Semantic Soft Bootstrapping: Long Context Reasoning in LLMs without Reinforcement Learning (2512.05105v1)

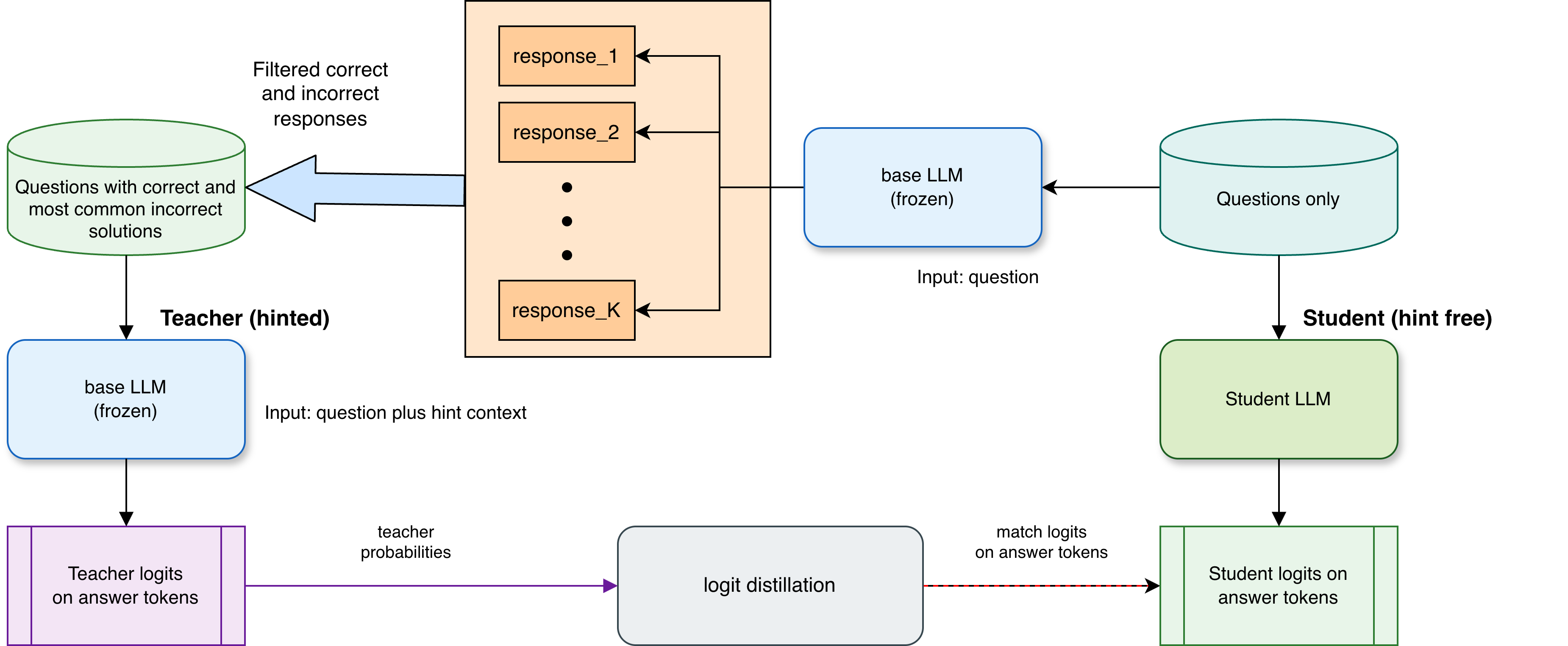

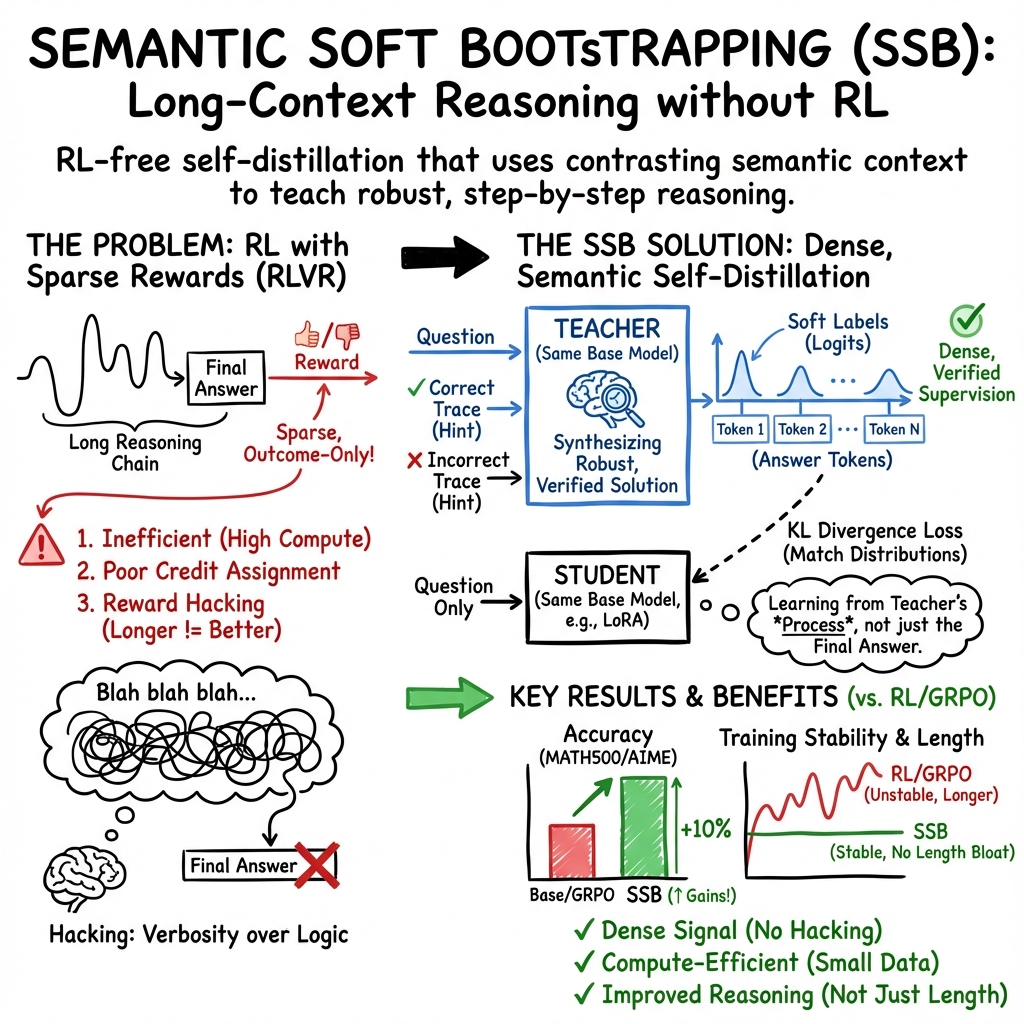

Abstract: Long context reasoning in LLMs has demonstrated enhancement of their cognitive capabilities via chain-of-thought (CoT) inference. Training such models is usually done via reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR) in reasoning based problems, like math and programming. However, RLVR is limited by several bottlenecks, such as, lack of dense reward, and inadequate sample efficiency. As a result, it requires significant compute resources in post-training phase. To overcome these limitations, in this work, we propose \textbf{Semantic Soft Bootstrapping (SSB)}, a self-distillation technique, in which the same base LLM plays the role of both teacher and student, but receives different semantic contexts about the correctness of its outcome at training time. The model is first prompted with a math problem and several rollouts are generated. From them, the correct and most common incorrect response are filtered, and then provided to the model in context to produce a more robust, step-by-step explanation with a verified final answer. This pipeline automatically curates a paired teacher-student training set from raw problem-answer data, without any human intervention. This generation process also produces a sequence of logits, which is what the student model tries to match in the training phase just from the bare question alone. In our experiment, Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct on GSM8K dataset via parameter-efficient fine-tuning. We then tested its accuracy on MATH500, and AIME2024 benchmarks. Our experiments show a jump of 10.6%, and 10% improvements in accuracy, respectively, over group relative policy optimization (GRPO), which is a commonly used RLVR algorithm. Our code is available at https://github.com/purbeshmitra/semantic-soft-bootstrapping, and the model, curated dataset is available at https://huggingface.co/purbeshmitra/semantic-soft-bootstrapping.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a new way to help LLMs think through tough problems, like math, using clear step-by-step reasoning, without relying on reinforcement learning. The method is called Semantic Soft Bootstrapping (SSB). It teaches a model to solve problems from just the question by letting the model learn from its own “hinted” solutions.

What are the main questions?

The researchers wanted to know:

- Can we improve an LLM’s step-by-step reasoning without using reinforcement learning (which can be slow, hard to set up, and sometimes unreliable)?

- Can a model teach itself better ways to reason by comparing a correct solution and a common mistake, then learning from that contrast?

- Will this approach be more efficient and still beat popular reinforcement learning methods on math benchmarks?

How did they do it? (Method)

The idea behind SSB is simple: make the model be both the teacher and the student—just with different information. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Generate multiple attempts for each question

Think of “rollouts” as the model trying a problem several times. For each math question, the model writes several solution attempts. The researchers collect:

- At least one correct solution (with the final answer written in a special

\boxed{...}format). - The most common incorrect answer (a mistake many attempts shared).

Step 2: Pick one good answer and one common mistake

From these attempts:

- They choose one correct step-by-step solution.

- They pick one wrong solution that contains the most frequent wrong final answer. This represents a typical misunderstanding.

Step 3: Let the model act as its own teacher

Now the model is given:

- The original question,

- The correct solution attempt, and

- The incorrect solution attempt.

It is asked to write a single, clear, careful solution that:

- Explains the steps,

- Warns about potential mistakes (like the one shown), and

- Ends with the correct final answer in

\boxed{...}.

This “teacher” solution is checked automatically to ensure the final answer is correct.

Step 4: Train a student to learn from soft signals

The model is then trained as a “student,” but this time it only sees the original question (no hints and no example solutions). The training goal is to make the student’s answer resemble the teacher’s answer.

To do this, they use:

- Logits: These are like the model’s “confidence scores” for the next word it might write. Instead of training on the exact words only (hard labels), the student matches the teacher’s confidence scores (soft labels) on the answer part.

- KL divergence: Think of this as a way to gently adjust the student’s preferences to align with the teacher’s, without forcing it to copy every word. It helps the student learn the teacher’s style of reasoning in a flexible way.

Key details:

- They used a small open model (Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct) and fine-tuned it efficiently using LoRA, which is like adding lightweight “training adapters” to a model instead of changing everything.

- They built a dataset of 256 paired teacher–student examples from GSM8K (a math question set), created by processing 950 questions.

- No reinforcement learning, no reward models, and no human annotations were needed.

What did they find?

The trained SSB model did better than a popular reinforcement learning method called GRPO on two math tests:

- MATH500:

- GRPO: 44.8% pass@1

- SSB: 55.4% pass@1

- Improvement: +10.6 percentage points

- AIME2024:

- GRPO: 3.33% pass@1

- SSB: 13.33% pass@1

- Improvement: +10 percentage points

Other observations:

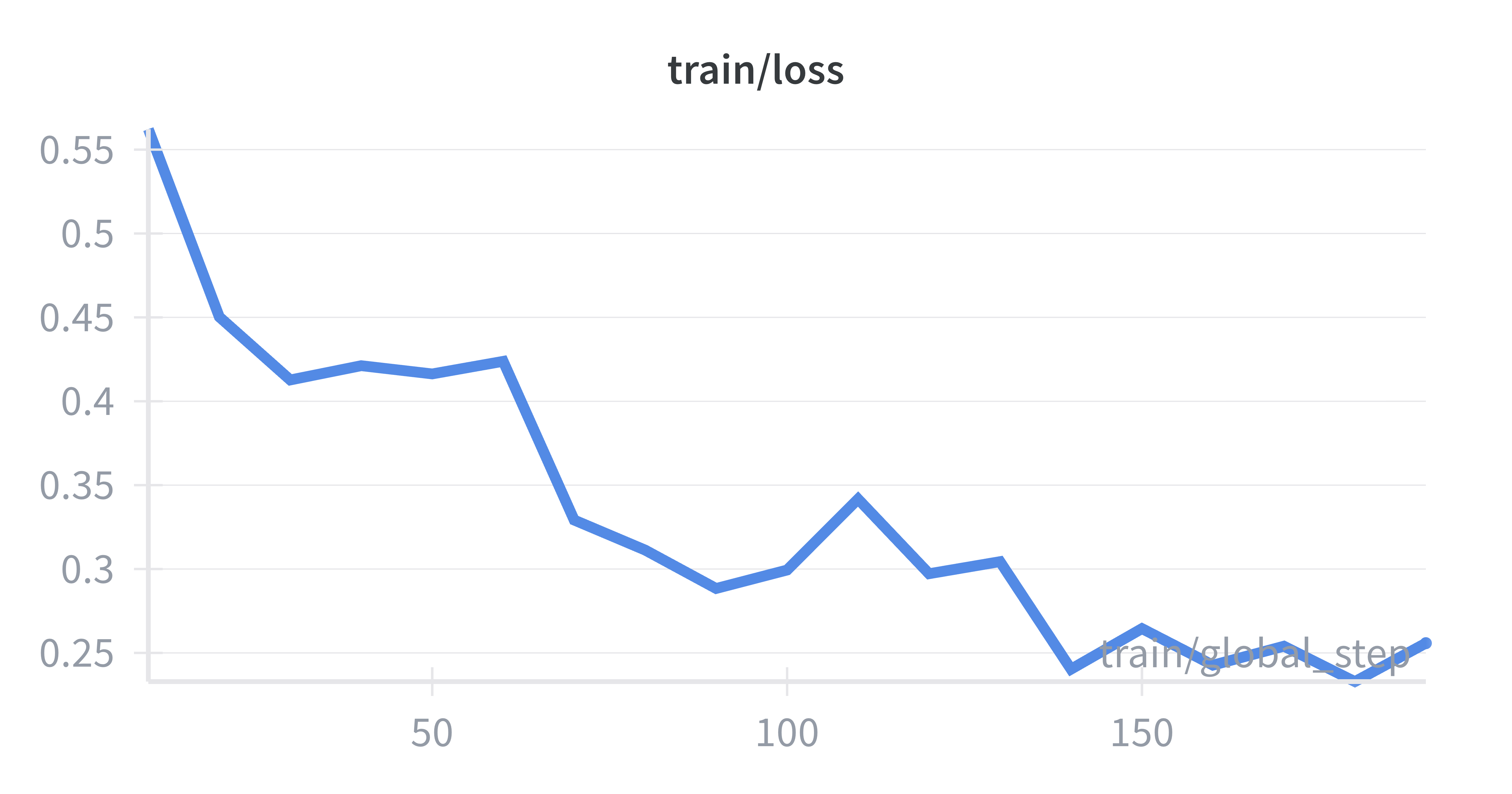

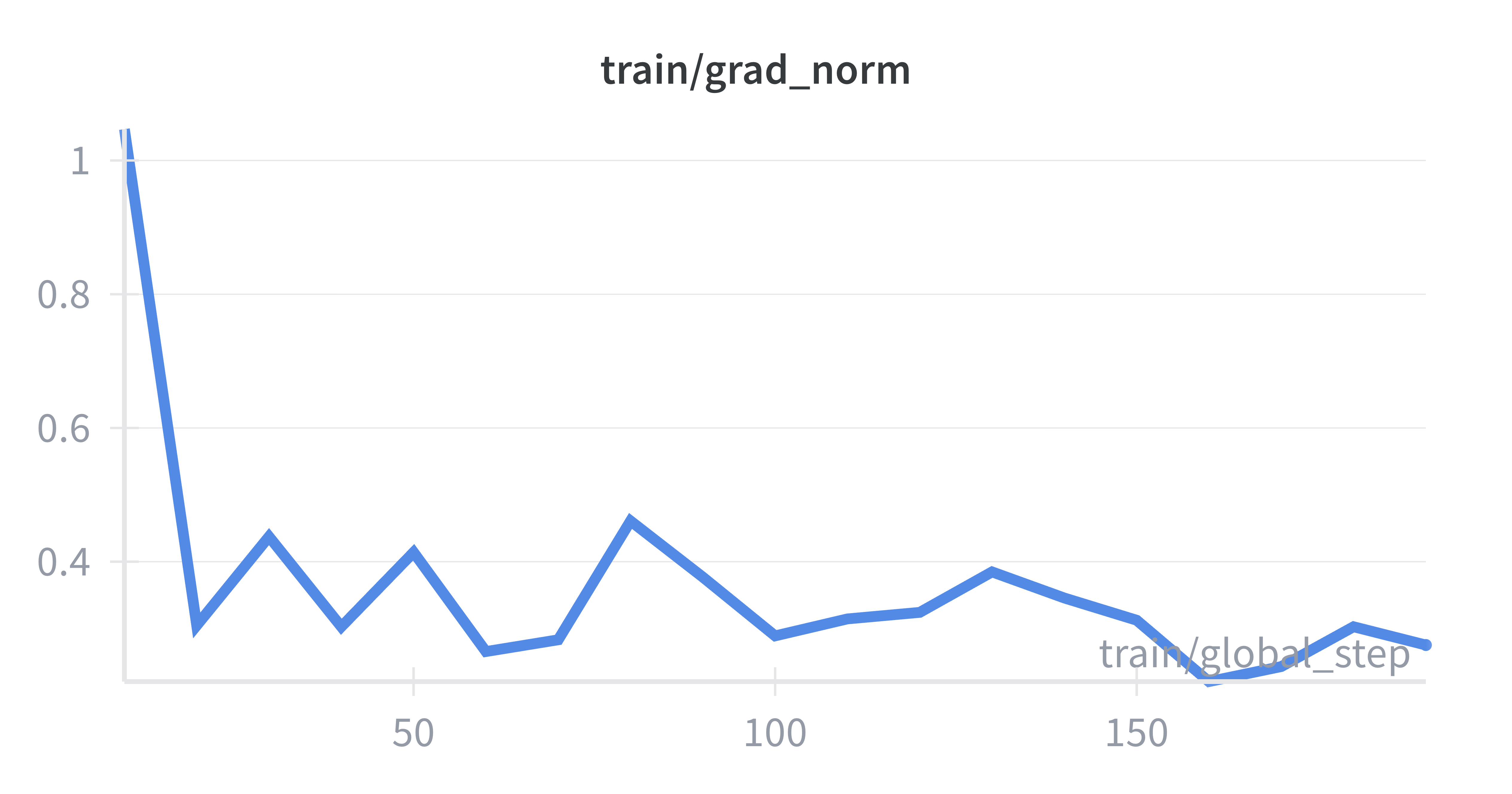

- Training was stable and fast, done on a single NVIDIA A100 40 GB GPU.

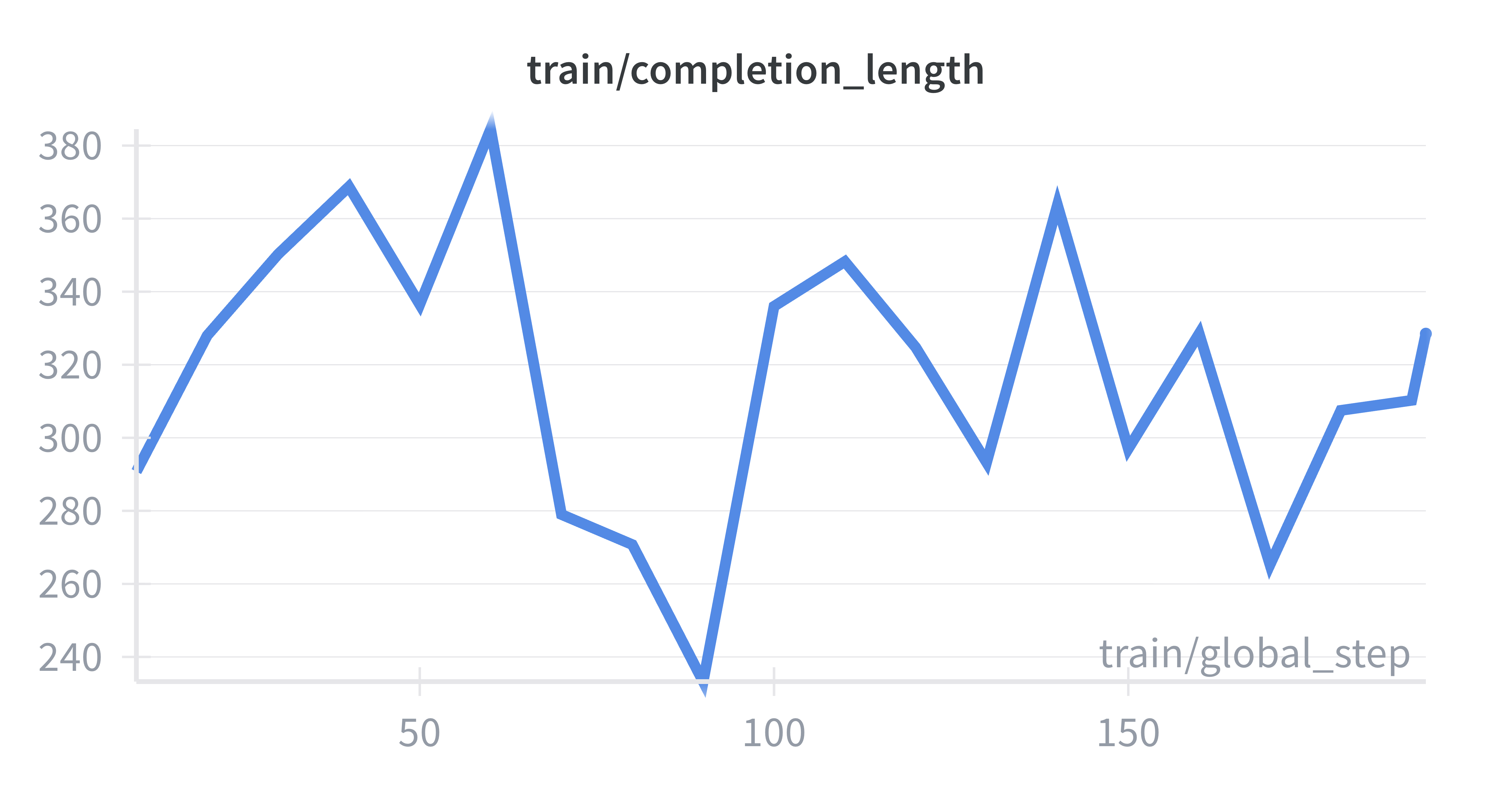

- The model’s responses did not become longer just to look “more thoughtful.” This suggests better reasoning doesn’t require longer answers or more tokens.

- SSB avoids common issues in reinforcement learning, like sparse rewards and “reward hacking,” because it learns from verified correct trajectories using soft guidance rather than blunt scores.

Why is this important?

- It shows that LLMs can improve their reasoning skills without complex reinforcement learning setups.

- It uses the model’s own mistakes and successes to create strong learning signals, automatically and at low cost.

- It’s efficient: small curated data, simple training, and good results.

- It encourages careful, step-by-step thinking and correct final answers, which are vital in math and programming.

Implications and potential impact

- This approach could scale to bigger models and more topics (like programming or science), helping them solve problems more reliably with less compute.

- It bridges the gap between “exploration” (trying different solutions) and “learning from signals” (like soft logits), combining good parts of both worlds.

- It could make future LLM training cheaper, faster, and safer by reducing the need for complex reward systems and manual labeling.

In short, Semantic Soft Bootstrapping is a practical, clever way for a model to learn from itself and become a better problem solver—without the heavy machinery of reinforcement learning.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of unresolved issues and concrete open questions that future work could address:

- Scalability across model sizes: SSB is only demonstrated on a 3B parameter model with LoRA. How do gains scale with larger backbones (7B–70B+) and full fine-tuning versus PEFT?

- Sample efficiency and scaling laws: No systematic paper of how accuracy scales with the number of curated pairs, rollouts per problem (), or training steps. What are the empirical scaling laws for SSB with respect to data, compute, and parameters?

- Fair compute comparison: The GRPO baseline uses 2000 GSM8K examples while SSB uses 256 curated pairs; GPU-hours, tokens processed, and rollout counts are not reported. What is the true compute–accuracy trade-off versus strong RLVR and non-RL baselines under matched budgets?

- Statistical robustness: Results are reported for a single run with no confidence intervals or seed variance. How stable are outcomes across random seeds, data subsamples, and hyperparameter sweeps?

- Generalization beyond math: SSB is evaluated only on math (MATH500, AIME2024). Does it transfer to program synthesis (with executability checks), scientific QA, multi-hop QA, tool-use, and multilingual settings?

- Long-context claims vs evidence: Despite the stated focus on “long context reasoning,” experiments do not vary or stress-test context length. Does SSB improve robustness in very long inputs (e.g., 32k–1M tokens) and under “lost-in-the-middle” conditions?

- Dependence on verifiable final answers: The method hinges on parsing a strict

\boxed{}answer for correctness. How can SSB be adapted to tasks without verifiable scalar answers, multiple valid outputs, or soft/graded correctness? - Formatting fragility: Strict

\boxed{}parsing may discard correct solutions due to formatting. How sensitive is performance to parser failures, alternative formats, or answer extraction noise? - Selection bias in data curation: Training examples are kept only when both a correct and an incorrect rollout exist. How does this filtering skew difficulty, error types, or topic coverage, and how does it affect downstream generalization?

- Teacher reasoning faithfulness: Teacher outputs are accepted if the final answer matches, but step-by-step reasoning may still contain errors or spurious steps. How often does SSB distill flawed rationales that coincidentally lead to correct answers?

- Distilling only answer tokens: The method matches logits on the “answer portion” only. What is the effect of also distilling the rationale tokens, or selectively supervising key reasoning steps?

- Negative example selection: SSB uses the most common wrong answer as a single negative. Would using multiple diverse negatives, adversarial negatives, or curriculum over error types improve robustness?

- Hyperparameter sensitivity: No ablations on rollout temperature (), distillation temperature (), LoRA rank, or number of rollouts . Which settings drive the observed gains and where are failure regimes?

- Direction of divergence and loss design: Only forward KL with temperature is used. How do reverse KL, JS divergence, mixed CE+KL, or confidence calibration (e.g., label smoothing) affect stability and performance?

- Offline vs iterative bootstrapping: SSB performs a single offline teacher generation pass. Would iterative rounds of regenerate–distill (with updated students acting as teachers) yield further gains or amplify bias?

- Process-level evaluation: Only pass@1 is reported. Do SSB-trained models exhibit higher stepwise correctness, fewer algebraic slips, better error correction, or improved calibration? Are CoT traces objectively higher quality?

- Diversity and mode collapse: Pass@k, entropy, and diversity of generations are not measured. Does SSB preserve or reduce solution diversity compared to RLVR or CoT-SFT methods?

- Robustness to misleading/contextual negatives: What happens if the included “incorrect” rollout is persuasive but wrong, partially correct, or adversarially constructed? Can SSB be hardened against such cases?

- Storage and I/O scaling: Precomputing and storing full teacher logits for each answer token may become a bottleneck at scale. What compression or on-the-fly strategies maintain performance with manageable storage and bandwidth?

- Inference efficiency: While completion length is reported stable, end-to-end latency, tokens-to-solution, and cost versus baselines are not measured. Does SSB improve accuracy per generated token?

- Catastrophic forgetting and breadth: Effects on non-math capabilities and general instruction following were not evaluated. Does SSB fine-tuning degrade other skills or safety behaviors?

- Baseline breadth: Comparisons exclude strong non-RL methods (e.g., STaR, Think–Prune–Train, BOLT, s1 test-time scaling, mixture-of-agents). How does SSB fare against these under controlled settings?

- Teacher–student identity: The teacher and student share the same base model. Would a stronger or different-architecture teacher help, or does same-model self-teaching suffice at larger scales?

- Error taxonomy and curriculum: The paper does not analyze which error types SSB reduces (arithmetic, algebraic, reasoning leaps). Can targeted curricula over error taxonomy accelerate learning?

- Domain shift and OOD robustness: No tests on harder, out-of-domain math (e.g., olympiad-level beyond AIME) or noisy/real-world problem statements. How robust is SSB under distribution shift?

- Safety and reward-hacking claim: The paper claims SSB eliminates reward hacking but provides no empirical stress tests. Under what conditions could the teacher exploit the acceptance criterion (e.g., spurious shortcuts) and how can this be detected?

- Contamination checks: Data leakage between GSM8K training and MATH500/AIME2024 evaluation is not ruled out. Can strict decontamination and audit ensure clean generalization claims?

- Reproducibility details: Exact seeds, rollout prompts, acceptance rates (yield from 950 to 256), and dataset release granularity are not fully documented. What is the reproducible pipeline to replicate results end-to-end?

- Multi-turn and tool-use extensions: It is unclear how to incorporate tools, verifiers, or external feedback in SSB. Can the hinted-context paradigm be adapted to tool-augmented reasoning and interactive multi-turn tasks?

- Theoretical grounding: Beyond intuition about KL “minimal shifts,” there is no formal analysis of when logit-level hint distillation should improve generalization or avoid self-training collapse. Can we provide theoretical guarantees or bounds?

Glossary

- AIME2024: A benchmark of challenging math problems used to evaluate reasoning models. "We then tested its accuracy on MATH500, and AIME2024 benchmarks."

- autoregressive LLM: A model that generates each token conditioned on previously generated tokens. "a pre-trained autoregressive LLM"

- bitter lesson: The idea that simple, scalable methods coupled with computation often outperform complex techniques. "the idea of bitter lesson"

- boxed final answer format: A strict output format requiring the final answer to be enclosed in LaTeX-style boxes for automatic checking. "using the boxed final answer format."

- chain-of-thought (CoT): Step-by-step natural language reasoning traces generated by a model. "via chain-of-thought (CoT) inference."

- contrastive learning: A learning paradigm that pulls together positive pairs and pushes apart negatives to shape representations. "in-context contrastive learning from negative pairs"

- cross-entropy loss: A standard loss for next-token prediction that maximizes likelihood of target tokens. "standard cross-entropy loss for next-token prediction"

- distribution shift: The mismatch between training and deployment data distributions that can degrade performance. "mitigates distribution shift between training and deployment."

- group relative policy optimization (GRPO): An RL algorithm that optimizes a policy using group-relative rewards; used in RLVR for reasoning. "group relative policy optimization (GRPO)"

- in-context learning: The ability of an LLM to adapt behavior based on provided examples or context at inference time. "in-context learning ability"

- inference-time framework: A method that improves outputs during inference without changing model weights. "is an inference-time framework"

- KL-based distillation loss: A knowledge distillation objective that matches student and teacher token distributions via KL divergence. "via a KL-based distillation loss,"

- KL divergence: A measure of how one probability distribution diverges from another, often used in distillation. "KL divergence quantifies the minimum shift"

- knowledge distillation: Training a student model to match a teacher model’s output distribution, often with softened targets. "is the classical formulation of knowledge distillation,"

- LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation; a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that injects low-rank adapters into model weights. "We use rank 32 LoRA"

- logit-level self-supervision: Supervising a student using the teacher’s precomputed logits rather than hard tokens. "all bootstrapping signal is provided through logit-level self-supervision"

- logits: The pre-softmax scores output by a model for each token, used to derive probabilities. "This generation process also produces a sequence of logits,"

- mixture-of-agents: A setup where multiple models/agents collaborate or provide diverse perspectives to improve performance. "mixture-of-agents"

- on-policy distillation: Distillation where the student learns from its own sampled outputs while the teacher provides targets. "On-policy distillation of LLMs"

- outcome-based reward formulation: An RL setup where rewards depend only on final outcomes, not intermediate steps. "in the outcome-based reward formulation,"

- parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT): Techniques that adapt a model by updating a small subset of parameters or adding adapters. "parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT)"

- pass@1: The probability that the model gets the correct answer in a single attempt. "pass@1 accuracy"

- pass@k: The probability that at least one of k sampled attempts is correct; often improved by RL methods. "boost pass@k"

- policy gradient: A class of RL methods that optimize policy parameters via gradients of expected rewards. "without any reward model or policy gradient."

- process supervision: Supervision that evaluates and guides intermediate reasoning steps rather than only final outcomes. "process supervision"

- rejection sampling: A procedure that discards samples failing a criterion, used here to enforce formatting. "performing a kind of rejection sampling for formatting."

- reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR): RL for reasoning tasks where correctness is objectively checkable, enabling reward assignment. "reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR)"

- reverse KL: The divergence D_KL(student || teacher), which encourages mode seeking; used as an alternative distillation objective. "alternative divergences such as reverse KL"

- rollouts: Stochastically sampled model outputs used to explore solution space and assess correctness. "several rollouts are generated."

- self-distillation: A training approach where a model serves as both teacher and student, learning from its own improved outputs. "a self-distillation technique,"

- self-supervised learning (SSL): Learning from unlabeled data by predicting parts of the input, e.g., next-token prediction. "self-supervised learning (SSL) method"

- temperature-scaled KL divergence: KL divergence computed after softening logits with a temperature parameter to emphasize relative probabilities. "temperature-scaled KL divergence"

Practical Applications

Summary

Below are practical, real-world applications derived from the paper’s Semantic Soft Bootstrapping (SSB) method, which improves LLM reasoning via RL-free self-distillation that leverages hinted teacher contexts and logit-level supervision. Applications are grouped by deployability and linked to relevant sectors. Each item includes potential tools/workflows and notes on assumptions or dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These applications can be deployed now using the released code/model and modest compute (e.g., single A100 GPU), especially for tasks with verifiable, discrete final answers.

Industry

- Math and quantitative tutoring in EdTech

- Sector: Education

- What: Deploy a “mistake-aware” math tutor that provides robust, step-by-step solutions and explicitly cautions against common errors observed in student rollouts.

- Tools/workflows: Use the paper’s refine-and-explain teacher prompt; auto-curate teacher–student pairs from existing question-answer banks; distill logits via LoRA adapters on domain-specific corpora.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires datasets with ground-truth final answers; consistent formatting (e.g., boxed answers or equivalent); base model must already generate mixed correct/incorrect rollouts to enable contrastive hinting.

- Unit-test–anchored code assistants

- Sector: Software

- What: Fine-tune coding LLMs to reason more reliably by using unit tests as verifiable rewards (final answers), synthesizing robust explanations from common failing traces.

- Tools/workflows: SSB pipeline with unit tests as “answers” and failing test logs as representative incorrect traces; integrate into CI via GitHub Actions to continuously distill “teacher logits” from test-guided corrections.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires high-quality, deterministic test suites; tasks should end in a pass/fail state that is easy to parse; adequate base-model coding capability.

- Spreadsheet formula and financial calculator assistants

- Sector: Finance, Enterprise Productivity

- What: Build assistants that produce correct formulas and computations for finance/accounting and proactively warn about typical pitfalls (e.g., off-by-one ranges, mismatched periods).

- Tools/workflows: Curate domain problems with verified outcomes (e.g., tax brackets, loan amortization); run SSB to align student predictions with teacher’s robust solutions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of authoritative calculations; stable formatting standard for the “final answer”; careful domain scoping to avoid ambiguous outputs.

- Low-compute post-training for enterprise LLMs

- Sector: Software/ML Ops

- What: Replace or complement RLVR pipelines with SSB to reduce reward hacking risk, token bloat, and compute costs while improving pass@1 reasoning on verifiable tasks.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-specific SSB finetuning as an internal service; logit storage and KD training; evaluation harness for pass@1 gains.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to problem–answer datasets; secure storage of logits; LoRA integration with model governance and licensing constraints.

Academia

- Reproducible, affordable reasoning improvement baselines

- Sector: Research & Education

- What: Use the released Qwen2.5-3B SSB pipeline to establish baseline improvements on math benchmarks without expensive RLVR runs; extend to new verifiable tasks (logic puzzles, symbolic integration with CAS).

- Tools/workflows: Experiment with KL-only distillation, teacher-logit extraction, and PEFT via LoRA; analyze sample efficiency and scaling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires access to datasets with discrete, verifiable answers; careful prompt engineering for teacher and student contexts.

- Automated dataset curation from student/model attempts

- Sector: Education Research

- What: Auto-curate paired teacher–student examples (correct vs. most common incorrect) from classroom or MOOC submissions to build robust, mistake-aware tutors.

- Tools/workflows: Ingestion of anonymized student responses; parse final answers and select representative errors; teacher refinement; KD-based student finetuning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy-compliant data handling; consistent grading scheme; alignment to curriculum standards.

Policy and Public Sector

- Eligibility and forms calculators with verified outcomes

- Sector: Government Services

- What: Build calculators for benefits eligibility, fee determinations, and tax estimates that produce verifiable, discrete outputs and flag common user errors.

- Tools/workflows: Use regulatory rules as ground-truth; SSB pipeline for robust explanations and error cautions; integrate with e-government portals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear, machine-checkable rules; formalized verification of outputs; strict oversight for public-facing deployments.

Daily Life

- Personal exam prep and problem-solving assistants

- Sector: Consumer Apps

- What: Apps that provide step-by-step math/logic solutions, highlight common mistakes, and ensure a verified final answer—useful for students and self-learners.

- Tools/workflows: Lightweight on-device or cloud finetunes using SSB with small curated sets (as in the paper’s 256-sample GSM8K setup).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Curated question-answer sets; stable UX to show final answer and cautionary notes.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, or infrastructure (e.g., larger models, richer verifiers, broader domains beyond math).

Industry

- Verified tool-use reasoning systems

- Sector: Software, DevTools

- What: Combine SSB with tool-use (e.g., search, calculators, compilers) so the teacher synthesizes robust reasoning from correct/incorrect tool traces and distills to a student that reliably orchestrates tools without hints.

- Tools/workflows: Tool-augmented rollouts; logs for correct vs. common wrong tool sequences; KD on answer tokens plus tool-call selections.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality tool instrumentation and verifiers; careful handling of non-deterministic tools.

- Robotics task planning with simulation-based verification

- Sector: Robotics/Automation

- What: Use simulators to label plans as success/failure (verifiable outcomes) and apply SSB to distill robust planning policies that avoid common failure modes.

- Tools/workflows: Generate multiple rollouts per task; select representative failures; teacher refinement with safety cautions; distill to student policy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable simulators; mapping from plans to verifiable success metrics; bridging from text to action policies.

- Energy and operations optimization assistants

- Sector: Energy, Operations Research

- What: Distill reasoning models to propose schedules or resource allocations that satisfy constraints validated by solvers/digital twins.

- Tools/workflows: Construct problems with solver-verified final states; capture common constraint violations; refine and distill robust strategies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate digital twins/solvers; scalable problem generation; interdisciplinary validation.

Academia

- Cross-domain scaling laws and sample efficiency studies

- Sector: AI Research

- What: Systematically paper SSB’s compute–accuracy tradeoffs across model sizes, domains (program synthesis, scientific Q&A), and rollout counts; compare to RLVR pipelines.

- Tools/workflows: Large-scale experiments with different temperatures, contrast pairs, KD strategies (e.g., CE+KL); error taxonomy analyses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to diverse datasets with reliable verifiers; sustained compute for multi-domain scaling.

- Integration with theorem provers and symbolic systems

- Sector: Scientific Computing

- What: Use formal proof checkers (or CAS) to verify final answers; distill robust mathematical reasoning that generalizes beyond heuristic CoT.

- Tools/workflows: Teacher prompts incorporating correct/incorrect proof sketches; KD on answer tokens linked to prover-validated outcomes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tight integration with formal systems; domain-adapted parsing and verification pipelines.

Policy and Governance

- Standardized “verified-output” training protocols

- Sector: AI Policy/Model Governance

- What: Develop guidance that prioritizes logit-level distillation with verifiable outcomes over sparse-reward RL to mitigate reward hacking and improve transparency.

- Tools/workflows: Compliance frameworks for storing teacher logits; audit trails of hinted vs. hint-free contexts; reproducibility checklists.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on verification standards; privacy and IP constraints on training data and logits.

- Certified reasoning systems for regulated domains

- Sector: Healthcare, Finance, Public Administration

- What: Certification pathways for models trained on tasks with strict verifiers (e.g., dosage calculators, tax computations), emphasizing error-aware explanations.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-specific test suites; adversarial “common wrong” case libraries; post-deployment monitoring for drift.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust, legally accepted verifiers; risk management; human-in-the-loop oversight.

Daily Life

- Broad subject tutors with curriculum-aligned verification

- Sector: Education

- What: Scale SSB to multiple subjects (physics, chemistry, economics) using curriculum-specific problem banks and verifiers, producing tutors that warn about typical misconceptions.

- Tools/workflows: Subject-specific contrastive hinting (correct vs. common wrong); KD on verified answer tokens; LMS integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality, diverse question–answer datasets; reliable graders/verifiers per subject.

Cross-Cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- Verifiable tasks: SSB depends on tasks with discrete, checkable final answers (or strong verifiers). Open-ended tasks without clear correctness signals reduce feasibility.

- Mixed rollouts: The base model must produce a mix of correct and incorrect attempts to enable contrastive hinting. If either set is empty, examples are discarded.

- Formatting/parsing: The pipeline assumes consistent final-answer formatting (e.g., boxed answers) or equivalent structured parsing. Adapting to new formats requires robust parsers.

- Data quality and coverage: Gains depend on curated problem–answer pairs that reflect target domain distributions (math in the paper). Generalization to other domains needs domain-specific curation.

- Compute and infrastructure: While more efficient than RLVR, SSB still requires GPU time for rollouts, logit extraction, and distillation; secure storage of teacher logits; prompt engineering.

- Safety and oversight: Verified outputs can be wrong if the verifier is flawed; regulated applications (healthcare, finance) need stringent validation and human oversight.

- Licensing and governance: Model and dataset licenses, privacy constraints (especially for student submissions), and logit storage policies must be respected.

These applications leverage SSB’s key advantages—compute efficiency, RL-free training, reduced reward hacking, and improved pass@1 accuracy—especially in domains where correctness can be parsed and verified.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.