- The paper presents CodeVision, a unified code-as-tool approach that dynamically composes operations for robust multimodal visual reasoning.

- It leverages multi-turn, multi-tool interactions and dense process rewards to enhance error recovery and strategic tool utilization.

- Experimental results show significant improvements in performance on vision benchmarks, demonstrating superior robustness over traditional MLLMs.

Current Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs) that "think with images" utilize explicit tool calls to perform operations such as cropping, zooming, and OCR as part of their reasoning chains. However, dominant paradigms display three critical weaknesses:

(1) Tool necessity is under-exercised—an overemphasis on cropping yields limited gains, and tools are seldom strictly required for success;

(2) Flexibility and scalability are hampered by hard-coded tool registries, rigid argument schemas, and poor generalization to unseen tools;

(3) Multi-turn, compositional tool reasoning remains shallow, rarely extending beyond single-turn, single-tool application.

Empirical analysis demonstrates a marked brittleness in state-of-the-art MLLMs: simply rotating or flipping input images severely degrades model performance, with accuracy dropping by up to 80%. Human performance is unaffected by such corruptions. This failure—quantified across multiple models—reveals an urgent need for robust, generalized, and compositional tool-use methodologies.

CodeVision directly addresses these challenges by reframing tool use: models are trained to generate programmatic code as a universal tool interface. This "code-as-tool" concept dissolves the constraints of fixed tool registries, allowing models to dynamically specify any operation, combining, parameterizing, and composing tools at will. The agent interacts with the environment by emitting code—for example, image manipulation routines—which is executed and the result (including errors or outputs) is fed back into the dialogue context.

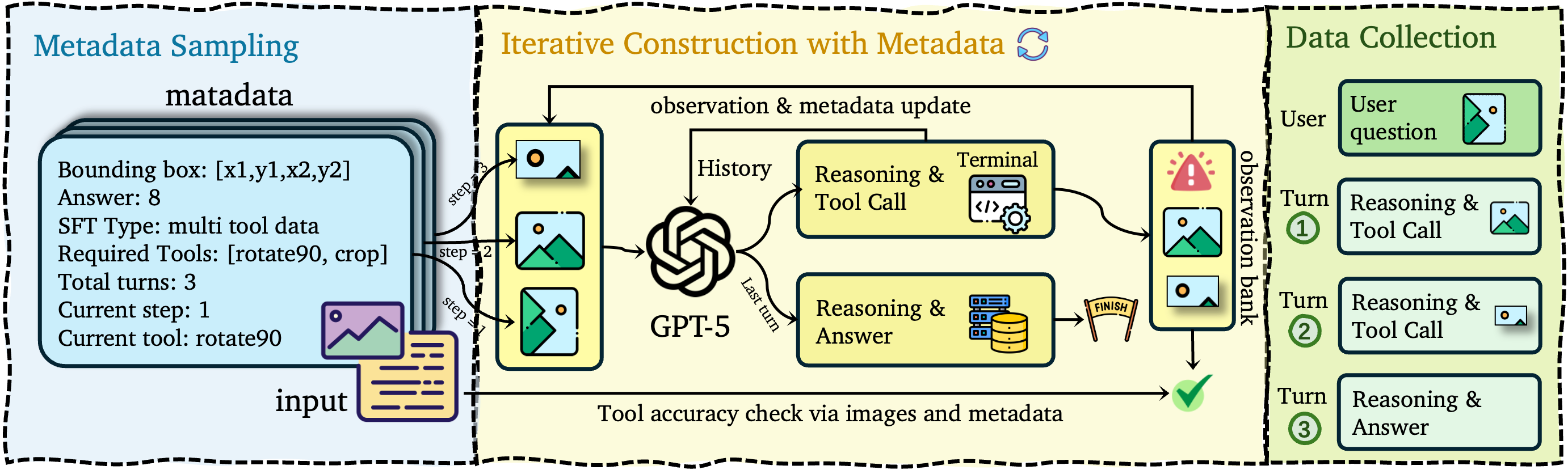

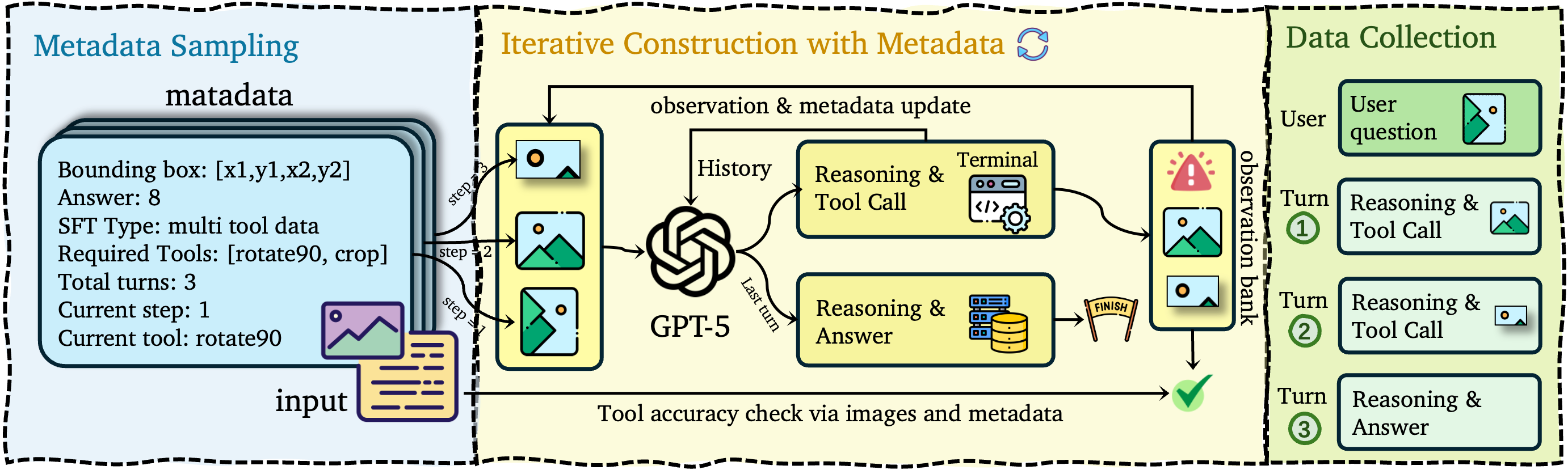

Figure 1: Pipeline for cold-start SFT data construction.

This flexible interface supports:

- Emergence of new tools: The model can invoke previously unseen operations.

- Compositional efficiency: Sequences of diverse operations are programmatically chained in a single turn.

- Robust error recovery: Runtime feedback (e.g., errors) enables dynamic code revision and correction.

Training Methodology: SFT, RL, and Dense Process Rewards

The CodeVision training protocol consists of two stages:

Supervised fine-tuning is performed on a curated corpus combining diverse vision tasks with explicit coverage of multi-tool, multi-turn, and error-handling trajectories. Each example is built via iterative metadata-driven sampling, automated tool execution/verification, and programmatic error injection. The resulting dataset covers (i) single-tool, (ii) multi-tool, (iii) multi-crop, (iv) error-handling, and (v) no-tool necessity.

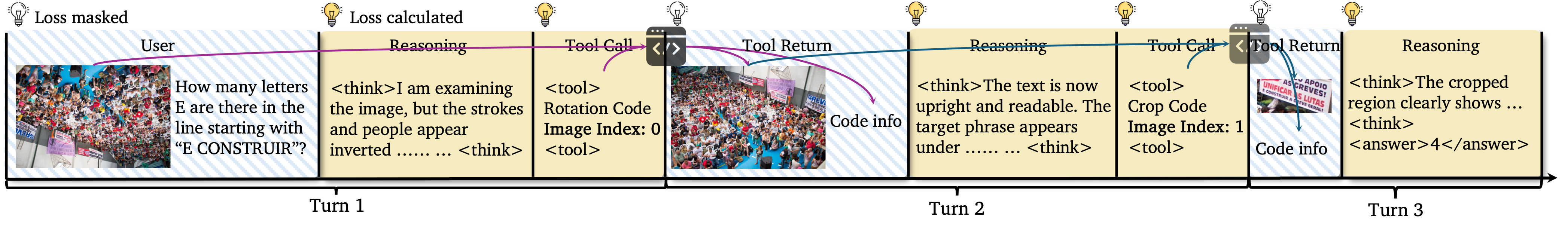

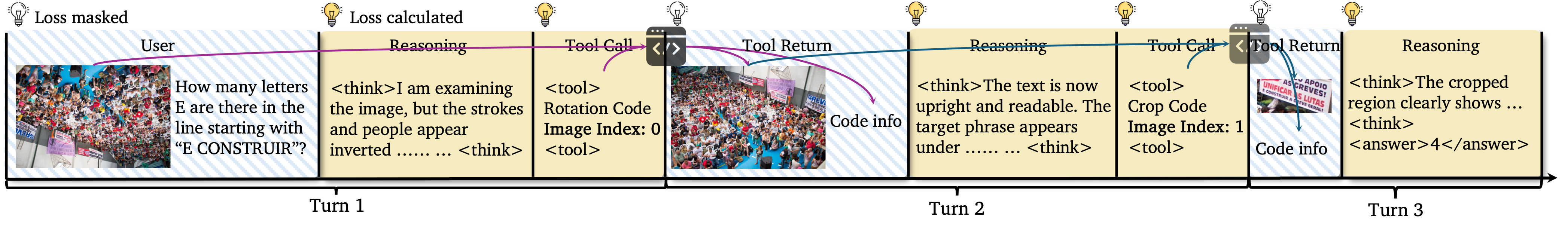

Figure 2: Rollout and inference process, and token masking used during SFT/RL.

Policy Optimization via RL with Dense, Multi-Component Rewards

Reinforcement learning is performed with a dense reward function designed to:

- Guide strategic tool use (must-use and suggested tools).

- Reward beneficial tool discovery (beyond strict necessity).

- Penalize reward hacking and inefficiencies.

Key reward components are:

- Outcome Reward: Terminal answer and formatting correctness.

- Strategy Shaping: Reward for required tools (with continuous improvement for crops via IoU) and empirical bonuses for optional but advantageous emergent tools.

- Constraint Penalties: Turn-limit, poor reasoning, and inappropriate tool-use penalties to suppress inefficient/hacky trajectories.

Comprehensive evaluation on a suite of robust vision-language benchmarks—spanning single-tool (V*, HRBench), multi-tool (MVToolBench), and orientation/transformation-heavy tasks (OCRBench, ChartQAPro with rotations/flips)—demonstrates substantially improved performance over both the base architecture and leading baselines.

- CodeVision-32B achieves 79.5 average accuracy on transformed OCRBench (+24 over Qwen2.5-VL-32B) and sets a new SOTA on the compositional MVToolBench with 65.4, more than double the score of the next-best model.

- Sample efficiency and stability throughout RL training are documented, with process rewards accelerating strategic policy discovery.

Figure 3: A multi-turn example of error recovery. The model initially calls the wrong tool (flip-horizontal), but after receiving the execution result, it identifies the mistake and corrects it by applying the right tool (rotate-90).

Qualitative analysis highlights:

- Multi-turn error recovery: The agent can recover from initial mistakes via runtime feedback.

- Emergent, efficient tool chaining: The agent spontaneously discovers and applies new compositions, sometimes combining tools unseen during RL.

- Failure suppression: Dense penalties effectively prevent "reward hacking" and superfluous tool invocation, focusing the model on deliberate, necessary actions.

Figure 4: An example of emergent and efficient tool use. The model chains two tools, contrast enhancement and grayscale conversion, within a single turn to fulfill the user's request. These tools did not appear in the RL training set, demonstrating the generalization capability of the code-as-tool framework.

Figure 5: An example of emergent and efficient tool use. The model chains ``brightness up, contrast up, crop, rotate90, sharpness'' tools to solve the user's request.

Figure 6: An example of reward hacking from a model trained without constraint penalties. After correctly applying rotate90, the agent continues to call superfluous tools, leading to task failure.

The case studies surface minor residual limitations, specifically in ultra-precise bounding box localization and occasional inefficiencies, delineating clear directions for further process supervision refinement.

Implications and Future Directions

The "code-as-tool" approach demonstrates that large vision-language agents can be robustified against real-world corruptions, efficiently generalize to new toolsets, and develop sophisticated, deliberate reasoning strategies. Practically, this paradigm removes bottlenecks in tool integration—static APIs, retraining barriers, and limited tool expressiveness—by leveraging the full expressive power of code. This enables agents to harness arbitrary external libraries, APIs, or black-box routines with minimal human intervention.

Theoretically, dense process shaping rewards, combined with code-based action spaces, point to a rich intersection of program synthesis and multimodal RL. Scaling up both the diversity of tools and the richness of supervision holds substantial promise for the emergence of increasingly capable and general multimodal reasoning agents.

Conclusion

CodeVision exposes fundamental brittleness in conventional MLLMs under realistic perturbations and demonstrates that programmatic, code-based tool usage—coupled with rigorous dense reward optimization—enables robust, efficient, and general visual reasoning. Empirical results and qualitative analyses substantiate the emergence of adaptive, compositional, and error-tolerant capabilities, suggesting that viewing image interaction as a programming task can become foundational in next-generation MLLMs. Future research should focus on further expanding tool diversity, refining reward shaping for nuanced tool selection, and exploring broader contexts such as multi-image and online tool integration.