Which Pieces Does Unigram Tokenization Really Need? (2512.12641v1)

Abstract: The Unigram tokenization algorithm offers a probabilistic alternative to the greedy heuristics of Byte-Pair Encoding. Despite its theoretical elegance, its implementation in practice is complex, limiting its adoption to the SentencePiece package and adapters thereof. We bridge this gap between theory and practice by providing a clear guide to implementation and parameter choices. We also identify a simpler algorithm that accepts slightly higher training loss in exchange for improved compression.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper looks at a way to split text into smaller pieces (called “tokens”) so computers can understand and learn from it. The method is called the Unigram tokenization algorithm. It’s a more math-based alternative to a popular method called Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE). The authors explain how Unigram really works, show which parts of it matter most, and offer a simpler version that’s easier to use and often compresses text more efficiently.

What were the researchers trying to find out?

They wanted to answer three main questions in clear, practical terms:

- How do you correctly implement the Unigram tokenization algorithm in real code?

- Which settings and steps actually affect how good the tokenizer is?

- Can we make a simpler version that trains faster and compresses text as well as (or better than) BPE, even if it slightly hurts the training score?

How did they do the research?

They carefully analyzed the original Unigram method and the popular open-source tool that uses it (SentencePiece). Then they tested different choices and settings on text in several languages (like English, German, Korean, Chinese, Arabic, and Hindi), measuring how well each choice worked.

Key ideas in simple terms

- Tokens and vocabulary: Imagine building sentences using LEGO bricks. Tokens are the bricks; the vocabulary is the box of bricks you’re allowed to use.

- Unigram vs. BPE:

- BPE starts with tiny bricks and greedily merges them into bigger bricks based on frequency.

- Unigram starts with many candidate bricks and assigns each a probability. It picks the split of the sentence that makes the overall probability highest.

- Probabilities: In Unigram, each token (brick) has a probability. A sentence’s score is like multiplying the probabilities of the tokens chosen for it. Higher probability means the tokenizer thinks that split is more sensible.

- Viterbi: A smart way to find the best split of a sentence (like finding the fastest route on a map).

- EM algorithm (Expectation-Maximization): A loop that:

- E-step: Estimates how often each token is used (considering all ways to split the text).

- M-step: Updates token probabilities based on those estimated uses.

- Seed vocabulary: The big starter set of candidate tokens. You prune (remove) weaker ones over time until you reach your target vocabulary size.

- Pruning: Like cleaning your LEGO box—keep the most useful bricks, remove the ones that don’t help much.

- Compression: Using fewer tokens to write the same text. Fewer tokens usually means faster models at inference time.

- Training loss (objective): A score of how well the tokenizer explains the text. Lower is better.

What did they change or test?

- A better way to build the seed vocabulary: Instead of scanning the whole text and sometimes rejecting good pieces because of spaces, they use pretokenization counts (think: tallying how often certain chunks appear) to choose strong candidates more reliably and efficiently.

- EM settings: They tried changing how many EM steps to run and whether to use certain mathematical tweaks (like “digamma”), and found these often don’t matter much.

- Pruning strategies:

- Standard Unigram pruning: Iteratively keeps tokens that help the probability score, removing those that don’t.

- Final-Style Pruning (FSP): A simpler idea—decide at the end mainly by token probability, without complex interactions. It’s faster and often compresses better.

What did they discover, and why is it important?

Here are the main findings:

- Many complicated defaults in common tools don’t change results much: Things like running multiple EM steps, using digamma transforms, or early pruning thresholds had minimal effect. This means you can simplify training and still get good results.

- A better seed vocabulary helps: Starting from pretokenization counts gave both better training scores and better compression than the traditional SentencePiece-style approach.

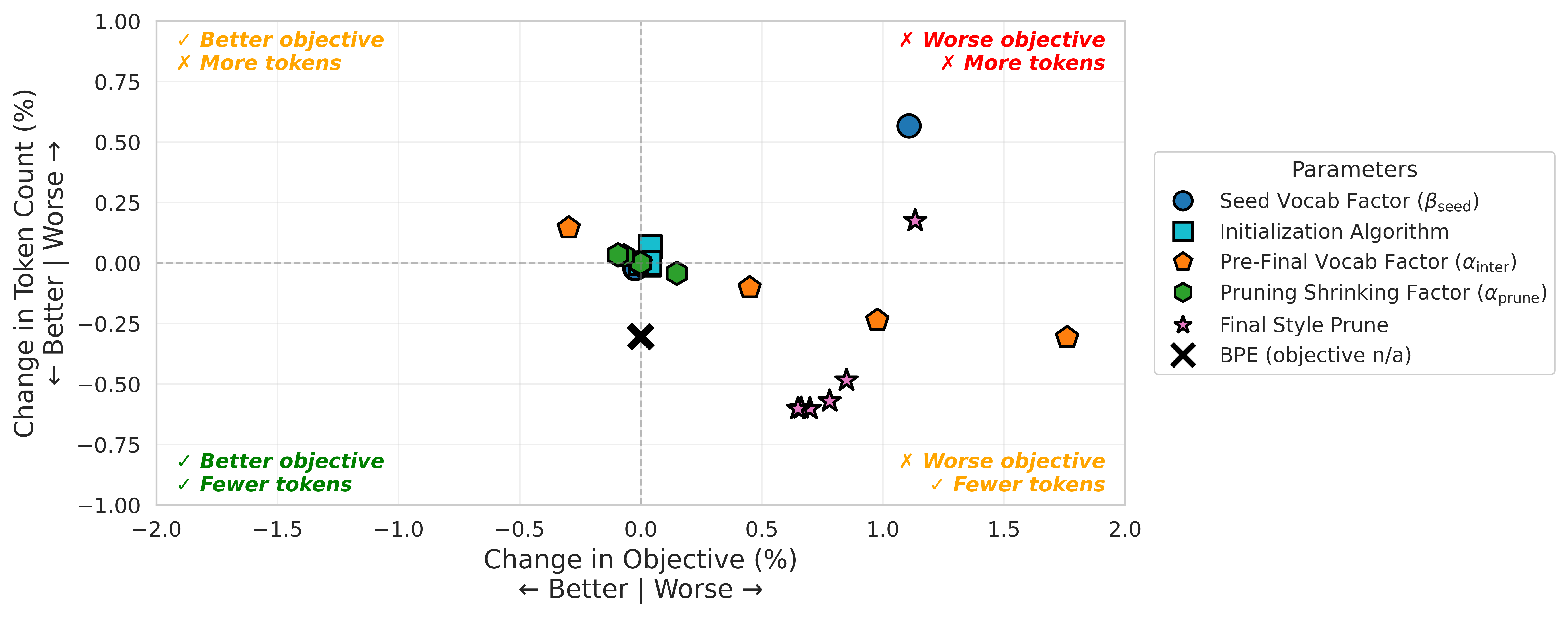

- There’s a tradeoff: You often can’t improve compression and the training score at the same time. If you compress better (fewer tokens per text), your training score (loss) tends to get a bit worse.

- The simple pruning method (FSP) is strong: FSP compresses as well as or better than BPE in many cases, but it slightly hurts the training score and is a bit worse at matching natural word parts (morphology) than standard Unigram.

- Out-of-domain generalization: When the tokenizer is trained on one dataset and tested on different text, BPE sometimes compresses a bit better. Still, Unigram typically does a better job at splitting words in ways that match real word parts across languages.

Why this matters:

- Faster, simpler training: You can train Unigram without worrying about lots of fiddly settings.

- Practical choices: If you care about speed and smaller token counts, the new simple pruning (FSP) is a great option. If you care about splitting words in a linguistically meaningful way (helpful for some languages and tasks), standard Unigram may be better.

What does this mean going forward?

- Unigram is sturdy and flexible: It works well even when you simplify many parts, which makes it easier for researchers and engineers to experiment with tokenizer design.

- Pick the right tool for the job:

- If your priority is speed and compact representations, consider Unigram with FSP—or even BPE for some out-of-domain cases.

- If you want better alignment to real word parts (which can help certain language tasks), standard Unigram is a strong choice.

- Bigger picture: Since tokenization affects how models understand text, clearer, simpler training methods can lead to better and faster language tools. This paper helps people move beyond treating tokenizers as black boxes and make informed design decisions.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper clarifies Unigram implementation and proposes Final-Style Pruning (FSP), but several issues remain open for future work:

Downstream effectiveness and generalization

- No evaluation of downstream LLM performance (perplexity, task metrics, alignment), leaving unclear whether intrinsic gains (compression, objective) translate to better models across sizes and training regimes.

- Unexplained out-of-domain behavior: BPE slightly outperforms Unigram/FSP in OOD compression; the causes (e.g., vocabulary stability, merge bias, inductive bias) remain untested.

- No analysis of inference/training efficiency impacts (wall-clock time, throughput, memory bandwidth) of compression gains versus FSP’s higher loss.

- Absence of robustness studies to domain shifts (code, math, URLs, noisy web, social media) and mixed-script data; current experiments are limited to six languages and Wikipedia-like text.

Metrics and tradeoffs

- The compression–objective tradeoff is observed but not theoretically explained; it remains unknown whether the Pareto frontier can be meaningfully shifted with alternative objectives, constraints, or regularizers.

- Intrinsic metrics only: lack of correlation analysis between objective/compression/morphological alignment and downstream model metrics across languages and domains.

- Morphological alignment evaluated only for English; cross-lingual morphology tradeoffs (especially for templatic, agglutinative, and unsegmented scripts) are not assessed.

Algorithmic design and theory

- FSP lacks theoretical analysis: no guarantees on likelihood degradation bounds, convergence behavior, or consistency relative to the original pruning procedure.

- The second-best tokenization heuristic (excluding the singleton path) is proposed but not benchmarked for exactness or complexity versus top-k algorithms across realistic corpora.

- EM-step choices (number of iterations, digamma transformation, early prune) show “minimal effect” empirically, but conditions under which they matter (e.g., highly skewed distributions, low-resource settings) are unspecified.

- The “early prune” threshold is corpus-size dependent; no corpus-size–invariant criterion (e.g., normalized by total tokens or Bayesian prior) is proposed or evaluated.

- No exploration of alternative probabilistic objectives (e.g., priors on token probabilities, structured dependencies beyond Unigram) that might improve both compression and objective.

Initialization and pretokenization

- Pretoken-based initialization is shown superior, but dependence on the specific pretokenization scheme (SCRIPT, character boundaries) is not analyzed; it is unclear how results change with other segmenters or in languages without clear word boundaries.

- Maximal Valid Prefix Recovery shows minimal effect at 30–300 MB; its utility in truly low-resource corpora (e.g., ≤5 MB) or highly specialized domains is untested.

- Seed vocabulary size is tuned around n=16–64K; behavior for very large vocabularies (e.g., 250k+) and very small vocabularies (<8k) remains underexplored, especially with SentencePiece-like defaults (~4× target size) at scale.

Coverage, fairness, and rare phenomena

- No analysis of rare characters, emojis, combining marks, numerics, and mixed-script tokens; the impact of FSP/initialization on rare-token coverage and training dynamics remains unknown.

- No investigation of under-trained or “glitch” tokens under Unigram vs BPE vs FSP (despite citing relevant prior work); implications for safety, reliability, and user-visible errors are open.

- No assessment of language equity: whether choices (pretokens, pruning, objectives) differentially benefit or harm low-resource languages and minority scripts.

Practical performance and reproducibility

- Computational profiling is missing: no wall-clock/runtime/memory comparisons among SentencePiece-style pruning, Unigram with baseline settings, FSP, and BPE at scale (≥1B tokens; distributed settings).

- Sensitivity to deduplication level and corpus duplication (which can affect expected counts and pruning thresholds) is not characterized; robust training procedures under different data hygiene pipelines are not proposed.

- Stability across random seeds and data order is not reported; variance in learned vocabularies, compression, and objective is unknown.

Tokenizer–model interaction

- Effects on subword regularization (sampling segmentations) are not tested for FSP or altered EM settings; consequences for regularization strength, sample diversity, and generalization are unknown.

- No exploration of tokenizer adaptation during model training (online or curriculum vocabulary updates) and whether FSP/initialization choices facilitate or hinder dynamic tokenization.

- Lack of guidance on selecting tradeoff points (compression vs objective vs morphology) given downstream constraints; no multi-objective training procedure or tuning protocol is proposed.

Evaluation scope and methodology

- Limited evaluation sizes (up to 1 GB FineWiki for cross-domain tests) and domains; large multilingual corpora and code-heavy datasets are not included.

- Reporting lacks uncertainty quantification: no confidence intervals, statistical significance tests, or multiple-run variability, making it hard to judge practical importance of small differences.

- MorphScore analysis is narrow (English only, recall only in the table); precision/F1 and qualitative cross-lingual segmentation analyses are absent.

These gaps suggest concrete next steps: conduct downstream LLM studies across domains and scales, formalize and analyze FSP’s properties, design size-invariant pruning criteria, probe low-resource and rare-token regimes, benchmark compute/memory at scale, assess cross-lingual morphology comprehensively, and develop multi-objective training schemes that better align tokenization with downstream goals.

Glossary

- Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE): A greedy subword tokenization method that iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent symbol pairs. "Byte-Pair Encoding."

- Digamma transformation: Applying the digamma function to expected counts to down-weight low-frequency tokens during parameter updates. "digamma transformation"

- Early prune step: A preliminary pruning in the M-step that removes tokens with very low expected counts before main pruning. "`early prune step'"

- Early prune threshold: The cutoff on expected counts used to trigger early pruning of tokens. "the early prune threshold"

- Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm: An iterative procedure alternating E-steps (computing expected counts over all segmentations) and M-steps (updating token probabilities). "the expectation-maximization algorithm"

- Final-Style Pruning (FSP): A simplified pruning strategy that selects the final vocabulary purely by token probabilities instead of interaction-aware iterative pruning. "Final-Style Pruning"

- Forward-backward algorithm: A dynamic-programming method to compute expected token counts over all possible segmentations under current probabilities. "the forward-backward algorithm"

- Longest prefix algorithm: An algorithm used with suffix arrays to identify the longest valid prefixes for candidate substrings. "a longest prefix algorithm"

- Marginal log-likelihood: The log-probability of the observed text marginalized over all tokenizations, used as the Unigram training objective. "marginal log-likelihood"

- Maximal Valid Prefix Recovery: A variant that reinserts the longest valid prefixes of otherwise rejected seed tokens during initialization. "`Maximal Valid Prefix Recovery'"

- Morphological alignment: The degree to which token boundaries align with morpheme boundaries in a language. "morphological alignment"

- MorphScore: A metric that quantifies morphological alignment by measuring boundary recall. "MorphScore"

- Pretoken-based initialization: Building the initial seed vocabulary using pretoken-to-count mappings to efficiently gather frequent substrings. "pretoken-based initialization algorithm"

- Pretokenization: Splitting raw text into preliminary units (pretokens) prior to subword learning to constrain candidate tokens. "pretokenization with character boundaries"

- SCRIPT encoding: A structured encoding and pretokenization scheme that respects Unicode script boundaries across languages. "SCRIPT encoding"

- Second-best tokenization: The next-best segmentation for a token’s text used to estimate the impact of removing that token. "second-best tokenization"

- Seed vocabulary: The large initial set of candidate tokens from which the target vocabulary is pruned. "Seed Vocabulary Initialization"

- SentencePiece: A widely used reference implementation of Unigram (and BPE) tokenizers that standardizes training and inference procedures. "SentencePiece implementation"

- Shrinking factor: The fraction of tokens retained at each pruning iteration, controlling how gradually the vocabulary reduces. "shrinking factor"

- Stack-based emission algorithm: A method that scans suffix-array/LCP structures with a stack to emit frequent substrings efficiently. "stack-based emission algorithm"

- Subword regularization: Training with sampled alternative segmentations to improve robustness and linguistic consistency. "subword regularization"

- Suffix array: A compact index of all suffixes of a string used for fast substring frequency computation. "a suffix array"

- Top-k tokenizations: The k highest-probability segmentations of a text under the current model. "top tokenizations"

- Unigram LLM: A tokenization model assuming independence between tokens, assigning probabilities to tokens and segmentations. "The Unigram LLM for tokenization"

- Viterbi algorithm: A dynamic-programming algorithm that finds the highest-probability segmentation under the current token probabilities. "the Viterbi algorithm is typically used"

- Vocabulary pruning: Iteratively removing low-utility tokens to reach a target vocabulary size while preserving likelihood. "Iterative Vocabulary Pruning"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable use cases that can be deployed today, derived from the paper’s clarified algorithms, simplifications, and empirical findings.

- Faster, simpler Unigram tokenizer training for LLM pipelines

- Sector: software/ML tooling, cloud

- What: Adopt the paper’s simplified defaults (e.g., 1–2 EM iterations, omit digamma, insensitive early-prune threshold), which the authors show have minimal effect on outcomes.

- Tools/Workflows: Integrate

script_tokor equivalent into data preprocessing; add a “Unigram (fast)” option to tokenizer training CLIs; plug into Hugging Face tokenizers pipelines. - Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to corpus; Viterbi decoding implementation; acceptance that intrinsic metrics are proxies and downstream verification is needed.

- Pretoken-based seed vocabulary initialization for higher quality and speed

- Sector: software/ML tooling, multilingual NLP

- What: Use pretoken-to-count mappings with suffix arrays to initialize seeds, producing better compression and objective versus SentencePiece-style full-text extraction; set seed factor α≈10× target vocab size.

- Tools/Workflows: Replace SentencePiece-style init with pretoken-based init; include SCRIPT pretokenization with character boundaries for robust multilingual training.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of pretokenization; sufficiently large corpora mitigate “Maximal Valid Prefix Recovery” needs; adjust default seed size (many SP defaults are too small for large multilingual vocabs).

- Compression-first tokenizer for latency- and cost-sensitive inference via Final-Style Pruning (FSP)

- Sector: mobile/edge, consumer apps, enterprise chat

- What: Use FSP to prune by token probabilities instead of iterative interaction-based pruning when token count (and thus inference latency/cost) is the priority; often matches or exceeds BPE compression, with slightly higher Unigram loss.

- Tools/Workflows: Add a “compression mode” flag that switches to FSP; measure tokens-per-input and latency improvements in A/B tests.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Potential reduction in morphological alignment and out-of-domain generalization; requires domain-specific validation.

- Morphology-aware tokenization for MT and linguistically rich languages

- Sector: translation, ASR, education

- What: Prefer standard Unigram (not FSP) to retain higher MorphScore (better morphological boundary recall), aligning with subword regularization benefits.

- Tools/Workflows: Enable Unigram sampling at training time; track MorphScore in tokenizer/model eval dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Gains depend on language morphology; verify with downstream MT/NLP tasks.

- Rapid domain adaptation tokenizers (finance/legal/code/biomed)

- Sector: finance, legal, healthcare, software (code)

- What: Retrain Unigram tokenizers efficiently on domain corpora using the simplified pipeline to capture domain-specific subwords and improve compression and coverage.

- Tools/Workflows: “Tokenizer retrain” MLOps job triggered by domain drift; cache pretoken counts; export vocab + merges/probs for downstream.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Quality and representativeness of domain corpus; tradeoffs vs BPE out-of-domain behavior.

- Tokenizer A/B testing and health dashboards

- Sector: MLOps/ML infra

- What: Systematically compare configurations along compression, Unigram objective, and MorphScore; track regression and drift across versions/languages.

- Tools/Workflows: CI jobs that train/evaluate tokenizers nightly; dashboards with tokens-per-document, marginal log-likelihood, MorphScore; alerts on degradation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Standardized eval corpora; awareness that intrinsic metrics don’t always predict downstream metrics.

- Cost and energy savings in data pipelines

- Sector: cloud/compute, green AI

- What: Reduce tokenizer training time and complexity (e.g., fewer EM passes, simpler pruning), lowering compute cost and energy for frequent retraining in large orgs.

- Tools/Workflows: Cost reporting in pipeline runs; flag “fast mode” for exploratory training.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Savings are material mainly for teams that retrain tokenizers often; end-to-end LM training still dominates total cost.

- Open-source teaching and reproducibility

- Sector: academia/education

- What: Use the paper’s clarified steps and code to teach Unigram, reproduce SentencePiece behavior, and run controlled experiments on tokenizer design.

- Tools/Workflows: Course labs; research baselines that toggle seed init, pruning, and EM settings.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Curriculum integration; availability of multilingual corpora.

- Policy- and fairness-oriented diagnostics for tokenizers

- Sector: policy/standards, NGOs, public sector

- What: Include MorphScore and script coverage in model cards to surface language equity and morphological alignment choices.

- Tools/Workflows: Tokenizer fairness checklist; publish metrics per language/script.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community acceptance of metrics; appropriate multilingual evaluation sets.

Long-Term Applications

These applications may require further research, scaling, or ecosystem development before broad deployment.

- Joint tokenizer–model training and dynamic vocabulary learning

- Sector: research, foundation models

- What: Co-optimize Unigram objective with LM training; adapt vocabulary as training progresses or per domain.

- Tools/Workflows: Training frameworks that support online segmentation sampling and periodic vocab updates; model–tokenizer co-checkpointing.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Significant algorithmic and systems work; stability and convergence questions; retraining costs.

- Adaptive tokenization at inference time

- Sector: mobile/edge, accessibility, enterprise

- What: Switch between FSP-like compression (for latency/constrained devices) and morphology-preserving Unigram (for linguistic quality) per user/device/task.

- Tools/Workflows: Runtime tokenizer selection; compatibility layers to unify embeddings across tokenizations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Models robust to multiple tokenizers or need distillation/alignment; added complexity in deployment.

- Standardized tokenizer evaluation suites and guidelines

- Sector: policy/standards, industry consortia

- What: Establish benchmarks that include compression, marginal log-likelihood, and MorphScore across languages and domains; publish tokenizer “model cards.”

- Tools/Workflows: An open benchmark and leaderboard; governance for test sets and metrics.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community buy-in; maintenance and dataset licensing.

- Multilingual equity by design (SCRIPT pretokenization and seed sizing)

- Sector: global tech, public sector, localization

- What: Codify practices that reduce disparities (e.g., SCRIPT pretokenization, adequate seed size α for large multilingual vocabularies).

- Tools/Workflows: Language coverage audits; pre-deployment reviews of tokenizer settings.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Acceptance that tokenization impacts representation; organizational commitment to audits.

- AutoTokenize systems: constraint-aware tokenizer selection/tuning

- Sector: MLOps/AutoML

- What: Automated selection of Unigram/BPE/FSP and hyperparameters based on latency, memory, language mix, and domain constraints.

- Tools/Workflows: Optimizers that explore the compression–objective–alignment frontier; suggest configs with tradeoff explanations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate cost/latency and quality predictors; access to representative eval data.

- Tokenizer health monitoring in production (drift and retraining policies)

- Sector: enterprise AI operations

- What: Detect drift in token distributions and morphology alignment; trigger retraining or vocabulary expansion.

- Tools/Workflows: Telemetry pipelines; privacy-preserving token statistics; scheduled retraining jobs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Data privacy compliance; robust drift thresholds.

- Hybrid byte–subword pipelines

- Sector: research, on-device AI

- What: Combine byte-level models (e.g., ByT5, MEGABYTE) with Unigram for higher-level structure in multilingual settings; explore FSP for compression at higher tiers.

- Tools/Workflows: Multiscale tokenization stacks; curriculum training from bytes to subwords.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Architectural changes; careful throughput/quality tradeoff validation.

- Language revitalization and low-resource support

- Sector: cultural heritage, NGOs, academia

- What: Use robust Unigram defaults to train viable tokenizers on smaller corpora; leverage morphology-friendly segmentation for languages with complex morphology.

- Tools/Workflows: Community toolkits with pretoken-based seed init; lightweight training recipes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of even small curated corpora; local expertise for evaluation.

- Regulatory guidance for energy-efficient and equitable tokenization

- Sector: policy/energy, regulators

- What: Recommend simplified training settings and equity audits (e.g., MorphScore reporting) in AI procurement and compliance frameworks.

- Tools/Workflows: Best-practice documents; audit templates; reporting requirements.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Evidence linking tokenizer choices to energy and equity outcomes; regulator engagement.

- Safety tooling for detecting anomalous or brittle tokens

- Sector: AI safety, platform integrity

- What: Build analyzers that flag low-frequency, unstable, or poorly segmented tokens; couple with improved seed init to reduce oddities.

- Tools/Workflows: “Token anomaly” scanners; integration with prompt-safety evaluations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: While the paper cites prior glitch-token work, direct causal mitigation via these methods needs validation; requires ongoing monitoring.

Notes on tradeoffs and feasibility across applications:

- The paper demonstrates a compression–objective–morphology tradeoff: FSP improves compression but slightly worsens Unigram loss and MorphScore. Application choices should be driven by task constraints (latency vs linguistic fidelity).

- Many expensive Unigram defaults (extra EM steps, digamma, early prune thresholds) can be safely simplified, but downstream task performance must still be verified.

- BPE may generalize slightly better out-of-domain; validate tokenizers on target distributions, especially for production and multilingual deployments.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.