Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems (2512.08296v1)

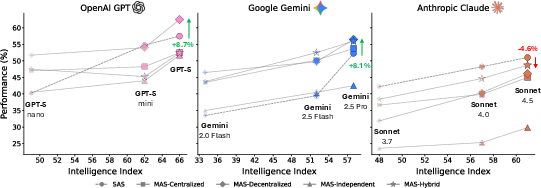

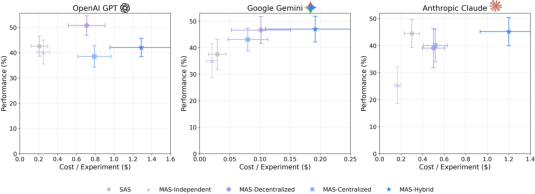

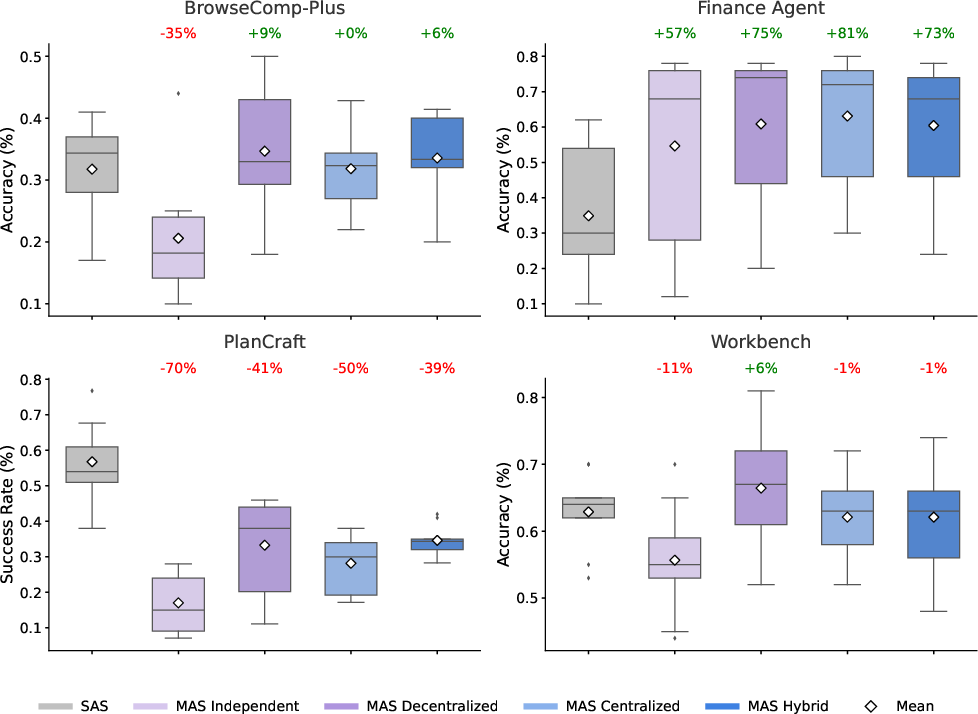

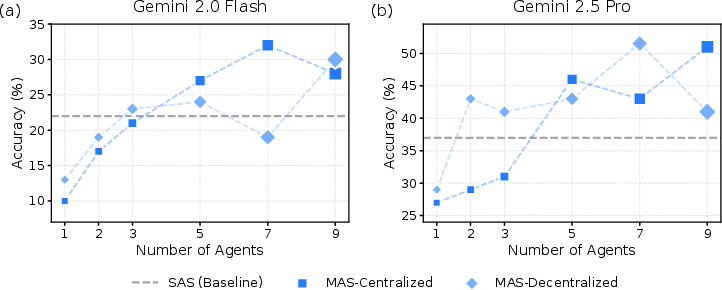

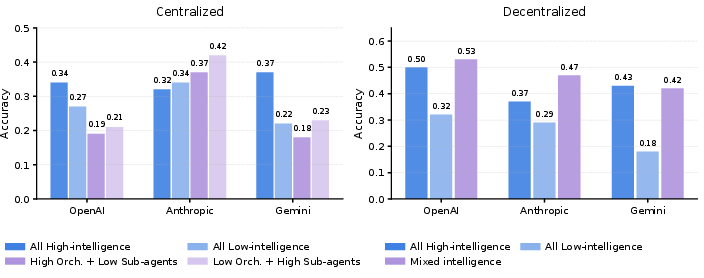

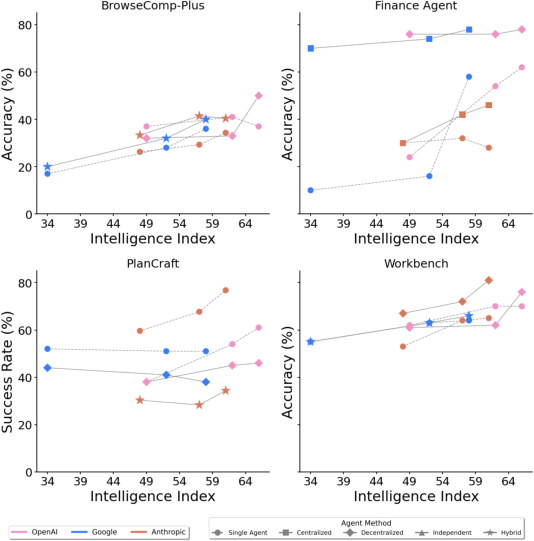

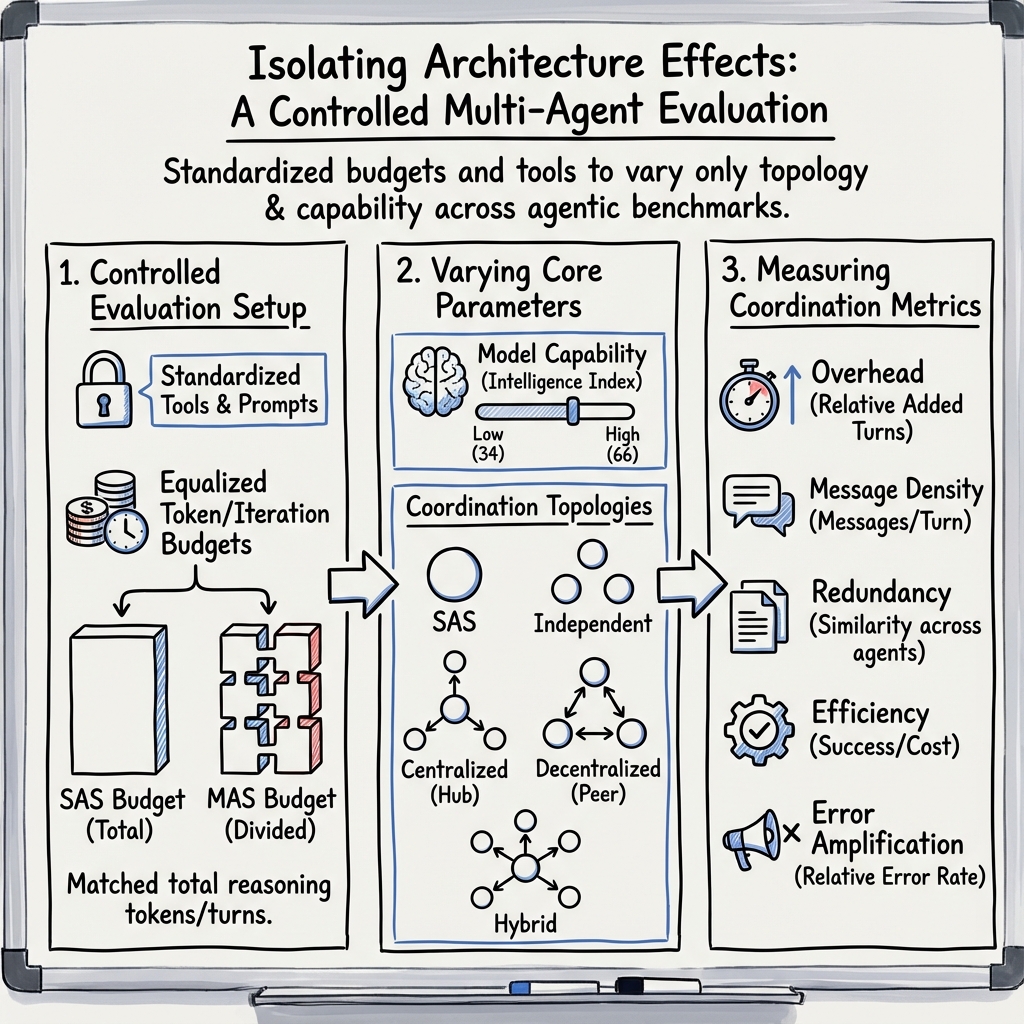

Abstract: Agents, LLM (LM)-based systems that are capable of reasoning, planning, and acting are becoming the dominant paradigm for real-world AI applications. Despite this widespread adoption, the principles that determine their performance remain underexplored, leaving practitioners to rely on heuristics rather than principled design choices. We address this gap by deriving quantitative scaling principles for agent systems. We evaluate this across four diverse benchmarks: Finance-Agent, BrowseComp-Plus, PlanCraft, and Workbench. Using five canonical architectures (Single, Independent, Centralized, Decentralized, Hybrid) instantiated across three LLM families, we perform a controlled evaluation spanning 180 configurations with standardized tools and token budgets. We derive a predictive model using empirical coordination metrics, including efficiency, overhead, error amplification, and redundancy, that achieves cross-validated R2=0.513. We identify three dominant effects: (1) a tool-coordination trade-off: under fixed computational budgets, tool-heavy tasks suffer disproportionately from multi-agent overhead. (2) a capability saturation: coordination yields diminishing or negative returns (beta=-0.408, p<0.001) once single-agent baselines exceed ~45%. (3) topology-dependent error amplification: independent agents amplify errors 17.2x through unchecked propagation, while centralized coordination contains this to 4.4x. Centralized coordination improves performance by 80.9% on parallelizable tasks like financial reasoning, while decentralized coordination excels on dynamic web navigation (+9.2% vs. +0.2%). Yet for sequential reasoning tasks, all multi-agent variants degraded performance by 39-70%. The framework predicts the optimal coordination strategy for 87% of held-out configurations, providing a predictive principle of agentic scaling based on measurable task properties.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper studies how to build teams of AI “agents” so they work well in the real world. An agent here is an AI powered by a LLM that can think step-by-step, use tools, and take actions (like browsing the web or running code). Many people assume that using more agents together will always beat a single strong agent. The authors show that isn’t true. They discover simple, measurable rules that tell you when adding more agents helps—and when it actually hurts.

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on three big, plain-English questions:

- What makes an agent system perform well or badly? Is it the number of agents, how they’re organized, how smart the model is, or the type of task?

- When does having agents collaborate help, and when does it slow things down or spread mistakes?

- Can we build a simple, predictive rule that picks the best agent setup for a new task based on task features, without trial and error?

How did they do the paper?

Think of this like testing different team designs in a school project:

- Single-Agent System (SAS): One very capable student does all the work alone.

- Multi-Agent Systems (MAS): A team with different ways of working together:

- Independent: Everyone works separately; at the end, they combine answers. Little talking, just merging.

- Centralized: There’s a “team lead” who assigns tasks and checks everyone’s work before submitting.

- Decentralized: Everyone talks to everyone (group discussion) to reach a shared answer.

- Hybrid: A team lead plus some peer-to-peer chatting.

They tested these five setups on four kinds of real tasks:

- Finance-Agent: Analyzing financial data and making reasoned conclusions.

- BrowseComp-Plus: Finding and combining information across the web.

- PlanCraft: Planning actions step-by-step in a game-like, changing world.

- Workbench: Doing realistic work tasks that involve picking and using the right tools.

To be fair, they kept important things the same across all tests:

- Same tools (like web search or code execution) and prompts.

- Same “token budget” (think: how much text the AI is allowed to read and write).

- Different LLMs from three families and multiple capability levels (like stronger or weaker students), tested across 180 setups.

They didn’t just look at final accuracy. They also measured:

- Coordination overhead: how much “talking” or organizing time the team needs.

- Efficiency: success per unit of effort.

- Error amplification: how much mistakes spread or get corrected.

- Redundancy: how similar the agents’ answers are (useful for voting or cross-checking).

Finally, they built a predictive model (like a simple formula) using these measurements. It explained about half of the performance differences and correctly chose the best architecture in most cases.

What did they find and why it matters?

Here are the most important, easy-to-grasp takeaways:

- Tool–coordination trade-off: If a task needs lots of tool use (like many apps, websites, or code runs), splitting work across multiple agents often hurts performance under fixed budgets. Why? Each agent gets fewer “thinking tokens,” and time spent coordinating steals effort from actually using tools well.

- Capability saturation: If a single agent already does pretty well (around 45% success or more in their tests), adding more agents often makes things worse. The extra coordination cost outweighs the small improvement you might get from collaboration.

- Error amplification depends on team structure:

- Independent teams can accidentally multiply mistakes (about 17×), because nobody checks each other before merging.

- Centralized teams (with a strong coordinator) contain mistakes much better (about 4×) because the “lead” reviews and filters work.

- Task type matters more than team size:

- Parallel-friendly tasks (like analyzing different parts of a company’s finances and then merging): Centralized teams did much better (up to about +81% over a single agent).

- Dynamic web browsing (where exploring different pages at once helps): Decentralized teams had modest gains (about +9%).

- Strictly step-by-step tasks (like careful planning where each step depends on the last): All multi-agent setups got worse (about −39% to −70%) because too much coordination fragments the reasoning and adds overhead.

- Predictive rule of thumb: Their model correctly picked the best agent setup for about 87% of new, unseen task configurations. That means you can often choose the right architecture by looking at task properties (Can it be split up? How tool-heavy is it? How sequential is it?) instead of guessing.

Simple analogies for key ideas

- Team chatter vs. getting work done: If the team spends too much time talking, they don’t get enough time to work, especially when the task already needs a lot of hands-on tool use.

- Group projects vs. recipes: Group projects with parts you can split among teammates benefit from collaboration. But following a recipe step-by-step is better done by one focused cook; handing off steps among many cooks slows things down and causes mistakes.

- Teacher as coordinator: A good coordinator can catch and reduce errors early. Without one, wrong ideas spread and become the final answer.

Implications and impact

This research helps anyone building AI systems choose smarter designs:

- Don’t assume “more agents is better.” Match the team design to the task.

- Use a centralized coordinator for tasks that split naturally into parts (finance analysis, report writing with sections).

- Prefer decentralized discussion for open-ended exploration (like web research).

- Stick to a single strong agent for tightly sequential tasks (careful planning, step-dependent procedures).

- Expect tool-heavy tasks to suffer if you spread limited compute across many agents; consider giving one agent more budget instead.

Big picture: The paper moves AI agent design from guesswork to measurable, predictable rules. That can save time and money, reduce errors, and make AI systems more reliable in real-world applications.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, intended to guide actionable future research:

- External validity beyond the four chosen benchmarks: how do the reported scaling principles transfer to other agentic settings (e.g., embodied robotics, multi-modal perception/action, long-horizon scientific workflows, enterprise RPA, or safety-critical domains)?

- Team-size scaling is not characterized: results are reported for small teams (3–4 agents; coordination complexity C ∈ [0.35, 1.8]); it remains unknown how performance, overhead, and error amplification scale with larger n or with varying orchestrator/debate rounds (r, d, p).

- Generality of the “~45% single-agent baseline” capability saturation threshold: is this breakpoint consistent across tasks and models, or does it vary with domain characteristics, model families, or budget regimes?

- Budget sensitivity: conclusions are derived under fixed token/iteration budgets; it is unclear how findings change under different computation budgets (e.g., higher budgets, latency constraints, or cost ceilings) and whether the tool-coordination trade-off persists when budgets are relaxed or optimized per architecture.

- Missing comparison to strong single-agent baselines that use ensemble-style sampling (e.g., self-consistency, multiple CoT samples) under the same budget; this is critical to distinguish coordination gains from simple compute-based ensembling.

- Homogeneous vs. heterogeneous teams: agents appear largely homogeneous; the impact of specialization (skills, tools, memory, prompts) or heterogeneity on coordination efficiency and error control is not explored.

- Orchestration policy choices are under-specified: aggregation methods (e.g., majority vote vs. weighted synthesis vs. verifier gates), override rules, and termination criteria may materially affect outcomes; their independent contributions are not ablated.

- Communication protocol design is fixed to natural language messages; the effect of structured schemas, compressed summaries, learned protocols, or programmatic constraints on overhead and information loss is not evaluated.

- Memory architecture is held constant; the role of richer shared memory, retrieval-augmented communication, learned long-term memory, or cross-agent memory synchronization in mitigating context fragmentation is not assessed.

- Context-window effects are not disentangled: how do larger context windows or better selective recall alter the SAS–MAS trade-off and the observed coordination tax?

- Tool ecosystem representativeness and fidelity: while tools are “controlled,” the robustness of conclusions under realistic tool latencies, failures, non-determinism, and API variability (including rate limits) is not tested.

- Operationalization of task properties (e.g., decomposability, search entropy, tool complexity) lacks explicit, reproducible definitions and measurement procedures; automatic, dataset-agnostic quantification remains an open need.

- Stability and reproducibility: dynamic benchmarks like web browsing can change over time; the paper does not detail environment versioning/snapshots, seed control, or sensitivity to stochasticity (agent sampling, tool nondeterminism).

- Predictive model transparency and robustness: the mixed-effects model (R² ≈ 0.51; leave-one-domain-out R² ≈ 0.89) is trained on four domains; risk of overfitting with few domains, model calibration on genuinely new tasks, uncertainty intervals, and error analysis are not reported.

- Metric sensitivity and validity: proxies such as contradiction via BERTScore, redundancy via embedding similarity, and error amplification as a ratio to SAS may be unstable; sensitivity analyses to thresholds/embeddings and absolute error rates are missing.

- Lack of ablations isolating core mechanisms: the paper attributes effects to overhead, fragmentation, and validation bottlenecks, but does not present targeted ablations (e.g., message compression, memory sharing on/off, verifier insertion/removal) to causally validate mechanisms.

- No exploration of learning-based coordination: all systems appear prompt-based; whether fine-tuning, RL, or meta-learning can reduce coordination tax and error propagation remains unexplored.

- Cross-lingual, multi-modal, and domain-shift generalization: experiments focus on predominantly text tasks in English; performance under multilingual settings, vision-conditioned tasks, and distribution shifts is untested.

- Latency and reliability trade-offs: although tokens/turns are normalized, wall-clock latency, tail latencies, and reliability under API outages/errors are not quantified—key concerns for deployment.

- Safety and risk: there is no analysis of adversarial robustness, prompt injection in web tasks, or risk-aware orchestration in safety-critical workflows.

- Human-in-the-loop settings are not considered: how human oversight or corrective interventions interact with coordination topologies and budgets is an open question.

- Tool-routing policies are fixed; adaptive tool selection, learned tool routing, or tool-sharing strategies across agents are not evaluated as potential mitigations for the tool-coordination trade-off.

- Interaction depth and long-horizon behavior: the dependence of coordination benefits on trajectory length and state drift (e.g., error recovery after long chains) is not systematically analyzed.

- Cross-family normalization via an “Intelligence Index” obscures underlying capability differences; how robust the findings are to alternative capability normalization schemes is unclear.

- Fairness of budget allocation: per-architecture equalization via iterations/tokens may disadvantage architectures that rely on longer messages or more turns; alternative budget schemes (e.g., equal wall-time or dollar cost) are not tested.

- Release and reproducibility: code, prompts, message traces, and tools are not reported as publicly released, limiting independent validation and extension.

- Boundary conditions for MAS degradation: while sequential tasks degrade under MAS, guidelines for identifying “how sequential is too sequential” (e.g., thresholds on interdependence or tool-dependency) are not operationalized for practitioners.

- Interaction with self-reflection and verifier models: the relative efficacy of internal self-critique (SAS) vs. orchestrator-as-verifier (MAS) is not directly compared with matched costs.

- Applicability to dynamic team formation: the framework does not evaluate adaptive agent counts/topologies per instance (architectural search at inference time) and how this interacts with the predictive model.

Glossary

- Agentic Benchmark Checklist (ABC): A framework for evaluating whether tasks truly require agent-like interaction and adaptation. "Expanding from the Agentic Benchmark Checklist (ABC) introduced in \citep{zhu2025establishing}, we characterize agentic tasks as those requiring:"

- Agentic tasks: Tasks that benefit significantly from adaptive, multi-step interaction with an environment under uncertainty. "we characterize agentic tasks as those requiring: (i) sustained multi-step interactions with an external environment, (ii) iterative information gathering under partial observability, and (iii) adaptive strategy refinement based on environmental feedback."

- Architecture-dependent error cascades: Failure patterns where specific system architectures propagate and compound errors through coordination. "dominant inhibitory mechanisms, specifically the tool-coordination trade-off () and architecture-dependent error cascades, establishing fundamental limits on coordination effectiveness."

- BERTScore: A similarity metric for text based on contextual embeddings, used to assess semantic overlap or contradiction. "BERTScore similarity "

- Blackboard systems: Classical AI coordination method where agents communicate via a shared structured memory, not natural language. "Classical coordination mechanisms (e.g., blackboard systems) assume structured message formats rather than natural language, limiting their direct applicability to LLM-based agents."

- Capability ceiling: A threshold beyond which adding coordination yields diminishing or negative returns given strong single-agent performance. "Second, a capability ceiling (, ): tasks where single-agent performance already exceeds 45\% accuracy experience negative returns from additional agents"

- Capability saturation: The phenomenon where coordination no longer improves and may harm performance as base capability increases. "(2) a capability saturation: we observe that coordination yields diminishing or negative returns (, ) once single-agent baselines exceed an empirical threshold of ."

- Chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning: Prompting technique where models generate step-by-step reasoning traces before answers. "chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning \citep{wei2022emergent}"

- Cohen's kappa: A statistic measuring inter-rater agreement correcting for chance. "Cohen's : Finance Agent , Workbench , PlanCraft , BrowseComp-Plus ;"

- Coefficient of variation (CV): A normalized measure of dispersion (standard deviation divided by mean). "coefficient of variation "

- Collaborative scaling: How performance changes as collaboration increases, distinct from neural parameter scaling. "collaborative scaling exhibits logistic growth patterns emerging at substantially smaller scales"

- Communication topology: The structure defining who communicates with whom in a multi-agent system. "Communication topology defines information flow patterns between agents:"

- Consensus formation: The process by which agents reach agreement through interaction. "This enables consensus formation through peer-to-peer discussion."

- Coordination complexity: A quantified measure of the cost of coordinating multiple agents. "Coordination complexity is parameterized as "

- Coordination efficiency: Success normalized by coordination cost, capturing effectiveness per unit interaction. "Coordination efficiency $E_c = S/(T/T_{\text{SAS})$ (success normalized by relative turn count):"

- Coordination overhead: Extra computational and interaction cost incurred by coordinating agents. "Coordination overhead $O = (T_{\text{MAS} - T_{\text{SAS})/T_{\text{SAS} \times 100\%$: captures computational cost, identified as a primary bottleneck in production multi-agent deployments."

- Coordination tax: The inherent performance and cost penalty due to lossy communication and synchronization between agents. "they incur an unavoidable coordination tax in which the global context must be compressed into inter-agent messages."

- Debate rounds: Iterative peer-to-peer exchanges used by agents to argue and refine solutions. "Agents communicate in sequential debate rounds ()."

- Decentralized coordination: A peer-to-peer approach where agents communicate directly without a central controller. "decentralized coordination excels on dynamic web navigation ( vs. )."

- Decomposability: The extent to which a task can be split into parallelizable or independent subtasks. "task structure (e.g., decomposability, tool complexity, sequential dependencies)"

- Ensemble effects: Performance gains from aggregating multiple independent outputs without interaction. "On non-agentic benchmarks, multi-agent systems show monotonic improvement through ensemble effects (89\% on HumanEval with five agents)"

- Ensemble-style reasoning: Using multiple independent agents or runs and synthesizing their outputs. "suitable for ensemble-style reasoning."

- Error amplification: The degree to which errors increase under coordination relative to a baseline. "Error amplification $A_e = E_{\text{MAS}/E_{\text{SAS}$ (relative failure probability): directly tests whether MAS corrects or propagates errors."

- Error propagation: The process by which mistakes carry forward and compound through interaction chains. "error propagation dynamics dominate."

- Hybrid (MAS topology): A coordination structure combining central orchestration with selective peer-to-peer links. "Hybrid combines orchestrator control with directed peer communication."

- Independent (MAS topology): A configuration where agents do not communicate and outputs are only aggregated at the end. "Independent isolates the effect of parallelism (ensemble) without communication."

- Information gain: A measure of reduced uncertainty after coordination relative to before. "information gain from pre- vs.\ post-coordination uncertainty proxies"

- Intelligence Index: A composite capability score used to compare model strengths across families. "increasing model Intelligence Index (see Appendix \ref{sec:appendix-intelligence-index})"

- Leave-one-domain-out cross-validation: A validation method where models are trained on all but one domain and tested on the held-out domain. "leave-one-domain-out cross-validation achieves "

- Majority voting: An aggregation method where the most common output among agents is selected. "how sub-agent outputs are aggregated (e.g., majority voting, weighted synthesis)"

- Message density: The number of inter-agent messages per reasoning step, indicating communication intensity. "Message density (inter-agent messages per reasoning turn): quantifies communication intensity, a key factor in coordination scaling."

- Mixed-effects model: A statistical model incorporating fixed and random effects to explain performance variance. "We derive a mixed-effects model () using empirical coordination metrics"

- Multi-Agent System (MAS): A system with multiple LLM-backed agents that interact within an environment and possibly each other. "A Multi-Agent System is an agent system with "

- Neural scaling laws: Empirical relationships describing how model performance scales with size or data under training. "distinguishing collaborative scaling from neural scaling laws."

- Orchestration policy: The control logic governing coordination, aggregation, and termination among agents. "a communication topology , and an orchestration policy ."

- Orchestrator: A central controller agent that coordinates sub-agents’ activities and aggregates their outputs. "A single orchestrator coordinates rounds across sub-agents"

- Parametric knowledge: Knowledge encoded in model parameters rather than acquired through interaction or tools. "Controlled for Parametric Knowledge: within each model family, evaluation emphasizes adaptive reasoning over memorized facts."

- Partial observability: A condition where agents lack full access to the environment state and must gather information. "iterative information gathering under partial observability"

- Peer-to-peer: Direct agent-to-agent communication without centralized control. "Decentralized introduces peer-to-peer information fusion without hierarchy."

- Redundancy rate: A metric quantifying similarity among agents’ outputs, indicating duplication vs. diversity. "Redundancy rate (mean cosine similarity of agent output embeddings):"

- Self-reflection: Mechanisms where an agent evaluates and revises its own reasoning. "self-reflection \citep{shinn2023reflexion}"

- Sequential constraint satisfaction: Tasks requiring ordered steps where later actions depend on earlier ones meeting constraints. "tasks requiring sequential constraint satisfaction (planning: to )"

- Sequential Interdependence: A property where actions must be based on prior observations for success. "Sequential Interdependence: Later actions depend on earlier observations; a one-shot policy cannot achieve high reward."

- Single-Agent System (SAS): A system where a single LLM agent performs all reasoning, planning, and acting. "A Single-Agent System contains one reasoning locus ( where is the agent set)."

- Token budgets: Constraints on the number of tokens available for prompts, messages, and reasoning. "standardizing tools, prompt structures, and token budgets to isolate architectural effects from implementation confounds."

- Tool-coordination trade-off: The negative interaction between heavy tool use and coordination overhead under fixed budgets. "a tool-coordination trade-off: under fixed computational budgets, tool-heavy tasks suffer disproportionately from multi-agent overhead."

- Topology-dependent error amplification: Error growth that varies by communication/coordination structure. "topology-dependent error amplification: independent agents amplify errors through unchecked propagation, while centralized coordination contains this to ."

- Validation bottlenecks: Central checks that intercept and reduce errors before they propagate. "centralized coordination achieves 4.4-fold containment via validation bottlenecks, where the orchestrator reviews sub-agent outputs before aggregation."

- Variance inflation factor (VIF): A diagnostic measuring multicollinearity among predictors in regression. "Variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis confirmed no severe multicollinearity among retained predictors (all VIF )."

- Weighted synthesis: Aggregation where agent outputs are combined with weights reflecting confidence or quality. "how sub-agent outputs are aggregated (e.g., majority voting, weighted synthesis)"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable applications that leverage the paper’s findings and methods. Each item notes sector alignment and key assumptions or dependencies affecting feasibility.

- Architecture selection assistant for agent workflows

- Sector: software (agent platforms, MLOps)

- Application: A “MAS vs SAS decision wizard” that recommends coordination topology (single-agent, centralized, decentralized, hybrid) and team size from measured task properties (decomposability, tool complexity, sequential dependencies) and coordination metrics (efficiency, overhead, error amplification, redundancy).

- Tools/products/workflows: Plugins for LangChain, AutoGen, OpenAI Assistants, Vertex AI Agents; CI checks that gate MAS use when single-agent baselines exceed ~45% accuracy (capability saturation).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to per-task baselines; telemetry to compute efficiency and error amplification; matched token budgets; comparable tool APIs across architectures.

- Cost-governance dashboard for agent deployments

- Sector: software, finance (cost control), enterprise IT

- Application: Live dashboards tracking success per 1,000 tokens, message density, coordination overhead, and error amplification to identify when multi-agent overhead outweighs benefits (tool-coordination trade-off).

- Tools/products/workflows: Observability hooks in agent frameworks; budget fragmentation alerts when per-agent tokens fall below tool orchestration needs; automatic throttling of debate rounds or peer messages.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable token accounting; standardized logging of inter-agent messages; organization-wide cost policies.

- Centralized “AI Analyst Desk” for structured financial reasoning

- Sector: finance

- Application: A hub-and-spoke team with an orchestrator that assigns specialized sub-analysts (e.g., revenue, costs, market comps) and validates outputs before synthesis—matching the paper’s +80.9% gains on parallelizable finance tasks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Connectors to spreadsheets, databases, and SEC filings; orchestrator validation bottlenecks to limit error propagation (containment from 17.2× to ~4.4×).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Tasks decompose cleanly; domain validators for factuality; fixed computational budgets that preserve per-agent tool capacity.

- Decentralized multi-tab research assistant for dynamic web navigation

- Sector: information services, marketing, competitive intelligence

- Application: Multiple browser agents explore diverse pages in parallel and reach consensus via limited debate rounds; suitable for high-entropy search spaces (+9.2% on BrowseComp-Plus).

- Tools/products/workflows: Headless browser tools, scraping pipelines, peer message throttling; aggregator synthesis at the end.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Pages change rapidly (partial observability); debate depth kept shallow to avoid overhead; legal/ethical scraping policies.

- Agent gating in IDEs for software engineering tasks

- Sector: software development

- Application: Default to single-agent with tools for sequential debugging and repository navigation; selectively add a centralized “reviewer” as a validation bottleneck if needed, avoiding independent MAS which degrades sequential tasks (−39% to −70%).

- Tools/products/workflows: IDE extensions (Cursor, Copilot Workspace), test harness integration, orchestrated PR review agents.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Tool-heavy workflows (code execution, tests) amplify MAS overhead; enforce gating when SAS > ~45% accuracy.

- Workflow orchestration patterns for business tasks

- Sector: enterprise productivity

- Application: Apply centralized or hybrid topologies sparingly—use orchestrator validation for parallelizable subtasks (light data collection), keep sequential decisions within a single agent to minimize coordination tax (consistent with Workbench’s marginal MAS gains).

- Tools/products/workflows: Task routers that classify subtasks as parallelizable or sequential; per-subtask architecture selection; audit trail of decisions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate subtask classification; uniform tool interfaces; human oversight for critical steps.

- Agentic QA and benchmarking playbook

- Sector: academia, enterprise R&D

- Application: Adopt controlled evaluation templates (identical prompts/tools/token budgets) and the Agentic Benchmark Checklist to avoid confounds and misestimation; report coordination metrics (efficiency, redundancy, error amplification) alongside accuracy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Experiment harnesses with leave-one-domain-out validation; standardized success per token reporting.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Comparable LLM families; access to task-level validators; reproducible settings.

- Validation-bottleneck pattern library

- Sector: software, robotics, healthcare (non-diagnostic operations)

- Application: Introduce orchestrator checkpoints that verify sub-agent outputs before aggregation to limit error cascades, especially in safety-sensitive or compliance-heavy processes.

- Tools/products/workflows: Schema-based output contracts, domain validators, graded confidence thresholds that trigger re-analysis.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable validators; latency budgets permit validation rounds.

- Competitive intelligence and content curation teams

- Sector: marketing, media

- Application: Decentralized agents perform parallel content discovery across platforms; a central synthesizer produces reports with source attribution and contradiction detection (redundancy measurement).

- Tools/products/workflows: Social/API connectors, contradiction flags using embedding dissimilarity thresholds, synthesis templates.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust de-duplication; rate-limits and API compliance; calibrated contradiction thresholds.

- Procurement and compliance checklists for agentic systems

- Sector: policy, public sector, enterprise governance

- Application: Require vendors to disclose coordination metrics, token budgets, architecture topology, and gating rules (e.g., when SAS baselines exceed ~45%) to ensure cost and risk transparency.

- Tools/products/workflows: RFP templates referencing coordination overhead and error amplification; internal review gates for MAS claims.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Organizational mandate; metric literacy among reviewers; verifiable logs.

- Personal research and planning assistants

- Sector: daily life

- Application: Use decentralized agents to explore options (e.g., travel deals, product comparisons) and a central synthesizer for final recommendations; keep sequential tasks (itinerary building) inside a single agent to reduce fragmentation.

- Tools/products/workflows: Browser integrations, budget trackers, itinerary compilers.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Data quality from sites; careful partitioning of parallel vs sequential steps; privacy controls.

- Token budget and tool orchestration policies

- Sector: software operations

- Application: Automate per-agent token allocation to prevent budget fragmentation in tool-heavy tasks; trigger SAS mode or reduce team size when tools per task exceed thresholds (reflecting the tool-coordination trade-off).

- Tools/products/workflows: Budget allocators, per-agent token minimums, alerts when message density spikes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate accounting; known tool complexity; enforceable limits in orchestration layer.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications require further research, scaling, or ecosystem development before broad deployment.

- Auto-tuning orchestration engines with closed-loop routing

- Sector: software, robotics

- Application: Engines that adapt topology (SAS ↔ MAS, centralized ↔ decentralized), debate depth, and team size in real time from live metrics (efficiency, overhead, amplification), learning policies via reinforcement learning or Bayesian optimization.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust online estimation; safe exploration policies; standardized telemetry across tools.

- Industry standards for coordination metrics and reporting

- Sector: policy, standards (e.g., NIST, ISO)

- Application: Formalize measures like coordination efficiency (Ec), error amplification (Ae), redundancy, and message density; require vendors to publish these in evaluations and audits.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consensus among stakeholders; reference implementations; sector-specific validators.

- Agent architecture compilers

- Sector: software engineering

- Application: Compilers that translate task specifications and tool schemas into executable agent graphs (topology, roles, validators), guided by the paper’s selection rules (e.g., avoid MAS on sequential constraint satisfaction).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Rich task ontologies; mature tool descriptors; static and dynamic analysis of decomposability.

- Adaptive token/memory allocation across agents

- Sector: software

- Application: Systems that dynamically reallocate context, memory, and tokens to agents that need more tool orchestration capacity, reducing coordination tax in tool-heavy environments.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Long-context models; efficient memory sharing; latency budgets.

- Sector-specific orchestrators with guardrails

- Sector: healthcare, finance, legal

- Application: Centralized orchestration designs with strong validation bottlenecks and domain-specific checks; e.g., clinical documentation assistance (non-diagnostic), risk analysis, compliance reviews.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulatory clearance; high-quality validators; strict auditability and data governance.

- Safe multi-agent robotics controllers

- Sector: robotics, manufacturing

- Application: Hierarchical controllers where central validation contains error propagation; avoid independent MAS for sequential manipulation tasks; use decentralized exploration only for parallel perception tasks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Real-time guarantees; certified safety cases; multimodal tool interfaces.

- Tool ecosystem co-design to reduce coordination overhead

- Sector: software platforms

- Application: Tool APIs that return richer, structured feedback to minimize lossy inter-agent messaging; aggregators that compress global context for MAS use.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Vendor cooperation; schema standardization; backward compatibility.

- Education: collaborative tutoring systems

- Sector: education

- Application: Tutors that use decentralized exploration for diverse resources, then central synthesis; keep sequential learning plans within single-agent loops to avoid fragmentation of learner context.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Pedagogical validation; content provenance; student privacy protections.

- Synthetic task generators for architecture calibration

- Sector: academia, R&D

- Application: Benchmarks that parameterize decomposability, tool complexity, and interaction depth to stress-test architecture selection models and improve cross-domain generalization (beyond the paper’s four benchmarks).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Realistic simulators; measure invariance across LLM families; community datasets.

- Cross-vendor, model-agnostic orchestration layers

- Sector: software platforms

- Application: Abstractions that maintain consistent coordination metrics and selection rules across OpenAI, Google, Anthropics, and open-source models, improving portability and resilience to model changes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable capability indices; adapter layers; legal/API access.

Notes on Applicability and Generalization

- The paper’s predictive framework achieved cross-validated R2 = 0.513 and 87% accuracy in selecting optimal architectures on held-out configurations, with strong leave-one-domain-out performance (R2 = 0.89). This supports using measured task properties (not dataset-specific tuning) for architecture selection.

- Key rules-of-thumb are task-contingent:

- Prefer centralized coordination for parallelizable tasks (e.g., finance analysis).

- Prefer decentralized coordination for dynamic web navigation (high-entropy exploration).

- Avoid multi-agent variants on sequential constraint satisfaction; use single-agent with tools and optional validation bottlenecks.

- Gate MAS when single-agent baseline exceeds ~45% accuracy (capability saturation).

- Watch for tool-coordination trade-off under fixed budgets; tool-heavy workflows often favor SAS or very light centralization.

- Dependencies that impact feasibility include: high-quality tool APIs, domain validators, reliable telemetry, token budget discipline, consistent prompts across agents, privacy/compliance constraints, and stable access to LLM families with comparable capabilities.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.