unit, an activation function commonly used in Transformers. "and a nonlinearity (we use GELU)."

- Grassmann flow: The evolution of subspace representations across layers when operating on a Grassmann manifold. "We refer to the resulting architecture as a Causal Grassmann model or Grassmann flow."

- Grassmann manifold (Grassmannian): The set of all k-dimensional linear subspaces of a vector space. "The Grassmann manifold is the set of all -dimensional linear subspaces of ."

- Hyperbolic manifolds: Spaces of constant negative curvature often used for hierarchical representations. "including hyperbolic, spherical, and other Riemannian manifolds."

- Information geometry: The study of geometric structures (like metrics and curvature) on spaces of probability distributions. "the interplay between local and global structures in information geometry"

- Kernelized attention: An attention formulation that uses kernel methods to approximate dot-product attention more efficiently. "including linearized or kernelized attention"

- Layer normalization: A technique that normalizes activations across feature dimensions within a layer. "followed by a layer normalization and dropout:"

- Linear dynamical systems: Models in which the latent state evolves linearly over time, often used in control and signal processing. "interpret sequences as signals governed by linear dynamical systems"

- Linearized attention: Approximations to softmax attention that make computation linear in sequence length. "including linearized or kernelized attention"

- Low-rank approximation: Representing a matrix or operator with lower rank to reduce complexity while retaining key structure. "such as subspace clustering, low-rank approximation, and metric learning"

- Metric learning: Learning distance functions or embeddings that capture task-relevant similarities. "such as subspace clustering, low-rank approximation, and metric learning"

- Minor (matrix minor): The determinant of a k×k submatrix, used here to define Plücker coordinates. "whose entries are the minors of the matrix ."

- Multi-scale windows: A set of local context offsets at different sizes used to capture information at multiple ranges. "We define a set of window sizes (offsets) , e.g., "

- Perplexity: An evaluation metric for LLMs measuring predictive uncertainty; lower is better. "best validation perplexity of 261.1"

- Plücker coordinates: Coordinates of a subspace obtained from the determinants (minors) of a basis matrix, representing points on the Grassmannian in projective space. "embed these subspaces via Pl\"ucker coordinates into a finite-dimensional projective space"

- Plücker embedding: The map that sends a k-dimensional subspace to a point in projective space via its exterior product. "We use the Pl\"ucker embedding, which maps each -dimensional subspace to a point in projective space:"

- Plücker relations: Quadratic algebraic constraints that characterize which coordinate vectors correspond to actual subspaces under the Plücker embedding. "it is an algebraic variety defined by the quadratic Pl\"ucker relations."

- Plücker vector: The coordinate vector (in Λk space) representing a subspace under the Plücker embedding. "we form the Pl\"ucker vector $p_t^{(\Delta)} \in \mathbb{R}^{\binom{r}{2}$"

- Projective space: A space of lines through the origin (equivalence classes up to scale), used to host Plücker-embedded subspaces. "to a point in projective space:"

- Residual connection: A skip connection that adds a layer’s input to its output to improve optimization and stability. "Another residual connection and layer normalization complete the layer:"

- Semantic manifold: A conceptual manifold on which hidden states live, capturing semantic geometry of representations. "Hidden states of a LLM can be seen as points on a high-dimensional semantic manifold."

- State-space models: Sequence models based on latent states evolving through time according to system equations. "State-space models and related architectures interpret sequences as signals governed by linear dynamical systems"

- Subspace clustering: Grouping data according to low-dimensional subspaces they lie in, rather than around point centroids. "such as subspace clustering, low-rank approximation, and metric learning"

- Tensor lifting: Mapping vectors to higher-order tensor spaces to capture interactions (e.g., pairwise) before processing. "We reinterpret self-attention as a particular instance of tensor lifting"

- Universal approximation theorems: Results guaranteeing that neural networks can approximate broad classes of functions/operators given sufficient capacity. "Classic universal approximation theorems tell us that neural networks can approximate such operators"

- WordPiece: A subword tokenization method that builds a vocabulary of frequent word pieces. "We use a WordPiece-like vocabulary of size "

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed with current methods and modest engineering, leveraging the paper’s Grassmann flow mechanisms and empirical results on Wikitext-2 and SNLI.

- Bold application titles below are followed by sector tags and a brief description of tools/workflows and assumptions or dependencies.

- Drop-in Grassmann classification head for sentence-pair tasks (SNLI-like) (industry: NLP products; academia)

- Use case: Replace Transformer-based classification heads on existing Transformer backbones (e.g., DistilBERT) with a Grassmann–Plücker head to slightly boost accuracy on natural language inference, contradiction detection, and entailment tasks in customer support, contract analysis, and content moderation.

- Tools/workflows: PyTorch module implementing linear reduction, local windows, Plücker embedding, gated fusion, and FFN; fine-tuning on task datasets; integration into existing inference pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Gains are modest; relies on a competent pretrained backbone. Hyperparameters (reduced rank r, window schedule) need light tuning; no specialized kernels required.

- Geometric interpretability probes for model debugging (industry: ML engineering; academia)

- Use case: Instrument models to log and analyze Plücker coordinates and Grassmann subspace trajectories across layers/windows, yielding compact geometric descriptors of representation dynamics for audits, ablations, and failure-mode discovery.

- Tools/workflows: Lightweight logging hooks; metrics like subspace stability across layers, dispersion of Plücker vectors, locality sensitivity; visualization dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Correlation between geometric invariants and task behavior must be empirically validated per domain; added logging overhead should be budgeted.

- Attention-free sequence heads in compliance-sensitive NLP (industry: finance, healthcare, legal)

- Use case: Deploy attention-free heads where interpretability requirements favor finite-dimensional, structured computations over opaque attention tensors. Applicable to document labeling, triage, and entity-linking tasks with short-to-medium sequences.

- Tools/workflows: Swap-in Grassmann mixing layers in classification/ranking heads; generate geometric summaries (e.g., subspace stability reports) alongside predictions for audit trails.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulators or internal risk teams must accept geometric metrics as meaningful proxies; performance is close to Transformer heads but not guaranteed superior on all tasks.

- Curriculum and research training on manifold-based sequence modeling (academia; education)

- Use case: Course modules, workshops, and reproducibility exercises demonstrating Grassmann flows as an alternative to attention, including hands-on labs with Wikitext-2 and SNLI.

- Tools/workflows: Teaching notebooks; open-source implementations; assignments to design window schedules and interpret Plücker features.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of open-source code and moderate compute; conceptual emphasis on geometry aligns with program goals.

- Cost modeling and architectural benchmarking without attention (software/ML infrastructure)

- Use case: Benchmark Grassmann mixing vs. attention under application-specific constraints (short to medium sequence lengths), and plan for cases where linear-in-L asymptotics may be advantageous as contexts grow.

- Tools/workflows: Profiling scripts; comparative experiments varying L, r, and window schedules; integration with MLOps dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Current implementations may be slower per step due to non-optimized kernels; results are most informative for planning future migrations or hybrid designs.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, engineering (e.g., fused kernels or hardware support), and validation before broad deployment.

- Long-context, attention-free document and code modeling with linear scaling (software; enterprise document AI; developer tools)

- Use case: Process very long sequences (legal contracts, logs, source code, scientific articles) with near-linear complexity, enabling on-device or cost-efficient cloud inference.

- Tools/products/workflows: Fused CUDA kernels for Plücker computation and projection; optimized GPU/TPU ops; training recipes for deeper models and higher r; sequence-level global invariants (e.g., curvature-like measures, averaged subspaces) to capture non-local dependencies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Engineering of high-performance kernels; empirical parity or advantage vs. attention on long-context tasks; robustness with higher-dimensional subspaces (k > 2); stable training at scale.

- Geometric interpretability suites and certifiable AI behavior (policy/regulation; healthcare; finance)

- Use case: Standardize geometric invariants (stability of subspaces across layers, trajectory curvature, global Grassmann summaries) as audit-ready explanations of model behavior; support compliance certifications (e.g., transparency, robustness).

- Tools/products/workflows: Model auditing toolkits that compute and report invariants; governance workflows aligning geometric metrics with domain risks; documentation templates for regulators.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consensus in academia/industry that these invariants correlate with safety/performance; standards development; acceptance by regulators; domain mapping from geometric descriptors to human-understandable explanations.

- Energy-efficient on-device assistants and IoT NLP (energy; mobile; daily life)

- Use case: Battery-friendly voice/text assistants and wearables leveraging linear scaling for longer inputs without quadratic attention costs.

- Tools/products/workflows: Mobile inference libraries with Grassmann kernels; quantization-aware training; adaptive window schedules tuned to device constraints; fallbacks to hybrid attention for rare long-range dependencies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware-accelerated implementations; comparable accuracy to attention-based models; careful UX for edge cases requiring global context.

- Hybrid SSM + Grassmann architectures for temporal reasoning (robotics; speech; time-series forecasting; finance)

- Use case: Combine structured dynamical systems (state-space models) for temporal evolution with Grassmann constraints on representation geometry, improving stability and long-range reasoning in control, forecasting, and ASR.

- Tools/products/workflows: Library components integrating SSM kernels with Grassmann mixing; training curricula for multi-modal data; deployment in control loops and production forecasting pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Demonstrated gains over SSM-only or attention-based baselines; reliable training dynamics; domain-specific feature engineering.

- Hardware co-design (ASIC/TPU) for Grassmann ops (semiconductors; cloud providers)

- Use case: Instruction sets and accelerators optimized for wedge products, Plücker embeddings, and gated fusion—reducing latency and energy for attention-free sequence models.

- Tools/products/workflows: Compiler support for new primitives; benchmarking suites; co-designed kernels in major frameworks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Economic viability; ecosystem adoption; long-term stability of Grassmann primitives in mainstream models.

- Domain extensions beyond language: bioinformatics, cybersecurity, and network analytics (healthcare/genomics; security; telecom)

- Use case: Model protein/DNA sequences, anomaly patterns in network traffic, and intrusion detection logs via local subspace geometry, with interpretability benefits (e.g., motif-like invariants).

- Tools/products/workflows: Domain adapters mapping tokens to reduced spaces; invariant dashboards tailored to domain semantics; training on large specialized corpora.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Empirical validation that Grassmann features capture relevant biological or security structures; scale-up of datasets; domain partnerships.

- Personal knowledge management and visualization of “semantic geometry” (daily life; productivity tools; education)

- Use case: Visualize how ideas evolve across notes or documents via trajectories on Grassmann manifolds—supporting learning analytics and personal research tooling.

- Tools/products/workflows: UX components rendering subspace evolution; summarization via global invariants; integrations with note-taking apps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accessible mappings from geometric descriptors to user-understandable insights; privacy-preserving on-device processing.

- Framework-level support and model zoo for Grassmann flows (software/ML infrastructure)

- Use case: First-class Grassmann layers in PyTorch/TF/JAX; pretrained attention-free or hybrid checkpoints; standardized APIs for window schedules and invariants.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open-source libraries; training scripts; evaluation harnesses; community benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sustained community interest; comparative performance on mainstream tasks; maintenance and documentation.

- Policy guidance moving beyond attention-weight explanations (policy; governance)

- Use case: Advisory papers and best practices that recognize the limits of attention-weight interpretability and propose manifold-based metrics for transparency in AI systems.

- Tools/products/workflows: Policy toolkits; regulator workshops; cross-industry working groups to define acceptable geometric proxies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interdisciplinary agreement; demonstrated practical utility; alignment with emerging AI governance frameworks.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.