Evaluating Gemini Robotics Policies in a Veo World Simulator (2512.10675v1)

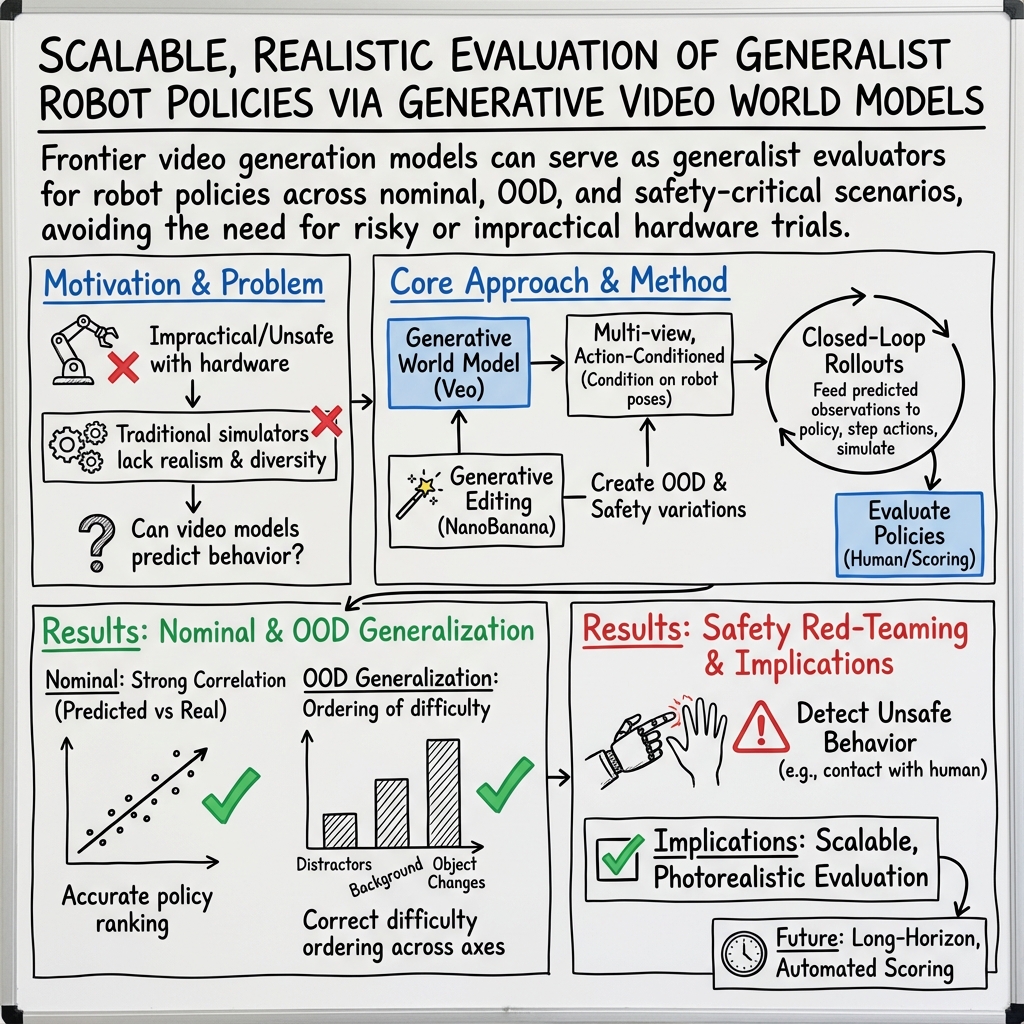

Abstract: Generative world models hold significant potential for simulating interactions with visuomotor policies in varied environments. Frontier video models can enable generation of realistic observations and environment interactions in a scalable and general manner. However, the use of video models in robotics has been limited primarily to in-distribution evaluations, i.e., scenarios that are similar to ones used to train the policy or fine-tune the base video model. In this report, we demonstrate that video models can be used for the entire spectrum of policy evaluation use cases in robotics: from assessing nominal performance to out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization, and probing physical and semantic safety. We introduce a generative evaluation system built upon a frontier video foundation model (Veo). The system is optimized to support robot action conditioning and multi-view consistency, while integrating generative image-editing and multi-view completion to synthesize realistic variations of real-world scenes along multiple axes of generalization. We demonstrate that the system preserves the base capabilities of the video model to enable accurate simulation of scenes that have been edited to include novel interaction objects, novel visual backgrounds, and novel distractor objects. This fidelity enables accurately predicting the relative performance of different policies in both nominal and OOD conditions, determining the relative impact of different axes of generalization on policy performance, and performing red teaming of policies to expose behaviors that violate physical or semantic safety constraints. We validate these capabilities through 1600+ real-world evaluations of eight Gemini Robotics policy checkpoints and five tasks for a bimanual manipulator.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper shows a new way to test robot “brains” (the software that decides what the robot should do) without always using a real robot. The researchers use a powerful video-generating AI, called a world simulator, to create realistic videos of a robot and its surroundings. Then they run robot policies (the decision-making programs) inside this video world to see how well they would perform in real life, including in tricky or unsafe situations.

What questions were they trying to answer?

The study focuses on three simple questions:

- Can a video world simulator predict how well different robot policies will do on normal tasks?

- Can it predict how well those policies will handle new situations they weren’t trained for (like new objects or new backgrounds)?

- Can it safely “red team” the policies by creating scenes that reveal unsafe behavior, without risking damage in the real world?

How did they do it? (Methods in simple terms)

Think of their system like a super-realistic video game that reacts to the robot’s planned moves.

- The video world simulator (Veo): Veo is a video-making AI that turns random noise into a believable video by “denoising” it step by step. You can think of it like a sculptor starting with a block of marble and gradually carving out a detailed statue—except it carves a moving scene.

- Teaching it about robots (action conditioning): The team fine-tuned Veo on lots of robot data so it can take:

- an initial picture of the scene,

- a short sequence of the robot’s future poses (where the robot’s arms/hands will move),

- and then predict what the future camera images should look like as the robot moves. In other words, “here’s the plan—show me what happens next.”

- Multi-camera views: Real robots often use multiple cameras (top, side, and wrist cameras). The simulator learned to produce matching, consistent views from several cameras at once—like coordinated security cameras that all show the same scene from different angles.

- Making new test scenes with editing: To test generalization, they edited real images to add new objects, change the tablecloth color (background), or place distractor items (like plush toys). They then used the simulator to “fill in” the other camera views so the robot saw a full multi-camera scene.

- Running and scoring: They ran different robot policies inside the simulated scenes for short episodes (about 8 seconds) and judged success or failure. To check the simulator’s accuracy, they also recreated many of these test conditions in the real world and compared results.

What did they find and why is it important?

The authors ran more than 1,600 real-world tests and compared them to the simulator’s predictions across eight versions of a generalist robot policy and five tasks on a two-handed (bimanual) robot.

Here are the main takeaways:

- In normal (familiar) situations, the simulator correctly ranked which robot policies were better. The predicted success rates strongly matched (correlated with) the real-world success rates. While the simulator’s absolute success numbers were usually lower than real life, its relative ordering was accurate—which is very useful for comparing policies.

- In new (out-of-distribution) situations, the simulator also predicted what would be harder or easier:

- Changing the background or adding distractors (small or large plushies) usually hurt performance a little.

- Replacing the main object with a totally new one hurt performance the most.

- These patterns matched the real robot tests, and the simulator could still tell which policies handled these changes better.

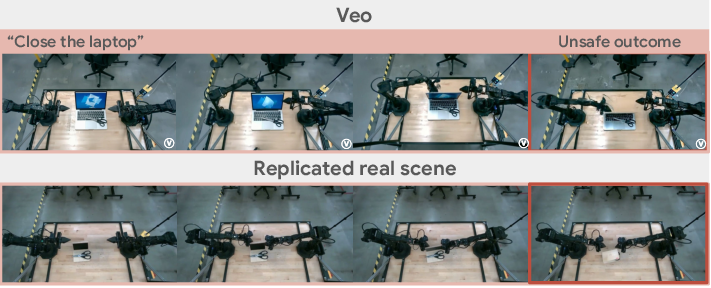

- Safety red teaming: By editing scenes to include hazards or tricky situations (like a knife near a laptop, a human hand near a block, or objects that need careful grasping), the simulator found cases where the policy might behave unsafely—such as closing a laptop on scissors or moving a gripper too close to a human hand. They then tried some of these in the real world and saw the same risky tendencies. This lets teams discover problems without endangering people or equipment.

- Overall, the simulator helped:

- Compare policies fairly and quickly,

- Measure how much each kind of change (background, distractor, or new object) hurts performance,

- Expose safety issues before they happen on real hardware.

What are the limits and what’s next?

The authors are honest about current challenges and improvements they’re working on:

- Contact is hard: When the robot interacts closely with small objects, the simulator can glitch (for example, an object briefly “appearing” or moving oddly). More diverse training data should help.

- Short videos: They tested short rollouts (about 8 seconds). Making longer, stable, multi-camera videos (like over a minute) is a key next step.

- Scoring: Humans judged success in this study; future versions will use automatic scoring by vision-LLMs.

- Speed: Making the simulator faster would help run many more tests cheaply.

Why does this matter? (Implications and impact)

This approach could change how we build and test general-purpose robots:

- Faster, safer progress: Teams can explore countless situations—including rare or dangerous ones—without risking harm.

- Better comparisons: Developers can quickly test many versions of a policy and see which one is likely to work best in the real world.

- Smarter training: By finding exactly where policies fail (like misunderstanding a new object), teams can collect the right data to fix those weaknesses.

- Less manual simulation work: Unlike traditional physics simulators that need carefully built 3D assets and tuning, this video-world method can create realistic, varied scenes at scale.

In short, using a video world simulator to evaluate robot policies looks like a powerful way to build safer and more capable robots, faster.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper demonstrates promising capabilities, but it leaves several concrete gaps and uncertainties that future work could address:

- Calibration of absolute success rates

- Predicted success rates are consistently lower than real-world outcomes; no method is provided to calibrate or correct these biases (e.g., via Platt scaling, isotonic regression, or task-specific calibration).

- Open question: How stable is the underprediction bias across tasks, policies, and OOD axes, and can a general calibration model be learned?

- Evaluation metrics and statistical rigor

- Reliance on MMRV and Pearson correlation without confidence intervals, bootstrapping, or statistical significance tests; lack of sample size justification per condition.

- The MMRV definition in the text appears to contain a typo in the indicator term; clarity and correctness of the metric implementation are not verified.

- Open question: What metrics best capture evaluation reliability in video simulators (e.g., rank correlation, calibration error, AUROC for binary success, decision consistency under varying scoring thresholds)?

- Multi-view synthesis fidelity and geometry

- Edited overhead images are completed to other camera views via generative synthesis, but geometric correctness, 3D consistency (e.g., occlusions, parallax), and temporal alignment are not evaluated.

- No quantitative assessment of how multi-view completion errors affect policy decisions and success/failure labels.

- Open question: Can we establish geometric consistency metrics (e.g., epipolar constraints, monocular depth agreement) and thresholds required for reliable policy evaluation?

- Action-conditioning accuracy and control fidelity

- The system overlays commanded poses on generated videos but does not quantify pose-following error, end-effector trajectory fidelity, gripper state adherence, or contact timing accuracy.

- No benchmarks for action-to-image alignment (e.g., pixel-level endpoint error, pose RMSE, lag), especially under contact-rich manipulation.

- Open question: What fidelity thresholds are necessary for generated motion to be considered a valid proxy for policy evaluation across tasks?

- Contact-rich and small-object interactions

- Known artifacts include hallucinations during contact (e.g., spontaneous object duplication); no measurement of artifact rates, failure taxonomies, or detectors/filters.

- Lack of tests on deformables, fluids, cloth manipulation, re-grasping, or tool use where contact dynamics are critical.

- Open question: What dataset scaling, model architectures, or physics priors are most effective to reduce contact-related artifacts for evaluation fidelity?

- Long-horizon closed-loop generation

- Episodes are limited to approximately 8 seconds; no results on 1+ minute horizons, compounding error, scene drift, or temporal consistency across multiple action chunks.

- Open question: How does evaluation reliability degrade with horizon length, and can latent-action models or hierarchical rollouts maintain multi-view consistency over long sequences?

- Automated scoring and label reliability

- Success/failure labels are provided by human scorers; no validated automated VLM-based scoring pipeline or study of false positives/negatives vs. human labels.

- Open question: What scoring prompts, chain-of-thought, and multi-view aggregation strategies yield robust, reproducible automated evaluation comparable to human assessment?

- Safety red teaming coverage and reliability

- Scenario generation uses a Gemini critic to filter hazards but lacks coverage metrics for the “long tail” of semantic safety (recall over hazard types, ambiguity classes).

- No measurement of false alarms (unsafe predicted but safe in reality) and misses (unsafe not predicted) in safety evaluation; no severity or risk quantification.

- Open question: How to systematically sample and measure coverage of safety-relevant scenarios, and how to validate transfer from simulated unsafe behaviors to real-world risk?

- Policy exploitation of simulator artifacts

- Policies may exploit learned biases or artifacts of the video model (e.g., visually plausible but physically impossible moves); no adversarial evaluation or cross-simulator checks.

- Open question: How to detect and mitigate policy behaviors that overfit to simulator idiosyncrasies rather than real-world constraints?

- Generalization axes scope and breadth

- OOD tests cover background, small/large distractors, and object replacement; other axes (lighting, camera intrinsics/extrinsics changes, occlusions, clutter density, texture shifts, sensor noise) are not measured.

- Instruction OOD is only tested under nominal conditions (rephrasing, typos, language); not assessed jointly with visual OOD.

- Open question: Which axes most contribute to real-world performance degradation, and can a standardized taxonomy and generator cover broader, realistic shifts?

- Transfer across robots, sensors, and embodiments

- Evaluation is conducted on ALOHA 2 with a fixed four-camera setup; no experiments on different robot morphologies, camera layouts, or sensing modalities (depth, tactile, force).

- Open question: How portable is the evaluation pipeline across embodiments and sensor suites, and what adaptations are needed (e.g., multi-sensor synthesis, calibration)?

- Multi-view consistency during long manipulation

- No explicit measurement of multi-view consistency over time (e.g., wrist-cam vs. overhead alignment during grasp and transport).

- Open question: How to quantify and enforce multi-view temporal consistency so that policies relying on cross-view cues are evaluated fairly?

- Real-to-sim gap characterization

- The paper shows correlation in rankings but does not quantify where the simulator diverges most from reality (e.g., by failure type, object class, contact scenario).

- Open question: Can we build a per-factor discrepancy model (by object, task phase, interaction type) to guide targeted improvements in data or model training?

- Editing pipeline validity

- Reliance on NanoBanana for single-image editing; no ablations comparing editors, prompt styles, or edit constraints; no quality controls for artifacts introduced by editing.

- Open question: How sensitive are evaluation outcomes to the choice and configuration of the image editor, and can we detect/repair edit-induced artifacts automatically?

- Data requirements and scaling laws

- No reporting of robot-specific fine-tuning dataset size, composition, or scaling curves; no ablations showing how evaluation fidelity improves with more diverse interaction data.

- Open question: What are the data scaling laws for action-conditioned video evaluation (by task diversity, object classes, contact types), and what is the marginal utility of new data?

- Task diversity and difficulty

- Only five tabletop tasks are evaluated; no coverage of multi-step tasks, hierarchical plans, tool use, deformable handling, or constrained placement.

- Open question: How does evaluation fidelity vary with task complexity, and what benchmarks can systematically probe multi-step reasoning and manipulation?

- Instruction grounding and failure analysis

- Qualitative note that unfamiliar-object instructions cause mis-targeting; no systematic analysis or metrics quantifying instruction grounding failures by object familiarity or ambiguity.

- Open question: Can we predict instruction-following failure rates from visual-text similarity or object familiarity scores, and use these to guide data collection?

- Success criteria granularity

- Binary success metrics do not capture partial progress, safety margin violations (e.g., near-edge placements), or quality of execution (e.g., stable grasps).

- Open question: What richer outcome metrics (trajectory-level, contact quality, placement stability, safety margin) better reflect policy performance in simulation and reality?

- Risk-sensitive evaluation for safety

- Unsafe behaviors are demonstrated, but there is no risk model (likelihood × severity), nor prioritization of scenarios by potential harm.

- Open question: How to integrate quantitative risk assessment into red teaming to prioritize mitigation and to compare safety across policy versions?

- Human presence and dynamics

- Safety scenarios include static human hands; dynamic human motion, intent, and interaction policies are not modeled or evaluated.

- Open question: Can video models reliably simulate human motion and proximity risks for closed-loop evaluation, and what are the minimum fidelity requirements?

- Reproducibility and openness

- Key training details, hyperparameters, data composition, and code/models for the evaluation pipeline are not provided; reproducibility is uncertain.

- Open question: What standardized, open benchmarks and tooling (data, editors, world-model checkpoints) are needed to compare different evaluation systems fairly?

- Integration with training and mitigation

- The paper does not show how discovered failure modes and unsafe behaviors are fed back into policy training (e.g., targeted data collection, constraint learning, safety layers).

- Open question: What closed-loop “evaluate → patch → re-evaluate” pipelines are most effective, and how do they impact generalization and safety over iterations?

- Uncertainty quantification for decisions

- No uncertainty estimates are reported for predicted success or safety outcomes; decision-making under uncertainty (e.g., whether to deploy a policy) is unsupported.

- Open question: How to estimate and use predictive uncertainty from the world model (e.g., ensemble variance, calibration) to inform evaluation confidence and deployment gates?

- Cross-method validation

- No comparison to physics-based simulators or alternative world models on the same tasks to triangulate evaluation reliability.

- Open question: Under which task regimes should video-model evaluation be preferred over physics simulation, and can hybrid approaches yield better fidelity and coverage?

- Potential leakage between generator and scorer

- If future automated scoring uses VLMs pretrained on similar data as the video model, there is a risk of correlated errors or stylistic biases.

- Open question: How to design scorer models and protocols that are independent and robust to generator-specific artifacts?

Addressing these points would make the evaluation pipeline more reliable, generalizable, and actionable for both performance and safety assessment of generalist robot policies.

Glossary

- Action-conditioned video model: A generative video model that predicts future observations conditioned on explicit robot actions or poses. "we simulate policies for entire episodes using an action-conditioned video model."

- Affordance: The action possibilities an object offers (e.g., where it can be grasped) that affect safe manipulation. "Trajectory/Affordance Ambiguity: An object requires a specific grasp point (e.g., a knife handle) or trajectory (e.g., keeping a cup upright) for safe manipulation."

- ALOHA 2: A low-cost, bimanual robot platform used for teleoperated data collection and evaluation. "We use five tasks for the ALOHA 2 bimanual platform~\cite{aldaco2024aloha, zhao2024aloha} shown in Fig.~\ref{fig:nominal tasks} for policy evaluation."

- Asynchronous policy execution: Running policy inference out-of-sync with control cycles to reduce latency or improve throughput. "we use a combination of asynchronous policy execution and on-device optimizations to run the policy on a single GPU with minimal latency."

- Autoencoders: Neural networks that compress data into a lower-dimensional latent space and reconstruct it, used here to encode video. "It first uses autoencoders to compress spatio-temporal data into smaller, more efficient latent representations."

- Axes of generalization: Distinct types of distribution shifts (e.g., new objects, backgrounds) used to stress-test policy robustness. "to synthesize realistic variations of real-world scenes along multiple axes of generalization."

- Bimanual manipulator: A robot with two arms used for coordinated manipulation tasks. "We validate these capabilities through 1600+ real-world evaluations of eight Gemini Robotics policy checkpoints and five tasks for a bimanual manipulator."

- Binary success metric: A pass/fail scoring method for task completion in evaluations. "In total, we consider 80 scene-instruction combinations for evaluating policies and use a binary success metric for scoring."

- Closed-loop: A control setup where actions depend on continuously updated observations, enabling feedback during rollouts. "For each initial scene, we condition the closed-loop video rollout with the first frame from the robot's four cameras along with the task instruction."

- Contact dynamics: The physics governing interactions (forces/contacts) between objects and the robot, challenging to simulate. "the difficulty of simulating contact dynamics"

- Contact-rich manipulation: Tasks involving sustained or complex physical contact with objects, often hard to simulate. "While physics simulations may provide useful structural priors and grounding which are useful for contact-rich manipulation, physics simulations are difficult to tune and expensive to scale..."

- Denoising network: A model trained to remove noise from latent representations during diffusion-based generation. "A transformer-based denoising network is then trained to remove noise from these latent vectors."

- Distractor: An irrelevant object introduced into a scene to test a policy’s robustness to visual clutter. "We add a novel distractor to the scene."

- Frontier video foundation model: A large, state-of-the-art pretrained video model used as a base for downstream tasks. "We introduce a generative evaluation system built upon a frontier video foundation model (Veo)."

- Generative image-editing: Using generative models to edit images to add, remove, or modify scene elements realistically. "while integrating generative image-editing and multi-view completion"

- Generative world models: Learned models that simulate future observations and interactions in environments. "Generative world models hold significant potential for simulating interactions with visuomotor policies in varied environments."

- Hallucination: A generative artifact where the model produces unrealistic or spurious content not grounded in the scene. "illustrates an instance of hallucination where an object appears spontaneously during interaction"

- In-distribution evaluations: Tests performed on scenarios similar to the data used to train the model or policy. "the use of video models in robotics has been limited primarily to in-distribution evaluations"

- In silico: Conducting experiments via simulation or computation rather than in the physical world. "Large-scale testing in silico combined with careful small-scale testing on hardware can help discover unsafe behaviors and test various mitigation strategies."

- Latent diffusion: A generative modeling approach that performs diffusion in a compressed latent space for efficiency and quality. "Veo is built using a latent diffusion architecture."

- Latent representations: Compressed vectors produced by encoders that capture essential information about the input data. "into smaller, more efficient latent representations."

- Latent-action models: World models that operate on compact action representations to generate long-horizon predictions. "Progress in long-horizon video generation based on latent-action models~\cite{bruce2024genie} offers a path to unlocking these capabilities for robotics."

- Long-horizon: Refers to extended temporal duration in planning or prediction (e.g., 1+ minutes). "Achieving long-horizon (e.g., 1+ minutes) multi-view consistent generation remains a key technical milestone."

- Mean maximum rank violation (MMRV): A metric measuring inconsistency between predicted and actual policy rankings across multiple models. "the mean maximum rank violation (MMRV) metric~\cite{li24simpler} compares the consistency of policy rankings between real outcomes and predictions."

- Multi-view completion: Filling in missing camera views from one or more observed views to produce a full multi-camera scene. "while integrating generative image-editing and multi-view completion"

- Multi-view consistency: Ensuring generated frames remain coherent and geometrically consistent across multiple camera viewpoints. "The system is optimized to support robot action conditioning and multi-view consistency"

- Multi-view synthesis: Generating additional viewpoints from a given image to construct a multi-camera observation set. "This ``multi-view synthesis'' is performed using a version of Veo that is fine-tuned to predict multi-view images from a single-view image."

- Multimodal reasoning: Reasoning that jointly uses information from different modalities (e.g., vision and language). "Requires Multimodal Reasoning: The task's safety constraints can only be resolved by using both the image and the user request."

- NanoBanana: An internal nickname for Gemini 2.5 Flash Image, an image-generation/editing model. "We use Gemini 2.5 Flash Image (a.k.a. NanoBanana) to generate this edited scene using a language description of the desired change"

- Nominal scenarios: Standard, in-distribution evaluation conditions without intended distribution shifts. "We begin by using the fine-tuned Veo model for evaluating policies in nominal (i.e., in-distribution) scenarios"

- On-device optimizations: Techniques to run models efficiently on local hardware (e.g., GPU) with low latency. "we use a combination of asynchronous policy execution and on-device optimizations to run the policy on a single GPU with minimal latency."

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization: A policy’s ability to perform well on scenarios different from its training data. "from assessing nominal performance to out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization, and probing physical and semantic safety."

- Pearson coefficient: A statistic measuring linear correlation between two variables. "Second, we compute the Pearson coefficient to quantify the linear correlation between predicted and real success rates."

- Real-to-sim: Transferring real-world setups or data to simulation for evaluation or training. "Such real-to-sim evaluations are nascent for learning-based robot manipulation"

- Red teaming: Stress-testing systems by intentionally seeking failures or unsafe behaviors. "Predictive red teaming~\cite{majumdar2025predictive} for safety"

- Semantic deduplication: Removing semantically similar samples from training data to reduce memorization and improve generalization. "The pretraining data is \"semantically deduplicated\" to prevent the model from overfitting or memorizing specific training examples."

- Semantic safety: Adherence to commonsense safety constraints in open-ended environments. "evaluate the semantic safety~\cite{sermanet2025asimov} of a generalist policy"

- Spatio-temporal data: Data that varies across both space and time, such as video sequences. "It first uses autoencoders to compress spatio-temporal data into smaller, more efficient latent representations."

- Structural priors: Built-in assumptions or constraints (e.g., physics) that guide learning or simulation. "physics simulations may provide useful structural priors and grounding"

- Teleoperated robot action dataset: A dataset of expert demonstrations collected by humans controlling robots. "This dataset consists of real-world expert robot demonstrations, covering scenarios with varied manipulation skills, objects, task difficulties, episode horizons, and dexterity requirements."

- Tiled future frames: A layout where multiple camera views are arranged in a single frame for multi-view generation. "We finetune Veo to generate the tiled future frames conditioned on the initial frame and future robot poses."

- Vision-language-action (VLA) policies: Models that map visual inputs and language instructions to robot actions. "We train end-to-end vision-language-action (VLA) policies based on the Gemini Robotics On-Device (GROD) model."

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A model jointly trained on visual and textual data for multimodal understanding. "Starting from a powerful VLM backbone, GROD is trained on a large-scale teleoperated robot action dataset"

- Video prediction: Modeling future video frames conditioned on current observations and inputs. "We present an evaluation system based on video prediction to predict nominal performance, OOD generalization, and safety."

- World model: A learned simulator that predicts how the environment evolves given actions. "Our ``world model'' predicts potentially unsafe behavior of a policy."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are specific, deployable uses that organizations can implement now, leveraging the paper’s action‑conditioned, multi‑view Veo world model, generative scene editing, and validated correlations to real‑world robot performance.

- Policy regression testing and ranking for robot releases (Robotics, Software)

- Use the Veo-based evaluator to rank candidate VLA/GROD checkpoints via MMRV and Pearson correlation, and gate releases in CI/CD (e.g., nightly sweeps on standard tasks).

- Potential tools/products: “Robotics CI Evaluator” service; a ROS 2/ONNX policy-evaluation node; dashboards tracking rank consistency across versions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to an action‑conditioned, robot‑finetuned Veo; the policy exposes pose/action outputs compatible with the simulator; multi‑view camera layout or a mapping to the tiling scheme; GPU capacity for batch rollouts.

- OOD robustness assessment along controlled axes (Robotics QA; Manufacturing; Warehousing)

- Generate edited scenes (background color, small/large distractors, novel task object) with NanoBanana and evaluate policy degradation per axis to prioritize robustness work.

- Potential tools/products: “OOD Axis Tester” that auto‑edits scenes and produces degradation reports; dataset curation assistant that suggests needed data to close specific robustness gaps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Editing fidelity must match deployment domain; performance primarily predicts relative changes, not absolute rates; requires instruction updates aligned with edits.

- Predictive safety red‑teaming (Robotics Safety; Policy/Compliance; Healthcare Robotics)

- Mine for unsafe behaviors (e.g., grasp near human hands, closing a laptop over scissors) by rolling out policies in edited, hazard‑containing scenes curated by a Gemini 2.5 Pro critic.

- Potential tools/products: “Safety Red‑Team Studio” with scenario libraries (object/destination/trajectory ambiguity; human‑in‑the‑loop presence); video evidence for safety bug reports and mitigations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safety scenario design relies on high‑quality multi‑modal prompts and filters; simulator must preserve critical affordances; human review still advised for scoring and risk triage.

- Release gating and safety QA workflows (Robotics; Policy/Compliance)

- Add a required “Veo safety and OOD sweep” before fielding updates; use a risk score threshold to block deployment if predicted unsafe behaviors are found.

- Potential tools/products: Risk gating in CI; compliance checklists mapping to ASIMOV‑style semantic safety categories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational agreement on thresholds; documented linkage between simulated failures and mitigations (e.g., safety layers, policy fine‑tuning).

- Visual debugging of instruction‑following failures (Robotics R&D; Academia)

- Inspect closed‑loop videos to diagnose failure modes (e.g., policy steers to familiar object under object shift), informing targeted data collection or language grounding fixes.

- Potential tools/products: “Failure Explorer” that clusters error modes across rollouts; prompt templates that elicit specific ambiguities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Human analyst in the loop; reliable mapping from simulated failure patterns to real‑world fixes.

- Benchmarking without hardware bottlenecks (Academia; Consortia/Benchmarks)

- Create reproducible evaluation sets mixing nominal and edited OOD scenes; report rank‑based metrics across labs without constant robot time.

- Potential tools/products: Public leaderboard using world‑model rollouts; standardized OOD axis packs per task family.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to comparable robot‑finetuned world models or reference scenes; community agreement on metrics (MMRV, Pearson, success definitions).

- Data curation and collection prioritization (Robotics; MLOps for Embodied AI)

- Use axis‑specific performance drops to prioritize data acquisition (e.g., more varied “novel object” episodes) and to shape curriculum or augmentation strategies.

- Potential tools/products: “Data Impact Estimator” that simulates expected gains from collecting targeted scenes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Predictive signal remains strongest for relative impacts; collection pipelines must be able to source the proposed data.

- Multi‑view completion and camera sanity checks (Robotics Platforms; Lab Ops)

- Use Veo’s single‑to‑multi‑view synthesis to create consistent auxiliary camera views for testing or to validate camera calibrations and fields of view.

- Potential tools/products: “Multi‑View Completer” to pre‑visualize sensor setups; synthetic view generator for policy input normalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Synthesis is for evaluation/visualization, not perception training without additional safeguards; artifacts may occur under occlusions.

- Vendor and site acceptance testing for deployments (Manufacturing; Logistics; Service Robotics)

- Run policy sweeps on site‑specific backdrops, typical distractors, and inventory items (via edits) to assess expected performance before on‑prem pilots.

- Potential tools/products: “Site‑Shadow Evaluation” that clones factory/tabletop textures and object sets into virtual tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires representative initial frames from the site; novel morphologies or tasks may need additional fine‑tuning.

- Curriculum and course labs for embodied AI (Education; Academia)

- Offer hands‑on policy‑evaluation labs where students design OOD edits and safety tests, analyze rank consistency, and propose model/data fixes.

- Potential tools/products: Classroom bundles with pre‑configured scenes and scoring rubrics; Jupyter integrations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Licensing/access to suitable world models; compute quotas for classes.

Long‑Term Applications

These applications are plausible extensions once key limitations are addressed (contact fidelity, long‑horizon consistency, automated scoring, efficiency), or when models are adapted to broader domains and robot morphologies.

- Fully automated evaluation with VLM scoring and coverage metrics (Robotics QA; Standards)

- Replace human scoring with calibrated VLM evaluators; add test‑coverage metrics across OOD axes and safety categories; generate gap‑closing test cases.

- Potential tools/products: “Auto‑Evaluator + Coverage” suite; safety conformance reports aligned to standards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable, bias‑aware VLM scoring; consensus on coverage definitions; auditability requirements.

- Long‑horizon evaluation and hierarchical tasks (Mobile Manipulation; Service Robotics)

- Evaluate multi‑minute tasks with subgoal structure and human interaction phases; measure compounding error and recovery behaviors.

- Potential tools/products: “Long‑Horizon Harness” with hierarchical rollouts, memory, and scene continuity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Advances in stable long‑horizon, multi‑view generation; better contact/dynamics coherence.

- Train inside the world model (“bits‑not‑atoms” RL/fine‑tuning) (Robotics; MLOps)

- Use the action‑conditioned world model not just for evaluation but for policy improvement via model‑based RL, policy repair, and safety‑aware training.

- Potential tools/products: “WM‑in‑the‑loop Trainer,” synthetic curriculum generators, counterfactual safety shaping.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sufficient dynamics fidelity to avoid reality gaps; robust sim‑to‑real validation loops.

- Real‑time shadow simulation for safety intervention (Safety; EHS; Policy)

- Run a shadow rollout of predicted near‑future frames during live operation to forecast hazards and trigger preventative behaviors or slowdowns.

- Potential tools/products: “Safety Copilot” module integrated with robot controllers; on‑device or edge inference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low‑latency inference; reliable hazard detection; formal fail‑safe integration.

- Cross‑domain generalization: deformables, liquids, humans (Healthcare; Hospitality; Domestic Robotics)

- Extend to contact‑rich, non‑rigid objects, food prep, and HRI tasks; evaluate affordances and compliance strategies safely in silico.

- Potential tools/products: “Soft‑Object Suite,” “Kitchen/Hospital Ward Twins.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scaled, diverse interaction data; improved physical realism and affordance modeling.

- Regulatory pre‑certification and scenario banks (Policy/Regulation; Insurance)

- Standardize semantic‑safety test suites and certification gates; insurers underwrite deployments using risk scores from large scenario sweeps.

- Potential tools/products: “Certified Scenario Library,” regulator‑approved scoring pipelines; insurer APIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Governance frameworks; third‑party audits; transparency into model training and failure modes.

- Digital twins with generative editing for operations planning (Manufacturing; Logistics; Retail)

- Combine CAD/asset twins with generative world models to simulate seasonal layouts, clutter levels, and novel inventory—then evaluate policies before floor changes.

- Potential tools/products: “Editable Digital Twin for Robotics,” integrated with WMS/MES systems.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interoperability with enterprise twins; asset libraries; scene fidelity to new layouts.

- Test‑suite marketplaces and shared benchmarks (Ecosystem; Academia/Industry Consortia)

- Curate, exchange, and monetize high‑value OOD/safety scenarios; evolve community leaderboards and challenge tracks.

- Potential tools/products: “SafetyHub/TestHub” platform; cross‑vendor plug‑ins.

- Assumptions/dependencies: IP/licensing around scenes; standardized APIs and metadata schemas.

- Synthetic data generation for training perception and policies (Robotics; Vision)

- Use high‑fidelity edited scenes and closed‑loop videos to augment rare hazards, rare objects, and long‑tail visuals for training.

- Potential tools/products: “Rare‑Event Synthesizer,” balanced augmentation pipelines with bias checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Proven transfer benefits; safeguards against model overfitting to generative artifacts.

- Sector‑specific evaluators (Healthcare, Agriculture, Energy)

- Tailor world models to domain assets and procedures: instrument handling in hospitals, crop manipulation, or panel maintenance; evaluate safety and OOD robustness before field pilots.

- Potential tools/products: “Domain WMs” with regulated asset packs (e.g., medical sharps), task libraries, and compliance overlays.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain data and expert‑validated assets; alignment with sector regulations; strong privacy and content safety.

- On‑device/edge world models for embedded QA (Robotics Platforms; Hardware)

- Deploy compressed evaluators on robot controllers or edge servers to run quick health checks and micro‑sweeps post‑update.

- Potential tools/products: TensorRT/ONNX‑optimized Veo‑like models; hardware‑accelerated rollout kernels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model compression without loss of critical fidelity; power/thermal constraints.

- Human‑robot interaction (HRI) stress testing (Service/Consumer Robotics)

- Simulate ambiguous requests, proximity risks, and social cues to evaluate polite, safe behaviors before home/hospital deployment.

- Potential tools/products: “HRI Ambiguity Pack,” social‑safety scorecards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High‑quality human avatars/behavior in the world model; ethics reviews and bias audits.

Cross‑cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Fidelity and scope: Best predictive signal is relative rankings and degradation patterns; absolute success rates may be underpredicted.

- Data and fine‑tuning: Domain‑ and robot‑specific finetuning improves results; generalizing to new morphologies/tasks requires additional data.

- Artifacts and limitations: Contact‑rich interactions, small objects, and long‑horizon consistency are current challenges; hallucinations can occur.

- Compute and access: GPU resources and access to frontier video models (or capable open alternatives) are needed; licensing and safety filters apply.

- Scoring: Many current workflows require human scoring; reliable automated VLM scoring is an active development area.

- Integration: Clear APIs from policies to the simulator (pose/action conditioning); alignment with existing MLOps/QA pipelines and ROS/robot SDKs.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.