- The paper introduces a novel RL framework using the TQC algorithm to autonomously perform sample scraping, effectively addressing limitations of traditional lab automation.

- It leverages curriculum learning and force/torque feedback to optimize the scraping process in both simulated and real-world environments.

- Real-world validations with a Franka Emika Panda robot confirm the method's robustness and potential to enhance laboratory workflows.

Autonomous Robotic Sample Scraping via Reinforcement Learning

This paper introduces a novel approach to laboratory automation by applying model-free reinforcement learning (RL) to the task of sample scraping from vials, a crucial step in material discovery workflows. The work addresses the limitations of traditional laboratory automation, which relies on pre-defined motions and lacks the adaptability of human chemists, particularly when dealing with variations in sample morphology and environmental conditions. The core idea is to train a robot to scrape vial walls effectively using proprioceptive and force feedback, thereby automating a tedious and challenging manual task.

Methodology and Implementation

The authors formulate the scraping task as a finite-horizon discounted Markov decision process (MDP). The state space includes the Cartesian position of the end-effector and force/torque feedback, while the action space consists of Cartesian pose displacements. The reward function (Equation 1) is designed to incentivize reaching the target position at the bottom of the vial while maintaining contact with the vial wall. A key aspect of the implementation is the use of the Truncated Quantile Critic (TQC) algorithm, an off-policy actor-critic method known for its sample efficiency and ability to handle continuous action and state spaces. The TQC algorithm leverages quantile regression to predict a distribution for the value function.

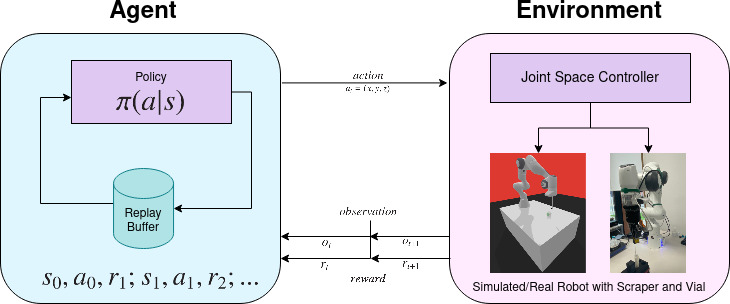

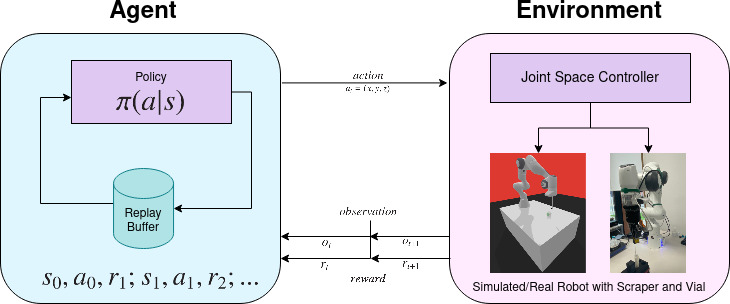

Figure 1: The overall system architecture, showcasing the RL policy and robotic controller working in tandem to achieve autonomous robotic scraping.

The model architecture is implemented using the stable baselines 3 software package, with hyperparameters optimized based on the RL baselines zoo for goal-conditioned DRL. The network consists of three hidden layers with 512 neurons each, using ReLU activation functions. The learning rate is set to 1e−3, and the replay buffer size is 10k (reduced to 500 for real robot experiments).

Simulation Experiments

The authors conduct two simulation experiments to evaluate the performance of their approach. In Experiment I, the robot learns to scrape by relying solely on proprioceptive feedback and contact force readings. The results (Figure 2) demonstrate the success rates of TQC and SAC algorithms, with TQC showing superior performance.

Figure 2: A comparison of TQC and SAC algorithms in a simulated environment, demonstrating the success rate of learning a scraping policy.

Experiment II explores curriculum learning, where the starting pose is moved outside the vial to increase the task's difficulty by requiring both insertion and scraping skills. The curriculum consists of an intermediate task where the starting state is closer to the goal. The results (Figure 3) indicate that curriculum learning significantly improves the agent's success rate and generalization ability.

Figure 3: Evaluation results comparing the success rate of learning a scraping policy with and without curriculum learning, demonstrating the benefits of curriculum learning in a more challenging environment.

Real-World Robotic Scraping Case Study

The method is further validated through a real robot experiment involving autonomous scraping of powder from a sample vial (Figure 4). The experimental setup includes a Franka Emika Panda robot equipped with a Robotiq 2F-85 gripper and force torque sensor. The robot is trained using a plastic vial and then tested on a glass vial to minimize breakage risks. The TQC model is used for the real-world experiments.

Figure 4: The physical setup of the autonomous robotic scraping system, including the robot arm, vial, and scraper, as well as a close-up of the tools used.

The scraping task involves dividing the vial into Nreg regions and repeating the scraping process within each region for a predefined duration. The robot picks up the scraping tool, moves to the scraping start pose, performs the scraping motion, places the scraper back in its holder, rotates the vial by π/12 radians, and repeats the process for all regions. Qualitative results (Figure 5) demonstrate the effectiveness of the method in removing powder from the vial walls.

Figure 5: Visual representation of the vial contents before, during, and after the robotic scraping process, demonstrating the effectiveness of the method.

Implications and Future Directions

The presented research has significant implications for laboratory automation, showcasing the potential of RL to automate complex manipulation tasks that are traditionally performed manually. The use of curriculum learning and force feedback is crucial for achieving robust and generalizable scraping policies. The successful deployment of the method on a real robotic platform demonstrates its practical applicability in chemistry workflows. The authors identify several future research directions, including the integration of visual input into the reward function and the exploration of bi-manual manipulation to enhance the scraping task's speed and efficiency.