- The paper introduces Temporal Sampling to counter temporal forgetting by aggregating outputs from multiple training checkpoints.

- It quantifies performance loss with metrics like Lost Score and Temporal Forgetting Score, showing improvements of 4–19 percentage points on benchmarks.

- The approach employs resource-efficient techniques such as LoRA, enabling enhanced reasoning without extra retraining or ensembling.

Temporal Sampling for Forgotten Reasoning in LLMs

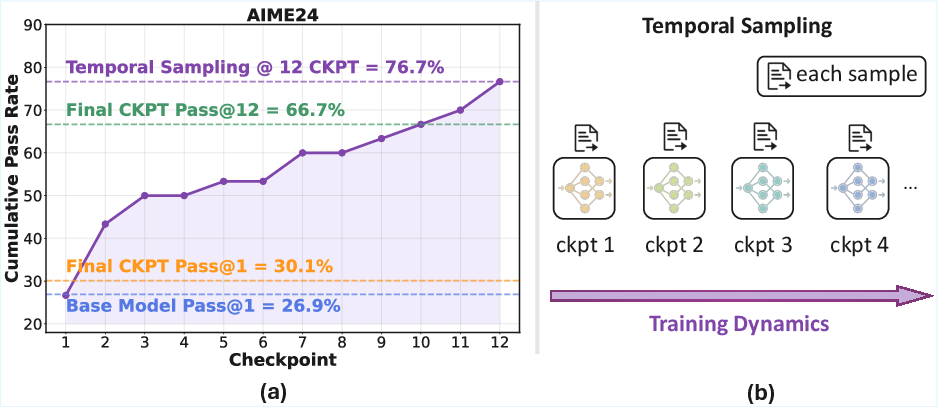

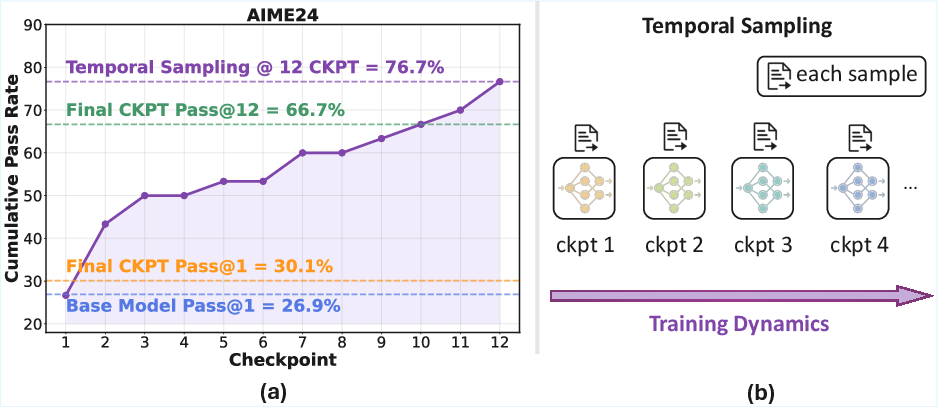

The paper "Temporal Sampling for Forgotten Reasoning in LLMs" (2505.20196) introduces the concept of Temporal Forgetting in LLMs, where models forget solutions to problems they previously solved correctly during fine-tuning. To address this, the paper proposes Temporal Sampling, a decoding strategy that leverages multiple checkpoints along the training trajectory to improve reasoning performance.

Identifying Temporal Forgetting

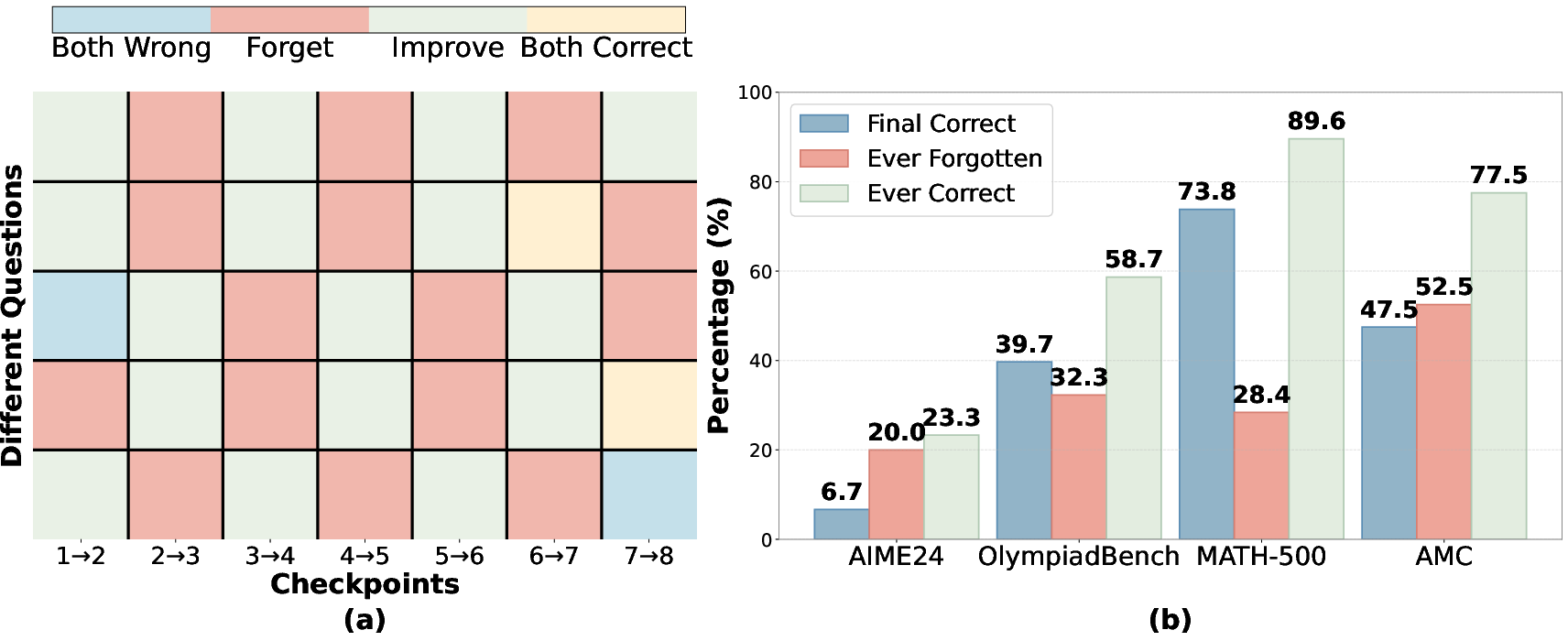

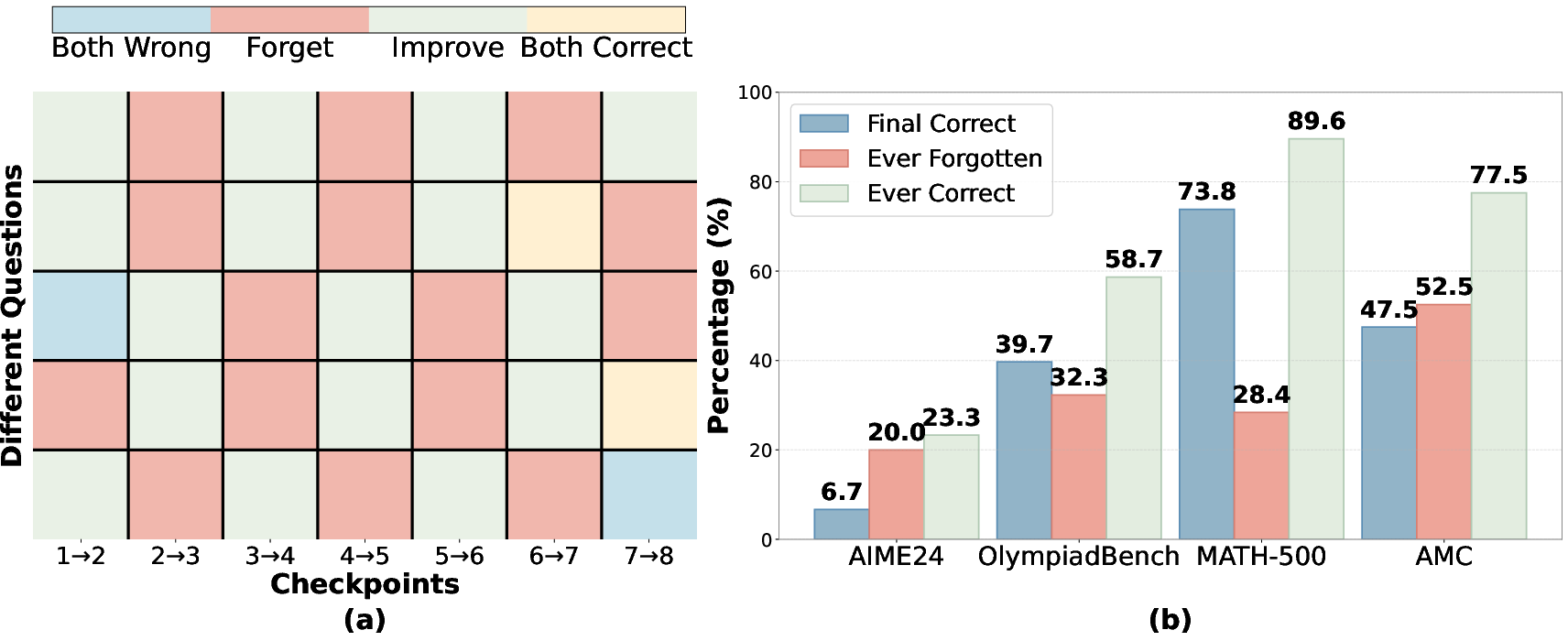

The paper begins by highlighting a key observation: fine-tuning can lead to a decrease in performance on specific problems that the base model already solved correctly. This phenomenon is quantified using the Lost Score (PLost), which measures the percentage of questions answered correctly by the base model but incorrectly by the fine-tuned model. The authors demonstrate that PLost can range from 6.1\% to 16.0\% across various SOTA models and benchmarks, indicating that overall performance improvements may mask underlying losses in specific reasoning capabilities.

Figure 1: (a) We observed that during RL training process of Deepseek-R1-1.5B model, 76.7\% of AIME problems were solved correctly at some intermediate checkpoint, yet only 30\% remained correct in the final model. We term this phenomenon as Temporal Forgetting. (b) We proposed Temporal Sampling: This method utilizes training dynamics as a source of answer diversity by distributing inference samples across multiple distinct checkpoints from the training trajectory, rather than relying solely on the single final checkpoint.

To further investigate this, the authors introduce the Ever Correct Score (PECS) and the Temporal Forgetting Score (PTFS). PECS represents the percentage of questions answered correctly by at least one checkpoint during fine-tuning, while PTFS measures the percentage of questions answered correctly by some checkpoint but incorrectly by the final checkpoint. Their analysis reveals that PTFS can range from 6.4\% to 56.1\%, suggesting a significant degree of "forgetting" during the training process. The paper illustrates that Temporal Forgetting focuses on changes in correctness at the individual question level, rather than on a collective measure, thus cannot be directly captured by the overall performance score only.

Figure 2: Forgetting dynamics of Qwen2.5-7B during RL training. (a) Answer correctness trajectories for OlympiadBench questions across training checkpoints, illustrating solutions oscillate between correct and incorrect states. "Forget" implies that an answer was correct at the previous checkpoint but incorrect at the current one. Conversely, "Improve" implies that an answer that was incorrect at the previous checkpoint but correct at the current one. (b) Percentage of questions per benchmark that are ever forgotten or ever correct at some checkpoint during GRPO.

Temporal Sampling Methodology

Inspired by these observations, the paper introduces Temporal Sampling. This approach involves sampling completions from multiple checkpoints along the training trajectory, rather than relying solely on the final checkpoint. By distributing the sampling budget across time, Temporal Sampling aims to recover forgotten solutions without retraining or ensembling.

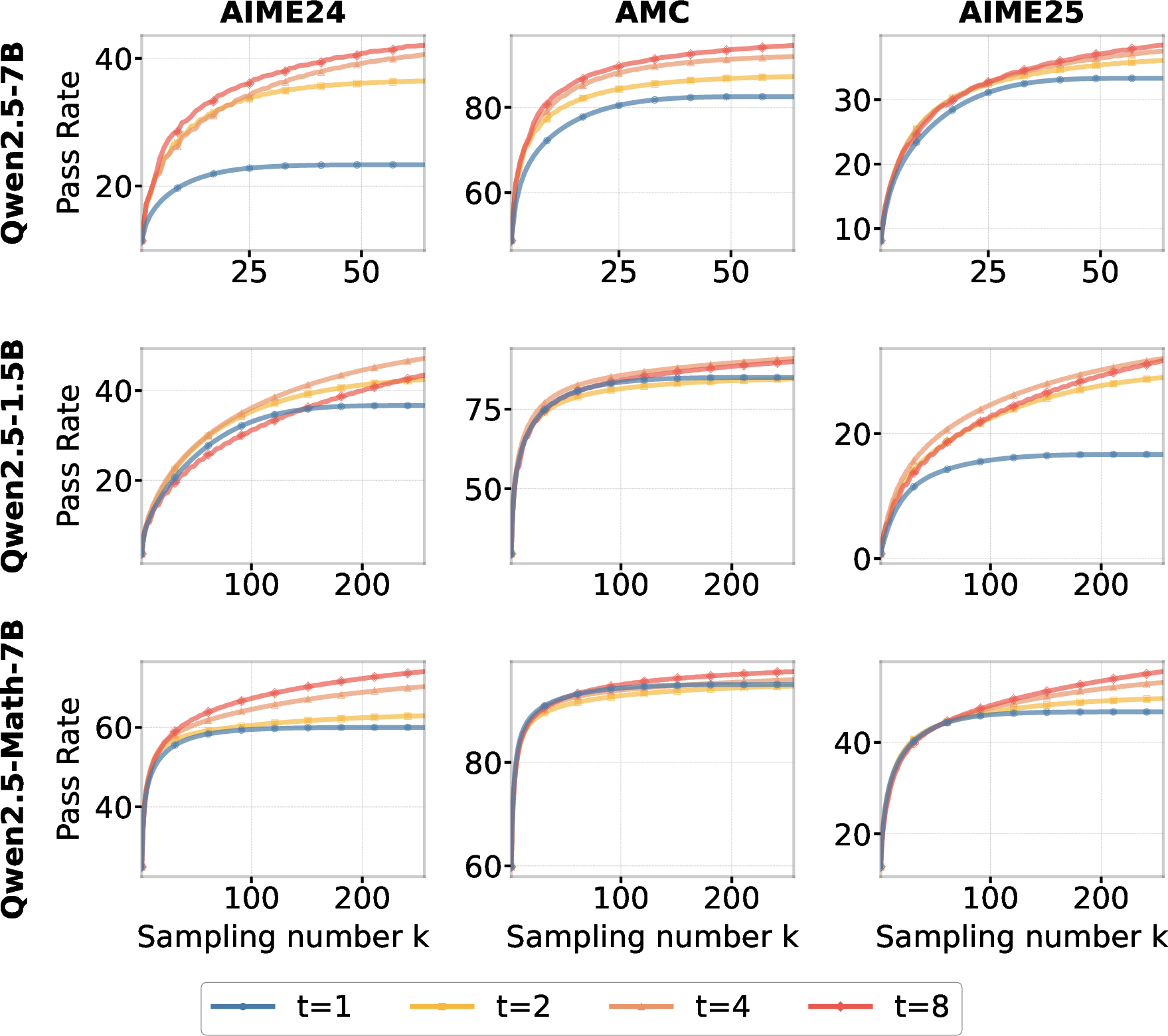

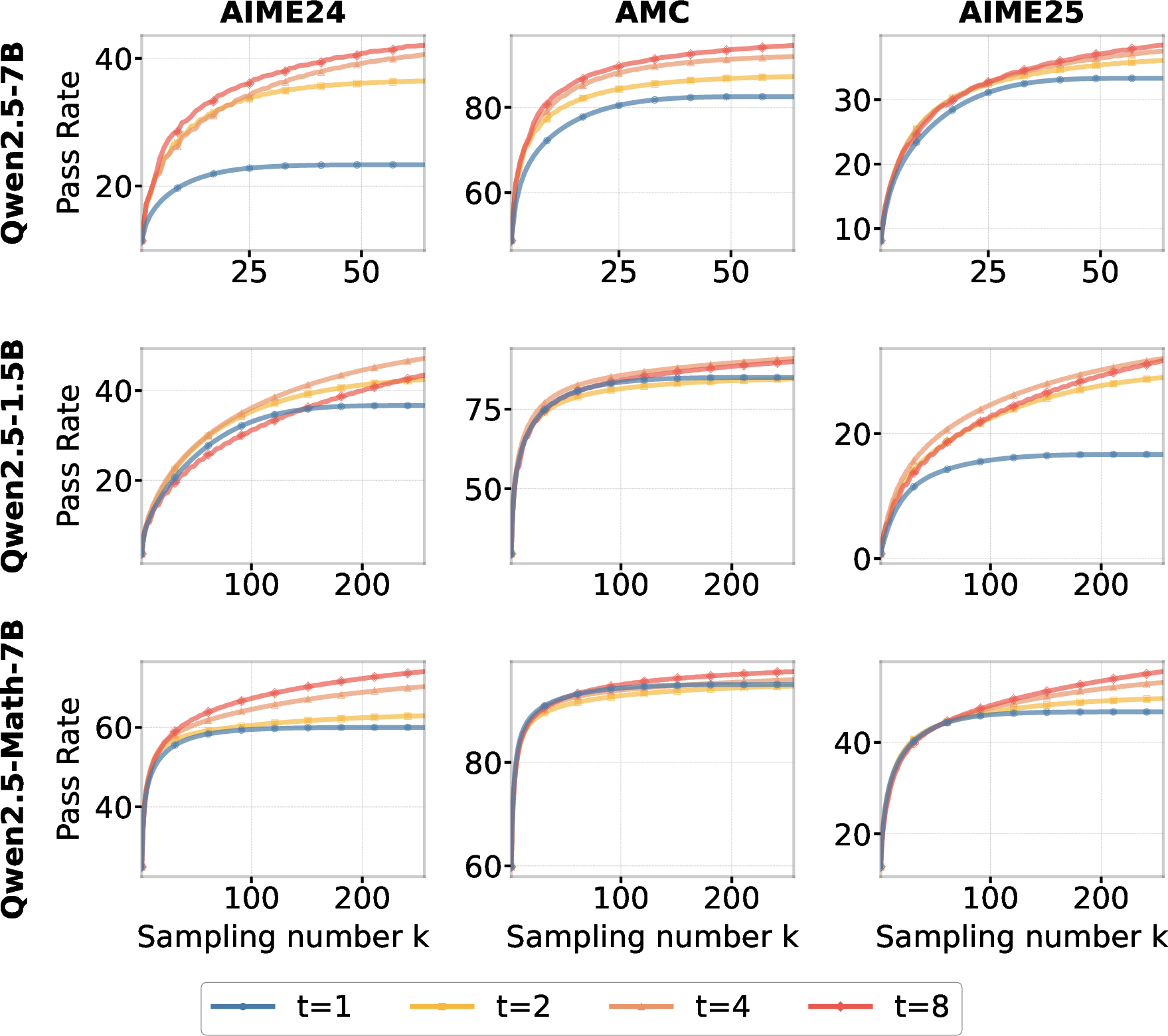

To evaluate the efficacy of Temporal Sampling, the paper introduces the metric Pass@k∣t, which measures the probability of obtaining at least one correct answer when k samples are drawn from t checkpoints. The authors employ a round-robin allocation strategy to distribute sampling attempts among checkpoints.

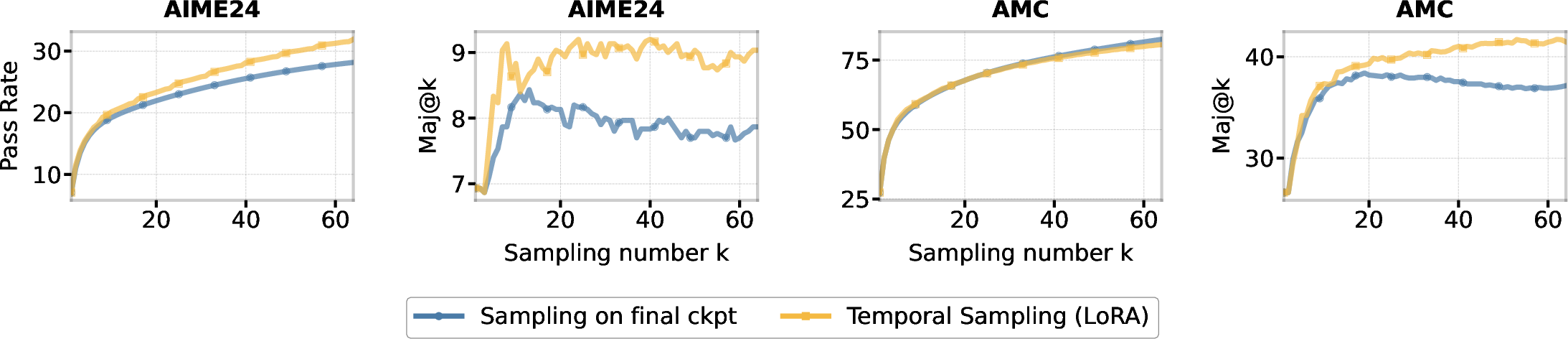

The experimental results demonstrate that Temporal Sampling consistently outperforms the baseline of sampling only from the final checkpoint. Across benchmarks such as AIME2024, AMC, and AIME2025, Temporal Sampling achieves gains of 4 to 19 points in Pass@k compared to final-checkpoint-only sampling. The authors also demonstrate that Temporal Sampling enhances the performance of majority voting (Maj@k) and Best-of-N (BoN) decoding. At k=64, Maj@k∣8 achieves an accuracy exceeding 21, substantially outperforming the 13\% accuracy of the baseline. With Best-of-N (BoN) decoding, Temporal Sampling with t=8 checkpoints significantly outperforms the baseline (t=1), achieving improvements of more than 7, 8, and 1 percentage points across the three benchmarks when sampling k=64 responses.

Figure 3: Pass@k for different numbers of checkpoints t on the AIME2024, AMC, and AIME2025 benchmarks when using Temporal Sampling. The case t=1 represents the baseline of standard Pass@k sampling on the final checkpoint. Our proposed Temporal Sampling for Qwen2.5-7B with t=8 outperforms the baseline by more than 19, 13, and 4 percentage points on AIME2024, AMC, and AIME2025, respectively, when sampling 64 responses.

The paper compares Temporal Sampling against a Mixture of Models (MoM) approach, which combines outputs from different foundation models. The results show that Temporal Sampling achieves higher sampling performance than the MoM approach under the same computational budget.

Deployment Considerations

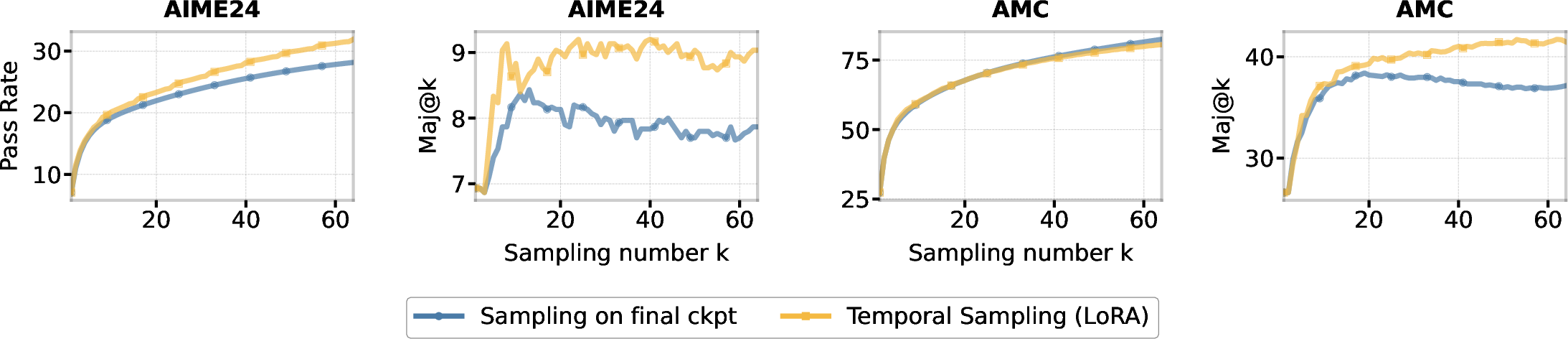

To address the storage costs associated with saving multiple model checkpoints, the paper explores the use of LoRA for fine-tuning. The authors demonstrate that Temporal Sampling implemented with LoRA checkpoints outperforms sampling only from the final checkpoint for both Pass@k and Maj@k metrics. This suggests that Temporal Sampling can be deployed in resource-constrained settings with minimal performance degradation.

Figure 4: Performance of Temporal Sampling using 8 checkpoints from LoRA SFT of Qwen2.5-7B. Results on the AIME24 and AMC demonstrate that Temporal Sampling with LoRA checkpoints surpasses the baseline (sampling only from the final checkpoint) for both Pass@k and Maj@k.

Conclusion

The paper presents compelling evidence for the existence of Temporal Forgetting in LLMs and proposes Temporal Sampling as an effective strategy to mitigate this issue. By leveraging the diversity inherent in training dynamics, Temporal Sampling offers a practical and compute-efficient way to improve reasoning performance. The findings suggest that true model competence may not reside in a single parameter snapshot, but rather in the collective dynamics of training itself. Future work may explore methods to transfer the performance gains from Pass@k∣t to Pass@1∣1 and develop a more comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding learning and forgetting dynamics.