Parameter-Robust MPPI for Safe Online Learning of Unknown Parameters

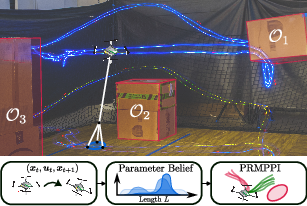

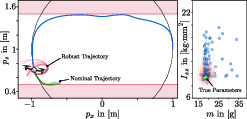

Abstract: Robots deployed in dynamic environments must remain safe even when key physical parameters are uncertain or change over time. We propose Parameter-Robust Model Predictive Path Integral (PRMPPI) control, a framework that integrates online parameter learning with probabilistic safety constraints. PRMPPI maintains a particle-based belief over parameters via Stein Variational Gradient Descent, evaluates safety constraints using Conformal Prediction, and optimizes both a nominal performance-driven and a safety-focused backup trajectory in parallel. This yields a controller that is cautious at first, improves performance as parameters are learned, and ensures safety throughout. Simulation and hardware experiments demonstrate higher success rates, lower tracking error, and more accurate parameter estimates than baselines.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching robots to stay safe while they learn about themselves. In real life, a robot doesn’t always know its exact physical details, like how heavy it is, how slippery the floor is, or how long a swinging payload might be. These details (called “parameters”) can change or be unknown at first. The authors introduce a method called Parameter-Robust MPPI (PRMPPI) that lets a robot:

- Start cautiously,

- Learn these unknown parameters while it moves,

- And keep a high chance of staying safe the whole time.

They test this on simulations and a real flying drone carrying a hanging weight.

The key questions the paper asks

The paper focuses on three big questions, written in everyday terms:

- How can a robot learn the hidden “facts about itself” (like mass or rope length) while it’s moving, without becoming unsafe?

- How can it use what it learns right away to make better, smoother moves?

- How can it guarantee a high probability of avoiding danger in the entire planned path, not just at the next step?

How the method works (explained simply)

The method combines three ideas. Think of a robot (like a drone) that needs to follow a path past obstacles while carrying a mystery-weight bag on a rope.

- Learning unknown parameters with “smart guesses” (SVGD)

- Imagine you have many different guesses of the robot’s unknown values—like many “what if the rope is this long?” scenarios. Each guess is a “particle.”

- Stein Variational Gradient Descent (SVGD) is a way to move these particles toward better guesses based on new measurements. Picture a flock of birds moving toward a food source while spreading out enough to keep exploring.

- As the robot sees what actually happens after it applies a control (for example, it speeds up and watches how the payload swings), it updates the particles to match reality better.

- Checking safety using “what-if samples” (Conformal Prediction)

- The robot wants to be, say, 90% sure it won’t hit anything over its whole planned path.

- To do this, it tries its plan under many of those parameter guesses and looks at how close each simulated path comes to danger.

- Conformal Prediction is a simple statistical tool that says: “If a certain fraction of the sampled paths stay safe, then the real path will be safe with high probability.” It turns lots of tryouts into a practical safety check.

- Choosing controls by sampling many options (MPPI), plus a backup plan

- Model Predictive Path Integral control (MPPI) works like this: try a bunch of different control sequences (tiny steering/throttle changes), simulate each one, score how good it is, then combine the best ones to decide what to do next. It repeats this every moment as the robot moves—like constantly re-planning a few seconds ahead.

- PRMPPI runs two planners in parallel:

- A “nominal” planner that tries to do the task as fast/accurately as possible, while respecting safety.

- A “robust backup” planner that focuses mainly on keeping the path safe, even if it’s less smooth or slower.

- If the nominal plan looks unsafe given the current uncertainty, the robot immediately uses the robust backup. This is like having a safe detour ready when the main route looks risky.

What the experiments found and why it matters

The authors tested their approach in both simulations and on real hardware.

- Simulations:

- Cartpole (a cart balancing a stick) and a quadrotor (a small drone) tasks with safety rules.

- PRMPPI had:

- Higher safety success rates (fewer or no safety violations),

- Lower tracking error (it followed the target path better),

- And more accurate parameter estimates (it learned the true values faster),

- compared to several baselines, including:

- A “nominal” controller that doesn’t learn,

- A “robust” controller that assumes wide uncertainty but doesn’t learn (often too conservative or unstable),

- A GP-based controller that learns a residual model but struggled when the path changed,

- And a version that used a standard Kalman filter (which didn’t capture complex, non-Gaussian uncertainty as well as PRMPPI).

- Real drone with a swinging payload:

- The drone had to fly a square path around obstacles while carrying a weight on a cable. The cable length and damping (how quickly the swinging slows down) were unknown.

- At first, the drone flew cautiously. As it learned the cable length and damping, it safely took shorter routes (like going under one obstacle and over another) without collisions.

- Using the robust backup path prevented crashes when the “best-looking” path turned out risky under some parameter guesses.

- Learning multiple parameters (length and damping) gave better accuracy and better tracking than learning length alone.

Why this matters:

- The robot doesn’t need perfect models in advance. It starts safe and gets better as it learns.

- It reduces the time and effort engineers spend hand-tuning parameters.

- It makes real-time safety practical, even when the world and the robot’s own properties are uncertain.

What this could mean going forward

PRMPPI shows a promising way to mix learning and safety:

- Robots (drones, delivery bots, factory arms) can begin working sooner, learn what they need on the job, and still keep a high chance of staying safe.

- The idea of running a “best-effort” plan alongside a “safety-first” backup could be useful in many risky tasks.

- The safety check based on sampling is simple and fast enough for real-time use.

There are still limits: safety guarantees depend on how well the “particle” guesses match reality. But because the method keeps updating as it goes, it generally stays reliable—and the results show strong performance and safety in both tests and real flights.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each item points to a concrete direction for future research.

- Formal closed-loop safety guarantees: The CP-based per-horizon test provides a pointwise probability guarantee under sampled parameters, but there is no proof of recursive feasibility or end-to-end mission safety across all timesteps. Develop formal guarantees for closed-loop operation (e.g., probabilistic invariance or cumulative risk bounds).

- CP assumptions and calibration: The guarantee hinges on i.i.d./exchangeability of parameter samples and nonconformity scores, yet the belief evolves online and is approximated via KDE. Investigate calibrated/online CP variants (e.g., split or sequential CP, robust CP) that explicitly handle belief drift and approximation error.

- Finite-sample and belief-approximation error: The paper notes potential mismatch between the particle/KDE belief and the true posterior but does not quantify its impact on safety. Derive finite-sample bounds that combine SVGD approximation error with CP quantile error; use these to adjust sample sizes and safety thresholds.

- Minimal sample size and quantile selection: The choice P = ceil((1−δ)/δ) is stated without derivation or analysis. Provide a rigorous sample-complexity justification (order-statistics or CP) and adaptive rules for choosing P to meet target coverage with finite samples.

- Parameter uncertainty only in safety probability: Safety evaluation propagates parameter uncertainty but appears to ignore process/actuation noise, disturbances, and state-estimation errors. Extend the safety probability computation to include these uncertainties (e.g., stochastic dynamics, bounded disturbances, sensor noise) and assess their impact on guarantees.

- Time-varying/abruptly changing parameters: Although motivated by parameters that may change over time, the method treats θ as static in the horizon and uses standard Bayes updates. Introduce forgetting factors, sliding-window SVGD, or change-point detection to handle nonstationary parameters and evaluate on drifting or abruptly changing systems.

- Parameter identifiability and safe excitation: Experiments reveal unobservable parameters (e.g., cartpole pendulum mass when upright). Design safe exploration inputs or dual-control strategies that actively excite informative dynamics while maintaining safety, and formalize identifiability conditions.

- Scalability to high-dimensional parameter spaces: KDE and SVGD can struggle in higher dimensions (curse of dimensionality, mode collapse). Benchmark scaling with parameter dimension, evaluate alternative belief representations (mixtures, normalizing flows, SMC), and develop adaptive bandwidth selection beyond Silverman’s rule.

- Gradient requirements and model access: SVGD updates require ∇θ f(x,u,θ) and a differentiable prior density, which may be impractical for complex or black-box dynamics. Explore gradient-free or likelihood-free variants (e.g., score estimation, simulators with automatic differentiation, or derivative-free SVGD) and quantify the effect of gradient error on learning and safety.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity and auto-tuning: Controller performance and safety depend on β (inverse temperature), penalty weight W, number of particles N, rollouts M, and kernel bandwidth σ. Provide sensitivity analysis and auto-tuning strategies (e.g., adaptive β, dynamic W, online selection of N/P/M) tied to computational budgets and safety targets.

- Computational burden and deployment constraints: Real-time performance is demonstrated with GPU acceleration on powerful hardware; feasibility on resource-constrained platforms is untested. Characterize runtime scaling laws, propose computational shortcuts (sample reuse, warm-starting, importance resampling, model reduction), and validate CPU-only deployments.

- Robust backup trajectory behavior: The backup optimization minimizes a safety robustness metric but may cause conservative or stagnant behavior near constraints. Analyze stability, progress guarantees, and deadlock avoidance; design multi-objective robust costs (safety-progress tradeoffs) with formal properties.

- Risk allocation and adaptive δ: δ is fixed per experiment; there is no mechanism for dynamic risk budgeting across time or tasks. Investigate adaptive δ schedules (e.g., risk-aware MPC, CVaR constraints) that respond to belief confidence, environment changes, or mission phases.

- Safety set modeling limitations: The approach assumes a known continuous h(x) and static constraints; partial observability is addressed heuristically with a conservative buffer. Integrate perception uncertainty rigorously (e.g., probabilistic occupancy, learned classifiers with CP), time-varying constraints, and nonconvex obstacle sets.

- Belief propagation within the planning horizon: The optimization uses a fixed posterior for the horizon; belief evolution during the horizon is ignored. Incorporate belief dynamics (e.g., dual control, POMDP approximations, belief-space MPPI) to plan actions that both achieve task goals and improve parameter estimates.

- Multi-modality and particle diversity: SVGD can under-represent multimodal posteriors with finite particles and repulsive kernels. Quantify mode coverage and compare against tempered SMC or Stein-based ensembles; develop diagnostics and corrective sampling to preserve multiple plausible parameter modes.

- Noise covariance selection and model mismatch: The observation noise covariance Σξ is set heuristically, influencing the posterior and robustness. Learn Σξ online (e.g., EM, Bayesian treatment, heavy-tailed noise models) and assess robustness to model mismatch and unmodeled effects (e.g., aerodynamics, downwash).

- Integration with residual-model learning: The method focuses on parametric uncertainty; unmodeled dynamics are treated implicitly. Combine parameter identification with residual learning (e.g., GP or neural residuals) and quantify how joint learning affects safety and performance.

- Comparative analysis with distributionally robust MPC: The paper compares to GP-MPC but not to risk measures like CVaR or Wasserstein DRO. Benchmark PRMPPI against distributionally robust formulations, analyze conservatism/performance trade-offs, and explore hybrid designs (PRMPPI with CVaR penalties).

- Broader validation scenarios: Hardware tests use a single quadrotor with suspended payload in static clutter. Validate on diverse systems (legged robots, manipulators), dynamic obstacles, tighter actuation constraints, and long-duration missions to assess robustness, learning speed, and safety at scale.

Glossary

- Adaptive domain randomization: A technique that updates the distribution of environment or model parameters online to improve robustness and performance during deployment. "Recent extensions propose adaptive domain randomization~\cite{mehta2020active, possas2020online}, where both the parameter distribution and the policy are updated online using real-world observations."

- Azimuth: The horizontal angle (around the vertical axis) describing the pendulum’s direction relative to a reference direction. "where denotes the position of the quadrotor and and denote the azimuth and polar angle of the pendulum."

- Bayes' rule: The fundamental probabilistic update rule that incorporates new evidence to refine a prior belief into a posterior distribution. "A principled way to infer these parameters is to use Bayes' rule, which updates a prior belief about the parameters using new state observations and applied control inputs "

- Certainty equivalence: A control design approach that substitutes unknown parameters with their point estimates, treating them as if they were known. "or the controller is designed for a single point estimate (e.g., maximum likelihood) of the parameters--an instance of certainty equivalence \cite{9636325}."

- Chance constrained optimal control problem: An optimal control formulation that requires constraints to be satisfied with high probability rather than deterministically. "During operation the robot observes its state and has to complete a safety-critical task which is expressed as finite horizon chance constrained optimal control problem"

- Conformal Prediction (CP): A statistical method that provides distribution-free predictive uncertainty quantification and probabilistic guarantees. "Conformal Prediction (CP) is a lightweight statistical tool for uncertainty quantification that can enable practical safety guarantees for autonomous systems \cite{shafer2008tutorial}."

- Control Barrier Functions: Lyapunov-like constructs used to enforce safety constraints in control systems by ensuring forward invariance of safe sets. "learning robust Control Barrier Functions~\cite{dawson2022learning}"

- Domain randomization: A training technique that randomizes environment or model parameters to improve transfer and robustness, especially in sim-to-real settings. "Domain randomization is a popular technique, where a controller is robustified against a predefined distribution of models ~\cite{peng2018sim}."

- Downwash force: The airflow generated by a rotorcraft’s propellers that induces forces on nearby bodies, affecting dynamics. "we found that there is a considerable effect of the generated airflow of the quadrotor (also known as downwash force) on the pendulum dynamics."

- Epistemic uncertainty: Uncertainty arising from lack of knowledge about the model or parameters, reducible with more data. "The variance of the GP prediction provides a natural quantification of epistemic uncertainty, enabling chance-constrained optimal control formulations~\cite{hewing2020learning}."

- Gaussian Process (GP) regression: A nonparametric Bayesian approach for modeling functions (e.g., residual dynamics) with uncertainty quantification via predictive variance. "In online settings, a prominent approach is to use Gaussian Process (GP) regression to model residual dynamics or unmodeled disturbances and embed this model within MPC~\cite{hewing2020learning}"

- Hamilton–Jacobi reachability analysis: A method for computing sets of states that can reach (or avoid) certain conditions, providing safety guarantees via PDEs. "HamiltonâJacobi reachability analysis~\cite{mitchell2005time}"

- Importance sampling weight: A weighting factor used in sampling-based optimization to bias samples toward lower-cost trajectories. "Then, given the state rollouts and a cost function to be minimized, each rollout is weighted by an importance sampling weight"

- Inverse temperature: A parameter in stochastic optimization or sampling that controls the sharpness or selectivity of the distribution over solutions. " is the inverse temperature which serves as a tuning parameter for the sharpness of the control distribution."

- Kernel density estimation (KDE): A nonparametric method to estimate a probability density function from samples using a smoothing kernel. "Since our belief is represented by particles which is not directly differentiable, we perform a kernel density estimation (KDE)"

- KL divergence: A measure of dissimilarity between probability distributions, often minimized in variational inference. "to reduce the KL divergence \cite{liu2016stein}."

- Lagrange’s method: A variational mechanics technique for deriving equations of motion using energy functions and generalized coordinates. "We obtain the simplified equations of motion via Lagrangeâs method"

- Likelihood-free updates: Inference procedures that update parameter beliefs without explicit likelihood functions, often using simulations. "with modern variants leveraging differentiable simulators~\cite{heiden2022probabilistic} or black-box simulation for likelihood-free updates \cite{barcelos2020disco}."

- Mass moment of inertia: A metric of rotational inertia around an axis, affecting rotational dynamics. "We uniformly randomize the quadrotor's mass and its mass moment of inertia in a range of around the nominal values of $m=27\si{g}$ and $I_z = 1.4 \cdot 10^{-5} \si{kg \cdot m^2}$."

- Mean field limit: The asymptotic regime where the number of particles goes to infinity and the empirical distribution converges to the target. "it is shown in \cite{shi2023finite} that the transported distribution converges to the true target in the mean field limit, i.e. as ."

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A control strategy that optimizes control actions over a moving finite horizon and applies the first action, repeating at each step. "Model Predictive Control (MPC) offers a way to couple learning with decision-making by updating models within a receding horizon."

- Model Predictive Path Integral (MPPI): A sampling-based optimal control method that computes control actions via weighted averages of noisy rollouts. "MPPI is a control method to solve stochastic Optimal Control Problems (OCPs) for discrete-time dynamical systems"

- Non-conformity score: A scalar measure used in conformal prediction to quantify how atypical a sample is relative to previous data or constraints. "The variable is usually referred to as the non-conformity score."

- Parameter-Robust Model Predictive Path Integral (PRMPPI): A control framework that integrates MPPI with online parameter learning and probabilistic safety constraints. "We propose Parameter-Robust Model Predictive Path Integral~(PRMPPI) control, a framework that integrates online parameter learning with probabilistic safety constraints."

- Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel: A commonly used positive-definite kernel that measures similarity based on distance, often Gaussian-shaped. "In practice, we use a radial basis function (RBF) kernel for "

- Receding horizon: The moving time window over which optimization or prediction is performed, advanced forward at each step. "Given the current state and a control input trajectory over a receding horizon "

- Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS): A Hilbert space of functions associated with a kernel, enabling functional optimization via kernel methods. "Here, is a Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS) induced by a kernel function ."

- Robust MPC: A model predictive control approach that accounts for worst-case uncertainties within bounded sets to ensure constraint satisfaction. "robust MPC~\cite{mayne2005robust}"

- Sequential Importance Resampling (SIR): A particle filtering technique that updates particle weights by likelihood and resamples to mitigate degeneracy. "Sequential Importance Resampling (SIR) filters tend to suffer from weight degeneracy"

- Silverman's rule of thumb: A heuristic for selecting the bandwidth in kernel density estimation. "we use a radial basis function (RBF) kernel for and select its bandwidth using Silverman's rule of thumb~\cite{silverman2018density}"

- Stein Variational Gradient Descent (SVGD): A particle-based variational inference algorithm that transports particles via functional gradients to approximate a target distribution. "Stein Variational Gradient Descent (SVGD) is a particle-based variational inference method"

- Taylor expansion: A linearization technique using series expansion to approximate nonlinear functions, often for uncertainty propagation. "To make such formulations tractable, different approximations for uncertainty propagation have been proposed: linearization via Taylor expansion"

- Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF): A nonlinear state/parameter estimator that propagates sigma points through dynamics to approximate means and covariances. "we add a baseline in which the parameter belief is obtained by an unscented Kalman Filter (UKF)."

- Unscented transform: A deterministic sampling technique that selects sigma points to capture mean and covariance under nonlinear transformations. "or the unscented transform~\cite{ostafew2016robust}."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following use cases can be deployed now with modest integration effort, leveraging the paper’s PRMPPI controller (SVGD-based online parameter learning + conformal-prediction safety + parallel nominal/backup MPPI):

- Robotics (UAVs/delivery drones)

- Use case: Safe payload-aware flight for consumer and enterprise UAVs with varying payloads (e.g., camera gimbals, packages) and changing aerodynamics.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- PX4/ArduPilot plugin implementing PRMPPI (SVGD parameter-estimator, CP-based trajectory safety check, robust backup trajectory).

- ROS2 node for UAVs integrating with onboard state estimation, Lighthouse/Vicon, or GPS/visual-inertial odometry.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Accurate-but-lightweight dynamics model; reliable state estimation; onboard compute (CPU/GPU) to run 30–50 Hz sampling-based control; definable safety set h(x); chance-constraint acceptable for ops.

- Robotics (AMRs/AGVs in logistics and manufacturing)

- Use case: Safe tracking and collision avoidance for ground robots carrying loads of varying mass, center of mass, and friction on changing floors (polished concrete, ramps).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- PRMPPI-enabled path follower for AMRs (integrated with fleet managers), adding a “Parameter Belief Monitor” and “Conformal Safety Auditor” to logs for auditability.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Mildly nonlinear models; fast perception for obstacle layouts; known control limits; compute budgets for rollouts; acceptance of probabilistic safety guarantees.

- Industrial manipulation (tool/end-effector changes)

- Use case: Adaptive, safe motion planning when robot arms change tools or grasp objects with unknown mass/inertia, ensuring collision-free motions near humans or fixtures.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- PRMPPI controller plugin for MoveIt/ROS2 Control; workflow for “online parameter identification during first moves,” with robust fallback trajectory for safe motion.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Rigid-body model sufficient near operating regimes; real-time joint state feedback; well-defined safety regions; certification processes may require additional assurance cases.

- Field robots (agriculture, construction, inspection)

- Use case: Safe navigation across variable terrains and loads (e.g., sprayer tank mass changes, soil friction variation, tool attachments) while respecting geofences and obstacle constraints.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- PRMPPI-based navigation stack with terrain-dependent parameter belief and CP-based safety checks; offline replay tools to evaluate coverage of non-conformity scores.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Terrain model or residual structure captured by dynamics; consistent state estimation in outdoor conditions; reliable obstacle maps.

- Academic research and teaching (safe online learning/control)

- Use case: Benchmarking safe adaptive control algorithms in courses and labs; replicating results in simulation (safe-control-gym) and on hobby-class drones (Crazyflie).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- JAX-based PRMPPI reference implementation; tutorials for SVGD-based parameter learning and CP-based horizon-wide chance constraints; curriculum modules on safe adaptive MPC/MPPI.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to GPU for large rollouts; familiarity with kernel density estimation and parameter priors; reproducible simulation environments.

- Software/Simulation tooling

- Use case: Risk-aware trajectory optimizer library for developers of robotics stacks or digital twins.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “PRMPPI-SDK” (JAX/Python) with: SVGD belief, KDE sampler, CP robustness scoring, parallel nominal/backup MPPI, ROS2 bindings; Gazebo/Isaac Sim integrations.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Developer capacity to integrate sampling-based controllers; benchmarking vs. existing MPC/MPPI stacks.

- Safety monitoring and auditing

- Use case: Operational risk dashboards that log non-conformity scores, sampled robustness, and fallback activations to support safety cases and incident analysis.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “Conformal Safety Auditor” log pipeline that stores per-trajectory robustness thresholds and parameter-belief snapshots for audit/regulatory discussions.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Organizational acceptance of probabilistic guarantees; data retention/compliance processes.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, or regulatory acceptance (e.g., stronger guarantees, richer models, higher-dimensional parameters, formal verification):

- Autonomous driving (automotive)

- Use case: Adaptive, safe trajectory planning under uncertain tire-road friction, payload distribution, or trailer dynamics, with chance-constrained safety envelopes in urban driving.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Integration of PRMPPI with motion planning stacks; expanded CP variants for non-i.i.d. and distribution shift; formal runtime monitors for ISO 26262 safety cases.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Certification-grade models and datasets; tight real-time inference; robustness to rare events; assurance beyond empirical CP; high-fidelity perception.

- Medical and rehabilitation robotics (healthcare)

- Use case: Patient-specific parameter adaptation (tissue stiffness, limb dynamics) with probabilistic safety during physical human-robot interaction (surgery, exoskeletons).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- PRMPPI-based controllers with richer biomechanical models and h(x) that encode safety envelopes for force/position; clinical-grade logging for regulatory audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Regulatory approval; stronger guarantees than approximate CP; validated patient models; fault-tolerant hardware.

- Human-robot collaboration (cobots)

- Use case: Real-time adaptation to tool changes and co-manipulated objects while maintaining human-centric safety margins and varying interaction dynamics.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Integration with learned human motion predictors; robust trajectory fallbacks when people approach; policy for parameter resets during tool swaps.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable human detection and prediction; standards compliance (ISO 10218, ISO/TS 15066); explainable safety metrics.

- Large-scale aerial logistics and inspection

- Use case: Swarms of drones with variable payloads, wind fields, and battery states, coordinating safely around infrastructure with probabilistic guarantees.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Multi-robot PRMPPI with shared parameter beliefs, distributed CP-based safety for inter-robot constraints; fleet-level safety telemetry.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Distributed compute/communication; scalable belief fusion; airspace regulatory acceptance of adaptive controllers.

- Energy systems and renewables

- Use case: Adaptive pitch/torque control in wind turbines or airborne wind systems with changing aerodynamic parameters (icing, wear) under safe operating envelopes.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reduced-order models augmented with PRMPPI; CP-based safety margins for gusts and parameter shifts; integration with SCADA.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- High-confidence models of aeroelastic dynamics; long-horizon predictions beyond current receding horizons; industrial certification.

- Legged robots and high-dof manipulators

- Use case: Safe locomotion/manipulation with rapidly changing contact/friction parameters and complex, high-dimensional models.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Hybrid model approaches (rigid-body + learned residuals) inside PRMPPI; more expressive kernels for SVGD; hardware acceleration for massive rollouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Efficient contact modeling; high-rate sensing (force/torque); compute budgets or dedicated accelerators.

- Policy and standards

- Use case: Frameworks recognizing probabilistic safety for adaptive controllers (e.g., chance-constrained guarantees with conformal calibration) in certification processes.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Standardized reporting of robustness scores and calibration procedures; “robust CP” extensions and finite-particle bounds for assurance cases.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Consensus on acceptable risk levels; alignment with sector-specific standards; reproducible calibration datasets.

- Consumer robotics and daily-life devices

- Use case: Home robots (vacuum/mopping, eldercare assistants) adapting to variable loads and surfaces while maintaining safe trajectories around people and objects.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Lightweight PRMPPI variants running on embedded SoCs; user-adjustable safety profiles; self-calibration workflows during first-use.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Low-cost sensors and compute; robust perception; transparent user controls and fail-safes.

Notes on Feasibility and Dependencies

- Model availability and fidelity: PRMPPI presumes a known, differentiable dynamics model with a small set of uncertain parameters; large unmodeled effects (e.g., strong aerodynamics) may require residual modeling or additional parameters.

- State estimation and sensing: Reliable state feedback is critical; performance in the paper relied on Lighthouse/Vicon for drones—real deployments need onboard VIO/LiDAR/GPS with known noise characteristics.

- Computational budget: Achieved 30–50 Hz with GPU acceleration and up to 105 rollouts; embedded deployment may need pruning, warm starts, or specialized accelerators.

- Safety guarantees are probabilistic and belief-dependent: Conformal Prediction provides coverage w.r.t. the belief over parameters; approximation via finite particles/KDE and the i.i.d. assumption can lead to conservatism or rare violations.

- Safety function design: Defining h(x) that captures relevant hazards (collisions, joint limits, geofences) is a prerequisite; conservative shaping increases success rates but may reduce performance.

- Tuning and calibration: Kernel bandwidths (KDE), observation noise covariance, inverse temperature in MPPI, and sample counts (P) impact both safety and performance; domain-specific calibration workflows are needed.

- Parallel robust trajectory: The backup trajectory mitigates divergence when nominal samples become unsafe; requires a well-defined robust objective and careful switching logic for smooth control.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.