2000 character limit reached

LLMs Simulate Big Five Personality Traits: Further Evidence

Published 31 Jan 2024 in cs.CL and cs.AI | (2402.01765v1)

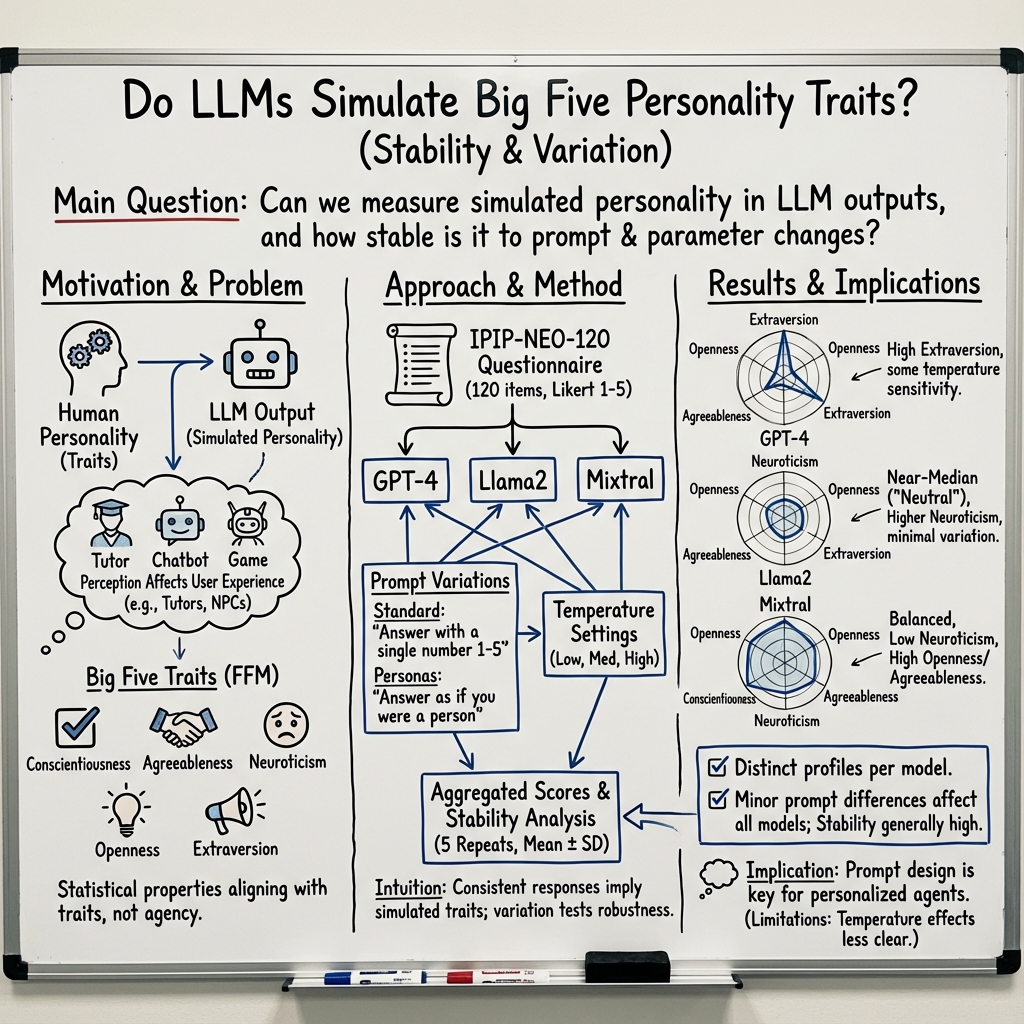

Abstract: An empirical investigation into the simulation of the Big Five personality traits by LLMs, namely Llama2, GPT4, and Mixtral, is presented. We analyze the personality traits simulated by these models and their stability. This contributes to the broader understanding of the capabilities of LLMs to simulate personality traits and the respective implications for personalized human-computer interaction.

- When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2307.16376.

- The convergent validity between self and observer ratings of personality: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 15(1):110–117.

- David C. Funder and C. Randall Colvin. 1997. Congruence of others’ and self-judgments of personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology, pages 617–647. Elsevier.

- GenAI and Meta. 2023. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2307.09288v2.

- Accuracy of judging others’ traits and states: Comparing mean levels across tests. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6):1476–1489.

- Evaluating and inducing personality in pre-trained language models. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2206.07550v3.

- P.J. Kajonius and J.A. Johnson. 2019. Assessing the structure of the five factor model of personality (IPIP-NEO-120) in the public domain. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(2).

- Teach LLMs to personalize – an approach inspired by writing education. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2308.07968.

- LLM-Rec: Personalized recommendation via prompting large language models. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2307.15780.

- A test of the international personality item pool representation of the revised NEO personality inventory and development of a 120-item IPIP-based measure of the five-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 26(4).

- Personality Traits. Cambridge University Press.

- Robert McCrae. 2010. The place of the FFM in personality psychology. Psychological Inquiry, 21(1):57–64.

- Consensual validation of personality traits across cultures. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(2):179–201.

- Mistral AI. 2023. Mistral 7B. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2310.06825.

- Open AI. 2023. GPT-4 technical report. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2303.08774v3.

- LaMP: When large language models meet personalization. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2304.11406.

- Personality traits in large language models. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2307.00184.

- Memory-augmented LLM personalization with short-and long-term memory coordination. Arxiv preprint: arXiv:2309.11696.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, to guide future research.

- Construct validity: The suitability of administering a human self-report inventory (IPIP-NEO-120) to LLMs is unvalidated; establish convergent validity with alternative measures (e.g., human rater judgments of generated texts, linguistic feature-based trait inference).

- Scoring transparency: The paper does not detail scoring procedures (e.g., reverse-coded items, domain aggregation, facet mapping); provide item-to-domain keys and scoring code to ensure replicability.

- Facet-level resolution: Results are reported only at the domain level; analyze and report facet-level scores to identify which subtraits drive observed differences across models.

- Handling of refusals/missing data: Llama2 refused two items; the method for handling missing responses (e.g., imputation, exclusion) is unspecified; document and assess the impact on domain scores.

- Normative anchoring: There is no comparison to human normative distributions; contextualize LLM scores via human percentiles and report effect sizes versus human baselines.

- Statistical inference: No hypothesis tests, confidence intervals, or standardized effect sizes are reported for differences across models, prompts, or temperatures; quantify uncertainty and significance.

- Reliability metrics: Internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha per domain/facet) and test–retest reliability across sessions/days are not assessed; establish reliability akin to psychometrics for humans.

- Factor structure: It is unknown whether the LLM item responses recover the canonical five-factor structure; conduct EFA/CFA to test dimensionality and construct fidelity.

- Social desirability and acquiescence bias: Potential RLHF-driven positivity (elevated agreeableness/conscientiousness) is not controlled; include validity/lie scales, forced-choice items, or ipsatization to assess response biases.

- Memorization/contamination: LLM familiarity with IPIP items may drive desirability-consistent answers; test with paraphrased, obfuscated, or novel items to assess robustness to item form.

- Prompting effects: Only a minimal header variation was tested; systematically map prompt space (persona cues, role instructions, context framing) and estimate effect sizes on trait scores.

- Decoding hyperparameters: Only temperature was varied; investigate top-p, top-k, repetition penalty, and random seeds to characterize decoding-induced variability in trait estimates.

- Determinism anomaly: Zero standard deviation for Llama2/Mixtral suggests deterministic decoding or ineffective temperature settings; audit inference settings and re-run with controlled randomness to assess stability.

- Context/ordering effects: The procedure for item administration (single vs multiple sessions, item order, context carryover) is unclear; randomize item order and isolate context to quantify priming/path-dependence.

- Versioning and drift: GPT-4 version/date and model updates are not controlled; evaluate temporal stability of scores across model updates and providers.

- Cross-lingual generalization: The study appears to be English-only; replicate with validated translations across languages to test measurement invariance.

- Model family breadth: Only three models were evaluated; extend to diverse architectures (e.g., Claude, PaLM/Flan, Gemini, Llama3) and sizes to assess generalizability and scaling effects.

- Base vs instruction-tuned effects: The role of RLHF/instruction tuning on trait profiles is not isolated; compare base, instruction-tuned, and safety-aligned variants to quantify alignment-induced personality shifts.

- Persona controllability: The paper does not test targeted trait induction; evaluate whether prompting or fine-tuning can reliably steer models to specified Big Five levels with calibration and stability.

- Downstream behavioral validity: It is unclear whether self-report-like scores predict actual trait expression in tasks (e.g., dialogue style, cooperation); correlate domain scores with behavior in ecologically valid scenarios.

- Human-perception validation: No human studies verify that users perceive the purported personalities; have raters blind to conditions assess generated outputs for Big Five traits and compare to inventory-based scores.

- Robustness across domains and roles: Trait profiles are not tested under different task contexts (e.g., tutor, healthcare, NPC); evaluate context sensitivity and trait stability across roles.

- Safety and ethics: The instruction “Answer as if you were a person” may circumvent safety policies; quantify refusal rates, policy interactions, and ethical implications of persona simulation in sensitive settings.

- Reproducibility artifacts: Exact prompts, seeds, decoding configs, raw item-level responses, and code are not provided; release materials to enable replication and secondary analyses.

- Measurement equivalence: Assess whether items function similarly for LLMs and humans (differential item functioning), and whether trait score interpretations are commensurate across entities.

- Adversarial and stress tests: Explore whether adversarial prompts or contradictory role cues destabilize trait scores; characterize boundaries of stability and failure modes.

- Longitudinal stability: Test whether trait estimates drift over time within the same session and across days, and whether memory/state carryover modulates responses.

Glossary

- Agency: The capacity to act intentionally and make autonomous decisions; used to clarify that LLMs do not possess intentionality. "LLMs, being statistical devices, do not exhibit agency of any kind; the concept of 'personality', as we intend to use it in this work, solely refers to the degree to which LLM output possesses properties in line with human-generated text."

- Agreeableness: A Big Five trait reflecting cooperativeness, trust, and compassion. "Mixtral also scores higher on openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness."

- Anthropomorphism: Attributing human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities like LLMs. "This type of anthropomorphism lies at the very heart of the intended uses of generative language technologies."

- Big Five model: A widely accepted personality model comprising five traits: conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion. "The FFM, also known as the Big Five model, encompasses five fundamental personality traits: conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion (See Table \ref{big5})."

- Conscientiousness: A Big Five trait associated with self-discipline, organization, and dependability. "Mixtral also scores higher on openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness."

- Cross-observer agreement: The extent to which different observers consistently assess the same traits in a subject. "Several studies have established moderate cross-observer agreement for most personality traits \cite{funder1997congruence}."

- Extraversion: A Big Five trait reflecting sociability, assertiveness, and energetic engagement with others. "GPT4 shows the highest inclination towards extraversion out of the three tested models, suggesting a suitability for tasks requiring creative and engaging language use."

- Five-Factor Model (FFM): Another name for the Big Five, a taxonomy for describing personality using five broad dimensions. "One of the most prevalent and consistently reproducible methods to quantify personality traits is the five-factors model of personality (FFM) \cite{kajonius:2019}."

- Fine-tuning: Adjusting a pre-trained model’s parameters on task- or domain-specific data to shape its behavior. "A natural question is to what extent the outputs of LLMs correspond to human personality traits and whether these 'personalities' may be influenced through prompting or fine-tuning."

- IPIP (International Personality Item Pool): A public-domain collection of personality assessment items used in psychometrics. "In our study, we employed the IPIP-NEO-120 method to assess the Big5 which is an enhanced iteration of the IPIP \cite{maples:2014}."

- IPIP-NEO-120: A 120-item questionnaire mapping IPIP items to the NEO personality framework to assess Big Five traits. "In our study, we employed the IPIP-NEO-120 method to assess the Big5 which is an enhanced iteration of the IPIP \cite{maples:2014}."

- Likert scale: A psychometric scale using ordered response options to measure agreement or frequency. "The prompts were instructing the model to use a Likert scale to indicate the extent to which various statements, for example the statement 'I believe that I am better than others', accurately depicts the respondent."

- Neuroticism: A Big Five trait associated with emotional instability, anxiety, and moodiness. "Its lower neuroticism score could be advantageous in contexts where emotionally balanced language is required."

- Openness to experience: A Big Five trait reflecting curiosity, imagination, and preference for novelty and variety. "The FFM, also known as the Big Five model, encompasses five fundamental personality traits: conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion (See Table \ref{big5})."

- Personalization: Tailoring model behavior or outputs to individual users’ preferences, traits, or contexts. "The personalization of LLMs is an emerging research area that has recently received significant attention \cite{li2023teach,lyu2023llm,zhang2023memory}, including a benchmark for training and evaluation of LLMs for personalization \cite{salemi2023lamp}."

- Prompting: Crafting instructions or context to elicit desired behaviors or outputs from a model. "A natural question is to what extent the outputs of LLMs correspond to human personality traits and whether these 'personalities' may be influenced through prompting or fine-tuning."

- Stability (of model outputs): The consistency of a model’s responses under small changes in inputs or parameters. "The repetition under different temperature settings allowed the assessment of the stability of the models, i.e. to ascertain whether they consistently produce similar responses."

- Temperature (sampling): A decoding parameter that controls randomness in generated text; higher values yield more diverse outputs. "Three treatments used the first prompt header variation for three different temperature settings ('low', 'medium', 'high'), and the other three treatments used the second prompt header with varying temperatures."

- Treatment (experimental): A specific experimental condition or setup under which measurements are taken. "Each treatment was repeated five times."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.