What Drives Success in Physical Planning with Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models?

Abstract: A long-standing challenge in AI is to develop agents capable of solving a wide range of physical tasks and generalizing to new, unseen tasks and environments. A popular recent approach involves training a world model from state-action trajectories and subsequently use it with a planning algorithm to solve new tasks. Planning is commonly performed in the input space, but a recent family of methods has introduced planning algorithms that optimize in the learned representation space of the world model, with the promise that abstracting irrelevant details yields more efficient planning. In this work, we characterize models from this family as JEPA-WMs and investigate the technical choices that make algorithms from this class work. We propose a comprehensive study of several key components with the objective of finding the optimal approach within the family. We conducted experiments using both simulated environments and real-world robotic data, and studied how the model architecture, the training objective, and the planning algorithm affect planning success. We combine our findings to propose a model that outperforms two established baselines, DINO-WM and V-JEPA-2-AC, in both navigation and manipulation tasks. Code, data and checkpoints are available at https://github.com/facebookresearch/jepa-wms.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper studies how to make robots plan actions better by using a learned “world model” that can imagine the future. Instead of planning directly with raw images, the robot plans in a smarter, compressed space of features learned from images. The authors ask: which design choices actually make this kind of planner work best? They test many options and combine the best ones to beat strong existing methods on both simulated tasks and real robot data.

What questions did the researchers ask?

In simple terms, they wanted to know:

- How should we train a robot’s “imagination” so it predicts the future well enough to plan actions?

- Which parts of the system matter most: the type of visual features, the robot’s body sensors, the size of the model, how far ahead it imagines, or the planning algorithm itself?

- What combination of these choices leads to the most reliable success when the robot must move around or manipulate objects?

How did they study it?

What is a “world model”?

Think of a world model like a robot’s imagination. It sees recent frames from a camera and the robot’s own moves, and then predicts what the next step will look like. It works in a compact “feature space” (a kind of secret code or summary of the image) rather than raw pixels. This is called planning in the model’s “latent space.”

- Encoder: turns each image (and optionally the robot’s body readings) into features.

- Predictor: given recent features and the planned actions, predicts the next features.

- Planner: searches for a sequence of actions that make the predicted future look like the goal.

How does planning work?

- Start with an initial observation and a goal image.

- Try many candidate action sequences (like paths in a maze).

- Use the world model to “imagine” the results of each candidate.

- Score each result by how close it is to the goal in feature space.

- Keep improving the candidates until you find a good plan.

Two families of planners are used:

- Sampling-based planners (like CEM): try a bunch of action sequences, keep the best, and focus more around them next time.

- Gradient-based planners (like GD/Adam): tweak the actions directly using derivatives to reduce the distance to the goal.

What design choices did they test?

They systematically varied and tested, one at a time:

- Planning algorithm: CEM, Nevergrad (a family of smart optimizers), gradient descent, Adam.

- Multistep training: whether the predictor “practices” imagining several steps ahead during training, not just the next step.

- Proprioception: whether to include the robot’s body sense (joint angles, gripper state) alongside vision.

- Context length: how many past frames the predictor can see to understand motion (velocity).

- Visual encoder type: image feature extractors like DINOv2/DINOv3 vs video encoders like V-JEPA; all were frozen (not retrained).

- Predictor architecture: different ways to feed actions into the predictor (feature conditioning, sequence conditioning, or AdaLN) and different positional encodings.

- Model size: small vs big encoders and shallow vs deep predictors.

- Datasets: both simulated tasks (moving to a target, navigating mazes) and real robot videos (manipulating objects), including a zero-shot transfer test to a new environment.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main takeaways:

- Planning algorithm:

- CEM with L2 distance was the most reliable overall across tasks.

- Nevergrad performed similarly to CEM on real robot data and needed less tuning, which is handy when trying new tasks.

- Gradient-based methods (GD/Adam) worked well on smooth, easy tasks (like simple reaching) but struggled on harder navigation and manipulation tasks with traps and local minima.

- Multistep training helps—but don’t overdo it:

- Training the predictor to imagine a few steps ahead (about 2 steps for simulations, up to ~6 for real robot data) improved planning success.

- Training for too many steps could hurt, likely because it spreads learning too thin over longer horizons than needed.

- Proprioception helps:

- Including the robot’s body readings made planning more precise, especially for reaching tasks where tiny position errors matter.

- Context length matters (but not too long):

- Seeing at least 2 past frames (to infer velocity) gave a big boost over seeing just 1.

- Longer context than needed can slow learning without helping much, except on complex real-world data where a bit longer (like 5) helped.

- Better image features beat video features for these tasks:

- DINO-style image encoders (great at precise object localization) outperformed video encoders (V-JEPA) for planning.

- DINOv3 did especially well on photorealistic, real-world data.

- Predictor design:

- A conditioning method called AdaLN was a strong, consistent choice for feeding action information into the predictor, though the best option can vary by task.

- The choice of positional encoding (technical way to track “where/when” tokens are) mattered less than the action-conditioning method.

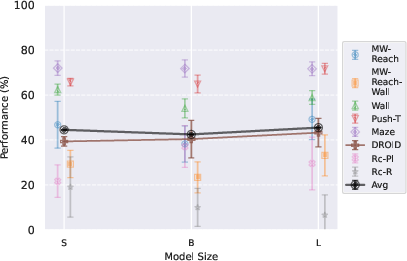

- Model size:

- Bigger isn’t always better in simulation—small and mid-sized models did fine and sometimes better.

- Larger models helped on real robot data (more complex and varied).

- Overall result:

- Combining the best choices, the authors built a model that beats two strong baselines (DINO-WM and V-JEPA-2-AC) on navigation and manipulation tasks, including real-world videos.

So what’s the impact?

This work gives practical guidelines for building robot planners that imagine in a compact feature space:

- Use strong image features (like DINO), short-but-sufficient context (2–3, more for real data), a bit of multistep training, and include proprioception when available.

- Prefer CEM for general reliability, or Nevergrad to avoid hyperparameter fiddling. Use gradient-based planning only on very smooth, easy tasks.

- Scale model size mainly for real-world complexity, not for simple simulations.

- With these choices, robots can plan better from raw video and transfer more reliably to new settings.

In short, the paper turns a lot of tricky design decisions into a practical recipe, helping future robot systems plan faster and more successfully—without needing hand-crafted rewards or massive fine-tuning for each new task.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete gaps and open questions that remain unresolved, focusing on what is missing, uncertain, or left unexplored in the paper. Each item is formulated to be actionable for future research.

- Planning objective alignment:

- The planning cost is a simple latent-space distance to the goal at the final step; it is unclear whether this metric reliably captures task success across environments. Investigate learned goal scorers, contrastive distances, potential-based shaping, or geodesic distances aligned with controllability and temporal reachability.

- The paper mentions could aggregate intermediate rollouts but uses only the terminal embedding; study path-aware costs (e.g., waypoint penalties, barrier terms, collision avoidance) and their effect on long-horizon, non-greedy tasks.

- World model uncertainty and robustness:

- The predictor is deterministic and does not quantify epistemic/aleatoric uncertainty; examine ensembles, stochastic predictors, or Bayesian approaches and risk-sensitive planning to handle multi-modal dynamics and real-world noise.

- Robustness to observation noise, occlusions, lighting changes, and actuation noise is not evaluated; systematically measure sensitivity and develop noise-aware training/planning.

- Training regime and rollout learning:

- Multistep rollout training uses TBPTT with gradients only on the last prediction; compare against full backprop through time, scheduled sampling, DAgger-like data aggregation, or curriculum rollout lengths to mitigate compounding error.

- The optimal number of rollout steps is environment-dependent (e.g., 2 in simulation vs 6 in DROID) but the cause is not analyzed; characterize how dynamics complexity and dataset properties govern optimal rollout training.

- Frameskip and action concatenation (f×A) during training are mentioned but not systematically studied; quantify how frameskip choices affect stability, long-horizon accuracy, and planner performance.

- Context length and memory:

- Planning uses a fixed context ; the trade-off between longer test-time context and computational cost is not explored. Assess adaptive context selection (e.g., memory gating, learned context windows) and recurrent/state-space models for better long-range dependence.

- Increasing training context reduces the number of unique slices seen per epoch; disentangle data-efficiency vs. context benefits via controlled scaling of dataset size and gradient steps, and study sampling strategies that maintain diversity at higher .

- Representation choice and alignment:

- Frozen encoders (DINOv2/v3, V-JEPA) are used without finetuning; evaluate end-to-end training of encoder+predictor and its impact on planning, as well as representation adaptation for task-specific metrics.

- Larger embedding spaces can hamper planning due to poor local discriminability; develop “planning-friendly” representation learning (e.g., metric learning for temporal distances, controllability-aware embeddings, manifold regularization).

- The superiority of DINO versus V-JEPA is attributed to fine-grained segmentation, but this is not quantified; benchmark dense perception quality (e.g., segmentation, keypoints) and correlate with planning success.

- Action conditioning and architectural choices:

- AdaLN conditioning performs best on average but the reasons (e.g., action signal preservation across layers) are hypothesized rather than measured; probe internal activations, information flow, and gradient norms to validate the mechanism.

- Action-to-visual embedding ratio effects are confounded across conditioning schemes; extend equalized-ratio experiments across tasks to conclusively isolate architectural benefits.

- Positional embeddings (sincos vs RoPE) show limited improvements; analyze inductive biases for temporal dynamics (e.g., relative positional encodings, learned time embeddings) and their impact on extrapolation.

- Planner design and optimization landscape:

- The study fixes CEM as default but does not explore more expressive population-based methods (full-covariance CMA-ES, MAP-Elites, cross-entropy variants with constraints) or hybrid planners (sampling+gradient refinement).

- NGOpt is used as a black-box without tuning; systematically compare NG families (e.g., PSO, DE, CMA variants), budgets, and restart strategies, and characterize when NG’s exploratory behavior is beneficial or detrimental.

- Gradient-based planners fail on multi-modal landscapes; investigate continuation methods, trajectory smoothing, differentiable constraints, trust-region updates, or leveraging learned value functions to guide optimization.

- Planner hyperparameters (horizon H, replanning frequency m, population size N, iterations J) are fixed per environment; conduct sensitivity analyses and propose auto-tuning strategies that generalize across tasks.

- Hierarchical and long-horizon planning:

- No hierarchical decomposition (subgoals, options, skill libraries) is used; evaluate learned subgoal generators or hierarchical policies to improve non-greedy, long-horizon tasks (e.g., mazes, contact-rich manipulation).

- Integrate goal-conditioned RL/value learning with JEPA-WMs for better credit assignment and planning guidance, especially on sparse-reward tasks.

- Proprioception and embodiment:

- Proprioception significantly helps in simulation but is disabled for cross-dataset transfer (DROID→Robocasa) due to misaligned spaces; develop embodiment-agnostic proprioceptive representations or alignment methods to enable zero-shot transfer with proprioception.

- The weighting α between visual and proprioceptive distance is hand-set (0 vs 0.1); investigate adaptive or learned multi-objective weighting schemes, and study sensitivity.

- Data and evaluation coverage:

- Real robot execution is not performed; validate on physical hardware with closed-loop MPC, safety constraints, and latency, and measure sim-to-real performance gaps.

- Success rate exhibits high variance; propose more stable metrics or evaluation procedures (e.g., bootstrapping across seeds, calibrated confidence intervals) and analyze sources of variance (training noise, planner randomness).

- Dataset scale, diversity, and quality vs performance are not quantified; run controlled data scaling studies (size, heterogeneity, demonstrations quality) and derive empirical scaling laws for JEPA-WMs.

- Safety and constraints:

- Planning ignores physical constraints (collisions, torque limits, workspace boundaries); incorporate constraint-aware planning (e.g., penalty terms, differentiable physics proxies, safety filters) and evaluate trade-offs with success.

- Generalization and transfer:

- Generalization beyond the studied tasks/environments (e.g., dynamic obstacles, deformable objects, multi-agent settings) is untested; build benchmarks that stress compositional generalization and out-of-distribution robustness.

- Cross-domain transfer is limited (e.g., DROID→Robocasa without proprioception); explore domain adaptation (feature alignment, adversarial training, synthetic-to-real bridging) and task-conditioned fine-tuning.

- Goal specification:

- Goals are frames or states sampled from datasets or expert policies; extend to language-specified goals, spatial sketches, or task constraints, and study multi-modal goal grounding in representation space.

- Computational efficiency:

- Compute/training cost vs performance is not analyzed; report wall-clock, GPU-hours, memory footprint, and planner runtime, and evaluate cost-effective training (e.g., distillation, low-rank adapters, caching).

- Predictive fidelity vs planning success:

- The paper notes good rollouts do not guarantee planning success, but the causal factors remain unclear; analyze failure modes (representation misalignment, local minima, compounding prediction errors) and design diagnostics linking world-model quality metrics to downstream success.

Glossary

- AdaLN (Adaptive LayerNorm): A conditioning mechanism that modulates transformer layers using external signals (e.g., actions) to inject conditioning information throughout the network. "Another efficient conditioning technique is AdaLN~\citep{AdaLN}, as adopted by \citet{NWM_Bar_2025_CVPR}, which we also put to the test, using RoPE in this case."

- AMI (Autonomous Machine Intelligence): A framework emphasizing MPC-based planning as central to autonomous intelligence. "âA path towards machine intelligenceâ \citep{PathAMI} presents planning with Model Predictive Control (MPC) as the core component of Autonomous Machine Intelligence (AMI)."

- CEM (Cross-Entropy-Method): A population-based trajectory optimizer that iteratively updates a sampling distribution toward lower-cost solutions. "\citet{DINO-WM, TDMPC2, PLDM, VJEPA2, NWM_Bar_2025_CVPR} use the Cross-Entropy-Method (CEM) (or a variant called MPPI~\citep{MPPI})."

- CMA-ES (Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy): An evolutionary strategy that adapts the covariance of a Gaussian search distribution to efficiently explore continuous spaces; CEM is a simpler variant. "CEM is a variant of the CMA-ES family~\citep{CMA1996, hansen2023cmaevolutionstrategytutorial} with diagonal covariance and simplified update rules."

- Diffusion-based planners: Planners that generate action trajectories by iterative denoising from noise, enabling multi-modal and constraint-aware planning. "and diffusion-based planners~\citep{Diffuser, DMPC}."

- DINOv2: A self-supervised vision transformer producing strong local features used as fixed encoders for planning and prediction. "a JEPA model trained on a frozen DINOv2 encoder outperforms DreamerV3~\citep{DreamerV3} and TD-MPC2~\citep{TDMPC2}"

- DINOv3: A successor to DINOv2 with improved dense prediction capabilities, beneficial in photorealistic manipulation and navigation. "we use the local features of DINOv2 and the recently proposed DINOv3~\citep{simeoni2025dinov3}, even stronger on dense tasks."

- DreamerV3: A model-based RL algorithm that learns world models and policies from pixels with high sample efficiency. "DINO-WM~\citep{DINO-WM} shows that ... a JEPA model trained on a frozen DINOv2 encoder outperforms DreamerV3~\citep{DreamerV3}"

- E2C (Embed to Control): A locally linear latent dynamics model enabling trajectory optimization with iLQR in a learned latent space. "Locally-linear latent dynamics models, such as Embed to Control (E2C)~\citep{E2C}, learn a latent space where dynamics are locally linear, enabling the use of iterative Linear Quadratic Regulator (iLQR) for trajectory optimization."

- Feature conditioning: Conditioning strategy where action/proprioceptive embeddings are concatenated to visual features along the embedding dimension. "their output is concatenated to the visual encoder output along the embedding dimension, which is known as feature conditioning~\citep{IWM}"

- Flow matching: A generative modeling technique that learns to transport probability mass, used here to generate action trajectories. "Physical Intelligence's first model ~\citep{pi0} uses the Open-X embodiment dataset and flow matching to generate action trajectories."

- GCRL (Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning): RL that conditions policies on goals to learn goal-reaching behavior from reward-free data. "Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning (GCRL) offers a self-supervised approach to leverage large-scale pretraining on unlabeled (reward-free) data."

- iLQR (iterative Linear Quadratic Regulator): A trajectory optimization method for locally linear dynamics and quadratic costs used in latent control. "enabling the use of iterative Linear Quadratic Regulator (iLQR) for trajectory optimization."

- JEPA (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures): Representation learning architectures where one view predicts another in a shared embedding space. "the Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures (JEPAs) proposed by \citet{PathAMI}, where a representation of some data is constructed by learning an encoder/predictor pair such that the embedding of one view of some data sample predicts well the embedding of a second view."

- JEPA-WMs (Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models): World models that learn predictive dynamics in the representation space of a JEPA encoder and plan directly in that space. "We will focus on {\em action-conditioned Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models} (or {\em JEPA-WMs}) learned from videos~\citep{PLDM, DINO-WM, VJEPA2}."

- LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity): A perceptual metric evaluating visual similarity between images in feature space. "visual decoding of open-loop rollouts (and the LPIPS between these decodings and the groundtruth future frames)."

- MPC (Model Predictive Control): A control strategy that repeatedly solves a finite-horizon optimization and replans as new observations arrive. "presents planning with Model Predictive Control (MPC) as the core component of Autonomous Machine Intelligence (AMI)."

- MPPI (Model Predictive Path Integral): A sampling-based control method closely related to CEM for trajectory optimization. "(or a variant called MPPI~\citep{MPPI})"

- NeverGrad: A library of gradient-free optimizers used to perform trajectory optimization without tuning custom parameters. "we introduce a planner that can make use of any of the optimization methods from NeverGrad~\citep{NeverGrad}."

- NGOpt: A meta-optimizer in Nevergrad that selects and configures algorithms based on problem parametrization and budget. "we choose the default NGOpt optimizer~\citep{anonymous2024ngiohtuned}, which is designated as a âmetaâ-optimizer."

- Proprioception: Internal robotic sensing (e.g., joint angles, velocities) used alongside vision to represent state and guide planning. "Models trained with proprioceptive input are denoted

prop", while pure visual world models are namedno-prop"." - Q-function: A function estimating the expected return of state-action pairs, used in RL for policy improvement. "model-based RL uses a given or learned model of the environment in the training of its policy or Q-function~\citep{AlphaZero}."

- Registers (DINOv2 registers): Special learned tokens injected into ViT architectures to enhance representation quality. "using DINOv2 ViT-B and ViT-L with registers~\citep{registers}."

- RoPE (Rotary Position Embeddings): A positional encoding technique that rotates queries/keys to inject relative position information into attention. "Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) is used at each block of the predictor."

- Sequence conditioning: Conditioning strategy where actions/proprioception are encoded as tokens and concatenated to visual tokens along the sequence dimension. "as opposed to sequence conditioning, where the action and proprioception are encoded as tokens, concatenated to the visual tokens sequence, which is adopted in V-JEPA-2~\citep{VJEPA2}."

- Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): Learning from data without explicit labels by using proxy objectives. "World Models learned via Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)~\citep{fung2025embodiedaiagentsmodeling} have been used in many reinforcement learning works"

- Sincos positional embeddings: Sinusoidal/cosine deterministic positional encodings used to inject spatial-temporal position information. "The main difference ... is that the first uses feature conditioning, with sincos positional embedding, whereas the latter performs sequence conditioning with RoPE"

- TBPTT (Truncated Backpropagation Through Time): Training technique that limits gradient propagation across long sequence unrolls to reduce compute and instability. "In practice, we perform truncated backpropagation over time (TBPTT)~\citep{ELMAN1990179, TBPTT2002tuto}"

- ViT (Vision Transformer): A transformer-based architecture for images that processes tokenized patches with self-attention. "The architecture chosen for the encoder and predictor in this study is ViT~\citep{VITs}"

- V-JEPA: A video JEPA encoder that produces representations from short video clips rather than single images. "We train a predictor on top of video encoders, namely V-JEPA~\citep{VJEPA} and V-JEPA-2~\citep{VJEPA2}."

- V-JEPA-2-AC: A video JEPA variant with action conditioning that enables planning for object manipulation via image subgoals. "The V-JEPA-2-AC~\citep{VJEPA2} model is able to beat Vision Language Action (VLA) baselines like Octo~\citep{octo_2023} in greedy planning for object manipulation using image subgoals."

- VLA (Vision Language Action): Multimodal models that map visual and language inputs to actions in robotics tasks. "Vision Language Action (VLA) baselines like Octo~\citep{octo_2023}"

- VQ-VAE objective: A discrete latent variable autoencoding objective used to learn quantized action representations. "learning discrete latent actions using the VQ-VAE objective on robot videos."

- Visual servoing: A control approach that uses visual feedback to drive a robot to desired states. "akin to the long-standing visual servoing problem~\citep{VisualServoControl}."

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper analyzes and optimizes Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models (JEPA-WMs) for physical planning. It identifies which components—visual encoders (DINOv2/v3 vs. V-JEPA), predictor architectures (feature/sequence conditioning vs. AdaLN, sincos vs. RoPE), training choices (multistep rollout, context length W, proprioception), and planning optimizers (CEM, Nevergrad NGOpt, gradient-based)—most strongly influence success across navigation and manipulation tasks. The authors provide open-source code, data, checkpoints, and propose configurations that outperform established baselines (DINO-WM, V-JEPA-2-AC) in both simulated and real robotic settings.

Below are practical, real-world applications derived from these findings, organized by deployment horizon. Each bullet highlights sector relevance, potential tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be built or piloted with the released code, pretrained encoders, and recommended planner/training recipes.

- World-model-based planning modules for industrial and research robotics

- Sectors: robotics (manufacturing, logistics), research labs

- What to deploy now:

- Integrate a JEPA-WM planning module using a pretrained DINO encoder, a transformer predictor with AdaLN conditioning, and CEM with L2 distance for planning.

- Use the recommended context lengths: W=3 and predictor depth≈6 for simulated tasks; W=5 and depth≈12 for photorealistic/real tasks (DROID-like).

- Include proprioception when sensor spaces align (improves precision near goals) and set planning context Wp=2.

- Tools/workflows: ROS-compatible planner wrapper; latent-space MPC using image goals; “AutoPlanner” heuristic to select optimizer (CEM for complex/multi-modal, NGOpt for quick deployment across domains, Adam/GD for smooth tasks like simple reaching).

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to robot telemetry (state-action trajectories), calibrated cameras; encoder choice aligned to visual domain (DINOv3 for photorealistic); goal-image definition available; safety constraints and low-latency control loop in place.

- Goal-conditioned manipulation without reward engineering (offline trajectories)

- Sectors: warehouse automation, e-commerce fulfillment, lab automation

- What to deploy now:

- Use JEPA-WM to plan pick-and-place or reaching from offline teleoperation datasets; define goals by images rather than hand-crafted rewards.

- Tools/workflows: dataset ingestion pipeline; subgoal selection by latent closeness; CEM L2 for non-greedy plans; multistep rollout training (2-step for simulated, up to 6-step for real data to stabilize longer rollouts).

- Assumptions/dependencies: coverage of trajectories near target behaviors; accurate goal-frame selection; sufficient compute for sampling-based planning within control cycle.

- Real-robot prototyping in labs using NGOpt planner for rapid iteration

- Sectors: academia, startups, R&D

- What to deploy now:

- Use Nevergrad NGOpt as a hyperparameter-light planner to boot new tasks quickly (especially when CEM tuning is costly); swap to CEM once scaling and budgets are known.

- Tools/workflows: NGOpt planner interface from the repo; fast task bring-up via default NG settings; later switch to tuned CEM for performance-critical deployments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: compute budget adequate for sampling; reliance on embedding L2 cost as proxy for task success; planner horizon and batch sizes set per environment.

- Latent visual servoing in embedded systems

- Sectors: robotics (assembly cells, lab instrumentation), education

- What to deploy now:

- Replace pixel-space servoing with latent-space objectives using DINO features and JEPA predictor; track latent L2 to a target image state with MPC-like re-planning.

- Tools/workflows: latent target generation; periodic re-planning; predictor unrolling with Wp=2 for state evolution; AdaLN conditioning to preserve action signal across layers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable camera configurations; encoder features cover relevant spatial detail; latency/compute constraints support real-time sampling.

- Benchmarking and curriculum design for world-models

- Sectors: academia, education

- What to deploy now:

- Use the unified codebase to teach/benchmark choices (encoders, conditioning, planner types, context length, rollout training) with zero/reward-free datasets.

- Tools/workflows: reproducible ablations; standardized metrics (success rate, embedding error over unrolls, LPIPS of decoded frames); lesson modules on planner selection and context effects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability of compute; familiarity with transformer architectures; datasets like Metaworld, Robocasa, DROID.

- Rapid evaluation and selection of planners for specific task landscapes

- Sectors: robotics software, system integrators

- What to deploy now:

- Decision rule: use gradient-based (Adam/GD) for smooth, greedy-reaching tasks; use CEM L2 for multi-modal/non-greedy navigation; use NGOpt for quick cross-task generalization with minimal tuning.

- Tools/workflows: automated planner sweeps; convergence visualization (loss-per-iteration curves); fallback policies if local minima detected.

- Assumptions/dependencies: diagnostic tooling for loss landscape; adequate sampling budgets; accurate goal specification.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, or engineering to meet robustness, safety, and commercialization standards.

- General-purpose physical agents using latent-space planning across diverse tasks

- Sectors: household robotics, service robots, manufacturing, agriculture

- What could emerge:

- Unified JEPA-WM-based planners that transfer across manipulation, navigation, and scene types; multimodal extensions (language for goal specification, audio/tactile inputs) for rich task descriptions.

- Auto-tuning of context length W, multistep rollout depth, and planner hyperparameters via meta-learning across task families.

- Dependencies: larger and more diverse datasets; robust sim-to-real transfer; integration with closed-loop safety monitors; reliable proprioception alignment across embodiments.

- Digital twins for robotic cells with JEPA-based predictive planning

- Sectors: manufacturing, energy, infrastructure maintenance

- What could emerge:

- Latent world models that simulate cell dynamics for planning and predictive maintenance; non-greedy optimization for complex multi-step workflows; “plan in latent, verify in twin” pipelines.

- Dependencies: high-fidelity sensing and calibration; model validation against production data; tooling for constraint-aware planning (collision, force limits).

- Assistive and healthcare robotics with safer, goal-driven planning

- Sectors: healthcare, eldercare, rehabilitation

- What could emerge:

- JEPA-WM planning for assistive manipulators with image-defined goals and proprioception-driven precision near sensitive regions; semi-supervised learning from limited clinician-guided trajectories.

- Dependencies: rigorous safety certifications; robust perception in cluttered environments; domain-specific datasets; human-in-the-loop control frameworks.

- Autonomous mobile manipulation in unstructured environments

- Sectors: logistics, construction, disaster response

- What could emerge:

- Combined navigation and fine manipulation with non-greedy latent planning; AdaLN-enhanced action conditioning to keep control signals salient across longer horizons.

- Dependencies: scalable training on long-horizon tasks; integration with constraint solvers; real-time compute for sampling-based planners on edge hardware.

- Standardization and policy for reproducible world-model benchmarking

- Sectors: policy, standards bodies, research consortia

- What could emerge:

- Guidelines for reward-free data curation, evaluation protocols (success, embedding rollouts, decoded fidelity), and planner selection criteria; shared open datasets and leaderboards for latent planning.

- Dependencies: multi-institution collaboration; governance for responsible dataset release; environmental cost accounting for model training; safety assessment frameworks.

- Tooling and products: “Latent MPC” suites and AutoPlanner services

- Sectors: software tooling, robotics OEMs, integrators

- What could emerge:

- Commercial libraries bundling DINO encoders, predictor templates (AdaLN, sincos/RoPE), planner backends (CEM, NGOpt), and auto-selection heuristics; cloud services for training and evaluating JEPA-WMs on customer data.

- Dependencies: licensing for pretrained encoders; hardened APIs; performance guarantees under latency constraints; support for varying sensor/actuator interfaces.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Encoder-domain alignment: DINOv3 excels in photorealistic settings; DINOv2 may suffice for simpler/simulated environments; video encoders (V-JEPA) underperform on fine-grained spatial tasks here.

- Planner fit to landscape: gradient-based methods work for smooth goals (e.g., Metaworld reachers), while sampling (CEM/NGOpt) is better for multi-modal/non-greedy tasks (2D navigation, contact-rich manipulation).

- Context and rollout selection: Wp must not exceed W; W≈2–3 for simulated, W≈5 for real photorealistic; 2-step rollout helps in sims, up to 6-step helps in real data.

- Action-conditioning choice matters: AdaLN conditioning is strong and compute-efficient; feature/sequence conditioning preferences are task-dependent. Maintain reasonable action-to-visual dimension ratios to avoid signal vanishing.

- Real-world deployment: requires robust safety layers, constraint handling, closed-loop re-planning, sensor calibration, and domain adaptation to handle distribution shifts.

- Compute budgets: sampling-based planners demand parallel evaluation; real-time deployment needs careful horizon and batch sizing; NGOpt reduces tuning overhead but may converge slower than CEM.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.