Unique Lives, Shared World: Learning from Single-Life Videos

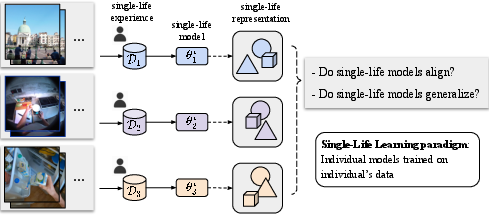

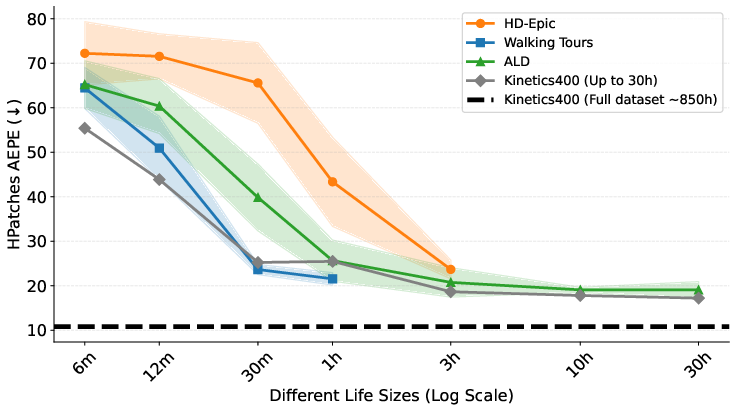

Abstract: We introduce the "single-life" learning paradigm, where we train a distinct vision model exclusively on egocentric videos captured by one individual. We leverage the multiple viewpoints naturally captured within a single life to learn a visual encoder in a self-supervised manner. Our experiments demonstrate three key findings. First, models trained independently on different lives develop a highly aligned geometric understanding. We demonstrate this by training visual encoders on distinct datasets each capturing a different life, both indoors and outdoors, as well as introducing a novel cross-attention-based metric to quantify the functional alignment of the internal representations developed by different models. Second, we show that single-life models learn generalizable geometric representations that effectively transfer to downstream tasks, such as depth estimation, in unseen environments. Third, we demonstrate that training on up to 30 hours from one week of the same person's life leads to comparable performance to training on 30 hours of diverse web data, highlighting the strength of single-life representation learning. Overall, our results establish that the shared structure of the world, both leads to consistency in models trained on individual lives, and provides a powerful signal for visual representation learning.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper explores a simple but powerful idea: can a computer learn about the 3D world just by watching videos from one person’s point of view (like a camera on someone’s glasses) and still end up understanding the world in a way similar to models trained on huge, mixed internet data? The authors call this the “single-life” learning paradigm. They show that even though each person’s life is unique, the shared rules of the physical world (like 3D geometry and how objects stay the same over time) help different models trained on single people’s videos learn very similar, useful features.

Key Questions

- If you train one vision model only on videos from one person, does it learn the same kind of geometric understanding as other models trained on other people?

- Do these “single-life” models work well on new tasks and new places they haven’t seen (like estimating depth in unfamiliar rooms)?

- How much video from one person is enough for good learning?

- What’s the best way to pick pairs of frames from a single life to teach geometry?

How They Did It (Methods)

Training from a single life

Think of a “life” as all the first-person videos recorded by one individual. Instead of mixing data from many people, the researchers train a separate model for each person’s videos, starting from scratch.

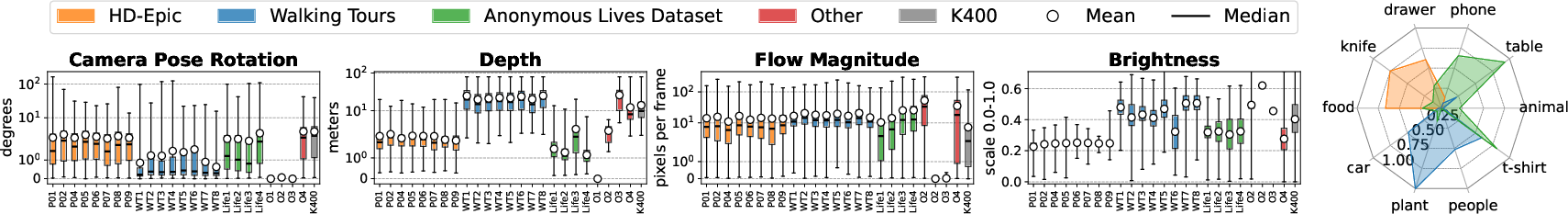

They use three kinds of single-life datasets:

- Indoor kitchens (a few hours per person).

- Outdoor city walking tours (about an hour per city).

- Week-long daily life recordings (up to 38 hours per person).

They also include “non-life” control videos (like a static security camera or a screen recording) to test what happens when the human, first-person motion is missing.

The learning task: cross-view completion

The models learn without labels, using a task called “cross-view completion.” Here’s an everyday analogy:

- Imagine two photos of the same place taken from different spots (like looking at your living room from the sofa and then from the door).

- The model hides parts of one photo and tries to fill them in using the other photo as a clue.

- This teaches the model how different views relate in 3D, because to fill in missing parts correctly, it must understand which patches (small parts of the image) in one view correspond to patches in the other.

Technically, the model splits images into patches, encodes them, and uses a transformer decoder with cross-attention to predict the masked patches. “Cross-attention” here is like matching puzzle pieces across two pictures.

Picking useful pairs: temporal and spatial pairing

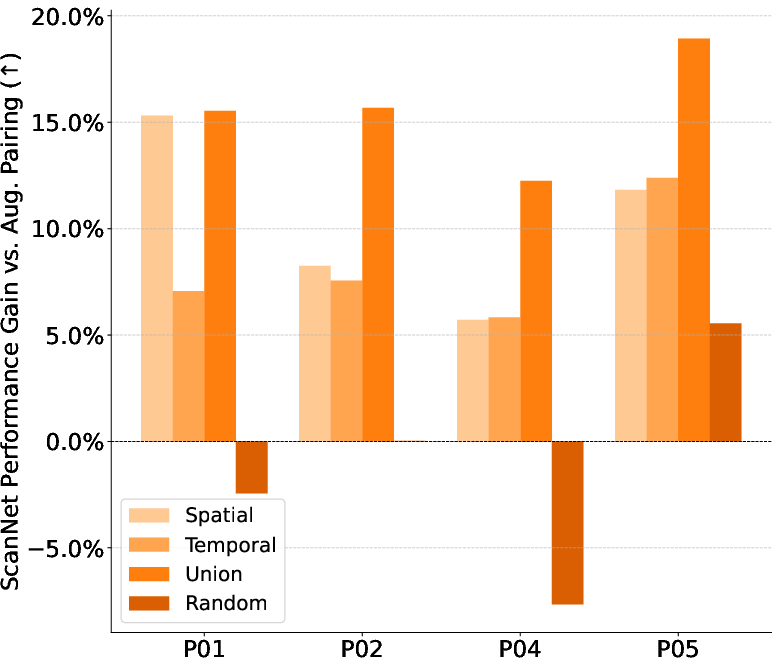

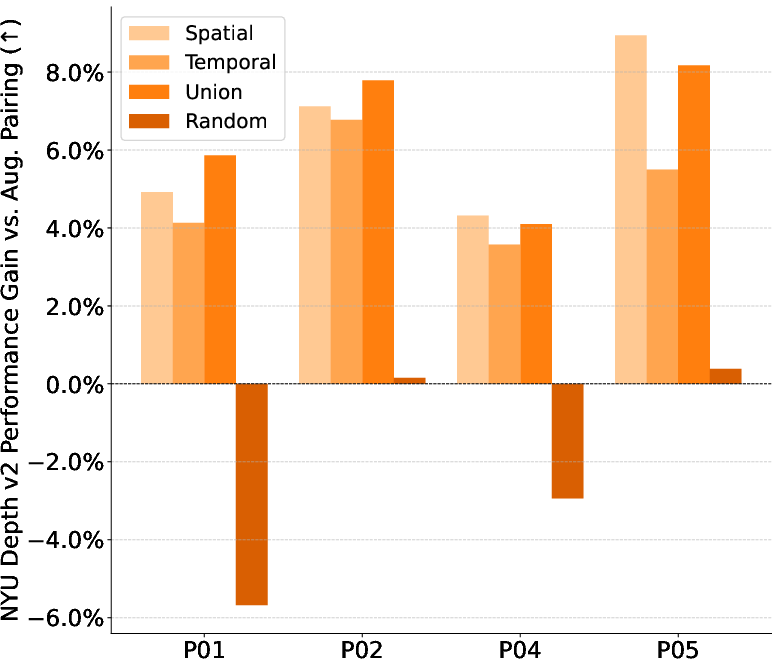

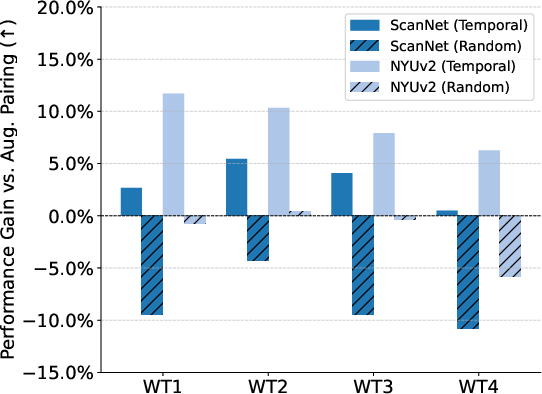

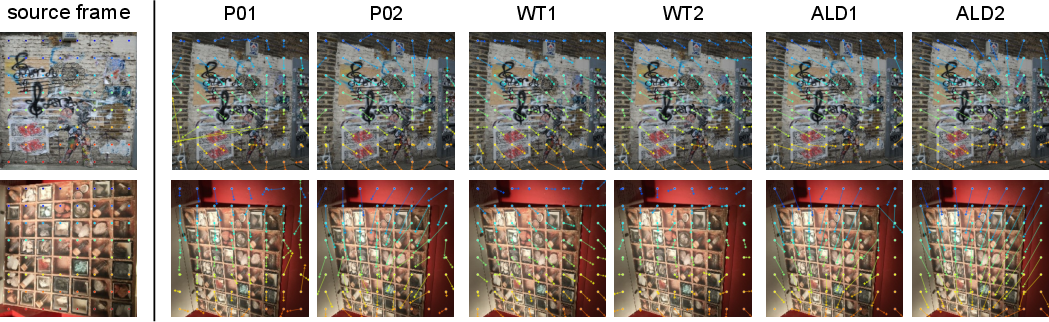

To learn geometry well, the two images in a pair need to show overlapping parts of the scene from different viewpoints. The paper tests two pairing strategies:

- Temporal pairing: Pick frames close together in time. In a video, nearby frames often look at the same place from slightly different angles, which is great for learning 3D relations.

- Spatial pairing: When available, use camera position and 3D info to choose frames that see the same area. This is like using a map to find two photos that look at the same region from different spots.

Combining both strategies worked best, but temporal pairing alone (which is easy to do) was surprisingly strong.

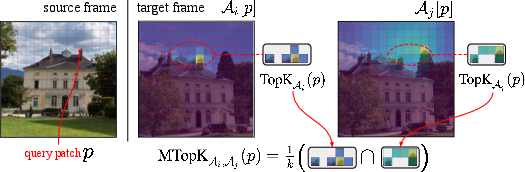

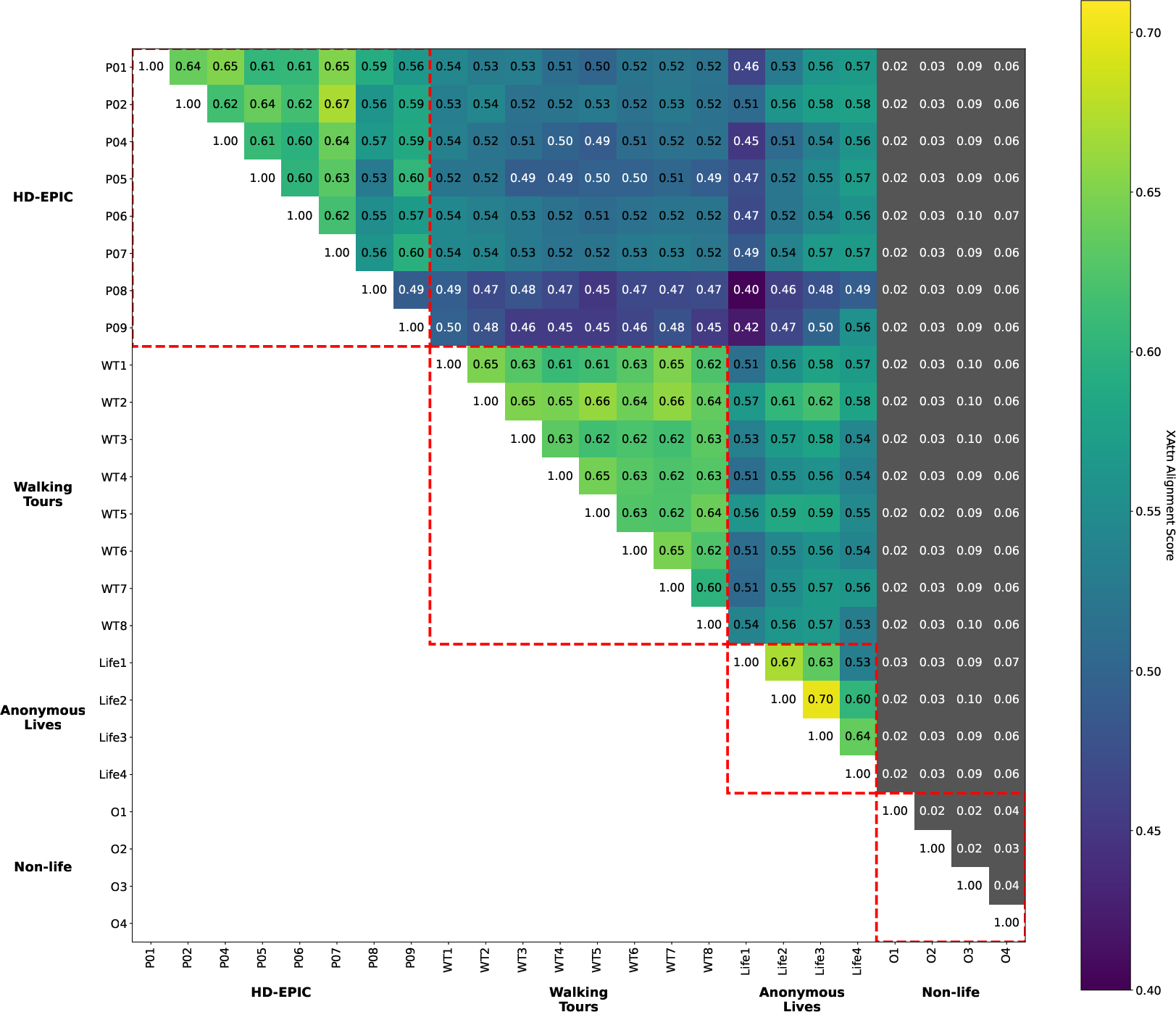

Checking if models think alike: the CAS score

The authors introduce a new way to measure whether two independently trained models “think” about image geometry in similar ways. They look at the cross-attention maps—basically, which patches in one image a model believes correspond to patches in the other. If two models tend to pick the same top matches, they get a high Correspondence Alignment Score (CAS), between 0 and 1.

Think of CAS like this: two students solve a matching puzzle; if they consistently circle the same pairs, they probably learned the same rules.

Testing generalization: depth and matching

They test the models on:

- Monocular depth estimation: Predict how far away things are in a single image (on NYU-Depth-v2 and ScanNet).

- Zero-shot correspondence: Match features across pairs of images under changes (on HPatches), using the model’s attention without extra training.

They mostly freeze the model and add a small attention “readout head” to adapt it to depth tasks—this is a light-weight way to test what the model already knows.

Main Findings

Here are the most important results, explained simply:

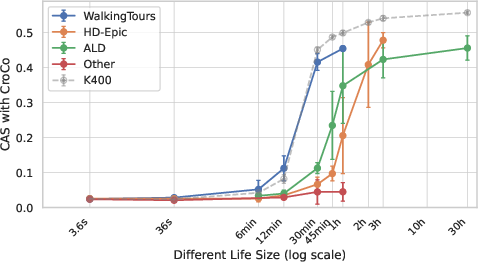

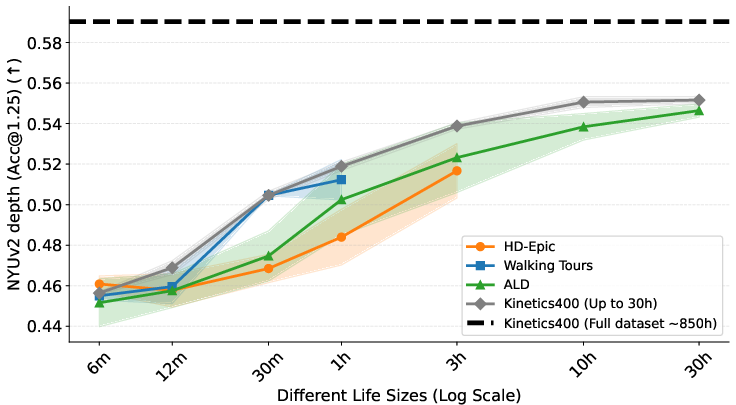

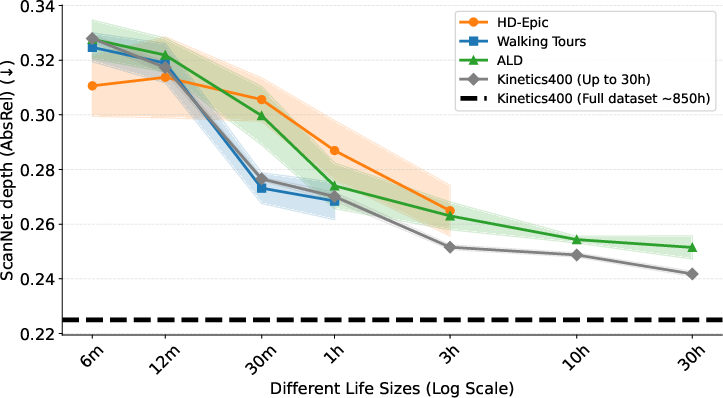

- Alignment emerges quickly: After about 30–60 minutes of a single person’s video, models start to align strongly—meaning they learn similar geometric thinking across different lives.

- Non-life videos don’t work: Models trained on videos without the human egocentric perspective (like a static camera or screen capture) barely align and don’t learn good geometry. Human motion and viewpoint changes are key.

- Comparable to diverse data at the same size: With around 30 hours from a single person, performance can match or even beat models trained on 30 hours of mixed, diverse internet clips for several tasks. That’s impressive given it’s just one life.

- Best pairing strategy: Using both temporal and spatial pairing yields the best results, but temporal pairing alone is already very effective and easy to apply.

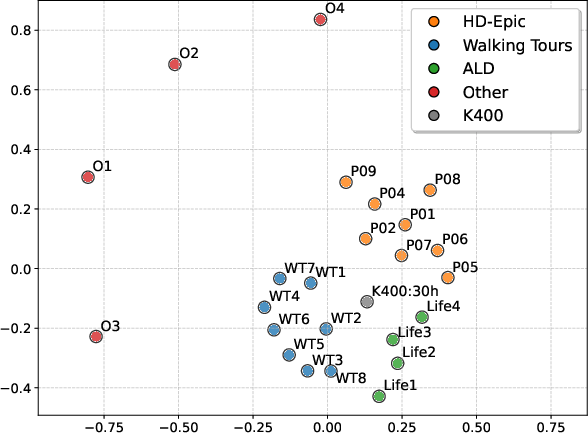

- Domain clusters: Models trained on similar environments (multiple kitchens vs. outdoor city walks) align more with each other and form clusters—showing that while the core geometry is shared, the “style” of a place leaves a fingerprint.

- Not tied to one architecture: Training a different self-supervised model (DINOv2) on single lives also gives strong geometric representations, suggesting the paradigm is broadly useful.

Why It Matters

This work shows that you don’t need huge, mixed datasets to learn strong geometric understanding for vision. A single person’s first-person video contains rich, repeated views of the same places that naturally teach 3D structure. Because the physical world is shared, models trained on different lives end up with similar internal “maps” of geometry.

This could make learning more:

- Efficient: You can get good performance from fewer, more coherent data sources.

- Personalized: Devices could learn from their owner’s environment and still generalize.

- Privacy-aware: Training on one person’s on-device data reduces the need to ship data elsewhere.

Implications and Impact

- Better on-device learning: Phones, AR glasses, or robots could learn useful 3D skills by watching their owner’s daily life, improving navigation, object interaction, and scene understanding.

- Reduced reliance on labels: Self-supervised, single-life training minimizes manual annotations and can scale naturally from regular video.

- Strong geometric priors: Single-life training produces models that understand depth and correspondence well, helping tasks like mapping, reconstruction, and stable tracking.

- Research direction: It encourages exploring longer single-life datasets (more than a week), richer pairing strategies, and combining geometry with semantics for broader abilities.

In short: even from one person’s videos, models can learn the shared rules of our world. That’s a big step toward simpler, more human-like learning in computer vision.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of unresolved issues that future research could address, grouped by theme for clarity.

Data scope and representativeness

- Limited number of long-term “lives” (only 4 ALD lives used for training; 1 held out) restricts conclusions about participant variability, habits, body morphology, height, and cultural/environmental diversity; quantify how alignment and generalization vary across more participants and geographies.

- Strong domain biases in the three sources (single kitchens in HD-Epic, urban strolls in Walking Tours, mixed but small ALD) leave out rural, driving, industrial, sports, low-light/night, adverse weather, and extreme-motion egocentric settings; test whether the Shared World hypothesis holds across these missing domains.

- Hardware heterogeneity (Aria vs. GoPro) is not analyzed; isolate and quantify the impact of camera optics, IMU availability, frame rate, stabilization, FOV, and rolling shutter on learned geometry and alignment.

- The key long-form dataset (ALD) is private; reproducibility and independent validation are limited. Provide public surrogates or protocols (e.g., synthetic egocentric streams) to replicate claims.

Pairing strategies and data requirements

- Spatial pairing assumes access to camera poses and 3D point clouds, which are often unavailable; develop and evaluate pose-free overlap mining (e.g., place recognition, retrieval, learned overlap classifiers) and compare their efficacy to pose-based pairing at scale.

- The impact of temporal-gap and overlap-threshold choices is not quantified; systematically ablate the temporal distance between paired frames and the degree of 3D overlap to find optimal regimes and robustness to dynamics.

- Random pairing unexpectedly helps on ALD; characterize when and why chance overlap suffices (e.g., long stationary segments) and design principled “weak supervision” pairing to exploit this effect without labels.

Alignment metric (CAS): validity, robustness, and scope

- CAS depends on decoder cross-attention from CroCo; it is not architecture-agnostic and was not applied to DINOv2. Develop a model-agnostic alignment metric (e.g., feature matching, equivariance tests) and compare to CAS.

- No sensitivity analysis of CAS to hyperparameters (top-k, layer/head selection, attention normalization, patch size, mask ratio); quantify stability and provide recommended defaults.

- The relationship between CAS and downstream performance is only suggested; formally measure correlation (e.g., Pearson/Spearman across models) and identify regimes where CAS fails to predict generalization.

- CAS is computed on held-out “test lives,” but domain composition may bias scores; test invariance of CAS across domains, resolutions, and photometric conditions, and report uncertainty (confidence intervals).

- CAS captures patch-level agreement but not geometric correctness; complement with geometry-grounded metrics (e.g., epipolar consistency, cycle-consistency, reconstruction error) to validate “functional” alignment.

Architecture, objectives, and training dynamics

- Architectural dependence is underexplored (mainly CroCo; limited DINOv2 results). Systematically compare objectives (masked reconstruction, contrastive, predictive modeling, flow prediction) and backbones (ViT sizes, CNNs, hybrids) under equal compute to identify what drives alignment/generalization in single-life regimes.

- Model capacity and scaling effects (depth/width, token size) on alignment emergence and downstream transfer are not reported; derive scaling laws linking model size, hours of life, and performance.

- Training order vs. shuffling: the role of temporal continuity and online learning is not tested; compare sequential vs. IID sampling, curriculum over time, and continual learning methods (to test sample efficiency and catastrophic forgetting).

Generalization breadth and evaluation coverage

- Downstream evaluation is geometry-leaning but narrow (depth on NYU/ScanNet, HPatches correspondence); add:

- Outdoor depth (e.g., KITTI, MegaDepth), low-light/nighttime, and wide-FOV datasets.

- Camera pose estimation, visual localization, SLAM/VO, surface normals, optical flow, novel view synthesis, 3D reconstruction benchmarks.

- Egocentric-specific tasks (hand-object interaction, action/object segmentation) to probe whether single-life geometry also supports semantics.

- The observed gap on ScanNet suggests benefits of diversity; analyze which diversity factors (scene count, pose spread, object variety) most affect transfer and design augmentations/mining to recover these from a single life.

- Robustness to dynamic scenes, moving distractors, specularities, and non-Lambertian surfaces is not quantified; introduce controlled tests to separate viewpoint vs. appearance changes.

Merging and transferring across lives

- The paper trains separate per-life models but does not explore combining them; investigate model stitching, feature-space alignment, or distillation to fuse multiple lives into a universal representation without raw data sharing.

- Test life-to-life adaptation: fine-tune a model on a new life and measure adaptation speed, data needs, and whether initial CAS predicts transfer efficiency.

- Explore whether ensembling or weight-space interpolation across aligned single-life models improves generalization.

Egocentric signal and control baselines

- “Non-life” controls are few and narrow (screen capture, static room, surveillance, Minecraft); expand to dynamic exocentric controls (handheld cinema, sports broadcast, drone, dashcam) to isolate which motion/overlap statistics are necessary and sufficient for alignment emergence.

- Directly compare egocentric vs. body/chest-mounted vs. helmet-mounted perspectives and different stabilization regimes to pinpoint the crucial characteristics of the egocentric signal.

Interpretability and failure analysis

- Provide qualitative and quantitative analyses of where alignment arises (e.g., hands vs. background, textureless regions, reflective surfaces); report per-region CAS and typical failure modes.

- Diagnose negative transfer: identify content or motion patterns that degrade alignment or generalization (e.g., repetitive textures, severe blur, rapid illumination shifts).

Privacy, security, and ethics

- Single-life models may memorize sensitive layouts and routines; assess privacy risks (membership/property inference, location leakage, re-identification) and evaluate privacy-preserving training (e.g., DP-SGD, feature anonymization) vs. utility trade-offs.

- Clarify consent, retention, and on-device/edge training feasibility for longer-term deployments; propose protocols for safe sharing of model weights without revealing personal environments.

Reproducibility and release

- Public release plans for code, CAS implementation, and standardized test-pair sets are unspecified; provide resources and detailed hyperparameters to enable rigorous replication.

- Document compute budgets and energy use for single-life training to compare practical feasibility against diverse-data baselines.

Theory and foundations

- The Shared World Hypothesis is empirically supported but lacks formal grounding; develop a theoretical model relating world regularities, overlap statistics, and objective biases to convergence of representations from distinct life streams.

- Clarify whether alignment reflects true geometric convergence or inductive biases of the architecture/objective; design causal tests (e.g., synthetic worlds with controlled physics) to disentangle these factors.

Glossary

- 3D Euclidean geometry: The mathematical structure of 3D space governed by Euclidean axioms; used to model real-world spatial relations and transformations. "Structural properties such as 3D Euclidean geometry and object permanence are universals that leave a consistent imprint on all visual data."

- Absolute Relative Error (AbsRel): A depth-evaluation metric computed as the mean of |predicted−true|/true over pixels. "We report mean of the absolute relative error (AbsRel)~\citep{ranftl2021vision} on the validation set which is computed as "

- AEPE (Average End-Point Error): A correspondence metric measuring the average Euclidean distance between predicted and ground-truth optical flow vectors. "We report the mean Average End-Point Error (AEPE) across all pairs which is the average Euclidean distance between predicted and the ground truth optical flow."

- Attentive probing: A probing method that trains a lightweight attention-based readout on top of a frozen encoder to evaluate learned representations on downstream tasks. "We use attentive probing on downstream depth tasks unless otherwise mentioned."

- Camera pose: The position and orientation of the camera in 3D space, often used to relate multiple views. "our spatial pairing strategy uses camera poses and 3D point clouds (when available) to identify such image pairs."

- Correspondence Alignment Score (CAS): A training-free, patch-level metric that measures functional similarity between models via mutual top-k cross-attention correspondences. "Our Correspondence Alignment Score (denoted as CAS), visualised in Fig.~\ref{fig:CAS}, measures the similarity between two models , and is then defined as follows:"

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism where queries from one sequence attend to keys/values from another, enabling correspondence across views. "The cross-attention mechanism between , , and captures the pairwise similarity between target and source patch tokens"

- Cross-attention map: The matrix of attention weights produced by cross-attention, indicating how patches in one image attend to patches in another. "we construct a cross-attention map for each trained model, by aggregating the decoder attention map across all decoder blocks."

- Cross-view completion: A self-supervised objective that reconstructs masked regions in one view using information from another overlapping view to learn geometric correspondence. "we focus on geometric or structural downstream tasks, and thus adopt a proven self-supervised pipeline for learning geometry: cross-view completion"

- CroCo: A cross-view completion architecture using a Siamese encoder-decoder to learn geometry from overlapping image pairs. "We adopt the Cross-View Completion (CroCo) architecture~\citep{weinzaepfel2022croco}, a model recognized for learning robust geometric representations by observing scenes from multiple viewpoints."

- Delta-1 (δ1) accuracy: A depth metric denoting the fraction of pixels whose predicted-to-true depth ratio is below 1.25. "reporting the accuracy (the percentage of pixels with an error ratio below $1.25$)."

- DINOv2: A self-supervised vision model trained with a contrastive/distillation regime, often used as a strong baseline for representation learning. "we trained a DINOv2 model~\cite{oquab2023dinov2}, which uses a contrastive regime that combines single-image masking with distillation."

- Ego-motion estimation: Estimating the motion of the camera (observer) from visual input, common in egocentric and SLAM settings. "While some have used egocentric video for geometric tasks such as ego-motion estimation~\cite{krishna-wacv2016,zhou2017unsupervised,mai2023egoloc,EPICFields2023,engel2023projectarianewtool}"

- Egocentric video: First-person videos recorded from the viewpoint of an individual, capturing their visual experience. "we train a distinct vision model exclusively on egocentric videos captured by one individual."

- End-to-end training: Optimizing all model components jointly using a single objective. "The entire model is trained end-to-end by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the reconstructed and original pixels of the masked target patches"

- HPatches: A benchmark for local descriptors and correspondences with ground-truth optical flow under viewpoint/illumination changes. "we evaluate on the HPatches~\citep{balntas2017hpatches}, a benchmark of image pairs annotated with optical flow."

- Jaccard index: A set-overlap metric (intersection over union) used here to measure overlap of visible 3D points between frames. "measured by computing the Jaccard index between the visible 3D point clouds of two frames."

- Masked Autoencoder (MAE): A self-supervised method that reconstructs masked patches to learn visual representations. "which are adaptations of the Masked Autoencoder~\citep{he2022masked} to a Siamese architecture."

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): A loss function equal to the average of squared differences between predictions and targets. "by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the reconstructed and original pixels of the masked target patches"

- Monocular depth estimation: Predicting scene depth from a single RGB image. "Monocular Depth Estimation: Following common practice~\cite{weinzaepfel2022croco,carreira2024scaling}, we evaluate on two standard benchmarks."

- Multidimensional scaling (MDS): A technique to embed items in low-dimensional space while preserving pairwise similarities, used to visualize model alignment. "a 2D multidimensional scaling (MDS) projection~\cite{carroll1998multidimensional}"

- Mutual k-nearest neighbor: A symmetry-enhanced similarity notion where two sets agree on top-k neighbors, used to robustly compare representations. "we extend the robust mutual -nearest neighbor score introduced in \cite{huh2024platonic}, to a new metric, which evaluates how different models relate images on the patch level."

- MTopk (mutual top-k correspondence): The fraction of overlapping top-k correspondences between two attention maps for a given patch. "The mutual top correspondence measure denotes the fraction of mutual correspondences of , according to and :"

- Object permanence: The notion that objects persist even when not visible; used to emphasize shared physical structure in visual data. "Structural properties such as 3D Euclidean geometry and object permanence are universals that leave a consistent imprint on all visual data."

- Optical flow: A dense field describing apparent motion of pixels between frames, used for evaluating correspondence quality. "a benchmark of image pairs annotated with optical flow."

- Patch token: The tokenized representation of an image patch processed by a transformer. "captures the pairwise similarity between target and source patch tokens"

- Patch-Level Alignment Metric: A method to compare models at the granularity of image patches rather than whole-image embeddings. "Patch-Level Alignment Metric of Models"

- Platonic Representation Hypothesis: The idea that large models converge to a shared representation of reality when trained on diverse data. "the Platonic Representation Hypothesis~\cite{huh2024platonic}, which posits that large models trained on web-scale data converge towards a single representation of reality."

- Proprioception: The internal sense of body position used here as inspiration for pairing views with spatial overlap across time. "Our second signal is inspired by proprioception â a living being's innate sense of their body's position and orientation in space."

- Query–Key–Value (Q, K, V): The matrices used in attention mechanisms to compute weighted combinations of values based on query–key similarity. "form the query matrix , while the source features form the key and value matrices."

- ScanNet: A large-scale dataset of RGB-D indoor scans used for 3D reconstruction and depth evaluation. "ScanNet~\citep{dai2017scannet} is a large-scale 3D reconstruction dataset"

- Self-supervised learning: Learning representations from unlabeled data using pretext tasks or intrinsic signals. "to learn a visual encoder in a self-supervised manner."

- Shared World Hypothesis: The paper’s central claim that models trained on different individual lives converge to similar geometric representations due to shared physical reality. "we formulate the Shared World Hypothesis: because all lives are grounded in the same physical reality, geometric representations learned from these individual experiences should converge to a functionally similar structure."

- Siamese encoder–decoder transformer: A transformer architecture with shared-weight encoders for two inputs and a decoder that integrates them, used for cross-view reconstruction. "We use the same architecture as CroCo, a Siamese encoder-decoder transformer."

- Siamese MAE: A MAE variant with twin branches processing paired views to learn correspondence-aware features. "CroCo~\cite{weinzaepfel2022croco,weinzaepfel2023croco} and Siamese MAE~\cite{gupta2023siamesemae}, which are adaptations of the Masked Autoencoder~\cite{he2022masked} to a Siamese architecture."

- Spatial pairing: A view-pairing strategy that uses pose/3D overlap to select frames likely to depict the same scene from different viewpoints. "our spatial pairing strategy uses camera poses and 3D point clouds (when available) to identify such image pairs."

- Temporal pairing: A view-pairing strategy that leverages temporal proximity in videos to obtain overlapping views for correspondence learning. "We analyze models trained with temporal pairs, spatial pairs, and their union."

- Top-K: Selecting the k highest-scoring items (e.g., most attended patches) for ranking or matching. "we identify the top-K most attended-to patches in the target by both models, and compute their intersection."

- Vision Transformer (ViT): A transformer architecture that operates on image patches as tokens. "A weight-sharing ViT encoder, , processes the full set of source patches and the visible target patches "

- Zero-shot correspondence: Evaluating correspondence quality without task-specific fine-tuning, typically by directly using learned features or attention. " Zero-Shot Correspondence: To assess the robustness of our learned local descriptors under viewpoint and illumination changes, we evaluate on the HPatches~\citep{balntas2017hpatches}, a benchmark of image pairs annotated with optical flow."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a set of actionable use cases that can be deployed using the paper’s current findings and methods, with links to sectors, potential products/workflows, and feasibility notes.

- Personalized geometric encoders for AR calibration and spatial understanding

- Sector: AR/VR, mobile, software

- Application: Train a CroCo-style encoder from a user’s own short egocentric footage (30–60 minutes) to improve depth, pose, and correspondence in their home/office for more stable AR anchors and occlusion.

- Tools/Workflows: “Single-Life Trainer” pipeline using temporal pairing; attentive probing for downstream depth; on-device fine-tuning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Sufficient-quality egocentric video; device storage; basic GPU/NPUs on-device or in private cloud; privacy/consent workflow.

- Rapid home/office digital twin creation from personal videos

- Sector: Smart home, construction/real estate, facilities management

- Application: Auto-generate a 3D layout and depth map from a week of GoPro or smartphone videos for asset placement, renovation planning, and indoor navigation.

- Tools/Workflows: Temporal + spatial pairing (if poses available), CroCo pretraining; downstream depth estimation with attentive probing; ScanNet/NYU-like evaluation for QA.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Spatial pairing improves quality when camera poses are available; temporal pairing alone is effective; proper lighting and coverage.

- Privacy-preserving, per-user visual models for wearables

- Sector: Wearables, privacy tech

- Application: On-device single-life training for personalized geometry without aggregating multi-user data; reduces cross-user data transfer risks.

- Tools/Workflows: Edge training with temporal pairing; automatic data minimization (keep only learned weights); CAS-based periodic audits.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Sufficient compute on glasses/phone; battery constraints; regulatory compliance (consent, retention).

- CAS-based model alignment auditing and regression detection

- Sector: Software/ML ops, academia

- Application: Use CAS to monitor representational alignment between versions/models, detect drift, and verify functional similarity post-fine-tuning.

- Tools/Workflows: “CAS Audit Suite” integrating cross-attention extraction, MTopk computation, and dashboarding; test pair curation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to cross-attention maps; standardized test pairs; reproducible training.

- Robotics initialization from human egocentric walkthroughs

- Sector: Robotics (home service, logistics)

- Application: Let a robot bootstrap its scene geometry by training on the homeowner’s egocentric walkthrough videos before autonomous mapping; improves depth and correspondence priors.

- Tools/Workflows: Single-life CroCo pretraining on the homeowner’s video; deploy encoder for SLAM/VO front-end; zero-shot correspondence for feature matching (HPatches-like validation).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High overlap between human and robot viewpoints; domain shift management (indoor vs. outdoor).

- Insurance and claims documentation with geometric evidence

- Sector: Finance/insurance

- Application: Use personal egocentric video to produce depth-aware evidence of damages (e.g., water leak, fire) and room geometry for claims; faster adjuster review.

- Tools/Workflows: Single-life-trained encoders; downstream depth estimation; standardized export (meshes/point clouds).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Sufficient coverage of affected areas; admissibility standards; privacy of other household members.

- Personalized assistance for visually impaired navigation at home

- Sector: Healthcare, accessibility

- Application: Build a user-specific geometric model of home spaces from personal videos to enable precise audio/haptic guidance and obstacle alerts.

- Tools/Workflows: Temporal pairing for training; depth/correspondence pipelines; on-device inference; safety notifications.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Frequent updates for reconfiguration; ethical use and consent in shared spaces.

- Curriculum-aligned, spatially grounded training for task coaching

- Sector: Education, consumer apps

- Application: Use single-life geometry to anchor how-to AR overlays (e.g., cooking in the user’s kitchen) for step-by-step, environment-aware instruction.

- Tools/Workflows: CroCo encoder trained on the kitchen videos; alignment of overlays to observed surfaces; lightweight attention readout.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consistent spatial layout; handling of dynamic changes (moved utensils).

- Egocentric data collection best practices and pairing recipes for labs

- Sector: Academia

- Application: Adopt temporal pairing (and spatial pairing if poses are available) to train geometry-aware encoders from single-subject studies; use CAS to compare lives and curricula.

- Tools/Workflows: Pair-sampling library; CAS metric integration; shared test pairs; benchmark protocols (NYU/ScanNet/HPatches).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: IRB/ethics approvals; controlled data quality; reproducible sampling.

- Policy-aligned data minimization workflows

- Sector: Policy/regulatory, privacy

- Application: Codify single-life training and CAS-based auditing as privacy-preserving alternatives to multi-user aggregation; document the minimal data (≈1 hour) needed for usable alignment.

- Tools/Workflows: Data retention policies (weights retained, raw video discarded after training); CAS audits in compliance reports.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Legal validation in relevant jurisdictions; transparency to users.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, or productization beyond the paper’s current scope.

- Lifelong personal world models combining geometry and semantics

- Sector: Multimodal AI, AR assistants

- Application: A continuous, on-device model that learns a user’s spaces, routines, and objects, enabling richer task assistance (finding items, safety checks).

- Tools/Workflows: Extend single-life training beyond geometry (add semantics); continual learning; privacy-preserving memory.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust handling of drift and dynamic changes; efficient lifelong updates; consent and explainability.

- Federated “single-life” learning across many users without sharing raw video

- Sector: Privacy tech, cloud/edge AI

- Application: Aggregate model updates from many single-life models to improve global geometry priors while preserving privacy.

- Tools/Workflows: Federated averaging; CAS-based cross-model alignment monitoring; differential privacy; secure aggregation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Communication efficiency; privacy guarantees; heterogeneity of lives and devices.

- Standards for egocentric AI data collection, auditing, and deployment

- Sector: Policy/regulatory, industry consortia

- Application: Define norms for consent, retention, CAS-based audit requirements, and minimum data thresholds for safe deployment of personalized vision models.

- Tools/Workflows: Standardized CAS test sets; certification schemes; compliance toolkits.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder governance; international harmonization.

- Personalized robotics co-pilots leveraging “owner-world” priors

- Sector: Robotics

- Application: Robots that adapt their perception stacks to the owner’s environment via single-life priors, enabling safer navigation and task execution (cleaning, fetching).

- Tools/Workflows: Joint training pipelines (human egocentric + robot onboard sensors); dynamic re-alignment via CAS; task heads for manipulation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable transfer across viewpoints and embodiments; safety and liability frameworks.

- Enterprise facility mapping via operator bodycams

- Sector: Industrial operations, energy

- Application: Create 3D twins of plants and warehouses from single-operator runs; improve maintenance paths, safety inspections, and energy optimization.

- Tools/Workflows: Single-life training at scale; spatial pairing via IMUs/SLAM; integration with CMMS/BIM systems.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Hardware instrumentation; organizational buy-in; robust handling of large, complex spaces.

- CAS-driven model governance platforms

- Sector: ML ops, compliance

- Application: Enterprise tools that track alignment across many models and versions, flag anomalies, and enforce deployment gates based on CAS/other metrics.

- Tools/Workflows: Alignment dashboards; automated test pair generation; policy hooks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Standardized model interfaces; acceptance of CAS as a governance metric.

- Consumer memory augmentation and retrieval in personal spaces

- Sector: Consumer apps, accessibility

- Application: “Where did I leave X?” powered by single-life geometry and correspondence, enriched later with semantics; robust to rearrangements.

- Tools/Workflows: Continuous single-life updates; visual search heads; privacy-preserving indexing.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Long-term storage constraints; handling moving objects; user trust.

- Education and training in complex workspaces (labs, kitchens, workshops)

- Sector: Education, workforce development

- Application: Environment-aware coaching with personalized overlays and safety prompts grounded in each trainee’s single-life videos.

- Tools/Workflows: Mixed temporal/spatial pairing; curriculum design; continuous assessment.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Semantic grounding and hazard detection; institutional policies for recording; fairness and accessibility.

Notes on Assumptions and Dependencies

- Data: High-quality egocentric videos are required; minimal alignment emerges with ≈30–60 minutes, optimal gains from longer durations (~30 hours).

- Pairing strategies: Temporal pairing is universally available and effective; spatial pairing depends on camera pose/IMU or 3D reconstructions.

- Architecture: Findings generalize beyond CroCo (e.g., DINOv2), but task-dependent performance varies; geometry-centric tasks benefit most.

- Privacy: Strong consent and data minimization practices are essential; single-life training reduces cross-user aggregation risks.

- Generalization: Proven for geometry (depth, correspondence); semantic generalization remains a research area.

- Compute: On-device training/inference may be limited; hybrid edge/cloud strategies can mitigate.

- Environment dynamics: Models must handle rearrangements, lighting changes, and moving objects; periodic updates and CAS audits recommended.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.