World Models Can Leverage Human Videos for Dexterous Manipulation (2512.13644v1)

Abstract: Dexterous manipulation is challenging because it requires understanding how subtle hand motion influences the environment through contact with objects. We introduce DexWM, a Dexterous Manipulation World Model that predicts the next latent state of the environment conditioned on past states and dexterous actions. To overcome the scarcity of dexterous manipulation datasets, DexWM is trained on over 900 hours of human and non-dexterous robot videos. To enable fine-grained dexterity, we find that predicting visual features alone is insufficient; therefore, we introduce an auxiliary hand consistency loss that enforces accurate hand configurations. DexWM outperforms prior world models conditioned on text, navigation, and full-body actions, achieving more accurate predictions of future states. DexWM also demonstrates strong zero-shot generalization to unseen manipulation skills when deployed on a Franka Panda arm equipped with an Allegro gripper, outperforming Diffusion Policy by over 50% on average in grasping, placing, and reaching tasks.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching robots with hand-like grippers (robot hands with fingers) to handle objects in a smart, careful way—more like humans do. The authors build a “world model” called DexWM that learns from hours of human videos and robot videos to predict what will happen next when a hand moves and touches objects. Using this model, a robot can plan its actions to reach, grasp, and place items, even in new situations it hasn’t been trained on.

Goals

The researchers set out to answer simple, practical questions:

- Can a robot learn fine, finger-level skills by watching human videos?

- What’s the best way to describe “actions” for a robot hand (not just “move the wrist,” but how each finger changes)?

- Will a special training trick that keeps hand positions accurate improve results?

- Can the model trained on human videos work “zero-shot” (without extra training) on real robots for tasks like grasping?

How It Works (Methods)

Think of DexWM as the robot’s “imagination.” It imagines the future—what the hands and objects will look like—based on what it sees and what it plans to do next.

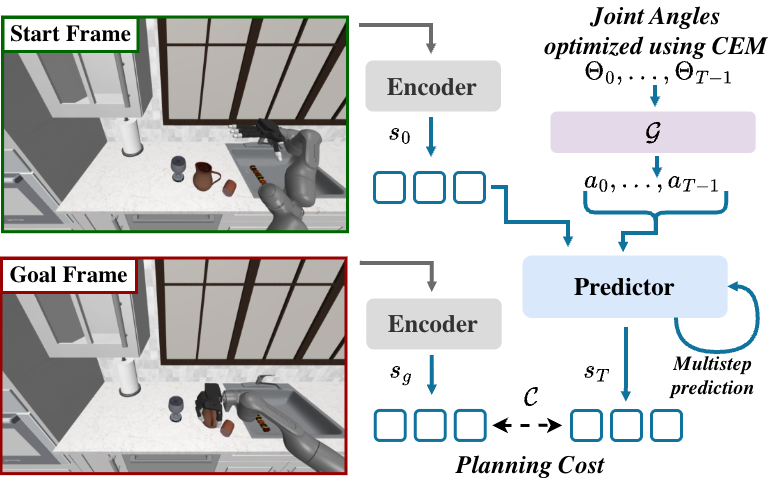

- World model: This is like a mental simulator. Give it the current scene and a hand action, and it predicts the next scene.

- Latent state: Instead of looking at every pixel, the model compresses each image into a compact summary (a “latent state”) that captures important things like shapes and positions.

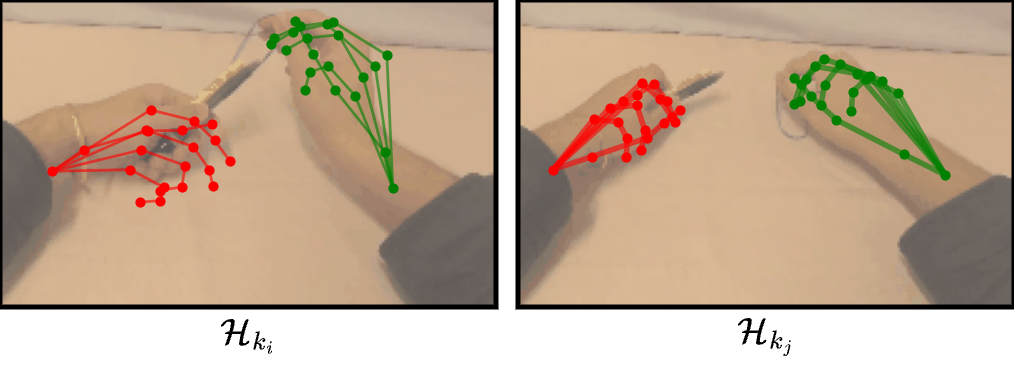

- Actions as hand keypoints: Actions are written as changes in the 3D positions of tiny “dots” on the hands (keypoints on each finger and the wrist). This is like marking important points on your hand and tracking how they move frame by frame. The model also includes how the camera moves (so it knows if the viewpoint changed).

- Predictor network: A transformer (a kind of smart pattern-finding neural network) takes the recent scene summaries and the hand action, then predicts the next scene summary.

- Hand consistency loss: During training, the model doesn’t just try to predict the next scene summary—it also tries to get fingertip and wrist locations right by predicting heatmaps (bright spots where fingers should be). This extra “hand accuracy” push helps the model learn fine-grained dexterity.

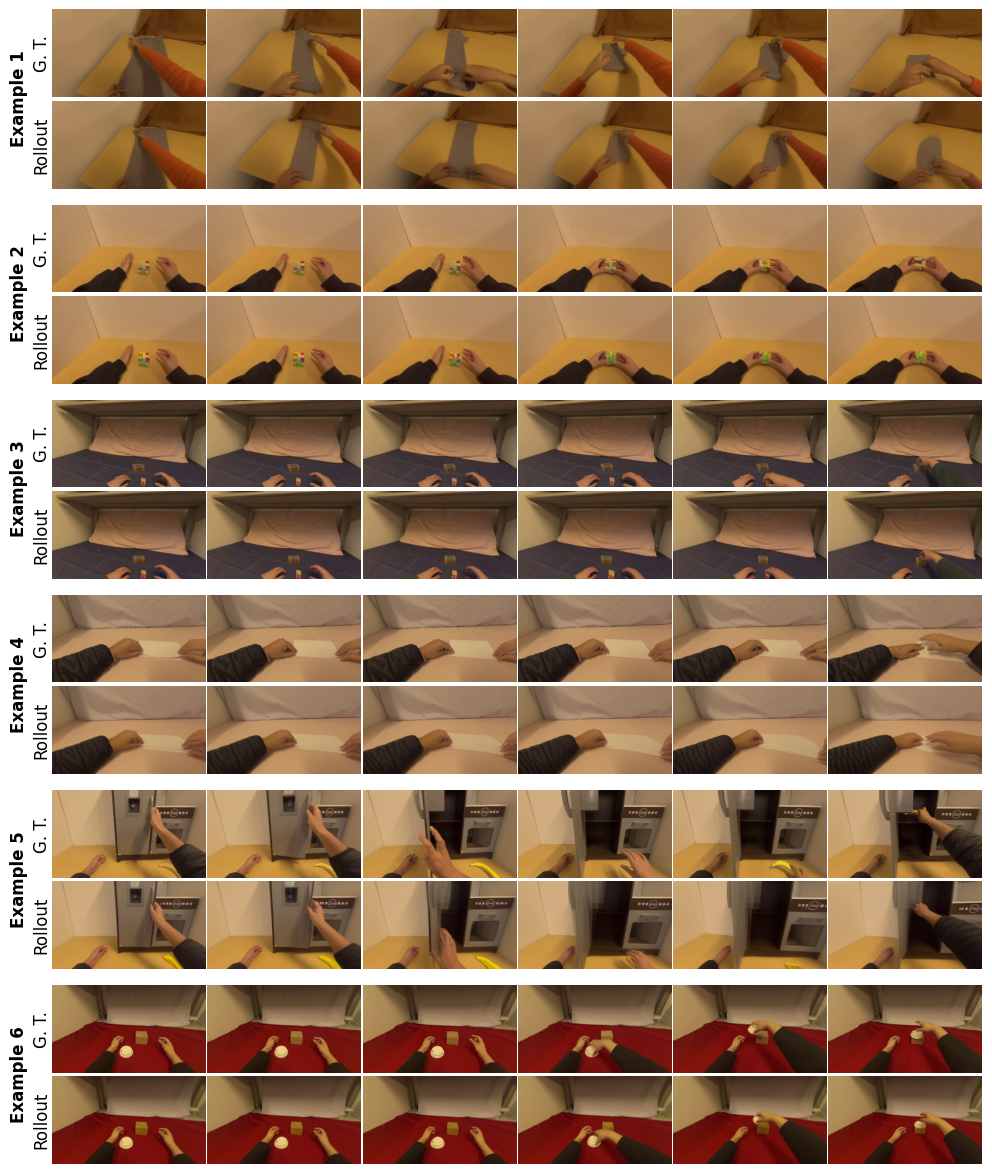

- Training data: About 900 hours of videos—mostly egocentric human videos (where the camera sees what a person sees) plus robot videos—teach the model general manipulation skills. Then, the model is lightly fine-tuned on about 4 hours of simple, exploratory robot motion in simulation (no detailed task labels).

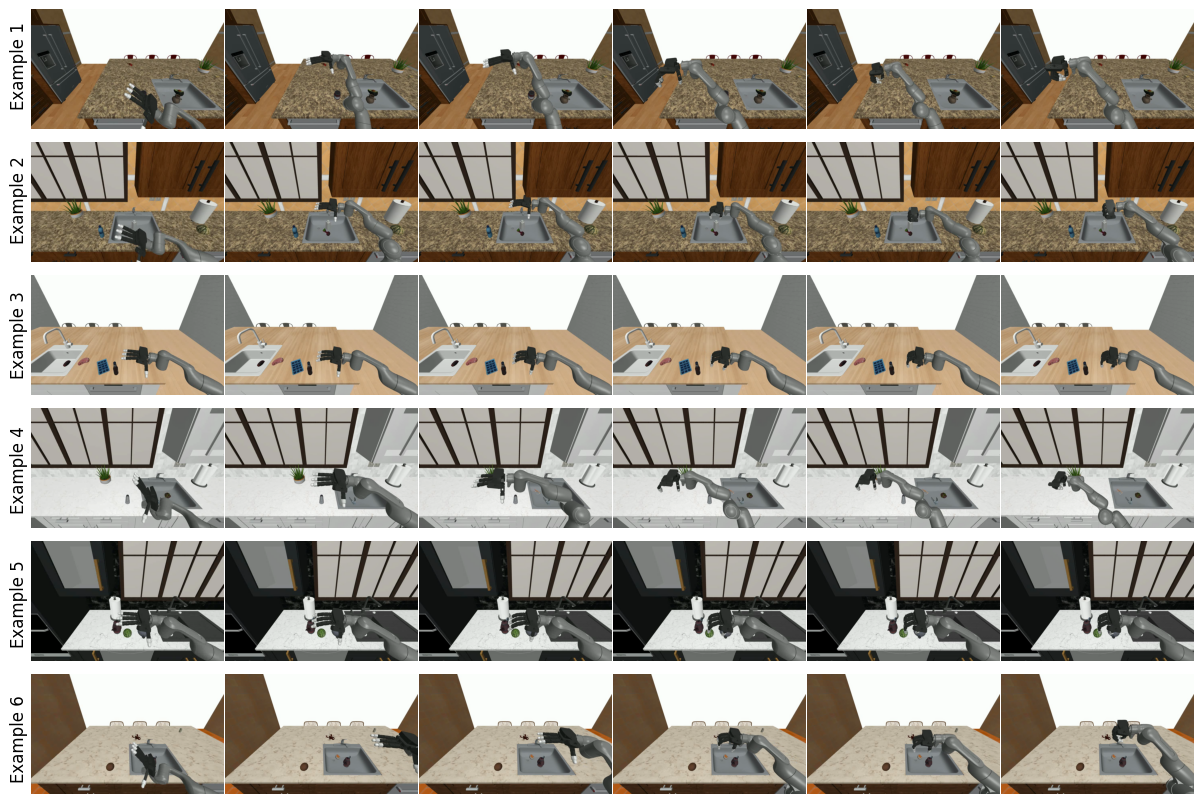

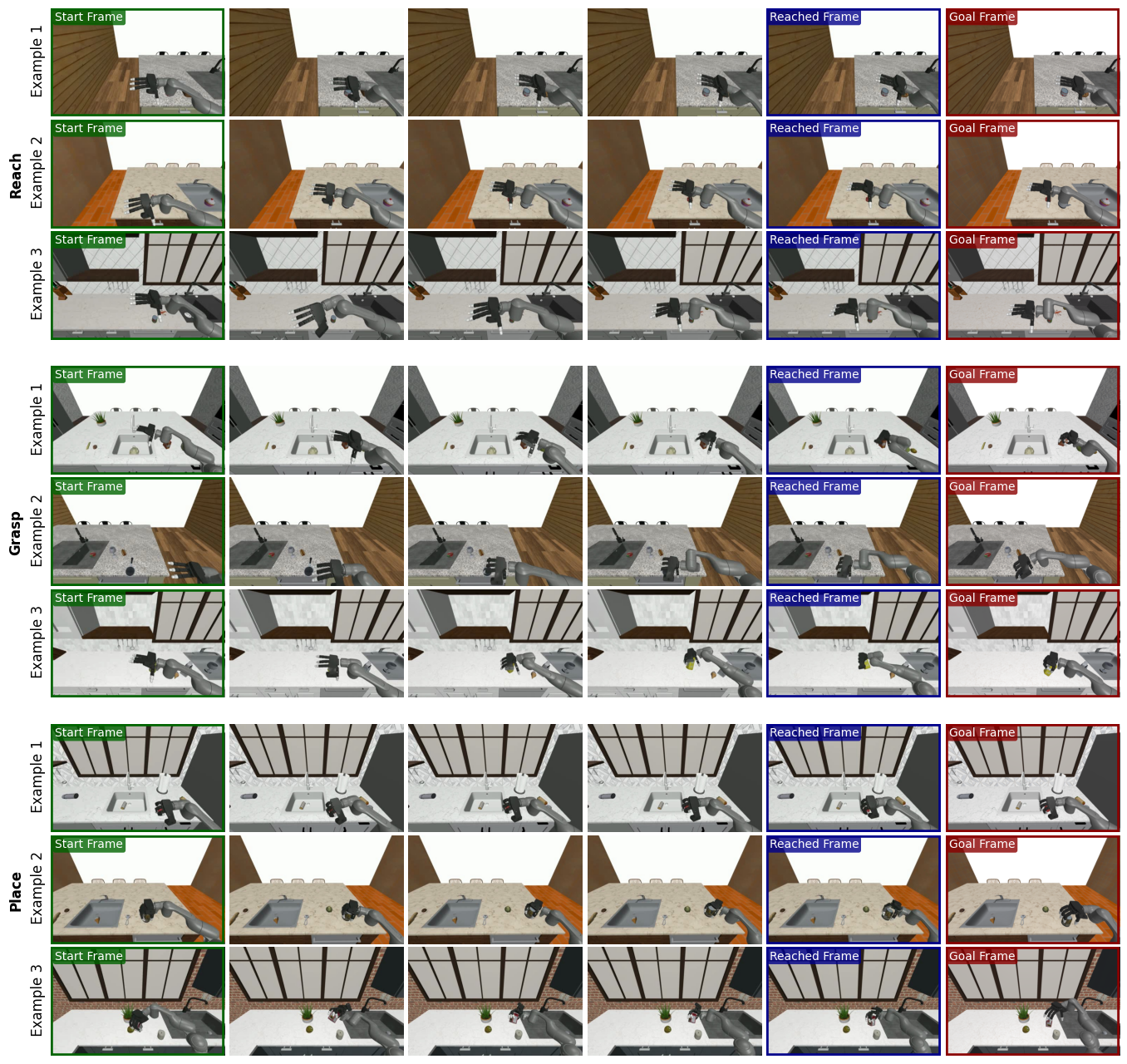

- Planning at test time: Instead of directly outputting actions, the robot uses the world model to plan. It tries many possible joint movements (using a method called CEM, which is like smart trial-and-error), simulates the future using DexWM, and picks the action sequence that gets closest to a goal image and accurate hand positions. This is known as MPC (Model Predictive Control)—plan, test in imagination, pick the best, execute.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here are the key results and their importance:

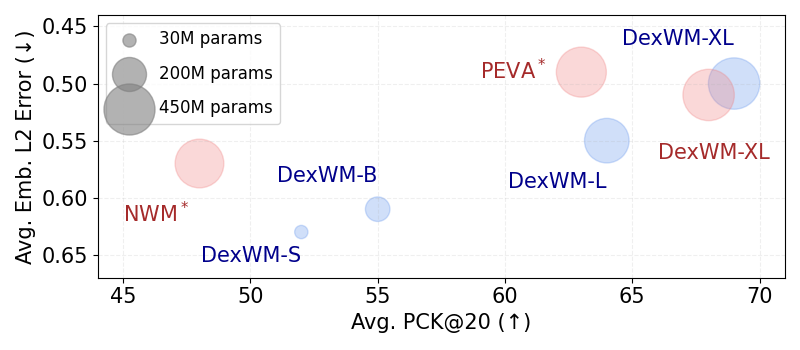

- Better predictions: DexWM predicts future scenes and hand positions more accurately than other world models that use text commands or whole-body motion but don’t focus on fingers. This matters because finger accuracy is critical for precise manipulation.

- The hand consistency loss helps a lot: Adding the hand accuracy training increased correct finger-location matches by up to 34% in longer rollouts. This shows the model truly learned fine hand control, not just overall scene appearance.

- Human videos help robots: Training on human videos boosts performance in robot simulations and transfers skills across different “bodies” (from human hands to robot hands). This is powerful because high-quality robot hand data is rare.

- Scales with model size: Bigger versions of DexWM get better, suggesting that more capacity improves understanding of complex hand-object interactions.

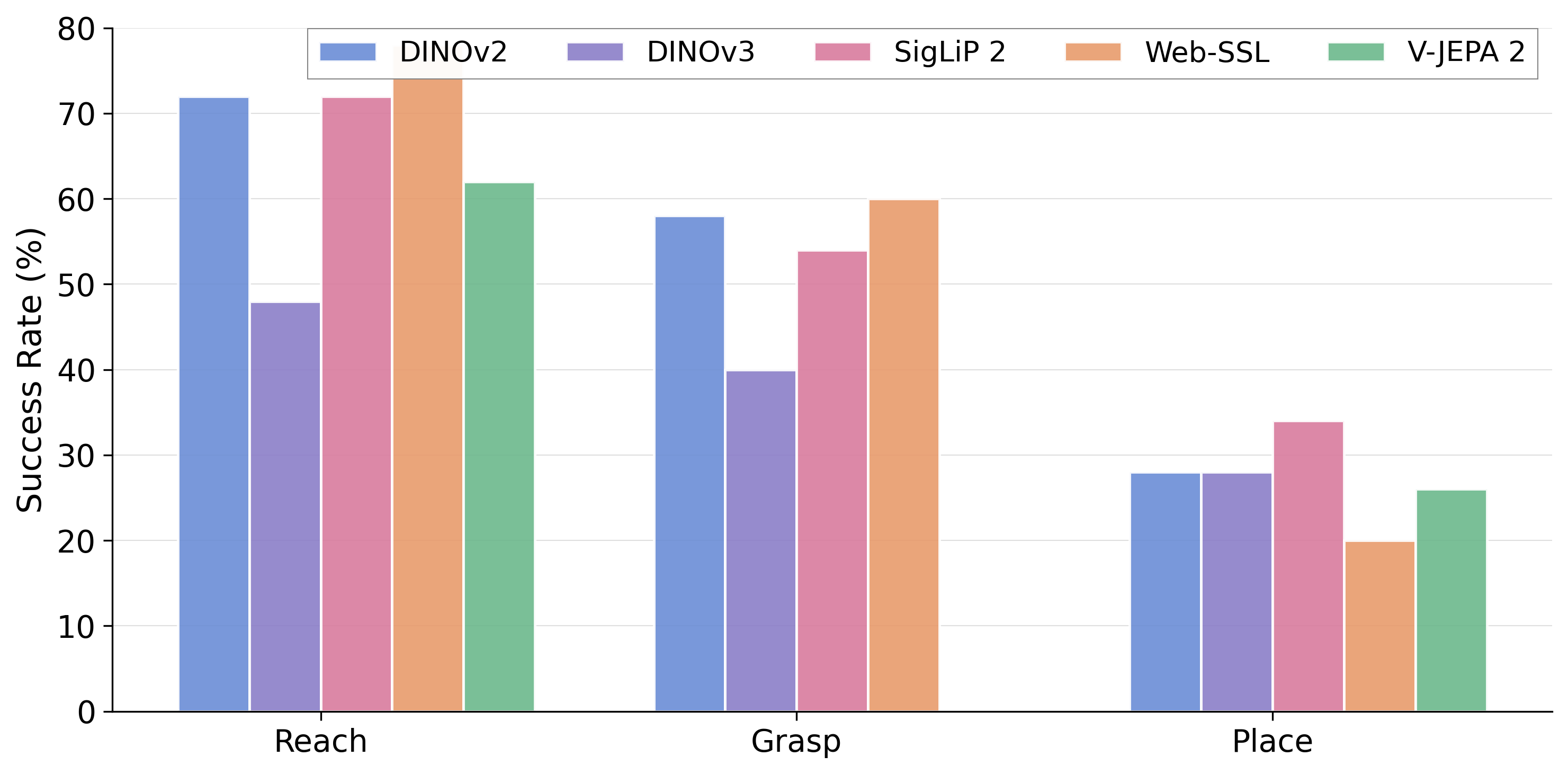

- Works with different vision backbones: DexWM can use various visual encoders, though DINOv2 was best overall in their tests.

- Strong zero-shot performance on real robots: On a Franka Panda arm with an Allegro hand, DexWM achieved about 83% success in grasping objects without any real-world training—only the 4 hours of exploratory simulation fine-tuning. In simulation, it succeeded in:

- 72% of reach tasks

- 58% of grasp tasks

- 28% of place tasks

- Outperforms a popular baseline: DexWM beat Diffusion Policy by over 50% on average across tasks, especially because DexWM plans using its learned “world” rather than relying on direct action predictions from data that didn’t include successful task examples.

Implications

This work suggests a simple but powerful idea: robots can learn dexterous manipulation by watching humans. A good world model can:

- Bridge the data gap when robot-hand videos are limited.

- Give robots a reliable “simulator in their head” to plan before acting.

- Make zero-shot transfer possible—getting strong real-world results without extensive new training.

Looking ahead, the authors note that planning longer tasks could be faster and more efficient with better planners, and the model could be extended to use text goals (“put the mug on the shelf”), not just image goals. Overall, this approach is a step toward flexible, general-purpose robot hands that can adapt to new objects and tasks like we do.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a concise list of concrete knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper. Each item is framed to enable actionable follow-up work.

- Long-horizon planning: The approach requires subgoals for multi-step tasks (e.g., pick-and-place). How to endow DexWM with hierarchical prediction or options to plan from scratch over long horizons without manual subgoaling?

- Planning efficiency: Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) is slow and sample-inefficient. Can first-order, gradient-based MPC or learned planners significantly reduce planning time while maintaining success rates?

- Uncertainty modeling: The predictor is deterministic, despite inherently multi-modal futures in contact-rich manipulation. How would stochastic or ensemble world models affect planning robustness, safety, and success?

- Contact and physics fidelity: Demonstrations show simple interactions (e.g., pushing a cup), but there is no quantitative evaluation of contact dynamics, friction, compliance, or stability. Can the model learn and exploit richer physics (e.g., stick–slip, deformable objects, tool use)?

- Sensor modalities: The model uses only RGB and keypoints; there is no depth, tactile, force/torque, or proprioceptive feedback. How much would multimodal sensing improve dexterous control and sim-to-real transfer?

- 3D representation: The state is 2D patch features; hand consistency is trained via 2D heatmaps for fingertips/wrists only. Can explicit 3D states (e.g., NeRFs, SDFs, point clouds) or full 21-keypoint 3D supervision improve occlusion handling and precision in hand–object contacts?

- Keypoint coverage: The auxiliary loss supervises only fingertips and wrists (12 channels). Does including full phalange keypoints (all 21 per hand) or contact points improve fine manipulation and in-hand control?

- Annotation and pose noise: The approach assumes accurate 3D hand keypoints and camera egomotion (T, δt, δq). How sensitive is performance to noise, bias, or drift in these estimates, and can self-supervised or robust objectives mitigate this dependence?

- Camera egomotion requirement: Training and action encoding assume known camera motion; estimation quality is undeclared for real deployments. How to estimate egomotion reliably in general settings (e.g., moving cameras) and how robust is DexWM to egomotion errors?

- Embodiment gap: Transfer is shown on one platform (Franka + Allegro). How well does the method generalize across different arms, grippers, and kinematic/dynamic properties without re-training or with minimal adaptation?

- Dummy keypoints for non-dexterous data: DROID actions are approximated by dummy hand keypoints. What is the quantitative impact of this approximation on learned dynamics and transfer, and can better proxy representations reduce the gap?

- Data scaling and composition: The paper shows model-size scaling but not data-scaling laws. What is the effect of more human video hours, different human–robot data ratios, or curriculum schedules on downstream success?

- Fine-tuning strategy: The model is fine-tuned on ~4 hours of exploratory sim data. What is the minimal amount and type of robot data needed for strong sim-to-real transfer, and how do different exploration strategies affect outcomes?

- Encoder freezing: The image encoder (e.g., DINOv2) is frozen. Would joint fine-tuning or adapter-based tuning on robot data yield better alignment of the latent space to dexterous control?

- Goal specification: Planning is evaluated with image goals; text or semantic goal conditioning is not implemented. How to define and align semantic goals (e.g., language, affordances) with latent planning costs?

- Planning cost shaping: The cost is a weighted sum of latent L2 and keypoint distance. How sensitive are results to cost weights, and can learned cost/reward models (or contact-aware costs) improve performance?

- Constraint handling: MPC does not explicitly enforce joint limits, self-collision, environment collisions, or safety constraints. How to integrate hard constraints or safety layers into the optimizer?

- Real-time performance: The paper does not report planning latency or control frequency. Can the method meet real-time constraints on embedded hardware for closed-loop control?

- Closed-loop control details: MPC frequency, re-planning cadence, and observation feedback handling are under-specified. How does success depend on re-planning rate and feedback latency, and how resilient is the method to model error accumulation?

- Robustness to domain shift: Generalization to lighting changes, clutter, occlusions, camera intrinsics, and novel object geometries is not systematically evaluated. What is the robustness envelope and how to expand it?

- Task breadth: Demonstrations focus on reaching, grasping, and placing; no in-hand manipulation or tool-use benchmarks are reported. Can DexWM scale to complex dexterous tasks requiring finger gaiting, regrasping, and precise force control?

- Baseline coverage: Comparisons omit recent closed-loop world-model RL methods, strong VLA planners, or policy priors trained on task successes. How does DexWM fare against these alternatives under matched data and embodiment conditions?

- Metric validity: Open-loop embedding L2 and PCK@20 are used as surrogates. What metrics better predict downstream manipulation success (e.g., contact accuracy, object pose error, success-on-simulation tasks)?

- Action space choice: Actions are hand keypoint deltas plus egomotion. Are there more controllable or robot-agnostic action parameterizations (e.g., contact-centric actions, object-centric frames) that improve transfer and optimization?

- Autonomy vs. supervision: The method assumes access to hand keypoints in human videos. Can self-supervised hand/object pose estimation or weak labels replace manual/expensive annotations at scale?

- Safety and reliability: There is no assessment of failure modes, unsafe behaviors, or recovery strategies under perception or actuation faults. How to certify safe exploration and planning with learned world models?

- Multi-view/multi-camera setups: The approach is egocentric-only. Would multi-view training and inference improve 3D consistency and reduce occlusion failures?

- Adaptation online: No online model adaptation or residual learning is used during deployment. Can lightweight online updates or meta-learning improve robustness in the real world?

- Articulated and deformable objects: Transfer to articulated mechanisms and deformables is not evaluated. How to extend DexWM to these object classes and measure performance systematically?

- Hyperparameter sensitivity: The hand consistency weight λ=100 is reported “best” but without sensitivity analysis. What is the stability of performance across λ and other critical hyperparameters?

- Time discretization: Training uses randomly skipped frames; deployment assumes uniform steps. How does variable step-size affect predictive accuracy and planner stability, and can continuous-time models help?

- Code/data release scope: Reproducibility details (e.g., calibration procedures, cost tuning, MPC settings) are limited. What documentation and artifacts are needed for reliable replication and extension by the community?

Glossary

- AdaLN: Adaptive Layer Normalization used to condition transformer layers on auxiliary signals. "CDiT provides strong action conditioning via AdaLN~\cite{peebles2023scalable} layers"

- Allegro gripper: A multi-fingered robotic hand designed for dexterous manipulation. "Franka Panda arm equipped with an Allegro gripper"

- Autoregressive: A prediction style where future states are generated by feeding previous model outputs back into the model. "we perform multistep prediction by autoregressively feeding the predicted state"

- CDiT (Conditional Diffusion Transformers): A transformer architecture that conditions generation/prediction on actions or other inputs. "Our predictor architecture is based on Conditional Diffusion Transformers (CDiT)~\cite{bar2025navigation}"

- Cross-Embodiment Dynamics: Dynamics modeling that transfers across different agent bodies (e.g., human to robot). "world models~\cite{he2025scaling, honglearning} have been used to learn cross-embodiment dynamics by representing embodiments as sets of 3D particles"

- Cross-Entropy Method (CEM): A stochastic optimization algorithm that iteratively refines a distribution to minimize a cost. "We use the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM)~\cite{crossentropymethod} to optimize the joint angles"

- Dexterous manipulation: Fine-grained control of multi-fingered hands to interact with objects through complex contacts. "Dexterous manipulation is challenging because it requires understanding how subtle hand motion influences the environment through contact with objects"

- Diffusion Forcing: A technique that combines next-token prediction with diffusion to stabilize autoregressive generation. "Diffusion Forcing~\citep{chen2024diffusion} addresses this issue"

- Diffusion Policy: A generative action policy that uses diffusion models to output multi-step actions from observations and goals. "outperforming Diffusion Policy by over 50\% on average"

- DINOv2: A self-supervised vision transformer encoder producing semantically rich image embeddings. "Images are encoded into latent states using a frozen DINOv2~\cite{DINOv2} encoder"

- Egocentric: First-person viewpoint capturing from the agent’s perspective. "we pre-train DexWM on EgoDex~\cite{egodex}, a large-scale egocentric human interaction dataset"

- Embodiment gap: The mismatch between the morphology or sensors/actuators of different agents (e.g., humans vs. robots). "to reduce the embodiment gap"

- End-effector: The terminal device of a robot (e.g., gripper) that interacts with the environment. "For the grasping task, we also add a cost on end-effector orientation"

- Euler angles: A 3-parameter representation of 3D orientation via rotations about coordinate axes. "orientation (as Euler angles)"

- Forward kinematics: Computing end-effector or keypoint positions from known joint angles and link parameters. "we compute the keypoints using the forward kinematics from known joint angles of the robot and grippers"

- Franka Panda arm: A 7-DOF robotic manipulator commonly used in research. "When deployed on a real-world Franka Panda robot with Allegro grippers"

- Hand Consistency Loss: An auxiliary objective encouraging predicted states to preserve accurate hand configurations. "we introduce an auxiliary hand consistency loss that enforces accurate hand configurations"

- Heatmaps: Spatial probability maps indicating likely locations of keypoints in an image. "predict heatmaps of the fingertip and wrist locations"

- In-hand manipulation: Manipulating objects using finger motions while maintaining grasp, often without placing the object down. "executing in-hand manipulation"

- Latent space: The feature space produced by an encoder where high-level semantics are represented. "simulate complex manipulation trajectories in the latent space"

- Latent state: A compact representation of the environment’s state derived from observations. "predicts the next latent state of the environment"

- MANO: A parametric hand model defining 3D hand shape and pose via keypoints and deformation parameters. "Following the MANO~\cite{mano} parameterization"

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A planning framework that optimizes a sequence of actions using a predictive model at test time. "within an MPC framework"

- Open-loop trajectory simulation: Predicting future states without feedback or corrective updates from the environment during rollout. "in open-loop trajectory simulation"

- Patch-level features: Encoder outputs per image patch used as tokens or state representations. "we utilize patch-level features as the latent state"

- PCK@20: Percentage of Correct Keypoints within a 20-pixel radius, a metric for keypoint localization accuracy. "Percentage of Correct Keypoints@20 (PCK@20)"

- Rigid transformation: A rotation and translation mapping points between coordinate frames without deformation. "we use the known rigid transformation "

- SigLIP 2: A language-supervised image encoder producing embeddings aligned with text semantics. "language-supervised image models (SigLIP 2~\cite{siglip2})"

- Sim2real: Techniques to transfer skills learned in simulation to real-world robots. "Sim2real techniques, in particular, have enabled robots to perform complex tasks"

- State transition model: A predictive function that maps current state and action to the next state. "DexWM is used as a state transition model in an MPC optimization framework"

- V-JEPA 2: A self-supervised video encoder learning predictive representations from spatiotemporal masking objectives. "video (V-JEPA 2~\cite{vjepa2}) models"

- Waypoint trajectories: Sequences of intermediate target poses for guiding motion planning and control. "planning waypoint trajectories"

- Zero-shot generalization: Performing unseen tasks without task-specific training or fine-tuning. "demonstrates strong zero-shot generalization to unseen manipulation skills"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be piloted or deployed with current tools and modest integration effort, leveraging the paper’s demonstrated zero-shot grasping on a real robot and planning from image goals.

- Goal-conditioned pick, place, and reach planning for existing robot arms with dexterous grippers (Sectors: robotics, logistics, manufacturing)

- What: Use DexWM as a state-transition model in a model predictive control (MPC) loop to plan waypoint trajectories for basic manipulation tasks (reach, grasp, place) with image goals.

- Why: Demonstrated 83% zero-shot grasp success on Franka Panda + Allegro without real-world fine-tuning; >50% average improvement over Diffusion Policy on simulated tasks.

- Tools/Workflow:

DexWM + DINOv2latent features, CEM optimizer, goal images, forward kinematics; integrate with ROS2/MoveIt as a planning plugin; low-level impedance/position controllers handle execution. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to a dexterous end-effector (e.g., Allegro), accurate camera calibration and extrinsics, forward kinematics, real-time compute for CEM; requires subgoals for longer-horizon tasks; limited tactile feedback.

- Data-efficient skill bootstrapping from human video for new robot platforms (Sectors: robotics, software)

- What: Pretrain on large-scale human egocentric video (EgoDex) and small amounts of platform-specific exploratory sim data to reduce/avoid expensive teleoperation datasets.

- Why: The paper shows ~4 hours of non-task-specific sim data suffices to bridge embodiment gaps and enable zero-shot transfer.

- Tools/Workflow: Egocentric datasets with hand keypoints; RoboCasa/RoboSuite for exploratory data;

MANO-style hand keypoints; fine-tuning DexWM on platform-specific exploratory rollouts. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Hand keypoint annotations and camera pose or reliable forward kinematics; dataset licensing and privacy compliance for human videos.

- Counterfactual action testing and policy debugging in simulation (Sectors: robotics QA, software testing)

- What: Use DexWM to roll out “atomic” action perturbations (up, down, left, right, open/close) to probe object-hand interaction dynamics without running real hardware.

- Why: The model tracks keypoints and scene responses (e.g., cup movement on collision), enabling targeted safety and robustness checks.

- Tools/Workflow: Autoregressive multistep prediction in DINOv2 latent space; visualize predicted heatmaps for hand consistency.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Deterministic dynamics assumption; quality of encoder features; fidelity of sim scenes to real-world setups.

- Action retargeting from reference trajectories to new scenes (Sectors: robotics integration, content-to-robot pipelines)

- What: Copy action sequences (3D hand keypoint deltas + camera motion) from human or reference videos to drive new rollouts in different environments.

- Why: DexWM retained fine-grained hand state fidelity better than baselines; useful for fast skill prototyping from existing footage.

- Tools/Workflow: Extract MANO keypoints from reference; transform actions to target frame; plan and execute via robot kinematics.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Pose tracking accuracy; geometric differences between scenes may require minor goal shaping/subgoals.

- Planning with image goals for non-annotated exploratory data (Sectors: robotics R&D, warehouse labs)

- What: Train/fine-tune on unlabeled exploratory trajectories and use goal images at inference time to accomplish tasks.

- Why: Diffusion Policy struggled on exploratory-only data; DexWM succeeded via planning over learned dynamics rather than direct action prediction.

- Tools/Workflow: Goal image selection;

L2latent distance + keypoint-based planning cost; CEM. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Goals must be visually reachable in latent space; camera viewpoints should be consistent.

- Rapid embodiment transfer for new dexterous hands and cameras (Sectors: robotics OEMs)

- What: Swap the backbone encoder or adapt action representation with a small projection layer; re-use the same planning stack.

- Why: Ablations show modularity to different encoders (DINOv2, SigLIP2, V-JEPA 2) with minor tuning.

- Tools/Workflow: Lightweight adapter layers for embedding dimension; embedding normalization; calibration scripts for new rigs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Comparable feature quality; retraining/adaptation may be required for some tasks.

- Vision-only skill libraries powered by human video (Sectors: education, makers/hobbyists)

- What: Use egocentric internet videos with hand keypoints to create basic manipulation behaviors on low-cost arms/grippers in simulation or controlled settings.

- Why: Minimizes need for expert teleoperation; encourages community experimentation and curriculum creation.

- Tools/Workflow: Public datasets (EgoDex, Ego4D) with hand annotations; small exploratory sim runs; open-source DexWM pipeline.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Legal use and consent for training on human videos; quality of consumer hardware may limit performance.

- Safety rehearsal and what-if analysis before floor deployment (Sectors: manufacturing, logistics)

- What: Use DexWM to simulate contact-rich sequences under different action sequences to assess drop risks, collisions, or hand-object interference.

- Why: Model captures hand-object motion coupling; can reveal hazards from gripper openings/closures at wrong timings.

- Tools/Workflow: Scenario libraries (e.g., kitting, small-part grasp); MPC with constraint checks; internal QA dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Deterministic rollouts approximate risk; does not replace force/torque safety measures.

- Research benchmarks for dexterous world models (Sectors: academia)

- What: Adopt PCK@20 for hand accuracy, latent L2 for perceptual similarity, and zero-shot transfer success as standard metrics.

- Why: Paper shows PCK captures dexterity better than general perceptual metrics; encourages comparable reporting.

- Tools/Workflow: Shared evaluation code; RoboCasa tasks; open baselines (NWM*, PEVA*).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of hand heatmaps and calibration; community adoption.

- Privacy- and license-aware data pipelines for human video training (Sectors: policy/compliance, dataset providers)

- What: Implement datasets and processes with explicit consent, license tracking, and anonymization where needed.

- Why: The approach leverages large-scale human video; compliance is essential for industrial adoption.

- Tools/Workflow: Dataset governance (consent logs, purpose limitation), PII-safe annotation of hands, contracts for redistribution.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Clear rights frameworks and internal review; regional data protection laws (e.g., GDPR/CCPA).

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities are plausible extensions that need further research, scaling, or additional sensing/tooling (e.g., tactile, force feedback, hierarchical planners).

- Generalist household assistants with fine manipulation (Sectors: consumer robotics, eldercare)

- What: Cooking prep, tidying, laundry folding, opening containers, tool use.

- Needed advances: Hierarchical planning for long horizons, robust subgoal discovery, improved tactile integration and safety guards.

- Dependencies: Affordable dexterous hands; robust perception in clutter; home-grade safety certification.

- Surgical and micro-assembly assistance (Sectors: healthcare, advanced manufacturing)

- What: Delicate grasping, threading, suturing assistance, component insertion.

- Needed advances: Sub-millimeter accuracy, integration with force/tactile sensors, domain adaptation to medical imagery, rigorous validation and regulation.

- Dependencies: FDA/CE approvals; sterile design; traceable logs; clinician-in-the-loop workflows.

- Skill libraries distilled from internet-scale egocentric video to robots (Sectors: robotics platforms, content-to-robot services)

- What: “Egocentric-to-Robot” toolkits that automatically mine, segment, and convert human hand-object behaviors into robot-executable skills.

- Needed advances: Reliable action parsing, automatic retargeting across embodiments, goal inference from text or language narration.

- Dependencies: Large scalable annotation pipelines; copyright/consent compliance; robust sim-to-real validation.

- Text- and language-goal planning in dexterous world models (Sectors: software, enterprise automation)

- What: Extend goals beyond images to natural language (e.g., “pick the blue cap and place it in the right bin”).

- Needed advances: Multimodal grounding between language and latent dynamics; constraints handling; disambiguation in clutter.

- Dependencies: VLM/VLA integration; dataset curation with paired instructions and egocentric demonstrations.

- Shared autonomy and teleoperation assistance (Sectors: remote operations, hazardous environments)

- What: World model proposes safe waypoint plans while human operators provide high-level guidance; handle hazardous materials or disaster response.

- Needed advances: Low-latency planning, uncertainty quantification, fail-safe control blending.

- Dependencies: Reliable comms; certified safety overrides; operator training.

- Closed-loop learning: planning + on-policy data collection (Sectors: robotics R&D)

- What: Use DexWM in the loop to propose plans, execute, and self-improve dynamics via new data, reducing human labeling.

- Needed advances: Online learning with safety constraints, drift detection, continual representation learning without catastrophic forgetting.

- Dependencies: Real-time compute budgets; sandboxes for safe exploration.

- Multi-arm and mobile manipulator coordination (Sectors: warehousing, hospital logistics)

- What: Coordinated handoffs, bimanual manipulation, mobile pick-and-place in dynamic scenes.

- Needed advances: Multi-agent/multi-embodiment dynamics modeling; global-local planning hierarchies; SLAM integration.

- Dependencies: Accurate multi-camera calibration; fleet-level scheduling; safety zones.

- Tactile-visual world models for robust grasping and in-hand manipulation (Sectors: robotics, precision engineering)

- What: Integrate touch to improve stability in placing/transport and enable dexterous in-hand reorientation.

- Needed advances: Multisensory latent spaces; contact-rich dynamics; fast planners beyond CEM (e.g., gradient-based MPC).

- Dependencies: High-quality tactile sensors; calibration between vision and touch; controller co-design.

- Standardization and regulation for video-trained embodied AI (Sectors: policy/regulation)

- What: Standards for dataset transparency, sim-to-real validation protocols, liability frameworks for world-model-driven planning.

- Needed advances: Third-party testing regimes, audit trails for training data and model updates, incident reporting templates.

- Dependencies: Cross-industry bodies (e.g., ISO/IEC, IEEE) and sector-specific regulators; alignment with privacy laws.

- Sustainable training and deployment practices (Sectors: policy, enterprise ESG)

- What: Energy-efficient model scaling and inference; shared pretraining hubs for world-model backbones.

- Needed advances: Efficient architectures (e.g., distilled or sparse predictors), low-cost adaptation methods, green compute strategies.

- Dependencies: Shared infrastructure; reporting of energy usage; incentives for reuse versus retraining.

Notes on feasibility and cross-cutting assumptions

- Deterministic dynamics assumption in DexWM simplifies inference but may limit performance in stochastic or deformable-object scenarios; uncertainty-aware extensions are advisable for safety-critical domains.

- Accurate hand keypoints and camera pose are core dependencies; for practical deployment, robust, low-latency pose estimation and calibration are essential.

- Planning currently uses CEM and may be slow for long horizons; adopting more sample-efficient or gradient-based MPC will improve responsiveness.

- World models presently benefit from subgoals and hierarchical structures for complex tasks; productization for long workflows (e.g., cooking) needs hierarchical planning and task decomposition.

- Compliance, licensing, and privacy for human video training must be addressed from the outset to enable commercial use.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.

*Figure 7: Direct hand motion conditioning offers superior trajectory tracking over text-conditioned models.

*Figure 7: Direct hand motion conditioning offers superior trajectory tracking over text-conditioned models.