Brain-Grounded Axes for Reading and Steering LLM States (2512.19399v1)

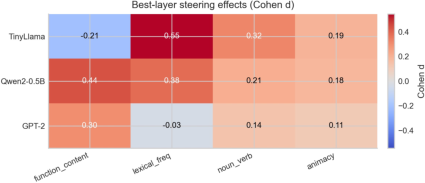

Abstract: Interpretability methods for LLMs typically derive directions from textual supervision, which can lack external grounding. We propose using human brain activity not as a training signal but as a coordinate system for reading and steering LLM states. Using the SMN4Lang MEG dataset, we construct a word-level brain atlas of phase-locking value (PLV) patterns and extract latent axes via ICA. We validate axes with independent lexica and NER-based labels (POS/log-frequency used as sanity checks), then train lightweight adapters that map LLM hidden states to these brain axes without fine-tuning the LLM. Steering along the resulting brain-derived directions yields a robust lexical (frequency-linked) axis in a mid TinyLlama layer, surviving perplexity-matched controls, and a brain-vs-text probe comparison shows larger log-frequency shifts (relative to the text probe) with lower perplexity for the brain axis. A function/content axis (axis 13) shows consistent steering in TinyLlama, Qwen2-0.5B, and GPT-2, with PPL-matched text-level corroboration. Layer-4 effects in TinyLlama are large but inconsistent, so we treat them as secondary (Appendix). Axis structure is stable when the atlas is rebuilt without GPT embedding-change features or with word2vec embeddings (|r|=0.64-0.95 across matched axes), reducing circularity concerns. Exploratory fMRI anchoring suggests potential alignment for embedding change and log frequency, but effects are sensitive to hemodynamic modeling assumptions and are treated as population-level evidence only. These results support a new interface: neurophysiology-grounded axes provide interpretable and controllable handles for LLM behavior.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper asks a simple but bold question: can we use real human brain activity as a kind of “compass” to read and gently steer what a LLM is thinking, without retraining the model? The authors build “axes” (think: sliders or dials) based on patterns measured from people’s brains while they listened to stories. Then they show that these brain-based axes can both explain parts of what LLMs represent and nudge LLMs to write in predictable ways.

What the researchers wanted to find out

- Can measurements from the human brain provide a stable, real-world reference system (a set of axes) to interpret the internal states of LLMs?

- Can we project an LLM’s hidden activity onto these brain axes to read what the model is focusing on (like word frequency or whether a word is a function word like “the” or a content word like “tree”)?

- If we push the LLM a little along one of these brain axes, will its writing change in a controlled, meaningful way, and stay fluent?

How they did it (in everyday terms)

First, some plain-language translations of key ideas:

- MEG: A brain scanning method (magnetoencephalography) that listens to tiny magnetic fields from the brain in real time, especially good for tracking fast changes while someone listens to a story.

- PLV (phase‑locking value): A measure of how “in sync” different brain sensors are, like checking if groups of dancers are moving together to the beat.

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A math method that takes a messy mix of signals and unmixes them into separate “source” directions—like separating the instruments in a song.

- LLM hidden states: The LLM’s internal “thoughts” as it processes words.

- Adapter: A small, simple model that translates from the LLM’s hidden states into the brain-axis scores—like a plug that lets two devices talk.

- Steering: Nudging the LLM’s hidden states a bit along one axis (like moving a slider) to change what it writes.

- Perplexity: A standard measure of how fluent or “natural” the text is; lower is better.

What they did, step by step:

- Collected brain data while people listened to natural stories. They chopped the data into small time windows and measured how synchronized different brain sensors were (PLV).

- Lined up these windows with the words in the stories. Using simple regression, they built a brain “atlas” at the word level: for each word type, an average brain-activity pattern.

- Unmixed the atlas with ICA to find key brain-based axes—directions that capture different kinds of word-related signals (for example, how frequent a word is, or whether it’s a function vs content word).

- Checked these axes against outside dictionaries and labels not used to build the atlas (like concreteness, animacy, and emotion ratings) to make sure the axes actually meant something real.

- Trained a lightweight adapter to map the LLM’s hidden states (from models like TinyLlama, Qwen2-0.5B, and GPT-2) onto these brain axes. Importantly, they did not fine-tune or retrain the LLMs.

- Steered the LLM by adding a small nudge along a chosen brain axis at specific layers in the network, then measured:

- Did the axis score move the way it should?

- Did the generated text change in the expected way?

- Did the text stay fluent (perplexity checks)?

- Did outside text labels (like part-of-speech) confirm the change?

They also ran careful controls to avoid “circularity” (accidentally using the same info twice), matched fluency between conditions, compared to text-only steering methods, and tested if results held across models.

What they found and why it matters

Main results in simple terms:

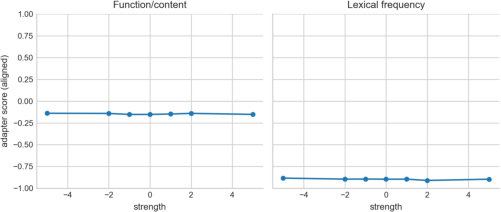

- A strong “frequency” axis: In TinyLlama, a mid-layer brain-based axis linked to word frequency let the authors steer the model to use words of different frequency in a controlled way. This effect survived strict controls, including matching text fluency.

- More efficient than a text-only probe: When they compared the brain-based frequency axis to a “text-only” probe built from word statistics, the brain-based axis shifted word frequency in the intended direction while making the text more fluent (lower perplexity). The text-only probe pushed in the wrong direction and made text less fluent. This suggests the brain-based approach provides a cleaner, more natural “handle” for steering.

- Comparable to a popular baseline, but with a twist: A standard steering method called Activation Addition (ActAdd) made an even larger frequency shift, but did not improve fluency. The brain-based axis made a big shift and improved fluency. The two directions were nearly orthogonal, meaning they capture different “ways” to change frequency—one more statistical, one more brain-like.

- A cross-model “function vs content” axis: Another brain axis reliably shifted models toward using more function words (like “the,” “and”) or more content words (like “cat,” “run”) in multiple LLMs (TinyLlama, Qwen2-0.5B, and GPT-2). This supports the idea that these brain-derived axes generalize beyond one model.

- Stability checks: Rebuilding the brain atlas without certain features (like GPT-based embedding change) still produced similar axes, reducing concerns that the method just mirrors text statistics. Some axes, like frequency, did depend partly on frequency features and were labeled “supervised” rather than “emergent.”

- Brain alignment evidence: Exploratory tests with fMRI hinted that some features (like frequency and embedding change) align with brain signals at the group level, though results varied by subject and depended on analysis choices.

Why this matters:

- It shows a new kind of interface between neuroscience and AI: using real brain patterns as coordinates to read and gently control LLMs.

- It can make steering more interpretable: instead of mysterious directions, you get axes grounded in how human brains respond to language.

- It may improve quality: brain-based steering sometimes made text more fluent while achieving the desired change.

What this could lead to

- More grounded interpretability: Researchers could study LLM internals using brain-based axes that reflect human processing, not just text labels.

- Better, safer control: If brain-grounded directions produce smoother, more natural changes, they could help guide models in useful ways without heavy retraining.

- Cross-model tools: Because the adapter is lightweight and the axes are fixed, the same brain atlas can help interpret and steer different LLMs, like using the same set of sliders on multiple devices.

Caveats and limits:

- The brain atlas was built in sensor space (which can be blurry), and some axes were influenced by features like word frequency. So not every axis is purely “semantic.”

- Some effects varied by model or layer, and a few results were less stable.

- fMRI anchoring was weak and sensitive to analysis choices.

- This is not mind-reading: the data are anonymous, and the steering effects are modest but reliable.

In short, the paper shows that brain-grounded axes can act like simple, understandable sliders that let you read and steer what an LLM is doing—often more cleanly and fluently than steering based only on text statistics. This opens a promising path for bridging how humans process language and how machines do.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated, actionable list of what remains uncertain or unexplored in the paper.

- Neuroimaging space and leakage: Validate all core results in source space (e.g., beamforming) with full leakage correction (e.g., symmetric multivariate leakage, iCOH), not just sensor-space PLV and limited wPLI subsets.

- Connectivity choice sensitivity: Systematically compare PLV to leakage-robust metrics (wPLI, imaginary coherence) and graph features; quantify how axis identities and steering effects change across metrics.

- Frequency-band generality: Derive and test axes across multiple frequency bands (delta, alpha, beta, gamma) and cross-frequency coupling to assess whether current theta-band axes are band-specific.

- Windowing and latency assumptions: Optimize time-window length, step, and word-alignment lags (beyond 0–1 s) with cross-validation; report how these choices affect axis stability and steering.

- Single-trial vs predicted PLV: Rebuild the atlas with denoised single-trial PLV (e.g., via trial-level shrinkage or denoising) to test whether axes persist without regression-predicted PLV states.

- Feature circularity in atlas construction: Construct an atlas without any text-derived features (no log-frequency, no POS, no LLM embeddings) and evaluate whether semantically interpretable axes still emerge and steer.

- Dependency on log-frequency supervision: For the frequency axis (axis 15), design supervision-minimized variants (e.g., weakly supervised or self-supervised brain-derived axes) and compare steering efficacy to quantify reliance on log-frequency features.

- ICA model order and stability: Perform model-order selection (e.g., profile likelihood, stability selection) for ICA; report axis stability across seeds/k values and compare to alternative decompositions (NMF, sparse coding, CCA).

- Spatial interpretability of axes: Localize axes to cortical sources/edges, identify contributing networks, and relate them to known language circuits (e.g., dorsal/ventral) to strengthen neurophysiological interpretability.

- Cross-subject and test–retest reliability: Quantify within-subject repeatability and between-subject variability; explore whether axes can be individualized and whether personalized axes improve steering or readout.

- fMRI anchoring robustness: Improve fMRI alignment by subject-specific HRF estimation, ROI-/parcel-level encoding, and cross-validated model selection; replicate on independent fMRI datasets to test population-level claims.

- External construct validity beyond POS/NER: Validate axes with independent, non-POS measures (e.g., psycholinguistic norms for syntactic complexity, semantic category, discourse status) to avoid using features present in atlas construction.

- Adapter expressivity: Test nonlinear and multi-layer adapters (e.g., MLPs, attention over layers) and compare to linear ridge for predicting brain axes; assess sample efficiency and overfitting risks.

- Tokenization and word alignment: Systematically evaluate subword-to-word aggregation choices across models (BPE vs word segmentation), and measure their impact on adapter accuracy and steering outcomes.

- Domain and language generalization: Train adapters on one corpus/language and evaluate on different domains/languages (including non-Chinese) to test cross-lingual and cross-domain robustness of the brain interface.

- Model scale and architecture effects: Extend cross-model tests to larger LLMs and different families (decoder-only vs encoder–decoder); analyze why GPT-2 lacks axis-15 steering while TinyLlama/Qwen-0.5B show it.

- Layer dependence mapping: Perform comprehensive, fine-grained layer sweeps (not just a small subset) to chart where each axis is most causally effective; assess consistency across prompts and seeds.

- Steering direction choice: Compare the current W_k-based direction to alternatives (e.g., gradients of axis scores, Jacobian-transpose projections, layerwise relevance) to identify directions that maximize target change with minimal side effects.

- Position- and component-specific interventions: Test localized steering (only specific tokens, attention heads, or MLP channels) to reduce off-target effects and clarify mechanistic loci.

- Dose–response and stability: Characterize nonlinearity, saturation, and reversibility across a wider range of strengths and contexts; evaluate stability across decoding strategies (greedy, nucleus sampling, temperature).

- Off-target effect auditing: Beyond perplexity and POS/NER, assess semantic coherence, factuality, toxicity, style, and long-range discourse impacts via human evaluation and task metrics (QA, summarization).

- Baseline breadth: Benchmark against stronger steering baselines (contrastive activation addition, rank-one model editing, representation null-space methods) and report efficiency/fluency trade-offs.

- Mechanistic causality: Use causal tracing/patching and head/MLP ablations to identify which circuit components mediate each brain axis’ effect and whether axes map to distinct functional subspaces.

- Axis composition and orthogonality: Quantify mutual interactions, orthogonality, and composability of axes; test whether multi-axis steering enables finer-grained control without interference.

- Data sufficiency and scaling laws: Probe how axis stability and steering strength scale with number of subjects, recording duration, and vocabulary size; determine minimal data for reliable axes.

- Broader stimuli and tasks: Validate axes using non-narrative stimuli (dialogue, instructions, code) and evaluate steering on downstream tasks to test ecological validity.

- Safety and bias: Investigate whether brain-derived axes encode demographic or cultural biases from the source population; evaluate fairness and transferability across populations.

- Privacy and personalization: Explore individualized axes for user-specific steering and assess privacy implications, including safeguards for preventing inference of sensitive traits.

- Reproducibility on independent datasets: Replicate the full pipeline on another synchronized MEG/fMRI language dataset to confirm that the axis geometry and steering effects generalize.

Glossary

- Activation Addition (ActAdd): An activation engineering method that steers model behavior by adding a vector difference between two activation sets. "Activation Addition (ActAdd) baseline"

- adapter: A lightweight mapping trained to project LLM hidden states into a target space without fine-tuning the base model. "train lightweight adapters that map LLM hidden states to these brain axes"

- animacy: A semantic property distinguishing animate from inanimate entities, used as an axis label. "the animacy axis (axis 2) is robust in the atlas"

- arousal: A psycholinguistic affective dimension reflecting intensity/excitability of words. "arousal (axis 15, , )"

- bootstrap confidence intervals: Resampling-based intervals estimating uncertainty of statistics. "We ran a rigorous reliability analysis with bootstrap confidence intervals"

- Cohen d: A standardized effect size measuring the difference between two means. "cell color encodes Cohen d; numbers show d values"

- contrastive vectors: Directions computed from contrasting activation sets to steer model representations. "Recent steering methods use activation-addition and contrastive vectors"

- cosine similarity: A measure of the angle-based similarity between two vectors. "cosine similarity $0.0104$"

- cross-model transfer: Testing whether mappings or effects generalize across different LLMs. "Cross-model transfer (Qwen2-0.5B)."

- cross-subject validation: Assessing whether effects replicate across different participant groups. "Cross-subject validation (odd vs even splits) shows 12 axis-dimension pairs replicating"

- cross-validation (CV): A model selection procedure that partitions data to tune hyperparameters and assess generalization. "alpha chosen by CV"

- edge-PCA: Principal component analysis applied to vectorized connectivity edges to reduce dimensionality. "compress the edge vector using PCA to 128 dimensions (edge-PCA)."

- encoding-based fMRI anchoring: Using predictive encoding models to relate features to fMRI responses for validation. "We ran an encoding-based fMRI anchoring test (ridge)"

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): A procedure to control the expected proportion of false positives in multiple testing. "We correct for multiple comparisons across layers and axes with FDR"

- field spread: Spatial smearing of electromagnetic signals across sensors in MEG/EEG, causing spurious connectivity. "The atlas is sensor-space and may include field spread"

- function/content ratio: A text-level metric comparing rates of function words to content words. "Function/content ratio: significant at layer 11 axis 13 (perm ; )"

- gradiometer channels: MEG sensor types that measure spatial gradients of magnetic fields. "on gradiometer channels"

- HRF (hemodynamic response function): A model of the blood-oxygen-level dependent signal’s time course in fMRI. "Using a 4~s peak HRF"

- hemodynamic modeling assumptions: Choices about HRF shape/timing that affect fMRI analyses. "effects are sensitive to hemodynamic modeling assumptions"

- ICA (Independent Component Analysis): A blind source separation method extracting statistically independent components. "We apply ICA to the averaged word atlas and obtain latent axes"

- L2-normalize: Scaling a vector to unit length using the Euclidean norm. "L2-normalize it"

- leakage-robust connectivity: Connectivity measures designed to reduce artifacts from spatial leakage in MEG/EEG. "leakage-robust connectivity"

- log-frequency: The logarithm of word frequency, used as a lexical variable and steering target. "log-frequency shifts"

- MEG (Magnetoencephalography): A neuroimaging technique measuring magnetic fields produced by neural activity. "preprocessed MEG sensor-level data"

- MNE-Python: A software toolbox for MEG/EEG data processing and analysis. "MNE-Python"

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Automatic identification and labeling of entities (e.g., persons, organizations) in text. "POS/NER metrics show partial external corroboration"

- Out-of-fold (OOF) predictions: Predictions generated on held-out folds to avoid training–test leakage. "Out-of-fold (OOF) atlas predictions preserve the axis geometry"

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis): A dimensionality reduction technique capturing maximum variance directions. "using PCA to 128 dimensions"

- perplexity (PPL): A language-model fluency metric measuring the uncertainty of predictions. "PPL-matched controls"

- phase-locking value (PLV): A measure of phase synchrony between signals across time. "We compute phase-locking value (PLV) in theta band (4--8 Hz)"

- Part-of-Speech (POS): Grammatical categories (e.g., noun, verb) assigned to words. "POS/NER metrics show partial external corroboration"

- residualization: Statistical control by regressing out confounds and analyzing residuals. "residualized "

- ridge regression: A linear regression with L2 regularization to mitigate multicollinearity and overfitting. "using ridge regression"

- representation engineering: Techniques that directly manipulate internal model activations to change behavior. "standard representation engineering"

- surprisal: The negative log probability of a word given context, capturing predictability. "logfreq+surprisal+length"

- theta band: A neural oscillation frequency range, here defined as 4–8 Hz. "theta band (4--8 Hz)"

- valence: An affective dimension indicating the pleasantness of words. "valence (axis 15, , )"

- wPLI (Weighted Phase Lag Index): A connectivity measure emphasizing non-zero phase-lag interactions to reduce leakage effects. "wPLI run (4 subjects, runs 10--20, decim=5)"

- word-level brain atlas: A mapping from words to aggregated brain-derived features or states. "word-level brain atlas"

Practical Applications

Practical Applications of “Brain-Grounded Axes for Reading and Steering LLM States”

The paper introduces a neurophysiology-grounded interface for reading and steering LLM hidden states via brain-derived axes (from MEG PLV connectivity with ICA), mapped using lightweight adapters and applied as inference-time activation shifts without model fine-tuning. Below are actionable applications that leverage the paper’s findings, methods, and innovations, grouped by deployment horizon.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be built now with open-source LLMs and the released codebase, assuming access to model internals (forward pass) to inject steering vectors.

- Readability control for consumer-facing text — [Education, Healthcare, Government, Finance]

- What: Use the frequency-linked axis (axis 15, TinyLlama L11) to steer toward higher-frequency (simpler) vocabulary for plain-language outputs (e.g., patient discharge instructions, public advisories, financial disclosures, consent forms).

- Tools/products/workflows: A HuggingFace Transformers middleware that adds an adjustable “reading level” slider (maps to α strength on axis 15) during generation; batch PPL-matched validation to maintain fluency; A/B testing vs. text-only probes/ActAdd.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Open-source LLM with hidden-state access; effect is strongest on mid layers (e.g., L11 in TinyLlama); currently validated primarily on Chinese-grounded atlases with cross-model evidence—language transfer may vary; simplification does not guarantee factuality.

- Style shaping via function/content control — [Marketing, SEO, Technical Writing, Software Documentation]

- What: Use the function/content axis (axis 13) to shift style toward content-heavy or function-word-heavy outputs (e.g., crisper executive summaries, more descriptive documentation).

- Tools/products/workflows: Editor plugin offering a style slider; plug into summarizers to tune density and terseness; PPL-matched checks to maintain fluency.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cross-model steering confirmed (TinyLlama, Qwen2-0.5B, GPT-2); POS cues partially used in atlas construction—treat as style control rather than purely semantic.

- Controlled simplification in translation and summarization — [Localization, Customer Support, Education]

- What: Post-hoc steering for simpler target-language outputs (axis 15), or content-density adjustments (axis 13) after MT/summarization decoding.

- Tools/products/workflows: Two-stage pipeline: decode → steer hidden states in a re-scoring or re-generation pass; deploy adaptive scripts per domain (e.g., FAQs vs. manuals).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires decoding-time intervention; language/domain mismatch with the atlas can reduce effect; ensure semantic fidelity with task-level constraints.

- Readability compliance checks and auto-correction — [Policy, Regulated Industries]

- What: Programmatic enforcement of readability (e.g., plain-language mandates) by auditing and nudging generation toward simpler lexicon with low PPL cost.

- Tools/products/workflows: CI-style guardrails for content pipelines; red-team harness using PPL-matched steering to pass readability gates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: PPL is a fluency proxy, not a guarantee of compliance; domain-specific thresholds must be calibrated.

- Neuro-grounded interpretability probes for model diagnostics — [Academia, ML Engineering]

- What: Use brain axes as externally grounded readouts to diagnose layer-wise representations, compare models, and detect regressions in updates.

- Tools/products/workflows: Evaluation suite that reads axis scores from hidden states (via adapters) across checkpoints/layers; report axis sensitivity vs. standard probes/ActAdd.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Axes are population-level (not subject-specific); some axes (e.g., animacy) validate strongly in the atlas but steer weakly in certain models.

- Safer representation engineering defaults — [Model Deployment]

- What: Prefer brain-derived steering over purely text-supervised vectors when fluency (PPL) costs matter; paper shows axis 15 improves PPL vs. text probe and matches ActAdd directions at lower PPL cost.

- Tools/products/workflows: Swap in brain-axis vectors for production “style knobs,” with guardrails using PPL and task metrics; multi-axis orchestration with orthogonality checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Effects are axis- and layer-specific; orthogonality with ActAdd suggests multiple subspaces—composability requires testing.

- Cross-model steering adapters as plug-in modules — [LLM Platforms, MLOps]

- What: Train lightweight ridge adapters per model (e.g., TinyLlama/Qwen/GPT-2) to map hidden states into brain axes, enabling a uniform control API across models.

- Tools/products/workflows: Model-agnostic “brain-axes adapter” SDK; CI to auto-tune layer/α per model with PPL- and task-level criteria.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires per-model calibration; GPT-2 showed weak/null effects on axis 15 but consistent on axis 13.

- Curriculum and reading support tools — [Education, EdTech]

- What: On-demand control of reading difficulty for leveled readers, assignments, and accessibility accommodations.

- Tools/products/workflows: Learning-platform plugin with per-learner readability targets; pair with lexical complexity meters; steer to hit targets with low PPL penalty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reading level is multi-factor; frequency is one component—pair with sentence structure controls.

- Analytics for neuro-aligned text generation — [Content Analytics]

- What: Track how outputs move along neuro-grounded axes over time (e.g., campaigns getting simpler/denser).

- Tools/products/workflows: Dashboard that logs axis-score distributions and PPL; alerts for drift.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Axis generality across domains is not guaranteed; recalibration may be needed.

- Research enablement: open datasets and code — [Academia]

- What: Replicate and extend with the released repo; build atlases from other corpora, examine cross-lingual axes, test leakage-robust metrics (wPLI).

- Tools/products/workflows: Standard MNE-Python + ICA pipeline; ridge adapters; reproducible config scripts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: MEG dataset and preprocessing conventions; robustness to field spread is partial; OOF controls mitigate circularity but don’t eliminate all confounds.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, language/domain adaptation, or access to additional neuro data.

- Multilingual neuro-axes libraries — [NLP Platforms, Academia]

- What: Build language-specific brain atlases (beyond Chinese) to enable reliable steering in diverse languages.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cross-lingual MEG/EEG/fMRI corpora; harmonized preprocessing; axis matching/alignment across languages.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data availability and ethics approvals; alignment methods for cross-language semantics.

- Personalized neuro-adapters — [Assistive Tech, Education, Healthcare]

- What: Subject-specific adapters that reflect individual processing (e.g., literacy level or aphasia-friendly outputs).

- Tools/products/workflows: Short, privacy-preserving EEG/MEG calibration sessions; federated training of adapters; on-device inference for privacy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong ethical safeguards; feasibility of low-cost/portable neuro recordings; subject-level stability remains to be shown.

- Real-time brain-in-the-loop text adaptation — [BCI, Accessibility]

- What: Dynamically steer content complexity based on real-time signals (EEG) indicating comprehension difficulty.

- Tools/products/workflows: Closed-loop pipeline: EEG → axis score proxy → adjust α during generation; latency-robust signal processing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real-time signal quality and decoding performance; robust HRF-free electrophysiology (EEG/MEG) pipelines.

- Neuro-grounded safety and alignment metrics — [Policy, AI Safety]

- What: Certification-style benchmarks using brain-aligned axes as external references for interpretability and controllability of LLMs.

- Tools/products/workflows: Standardized evaluation tasks and datasets; reporting requirements for neuro-aligned steering responsiveness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community consensus on metrics; reproducibility across labs; non-trivial policy/ethics vetting.

- Clinical communication optimizers — [Healthcare]

- What: Tailor clinical notes, after-visit summaries, and consent language to patient comprehension profiles while preserving clinical accuracy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Integration into EHR authoring tools; guardrails for medical correctness; audit trails showing axis-based steering.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain adaptation; medico-legal compliance; human-in-the-loop validation.

- Domain-specific neuro-axes (legal, scientific, technical) — [Enterprise, LegalTech]

- What: Build atlases from domain listening/reading tasks to expose axes reflecting domain-specific complexity, modality (equations vs. prose), or argumentation structure.

- Tools/products/workflows: Curated corpora and participant tasks; domain-informed labels for validation; adapters per model family.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Recruiting domain participants; task and stimulus design; potential IP/privacy constraints.

- Robust, leakage-immune neural grounding — [Neuro/NLP Methods]

- What: Scalable, source-space MEG/EEG or improved connectivity metrics (e.g., wPLI in larger cohorts) to reduce field-spread confounds and strengthen axis validity.

- Tools/products/workflows: Source localization, leakage correction, cross-lab harmonization; larger, multi-site datasets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data and compute; standardization across acquisition systems.

- Multi-axis, multi-objective controllers — [Production LLMs]

- What: Compose orthogonal axes (frequency, function/content, animacy, concreteness) with constraints (fluency, toxicity, factuality) for fine-grained control.

- Tools/products/workflows: Controller that selects layer/α per axis, enforces orthogonality and PPL budget, and monitors task metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Axis composability and independence; trade-off management across objectives.

- Neuro-aligned tutoring systems — [Education]

- What: Adaptive tutors that target cognitive workload by steering reading difficulty and content density in lessons and assessments.

- Tools/products/workflows: Student modeling; periodic calibration tasks; LMS integration with automatic difficulty-keeping.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ethical data use with minors; generalization across subjects and topics.

- Regulatory-grade explainability — [Policy, Compliance]

- What: Use external neuro-grounding to justify and audit controllability mechanisms in regulated deployments (finance, health, public sector).

- Tools/products/workflows: Documentation tying controls to brain-derived axes; third-party audits; standardized reporting templates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Acceptance by regulators; clear communication that axes are population-level and not individual diagnostics.

- Cross-modal extensions (vision, robotics language interfaces) — [Multimodal AI, Robotics]

- What: Explore whether neuro-grounded axes transfer to or inspire analogous control dimensions in multimodal encoders or policy networks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Build joint neuro-behavioral atlases for multimodal tasks; investigate controllable affordances via activation steering.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Suitable datasets; mapping from linguistic axes to multimodal representations is non-trivial.

Notes on Feasibility, Assumptions, and Dependencies

- Technical access: Immediate deployment requires open-source LLMs with hidden-state access; black-box APIs cannot be steered this way without vendor support.

- Layer/axis specificity: Effects are model- and layer-dependent (e.g., strongest at TinyLlama L11); calibration is needed per model.

- Language/domain transfer: Current atlas is derived from Chinese story listening; cross-model evidence exists, but robust multilingual/domain atlases will improve reliability.

- Metrics: Perplexity (PPL) is used as fluency proxy; gains do not guarantee factuality, safety, or domain correctness—pair with task-specific evaluations.

- Circularity and validation: The paper includes OOF, ablations, and brain-vs-text probe comparisons; POS-derived validations are not independent; fMRI anchoring is exploratory and sensitive to HRF assumptions.

- Ethics and privacy: Any personalized or real-time variants require stringent consent, privacy preservation, and clear communication that this is not individual mind-reading.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.