Classical billiards can compute (2512.19156v1)

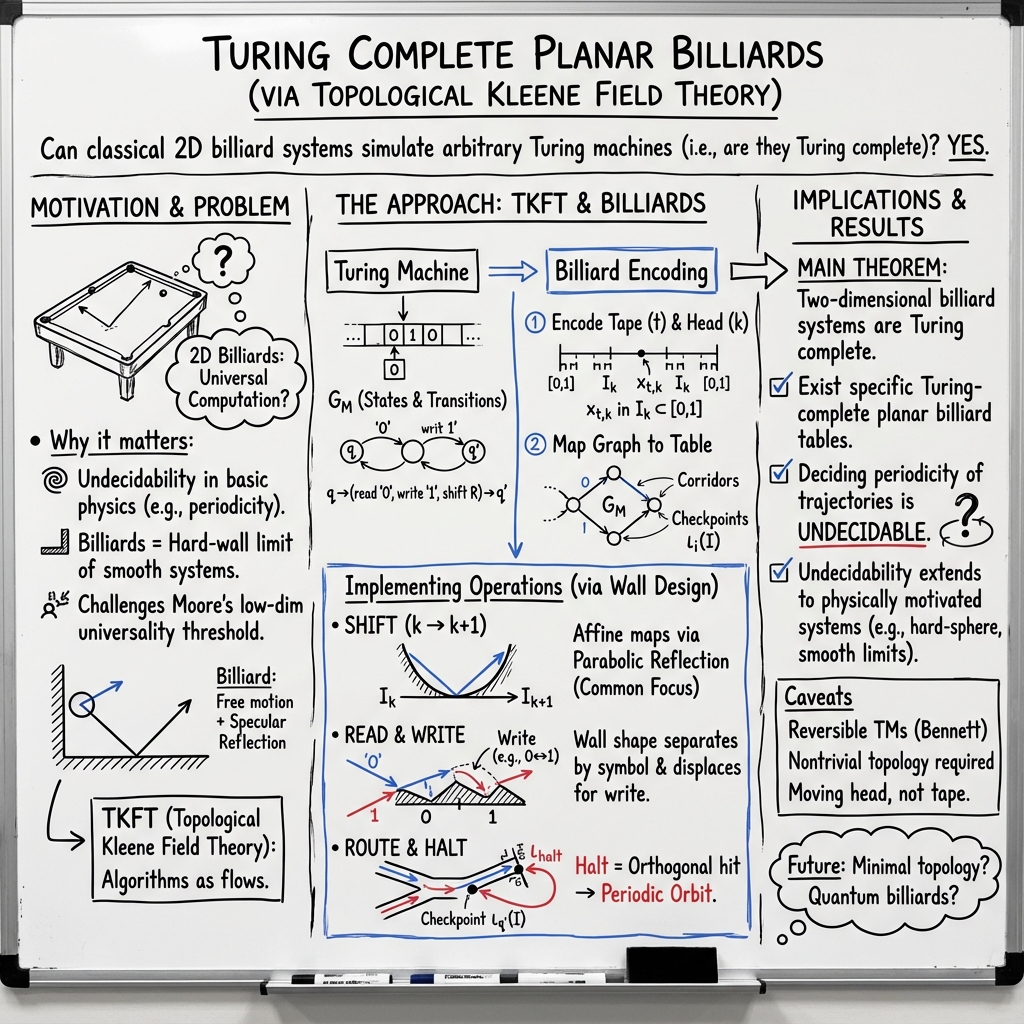

Abstract: We show that two-dimensional billiard systems are Turing complete by encoding their dynamics within the framework of Topological Kleene Field Theory. Billiards serve as idealized models of particle motion with elastic reflections and arise naturally as limits of smooth Hamiltonian systems under steep confining potentials. Our results establish the existence of undecidable trajectories in physically natural billiard-type models, including billiard-type models arising in hard-sphere gases and in collision-chain limits of celestial mechanics.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper shows a surprising idea: a simple-looking game of billiards (a ball bouncing off walls on a flat table) can be set up to do any computation that a computer can do. In other words, with the right shape of walls, one billiard ball moving in two dimensions can “compute” like a computer. The authors also explain why this means that some basic questions about such motion—like “Will the ball’s path repeat forever?”—cannot be decided by any general algorithm.

What questions did the authors ask?

They asked:

- Can a two-dimensional billiard system (one ball, fixed walls, ordinary reflections) simulate any computer program (a “Turing machine”)?

- If yes, which everyday questions about billiard motion become impossible to decide by a general procedure (undecidable)?

- Do these limits only apply to idealized hard-wall billiards, or do they also appear in real physics where billiards arise as limits of smooth systems?

How did they study the problem?

Think of three parts working together:

- A computer model they simulate: A Turing machine is a mathematical model of a computer. Picture a long tape of 0s and 1s, a “head” that reads one tape cell, writes 0 or 1, and moves left or right, plus a small internal memory called the “state.” If the machine reaches a “halt” state, the computation stops.

- Turning tapes into points on an interval: They need a way to carry the tape and head position into a physical system. They encode a tape and the head’s position as a single point on a line segment I (an interval). They do this by using a Cantor-set style ternary expansion (a way of writing a number using digits that pick out 0 or 1 in alternating places) and a tiny sub-interval for each possible head position.

- The tape’s 0s and 1s become digits in a number between 0 and 1.

- The head’s position k chooses which small sub-interval I_k the number sits in. This lets a single point x in the right sub-interval represent the entire computation state: “current tape” + “where the head is.”

- Building a billiard table that acts like a program: They design a billiard table whose walls guide the ball so that:

- A “shift” (move head left/right) is done by bouncing off parabolic walls that scale and shift the point along the interval as needed.

- A “read/write” operation is done by a carefully shaped wall that separates rays depending on whether the digit read is 0 or 1, and slightly adjusts the ray to change the digit when the machine says “write.”

- Each possible step of the Turing machine’s state graph (the finite-state diagram with edges labeled by read/write/shift) becomes a “corridor” in the billiard table. The ball’s ray travels through the corridor that matches the machine’s next instruction.

- The starting tape is placed on a special boundary interval (so the ball starts at the right point) and the halting condition corresponds to the ball hitting a specially marked halting interval orthogonally (straight on).

Under the hood, they use a mathematical framework called Topological Kleene Field Theory. You can think of it as a blueprint for turning computational steps into flows (motion) on shapes with boundaries, so that questions about the motion match questions about the computation.

What did they find and why is it important?

Main findings:

- Two-dimensional billiards are Turing complete. That means: for any Turing machine (any computer program), there is a flat billiard table (with fixed walls and one ball) whose bouncing trajectory simulates that program step-by-step.

- Undecidability shows up in billiards. Since the Halting problem (deciding in general if a program stops) is undecidable, the matching billiard question “Will this ball’s path reach the halting interval and bounce back, making a periodic orbit?” is also undecidable. So there cannot be a universal algorithm to decide if a given billiard trajectory is periodic on such a table.

- This is not just about idealized “hard-wall” tables. In regular physics, you can replace hard walls by very steep smooth potentials (soft walls). As these walls get steeper, the smooth motion approaches billiard motion. So these undecidability limits carry over to natural mechanical systems in a meaningful way.

- Related physical systems, like hard-sphere gases (many particles bouncing like billiards in a higher-dimensional space) and certain near-collision regimes in celestial mechanics (planets or asteroids passing very close) can inherit similar “symbolic dynamics.” This can make long-term behavior questions algorithmically undecidable, even though the equations are deterministic.

Why this matters:

- It adds a new kind of “limit to predictability” in classical mechanics, alongside chaos. Chaos says tiny changes grow and make prediction practically hard; undecidability says some questions don’t have any general algorithmic solution at all.

- It shows that very simple-looking physical systems can hide computational complexity deep enough to block certain predictions.

What does this mean for the future?

Implications:

- For mathematicians and physicists: Even low-dimensional, classical systems can encode computation so richly that some basic long-term questions (like periodicity or reachability) are undecidable. This reshapes how we think about “predicting the future” of deterministic systems.

- For modeling in physics: In kinetic theory, celestial mechanics, and smooth mechanical systems with steep boundaries, billiard-like descriptions can naturally occur. This suggests real-world scenarios where undecidability limits might matter, not just toy examples.

- For broader science: It invites us to look at the interface of geometry, dynamics, and computation. A bold open question is whether traces of this classical undecidability survive in quantum versions of billiards—possibly hinting at fundamental limits to prediction that cross the classical–quantum boundary.

In short: A cleverly designed billiard table can act like a computer. That’s fascinating by itself—but it also means that some simple-sounding questions about the ball’s path cannot be decided by any general algorithm. This reveals deep limits to prediction in systems we thought were well understood.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following list synthesizes what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide concrete future research:

- Formal geometric proof that the proposed parabolic-wall “affine” mappings (e.g., , ) are exactly realizable via specular reflection in two-dimensional billiards, with explicit analytic wall shapes and rigorous reflection-law derivations.

- Precise regularity requirements and construction details for the oscillatory “read–write” wall (smoothness class, curvature bounds, absence of corner singularities), ensuring the billiard flow is well-defined everywhere (unique normal and reflection).

- Treatment of digit-expansion ambiguities in the Cantor-like encoding (e.g., endpoints with multiple ternary representations) and a provable protocol to avoid or resolve these cases without breaking the simulation.

- Quantification and proof of reversibility’s role in “merging corridors”: a rigorous argument that distinct incoming computational paths do not accidentally coalesce without reversibility, and an explicit construction showing Bennett’s reversible embedding can be implemented in the billiard framework with bounded geometric overhead.

- Explicit bounds on the geometric complexity of the billiard table required for a given Turing machine (number of corridors, obstacles, total boundary length, curvature ranges), enabling complexity–geometry tradeoff analyses.

- Efficiency metrics of the simulation: provable bounds relating machine steps to number of reflections, path length, and physical time; identification of potential exponential slowdowns and whether polynomial-time geometries are achievable.

- Robustness to perturbations: formal structural stability results showing the computation survives small changes in wall geometry, initial angle, and starting point; identification of tolerance thresholds that still preserve correct read–write–shift behavior.

- Precise formulation of the undecidability result for periodicity: specification of the input class (e.g., computable boundary point and orthogonal initial velocity), formal reduction from Halting, and proof that the constructed non-halting trajectories are indeed aperiodic (not merely non-halting).

- Analysis of measure-theoretic typicality: characterization of the measure or category of initial conditions that encode valid tapes, and whether the undecidable set has positive measure or is meager/cantor-like.

- Avoidance and control of grazing trajectories: guarantees that the construction does not rely on near-tangential hits excluded from billiard–soft-wall convergence, and explicit geometric margins ensuring transversality of critical impacts.

- Soft-wall Hamiltonian realizations: a rigorous persistence result showing undecidability for sufficiently steep but finite potentials (not only in the limit), with quantitative convergence rates and error bounds that preserve the computational encoding.

- Hard-sphere gases: explicit embedding of the computational billiard as an invariant subsystem in realistic configuration-space boundaries (which are dictated by sphere collisions), including parameter regimes, constraints (e.g., , radii), and a constructive mapping.

- Collision chains in celestial mechanics: a concrete undecidability proof for a specific model (e.g., planar circular restricted three-body problem), including a full symbolic dynamics construction and parameter ranges under which undecidable trajectories provably occur.

- Polygonal vs. smooth billiards: whether universality can be achieved in purely polygonal tables (no curved walls), or under standard dispersing/focusing classes; identification of minimal geometric features needed (e.g., is curvature essential?).

- Topological complexity bounds: the remark poses an open question—establish lower/upper bounds on the number of obstacles needed versus the first Betti number of the Turing machine’s graph, and whether strict reductions are possible.

- Effectivity of the construction: an explicit algorithm that, given a Turing machine description, outputs a computable (e.g., piecewise analytic) specification of the billiard boundary, with complexity guarantees and numerical implementability.

- Handling larger alphabets and multi-track machines: extension of the encoding and read–write geometry beyond binary tapes and single-track heads, with precise geometric designs that scale gracefully.

- Elimination of “false positives”: a proof that no non-halting computation can inadvertently reach the halting interval orthogonally due to geometric coincidences or rounding effects; design constraints to ensure soundness of the halt–periodic mapping.

- Quantum billiards: a concrete research program to test whether classical undecidability survives quantization (e.g., non-computability of spectral gaps/eigenfunctions, semiclassical signatures), including precise decision problems and conjectures amenable to proof.

- Energy and time scaling: assessment of physical feasibility (e.g., whether reflection counts or path lengths lead to Zeno-like phenomena or impractically long times), and design modifications to avoid pathological slowdowns.

- Numerical/constructive exemplars: absence of a worked example (small Turing machine) with explicit boundary curves, ray-tracing verification, and error analysis; providing such examples would validate the method and guide implementation.

- Category-theoretic rigor: a full formalization of how Topological Kleene Field Theory maps into billiard flows (objects, morphisms, compositions), with precise theorems bridging the abstract TKFT constructions and the concrete geometric billiard encoding.

- Input encoding constraints: specification of how tapes map to computable boundary points (e.g., rational/recursive reals) and what precision is required to guarantee correct dynamical evolution; bounds on required accuracy per step.

- Noise and non-ideal reflections: models of friction, surface roughness, or slight wall motion, and proofs (or counterexamples) of computational robustness under realistic physical imperfections.

Glossary

- Affine transformation: A linear mapping followed by a translation that preserves points, straight lines, and planes. "These are affine transformations that can be realized using billiard walls with the form of parabolas sharing a common focus"

- Algorithmically undecidable: A property for which no algorithm can decide the outcome for all inputs. "It is algorithmically undecidable to determine whether the billiard trajectory starting orthogonally at is periodic."

- Betti number: A topological invariant counting the number of independent cycles; the first Betti number measures the number of “holes” in a space. "the first Betti number of the graph corresponding to the associated Turing machine"

- Billiard flow: The continuous-time dynamics of a particle moving freely inside a domain and reflecting at the boundary according to the billiard reflection law. "to the billiard flow in on finite time intervals."

- Billiard map: The discrete-time map taking successive collision points and directions along the boundary in a billiard system. "Since Birkhoff’s formulation of the billiard map, they have served as canonical models for Hamiltonian and symplectic dynamics with singular interactions"

- Binary collision manifold: The set of configurations where two bodies occupy the same position, representing collision states in celestial mechanics. " be a binary collision manifold."

- Cantor set: A totally disconnected, perfect, nowhere dense set constructed by iteratively removing middle thirds; used for encoding sequences. "The standard ternary Cantor set is the set of real numbers that can be written as"

- Celestial mechanics: The study of the motion of bodies under gravitational forces. "collision-chain limits of celestial mechanics"

- Collision chains: Sequences of near-collision segments approximating trajectories in the -body problem via matching conditions. "Collision chains can be characterized as critical points of a discrete Maupertuis action"

- Configuration space: The space of all possible positions of a system, often with constraints; billiard dynamics can be formulated in this space. "systems of hard spheres are equivalent to billiard flows in configuration space"

- Degenerate billiard approximation: An effective model where near-collision dynamics is approximated by billiard-like reflections on singular sets. "model near-collision motion using a degenerate billiard approximation in configuration space"

- Dispersing billiards: Billiards with strictly convex (dispersing) scatterers leading to hyperbolic behavior. "Sinai’s dispersing billiards provided foundational examples of hyperbolic and ergodic dynamics"

- Elastic reflections: Collisions where kinetic energy is conserved and the reflection angle follows the specular law. "with elastic reflections at the boundary of a domain "

- Ergodic dynamics: Dynamics where time averages equal space averages for almost all initial conditions. "foundational examples of hyperbolic and ergodic dynamics"

- Fixed-energy Kepler action: The action functional for Keplerian motion at a fixed energy, used in variational characterizations. "where denotes the fixed-energy Kepler action."

- Fundamental group: A group capturing the loops in a space up to deformation; measures first-order topological complexity. "for each of the generators of the fundamental group of the graph."

- Grazing trajectories: Paths that approach the boundary tangentially, complicating the billiard limit of smooth flows. "away from grazing trajectories"

- Hamiltonian flow: The evolution generated by Hamilton’s equations for a given Hamiltonian function. "the Hamiltonian flow converges (excluding trajectories that hit the boundary nearly tangentially) to billiard motion"

- Hard-sphere gases: Idealized systems where particles are rigid spheres colliding elastically. "including billiard-type models arising in hard-sphere gases"

- Hyperbolic dynamics: Dynamics exhibiting uniform expansion and contraction along invariant directions, typically with sensitive dependence on initial conditions. "foundational examples of hyperbolic and ergodic dynamics"

- Integrability: The property of a system having enough conserved quantities to allow exact solutions. "from complete integrability to strong chaos."

- Keplerian arcs: Segments of trajectories governed by Kepler’s problem (inverse-square gravitational force). "trajectories consist of Keplerian arcs joined by reflection-type matching conditions"

- Maupertuis action: A variational principle for classical mechanics relating trajectories to stationary action at fixed energy. "arising from stationarity of the Maupertuis action."

- Parabolic walls: Billiard boundaries shaped as parabolas, used to induce specific affine transformations of trajectories. "the shift arises naturally from reflections on parabolic walls"

- Piecewise smooth (class ): Boundary regularity assumptions where the boundary is smooth in parts and belongs to the -times continuously differentiable class. "one often assumes that is piecewise smooth, or of class ."

- Planar circular restricted three-body problem: A model where a massless body moves under the gravitational influence of two primaries in circular orbits, confined to a plane. "A concrete example is provided by the planar circular restricted three-body problem."

- Reversible Turing machine: A Turing machine whose global transition function is injective, allowing backward reconstruction of states. "For every Turing machine, there exists an equivalent reversible Turing machine."

- Semiclassical regime: The parameter regime bridging classical and quantum descriptions, often using asymptotic approximations. "in the semiclassical regime many features of the quantum dynamics are determined by the geometry and trajectories of the corresponding classical billiard"

- Soft-wall approximation: Modeling hard-wall billiard boundaries as steep smooth potentials so the smooth flow converges to billiard motion. "This soft-wall approximation embeds billiard dynamics within classical Hamiltonian mechanics"

- Specular reflection: Mirror-like reflection where the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. "reflects specularly from rigid walls."

- Strong deformation retract: A homotopy equivalence where a space continuously “retracts” onto a subspace while keeping points of the subspace fixed throughout. "the computational billiard created has as strong deformation retract the graph of the associated Turing machine."

- Symbolic dynamics: Encoding trajectories by sequences of symbols to analyze dynamical behavior via combinatorial methods. "The key tool for building a dynamical system capable of simulating a Turing machine is symbolic dynamics."

- Symplectic dynamics: The study of dynamics on symplectic manifolds, typically arising from Hamiltonian systems. "canonical models for Hamiltonian and symplectic dynamics with singular interactions"

- Teichmüller dynamics: Dynamics on moduli spaces of Riemann surfaces and flat structures, often linked to translation surfaces. "Teichm\"uller dynamics"

- Topological Kleene Field Theory: A computational framework encoding algorithms into dynamical systems on manifolds with boundary. "within the framework of Topological Kleene Field Theory."

- Translation surfaces: Flat surfaces with cone singularities obtained by gluing polygons; central in polygonal billiard dynamics. "translation surfaces"

- Undecidability: The impossibility of deciding certain problems algorithmically for all inputs. "undecidability, alongside chaos, as a fundamental obstruction to long-term prediction even in low-dimensional classical dynamics."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following near-term applications leverage the paper’s constructive encoding (Topological Kleene Field Theory adapted to billiards), the existence of Turing-complete 2D billiard tables, and the translation of halting/periodicity into billiard reachability.

- Academic research and teaching (mathematics, physics, CS)

- Use case: Course modules and lab demos illustrating universality, undecidability, and symbolic dynamics with “computational billiards.”

- Sector: Education and academia.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- CAD files for billiard tables implementing simple reversible Turing machines (e.g., parity checks, toggles).

- Interactive/VR simulators of billiard flows with “corridors” and parabolic walls realizing shift and read–write.

- Open-source scripts to turn a small reversible TM into a 2D billiard boundary specification.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Idealized specular reflections; careful fabrication/approximation of parabolic and piecewise-smooth walls.

- Reversible TM encodings to ensure invertible dynamics and merge/split corridor constructions.

- Benchmark problems for dynamical systems, verification, and numerics

- Use case: Stress-testing integrators, reachability analysis, and hybrid-systems tools with low-dimensional Hamiltonian systems known to exhibit undecidable properties (e.g., periodicity).

- Sector: Software (scientific computing), formal methods.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- A public repository of “computational billiard” instances with known reductions from halting/periodicity.

- Regression tests for numerical integrators in nonsmooth systems (impact maps) highlighting limits of algorithmic predictability.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Numerical simulations only approximate billiard dynamics; near-grazing impacts must be handled with care.

- Results are worst-case: specific instances may be decidable; tools must present guarantees accordingly.

- Risk communication and model governance for long-term predictions

- Use case: Communicating limits of long-term prediction for systems admitting billiard-type limits (e.g., collision-dominated celestial mechanics, hard-sphere approximations in kinetic theory).

- Sector: Policy, space agencies, climate/physical modeling governance.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Guidance documents and disclosure templates that distinguish guaranteed predictions from heuristic projections in billiard-like regimes.

- Model risk management checklists that flag undecidability in qualitative questions (e.g., “will this trajectory return/escape?”).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Physical regimes must plausibly reduce to or contain invariant subsystems with billiard-type dynamics; grazing trajectories and noise can invalidate the hard-wall approximation.

- Optical/microwave “ray-billiard” demonstrations

- Use case: Tabletop experiments in ray optics or microwave cavities demonstrating read–write and shift operations via shaped reflectors, to showcase reversible logic and universality.

- Sector: Photonics labs, physics education.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Billiard-inspired optical benches (parabolic mirrors for affine maps; segmented reflectors for symbol-dependent routing).

- Microwave cavity experiments (quantum billiard setups in the semiclassical regime) displaying complex itineraries linked to logic encodings.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Geometric (ray) optics or short-wavelength approximations must be valid; alignment tolerances and scattering losses need management.

- Security and randomness prototyping

- Use case: Physical unclonable function (PUF) or entropy-source prototypes leveraging sensitive dependence in billiard-like optical/microwave geometries to produce complex, device-specific responses.

- Sector: Hardware security.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Cavity shapes designed to induce complex path ensembles; enrollment/challenge-response characterization for device fingerprinting.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- The paper establishes universality/undecidability, not cryptographic strength; robustness under noise, stability, and reproducibility must be established experimentally.

- Robotics and automation: awareness in reflective/path environments

- Use case: Informing path-planning and coverage strategies in polygonal/reflective environments by recognizing that some reachability/periodicity questions are undecidable in principle.

- Sector: Robotics, autonomous systems.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Heuristic planners with conservative guarantees; emphasis on bounded-time verification and certificate-based approaches in reflective domains (e.g., inspection with lidar in mirror-rich spaces).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Direct reduction from the constructed billiard instances to specific robotic maps may be nontrivial; use primarily for setting expectations and designing safety margins.

Long-Term Applications

These applications build on the constructive framework but require further research, engineering, or scaling (e.g., noise robustness, fabrication, and soft-wall implementations).

- Reversible analog computing with billiard geometries

- Use case: Energy-efficient, reversible logic hardware using mechanical, optical, or acoustic “billiard gates” implementing shift and read–write via shaped boundaries.

- Sector: Hardware, energy-efficient computing.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- EDA-like toolchain that compiles reversible programs or finite-state machines to billiard boundary layouts.

- Hybrid optical-mechanical co-processors that exploit ray/particle trajectories for specialized tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Tolerance to fabrication errors, losses, and friction; synchronization; scalable reset/readout; managing near-grazing paths; coupling to digital systems.

- Microfluidic/colloidal or particle-based processors

- Use case: Structured microchannels with “billiard walls” to route particles for logic-like operations (lab-on-chip computation, embedded control without electronics in harsh environments).

- Sector: Microfluidics, robotics in constrained environments.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Lithographically patterned channels approximating billiard boundaries to implement simple reversible logic.

- On-chip readout via imaging or electrical sensing of particle positions.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Brownian motion and hydrodynamic interactions can disrupt ideal trajectories; requires error-correcting designs and robust encodings.

- Space mission design and space situational awareness

- Use case: Incorporate undecidability-aware workflows for mission planning in regimes with repeated near-collisions (e.g., small-body encounters) where collision-chain limits approximate billiard dynamics.

- Sector: Aerospace, astrodynamics.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Semi-decision and certificate-based strategies (prove existence/absence over bounded horizons; fallback to robust bounds).

- Operational policies emphasizing probabilistic risk and invariant-set computations over binary long-horizon claims.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Clear identification of regimes where collision-chain or steep-potential limits apply; control of model uncertainties and perturbations.

- Standards and regulatory frameworks for undecidability-aware modeling

- Use case: Formal standards that recognize algorithmic limits in qualitative predictions for certain physical models (e.g., hard-sphere kinetics, billiard-type Hamiltonians).

- Sector: Policy, standards bodies, agencies (e.g., ESA, NASA, NIST).

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Documentation standards specifying undecidability risk classes; validation criteria emphasizing bounded guarantees and explainable uncertainty.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Cross-disciplinary consensus on when billiard-type limits are relevant and how to communicate model limitations to stakeholders.

- Quantum billiards and quantum information devices

- Use case: Investigate whether traces of classical undecidability persist in quantum billiards; explore quantum devices or protocols exploiting complex billiard-derived spectra or scattering.

- Sector: Quantum information, condensed matter.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Experimental programs in mesoscopic “quantum dot” billiards and microwave cavities to probe computational complexity in spectral/transport features.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- The quantum persistence of classical undecidability is an open question highlighted by the paper; requires foundational research.

- Automated synthesis tools from logic to physical billiards

- Use case: End-to-end compilers that translate high-level reversible programs or Turing machines into manufacturable 2D billiard layouts (mechanical, optical, microfabricated).

- Sector: CAD/EDA, advanced manufacturing.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Constraint solvers ensuring noninterfering corridors, robust read–write wall design, and soft-wall potential approximations.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robustness to noise and geometry drift; scalable verification under physical constraints; integration with sensors/actuators.

- New verification paradigms for undecidable dynamical systems

- Use case: Develop semi-decision procedures, certificates, and probabilistic bounds tailored to systems where reachability/periodicity is undecidable in general.

- Sector: Formal methods, safety-critical systems.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Libraries computing invariant sets, barrier certificates, and bounded-horizon guarantees for nonsmooth Hamiltonian flows.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Requires bridging symbolic dynamics with convex optimization and measure-theoretic methods; acceptance of partial guarantees over absolute decisions.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.