EMMA: Efficient Multimodal Understanding, Generation, and Editing with a Unified Architecture

Abstract: We propose EMMA, an efficient and unified architecture for multimodal understanding, generation and editing. Specifically, EMMA primarily consists of 1) An efficient autoencoder with a 32x compression ratio, which significantly reduces the number of tokens required for generation. This also ensures the training balance between understanding and generation tasks by applying the same compression ratio to images. 2) Channel-wise concatenation instead of token-wise concatenation among visual understanding and generation tokens, which further reduces the visual tokens in unified architectures. 3) A shared-and-decoupled network that enables mutual improvements across tasks while meeting the task-specific modeling requirements. 4) A mixture-of-experts mechanism adopted for visual understanding encoder, which substantially improves perceptual capabilities with a few parameters increase. Extensive experiments have shown that EMMA-4B can significantly outperform state-of-the-art unified multimodal approaches (e.g., BAGEL-7B) in both efficiency and performance, while also achieving competitive results compared to recent multimodal understanding and generation experts (e.g., Qwen3-VL and Qwen-Image). We believe that EMMA lays a solid foundation for the future development of unified multimodal architectures.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces EMMA, a single AI system that can understand images, create images from text, and edit images—all inside one unified model. Think of it as a smart “all-in-one” tool that reads, draws, and edits pictures efficiently and well.

Objectives

The researchers wanted to solve a big problem: it’s hard to train one model to do both understanding (like answering questions about a picture) and generation (like making or editing a picture) without wasting time and computer power. Their goals were to:

- Build one model that handles understanding, generation, and editing together.

- Make it fast and efficient by reducing how much information the model needs to process.

- Keep or improve quality compared to larger, specialized models.

Methods and Approach

To reach these goals, EMMA uses a few clever design ideas. Here’s what they did, explained with simple analogies:

Key ideas in simple terms

- High compression for images: They use an “autoencoder,” which is like a shrink-and-expand machine for pictures. It squashes a big image into a small, compact form (32× smaller) and later rebuilds it. This makes the model much faster because it handles fewer “pieces” of information.

- Fewer “pieces” to process (tokens): Tokens are like tiny puzzle pieces of information the model reads. EMMA reduces the number of visual tokens needed, so it can work quicker without losing important details.

- Smart stacking of information (channel-wise concatenation): Imagine stacking two layers of a sandwich instead of making two full sandwiches. EMMA stacks the understanding info (what’s in the picture) with the generation info (how to draw details) without increasing the number of tokens. This keeps things efficient and fused together.

- Shared-and-decoupled network: Early layers in the model are shared—like basic classes all students take. Later layers split into specialized paths—like choosing a major—so the understanding part and the generation part can learn what they each need best.

- Mixture of Experts (MoE) for tricky images: The model includes specialists for certain image types (like math and science diagrams). A “router” picks the right expert when needed, like a guidance counselor directing you to the right tutor.

How it learns:

- For understanding (I2T), it learns by predicting the next word, similar to how chatbots learn to continue a sentence.

- For generating images (T2I and editing), it uses a “flow” method, which is like planning a smooth path to turn text into a final picture step by step.

Training data and steps:

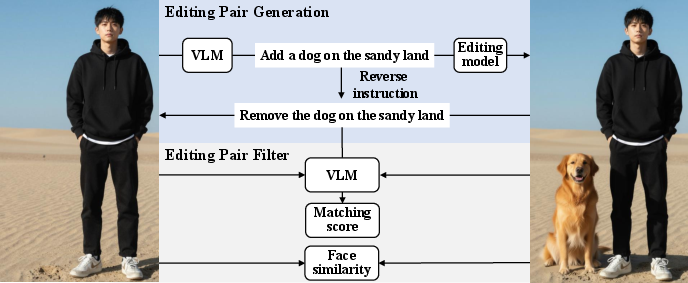

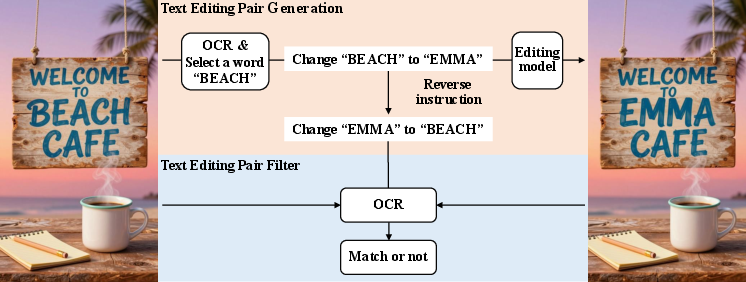

- EMMA trains on huge sets of multimodal data (images with text), high-quality image generation data, and image editing examples.

- It trains in stages: align visual features, pre-train, fine-tune, polish quality, then add and train the special STEM expert and the router.

Main Findings and Why They’re Important

The paper reports strong results:

- Better performance with a smaller model: EMMA uses a 4-billion-parameter LLM but beats larger unified models. For example, it scores 73.0 on MMVet (a tough vision test) versus 67.2 for BAGEL-7B.

- Strong image generation: On GenEval (a test of how well images match the text), EMMA scores 0.91 without tricks like prompt rewriting, and 0.93 with it—better than many unified models and competitive with specialized image generators.

- Efficient image editing: On GEdit, EMMA slightly edges out similar unified models while using only about 20% of the visual tokens they need (around 5× fewer tokens for editing tasks), making it faster and cheaper to run.

Why this matters:

- EMMA shows you can have one unified model that does multiple hard tasks well, without being huge or slow.

- It proves smart design (compression, stacking, shared-then-specialized layers, experts) can beat brute force size.

Implications and Potential Impact

- Faster, cheaper AI systems: Because EMMA needs fewer tokens and smarter compression, it can run more efficiently—great for real-world apps, especially on limited hardware.

- One model for many jobs: EMMA’s unified design hints at future AI that can read, reason, draw, and edit—moving toward more general-purpose AI.

- Better cross-modal tools: EMMA can handle complex instructions and even support other languages (like Chinese) in generation and editing, showing useful “emergent” abilities.

- Raises the bar for evaluation: The authors point out current editing tests don’t fully measure “subject consistency” (keeping the same person/object intact), which suggests we need better benchmarks to fairly judge image editing quality.

In short, EMMA is a practical step toward powerful, unified multimodal AI that’s both efficient and capable—helping bridge the gap between understanding and creating visual content in one model.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, written to be actionable for follow‑up research.

- Quantify the trade‑offs of the 32× compression in both understanding and generation:

- Systematically ablate compression ratios (e.g., 8×/16×/32×) at fixed compute and measure effects on high‑frequency detail, small objects, text rendering accuracy, and spatial localization.

- Evaluate identity/subject preservation in generation and editing under different compression settings using face similarity (e.g., ArcFace/CosFace), LPIPS, FID/KID, and pick‑score/human studies.

- Validate spatial alignment assumptions behind channel‑wise concatenation:

- Confirm that Und‑Enc (SigLIP2 + 2×2 pixel shuffle) and Gen‑Enc (DCAE) latents align to the same spatial grid across native resolutions and aspect ratios.

- Investigate learned alignment modules (e.g., deformable alignment, cross‑attention alignment) versus raw channel concatenation, and compare against token‑wise fusion, cross‑modal attention, and gated fusion.

- Provide ablations for the shared‑and‑decoupled architecture:

- Explore how the depth/extent of shared layers affects task performance, stability, and negative transfer.

- Examine gradient interference between next‑token prediction (Und) and flow‑matching (Gen) in shared layers; test gradient surgery, loss weighting, alternating schedules, or adapters to mitigate conflicts.

- Clarify and assess the MoE routing and expert design:

- Specify router features, training signals, and misrouting rates; study calibration and uncertainty.

- Evaluate more domains beyond STEM (e.g., medical, documents, charts, OCR, UI) and consider token‑/region‑level routing versus image‑level routing.

- Analyze expert load balancing, memory/latency overhead, and dynamic expert expansion policies.

- Positional encoding choices remain underexplored:

- Ablate the combination of 2D positional encoding for visual tokens with 1D RoPE in the LLM, and compare alternatives (pure 2D RoPE, rotary hybrids, learned 2D embeddings).

- Measure impacts on spatial reasoning (e.g., MMVet spatial subsets, synthetic layout tasks) and on variable‑resolution/aspect‑ratio inputs.

- Attention masking strategy merits deeper analysis:

- Study the impact of hybrid attention (visual tokens attending each other within an image for Gen) on multi‑image contexts, multi‑turn editing, and long visual sequences.

- Evaluate alternative masking patterns (e.g., block causal, bidirectional windows) on both alignment (GenEval) and image quality (DPG‑Bench, aesthetic metrics).

- Editing evaluation and metrics are insufficiently addressed:

- Propose and validate metrics for subject/identity consistency, localized accuracy (mask fidelity), and instruction adherence beyond VLM judgments (e.g., segmentation overlap, localized CLIP‑based checks, OCR for text edits).

- Create a benchmark with controlled identity preservation scenarios and region‑based edits to avoid metric gaming and to reflect real‑world editing constraints.

- Data transparency and potential leakage:

- Document internal datasets, deduplication procedures, and steps taken to prevent test set contamination (e.g., MMVet/GenEval/GEdit).

- Analyze dataset composition biases (e.g., portrait vs. non‑portrait, languages, domains) and their effect on performance and fairness.

- Efficiency claims lack end‑to‑end measurements:

- Report wall‑clock training/inference latency, memory footprint, token throughput, and energy usage versus baselines (e.g., BAGEL‑7B, Qwen‑Image) under matched settings.

- Quantify how much of the observed gains come specifically from token reduction versus architectural or data differences.

- High‑resolution generation/editing scalability is unclear:

- Evaluate performance and stability at 2K–8K resolutions (T2I and IT2I), including tiling/consistency across tiles, detail recovery, and runtime memory behavior.

- Role of the frozen DCAE in overall capability:

- Examine end‑to‑end fine‑tuning of DCAE versus keeping it frozen; quantify impacts on fidelity, robustness, and editing precision.

- Compare different AEs/VAEs trained for 32× with reconstruction/regularization trade‑offs.

- Cross‑lingual capabilities are anecdotal:

- Conduct systematic multilingual evaluations (Chinese and additional languages) for understanding, T2I, and IT2I, including text rendering quality, instruction adherence, and editing correctness.

- Safety, misuse, and provenance are not discussed:

- Assess content safety (NSFW, harmful edits), demographic bias in generation/editing, watermarking/provenance, and mechanisms to prevent identity manipulation misuse.

- Scaling laws and model size effects remain unexplored:

- Characterize how performance scales with LLM size and visual encoder capacity; identify diminishing returns and optimal parameter allocations between Und/Gen branches and experts.

- Negative transfer and synergy claims need quantification:

- Provide controlled experiments showing when joint training improves one task via the other (and when it hurts), including ablations that remove Und‑Enc or Gen‑Enc, or train tasks separately before merging.

- Robustness to challenging inputs is untested:

- Evaluate performance under noise, blur, compression, occlusion, low‑light, small objects, adversarial perturbations, and domain shifts (e.g., medical, satellite).

- Multi‑image/multi‑modal extensions are not addressed:

- Investigate unified handling of video, audio, depth/3D, and multi‑image composition tasks (e.g., image‑pair reasoning, collage generation) within the same architecture and attention scheme.

- Training curricula and sampling strategies need study:

- Ablate the 1:1:1 mixture in SFT/QT, portrait/general balance, and STEM/general balance; explore curriculum learning and adaptive sampling based on performance gradients.

- Reproducibility and open‑sourcing gaps:

- Provide code, training recipes, checkpoints, and detailed hyperparameters (e.g., flow matching schedules, bucket sizes, augmentations) to enable third‑party replication and fair comparisons.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable, sector-linked use cases that can be deployed now, given EMMA’s reported performance, efficiency (32× compression, channel-wise fusion), and unified understanding–generation–editing capabilities.

- Software/Creative tools (software, media/advertising)

- Natural-language image editor and generator: integrate EMMA’s IT2I and T2I into design suites (e.g., plugins for Photoshop, Figma) to perform object addition/removal/replacement, background/tone transfer, text rendering, and multi-step edits from instructions.

- Brand-safe creative co-pilot: generate on-brief concepts and edit assets while preserving subject consistency (leveraging EMMA’s better alignment scores without RL/prompt rewriting).

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU/accelerator availability, integration via an SDK/API, human review for brand safety, subject-consistency checks; licensing and access to EMMA weights and DCAE/SigLIP2 components.

- E-commerce and retail (commerce, marketing)

- Product image workflows: automatic background transfer, color correction, layout/position adherence, and text overlays that match prompt specifications; support “virtual try-on” style edits from catalog instructions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: high-resolution inputs (supported buckets at ~1K), fairness/accuracy safeguards to avoid misrepresentation, batch processing pipelines, face-similarity filters for portraits (as in the paper’s editing data pipeline).

- Document AI and analytics (finance, enterprise software)

- Robust document and chart understanding: deploy EMMA for DocVQA, ChartQA, OCR-driven extraction, and visual reasoning on forms/tables to convert scanned documents into structured data and answers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-specific fine-tuning for document types, privacy/compliance controls (PII handling), reliable OCR integration and native-resolution support.

- Education and training (education, edtech)

- Visual tutoring and content generation: use EMMA’s math/diagram reasoning (MathVista/MMMU competitiveness) to explain problems with image context, generate illustrative images, and follow multi-step instructions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: curriculum alignment, content moderation, multi-language support where needed (EMMA shows emergent Chinese instruction handling via its understanding branch).

- Accessibility and assistive tech (public sector, consumer apps)

- Image-to-text descriptions and alt-text generation: on-device or low-latency services that describe scenes, diagrams, and documents for visually impaired users; support Chinese and English instructions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: model quantization for edge devices, latency targets, user privacy safeguards.

- Customer support and field service (enterprise, IoT/edge)

- Visual ticket triage and guided fixes: interpret user-submitted images, annotate issues, and generate edited examples showing corrective steps (e.g., highlight components, overlay instructions).

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain fine-tuning (equipment, components), secure handling of customer data, workflow integration with ticketing systems.

- Content moderation and compliance (policy, platform safety)

- Prompt–image alignment checks: use EMMA’s alignment strengths to pre-screen generated assets for adherence to specified attributes (colors, positions, counts) before publishing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: threshold calibration, audit logs, bias testing; a governance layer to flag risky edits (e.g., identity manipulation).

- Synthetic data creation pipelines (software, ML ops)

- High-quality dataset generation: reproduce the paper’s editing data factory (VLM-instruction + editing + filtering + reversed pairs) to synthesize training data for text rendering, editing, and domain-specific tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: filtering via VLM and face-similarity/OCR modules, license checks on source images, careful exclusion of datasets that harm subject consistency (e.g., GPT-Image-Edit-1.5M).

- Edge/mobile deployment for multimodal tasks (devices, telecom)

- Low-token inference for on-device understanding/editing: leverage 32× compression and channel-wise fusion to enable lightweight image captioning, simple edits, and localized generation on mobile/AR devices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: quantization, hardware acceleration (NPUs), energy constraints, caching for positional encodings; acceptable quality at reduced context size.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases will likely require further research, scaling, domain adaptation, or ecosystem development (e.g., expanded MoE experts, improved metrics, video/3D extension).

- Robotics and embodied AI (robotics)

- Unified perception–instruction following: extend EMMA to 3D/video inputs for scene understanding and task execution; use generation/editing to plan or simulate changes (simulation-to-reality).

- Assumptions/dependencies: temporal modeling, 3D perception, safety verification, low-latency control loops; additional experts (MoE) for robotics visuals.

- AR/VR and spatial computing (software, consumer hardware)

- Real-time generative overlays and environment edits: live augmentation of scenes (e.g., instructional overlays, visual corrections) guided by natural-language prompts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stringent latency budgets, streaming token pipelines, robust spatial priors beyond 2D positional encodings, device-side acceleration.

- Healthcare imaging and reporting (healthcare)

- Medical visual understanding and report assistance: domain-specific MoE experts to interpret radiology/pathology images and align with clinical narratives; careful use of editing for anonymization/annotation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: medical-grade datasets, regulatory compliance (HIPAA/GDPR), rigorous validation; avoid generative edits that could mislead diagnostics.

- Industrial inspection and energy (manufacturing, energy)

- Automated reading of gauges/diagrams and guided maintenance: convert visual telemetry/diagrams into actionable instructions; generate annotated edits showing steps or risks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain data, ruggedized edge deployment, safety certification, integration with SCADA/CMMS systems.

- Finance and business intelligence (finance, enterprise analytics)

- Chart reasoning and narrative generation at scale: explain financial charts, detect inconsistencies, and auto-generate dashboards with visuals created/edited per specifications.

- Assumptions/dependencies: auditability, accuracy guarantees, provenance tracking of generated assets, compliance with disclosure standards.

- Standards and policy for image editing (policy, governance)

- Subject-consistency metrics and certification: develop benchmarks that evaluate identity/subject preservation; mandate watermarking and provenance for edited media.

- Assumptions/dependencies: community adoption, regulator involvement, platform enforcement mechanisms; tooling to measure and report consistency.

- Multimodal IDEs and agent platforms (software, developer tools)

- Unified agent that handles understanding, generation, and editing in a single toolchain (reducing orchestration complexity across separate models).

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust APIs, plugin ecosystems, strong guardrails, configurable attention strategies for mixed tasks.

- Video generation and editing (media/entertainment)

- Extend EMMA’s architecture to temporal data using similar compression and fusion strategies for high-frame-rate video editing/generation and instruction-based transformations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: temporal coherence models, compute scaling, new loss functions (flow/diffusion) tuned for video; benchmarking beyond still images.

- Multilingual expansion with task-aware experts (global markets, education)

- Router-driven MoE for language-specific visual tasks (e.g., diagrams/text in diverse scripts), enabling native T2I/IT2I beyond English/Chinese.

- Assumptions/dependencies: diverse multilingual datasets, language-aware routing, OCR/text rendering across scripts, safety for culturally sensitive content.

- Privacy-preserving/federated deployments (public sector, enterprise)

- On-premise EMMA variants with MoE tuned to local domains; federated learning for updates without moving sensitive images off-site.

- Assumptions/dependencies: federated training infrastructure, secure adapters, differential privacy, compliance audits.

These applications build directly on EMMA’s innovations—32× compression via autoencoder, channel-wise token fusion, shared-and-decoupled architecture, and MoE vision experts—translating architectural efficiency and performance gains into concrete tools, workflows, and sectoral value. Each long-term item depends on further research or ecosystem maturation (e.g., domain data, metrics, safety), while immediate items can be productized with existing integration and governance practices.

Glossary

- 1D RoPE: A rotary positional embedding applied along a single dimension to encode token order within transformer models. "processed using the positional embedding of 1D RoPE~\cite{rope}."

- 2D positional encoding: A spatial positional encoding that injects 2D location information into visual tokens. "before feeding visual tokens into the LLM, the 2D positional encoding is applied to incorporate spatial priors."

- 2x2 token merging strategy: A heuristic that merges nearby visual tokens in a 2x2 grid to reduce sequence length for generation models. "and 2x2 token merging strategy, EMMA only requires 1/4 visual tokens for the generation task."

- Adapter: A lightweight projection module used to interface modality-specific encoders with a unified backbone. "only the adapter in Und branch is tuned."

- Autoencoder (AE): A neural architecture that compresses and reconstructs images, often used to tokenize high-resolution visuals for generation. "the autoencoder (AE) with an 8x compression ratio (e.g., the AE in FLUX~\cite{flux2024})"

- Casual masking: A masking scheme (commonly “causal”) where tokens only attend to previous positions to preserve autoregressive order. "Specifically, pure casual masking is utilized to both textual and visual tokens in Und tasks."

- Channel dimension: The feature axis along which per-token vectors are concatenated to fuse information without increasing token count. "concatenated along the channel dimension instead of the token level like BAGEL~\cite{deng2025BAGEL}."

- Channel-wise concatenation: Concatenating features along channels (not across tokens) to fuse understanding and generation features efficiently. "Channel-wise concatenation instead of token-wise concatenation among visual understanding and generation tokens, which further reduces the visual tokens in unified architectures."

- Compression ratio: The factor by which an encoder reduces image size or token count, balancing efficiency and fidelity. "An efficient autoencoder with a 32x compression ratio, which significantly reduces the number of tokens required for generation."

- Cross-task parameter sharing: Sharing subsets of parameters across tasks to encourage mutual improvement while preserving task-specific behavior. "introduces cross-task parameter sharing at shallow layers to facilitate mutual improvements between multimodal tasks,"

- DCAE: A deep compression autoencoder optimized for high-resolution diffusion models to produce compact yet informative visual latents. "EMMA first uses a higher-compression autoencoder (DCAE~\cite{chen2024deep}, 32x compression), that aligns the compression ratio in the visual understanding branch."

- Flow matching: A training objective for generative models that learns a velocity field to transform noise into data distributions. "For Gen tasks, EMMA utilizes flow matching with velocity prediction."

- Gen-Enc (generation encoder): The visual encoder branch specialized for image generation, producing tokens optimized for synthesis. "For Gen-Enc, we employ a high-compression autoencoder, DCAE~\cite{dcae}, with a 32Ã compression ratio."

- High-frequency details: Fine-grained visual information (textures/edges) critical for photorealistic image synthesis. "generation (semantics and high-frequency details modeling~\cite{ma2025deco}) tasks."

- Hybrid attention strategy: An attention configuration that mixes different masking rules across modalities or token types. "Following Transfusion~\cite{zhou2024transfusion}, EMMA adopts a hybrid attention strategy."

- LLM: A transformer-based LLM that processes visual tokens and text jointly for multimodal tasks. "followed by a 2x2 pixel shuffle strategy~\cite{internvl15} to further reduce these tokens to one quarter before feeding them into the LLM."

- Mix-of-experts (MoE): A modular architecture where a router selects among specialized experts to process inputs more effectively. "EMMA also integrates a mix-of-experts (MoE) strategy into the visual understanding encoder"

- Next-token prediction: An autoregressive learning paradigm where models predict the subsequent token in a sequence. "As for Und tasks, EMMA utilizes the next-token prediction mechanism to guide overall learning."

- Parameter decoupling: Keeping subsets of parameters independent across tasks to satisfy distinct modeling requirements. "employing parameter decoupling at deeper layers to meet the distinct modeling requirements of understanding and generation."

- Patchfy operation: The (patchify) process that splits images into fixed-size patches to form input tokens for vision transformers. "Und-Enc, through the patchfy operation in SigLIP2 and pixel shuffling strategy, achieves a 32Ã compression ratio of the input image."

- Pixel shuffle: A transformation that reorganizes spatial information to reduce token count while preserving structure (e.g., 2x2). "followed by a 2x2 pixel shuffle strategy~\cite{internvl15} to further reduce these tokens to one quarter"

- Positional embeddings: Learned vectors added to tokens to encode their positions in sequences or grids. "we extend its capability to support native resolutions of input images by interpolating the positional embeddings."

- Router module: A gating component that routes inputs to the most suitable expert in a mixture-of-experts system. "with a router module dynamically selecting the appropriate expert for each input."

- Self-attention layers: Transformer layers that compute token-to-token dependencies for cross-modal interaction. "Moreover, cross-modal interactions are achieved through self-attention layers."

- SigLIP2: A modern vision-language encoder variant of SigLIP with improved semantic understanding and localization capabilities. "we directly utilize SigLIP2-so400m-patch16-512~\cite{siglip2} as Und-Enc."

- STEM expert: A specialized MoE expert tailored to scientific/technical visual data (charts, equations, diagrams). "EMMA additionally introduces a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) expert to process STEM images,"

- Token-wise concatenation: Concatenating along the token axis, increasing sequence length and computational cost. "Channel-wise concatenation instead of token-wise concatenation among visual understanding and generation tokens,"

- Und-Enc (understanding encoder): The visual encoder branch focused on extracting semantic features for multimodal understanding. "For Und-Enc, recent works generally adopt SigLIP~\cite{siglip,siglip2} to encode images as visual tokens"

- Visual tokens: Discrete vectors representing image patches/features for integration with LLMs. "recent works generally adopt SigLIP~\cite{siglip,siglip2} to encode images as visual tokens"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.