The Prism Hypothesis: Harmonizing Semantic and Pixel Representations via Unified Autoencoding (2512.19693v1)

Abstract: Deep representations across modalities are inherently intertwined. In this paper, we systematically analyze the spectral characteristics of various semantic and pixel encoders. Interestingly, our study uncovers a highly inspiring and rarely explored correspondence between an encoder's feature spectrum and its functional role: semantic encoders primarily capture low-frequency components that encode abstract meaning, whereas pixel encoders additionally retain high-frequency information that conveys fine-grained detail. This heuristic finding offers a unifying perspective that ties encoder behavior to its underlying spectral structure. We define it as the Prism Hypothesis, where each data modality can be viewed as a projection of the natural world onto a shared feature spectrum, just like the prism. Building on this insight, we propose Unified Autoencoding (UAE), a model that harmonizes semantic structure and pixel details via an innovative frequency-band modulator, enabling their seamless coexistence. Extensive experiments on ImageNet and MS-COCO benchmarks validate that our UAE effectively unifies semantic abstraction and pixel-level fidelity into a single latent space with state-of-the-art performance.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces the Prism Hypothesis and a new model called Unified Autoencoding (UAE). The big idea is simple: think of all kinds of data (like images and text) as if they pass through a “prism,” which splits them into different “frequency bands.” Low frequencies capture the big picture and meaning (like what objects are in an image), while high frequencies capture tiny details (like textures and edges). UAE is designed to combine both—meaning and detail—into one shared representation so computers can both understand and recreate images better.

What questions does the paper ask?

The paper focuses on three easy-to-grasp questions:

- Do different kinds of AI encoders (semantic ones that care about meaning vs. pixel ones that care about detail) focus on different parts of the “frequency spectrum”?

- Can we prove that shared meaning mostly lives in the low-frequency parts of images?

- Can we build one model that keeps both the big-picture meaning and fine-grained details together, so understanding and generation work more smoothly?

How did they study it? (Methods explained simply)

To explore these questions, the authors did two things: they analyzed existing models and then built their own.

- Studying existing models:

- Imagine an image as a mix of “slow changes” (smooth color shifts—low frequency) and “fast changes” (sharp edges and tiny textures—high frequency). They used a tool like a “spectrum analyzer” (a Fourier transform) to measure how much energy each model puts into low vs. high frequencies.

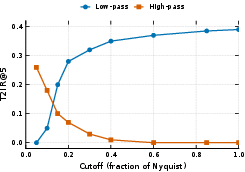

- They tested text–image matching while filtering images to keep only low frequencies (blurrier but meaningful) or only high frequencies (crisp details but less context). If meaning lives in low frequencies, text–image matching should stay strong with low frequencies and drop with only high frequencies—and that’s what they observed.

- Building UAE (Unified Autoencoding):

- Start with a strong “semantic encoder” (like DINOv2) that’s good at understanding what’s in an image.

- Split the internal image representation into multiple frequency bands: one low-frequency band for meaning, and several high-frequency bands for details. Think of it like separating an image into “blurry version” plus “layers of sharpness.”

- A “frequency-band modulator” gently mixes these bands back together, helping the decoder rebuild the image from both meaning and details.

- Train the model with two complementary goals:

- A “semantic-wise loss” that makes the low-frequency band match the teacher’s (DINOv2’s) understanding.

- A “pixel-wise reconstruction loss” that makes the full image look accurate and crisp.

- Add some controlled noise on high-frequency bands during training to make the decoder more robust to tiny variations.

In everyday terms: UAE learns to store “what it is” (low-frequency, semantic meaning) and “what it looks like” (high-frequency, fine detail) in one place, and it learns to rebuild images from both parts.

What did they find, and why is it important?

Main findings:

- Semantic encoders (like DINOv2, CLIP) mostly focus on low frequencies—great for recognizing categories and attributes.

- Pixel-focused encoders (like VAEs used in image generation) keep more high frequencies—great for fine detail.

- When they filtered images:

- Keeping low frequencies kept text–image matching strong.

- Keeping only high frequencies made matching drop to almost random. This supports the Prism Hypothesis: shared meaning lives in the low-frequency base.

UAE results:

- UAE strongly improves image reconstruction compared to similar “unified” models. It makes images sharper and more accurate while keeping the correct meaning. For example, compared to RAE (another approach using DINO features), UAE had much better numbers that indicate clearer and more true-to-original images.

- UAE is competitive with top autoencoders used in generative models (like Flux-VAE and SD3-VAE) in both how sharp images look and how faithful they are to the originals.

- UAE keeps strong semantic understanding. Even when tested with a simple classifier (linear probing), UAE matches or beats other methods, showing it didn’t lose the “what is it?” information.

- UAE is robust to how many bands you use. Whether they split the spectrum into 2 or 10 bands, performance stays stable. That means the idea is strong and doesn’t rely on tricky settings.

Why it’s important:

- It shows a clear connection between “what models learn” and “the frequencies they use,” linking image understanding and image generation under the same language of frequency.

- It provides a practical way to unify meaning and detail in one model, reducing conflicts between separate systems.

What does this mean for the future? (Implications)

- Better foundation models: UAE makes it easier to build systems that both understand and generate images using the same representation, leading to faster training and fewer mismatches.

- Clearer, more controllable generation: By organizing information from low to high frequencies, models can naturally generate images from “big picture” to “fine details,” potentially improving quality and control.

- Strong multimodal alignment: Since low-frequency bands carry shared meaning across modalities (like text and images), this approach could help unify more types of data (audio, video, sensors) without losing what makes each unique.

- Practical use: UAE’s frequency-aware design can be plugged into modern generative architectures (like diffusion transformers), helping them learn faster and produce better results.

In short, the Prism Hypothesis gives us a simple mental model—meaning lives in low frequencies, details live in high frequencies—and UAE turns that idea into a working system that makes both understanding and generation better at the same time.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a concrete, actionable list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper:

- Empirical scope of the Prism Hypothesis is narrow: validation is limited to 2D image encoders; no quantitative tests on text, audio, video, 3D, depth, or other modalities that the hypothesis claims to unify.

- Lack of rigorous statistical testing for the hypothesis: current evidence (energy distributions and retrieval under filtering) is correlational; no causality tests, invariance checks across datasets, or significance analyses across seeds/encoders.

- Ambiguity in retrieval experiments: datasets, exact encoders, prompt protocols, and chance baselines are not specified; robustness to different text encoders (e.g., CLIP vs. SigLIP) and corpora remains unknown.

- Frequency analysis methodology on ViT features is under-justified: applying 2D FFT on patch-token grids assumes translation/rotation properties ViTs don’t guarantee; the effect of patch size/stride on measured spectra is not analyzed.

- Radial mask design is fixed and hand-crafted: sensitivity to band boundaries, overlap width, cosine transition parameters, and non-radial (orientation-sensitive) masks is not studied.

- Overlap and invertibility are asserted but not proved: with overlapping masks and iterative residual subtraction, exact reconstruction guarantees are unclear; conditions for perfect partition vs. leakage are not provided.

- Band number robustness is shown, but band shape learning is not explored: could learned, content-adaptive, or anisotropic band decompositions outperform fixed concentric rings?

- No analysis of mutual information or disentanglement across bands: to what extent are low-/high-frequency bands statistically independent or crosstalk-free?

- Semantic-wise loss restricts alignment to the lowest band (K_base=1) without justification: sensitivity to K_base, or to distributing semantic supervision across multiple low bands, is not evaluated.

- The choice of teacher encoder is not studied: how do results change with different semantic teachers (e.g., CLIP, SigLIP, DINOv2 variants, supervised ViTs) or domain-specific encoders (medical/remote sensing)?

- Generalization to higher resolutions is untested: training/evaluation are at 256×256; behavior at megapixel resolutions (and scaling laws with resolution) is unknown.

- Cross-dataset generalization is limited: training on ImageNet-1K and evaluating on ImageNet/COCO leaves open questions about performance on out-of-distribution datasets and long-tail domains.

- Downstream task breadth is narrow: no results for detection, segmentation, dense correspondence, captioning, retrieval, or multimodal reasoning to support “unified” claims beyond reconstruction/generation/classification.

- Generative setup details are under-specified: the “causal” low-to-high band progression lacks ablations on schedule, steps, temperature, and conditionings; failure modes and error propagation across bands are not analyzed.

- Diffusion-friendliness is claimed but not deeply compared: convergence speed, NFE/sample efficiency, stability, and compute vs. quality trade-offs versus RAE/UniFlow/VAEs are not quantified.

- Compute and memory overheads are not reported: the cost of FFT band projection, iterative split, spectral transforms, and multi-band decoding vs. baselines is unknown.

- Noise injection is only applied to high-frequency bands with one scheme: impact of alternative corruption schedules, distributions, or per-band SNR targets is not explored; effects on robustness/adversarial sensitivity are untested.

- Reconstruction metrics may not capture perceived fidelity in text/line-art: no targeted benchmarks for small-text legibility, line art, or document fidelity (e.g., TextCaps/DocVQA-like proxies).

- rFID definition and protocol are unclear: how rFID is computed (feature network, preprocessing, splits) is not specified; comparison fairness to baselines may be confounded.

- Comparisons to SD3-VAE/Flux-VAE may be dataset-mismatched: training data scale and curation differences are not controlled; conclusions about competitiveness may be biased.

- Compression and rate–distortion trade-offs are unaddressed: how reconstruction/fidelity/semantics vary with latent ratio, band dropping (progressive transmission), or quantization is not studied.

- Editing and controllability potential is not demonstrated: although bands suggest controllable detail/semantics, the paper does not show band-wise editing, selective refinement, or conditional manipulation use cases.

- Extension to video is unexplored: spatiotemporal banding (3D FFT), temporal coherence, and motion semantics vs. detail separation are open questions.

- Robustness and safety are untested: sensitivity to low-frequency adversarial perturbations (which may flip semantics) and to high-frequency noise (which may degrade details) is unknown.

- Theoretical underpinnings are incomplete: no formal link between encoder objectives/architectures and their spectral allocation; no theory predicting when unified bands will improve generation or understanding.

- Training stability claims are anecdotal: convergence curves, seed variance, and failure cases (e.g., semantic collapse or overfitting to high-frequency noise) are not presented.

- Spectral transform block design is minimally explored: depth/width, attention vs. conv, or per-band cross-attention alternatives and their trade-offs are not ablated.

- Anisotropy and orientation-specific structure are ignored: radial bands cannot model oriented edges/textures; efficacy of oriented or steerable decompositions (e.g., Gabor/wavelet) remains open.

- Handling of CLS/register tokens and non-grid tokens is under-specified: how global tokens or non-spatial features fit into the frequency framework (or are excluded) is unclear.

- Practical deployment concerns are not covered: latency, throughput, memory footprint, and hardware efficiency on GPUs/NPUs for real-time applications are not reported.

- Ethical and societal impacts are not discussed: potential misuse in high-fidelity reconstruction/generation and dataset bias effects are not considered.

Glossary

- Alias-free synthesis: A signal-processing design in generative models that prevents aliasing artifacts at high frequencies. "alias-free synthesis to avoid spurious high-frequency artifacts"

- Autoregressive models: Generative models that produce outputs sequentially by predicting the next element conditioned on previous ones. "In autoregressive models, VAR casts generation as predicting the next scale or resolution"

- Cascaded diffusion: A multi-stage diffusion approach that trains models at progressively higher resolutions. "Cascaded diffusion trains models at increasing resolutions, allowing each stage to learn the appropriate frequency band and its own error distribution"

- Cosine similarities: A similarity measure between vectors based on the cosine of the angle between them. "we compute cosine similarities between text embeddings and image embeddings"

- Cosine transitions: Smooth mask boundaries implemented with cosine ramps to reduce artifacts in frequency-domain filtering. "both masks use cosine transitions to limit ringing artifacts"

- Coupling mechanism: An invertible transformation strategy used in flow-based generative models to split and transform variables. "Inspired by the coupling mechanism in flow-based models such as Glow"

- Discrete codebook methods: Tokenization techniques that quantize features into a finite set of discrete codes for generative modeling. "discrete codebook methods have demonstrated that the design and granularity of visual tokens play a crucial role"

- Discrete Fourier transform: A mathematical transform that converts spatial signals into their frequency components. "two-dimensional discrete Fourier transform"

- FFT Band Projector: A module that partitions features into frequency bands using Fourier masks and inverse FFT reconstruction. "using an FFT Band Projector followed by an Iterative Split procedure"

- Focal frequency loss: A loss function emphasizing difficult frequency components to improve reconstruction quality. "focal frequency loss to emphasize hard frequencies"

- Flow-based models: Generative models that use invertible transformations to map data to simple distributions. "flow-based models such as Glow"

- Fourier feature mappings: Input encodings using sinusoids to help networks represent high-frequency detail. "Fourier feature mappings and periodic activations that help multi-layer perceptrons represent fine detail"

- Frequency energy distribution: The allocation of representational energy across frequency bands in model features. "Frequency energy distribution"

- Frequency-band modulator: A component that separates and controls low- and high-frequency bands in latent representations. "via an innovative frequency-band modulator, enabling their seamless coexistence"

- GAN loss: The adversarial training objective used in GANs, often added to improve perceptual realism. "we finetune the full model end-to-end with noise injection and GAN loss"

- gFID: A variant of Fréchet Inception Distance used for evaluating generative model quality. "gFID and Accuracy metrics on ImageNet"

- High-pass filtering: Filtering that preserves high-frequency components while attenuating low-frequency content. "drops sharply under high-pass filtering, approaching random chance"

- High-pass masks: Frequency-domain masks that select high-frequency bands during spectral filtering. "high-pass masks of increasing cutoff (fraction of Nyquist)"

- Laplacian pyramid: A multi-scale representation that separates images into band-pass levels for coarse-to-fine synthesis. "A typical example is the Laplacian pyramid of adversarial networks"

- Latent grid: A structured tensor of latent tokens arranged in spatial grid form for downstream processing. "reshaped into a latent grid "

- Latent space: The feature space where compressed representations are encoded for reconstruction or generation. "within a single latent space"

- Linear probing: Evaluating learned representations by training a linear classifier on frozen features. "we perform linear probing on ImageNet-1K"

- Low-pass filtering: Filtering that preserves low-frequency structures while removing high-frequency detail. "remains stable under low-pass filtering"

- Nyquist: The maximum frequency that can be faithfully represented for a given sampling rate. "fraction of Nyquist"

- Patch-wise flow decoder: A decoder that reconstructs images using flow-based transformations applied per patch. "employs a lightweight patch-wise flow decoder"

- PSNR: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio; a fidelity metric measuring reconstruction quality relative to the original. "Here, we report PSNR and SSIM for fidelity"

- Radial mask: A frequency-domain mask defined by radius to select concentric frequency bands. "a smooth radial mask"

- Register tokens: Special tokens in ViT-like encoders used to aggregate or stabilize representations. "remove the register tokens"

- Representation Autoencoders (RAE): Autoencoders that train diffusion models on semantically rich latents from pretrained encoders. "Diffusion Transformers with Representation Autoencoders (RAE)"

- Residual branch: An auxiliary path that adds detail by learning residual signals on top of a base representation. "a small residual branch for details"

- Residual Split Flow: A decomposition procedure that iteratively splits latents into frequency bands via residual subtraction. "Residual Split Flow"

- Ringing artifacts: Oscillatory artifacts introduced by sharp spectral cutoffs or improper filtering. "to limit ringing artifacts"

- rFID: Reconstruction Fréchet Inception Distance; a perceptual quality metric for reconstructed images. "rFID, PSNR, gFID and Accuracy metrics"

- SiLU: A smooth nonlinear activation function (also known as swish) used in neural networks. "two layer convolutional block with SiLU"

- Spectral bias: The tendency of neural networks to learn low-frequency functions before high-frequency ones. "a phenomenon known as spectral bias"

- Spectral transform blocks: Decoder modules that refine residual frequency content before image reconstruction. "The decoder employs spectral transform blocks to refine residual-frequency content"

- SSIM: Structural Similarity Index; a perceptual metric assessing structural fidelity of reconstructions. "Here, we report PSNR and SSIM for fidelity"

- t-SNE: A nonlinear dimensionality reduction method for visualizing high-dimensional embeddings. "t-SNE visualization of semantic embeddings"

- Tokenizer: A model that converts images (or other modalities) into compact tokens/latents for unified processing. "a unified tokenizer that decouples continuous latent features"

- Unified Autoencoding (UAE): The proposed model that harmonizes semantic and pixel detail in one latent space via frequency factorization. "We introduce Unified Autoencoding (UAE), a tokenizer that learns a shared latent space and harmonizes semantic structure and pixel-level detail"

- ViT-based pixel decoder: A Vision Transformer-based decoder that reconstructs images from latent features. "decoded by the ViT-based pixel decoder"

- Zoomable pyramids: Multi-scale latent diffusion designs that share information across magnifications for large-image reconstruction. "zoomable pyramids that share information across scales"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

These applications can be prototyped or deployed now using the released codebase and standard ML stacks (e.g., PyTorch/Transformers), and they leverage the paper’s unified latent space and frequency-band modulator to separate “semantic structure” (low-frequency) from “fine detail” (high-frequency).

- Drop‑in unified tokenizer for diffusion/generative pipelines — software, media

- What: Replace VAEs with UAE to get semantically rich, diffusion‑friendly latents that accelerate convergence and improve fidelity (lower rFID, higher PSNR/SSIM).

- Tools/workflows: UAE encoder/decoder module as a VAE substitute in Diffusion Transformers, Stable Diffusion, DiT/RAE/UniFlow training scripts; Hugging Face model cards; ComfyUI/InvokeAI nodes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of DINOv2 weights and licensing; training recipes at 256×256 generalize to target resolutions; compute for FFT-based bands is acceptable.

- Progressive image transmission and preview via frequency bands — media/CDN, telecom, productivity

- What: Stream low‑band latents first for instant semantic preview; add residual bands for sharpness as bandwidth allows.

- Tools/workflows: UAE-based encoder on client; UAE/decoder service on edge/CDN; transport protocol sending band‑indexed payloads; integration with web viewers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sender/receiver must both support UAE; latency and packet ordering must preserve band order; currently validated for images (not video).

- Structure–texture disentangled editing — creative tools, design, marketing

- What: Edit global layout, color harmony, and object presence in low bands while preserving textures; conversely, retouch texture/denoise/sharpen via high bands without semantic drift.

- Tools/workflows: Photoshop/GIMP plugins; Blender/ComfyUI nodes exposing “semantic vs detail” sliders; localized band masks for region editing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robustness of edits across diverse content; UI and artist workflow design; licensing of pretrained teacher (DINOv2) used during training.

- Semantics‑preserving compression for archival/storage — cloud, MAM/DAM systems

- What: Compress images into UAE latents at similar ratios to VAEs with improved semantic faithfulness and detail recovery on decode.

- Tools/workflows: UAE encoder/decoder microservice; batch transcode pipelines; checksum/versioning support; optional GAN‑loss fine‑tuning for perceptual quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Storage/compute trade‑off vs existing codecs; standardization and bitstream specification for long‑term compatibility.

- Privacy‑tunable sharing (drop high‑frequency bands) — daily life, safety/compliance

- What: Share only low‑band latents to retain category/scene semantics while masking identity‑carrying textures (skin pores, unique patterns); reattach bands on trusted endpoints.

- Tools/workflows: “Safe share” mode in camera/scanner apps; server policies that strip or quantize bands 1+; audit logs capturing band levels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High‑frequency removal reduces but does not eliminate re‑identification risk; task-dependent validation is required; domain‑specific tuning for faces/documents.

- Robust retrieval and moderation using low‑band features — content platforms, search, trust & safety

- What: Use band‑0 embeddings for retrieval/moderation resilient to blur/compression; focus on semantics rather than superficial textures.

- Tools/workflows: Index band‑0 embeddings for image libraries; hybrid search that re‑ranks with higher bands when needed.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coverage demonstrated on ImageNet/COCO; additional calibration needed for domain‑specific taxonomies and adversarial content.

- Higher‑quality document scans and OCR pre‑processing — enterprise, gov, education

- What: Reconstruct crisp edges/text by selectively enhancing high‑frequency bands while stabilizing layout via low‑band constraints; reduce ringing/aliasing with smooth masks.

- Tools/workflows: UAE “clean‑up” filter before OCR; batch processing in digitization pipelines; on‑device scanner SDK.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model is trained on natural images; document‑specific fine‑tuning recommended; OCR vendor integration.

- Compute/bandwidth‑aware perception for robotics/AR — robotics, XR

- What: Run band‑0 only for fast semantic situational awareness; add bands 1+ for manipulation or fine alignment when time/compute permits.

- Tools/workflows: ROS node wrapping UAE encoder; policies that schedule band usage based on latency budget; AR alignment that progressively sharpens.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real‑time performance on target hardware must be profiled; current results at 256×256; motion/temporal stability for video not yet covered.

- Tokenizer for discriminative tasks — academia, ML platform teams

- What: Use UAE latents as inputs for linear probes/classifiers; maintain strong semantic discriminability (band‑0) while allowing detail‑aware branches.

- Tools/workflows: Feature extraction service; multi‑head training that reads band‑0 vs concatenated bands.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Task transfer measured on ImageNet; further validation for detection/segmentation required.

- Watermarking and forensic analysis by band targeting — media security

- What: Embed/read watermarks in designated bands to balance robustness vs imperceptibility; analyze edits by inspecting spectral band inconsistencies.

- Tools/workflows: Band‑aware watermark encoder/decoder; forensic dashboards that visualize band energy shifts across edits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Adversarial robustness needs testing; interaction with common post‑processing pipelines (resizing, JPEG) must be characterized.

Long‑Term Applications

These require additional research, scaling, domain adaptation, or standardization before broad deployment.

- UAE for video with temporal band factorization — media, streaming, surveillance

- What: Extend frequency bands to spatiotemporal domains for progressive streaming and generation (low‑band layout → high‑band motion/detail).

- Tools/products: Video UAE with temporal FFT or learned temporal filters; adaptive bitrate streaming that schedules bands/frame segments.

- Dependencies: Temporal stability, real‑time encoding/decoding, robust motion handling; new metrics beyond rFID/PSNR for video.

- Multimodal unified tokenizer (image–text–audio–3D) — foundation models, multimodal search

- What: Generalize the Prism Hypothesis to unify semantics across modalities in the shared low band while preserving modality‑specific high bands.

- Tools/products: Cross‑modal UAE backbone; band‑aware cross‑attention; retrieval/generation across modalities (e.g., text→image/video/audio).

- Dependencies: Modality‑specific masks and losses; large curated multimodal corpora; careful bias/safety evaluation.

- Semantic compression standardization (“JPEG‑S”) — standards, telecom

- What: Define an open bitstream where band‑0 carries semantics and residual bands carry detail; enable cross‑vendor interoperable decoders and progressive delivery.

- Tools/products: Reference codec; conformance tests; browser/OS‑level decoders.

- Dependencies: Standards bodies (JPEG, MPEG) involvement; IPR/licensing; hardware acceleration roadmaps.

- Hardware acceleration for band projectors and spectral transforms — chips, edge AI

- What: Implement FFT/band masking and spectral transforms in NPU/ISP pipelines to enable real‑time UAE on mobile/embedded.

- Tools/products: CUDA/TensorRT/Metal kernels; ISP firmware blocks; chip IP for alias‑free band splitting.

- Dependencies: Silicon design cycles; energy/latency benchmarking; co‑design with camera stacks.

- Medical imaging reconstruction and telemedicine — healthcare

- What: Semantics‑first teleconsults (band‑0) with on‑demand detail bands; reconstruction that preserves diagnostically relevant textures while aligning global anatomy.

- Tools/products: PACS plug‑ins; DICOM UAE transfer syntaxes; QA dashboards for band‑wise artifact checks.

- Dependencies: Domain‑specific training (MRI/CT/US); regulatory approval; rigorous clinician validation to avoid diagnostic loss.

- Autonomous driving: progressive perception and simulation — mobility, robotics

- What: Low‑band semantic situational awareness for planning; high‑band refinement for localization/HD‑map alignment; frequency‑progressive synthetic data for simulation.

- Tools/products: Band‑aware perception stack; simulator plugins producing band‑separable assets.

- Dependencies: Safety certification; robustness in adverse weather/night; scaling to high resolutions and multi‑camera rigs.

- Privacy‑preserving analytics with controllable disclosure — gov/policy, enterprise

- What: Share band‑0 only for analytics (counts, categories) while withholding identity‑bearing bands; grant tiered access to bands under policy.

- Tools/products: Policy engines tied to band levels; audit/compliance reporting.

- Dependencies: Formal privacy guarantees (e.g., empirical re‑ID studies, DP); governance frameworks and legal standards.

- Content authenticity and provenance via spectral fingerprints — policy, platforms

- What: Register spectral signatures at creation; detect tampering by anomalous band distributions; align with watermarking standards (C2PA).

- Tools/products: Band‑profiling SDK; platform‑side authenticity checks.

- Dependencies: Agreement on canonical band definitions; adversarial robustness research; standardization efforts.

- CAD/creative “semantic handles” for controllable generation — design, gaming

- What: Interactive edit stacks that bind semantic layout (band‑0) to nodes, with procedural texture layers in higher bands; faster iteration for concept art and assets.

- Tools/products: Game engine plugins; parametric design tools with band‑aware nodes.

- Dependencies: Larger‑scale UAE models at 1024–4K; UX studies for artists; asset pipelines integration.

- Energy‑efficient GenAI training/inference — energy, cloud

- What: Reduce training time and energy by operating in semantically rich low‑dimensional latents; schedule compute to bands by task difficulty.

- Tools/products: Band‑aware trainer that adjusts batch/steps per band; cloud instances with spectral kernels.

- Dependencies: Demonstrations at frontier scales; cost–quality benchmarking; scheduler research.

General assumptions and dependencies across applications

- Current results are reported at 256×256 on ImageNet‑1K and MS‑COCO; scaling to higher resolutions and long‑form content (video) needs further validation.

- The unified encoder relies on a pretrained semantic teacher (e.g., DINOv2); downstream performance inherits its biases and licenses.

- FFT/band operations add overhead; real‑time and mobile use cases will benefit from optimized kernels or hardware offload.

- The Prism Hypothesis is empirically supported for vision encoders; extensions to other modalities require new masks/objectives and datasets.

- Safety, privacy, and fairness require domain‑specific evaluations, especially where band suppression is used to manage identity or sensitive details.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.