VersatileFFN: Achieving Parameter Efficiency in LLMs via Adaptive Wide-and-Deep Reuse (2512.14531v1)

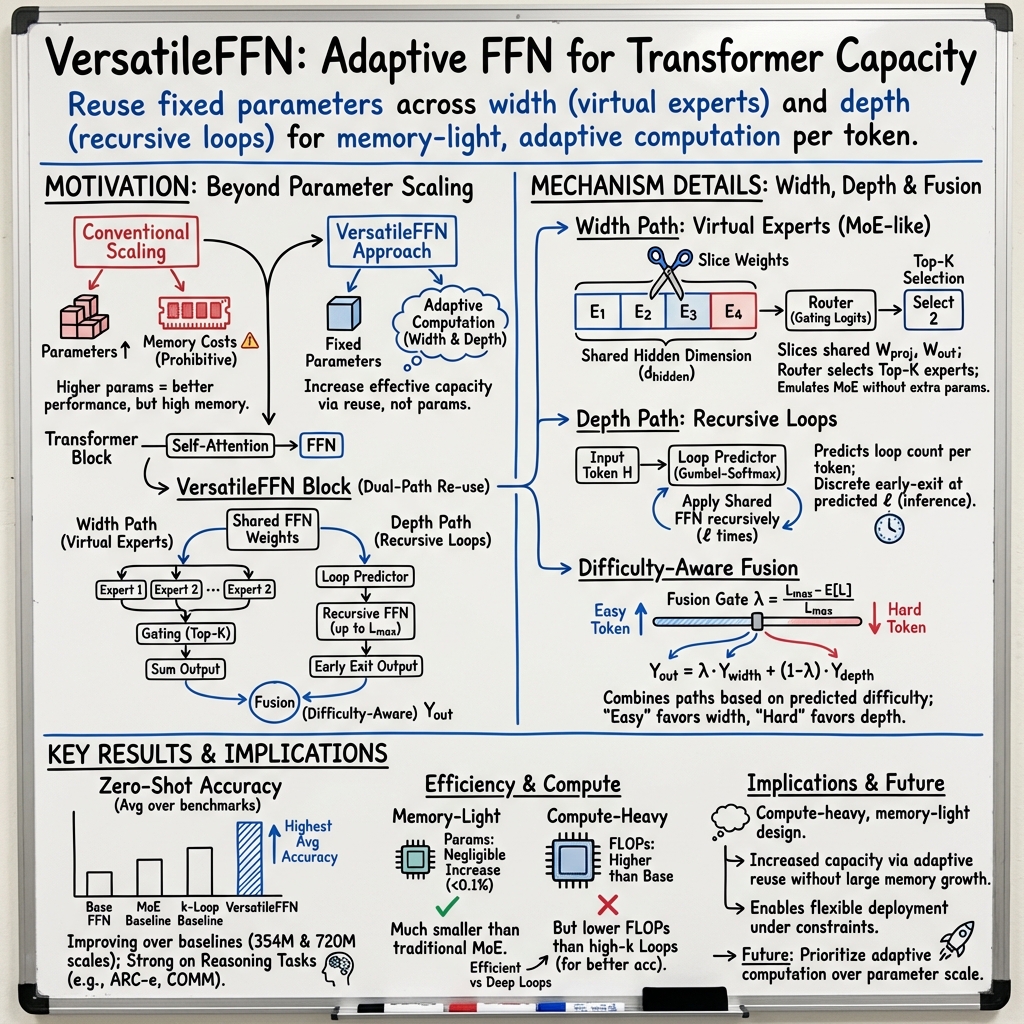

Abstract: The rapid scaling of LLMs has achieved remarkable performance, but it also leads to prohibitive memory costs. Existing parameter-efficient approaches such as pruning and quantization mainly compress pretrained models without enhancing architectural capacity, thereby hitting the representational ceiling of the base model. In this work, we propose VersatileFFN, a novel feed-forward network (FFN) that enables flexible reuse of parameters in both width and depth dimensions within a fixed parameter budget. Inspired by the dual-process theory of cognition, VersatileFFN comprises two adaptive pathways: a width-versatile path that generates a mixture of sub-experts from a single shared FFN, mimicking sparse expert routing without increasing parameters, and a depth-versatile path that recursively applies the same FFN to emulate deeper processing for complex tokens. A difficulty-aware gating dynamically balances the two pathways, steering "easy" tokens through the efficient width-wise route and allocating deeper iterative refinement to "hard" tokens. Crucially, both pathways reuse the same parameters, so all additional capacity comes from computation rather than memory. Experiments across diverse benchmarks and model scales demonstrate the effectiveness of the method. The code will be available at https://github.com/huawei-noah/noah-research/tree/master/VersatileFFN.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a new way to make LLMs smarter without making them much bigger. The authors propose “VersatileFFN,” a special part inside a Transformer (the kind of model used in LLMs) that reuses the same set of weights in two clever ways. This lets the model do more thinking using the same memory, which is important because super big models are hard and expensive to run.

Key Questions

The paper asks:

- How can we boost an LLM’s thinking power without adding tons of new parameters (which increases memory use)?

- Can we reuse the same weights in different ways—both “wide” (like many specialized mini-experts) and “deep” (like thinking multiple steps)—to handle easy and hard tokens differently?

- Will this “reuse” approach beat standard methods like Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) or simply repeating layers (“loops”) in accuracy and efficiency?

Methods and Approach

VersatileFFN replaces the usual feed-forward network (FFN) inside each Transformer block with two adaptive paths that share the same weights. In simple terms, think of it like using the same toolbox to do two kinds of work depending on how hard the job is.

What’s an FFN and a Token?

- FFN: A part of the model that transforms the information after attention. It’s like a “thinking” step that mixes and reshapes the features.

- Token: A chunk of text, like a word or a piece of a word. The model processes a sequence of tokens.

Path 1: Width-Versatile (many “mini-experts” from one FFN)

- Analogy: Imagine one big, experienced coach who can switch into different roles (like math coach, grammar coach, logic coach) without hiring new coaches.

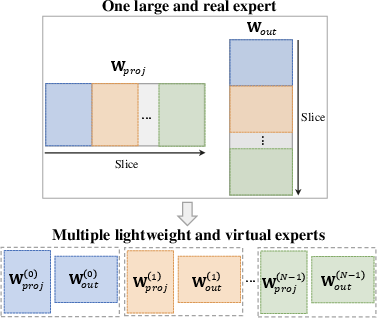

- How it works: The model slices the same FFN’s hidden space into several non-overlapping “virtual experts.” These are not separate sets of weights; they’re different views of the same big matrix.

- Routing: A small gating network looks at each token and picks the top few virtual experts best suited to handle it, similar to MoE—but without adding lots of new parameters.

Path 2: Depth-Versatile (think multiple times with the same FFN)

- Analogy: For harder tokens, the model “thinks” in several steps, reusing the same brain each time, rather than stacking new layers.

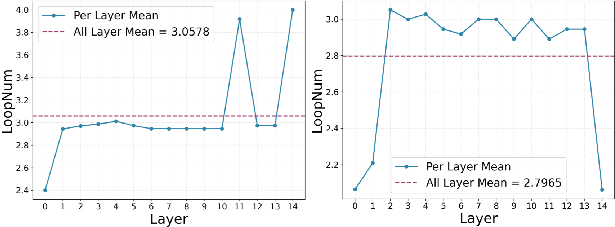

- How it works: The FFN is applied repeatedly to the same token representation—like going through revisions. The number of repeats (loops) is chosen per token.

- Choosing loops: The model predicts how many repeats a token needs using a method that’s trainable end-to-end (Gumbel-Softmax). During training, it keeps things smooth; at test time, it makes a firm decision, like “do 3 loops.”

Combining the Two Paths: Difficulty-Aware Fusion

- Analogy: A traffic director decides: easy tokens take the fast lane (width path), hard tokens take the slow lane with more thought (depth path).

- The fusion uses a number based on the predicted loop count. Fewer loops means “easy,” so the width path gets more weight. More loops means “hard,” so the depth path gets more weight.

- Important: Both paths use the same FFN weights. Extra ability comes from computation (doing more work), not memory (storing more parameters).

Main Findings and Why They Matter

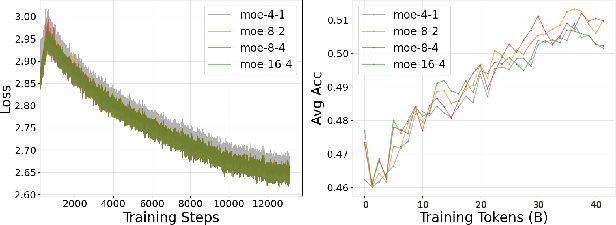

The authors test VersatileFFN on multiple language understanding and reasoning benchmarks (like PIQA, HellaSwag, ARC-e/c, CommonsenseQA, SciQ, and Winogrande) at two model sizes (~354M and ~720M parameters). Here’s what they find:

- Better accuracy under tight memory:

- At ~720M scale, VersatileFFN reaches about 57.03% average accuracy across tasks—higher than standard MoE (55.87%) and higher than repeating the FFN 6 times (“6-Loop,” 56.55%).

- Much less memory than MoE:

- MoE adds many new expert parameters (e.g., jumping from ~720M to ~1,145M). VersatileFFN adds less than 0.1% extra parameters for small controllers, because it reuses the same FFN weights.

- Smarter use of compute:

- Depth loops help with harder reasoning, but just adding more loops everywhere is wasteful. VersatileFFN’s adaptive approach spends more computation only where needed.

- In tests, 4 loops often gave the best balance between accuracy and speed.

- Real behavior insights:

- Smaller models tended to use more loops in later layers (more careful thinking at the end).

- Larger models used more loops in the middle layers (deeper processing in the middle).

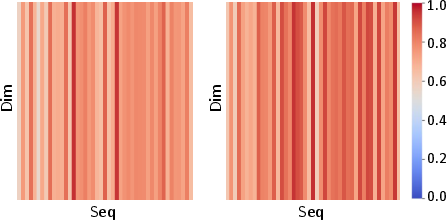

- Tokens like common filler words needed fewer loops; specific action words or trickier terms needed more loops.

These results matter because they show you can get better reasoning and accuracy without fitting a much bigger model into memory.

Implications and Impact

- Practical deployment: VersatileFFN is “memory-light.” It’s easier to run on limited hardware because it doesn’t rely on adding lots of new parameters.

- Smarter computation: The model adapts to the difficulty of each token, investing more “thinking time” where it pays off. That’s closer to how people think: quick reactions for simple stuff, deeper thought for hard problems.

- Better trade-offs: Instead of only scaling up model size, we can increase performance by reusing weights cleverly and allocating compute adaptively. This could inspire “compute-heavy, memory-light” designs for future LLMs, making them more accessible and efficient.

In short, VersatileFFN shows a promising path to make LLMs more capable by reusing the same tools in flexible ways, rather than carrying around a bigger toolbox.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, consolidated list of concrete knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper. These points aim to guide future researchers toward actionable follow-ups.

- Scaling beyond mid-size models: The method is only validated on 354M and 720M parameter models; it remains unclear how VersatileFFN behaves at 7B–70B+ scales and in production deployments where memory and throughput constraints differ substantially.

- End-to-end efficiency under realistic conditions: Reported FLOPs consider only FFN components for a single token; there is no end-to-end latency, throughput, wall-clock cost, or energy profiling on real hardware, nor an assessment under autoregressive decoding with KV-cache and batching.

- Actual memory footprint: While parameter counts are reported, there is no measurement of runtime memory usage (weights, activations, router states, loop states, and slicing views) during training and inference, especially for large batch sizes and long contexts.

- Distributed training and inference load balance: Adaptive loops and Top-K routing can cause device-level imbalance and stragglers; there is no analysis of scalability across multi-GPU/TPU clusters, inter-device communication overhead, or scheduling strategies to mitigate imbalance.

- Pretraining from scratch vs. continued pretraining: The method is evaluated mainly via one-epoch continued pretraining; it is unknown whether training VersatileFFN from scratch reaches similar or better convergence, stability, and generalization.

- Baseline breadth and strength: Comparisons omit several relevant parameter-sharing and adaptive-compute baselines (e.g., Universal Transformer, Mixture-of-Depths, LORY, ReMoE, HyperNetwork-based shared experts), leaving the relative advantage unclear.

- Task coverage and generalization: Evaluation focuses on eight multiple-choice benchmarks in zero-shot; impacts on generative tasks (math, code, long-form QA), few-shot/instruction tuning, chain-of-thought, multilingual benchmarks, and out-of-domain generalization are untested.

- Long-context behavior: Benefits for long sequences (>4k tokens), where recursive processing might help, are not examined; memory–compute trade-offs for long-context inference remain open.

- Difficulty proxy validity: The expected loop count is assumed to reflect token complexity; no calibration, correlation analysis, or external supervision verifies that reliably measures difficulty across tasks and layers.

- Fusion design: The fusion uses a linear scalar ; there’s no ablation of alternative fusion mechanisms (e.g., learned non-linear gating, per-dimension gates, attention-based fusion) or layer-wise fusion strategies.

- Virtual expert construction: Experts are static, non-overlapping slices of ; the paper does not explore learned or overlapping masks, rotations, permutations, or per-layer heterogeneity, nor does it quantify how much expressivity is lost vs. real experts.

- Interaction with SwiGLU and FFN shape: The effect of slicing on GLU-style activations (e.g., gate vs. value subspaces), hidden-size parity constraints, and potential interference is not analyzed; generality across other activations and norms (e.g., GeLU, LayerNorm) is unknown.

- Router specialization and interpretability: With shared weights across virtual experts, it is unclear whether routing yields meaningful specialization; metrics like expert diversity, mutual information, or specialization entropy are not reported.

- Loop predictor training dynamics: Sensitivity to Gumbel-Softmax temperature schedules, Straight-Through Estimator biases, convergence stability, and potential gradient pathologies (e.g., oscillations, collapse to single loop) are not studied.

- Recurrence stability and theory: There is no theoretical or empirical analysis of vanishing/exploding behavior across recursive FFN applications, conditions for stability, or formal expressivity bounds compared to deeper non-shared stacks.

- Compute budget control: The method lacks mechanisms to enforce global or per-sequence FLOPs/latency budgets at inference (e.g., adaptive per input, budget-aware gating), which is critical in resource-constrained deployments.

- Attention-side adaptability: The approach only modifies FFNs; whether similar width–depth versatility for attention (e.g., recursive attention or virtual attention experts) yields additional gains or adverse interactions is unexplored.

- KV-cache and decoding pipeline compatibility: The impact of per-token variable loops on KV-cache reuse, batching efficiency, and beam search/streaming pipelines is not evaluated.

- Hardware-level optimization: No discussion of custom kernels for recursive FFN application, view-based slicing, fusion, or memory locality; actual speedups or overheads on GPUs/TPUs (e.g., kernel launch costs, cache thrashing) are unknown.

- Activation checkpointing and training cost: Training-time memory/computation overhead from recursive states and dual pathways is not quantified; checkpointing strategies or mixed-precision effects are not discussed.

- Safety, robustness, and alignment: Impacts on safety (e.g., hallucination), robustness (adversarial or noisy inputs), or alignment (instruction-following, RLHF) are unaddressed.

- Multilingual and domain adaptation: Performance across languages, specialized domains (biomedical, legal), and low-resource settings remains an open question.

- When does width vs. depth help: The paper posits complementary roles but lacks systematic analyses linking task properties (e.g., syntactic vs. logical complexity) to optimal width/depth allocations across layers and tokens.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity and recipes: Sensitivity of , , , , router/loop regularization weights, and per-layer configurations is only lightly probed; there are no generalizable recipes for different model sizes or compute budgets.

- Reproducibility details: Some equations appear malformed (e.g., stride computation, index expressions), and practical slicing edge cases (non-divisible dimensions, alignment with GLU gates) are not clarified; exact implementation details for reliable reproduction are missing.

Glossary

- ALBERT: A Transformer variant that reduces parameters via cross-layer weight sharing to improve efficiency. "Early works such as Universal Transformers~\cite{dehghani2018universal} and ALBERT~\cite{lan2019albert} demonstrate that cross-layer parameter sharing can induce beneficial inductive biases and improve parameter efficiency for language modeling."

- Auxiliary load-balancing loss: A regularization term that encourages balanced expert utilization in MoE routing to avoid expert collapse. "Following previous experience~\cite{fedus2022switch}, we incorporate an auxiliary load-balancing loss during training to prevent expert collapse."

- Conditional Parallelism: An inference optimization that prunes negligible branches or runs pathways in parallel based on a threshold. "Conditional Parallelism: We employ a threshold-based execution strategy."

- Cross-layer parameter sharing: Reusing the same parameters across multiple layers to cut memory while preserving capacity. "Early works such as Universal Transformers~\cite{dehghani2018universal} and ALBERT~\cite{lan2019albert} demonstrate that cross-layer parameter sharing can induce beneficial inductive biases and improve parameter efficiency for language modeling."

- Depth-Versatile pathway: The branch that recursively applies the shared FFN to allocate more computation to harder tokens. "The Depth-Versatile pathway introduces token-wise adaptive computation by applying the shared MLP block recursively, enabling dynamic depth allocation."

- Discrete Early-Exit: An inference-time strategy that terminates recursion at the predicted step to avoid unnecessary compute. "Discrete Early-Exit: The Depth-Versatile pathway transitions from soft aggregation to a hard cutoff."

- Dual‑process theory of cognition: A psychological framework of fast (System 1) vs. slow (System 2) reasoning that motivates adaptive width-and-depth processing. "Inspired by the dual‑process theory of cognition, VersatileFFN comprises two adaptive pathways: a width‑versatile path ... and a depth‑versatile path ..."

- Expected loop count: A differentiable estimate of the required number of recursive steps per token used as a difficulty proxy. "We quantify this difficulty by computing the expected loop count, , derived from the soft probability distribution output by the loop predictor:"

- Gumbel-Softmax relaxation: A method to sample categorical decisions with a differentiable approximation during training. "We then employ the Gumbel-Softmax relaxation~\cite{jang2016categorical} to sample a differentiable probability vector :"

- LayerNorm: A normalization technique applied to token representations before attention or FFN to stabilize training. ""

- Mixture-of-Depths: An approach that adapts computational depth per input to allocate more “thinking time” to harder cases. "Methods like Mixture-of-Depths~\cite{raposo2024mixture}, Mixture-of-Recurrence~\cite{bae2025mixture} and Dynamic resolution network~\cite{zhu2021dynamic} dynamically allocate inference FLOPs, allowing models to expend more "thinking time" on harder tokens or images."

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): A sparse architecture that routes tokens to specialized experts to scale capacity without proportionally increasing computation. "The Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture serves as a foundational framework for scaling model capacity without a proportional increase in computational cost."

- Mixture-of-Recurrence: A method that mixes different amounts of recurrence per input for adaptive compute allocation. "Methods like Mixture-of-Depths~\cite{raposo2024mixture}, Mixture-of-Recurrence~\cite{bae2025mixture} and Dynamic resolution network~\cite{zhu2021dynamic} dynamically allocate inference FLOPs ..."

- Non-overlapping hidden subspaces: Disjoint slices of the hidden dimension used to form distinct virtual experts without interference. "each sub-expert is formed by selectively activating and composing different, non-overlapping hidden subspaces of the same underlying versatile FFN."

- Residual connection: A skip-connection that adds the input to the output of a layer to ease optimization and preserve information. "the input first undergoes a Self-Attention mechanism followed by residual connection and normalization:"

- RMSNorm: Root Mean Square Layer Normalization, a normalization variant used in Transformer models. "utilize SwiGLU for activation and RMSNorm~\cite{zhang2019root} for normalization."

- Router: A learned module that produces gating logits to assign tokens to experts in MoE-style routing. "Given the post‑attention token representation , a router computes the gating logits ."

- Self-Attention: A mechanism that computes token-to-token interactions within a sequence to build contextual representations. "the input first undergoes a Self-Attention mechanism followed by residual connection and normalization:"

- Straight-Through Estimator (STE): A training technique that uses discrete choices in the forward pass while backpropagating through a continuous relaxation. "We utilize the Straight-Through Estimator (STE) during training: the forward pass executes a discrete selection (via argmax) ... while gradients are propagated through the continuous relaxation ..."

- Strided slicing strategy: A method to construct virtual expert views by selecting parameter sub-blocks at uniform strides. "We employ a strided slicing strategy to map each expert to a specific view of the shared parameters."

- SwiGLU: An activation function that combines GLU-style gating with Swish for improved expressivity. "utilize SwiGLU for activation and RMSNorm~\cite{zhang2019root} for normalization."

- Top- strategy: A routing policy that activates only the top K scoring experts for each token to maintain sparsity. "We adopt a standard Top- strategy, activating only the experts with the highest routing scores."

- Universal Transformers: A recurrent Transformer architecture that shares parameters across steps to enable adaptive computation. "Early works such as Universal Transformers~\cite{dehghani2018universal} and ALBERT~\cite{lan2019albert} demonstrate that cross-layer parameter sharing ..."

- Virtual MoE: An MoE-like mechanism implemented by reusing sliced shared weights rather than instantiating separate expert parameters. "The Width-Versatile pathway, implemented as a virtual MoE, augments the model's representational capacity while circumventing the prohibitive memory overhead ..."

- Virtual experts: Experts defined as structured views of shared parameters (not separate weight matrices) to save memory. "We define a set of virtual experts by extracting structured, non-overlapping subspaces from the hidden dimension ..."

- Width-Versatile pathway: The branch that functions as a virtual MoE by routing tokens to sub-experts derived from shared FFN weights. "The Width-Versatile pathway, implemented as a virtual MoE, augments the model's representational capacity while circumventing the prohibitive memory overhead ..."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete use cases that can be deployed now or with modest engineering, taking VersatileFFN as a drop-in FFN replacement in Transformer blocks and leveraging its virtual experts (width) and recursive loops (depth) with difficulty-aware fusion.

- Sector: Software/AI infrastructure (model serving and MLOps)

- What: Lower-memory LLM serving on existing GPUs/CPUs with improved accuracy at nearly unchanged parameter count versus dense baselines.

- Why enabled by this paper: VersatileFFN shares one FFN across virtual experts and depth loops, increasing compute but avoiding MoE-style parameter bloat; inference optimizations include early-exit and conditional branch pruning.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- A Hugging Face Transformers/vLLM extension that replaces FFN with VersatileFFN, including a conversion script for existing checkpoints.

- A runtime controller to set max loops K, Top-K experts, and λ threshold for latency/SLO compliance.

- An observability dashboard that logs per-layer loop counts, λ distributions, and expert routing balance to detect collapse/imbalance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Minimal code changes needed: attention is unchanged; FFN replacement is local.

- Throughput depends on efficient kernels for per-token recursion and on parallel execution of width/depth branches.

- Scheduling dynamic loops may reduce GPU utilization without careful batching.

- Sector: Cloud cost optimization (providers and enterprises)

- What: Reduce inference memory footprint versus MoE while preserving or improving accuracy; consolidate deployments on smaller-memory accelerators.

- Why enabled by this paper: Virtual MoE via weight slicing avoids additional expert parameters; accuracy gains shown at 354M/720M scales with <0.1% parameter overhead.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- “Compute-heavy, memory-light” service tiers: choose higher FLOPs at lower memory cost for a given task mix.

- Autoscaling policies that adjust max loops per request based on queue depth or energy price.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Acceptable latency increase from added FFN FLOPs; early-exit settings tuned to keep tail latency within SLO.

- Sector: Edge/on-device AI (daily life, consumer devices, embedded)

- What: On-device assistants, summarization, and autocomplete that run within tight RAM budgets on laptops, tablets, and some smartphones.

- Why enabled by this paper: Adds capacity via compute reuse rather than parameters; enables higher capability without large weight files.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Offline note summarizers and email reply suggestion tools that fit within 8–16 GB RAM envelopes.

- Keyboard prediction using small LMs with VersatileFFN for better reasoning than same-size dense baselines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Battery/thermals must tolerate extra FLOPs; early-exit necessary for interactive latency.

- Mobile kernels must support token-wise recursion efficiently (or approximate via micro-batching).

- Sector: Healthcare (on-premise/air-gapped text applications)

- What: EHR note summarization, discharge instruction drafting, and on-prem clinical question answering on restricted servers without adding new GPUs.

- Why enabled by this paper: Improves capability at fixed parameter budget; avoids MoE parameter growth that strains secure, memory-limited environments.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Hospital IT deployments of mid-size LLMs enhanced with VersatileFFN for secure, compliant inference.

- Difficulty-aware inference where ambiguous clinical phrases automatically trigger deeper loops.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Domain adaptation still required; the paper’s results are on general NLP benchmarks.

- Validation against clinical safety standards and robust auditing of dynamic compute paths.

- Sector: Education (daily life and institutions)

- What: On-device tutoring, reading comprehension aids, quiz generation on student laptops/Chromebooks.

- Why enabled by this paper: Better reasoning performance without expanding parameters; works in constrained memory settings typical of school hardware.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Local classroom assistants with controllable “thinking time” via max loops.

- Teacher dashboards that visualize token “difficulty” (expected loop counts) to highlight confusing content.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Requires fine-tuning on educational tasks; multilingual generalization not validated in the paper.

- Sector: Customer support/contact centers

- What: Response drafting and intent classification with improved accuracy using existing serving hardware.

- Why enabled by this paper: Width-path virtual experts emulate topic specialization without storing many experts; depth-path refines hard cases.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- SLA-aware inference controller: low-complexity tickets run width-only; complex tickets trigger extra loops.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Router load balancing loss must be tuned to avoid expert collapse under non-stationary traffic.

- Sector: Security/compliance operations

- What: Policy-checking and content classification with dynamic “extra scrutiny” for ambiguous cases.

- Why enabled by this paper: Difficulty-aware fusion allocates deeper computation to uncertain tokens.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Audit trail exporting loop-count statistics for compliance reviews.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Needs calibration tying loop counts to uncertainty/risk metrics; not guaranteed by default.

- Sector: Research/academia

- What: Budget-constrained labs can attain better accuracy at the same parameter count; new testbeds for dual-process and recursive computation studies.

- Why enabled by this paper: Drop-in FFN replacement, open-source code (pending), explicit mechanisms for token-level difficulty and recursion.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Benchmarks using loop-counts as soft labels for difficulty; ablation studies on loop scheduling and expert slicing.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Code release and reproducibility; results shown for English zero-shot tasks and OLMo2 configs.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, system integration, or ecosystem support to be practical.

- Sector: Hardware–software co-design (accelerators and compilers)

- What: Chips and compilers optimized for token-wise dynamic loops and virtual experts with minimal control-flow overhead.

- Why enabled by this paper: Demonstrates value of per-token adaptive depth and shared-parameter width; motivates hardware support for early-exit and branch parallelism.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Compiler passes that fuse loop iterations and slice views; schedulers that co-run width and depth paths.

- Runtime APIs for variable compute-per-token within GPU/ASIC kernels.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Vendor support for fine-grained control flow and dynamic shapes; standardized kernels across frameworks.

- Sector: Multimodal and agentic systems

- What: Adaptive compute for complex reasoning steps (planning, tool-use) while keeping memory budgets fixed.

- Why enabled by this paper: Depth recursion aligns with “more thinking time” for hard cases; width virtualization can emulate modality- or tool-specific experts without storing many heads.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Planner modules that increase loops for long-horizon reasoning; virtual experts specialized to tools/APIs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Validation beyond text-only; new routing signals that incorporate vision/audio/tool context.

- Sector: Robotics and edge autonomy

- What: Onboard language-driven task planning with adaptive loops under strict memory budgets.

- Why enabled by this paper: Compute can scale with task difficulty while parameters remain small enough for embedded boards.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Controllers that raise loop counts when planning uncertainty spikes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Real-time constraints and hard deadlines; integration with perception/control stacks; robustness under distribution shift.

- Sector: Finance (low-latency, memory-constrained inference)

- What: Trading/research assistants running near data sources with limited memory but adjustable compute budgets.

- Why enabled by this paper: Memory-light MoE-like benefits plus loop-based depth for hard queries.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Latency-budgeted loop controllers tied to market regime detection.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Tight latency bounds require kernel-level optimization; careful risk controls for dynamic compute variability.

- Sector: Healthcare (regulatory-grade deployments)

- What: Certifiable adaptive-compute text systems with auditable difficulty signals and deterministic early-exit policies.

- Why enabled by this paper: Provides an interpretable scalar (expected loop count) that could inform human-in-the-loop oversight.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Governance layers that escalate to clinicians when loop counts exceed thresholds (proxy for uncertainty).

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Clinical validation, fairness/robustness studies; alignment with medical device regulations.

- Sector: Public sector and policy

- What: “Green AI” procurement emphasizing memory efficiency over parameter count, with compute budgets controlled via loops.

- Why enabled by this paper: Shifts the scaling frontier toward compute-heavy, memory-light designs that can reduce hardware sprawl.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Policy templates specifying per-token compute caps and audit of loop-count distributions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Standardized metrics for energy vs. memory trade-offs; measurement and reporting frameworks.

- Sector: Sustainability/energy-aware computing

- What: Carbon-aware inference that downshifts loops during grid stress or high carbon intensity while preserving functionality.

- Why enabled by this paper: Max loops and λ provide simple dials to trade accuracy vs. energy in real time.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Controllers integrated with data center energy APIs to schedule deeper loops in low-carbon windows.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Predictive models of accuracy impact from loop adjustments; SLO management strategies.

- Sector: Model compression and adaptation ecosystem

- What: New families of parameter-efficient designs combining VersatileFFN with pruning/quantization/LoRA.

- Why enabled by this paper: The architecture’s shared parameters and virtual experts are compatible in principle with compression and adapters.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Expert-aware quantization methods that respect sliced subspace structure; LoRA on the router/loop head.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- Joint training and calibration procedures; careful handling to avoid degrading virtual expert orthogonality.

- Sector: Interpretability and training science

- What: Curriculum learning and analysis using loop counts as a proxy for token difficulty; adaptive mixing of width/depth during training.

- Why enabled by this paper: Provides a measurable, learnable difficulty signal (expected loops) and a controllable fusion gate.

- Potential tools/products/workflows:

- Training schedulers that target harder tokens with more depth over time; dataset curation by learned difficulty.

- Assumptions/Dependencies:

- External validation that loop counts correlate with semantic difficulty across domains and languages.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Performance is demonstrated on English zero-shot NLP benchmarks with OLMo2; transfer to other languages, modalities, and much larger model scales requires validation.

- Gains come with higher FFN FLOPs; interactive use cases must tune early-exit and Top-K to meet latency/SLOs.

- Dynamic token-wise control flow can hurt hardware utilization without specialized kernels/batching strategies.

- Router and loop predictors must be trained carefully (e.g., load-balancing loss) to avoid expert collapse or unstable depth allocation.

- Compatibility with heavy quantization/pruning is promising but not guaranteed; expert slicing might complicate naive post-training quantization.

- The open-source implementation and reproducibility are prerequisites for broad adoption (the paper indicates code will be released).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.