When do spectral gradient updates help in deep learning? (2512.04299v1)

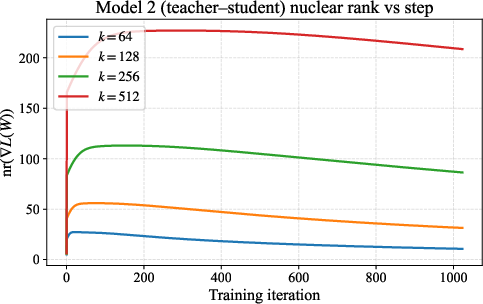

Abstract: Spectral gradient methods, such as the recently popularized Muon optimizer, are a promising alternative to standard Euclidean gradient descent for training deep neural networks and transformers, but it is still unclear in which regimes they are expected to perform better. We propose a simple layerwise condition that predicts when a spectral update yields a larger decrease in the loss than a Euclidean gradient step. This condition compares, for each parameter block, the squared nuclear-to-Frobenius ratio of the gradient to the stable rank of the incoming activations. To understand when this condition may be satisfied, we first prove that post-activation matrices have low stable rank at Gaussian initialization in random feature regression, feedforward networks, and transformer blocks. In spiked random feature models we then show that, after a short burn-in, the Euclidean gradient's nuclear-to-Frobenius ratio grows with the data dimension while the stable rank of the activations remains bounded, so the predicted advantage of spectral updates scales with dimension. We validate these predictions in synthetic regression experiments and in NanoGPT-scale LLM training, where we find that intermediate activations have low-stable-rank throughout training and the corresponding gradients maintain large nuclear-to-Frobenius ratios. Together, these results identify conditions for spectral gradient methods, such as Muon, to be effective in training deep networks and transformers.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

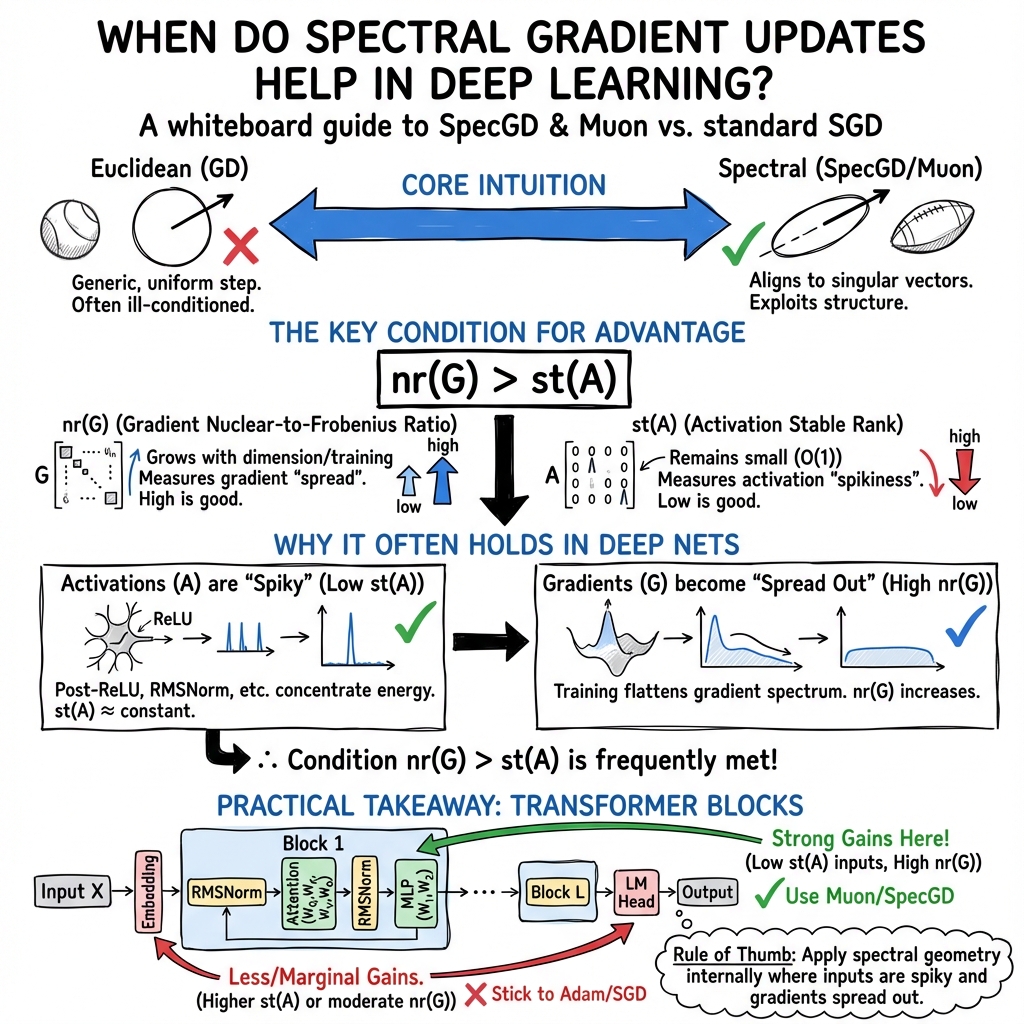

This paper studies a new way to update the weights in deep neural networks called spectral gradient methods (like the Muon optimizer). The main idea is to decide when these “shape-aware” updates should beat the usual gradient descent used in optimizers like SGD or Adam.

What question does the paper answer?

In simple terms: When should we expect a spectral update to reduce the training loss more than a standard gradient step?

The authors give a clear, layer-by-layer rule of thumb: a spectral update is favored when the incoming data to a layer is simple in shape (it mostly lies in a few directions) and the layer’s gradient spreads strongly across many directions.

How do they approach the problem?

To explain their approach, here are the key ideas in everyday language:

- Stable rank of activations: Imagine your network squashes the data so that it mostly lives in a small number of “lanes.” The stable rank measures how many lanes the data really uses. Low stable rank means “few important directions.”

- Nuclear rank of the gradient: Think of the gradient (the direction you push the weights) as spreading its effort across many directions; the nuclear rank measures how much the gradient’s strength is spread out. Large nuclear rank means “many directions matter.”

- Two kinds of updates:

- Euclidean (standard) gradient step: Follows the plain gradient, using the usual notion of distance.

- Spectral step: Follows the gradient’s main directions (its “shape”) and scales the step using a different, spectrum-based measure.

Their central condition compares these two quantities for each layer:

- Spectral update beats Euclidean update when:

- Here, is the gradient’s nuclear rank (sum-of-strengths squared divided by overall energy), and $st(A_{\ell-1}) = \frac{\|A_{\ell-1}\|_F^2}{\|A_{\ell-1}\|_{\op}^2}$ is the stable rank of the incoming activations (how many lanes are used).

- In words: spectral updates help when the gradient is spread out across many directions but the incoming data mostly sits in a few directions.

To back this up, they:

- Prove that post-activation matrices (the “data” flowing into each layer) often have low stable rank at initialization—in simple feedforward networks and transformer blocks.

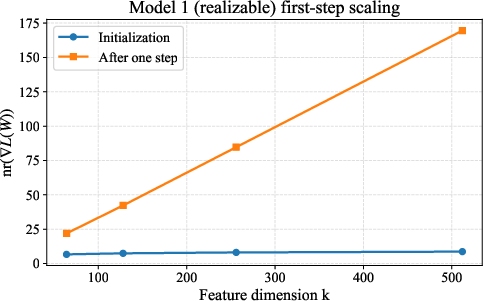

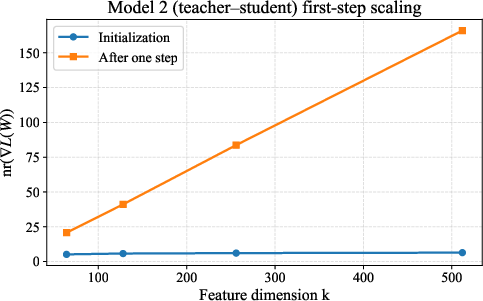

- Show in simple random-feature models that the gradient’s nuclear rank becomes large quickly and stays large for a long window in training.

- Measure these quantities in real training runs (e.g., NanoGPT-scale LLMs), finding low stable ranks for internal activations and high nuclear ranks for corresponding gradients.

What did they find?

The main findings are:

- Low-stable-rank activations are common.

- In feedforward networks, many layers produce activations with low stable rank (few important directions), even at random initialization.

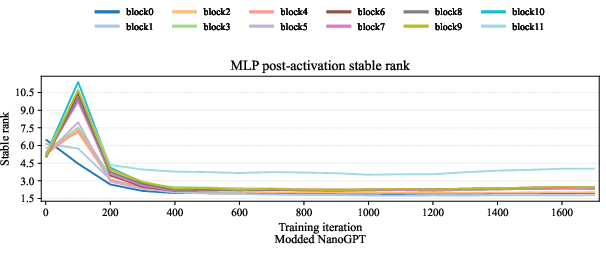

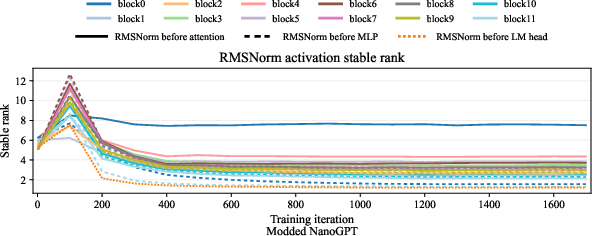

- In transformers (with RMS normalization), the activations feeding attention and MLP weights also have low stable rank at initialization and throughout training.

- Spectral steps can promise larger one-step loss reduction than standard steps when the condition holds.

- Under low-stable-rank data, the predicted advantage of spectral steps grows with the data dimension (i.e., bigger models benefit more).

- The advantage isn’t just an early, temporary effect.

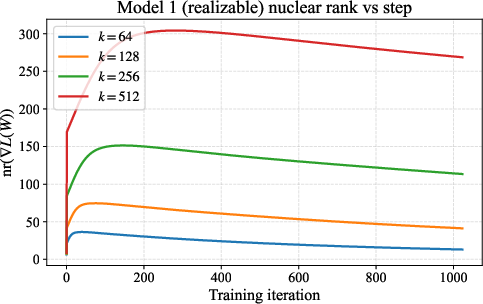

- In spiked random-feature models, the gradient’s nuclear rank becomes large after a short burn-in and stays large over a long stretch of iterations, so spectral updates would keep outperforming Euclidean steps over a significant portion of training.

- Real experiments match the theory.

- Synthetic regression tests: spectral steps reduce the loss faster than standard steps when the condition holds.

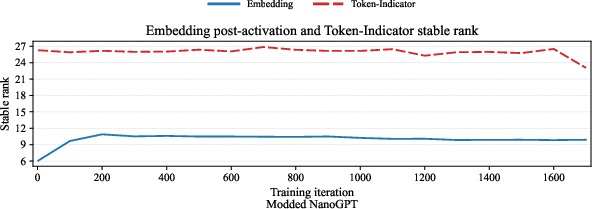

- NanoGPT-scale training: internal activations (RMS-normalized states and MLP post-activations) stay low-stable-rank, while gradients for attention and MLP weights keep large nuclear ranks—predicting a strong advantage for spectral updates on these blocks.

- Where spectral updates are less helpful.

- If the incoming data is not low-stable-rank or the gradients aren’t spread out (for example, with certain “gated” activations like SwiGLU in specific setups), the condition can fail and spectral updates may be slower than standard ones.

Why does this matter?

- Practical guidance: The paper explains why optimizers like Muon work well in LLMs and deep networks, especially on the “inside” layers (attention and MLP weights), where the activations are low-stable-rank and gradients have large nuclear ranks. It also explains why practitioners often keep embeddings and the final language-model head on standard (AdamW-like) updates: for those parts, the condition holds less strongly.

- Scaling benefits: As models get bigger, the advantage of spectral methods can grow, making them more appealing for training large networks efficiently.

- Better design: The simple layerwise test ( vs. ) can help decide where to apply spectral updates, rather than using the same update everywhere.

Takeaway

If the data going into a layer mostly lives in a few directions (low stable rank) and that layer’s gradient spreads across many directions (high nuclear rank), then spectral updates should reduce the loss more than standard gradient steps. This situation shows up often inside modern deep networks and transformers, which is why spectral optimizers like Muon can be especially effective there.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that remain after this paper, aimed to guide future research.

- One-step analysis scope: The core comparisons are based on single-step quadratic models; there is no global convergence analysis for spectral updates over full training trajectories in realistic deep networks (nonconvexity, residual connections, normalization, gating), nor under standard training regimens (SGD, momentum, weight decay, schedules, mixed precision).

- Muon/AdamW mismatch: The theory analyzes Euclidean GD vs SpecGD but does not formally treat the optimizer used in practice (Muon with momentum and Newton–Schulz polar approximation) or AdamW-style updates. It remains unclear how the nuclear-rank versus stable-rank criterion maps to guarantees for these optimizers, or how momentum and adaptive statistics alter the predicted advantage.

- Gradient nuclear rank beyond toy models: Outside spiked random-feature regression, there is no theoretical characterization of when and why gradient nuclear ranks become large and persist in real architectures (MLPs, transformers) during training, nor how this depends on depth, width, batch size, loss curvature, or data distribution.

- Stable rank beyond initialization: Theoretical guarantees for low-stable-rank post-activations are largely at Gaussian initialization (and special cases like quadratic activations). There is no proof that low stable rank persists under training with non-quadratic activations (e.g., ReLU/GELU), residual connections, RMSNorm, attention, or real data distributions.

- Transformer details omitted in proofs: The transformer analysis suppresses masking, multi-head attention, RoPE, and parameterized RMSNorm; there is no formal proof that the stable-rank bounds and layerwise descent criteria survive these components or their learned parameters.

- Role of attention softmax kernel P: The operator norms and curvature effects involving the attention kernel

P = softmax(K^T Q / sqrt(d))are treated heuristically; bounds on||P||_opand its training-time dynamics (and their impact on effective curvature and layerwise step sizes) are not established. - Gated activations (e.g., SwiGLU) regime: The paper briefly notes a counterexample class where spectral updates can be worse (gated activations) but does not develop a theory predicting when gating destroys the condition

nr(G) >= st(A), nor robust criteria for detecting “spectral-unfavorable” regimes. - Adaptive per-layer selection: There is no principled, provably correct procedure for deciding which layers should receive spectral vs Euclidean updates over training (e.g., based on measured

nr(G_ell)/st(A_{ell-1})), nor analyses of stability and performance for such adaptive policies. - Step-size selection and safety: Blockwise step sizes use coarse curvature bounds; there is no line-search or adaptive step-size rule for spectral directions with guarantees, nor stability analyses (e.g., conditions preventing overshoot when

||G||_*is large, interaction with weight decay, or need for clipping). - Efficient approximation of spectral quantities: Computing

||G||_*,||G||_F, and the polar factor is expensive in large models. The paper does not provide scalable approximations with error-controlled guarantees (e.g., randomized SVD, low-rank sketches) or analyze how approximation error affects the descent inequality and training outcomes. - Beyond matrix parameters: Biases, vector parameters (e.g., LayerNorm/RMSNorm gains), convolutional kernels (weight sharing, 4D tensors), and embedding geometry are not treated. It is unclear how spectral updates should be generalized to these parameter types, or whether alternative norms (e.g.,

ℓ1→ℓ2for embeddings) yield stronger theory or practice. - Embedding block geometry: The suggestion that the embedding block may be better analyzed under

ℓ1→ℓ2geometry is not pursued. A formal framework comparing spectral vsℓ1→ℓ2updates for one-hot inputs, with explicit curvature constants and thresholds, remains open. - Generalization and implicit bias: The work analyzes training loss decrease but not generalization. Whether spectral geometry alters implicit bias (e.g., towards low-rank weights or certain representation structures), affects calibration, or improves downstream performance remains an open empirical and theoretical question.

- Scaling laws and data dependence: The causes of low stable rank (e.g., normalization, residual pathways, data distribution skew, sequence length) and how stable/nuclear ranks scale with width, depth, and dataset statistics are not theoretically characterized. Predictive scaling laws for

st(A)andnr(G)across architectures and datasets are missing. - Interaction with regularization: Effects of weight decay, dropout, label smoothing, and other regularizers on the spectral vs Euclidean advantage are not analyzed; in particular, how regularization modifies curvature bounds and the nuclear/stable-rank criterion is unknown.

- Robustness to stochasticity: The theory largely assumes full-batch or smooth losses; the impact of stochastic gradients (variance, sampling noise) on the nuclear-rank advantage and the stability of spectral updates is not studied.

- Wall-clock and compute trade-offs: Empirical results focus on small-to-medium models (e.g., NanoGPT). There is no systematic evaluation of wall-clock speedups, memory costs, numerical stability, and throughput at larger scales, nor a cost–benefit analysis of exact vs approximate spectral steps.

- Formal multi-block interactions: While the layered Taylor model includes mixed Hessian bounds, there is no rigorous multi-step analysis of how spectral updates on some blocks affect curvature and gradients of others across time, and whether inter-block couplings can negate or amplify the predicted one-step advantage.

- Refined curvature modeling: The analysis uses coarse bounds with global

C_F(W)andC_op(W). Developing tighter, block-specific curvature models (including attention dynamics and normalization effects) and showing how they change the thresholds fornr(G_ell) >= st(A_{ell-1})remains open. - Failure modes and diagnostics: The paper does not provide diagnostics to detect when spectral updates are likely harmful (e.g., small

nr(G)or largest(A)), nor procedures to switch geometry dynamically with guarantees against degradation.

Glossary

- blockwise curvature coefficients: Layer-specific constants controlling curvature in the quadratic training model. "we obtain feature-based blockwise curvature coefficients"

- decoder-only transformer: A transformer architecture that uses only decoder blocks without an encoder. "For decoder-only transformer architectures with RMS-normalized attention/MLP blocks,"

- dual norm: The norm paired with a given norm in convex analysis, used to measure gradient magnitude for guaranteed descent. "the guaranteed function decrease achieved by \mathtt{GD} and \mathtt{SpecGD} is fully determined by the dual norm of the gradient:"

- Frobenius norm: Matrix norm equal to the square root of the sum of squares of all entries. "Thus \mathtt{GD} and \mathtt{SpecGD} impose the (Euclidean) Frobenius norm and the (non-Euclidean) operator norm on the domain, respectively."

- Gaussian initialization: Initializing parameters or inputs with values drawn from a Gaussian distribution. "post-activation matrices have low stable rank at Gaussian initialization in random feature regression,"

- Hessian: The matrix of second derivatives of a scalar function, encoding curvature. "study the full Hessian of the composite loss."

- K-FAC: An optimizer using Kronecker-factored approximations to curvature for efficient preconditioning. "Kronecker-factored schemes (K-FAC~\cite{martens2015kfac}, Shampoo~\cite{gupta2018shampoo})."

- Lipschitz: A smoothness condition bounding how fast a function (or its gradient) can change. "a smooth loss f on WA for which the gradient \nabla f is -Lipschitz."

- majorization principle: A technique that upper-bounds a difficult objective with a simpler surrogate to derive updates. "The usual starting point for first-order algorithms is based on the majorization principle:"

- MUON: A momentum-based spectral optimizer operating on gradient spectra. "The recently proposed optimizer MUON~\cite{jordan2024muon} implements a momentum-based variant of this spectral update,"

- Newton-Schulz algorithm: An iterative method for approximating matrix inverses/polar factors. "the polar is approximated by the Newton-Schulz algorithm,"

- nuclear norm: Sum of singular values of a matrix; promotes low-rank directions in spectral updates. "thus moving in a direction with the same singular vectors but unit spectral norm and step length given by the nuclear norm."

- nuclear rank: The ratio measuring spread of singular values in a gradient. "we will refer to this ratio as the nuclear rank of and denote it by"

- operator norm: Largest singular value of a matrix; measures maximal amplification of vectors. "Thus \mathtt{GD} and \mathtt{SpecGD} impose the (Euclidean) Frobenius norm and the (non-Euclidean) operator norm on the domain, respectively."

- polar factor: The unitary/orthogonal factor in a matrix’s polar decomposition aligning with singular vectors. "replaces the raw gradient with its polar factor,"

- preactivation: Linear transformation outputs before applying nonlinearity in a neural layer. "preactivation matrices "

- random feature regression: A simplified model using fixed nonlinear features to analyze training dynamics. "post-activation matrices have low stable rank at Gaussian initialization in random feature regression,"

- RoPE: Rotary Position Embeddings, a positional encoding method for transformers. "positional encodings (e.g.\ RoPE)"

- RMSNorm: Root-mean-square normalization applied per token across features. "A{\mathrm{rms} = \mathrm{RMSNorm}(X),"

- RMS-normalized hidden states: Hidden representations rescaled by RMS normalization. "RMS-normalized hidden states entering "

- Scion: A spectral optimizer closely related to MUON. "spectral optimizers such as MUON and Scion~\cite{shen2025convergence,pethick2025scion}"

- Shampoo: A preconditioned optimizer using second-order information via matrix factorizations. "Kronecker-factored schemes (K-FAC~\cite{martens2015kfac}, Shampoo~\cite{gupta2018shampoo})."

- spectral gradient descent (SpecGD): An optimizer that updates along the gradient’s polar direction with nuclear-norm scaling. "Spectral gradient descent method (SpecGD~\cite{carlson2015preconditioned})"

- spectral norm: Largest singular value of a matrix; equals the operator norm. "thus moving in a direction with the same singular vectors but unit spectral norm"

- stable rank: $\|A\|_F^2/\|A\|_{\op}^2$, a dimension-free rank proxy based on norms. "The right-hand side is precisely the stable rank"

- submultiplicativity: Property that the norm of a product is bounded by the product of norms. "but submultiplicativity still isolates their contribution:"

- SwiGLU: A gated activation combining Swish (SiLU) with a linear gate. "replacing the ReLU nonlinearity with a SwiGLU activation."

- Taylor expansion: Polynomial approximation of a function around a point, used to derive update bounds. "the function may be rewritten as a Taylor-expansion:"

- teacher–student: A modeling setup where a student network learns from outputs of a teacher model. "in both realizable and teacher–student variants we prove"

- spiked random feature models: Random feature models augmented with low-rank signal components. "In spiked random feature models we then show that,"

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper establishes a simple, layerwise criterion for when spectral gradient updates (e.g., Muon, SpecGD) should outperform standard Euclidean gradient methods in training deep networks and transformers. The key condition compares the “nuclear rank” of the gradient block to the stable rank of the incoming activations:

- Nuclear rank:

nr(G) = ||G||_*^2 / ||G||_F^2 - Stable rank:

st(A) = ||A||_F^2 / ||A||_op^2

Spectral updates are predicted to yield larger loss decrease when nr(G) ≥ st(A). The paper proves that post-activation matrices often have low stable rank (bounded by a small constant independent of width/sequence length) in feedforward networks and RMS-normalized transformer blocks; it also shows that gradient nuclear ranks can be large over prolonged training windows, especially early in training and in higher dimensions. The authors validate these predictions in synthetic regression and NanoGPT-scale LLM training.

Below are practical, real-world applications derived from these findings, grouped by immediacy, with sector links, emergent tools/workflows, and assumptions.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now with existing tooling (e.g., PyTorch/JAX, Muon/SpecGD prototypes, and the authors’ public code).

- AI/Software (Transformers and LLM pretraining and fine-tuning)

- Application: Use spectral updates on internal 2D weight blocks (attention and MLP) and Euclidean/adaptive updates (e.g., AdamW) on embeddings and LM heads.

- What to do:

- Apply spectral steps to blocks whose incoming activations are low-stable-rank:

- Attention: W_Q, W_K, W_V, W_O with incoming RMS-normalized activations.

- MLP: W_1 (RMS-normalized inputs to MLP), W_2 (MLP post-activations).

- Keep token embeddings and LM head on AdamW or Euclidean steps; consider alternative geometry (e.g., ℓ1→ℓ2 norm) for embeddings.

- Use the rule of thumb: switch a block to spectral updates when

nr(G_ℓ) ≥ st(A_{ℓ−1}). - Expected benefits:

- Faster early training (dimension-dependent speedups).

- Potential reduction in training time/energy for LLMs.

- Tools/workflows:

- Integrate Muon-like updates into training loops; use Newton–Schulz for polar factor approximation.

- Instrument training to track

st(A)andnr(G)per block; build dashboards that flag blocks for spectral updates. - Reference code: https://github.com/damek/specgd/

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Activations remain low-stable-rank under RMSNorm and typical initialization.

- Gradients maintain large nuclear-to-Frobenius ratios during a sizable training window.

- Implementation can tolerate added compute for spectral operations (approximate polar).

- AI/Software (MLPs for recommendation systems, tabular prediction, control)

- Application: In deep MLPs, apply spectral updates to intermediate layers (where post-activations are empirically low-stable-rank); use Euclidean steps on the input/output heads.

- Tools/workflows:

- Per-layer optimizer assignment using

nr(G_ℓ)/st(A_{ℓ−1})thresholds. - Step sizes aligned with feature-based curvature estimates: use

L_F ~ ||A||_op^2for Euclidean andL_op ~ ||A||_F^2for spectral steps. - Assumptions/dependencies:

- Input features may not be low-stable-rank; the advantage is concentrated in internal layers.

- Academia (Research methodology and diagnostics)

- Application: Use

st(A)andnr(G)as diagnostic signals to paper training geometry across architectures, losses, and datasets. - Tools/workflows:

- Benchmark spectral versus Euclidean updates under controlled changes (activation choice, normalization, depth/width).

- Reproduce toy and NanoGPT experiments; extend to other architectures/datasets.

- Application: Use

- Energy/Compute Efficiency (Industry and public-sector AI)

- Application: Reduce training cost in early epochs by prioritizing spectral updates where the condition holds; tune batch sizes and layerwise steps accordingly.

- Tools/workflows:

- Build energy-aware training schedulers that enable spectral updates during the “burn-in” window where

nr(G)is high. - Assumptions/dependencies:

- Gains depend on activation degeneracy and persist for a macroscopic window; monitor empirically.

- Robotics, Finance, Healthcare (sector-specific deep models)

- Application: For transformer-based time series models (finance), clinical LLMs (healthcare), and policy networks with MLPs (robotics), adopt the mixed optimizer strategy (spectral for internal blocks, Euclidean/AdamW for heads).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Stable-rank degeneracy appears in internal layers; validate with sector-specific datasets.

- Daily life (Practitioner-friendly training improvements)

- Application: Hobbyists and small labs training NanoGPT-scale models can adopt Muon (or SpecGD-like updates) for internal blocks to achieve faster loss reduction.

- Tools/workflows:

- Use modded-NanoGPT setups with Muon; monitor gradient nuclear ranks to confirm applicability.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, or engineering (approximate spectral operations, new optimizer design, standardization, or hardware support).

- Optimizer innovation (Mixed-geometry, per-layer, adaptive optimizers)

- Application: Design optimizers that switch geometry per block and over time:

- Spectral for low-stable-rank internal blocks.

- ℓ1→ℓ2 or column-norm geometry for embeddings (one-hot inputs).

- Blockwise step sizing using feature-based curvature (

L_ℓ^F = C_F ||A_{ℓ−1}||_op^2,L_ℓ^op = C_F ||A_{ℓ−1}||_F^2). - Tools/products:

- A PyTorch/JAX library that automatically measures

st(A)andnr(G)and schedules optimizers accordingly. - AutoML integration that tunes thresholds and momentum for spectral updates.

- Dependencies:

- Robust, low-overhead measurement of stable/nuclear ranks; scalable approximations.

- Hardware and kernel support (Accelerating spectral primitives)

- Application: GPU/TPU kernels for fast polar decomposition, SVD-like operations, and Newton–Schulz iterations tailored to gradient matrices.

- Tools/products:

- Vendor-supported libraries for spectral operations with mixed precision and low memory footprint.

- Dependencies:

- Numerical stability and efficient batching for large-scale training workloads.

- Architecture and normalization design (Spectral-friendly networks)

- Application: Architectures that naturally yield low-stable-rank activations (e.g., RMSNorm variants, specific MLP/attention configurations).

- Tools/workflows:

- Design principles that maintain low stable rank in hidden representations to amplify spectral advantages.

- Dependencies:

- Empirical validation across tasks; understanding interactions with gating (e.g., SwiGLU) where advantages may diminish.

- Training schedulers and curriculum learning

- Application: Schedulers that exploit the “high nuclear rank window” (Θ(d) to Θ(d log d) iterations) identified in spiked random-feature models:

- Start with spectral updates; gradually transition to Euclidean/adaptive methods as

nr(G)decreases. - Dependencies:

- Reliable detection of regime changes across tasks and architectures.

- Standardization and reporting (Policy and governance for efficient AI training)

- Application: Develop reporting standards that include optimizer geometry metrics (e.g.,

st(A),nr(G)trends), energy-per-token/epoch, and regime detection. - Tools/workflows:

- Procurement guidelines favoring spectral-aware training for public LLMs when diagnostics indicate applicability.

- Dependencies:

- Wider consensus on benchmarks, reproducibility, and safety implications.

- Application: Develop reporting standards that include optimizer geometry metrics (e.g.,

- On-device and edge training (Daily life, consumer devices)

- Application: Lightweight spectral approximations enabling faster fine-tuning on edge devices (e.g., smartphone LLM adapters).

- Tools/workflows:

- Compact kernels for Newton–Schulz polar approximations; mixed-precision routines.

- Dependencies:

- Hardware support; reduced-rank or low-width models; careful energy management.

Key Assumptions and Dependencies

The feasibility and impact of applications depend on several assumptions highlighted or implied by the paper:

- Stable-rank degeneracy:

- Post-activations in intermediate layers (MLPs, RMS-normalized transformer blocks) have low stable rank at initialization and often throughout training.

- This is proven under Gaussian initialization and observed empirically in NanoGPT-scale runs.

- Gradient nuclear rank:

nr(G)can become large after a short burn-in and remain high over a sizable training window, especially in high dimensions.

- Architecture and activation choices:

- RMSNorm and common nonlinearities (ReLU, GELU) favor the regime where spectral updates help.

- Gated activations (e.g., SwiGLU in certain random-feature settings) can reduce the advantage; practitioners should monitor

nr(G)andst(A)rather than assume benefits.

- Computation and implementation:

- Spectral updates require approximations to polar decomposition; Newton–Schulz is a practical approach but adds overhead.

- Layerwise step sizes should consider feature-based curvature estimates and blockwise differences.

- Generalization:

- The one-step comparison is geometric and does not directly account for momentum/adaptive accumulators (e.g., AdamW); nevertheless, it provides a robust heuristic for optimizer selection.

In sum, the paper offers an actionable rule-of-thumb and supporting theory to decide where spectral updates will help: apply them when incoming activations are low-stable-rank and gradient nuclear ranks are high, especially inside transformer and deep MLP blocks. This enables immediate training improvements and sets the stage for next-generation optimizers, tooling, and hardware that exploit spectral geometry.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.