Measuring Agents in Production (2512.04123v1)

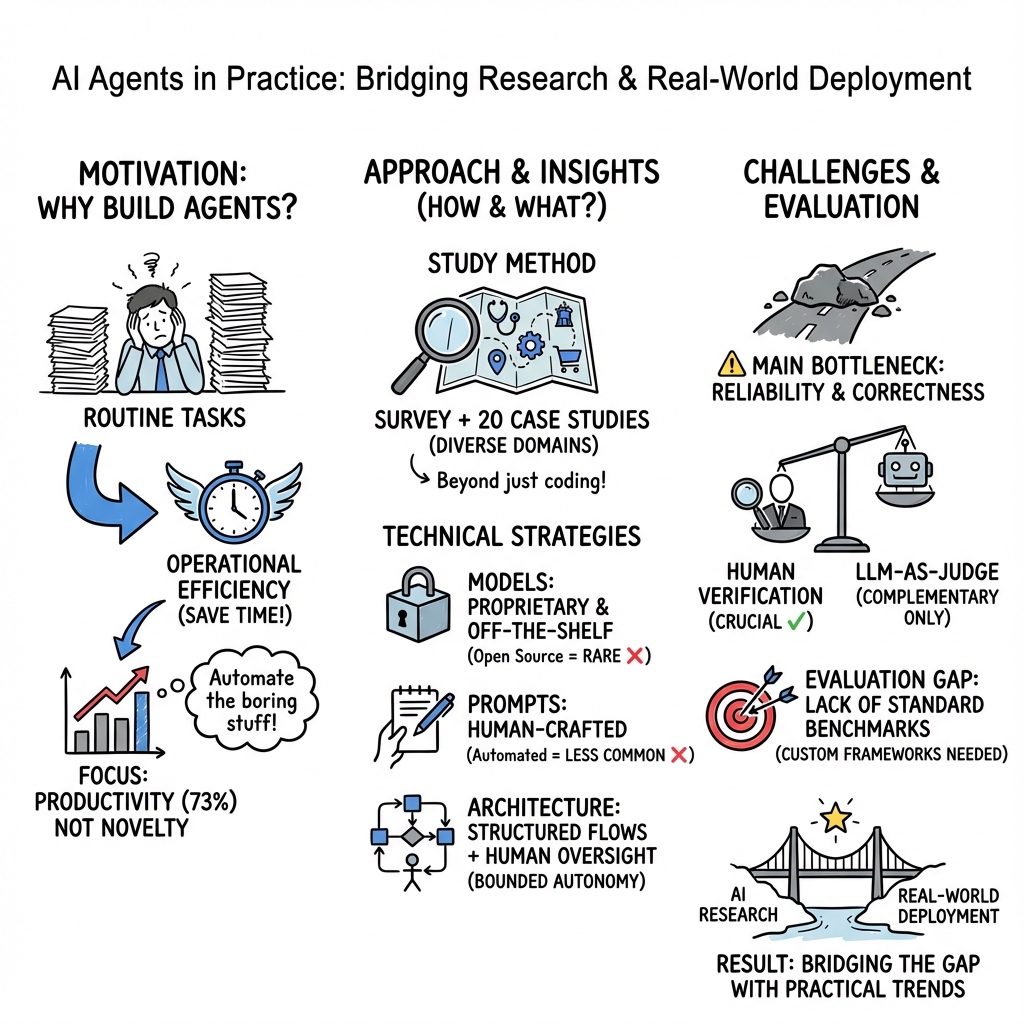

Abstract: AI agents are actively running in production across diverse industries, yet little is publicly known about which technical approaches enable successful real-world deployments. We present the first large-scale systematic study of AI agents in production, surveying 306 practitioners and conducting 20 in-depth case studies via interviews across 26 domains. We investigate why organizations build agents, how they build them, how they evaluate them, and what the top development challenges are. We find that production agents are typically built using simple, controllable approaches: 68% execute at most 10 steps before requiring human intervention, 70% rely on prompting off-the-shelf models instead of weight tuning, and 74% depend primarily on human evaluation. Reliability remains the top development challenge, driven by difficulties in ensuring and evaluating agent correctness. Despite these challenges, simple yet effective methods already enable agents to deliver impact across diverse industries. Our study documents the current state of practice and bridges the gap between research and deployment by providing researchers visibility into production challenges while offering practitioners proven patterns from successful deployments.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper looks at how “AI agents” are actually used in the real world today. An AI agent is like a smart software helper that can read instructions, use tools, remember things, and take several steps to finish a task with little or no supervision. The authors wanted to know what makes these agents work well in real companies, not just in lab demos.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The study focused on four simple questions:

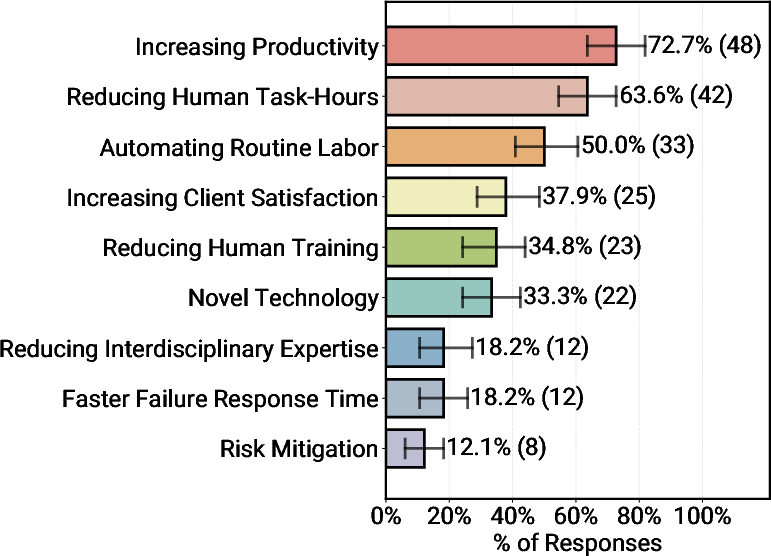

- What kinds of jobs do AI agents do, who uses them, and what do those users need?

- How are these agents built (which models, designs, and techniques)?

- How do teams check that agents work correctly before and after deployment?

- What are the biggest problems developers face when putting agents into real use?

How they studied it

To get a realistic picture, the authors did two things:

- They analyzed survey answers about 86 agent systems that were already deployed (live with real users or in pilot tests).

- They ran 20 in‑depth interviews (case studies) with teams that built and run these agents, across many industries (like finance, software operations, science, and customer support).

Some terms in everyday language:

- Production: the agent is used by real people on real tasks, not just a school project or a lab experiment.

- Prompting: giving the AI very clear instructions and examples, like telling a new coworker exactly how to do a task.

- Fine‑tuning: retraining the AI on extra data so it learns a new skill—like sending that coworker to a special class.

- Human‑in‑the‑loop: a person checks or approves the AI’s work, especially for important steps.

- LLM‑as‑a‑judge: using another AI to quickly grade or review the first AI’s output—like a second opinion—but it’s not a full replacement for human checks.

- Latency: how long the agent takes to respond.

What they found (and why it matters)

Here are the main takeaways the authors highlight, explained simply:

- Productivity is the big reason companies use agents.

- About three‑quarters of teams said the top benefit is saving time and speeding up work. Even if an agent takes a few minutes to answer, that can still be much faster than a person doing the same task by hand.

- Most agents help humans directly.

- Over 90% of deployed agents serve people (often company employees). This makes it easier to keep a human in the loop to review or fix the agent’s work.

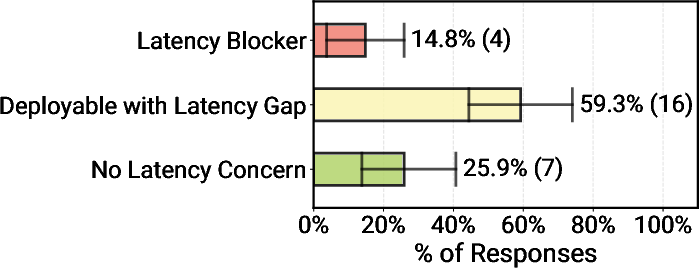

- Speed is usually “minutes,” not instant.

- Many real‑world tasks don’t need split‑second responses. Teams often allow response times of minutes because the agent still finishes much faster than a person would.

- Simple, controlled designs work best today.

- About 68% of agents do at most 10 steps before asking a human for help. Nearly half do fewer than 5 steps. This is like keeping your robot helper on a short leash so it doesn’t wander off or make big mistakes.

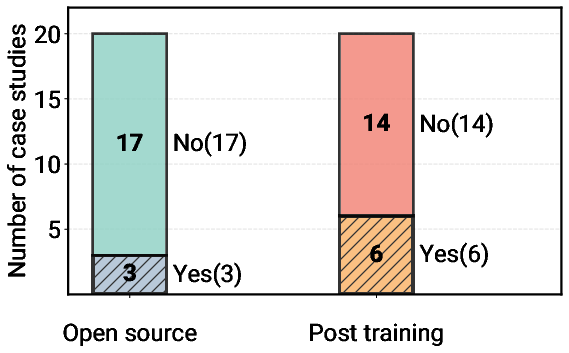

- Around 70% rely on carefully written prompts with off‑the‑shelf models instead of retraining the AI. In practice, clear instructions plus a strong base model go a long way.

- Many teams skip third‑party “agent frameworks” and just build the parts they need. Simpler systems are easier to understand and control.

- Human checks are still essential.

- About 74% mainly evaluate their agents with human reviewers. Around half also use “AI judges,” but teams that do this still keep humans in the loop for safety and correctness.

- Public benchmarks (standard tests) often don’t match a company’s specific tasks, so about a quarter of teams build their own tests; many others rely on A/B tests and expert feedback.

- Reliability is the hardest problem.

- The biggest challenge is making sure the agent is correct, consistent, and safe. That’s why teams prefer tight controls, smaller task scopes, and human oversight.

- Latency (being fast) blocks deployment only for a small slice of use cases that truly need real‑time interaction (like voice assistants).

- Security is handled mainly by limiting what the agent can do and what data it can access.

- Model choices are practical, not flashy.

- Many teams use the strongest proprietary (closed‑source) models available because, compared to human time, the model cost is worth it for better results.

- Open‑source models are used mainly when costs must be very low at huge scale or when strict rules prevent sending data to external providers.

- Some agents mix multiple models to balance cost and quality or to handle different types of data (like text-to-speech for phone systems).

In short: companies get the most success by keeping agents focused, controllable, and supervised. Fancy, fully autonomous mega‑agents are not how most real systems work today.

What this means going forward

- For builders: Start simple, set clear limits, and include human checks. Focus on writing excellent prompts, choose reliable models, and keep workflows short and understandable. Measure what matters for your task (accuracy and usefulness), not just what’s easy to measure.

- For researchers: The biggest gap is reliability and evaluation. Better ways to test and verify agent correctness—especially on company‑specific tasks—would help a lot. Tools that improve controllability and safe autonomy, without making systems overly complex, are also valuable.

- For everyone: Even with today’s limits, well‑designed, well‑supervised agents already save people a lot of time across many industries. The path to impact right now is practical and careful, not flashy—think smart assistant with guardrails, not a free‑running robot.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research and engineering work:

- Sampling and survivorship bias: The study deliberately focuses on production and pilot systems and experienced teams, likely overrepresenting successful deployments and underrepresenting failures; a complementary analysis of failed or abandoned agent projects is missing.

- Recruitment bias: Distribution via specific events and networks (e.g., Berkeley RDI, AI Alliance) may skew the sample toward certain geographies, sectors, and technical cultures; the representativeness of the population of “agents in production” is unclear.

- Unresolved sample sizes and transparency: Key counts appear as placeholders (e.g., numresponse, numcase, numdomain), preventing independent assessment of statistical power and generalizability.

- Lack of longitudinal evidence: Findings are from a time-bounded, cross-sectional snapshot (July–Oct 2025); how practices, performance, and reliability evolve over time, with model version changes and organizational learning, is unknown.

- Limited quantitative effect sizes: The paper emphasizes perceived productivity gains; standardized, task-level, controlled measurements (e.g., A/B tests with power analysis, randomized controlled trials, pre-post studies) quantifying effect sizes are not reported.

- External validity across domains: Although many domains are mentioned, the depth of domain-specific performance and constraints (e.g., healthcare, legal, finance) is not analyzed; transferability of practices across regulated and safety-critical settings remains open.

- Generalizability to consumer-facing and real-time contexts: Most systems serve internal users and tolerate minute-level latency; how the reported practices translate to external, consumer-facing, high-volume, and real-time interactive applications (e.g., voice agents) is not established.

- Underexplored failure modes: A taxonomy and incidence rates of agent failures (e.g., correctness errors, tool misuse, escalation failures, hallucination-induced actions) and causal root analyses are absent.

- Reliability measurement gaps: Concrete operational reliability metrics (e.g., task success rates, mean time between critical failures, escalation efficacy, action-level error rates) and monitoring practices are not specified.

- Evaluation standardization: With bespoke tasks and human-in-the-loop (HITL) evaluation prevalent, methods to create reliable, reusable, domain-specific benchmarks and gold standards (including privacy-preserving or synthetic data approaches) remain open.

- LLM-as-a-judge calibration: Conditions under which LLM-based judges correlate with expert assessments, fail systematically, or can be robustly calibrated/validated in domain-specific tasks are not addressed.

- Human-in-the-loop design and costs: The paper does not quantify human verification burden, cognitive load, failure detection sensitivity/specificity, escalation UX, or total cost of ownership (TCO) for sustained HITL operations.

- Latency–quality trade-offs: Systematic methods for optimizing quality under strict latency constraints (e.g., streaming reasoning, early-exit policies, progressive results) are not characterized for real-time use cases.

- Tool use and memory best practices: Concrete guidance and measurements for tool selection, function-calling reliability, state/memory management (context growth, retrieval quality, forgetting), and their impact on correctness and cost are not provided.

- Prompt engineering at production scale: While long prompts (>10k tokens) are reported, the costs, maintenance burden, brittleness to model updates, drift over time, and governance of prompt changes remain unquantified.

- Model migration and versioning risks: Formal methods and metrics for safe model updates (canarying, rollback policies, behavioral regression detection, compatibility contracts) are not articulated despite observed multi-model/multi-version realities.

- Open-source vs proprietary trade-offs: Beyond anecdotal drivers (cost, regulation), a rigorous comparison of quality, security, data governance, TCO, and maintainability across open vs closed models is missing.

- Fine-tuning and RL in production: Criteria for when SFT/RL is ROI-positive, data requirements, safety constraints, and operational pipelines for model updates are not examined.

- Cost accounting and scaling economics: Detailed TCO models (inference, context costs, HITL labor, monitoring, guardrails, incidence response) and scalability analyses for high-throughput settings are absent.

- Security and safety quantification: The paper treats security as “manageable,” but lacks systematic measurements or methodologies for threat modeling, attack incidence (prompt injection, toolchain compromise), red teaming protocols, and guardrail efficacy.

- Governance and compliance in regulated sectors: Concrete practices for auditability (action logs, data lineage), data residency, consent, retention policies, and third-party vendor risk management for agent workflows are not specified.

- Observability and MLOps for agents: Standard operating procedures and tooling for agent observability (traceability, event logs, action graphs), evaluation in production, drift detection, and SLO-based incident response are not detailed.

- Autonomy vs control trade-offs: Formal frameworks to tune and verify autonomy (step limits, termination conditions, escalation triggers) and to quantify error accumulation with increasing step counts are not provided.

- Multi-agent systems: The study does not analyze multi-agent coordination patterns, conflict resolution, communication protocols, or their reliability and evaluation challenges.

- Multimodality coverage: Integration strategies, evaluation, and reliability for speech, vision, and domain-specific modalities (e.g., chemistry models) are underexplored beyond anecdotal mentions.

- Human factors and organizational change: Effects on roles, trust, training needs, automation bias, accountability, and division of labor between agents and experts are not studied.

- Definition ambiguity: The survey allows self-identified “agentic” systems; without a consistent operational definition, heterogeneity may confound comparisons and recommendations.

- Replicability of qualitative findings: Interview coding procedures, inter-rater reliability, and availability of de-identified artifacts are not described, limiting reproducibility.

- Data and code availability: It is unclear whether cleaned survey data, analysis code, and categorization mappings (e.g., LOTUS domain normalization) will be released to enable independent verification and extension.

- Temporal robustness of conclusions: Given rapid model advances, how resilient these practice patterns are to new capabilities (e.g., better reasoning, lower latency) is unknown; planned follow-up waves or continuous measurement are not described.

Glossary

- A/B testing: A randomized experimental method that compares two variants (A and B) to measure which performs better on a defined metric. "relying instead on online-tests such as A/B testing or direct expert/user feedback."

- agent autonomy: The degree to which an AI agent can make decisions and act without human intervention. "Organizations deliberately constrain agent autonomy to maintain reliability."

- Agentic AI: AI systems that plan, decide, and act—often using tools and memory—to accomplish multi-step tasks with some independence. "Application domains where practitioners build and deploy Agentic AI systems ()."

- bootstrap samples: Resampled datasets created by sampling with replacement from the original data, used to estimate uncertainty such as variances or intervals. "Error bars indicate 95th-percentile intervals estimated from 1{,}000 bootstrap samples with replacements."

- closed-source frontier models: Proprietary, top-performing AI models whose parameters and training data are not publicly released. "the remaining 17 rely on closed-source frontier models (Figure~\ref{fig:model_openness_adaptation})."

- confidence intervals: Statistical ranges that, with a specified confidence level, are believed to contain the true value of an estimated parameter. "we report 95% confidence intervals computed using 1{,}000 bootstrap samples with replacement."

- data modalities: Different types or forms of data (e.g., text, audio, images) that systems process. "to handle distinct data modalities."

- dynamic branching logic: A survey design where which questions appear depends on prior answers, tailoring the flow to respondents. "we implemented the survey with dynamic branching logic in Qualtrics"

- end-to-end latency: The total time from initiating a request to receiving the final response, including all processing steps. "maximum allowable end-to-end latency."

- evaluation suites: Curated collections of tests, metrics, and procedures used to assess system performance. "agent scaffolds and evaluation suites"

- foundation models: Large models pre-trained on broad data that can be adapted to many downstream tasks. "combine foundation models with optional tools, memory, and reasoning capabilities"

- frontier models: The most capable, cutting-edge models available at a given time. "select the most capable, expensive frontier models available"

- governance policies: Organizational rules and controls that constrain how models and data are used to meet compliance and risk requirements. "governance policies enforce teams to route subtasks to different model endpoints"

- human baselines: Performance metrics obtained from human workers used as a benchmark for comparing AI systems. "compared to human baselines."

- human-in-the-loop evaluation: An assessment approach where humans review and validate system outputs, often for quality or safety. "rely primarily on human-in-the-loop evaluation"

- LLMs: Very large neural LLMs (often transformer-based) trained on massive text corpora to perform diverse language tasks. "LLMs have enabled a new class of software systems: AI Agents."

- LLM-as-a-judge: Using a LLM to automatically evaluate or score outputs from systems or other models. "52% use LLM-as-a-judge"

- LOTUS: A tool for processing and normalizing unstructured text data into structured forms. "we used LOTUS, a state-of-the-art unstructured data processing tool"

- model endpoints: API-accessible deployment points that serve specific model versions for inference. "route subtasks to different model endpoints"

- model migration: The process of replacing or upgrading a deployed model with a new version and managing behavioral changes. "to manage agent's behavioral shifts from model migration."

- multi-class classification: A classification task with more than two possible classes for each example. "multi-class classification question"

- off-the-shelf models: Pretrained models used as-is (without modifying weights), typically accessed via APIs. "rely on prompting off-the-shelf models instead of weight tuning"

- phased rollout: Gradual deployment of a system to increasing user groups to monitor performance and manage risk. "for evaluation, phased rollout, or safety testing."

- pilot systems: Limited deployments to controlled user groups used for evaluation prior to full production. "Pilot systems are deployed to controlled user groups for evaluation, phased rollout, or safety testing."

- post-training: Any training performed after pretraining (e.g., fine-tuning or reinforcement learning) to specialize a model. "post-training (e.g. fine-tuning, reinforcement learning)"

- production systems: Fully deployed systems serving intended end users in live operational environments. "Production systems are fully deployed and used by target end users in live operational environments."

- prompt construction: The process of crafting inputs (prompts) to elicit desired behavior from LLMs. "manual prompt construction"

- reinforcement learning (RL): A learning paradigm where agents learn by interacting with an environment and receiving reward signals. "reinforcement learning (RL)"

- semi-structured interview protocol: An interview approach guided by a predefined outline while allowing flexible follow-ups and probing. "We followed a semi-structured interview protocol"

- state-of-the-art models: The best-performing models known in the field at a given time. "test the top accessible state-of-the-art models"

- supervised fine-tuning (SFT): Training a pretrained model on labeled task-specific data to adapt it to a particular domain or behavior. "supervised fine-tuning (SFT)"

- text-to-speech: Technology that converts written text into spoken audio. "text-to-speech"

- third-party agent frameworks: External libraries/platforms that provide scaffolding and orchestration features for building agents. "forgo third-party agent frameworks"

- unstructured data processing: Techniques for analyzing and organizing data lacking a predefined schema, such as free-form text. "a state-of-the-art unstructured data processing tool"

- weight tuning: Updating a model’s parameters through additional training to change or improve its behavior. "instead of weight tuning"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a curated set of deployable use cases that align with the paper’s findings (simple, controllable agent workflows; off-the-shelf LLMs; human-in-the-loop evaluation; relaxed latency). Each item lists sector linkages, likely tools/workflows, and feasibility assumptions.

- Internal HR and policy assistant for enterprises

- Sectors: corporate services, HR software

- Tools/workflows: Slack/Teams bot; RAG over internal policies; role-based access; audit logging

- Assumptions/Dependencies: clean and indexed knowledge base; access controls; human approval gates

- Insurance claims triage and document extraction

- Sectors: insurance, healthcare administration

- Tools/workflows: OCR/PDF parsing; coverage checks; BPM/workflow engines; human adjudication step

- Assumptions/Dependencies: structured forms; compliance reviews; data redaction; minutes-level latency accepted

- Customer care agent copilot (internal-facing)

- Sectors: customer support, CRM

- Tools/workflows: Salesforce/Zendesk integration; case history retrieval; templated drafting; guardrails

- Assumptions/Dependencies: PII governance; human-in-the-loop response approval; domain-specific prompts

- SRE/Incident response assistant

- Sectors: software/devops

- Tools/workflows: PagerDuty/Datadog hooks; log/event summarization; runbook suggestion; ticket pre-fill

- Assumptions/Dependencies: observability connectors; sandboxed actions; minutes-level latency tolerated; on-call engineer oversight

- Codebase modernization and SQL optimization

- Sectors: software development, data engineering

- Tools/workflows: IDE plugins (VSCode, JetBrains); CI bots for diffs; linters/test harnesses; static analysis

- Assumptions/Dependencies: adequate test coverage; repository access; human code review gates

- Enterprise analytics copilot (query-to-dashboard)

- Sectors: data analytics, BI

- Tools/workflows: translation from business question to SQL; safe DB proxy/sandbox; PowerBI/Tableau integration

- Assumptions/Dependencies: semantic layer/data catalog; RBAC; custom evaluation via A/B testing; human validation

- Materials safety and regulatory summary generator

- Sectors: manufacturing, HSE compliance

- Tools/workflows: multi-document ingestion; ontology mapping; summary templates; expert sign-off

- Assumptions/Dependencies: up-to-date regulatory sources; domain evaluation; traceable citations

- Multilingual communication drafting and scheduling

- Sectors: communications, automotive services

- Tools/workflows: translation + TTS; CRM/channel APIs (Twilio); brand style prompts; content moderation

- Assumptions/Dependencies: consent and rate limits; human approval; latency in seconds to minutes acceptable

- Biomedical research workflow assistant

- Sectors: life sciences R&D

- Tools/workflows: ELN integrations; reagent/protocol knowledge bases; literature retrieval; provenance logging

- Assumptions/Dependencies: subscription literature access; domain review; controlled lab context

- Legal/finance diligence summarization

- Sectors: finance, legal services

- Tools/workflows: EDGAR/API ingestion; PDF parsing; anomaly flagging; analyst review workflow

- Assumptions/Dependencies: confidentiality safeguards; custom scoring rubrics; human-in-the-loop sign-off

- Education virtual TA (teacher-supervised)

- Sectors: education

- Tools/workflows: LMS plugins (Canvas/Moodle); rubric-based feedback; structured Q&A; usage analytics

- Assumptions/Dependencies: course content ingestion; fairness guardrails; instructor approval

- Reliability-first agent refactoring (simplify autonomy)

- Sectors: software/product teams (cross-industry)

- Tools/workflows: replace long, stochastic loops with 5–10 step static workflows; stage gates; checklists

- Assumptions/Dependencies: stakeholder buy-in; measurable quality criteria; change management

- Human-in-the-loop evaluation pipeline

- Sectors: all deploying organizations

- Tools/workflows: labeling UIs; logging + replay; LLM-as-judge as secondary; online A/B testing

- Assumptions/Dependencies: expert availability; custom, task-specific metrics; data governance

- Governance and guardrails for agent action spaces

- Sectors: enterprise IT, compliance

- Tools/workflows: tool whitelists; sandbox environments; API proxies; policy-as-code; audit trails

- Assumptions/Dependencies: security team alignment; model provider terms; clear escalation paths

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities likely require stronger correctness guarantees, tighter latency, broader autonomy, new benchmarks/certifications, or scaled MLOps. Each item lists sector linkages, potential products/workflows, and feasibility constraints.

- End-to-end autonomous claims settlement

- Sectors: insurance

- Tools/workflows: full pipeline agents (intake → validation → adjudication → payout); exception handling

- Assumptions/Dependencies: robust correctness and appeals workflows; regulatory approval; formal evaluations

- Real-time clinical triage voice agents

- Sectors: healthcare

- Tools/workflows: <1s ASR/TTS; clinical reasoning; EHR tool use; handoff to clinicians

- Assumptions/Dependencies: safety validation; liability frameworks; high-accuracy speech + medical NLU

- Autonomous scientific discovery with lab robots

- Sectors: pharmaceuticals, materials science

- Tools/workflows: experiment design → robotic execution → analysis → next-step planning; provenance + safety

- Assumptions/Dependencies: physical automation; closed-loop validation; domain-specific models; biosafety compliance

- Banker-grade external agents for transactions and fraud checks

- Sectors: retail/enterprise banking

- Tools/workflows: KYC integration; transaction execution; real-time fraud screening; customer-facing UX

- Assumptions/Dependencies: auditable reliability; security certifications; regulator-defined guardrails

- Autonomous software maintenance and deployment

- Sectors: software/devops

- Tools/workflows: plan → code → test → deploy → observe; formal verification; progressive rollouts

- Assumptions/Dependencies: very high test coverage; rollback mechanisms; stronger reasoning; organizational change management

- Sector-specific agent correctness benchmarks and certification

- Sectors: policy/compliance; cross-industry

- Tools/workflows: ISO-like standards; “agent bill of materials”; third-party audits; longitudinal reliability metrics

- Assumptions/Dependencies: multi-stakeholder consensus; regulator adoption; public test suites

- Cost-optimized open-source agent stacks at scale

- Sectors: high-volume operations (support, back-office)

- Tools/workflows: fine-tuned OSS LLMs; internal GPU clusters; domain adapters; model lifecycle tooling

- Assumptions/Dependencies: MLOps maturity; data pipelines; responsible model updates; TCO analysis

- Scalable human oversight with selective review and risk scoring

- Sectors: enterprises scaling agents

- Tools/workflows: gating via LLM-as-judge; active learning; triage queues; feedback loops into prompts/models

- Assumptions/Dependencies: high-quality logging; labeling budgets; bias/selection management

- Cross-model migration control plane

- Sectors: organizations using multiple LLMs/providers

- Tools/workflows: per-task routing; regression testing; canary deployments; change control dashboards

- Assumptions/Dependencies: observability; evaluation suites; provider SLAs; governance policies

- Personalized curriculum planners and outcome tracking

- Sectors: education

- Tools/workflows: multi-course planning; adaptive content; teacher dashboards; fairness audits

- Assumptions/Dependencies: longitudinal data; equity safeguards; district/state approvals

- Continuous regulatory monitoring and workflow reconfiguration

- Sectors: finance, healthcare, manufacturing

- Tools/workflows: machine-readable regulation feeds; automated prompt/workflow updates; compliance traceability

- Assumptions/Dependencies: standardized legal data; governance councils; change-management processes

- Energy grid operations copilot → eventual autonomous dispatch

- Sectors: energy/utilities

- Tools/workflows: demand response planning; simulation; operator-in-the-loop; gradual autonomy

- Assumptions/Dependencies: grid safety constraints; certification; integration with SCADA systems

- Household/industrial embodied agents

- Sectors: robotics, manufacturing

- Tools/workflows: tool-use planning; multimodal perception; safety envelopes; human handoff

- Assumptions/Dependencies: robust embodied models; reliable hardware; stringent safety standards

- Portfolio research to compliant trade execution

- Sectors: asset management

- Tools/workflows: research → risk checks → trade proposals → execution; audit trails; supervision

- Assumptions/Dependencies: compliance regimes; risk controls; market impact analysis; strong correctness guarantees

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- The study’s evidence supports starting with constrained environments, short agent workflows (≤5–10 steps), off-the-shelf models, manual prompts, minutes-level latency, and human-in-the-loop evaluation.

- Production success hinges on domain-specific evaluation, custom metrics/benchmarks, and rigorous governance.

- Open-source stacks become viable at scale with sufficient MLOps capability; otherwise, proprietary frontier models often dominate due to performance and lower effective cost versus human baselines.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.